Complex Congenital Heart Disease

I.TETRALOGY OF FALLOT (TOF). TOF is the most common form of cyanotic heart disease. It occurs in approximately 1 in 3,000 live births and accounts for 10% of congenital heart disease in infants. It is also the most common congenital heart disease condition requiring surgical correction in the first year of life. The earliest description of TOF dates back to the 17th century; however, Fallot is credited with describing the classic features of the disease in 1888. Surgical treatment for TOF did not become available until well into the 20th century, and it dramatically improved life expectancy. The current reparative approach has shifted from palliative shunt procedures to primary surgical repair, most recently with valve-sparing techniques and usually performed in infancy. Without surgical intervention, only about 10% of patients survive beyond the age of 20 years. Adults with TOF usually have undergone surgical repair or palliation. A wide and complex spectrum of TOF exists, including association with pulmonary atresia, absent pulmonary valve, and atrioventricular (AV) canal defects. Classic “simple” TOF is discussed here.

A.Anatomy

1.Anterocephalad deviation of the outlet septum results in four defining features:

a.Right ventricular (RV) outflow tract obstruction

b.Nonrestrictive ventricular septal defect (VSD)

c.Aortic override of the ventricular septum (>50% over the right ventricle)

d.Right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH)

2.Associated defects. Anomalous origin of the left anterior descending coronary artery from the right coronary artery (5%) or a prominent conal branch from the right coronary artery can occur. These vessels cross the RV outflow tract. This anatomic feature is important to surgeons because infundibular resection or future conduit placement may be needed in this location and can lead to inadvertent arterial damage. Right aortic arch occurs in 25% of cases. A secundum atrial septal defect (ASD) occurs in 15% of cases, completing the pentalogy of Fallot. Persistent left superior vena cava is found in 5% of patients. Among adult patients, aortic insufficiency can occur naturally from long-term dilation of the aortic root, after endocarditis or as a postoperative sequela. Rare complications include pulmonary hypertension, supravalvular mitral stenosis, and subaortic stenosis. There is an association with deletion in the chromosome 22q11 region, which is also present in DiGeorge syndrome and/or velocardiofacial syndrome.

B.Clinical presentation

1.Patients who have not undergone surgical repair have variable clinical features, depending on the amount of RV outflow tract obstruction, degree of aortic override, and, to a lesser extent, systemic vascular resistance, all of which dictate the amount and direction of shunting across the VSD.

a.With severe RV outflow tract obstruction, patients have central cyanosis and clubbing by 6 months of age. Hypoxic “spells” may be seen and are characterized by tachypnea, dyspnea, cyanosis, or even loss of consciousness or death. If the obstruction is mild, however, the shunt through the VSD may be left-to-right, resulting in “pink tet” with minimal symptoms.

2.Most adult congenital patients will have undergone surgical repair with or without a prior palliative procedure. The term “palliation” (as opposed to “repair”) in these patients refers to a surgical procedure that consists of a systemic-to-pulmonary artery shunt (modified Blalock–Taussig shunt, classic Blalock–Taussig shunt, Potts shunt, or Waterston shunt; Table 31.1). These procedures are initially performed to supplement the deficiency of antegrade pulmonary blood flow and are taken down at the time of complete repair. The latter two procedures have been abandoned because of associated uncontrolled pulmonary blood flow and the subsequent development of pulmonary hypertension.

TABLE 31.1 Index of Postoperative Anatomy among Adult Patients with Congenital Heart Disease |

||

Underlying Pathology |

Procedure |

Notes |

Single ventricle Hypoplastic left heart Tricuspid atresia |

1. Norwood |

Incorporation of native aorta and pulmonary artery (one of which may be hypoplastic or atretic) to produce a “neo-aorta” for the single ventricle |

Pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum Unbalanced complete AV canal defect |

Main pulmonary artery is transected from the heart Pulmonary flow is maintained with placement of a Blalock–Taussig shunt Atrial septectomy is often performed to allow complete mixing at the atrial level |

|

2. Bidirectional Glenn |

Usually performed at 4–6 mo if pulmonary arterial anatomy, pressures, and resistances are adequate Anastomosis of the superior vena cava to the pulmonary artery, usually with takedown of a previously placed systemic-to-pulmonary artery shunt and repair of pulmonary arterial branch stenosis if necessary Term bidirectional is used in descriptions of this procedure because both right and left pulmonary arteries usually remain in continuity |

|

3. Fontan |

Usually performed at 1–5 y depending on growth of vasculature and cyanosis Anastomosis of inferior vena cava to the pulmonary artery by intra-atrial lateral tunnel or extracardiac conduit Pulmonary blood flow is achieved passively, without the assistance of a ventricular pumping chamber |

|

dTGA (ventriculoarterial discordance) |

Rashkind |

Atrial balloon septostomy to create mixing of systemic and pulmonary circulation |

Blalock–Hanlon |

Surgical atrial septectomy |

|

Mustard or Senning (atrial switch) |

Baffle material (Mustard) or native atrial tissue (Senning) used to direct pulmonary venous blood → right ventricle → aorta; systemic venous blood → left ventricle → pulmonary artery |

|

Jatene (arterial switch) |

Great arteries are transected and reanastomosed to the appropriate ventricle Coronary arteries are removed with a button of surrounding tissue and reimplanted to the appropriate sinuses |

|

Rastelli |

For dTGA with VSD and pulmonary outflow tract obstruction VSD patch closure that directs left ventricular blood across the VSD to the aorta Pulmonary valve is oversewn Valved conduit from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery to create RV outflow |

|

Deficient pulmonary artery or RV outflow tract Pulmonary atresia, tetralogy of Fallot with hypoplastic pulmonary arteries |

Classic Blalock–Taussig Modified Blalock–Taussig Waterston shunt Potts shunt |

Native subclavian artery anastomosed to the right or left pulmonary artery Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex) material connecting the subclavian or innominate artery to the pulmonary artery Anastomosis between the ascending aorta and right pulmonary artery Anastomosis between the descending aorta and left pulmonary artery |

AV, atrioventricular; RV, right ventricular; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

a.Patients who have undergone palliative repair alone have variable clinical findings, depending on the type of palliation performed. In those who have undergone a classic Blalock–Taussig shunt, the brachial pulse on that side may be diminished or absent. If patent, shunts can produce a continuous murmur. Continuous murmurs can also result from aortopulmonary collaterals. Branch pulmonary artery stenosis at prior shunt insertion sites can produce unilateral systolic or continuous murmurs. Systolic ejection murmurs may be audible depending on the degree of antegrade flow across the outflow tract.

3.Complete (or total) repair consists of patch closure of the VSD and variable degrees of RV outflow tract resection and reconstruction. It may involve pulmonary valvotomy, RV outflow tract patch augmentation, transannular patch enlargement, or placement of a right ventricle–to–pulmonary artery conduit (i.e., bioprosthetic or homograft). Distal branch pulmonary artery stenosis may have been repaired, or residual lesions may be present. These patients typically have first undergone a palliative shunt procedure, but the current surgical approach has shifted to primary complete repair in infancy.

a.Patients are often asymptomatic. They may present with late symptoms such as dyspnea, exercise intolerance, palpitations, signs of right heart failure, or syncope.

b.The jugular venous pressure is usually normal unless there is RV dysfunction, in which case elevated jugular venous pressure with a prominent a wave is seen. The brisk pulse of aortic insufficiency may also be appreciated. On palpation, there may be an RV lift or a lift under the right sternoclavicular junction when the arch is right sided. Some degree of turbulence almost always remains across the RV outflow tract and produces a variable systolic ejection murmur at the left upper sternal border, with radiation to the back and peripheral lung fields. Of importance is the presence of associated pulmonary insufficiency. This, even if severe, may occasionally be inaudible due to low-pressure hemodynamics. It is generally appreciated at the left upper sternal border, sometimes producing a to-and-fro murmur together with the outflow tract murmur. A high-frequency systolic murmur at the left lower sternal border suggests the presence of a residual VSD (often due to a small leak in the VSD patch). Continuous murmurs from collateral formation or prior shunts may be appreciated. The diastolic murmur of aortic insufficiency may also be heard.

C.Laboratory examination

1.Chest radiographic findings depend on the surgical history. The presence of a right aortic arch may be confirmed. A concave deficiency of the left heart border reflects various degrees of pulmonary arterial hypoplasia. Upturning of the apex from RVH causes the classic finding of a “boot-shaped” heart. Pulmonary vascular markings may vary throughout the lung fields, depending on associated branch pulmonary artery stenosis and relative blood flow. Calcification or aneurysmal dilation of surgical conduits or RV outflow tract repair may be visible on plain radiographs.

D.Diagnostic testing

1.Echocardiography

a.For a child or young adult, transthoracic echocardiography may be the only modality necessary for diagnosis. For adults or patients who have undergone surgical intervention, catheterization or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be necessary in order to identify the presence and location of residual lesions.

(1)It is clinically useful to identify a residual VSD or the presence of aortic insufficiency. Palliative shunts are often best visualized in the suprasternal notch view, where the subclavian arteries course distally.

(2)Continuous flow is typically demonstrated with color Doppler techniques. Less common shunts may be difficult to image in adult patients. Aortopulmonary collateral vessels are extremely difficult to visualize but may be seen in suprasternal notch views of the descending aorta.

b.Transesophageal echocardiography may allow improved imaging of the intracardiac anatomic structures in adults, but limitations often remain with regard to the distal pulmonary arteries, and additional testing is frequently necessary.

2.Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is considered the gold standard for evaluating the right ventricle and quantitating pulmonary insufficiency in these patients. It can demonstrate the presence of scar, distal pulmonary arterial anatomy, and RV aneurysms, as well as other associated defects. It can also provide hemodynamic information about residual lesions. Previously placed shunts and possibly aortopulmonary collateral vessels can be identified as well. The anatomic information may be sufficient to proceed with surgical treatment or to guide the interventional cardiologist in planning a transcatheter procedure.

3.Cardiopulmonary testing should be performed as a baseline study and with progression of symptoms. It is useful in determining the timing for reintervention in the setting of RV volume overload secondary to free pulmonary insufficiency.

4.Quantitative pulmonary flow scans are useful to determine discrepancies in pulmonary flow that may be caused by branch pulmonary artery stenosis. These scans also provide objective baseline clinical information when obtained after surgical or transcatheter intervention.

5.The role of cardiac catheterization is decreasing with the advent of other imaging modalities but can be helpful in assessing residual shunts, branch pulmonary stenosis, and pulmonary hypertension.

a.Right heart catheterization. Residual shunts are actively sought at the atrial and ventricular levels. The pulmonary arteries and branches are evaluated extensively in search of peripheral pulmonary stenosis. Findings at right heart catheterization and their clinical significance are as follows:

(1)RV pressure is generally systemic in a patient who has not undergone surgical repair.

(2)After surgical repair, elevated RV pressure suggests the presence of residual obstructive lesions, the levels of which are to be documented.

(3)Careful pullback recordings are performed from the branch pulmonary arteries to the right ventricle because stenosis at each level is possible.

(4)The presence of stenosis at a prior shunt site is expected.

(5)RV end-diastolic pressures may be elevated in the setting of pulmonary insufficiency.

b.Left heart catheterization is performed if noninvasive studies suggest residual VSD.

(1)Angiography includes a cranialized right ventriculography and possibly selective pulmonary arterial injections if hemodynamic findings suggest stenosis.

(2)Left ventriculography better demonstrates residual VSD in the presence of subsystemic RV pressures.

(3)Aortic root injection demonstrates the presence of aortic insufficiency, confirms the presence of grossly abnormal coronary artery origins or branching patterns, and reveals prior surgical shunts or aortopulmonary collateral vessels. If present, shunts and collateral vessels are best visualized in the posteroanterior and lateral projections after selective injection by hand.

(4)Selective coronary angiography is recommended in the care of adult patients to exclude acquired coronary artery disease and to identify the path of any anomalous coronaries before surgical intervention. The anomaly that is not to be missed is the left anterior descending artery originating from the right coronary artery—it crosses the RV outflow tract anteriorly and can be damaged during surgery.

E.Therapy and follow-up care

1.Medical treatment

a.If an adult has not been surgically treated or has undergone palliative treatment, a relatively well-balanced situation must exist. However, the following problems are to be expected.

(1)Long-term effects of RV outflow obstruction

(2)Progressive infundibular pulmonary stenosis

(3)Exposure of the pulmonary circulation to systemic shunt flow

(4)Development of distal pulmonary arterial stenosis, typically at shunt sites

(5)Erythrocytosis

(6)Chronic hypoxemia

(7)Pulmonary hypertension

(8)Paradoxical emboli

(9)Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias

(10)Increased risk of aortic insufficiency over time

(11)Endocarditis

b.Follow-up care increasingly involves patients who have undergone surgical repair and management of residual postoperative lesions.

(1)These patients are at increased risk for sudden cardiac death. Atrial and ventricular rhythm disturbances are common in the postoperative patient. Frequent Holter monitoring is warranted for this reason. Atrial tachyarrhythmias are found in up to one-third of patients and are predictive of morbidity and mortality. If patients are found to have nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, an electrophysiologic study and possibly an implantable cardioverter–defibrillator implantation can be considered. Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias may be the presenting problem for postrepair patients when a component of the repair is failing. There are no data to support prophylactic antiarrhythmic therapy to lower risk of sudden death in this patient population. An increased incidence of ventricular rhythm abnormalities has been associated with RV volume overload from pulmonary insufficiency and with QRS prolongation >180 ms (QRS duration correlates with degree of RV dilation).

(2)Pulmonary insufficiency can be tolerated for years, even decades, but chronic volume loading of the right ventricle can lead to diminished exercise tolerance, dysrhythmias, and right heart failure. Pulmonary insufficiency is the most common indication for redo surgery after an initial repair.

(3)Residual VSD

(4)Progressive dilation of the ascending aorta

(5)Residual RV outflow tract gradient

(6)RV outflow tract aneurysm at previous patch site

c.Recent infective endocarditis guidelines have departed considerably from prior iterations in that antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended only for those who are at highest risk for adverse outcomes from endocarditis. Specifically, prophylaxis is still appropriate for patients with TOF who are unrepaired, including those who have undergone a palliative procedure. For patients with TOF who have undergone total repair, antibiotic prophylaxis is now recommended only for 6 months following the placement of prosthetic material or device or if there is a residual defect at, or adjacent to, the site of prosthetic material (VSD patch leak, for example). If the pulmonary valve has been replaced or repaired with prosthetic material, antibiotic prophylaxis is appropriate as well.

2.The primary therapeutic consideration for patients with TOF is surgical intervention—either repair or reintervention.

a.The goal of total repair is to relieve the outflow tract obstruction while maintaining the competency of a preferably native pulmonary valve with closure of the VSD. Some younger patients need extensive reconstruction of the RV outflow tract with early placement of a bioprosthetic valved conduit or homograft. In time, these usually become restrictive to flow and/or are insufficient. The result is progressive right heart hypertrophy, fibrosis, and failure if revision is not performed.

b.A common indication for reintervention is pulmonary valve replacement (PVR) for severe pulmonary valve insufficiency. The ideal timing for PVR, however, remains controversial. Cardiac MRI may be helpful in determining optimal timing, and there is evidence to support pursuing pulmonic valve replacement before the RV end-diastolic volume index reaches 160 mL/m2.

c.Other indications for reintervention include the replacement or revision of conduits/homografts in the presence of symptoms, residual VSD with reasonable shunt (approximately 1.5:1), RV pressures greater than two-thirds of systemic pressures because of residual obstructive lesions, progressive aneurysmal dilation of RV outflow tract patch, residual systemic–pulmonary shunts with left ventricular volume overload, clinically significant arrhythmias, symptomatic or progressive aortic insufficiency, and significant progressive aortopathy (>5.0 cm).

3.Although the mainstay of therapy has been surgical, transcatheter techniques are increasingly used to treat patients in certain situations. For the most part, transcatheter therapies for adults with TOF are limited to patients who have undergone prior surgical treatment, with attention to residual obstructive lesions in the main pulmonary artery, right ventricle–to–pulmonary artery conduit, or distal pulmonary arteries. Prior shunt sites may become stenotic with time and necessitate balloon angioplasty and possibly stent placement. Residual VSD and ASD may be closed percutaneously in select situations. Percutaneous pulmonic valve replacement has been approved for use both in Europe and the United States. The Melody valve (Medtronic; Minneapolis, MN) is a therapeutic option available for selected patients with stenotic or regurgitant conduits.

II.COMPLETE TRANSPOSITION OF THE GREAT ARTERIES (dTGA). This is a relatively common congenital anomaly that occurs with a prevalence of 20 to 30 in 100,000 live births and is found more often in males (2:1). It is not associated with other syndromes and does not tend to cluster in families. Although it represents 5% to 8% of all congenital heart disease, it accounts for 25% of deaths in the first year of life. Adult patients almost invariably have undergone prior surgery and carry with them important morbidities that require ongoing surveillance and care.

A.Anatomy

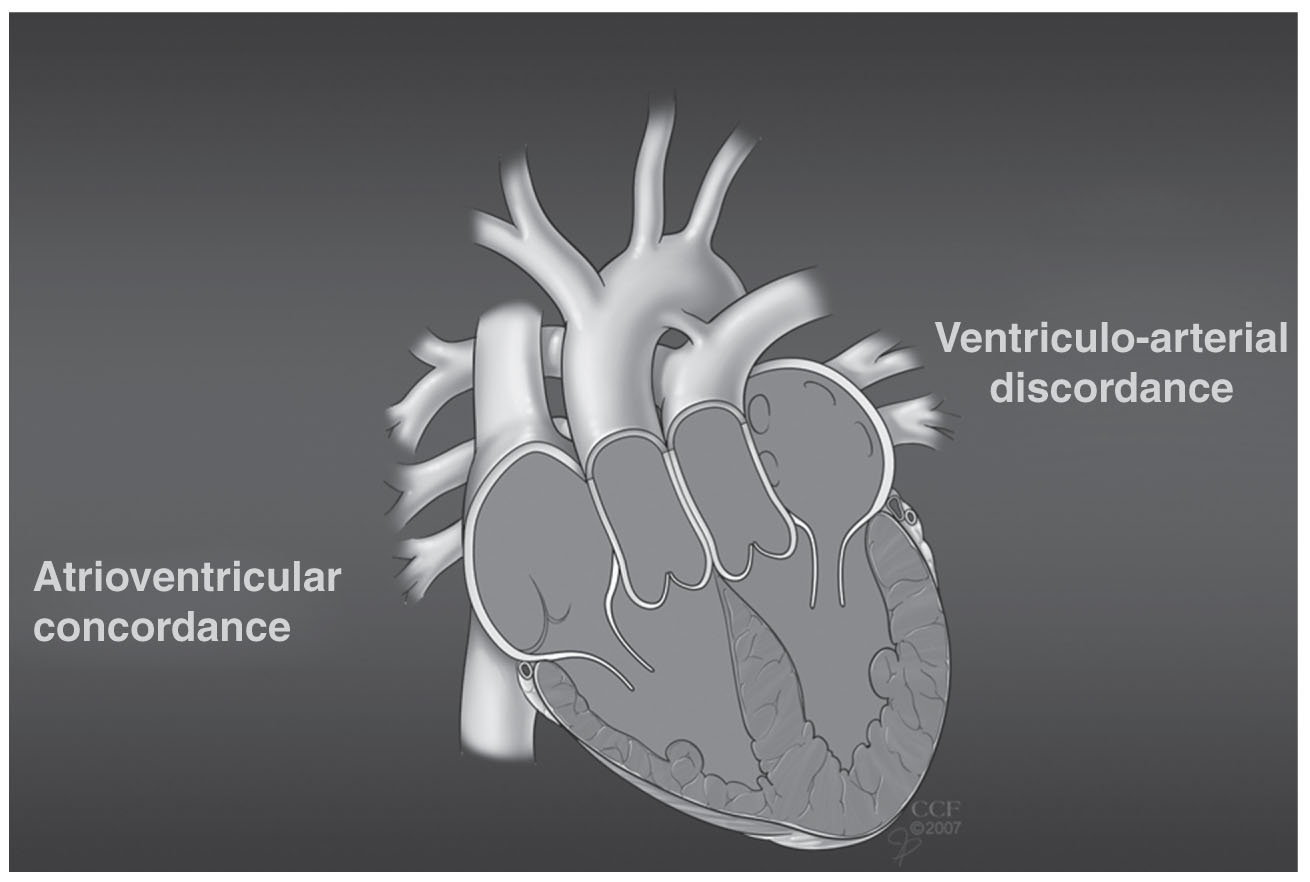

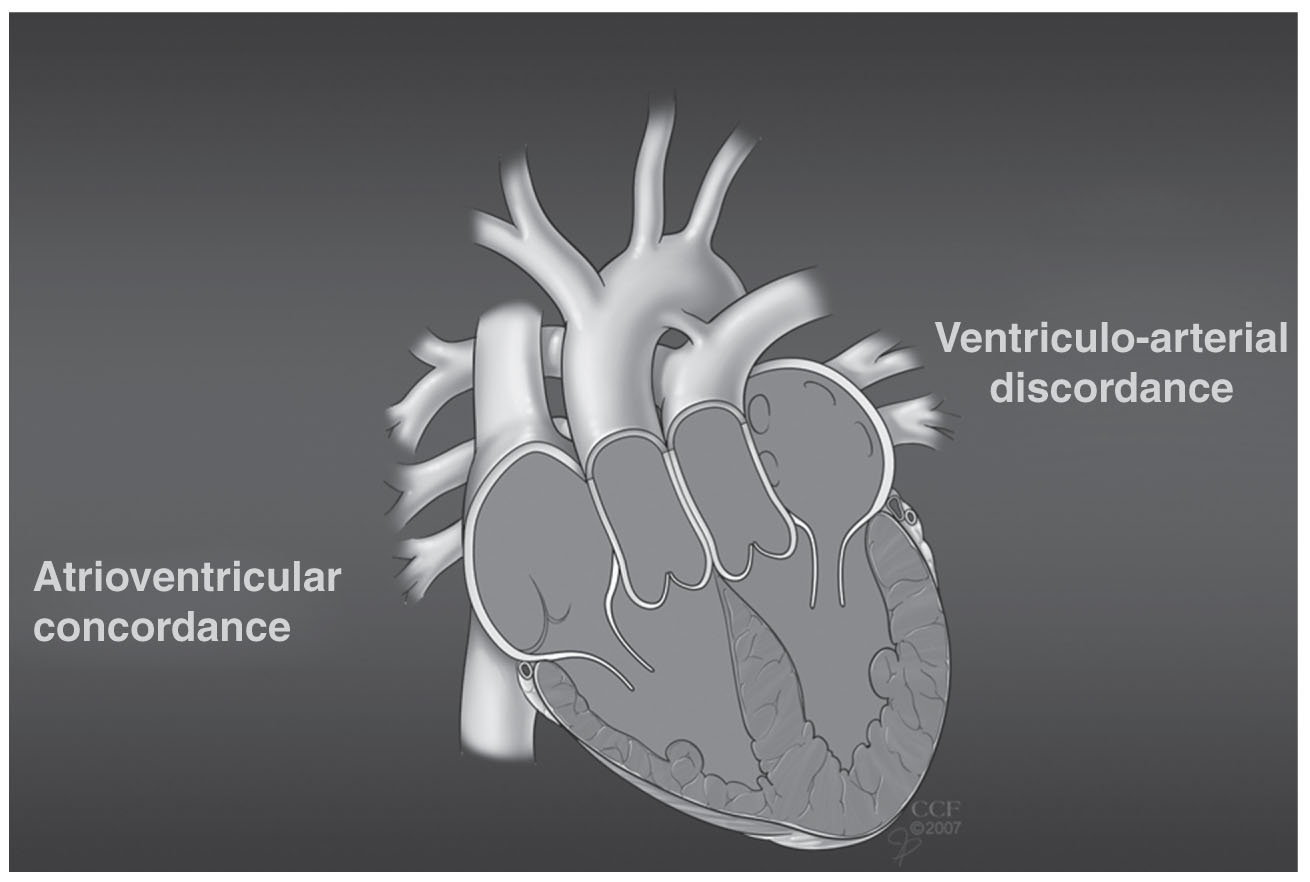

1.The defining feature of this anomaly is ventriculoarterial discordance, in which there is an abnormal alignment between the ventricles and the great arteries. Hence, the aorta arises from the right ventricle, and the pulmonary artery arises from the left ventricle, creating two parallel circuits instead of one in series. Deoxygenated blood flows from the right atrium across a tricuspid valve → right ventricle → aorta, whereas oxygenated blood flows from the left atrium across the mitral valve → left ventricle → pulmonary artery. Unless there is bidirectional shunting at the atrial (ASD), ventricular (VSD), or great artery level (patent ductus arteriosus) to allow mixing of blood, this anatomy is incompatible with life (Fig. 31.1).

FIGURE 31.1 Complete (d) transposition of the great arteries.

2.There is an abnormal spatial relationship between the great arteries such that instead of the normal spiral configuration, they run parallel to one another. The aorta is rightward and anteriorly displaced, whereas the pulmonary artery occupies a position more leftward and posterior. This is the most common pattern, but other configurations can also be seen, such as side-by-side great arteries with the aorta to the right or an aorta directly anterior to the pulmonary artery.

3.Associated cardiac anomalies include VSD in 40% to 45% of cases (usually perimembranous but can involve any portion of the interventricular septum), left ventricular (or subpulmonary) outflow tract obstruction in 25%, aortic coarctation in 5%, patent foramen ovale (PFO), and patent ductus arteriosus. Patients with these associated cardiac anomalies are considered to have complex transposition, whereas patients without these associated anomalies are considered to have simple transposition.

4.This lesion is also referred to as “dTGA,” in which the “d” refers to the dextroposition of the bulboventricular loop, which is characterized by a right-sided right ventricle.

5.The coronary anatomy in dTGA is variable. The aortic sinuses are described according to their relationship to the pulmonary artery, such that the “facing sinuses” are closest to the pulmonary artery. The most frequent coronary arrangement is when the “left-facing” sinus gives rise to the left main coronary artery, whereas the “right-facing” sinus gives rise to the right coronary artery.

B.Natural history and surgical repair

1.Without surgical intervention, survival beyond infancy is dismal, with 89% mortality by the first year of life and worse outcomes for those without an associated lesion to allow for adequate mixing of blood. At birth, infants are treated with intravenous prostaglandin E to keep the ductus arteriosus open, and some may undergo a Rashkind procedure (Table 31.1) to improve oxygenation until definitive surgery can be performed.

2.Adults invariably have undergone some type of cardiac surgery, although in rare cases they may present with Eisenmenger physiology (see subsequent text) if a “balanced” situation exists with a concomitant large VSD and pulmonary vascular disease. Surgical repairs include the atrial switch procedure (Senning or Mustard operation), the arterial switch procedure (Fig. 31.2), or the Rastelli operation (Table 31.1).

FIGURE 31.2 Arterial switch operation.

C.Clinical presentation

1.The clinical presentation of the surgically repaired patient with dTGA depends on the type of previous surgery. Although no longer cyanotic, these patients have a host of mid- to late-term morbidities that require lifelong surveillance. Patients who have undergone an arterial switch procedure are approaching adulthood only now and presenting in adult congenital cardiology clinics.

2.Atrial switch (Mustard or Senning)

a.Patients who have undergone an atrial switch operation often report New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class I–II symptoms but on exercise testing may have significant exercise intolerance. They have a systemic right ventricle, which, over time, can develop systolic dysfunction and progressive tricuspid regurgitation. These patients may present with signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure—the most common cause of death. Arrhythmias are common, and patients may present with palpitations, presyncope, or syncope. Venous baffle obstruction can lead to peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, ascites, and fatigue because of low cardiac output. The obstruction of the superior limb can produce a superior vena cava syndrome. Pulmonary venous baffle obstruction can lead to fatigue, exertional dyspnea, and chronic cough. Baffle leaks are often asymptomatic, but large leaks can lead to intracardiac shunting and cyanosis.

b.On physical examination, focus should be on signs of AV regurgitation and heart failure. There may be an RV heave at the left sternal border on palpation. S2 is loud at the second left intercostal space from an anterior aorta. Audible splitting of the S2 may indicate the development of pulmonary hypertension.

3.Arterial switch

a.This has become the standard corrective surgery for those born without significant left ventricular outflow obstruction. The majority of these patients are asymptomatic with NYHA functional class I symptoms. Arrhythmias are not a significant problem with this subset. Few will present with chest pain, and in these patients ischemia must be ruled out.

b.The physical examination is sometimes notable for turbulence across the RV outflow tract, which may be palpated as a thrill. The diastolic murmur of aortic insufficiency should also be sought.

4.Rastelli operation

a.Both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias are mid- to late-term complications, and patients with these conditions may present with palpitations or syncope. Conduit obstruction may manifest as insidious exercise intolerance, dyspnea, or new-onset arrhythmias. On physical examination, the character of the pulmonic ejection murmur should be carefully noted to evaluate for conduit obstruction.

D.Laboratory examination

1.The chest radiograph of patients with dTGA displays a narrow mediastinum because of the parallel orientation of the great arteries. The cardiothoracic silhouette is normal. The pulmonary vasculature is normal in patients without pulmonary hypertension. The right ventricle–to–pulmonary artery conduit in patients who have undergone a Rastelli procedure may be visualized on plain radiograph because of calcification.

2.In patients who have undergone an atrial switch operation, the electrocardiogram may display an ectopic atrial or junctional rhythm because of loss of sinus node function. There is usually right-axis deviation and RVH as a result of the systemic position of the right ventricle. In patients who have undergone arterial switch, RVH is distinctly abnormal and suggests pulmonary outflow tract obstruction. After a Rastelli operation, the electrocardiogram is notable for a right bundle branch block, and patients may develop complete heart block.

E.Diagnostic testing

1.Transthoracic echocardiography in atrial switch patients can assess the degree of tricuspid regurgitation and estimate RV function. Color Doppler is helpful in detecting baffle leaks or obstruction, although more detailed analysis may require transesophageal echocardiography. For those who have undergone arterial switch, transthoracic echocardiography can assess left ventricular function and help exclude supravalvular and pulmonary artery stenosis. Two-dimensional Doppler can be used to look for conduit stenosis after the Rastelli operation and estimate RV systolic pressures. It can also exclude any residual VSDs in these patients.

2.As in the TOF population, CMR imaging has emerged as an invaluable imaging modality for patients with repaired dTGA. For post–atrial switch patients, CMR imaging is used to quantify the size and function of the right ventricle, assess tricuspid regurgitation, and evaluate the systemic and pulmonary venous limbs of the atrial baffle for potential obstruction or leaks. In patients who have undergone arterial repair, right and left ventricular function can be quantitated and both the right and left outflow tracts examined. Focus is placed on the great arteries to look for the presence of supravalvular and branch pulmonary artery stenosis as well as dilation of the neo-aorta. Conduit stenosis and gradients as well as RV size and function can be determined in those who have had a Rastelli operation.

3.Cardiopulmonary testing is very useful in detecting subtle clinical changes and decrease in functional capacity. As mentioned previously, there is often a discrepancy between self-reported symptoms and performance on metabolic exercise testing. Patients who have undergone atrial switch often have chronotropic incompetence and may benefit from pacemaker implantation. Stress testing may be useful in patients after arterial switch to detect coronary artery stenosis and resultant ischemia.

4.Quantitative pulmonary flow scans are an important part of the diagnostic workup for suspected pulmonary artery or branch pulmonary artery stenosis in those who have undergone arterial switch repair. It is useful to obtain these scans before and after potential intervention to assess for functional improvement.

5.Cardiac catheterization does not have a role in the routine management of these adult patients. It does have a role, however, in the diagnosis and treatment of baffle obstruction and leaks, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary artery stenosis, coronary artery stenosis, conduit obstruction, and residual VSD.

F.Therapy and follow-up

1.Follow-up should focus on potential late complications after repair and depends on the type of surgery the patient has undergone.

a.Atrial switch

(1)Arrhythmias including sinus node dysfunction and intra-atrial reentry tachycardia (frequent Holter monitoring is recommended)

(2)RV dysfunction

(3)Tricuspid regurgitation

(4)Sudden cardiac death

(5)Baffle obstruction or leak

(6)Pulmonary hypertension

(7)Endocarditis

b.Arterial switch

(1)Supravalvular or peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis

(2)Pulmonary outflow tract obstruction

(3)Neo-aortic regurgitation and aortic root dilation

(4)Coronary artery stenosis leading to ischemia and sudden death

(5)Left ventricular dysfunction

(6)Endocarditis

c.Rastelli operation

(1)Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias

(2)Complete heart block

(3)Sudden cardiac death

(4)Left ventricular dysfunction

(5)Conduit stenosis

(6)Endocarditis

2.Medical management

a.In the treatment of systemic RV dysfunction, there are limited data to suggest any long-term benefits from applying the evidence-based drugs utilized for left ventricular dysfunction. Despite this, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are often utilized for afterload reduction. β-Blockers should be used with caution in patients after atrial switch repairs, because this could precipitate heart block (due to sinus node and AV conduction abnormalities).

b.As mentioned previously, the latest infective endocarditis guidelines have changed such that in the absence of valve replacement or prosthetic material used to repair a valve, implantation of prosthetic material within the last 6 months, or prosthetic material accompanied by residual leaks, it is no longer officially recommended that dTGA patients postrepair receive antibiotic prophylaxis.

3.Late intervention options include both surgical and transcatheter procedures and, again, depend on the type of repair. Systemic ventricular failure may ultimately require workup for orthotopic heart transplantation.

a.Atrial switch

(1)The procedure of choice in patients with baffle obstruction is transcatheter stent implantation, with best results in the systemic venous baffle. Although technically more challenging, transcatheter dilation of the pulmonary venous baffle can be performed but may require surgical revision. Clinically significant baffle leaks can be treated with catheter-based techniques as well as with septal occluder devices.

(2)In view of the high prevalence of atrial arrhythmias and sinus node dysfunction, these patients are referred for radiofrequency ablation procedures and pacemaker implantation.

(3)Conversion to an arterial switch for systemic RV dysfunction or left ventricular “training” by pulmonary artery banding has not been reliably successful in the adult population and has been largely supplanted by cardiac transplantation in many centers.

b.Arterial switch

(1)Percutaneous balloon angioplasty with or without stent placement is an excellent option for those with pulmonary artery and supravalvular or branch pulmonary artery stenosis with suitable anatomy. Balloon angioplasty being a safe procedure, there is an approximately 15% restenosis rate, with lower risk after stent implantation. The greatest success lies with branch pulmonary artery stenosis.

(2)Coronary artery stenosis can be treated with both stenting and coronary bypass surgery.

(3)Severe neo-aortic regurgitation is treated surgically with either valve repair or replacement.

c.Rastelli operation

(1)All right ventricle–to–pulmonary artery conduits inevitably fail and require replacement. There is a role for percutaneous stenting of conduit obstruction in some patients, because this can delay the need for surgery. These transcatheter procedures have a risk of stent fracture as well as potential for coronary artery compression, which can lead to catastrophic outcomes in the catheterization laboratory.

(2)Residual VSD leaks may be amenable to closure by percutaneous means but often require surgical revision. Clinically significant residual left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is also managed surgically.

III.CONGENITALLY CORRECTED TRANSPOSITION OF THE GREAT ARTERIES (ccTGA). Ventricular inversion or ccTGA is a rare congenital anomaly that occurs in <1% of children with congenital cardiovascular defects. Among these patients, it is equally rare to have no other associated structural abnormalities. The natural history of ccTGA is gradual congestive heart failure caused by systemic AV valve insufficiency and systemic ventricular dysfunction, even in the absence of other associated malformations. The presence of associated defects and conduction abnormalities contributes to a further decrease in life expectancy without intervention. Life expectancy is generally good but does not reach normal.

A.Anatomy

1.The defining feature of this congenital abnormality of cardiac looping is AV and ventriculoarterial discordance. Blood flows from the right atrium across a mitral valve → right-sided, morphologic left ventricle → pulmonary artery → lungs → left atrium across a tricuspid valve → left-sided, morphologic right ventricle → aorta (Fig. 31.3).

FIGURE 31.3 Congenitally corrected (l) transposition of the great arteries. Ao, aorta; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

2.The great arteries are not in their normal configuration and often run parallel to one another instead of crossing. The pulmonary artery is more posterior and rightward than usual, and the aorta is more anterior and leftward.

3.The anatomic coronary arteries, like the AV valves, follow their respective ventricles. The left-sided coronary artery resembles the anatomic right coronary artery as it courses in the AV groove and gives rise to infundibular and marginal branches. The right-sided coronary artery resembles the morphologic left coronary artery, which branches into the anterior descending and circumflex arteries (Fig. 31.4).

FIGURE 31.4 Schematic representation of coronary artery origins and branching in the normal heart (A) and in a congenitally corrected transposition (B).

4.The conduction system likewise follows the respective ventricle, as the right-sided, morphologic left ventricle depolarizes first. Accessory AV nodal tissue is located anteriorly with respect to normal, and the His bundle must traverse anterior to the pulmonary artery and along the superior margin of a VSD if present. There is increased risk of acquired complete heart block in this lesion because of the abnormally placed AV node and its extended course. Approximately 30% of adolescents and adults develop complete heart block, the incidence of which is 2% per year without surgical intervention, with the site of block being within or above the His bundle. Accessory pathways have been described and are typically left sided in the presence of an Ebstein anomaly–like malformation of the left-sided (tricuspid) AV valve.

5.Isolated ccTGA is the exception. Associated lesions are common and are considered in the diagnostic evaluation. They include VSD (70%), pulmonary outflow obstruction (~40% and usually subvalvular), or abnormalities of the left-sided, systemic tricuspid valve. Up to 90% of patients have an abnormality of the tricuspid valve in some form (i.e., dysplastic or Ebstein-like tricuspid valves).

B.Clinical presentation

1.Because physiologic blood flow is preserved, patients may have no symptoms through adulthood in the absence of other structural lesions or associated complications. This scenario is rare, however, because associated lesions commonly dictate the clinical features.

2.Without associated structural abnormalities, failure of the systemic morphologic right ventricle with various degrees of systemic AV valve (tricuspid) insufficiency is the norm. In this setting, the patient has nonspecific descriptions of fatigue, shortness of breath, and exercise intolerance or congestive failure. Patients may have syncope or presyncope caused by conduction abnormalities or complete heart block.

3.On physical examination, there is a loud A2 caused by an anterior and leftward aorta. The murmurs of a VSD or pulmonary stenosis may also be appreciated. Tricuspid insufficiency can be heard with systemic ventricular failure.

C.Laboratory examination

1.In the usual anatomic configuration of ccTGA, the aorta is anterior and to the left, which produces a chest radiograph with a straight left heart border. The left pulmonary artery is not well defined, and the ascending aorta is not visible on the right. The chest radiograph may appear normal or reflect the presence of associated lesions, such as increased pulmonary flow from a VSD or decreased pulmonary flow in the setting of pulmonary stenosis. Dextrocardia occurs in approximately 20% of these patients, and the diagnosis should be suspected if seen with abdominal situs solitus.

2.The typical electrocardiogram shows a left axis deviation. Among pediatric patients, there is loss of the usual Q waves in the precordial leads, with deep Q waves in leads II and aVF reflecting reverse septal activation. A variety of AV node conduction abnormalities may manifest with time and progress to complete heart block.

D.Diagnostic evaluation

1.In most instances, the diagnosis can be made with echocardiography. The essential findings of AV and ventriculoarterial discordance must be demonstrated. Imaging may be difficult in the presence of dextrocardia or mesocardia. Close attention must be paid to the morphologic details of each chamber.

a.The morphologic right ventricle is identified on the basis of its triangular shape, the presence of trabeculations and moderator band, an inferiorly positioned AV valve, and the presence of AV valve attachments to the interventricular septum.

b.The morphologic left ventricle is identified on the basis of its bullet shape, smooth wall, and more superiorly positioned AV valve and absence of AV valve attachments to the interventricular septum. In the case of ccTGA, these relationships are preserved but reversed.

c.Apical four-chamber and subcostal images are particularly helpful. The suprasternal notch view is essential in evaluating the great vessels that lie parallel to each other.

d.The aortic arch typically lies to the left of midline in the sagittal plane and can often be visualized from the high left parasternal position. Because variations in great vessel position occur, the spatial orientation must be clarified.

e.Associated defects (e.g., systemic AV valve insufficiency, VSD, and outflow tract obstruction) with ccTGA must be excluded or defined.

2.Catheterization is unnecessary for the diagnosis of ccTGA but may be helpful in preoperative planning with regard to the hemodynamic significance of associated lesions. In rare instances, ccTGA is diagnosed by catheterization and was not recognized during routine echocardiography. An unusual arterial catheter course is caused by the anterior and leftward position of the aorta in most instances. The left-sided coronary artery typically arises from the posterior sinus and assumes a right coronary branching distribution, whereas the right-sided coronary artery arises from the anterior and rightward sinus and assumes a typical left coronary branching distribution (Fig. 31.4). Because the ventricular septum often lies in the sagittal plane, ventriculography is usually best performed in the straight posteroanterior and lateral projections.

E.Therapy

1.Medical management is dictated primarily by the associated malformations.

a.In the rare case of isolated ccTGA, the risk of development of conduction abnormalities is cumulative over time; therefore, periodic Holter monitoring is warranted. Permanent pacemaker placement is often needed.

b.The systemic AV valve and ventricle may show signs of failure that necessitate initiation of heart failure measures in the form of diuretics and afterload reduction, although data are lacking on the use of agents such as ACE inhibitors or β-blockers in systemic right ventricles.

c.Associated lesions such as pulmonary stenosis or atresia, severe systemic AV valve regurgitation, or VSD may likewise contribute to the medical treatment of these patients, but often also necessitate surgical intervention.

d.The American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines do not recommend routine antibiotic prophylaxis for these patients unless they have had recent placement of prosthetic material within the preceding 6 months or have a leak at, or adjacent to, the site of a previous prosthesis.

2.Surgery

a.Infants and children who are brought to medical attention early often need surgical intervention in the form of relief of pulmonary outflow tract obstruction or placement of palliative shunts, depending on the associated lesions.

b.For selected children, a double switch procedure may be performed. An atrial switch corrects the AV discordance by baffling atrial blood to the appropriate ventricle (i.e., oxygenated blood diverted from the left atrium rightward to the right-sided left ventricle and vice versa by the Mustard or Senning procedure). Arterial switch is performed in the same operation to restore anatomic ventriculoarterial concordance. The double switch operation may necessitate a period of “training” of the left ventricle by means of pulmonary artery banding. The results of this operation are generally less favorable in older patients in whom the right ventricle has been the systemic ventricle for a more prolonged period. The intermediate-term results of this procedure are encouraging, but data for long-term results are limited. Those with a large VSD may undergo atrial baffling with a Rastelli operation (see Table 31.1).

c.Adult patients with symptoms of progressive systemic AV valvular insufficiency may need valve repair or replacement. Most centers that have reported results with this procedure have found improved functional status after surgical treatment and acceptable risks. The timing of surgical intervention among patients with less severe symptoms is a topic of debate, but it is agreed that referral should be considered early before irreversible changes in ventricular function occur.

IV.EBSTEIN ANOMALY. This anomaly of the tricuspid valve represents 0.5% of congenital heart defects. The natural history of this lesion varies from early death to nearly normal expected survival, depending on the degree of tricuspid valve involvement and the presence and type of arrhythmias. An increased risk of sudden death irrespective of functional class, presumably caused by arrhythmia, has been observed. Predictors of poor outcome include earlier age at presentation, cardiomegaly, severe RV outflow abnormalities, and disproportionate dilation of the right atrium relative to the other chambers. There is an association with maternal lithium administration, but most cases are sporadic.

A.Anatomy

1.The tricuspid valve is morphologically and functionally abnormal. The basic features include adherence of the septal and posterior leaflet to the myocardium, which lowers the functional annulus toward the RV apex. This results in the classic atrialization of the right ventricle (Fig. 31.5) and dilation of the true tricuspid annulus. The anterior leaflet is usually not displaced but is redundant and may be fenestrated and tethered.

FIGURE 31.5 Section through the right atrioventricular junction. A: Normal heart, showing the right atrium (A) and right ventricle (V). B: Mild degree of Ebstein anomaly. C: Severe Ebstein anomaly. In (B) and (C), there is apparent displacement of the tricuspid valve. (From Adams FH, Emmanouilides GC, Riemenschneider TA, eds. Moss’ Heart Disease in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1989, with permission.)

2.Associated structural anomalies include a PFO or ASD (found in ≥80%), VSD, mitral valve prolapse, and pulmonary stenosis. ccTGA is associated with Ebstein-like anomaly of the tricuspid (systemic) valve.

B.Clinical presentation

1.Signs and symptoms are variable.

a.The presence of a severely insufficient valve can be apparent at birth because of right-to-left shunting across a stretched PFO or ASD, resulting in cyanosis. Pulmonary vascular resistance is high in the neonate and worsens cyanosis, but as pulmonary vascular resistance falls, cyanosis may resolve. In adulthood, as tricuspid regurgitation becomes long-standing with associated decreased RV compliance, cyanosis can reappear. In subtle cases, the anomaly may not be evident until adulthood and then results in nonspecific fatigue, shortness of breath, palpitations, near-syncope, or syncope. In the presence of an interatrial communication, patients may present with paradoxical embolization or brain abscess. Because the spectrum of involvement varies greatly, a high index of suspicion must be maintained.

2.Physical examination

a.General inspection usually reveals normal jugular venous pulsations despite severe tricuspid regurgitation, which is masked by a large compliant atrium. Cyanosis may be present as a result of right-to-left shunting at the atrial level. Digital clubbing will vary depending on the amount of cyanosis.

b.The most common auscultatory findings are the regurgitant murmur of tricuspid insufficiency, gallop rhythms, multiple systolic ejection sounds, and a widely split S2.

C.Laboratory examination

1.Chest radiography may reveal cardiomegaly, caused by right atrial enlargement from tricuspid insufficiency. Typically, it is described as a globe-shaped heart with a narrow waist.

2.The electrocardiogram can demonstrate PR prolongation, right atrial enlargement (“Himalayan” P waves), and superior axis with or without right bundle branch block (Fig. 31.6). The QRS amplitude is characteristically low over the right precordial leads because of a diminutive right ventricle. The preexcitation pattern, if present, is almost always type B (i.e., left bundle branch pattern). Deep Q waves may be seen in leads II, III, and aVF from fibrotic thinning of the RV free wall and/or septal fibrosis.

FIGURE 31.6 Lead V1 of an electrocardiogram from a newborn infant with Ebstein anomaly demonstrates marked right atrial enlargement and an rSR′pattern.

D.Diagnostic evaluation

1.The diagnosis can be confirmed with transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiography, with the tricuspid valve readily visualized in the parasternal short-axis, apical four-chamber, and subcostal views.

a.Apical displacement of the septal leaflet from the insertion of the anterior mitral valve leaflet by at least 8 mm/m2 body surface area is considered diagnostic. In less obvious cases, only tethering of the septal leaflet may be found, defined as at least three accessory attachments of the leaflet to the ventricular wall causing restricted motion. An imperforate valve may rarely occur.

b.The anterior leaflet may produce functional obstruction of the pulmonary outflow tract. The leaflet in this circumstance is often called “sail-like.” The pulmonary outflow is carefully studied to discern functional obstruction from such a leaflet rather than true anatomic atresia of pulmonary outflow.

c.Views of the atrial septum are included in all studies to assess the size of the ASD and degree of shunting, if present.

d.The size of the right ventricle and true tricuspid annulus is assessed because size guides the feasibility of surgical intervention.

f.Associated lesions must be excluded, such as ASD, RV outflow tract obstruction, patent ductus arteriosus, and, in rare instances, mitral valve abnormalities with associated insufficiency.

2.Cardiac catheterization is unnecessary for the diagnostic evaluation of Ebstein anomaly, except to exclude coronary artery disease in adult patients with risk factors for whom surgical intervention is planned. Increased risk of cardiac arrest during catheterization has been reported. A diagnostic right heart study may be indicated in the presence of associated hemodynamic abnormalities as part of preoperative planning.

3.Formal electrophysiologic study may be considered for patients with arrhythmias or for those being considered for surgical treatment. Radiofrequency ablation of accessory pathways is performed.

E.Therapy

1.A large number of adult patients may undergo medical treatment, which includes standard heart failure medications such as diuretics and digoxin. There are no good data to support ACE inhibitors in right heart failure due to Ebstein anomaly. Particular attention must be focused on the management of atrial dysrhythmias, which become more common with age. Permanent pacemaker therapy is required in 3.7% of patients, mostly for AV block and rarely for sinus node dysfunction. Endocarditis prophylaxis is no longer recommended for these patients unless they are cyanotic and unrepaired, have undergone placement of prosthetic material within the preceding 6 months (i.e., ASD occluder device), have a leak adjacent to or at the site of prosthetic material, or have had tricuspid valve replacement.

2.Surgical correction is usually recommended for patients with NYHA functional class III–IV symptoms despite medical therapy. The tricuspid valve may be repaired primarily or complete replacement may be necessary, and an interatrial communication, if present, is closed. Patients with significant cardiomegaly, cyanosis, or arrhythmias are considered for surgical intervention. Favorable results have been achieved at centers experienced in the care of adult patients, and functional class has improved after therapy.

3.Transcatheter closure of an interatrial shunt can be considered in select patients with cyanosis at rest (oxygen saturation < 90%). Patient selection must be carefully evaluated, as closure of an ASD or PFO may lead to worsening RV dysfunction because of increased right-sided heart pressures. In the case of paradoxical embolic events (i.e., stroke), ASD/PFO closure is considered.

V.EISENMENGER SYNDROME. Eisenmenger syndrome is the clinical phenotype of an extreme form of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Over the last few decades, rapid advances in the modalities of diagnosis and treatment of congenital heart disease have resulted in the ability to repair defects at a much younger age. Pulmonary vascular injury is prevented in many of these children. However, Eisenmenger syndrome is still seen in older patients and occasionally in younger patients, particularly in those from developing countries where access to care may be limited. The natural history of Eisenmenger syndrome is variable; and although a cause of significant morbidity, many Eisenmenger patients survive 30 years or more after the onset of the syndrome.

A.Physiology. Patients with a systemic-to-pulmonary circulation connection will initially have left-to-right shunting of blood because of the lower pulmonary vascular resistance compared with systemic vascular resistance. Over time, because of excessive flow to the pulmonary vasculature, resulting in increased shear and circumferential stress, pulmonary vascular resistance increases. Eventually, the shunt reverses, creating right-to-left flow. Although the classic form of the disease was initially used to describe the long-term consequences of a VSD, it can occur with any congenital defect with an initial left-to-right shunt, including ASD, AV canal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, aortopulmonary window, and surgically created systemic-to-pulmonary artery shunts. It is important to note, however, that the physiology and clinical presentation differ depending on the level of shunt. In contrast to patients with nonrestrictive shunts at the ventricular or arterial level, most patients with ASDs do not develop Eisenmenger syndrome, and if they do, they present much later in life. In this case, atrial-level shunting is determined by the compliance of the ventricles and is not due to systemic or suprasystemic pulmonary artery pressures.

B.Clinical presentation of Eisenmenger syndrome has multiorgan involvement

1.Symptoms. Pulmonary congestion (from the left-to-right shunt) in early childhood may be evident from the history, but improves as the shunt reverses with ensuing cyanosis. Exercise intolerance is very common. Hypoxemia can lead to erythrocytosis and symptoms of hyperviscosity (e.g., headache, dizziness, fatigue, and cerebrovascular accidents). These patients can have a bleeding diathesis due to thrombocytopenia and inadequate clotting factors. This can complicate the management of intrapulmonary thrombosis, which occurs in up to one-third of patients. Hemoptysis is a common symptom—alone or caused by pulmonary infarction. Infectious complications include bacterial endocarditis and septic cerebral emboli. Atrial arrhythmias and symptoms of congestive heart failure are usually a late sign and are associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death.

2.Physical examination. The initial murmur of the associated lesion goes away with reversal of the shunt. Cyanosis and digital clubbing are present, and arterial pulses may be diminished. The cardiac examination reveals signs of elevated right heart pressure, such as jugular venous distention with a prominent v wave, a right parasternal heave, a loud pulmonary component of S2 (sometimes palpable), a right-sided S4, a holosystolic murmur of tricuspid regurgitation, and a diastolic decrescendo murmur of pulmonary regurgitation. Signs of congestive heart failure such as peripheral edema, ascites, and hepatosplenomegaly are seen later in the disease course.

C.Laboratory examination

1.Chest radiography is variable. It may show dilated, even calcified, central pulmonary arteries. Reduced peripheral lung markings are not commonly seen. Patients with ASDs tend to have cardiomegaly due to RV enlargement.

2.The electrocardiogram shows evidence of right atrial enlargement and RV hypertrophy. The presence of atrial arrhythmias should be investigated, particularly in the presence of palpitations.

D.Diagnostic evaluation

1.Echocardiography. Two-dimensional echocardiography helps in the detailed assessment of the level of the defect, associated lesions, and ventricular function. Doppler measurements can demonstrate and assess the size of the shunt as well as RV pressure and volume overload.

2.Cardiac catheterization. Cardiac catheterization is often necessary in these patients to assess the pulmonary vascular resistance. Demonstration of pulmonary vasoreactivity to oxygen, nitric oxide, or other pulmonary vasodilators is prognostic for these patients and can help identify which patients will most benefit from advanced therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension.

E.Therapy

1.Medical management

a.Chronic nocturnal oxygen therapy has not been shown to be beneficial, although it may improve symptoms in some patients. Anticoagulation is controversial because it can also predispose to hemorrhage or hemoptysis, but it is helpful in preventing thromboembolic events. Hyperviscosity can be managed in symptomatic patients by performing phlebotomy with isovolumic replenishment, but routine phlebotomy is contraindicated because of its effect on iron stores, oxygen-carrying capacity, and increased risk of stroke. Monitoring of iron levels and iron replacement, therefore, is paramount. The management of right-sided heart failure is problematic, and the use of digoxin in these patients is controversial. Diuretics should be used cautiously because aggressive diuresis predisposes to hyperviscosity and decreases preload. Endocarditis prophylaxis is warranted.

b.Over the last few years, the treatment of pulmonary hypertension in Eisenmenger syndrome has undergone a paradigm shift. While traditional therapy focused on preventive and palliative measures, there is accruing evidence to suggest that the disease is in fact modifiable and that selective pulmonary vasodilators are not only safe but likely beneficial in this population. These agents include endothelin antagonists, prostacyclin analogs, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. The only randomized, placebo-controlled trial performed to date in Eisenmenger patients, BREATHE-5, showed reduction in pulmonary vascular resistance and improvement in exercise capacity (with no detriment to oxygen saturation) using bosentan (an endothelin antagonist). In general, intravenous treatments are avoided in this population in view of the risk of paradoxical embolism and increased infectious risk with indwelling lines.

2.Surgical management. Selected patients may be candidates for combined heart–lung transplantation or lung transplantation with concomitant repair of the intracardiac defect, if feasible. Timing of these interventions may be difficult because of the relatively long-term survival of these patients after the onset of the disease process and the recent availability of selective pulmonary vasoactive therapy.

F.Eisenmenger syndrome in special situations

1.Travel to areas of high altitude should be avoided because it may result in acute right heart failure. Air travel, however, is not contraindicated, as cabin pressures during commercial flights are generally well tolerated.

2.Pregnancy in these patients is high risk to the fetus and the mother (>50% maternal mortality) and is generally contraindicated. Given the high risk of maternal and fetal mortality, contraceptive methods (preferably without the use of estrogen) are critical. Elective termination should be discussed with pregnant Eisenmenger patients.

3.Noncardiac surgery is also associated with high risk and should be performed under the supervision of anesthesiologists familiar with Eisenmenger syndrome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The authors thank Drs. Matthew Cavender, Richard Krasuski, Yuli Kim, Athar Qureshi, Keith Ellis, J. Donald Moore, and Douglas S. Moodie for their contributions to earlier editions of this chapter.

Landmark Articles

Galie N, Beghetti M, Gatzoulis MA, et al. Bosentan therapy in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circulation. 2006;114:48–54.

Gatzoulis MA, Balaji S, Webber SA. Risk factors for arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death late after repair of tetralogy of Fallot: a multicentre study. Lancet. 2000;356:975–981.

Presbitero P, Somerville J, Rabajoli F, et al. Corrected transposition of the great arteries without associated defects in adult patients: clinical profile and follow up. Br Heart J. 1995;74:57–59.

Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines on the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease). Developed in Collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(23):e143–e263.

Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116:1736–1754.

Key Reviews

Attenhofer Jost CH, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, et al. Ebstein’s anomaly. Circulation. 2007;115:277–285.

Warnes CA. Transposition of the great arteries. Circulation. 2006;114:2699–2709.

Relevant Book Chapters

Freedom RM, Dyck JD. Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. In: Allen HD, Gutgesell HP, Clark EB, et al, eds. Moss and Adams’ Heart Disease in Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Including the Fetus and Young Adult. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1085–1101.

Gatzoulis MA. Tetralogy of Fallot. In: Gatzoulis MA, Webb GD, Daubeney PEF, eds. Diagnosis and Management of Adult Congenital Heart Disease. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2003:315–326.