The fight for survival has made, and continues to make, a profound impact on the Israeli psyche. With one exception (the prosecution of the 1982 war in Lebanon) there has always been consensus among Israelis about the threat to their country’s existence and the fate in store for them should they lower their guard.

This is not so with regard to the occupation of the West Bank. Over the years, the right-wing’s vision of a “greater Israel” has been eroded, and today views range from those of a small minority of far right-wingers, who still cling to their maximalist dream, through those of the vast majority, who would like, with the exception of East Jerusalem and the Old City, to end the occupation and retain only those areas vital to Israel’s security, to a small left-wing minority who would like to return to the 1967 borders with minor changes.

Like many other countries, Israel has some extreme elements on both ends of the political spectrum, whose activities attract a disproportionately large amount of publicity compared to the level of support they actually receive. These include, on the right wing, the so-called “Hilltop Youth,” who sometimes establish unauthorized outposts outside existing West Bank settlements. Some of these young people have been linked to “price-tag” attacks on Muslim and Christian property and even, on occasion, the IDF, and the government has set up a unit specifically to deal with the problem. The attacks are widely condemned by most Israelis, including other residents of West Bank settlements. The left-wing Gush Shalom movement, meanwhile, is also viewed as extreme and controversial by mainstream Israeli opinion because it supports soldiers’ refusal to serve in the West Bank and has sent a relief convoy to Gaza.

“Negotiation Fatigue”

Israelis have watched through the years as American presidents and their appointed Middle East negotiators have come, attempted to advance the peace process, and gone, with varying degrees of success. Every Israeli wants to live in peace with the Palestinians, but quite how this will ever be achieved is not clear. By now, more than two decades after the signing of the Oslo Accords, which were meant to bring peace, it is not surprising that Israelis have “negotiation fatigue.” Most still favor a two-state solution, but the negotiations simply bring demands and counter-demands, with no real end to the conflict in sight.

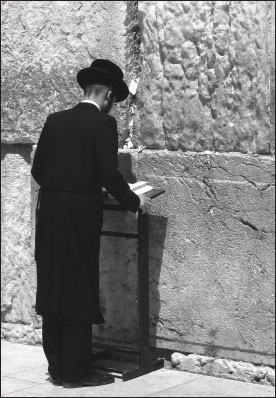

Israel’s Jewish population is generally thought of as consisting of two groups, religious and secular, with the latter dominant. In fact, Israeli Jews are divided into four groups. The smallest group, the black-hatted, black-coated ultra-Orthodox or Haredi community, in 2017 amounted to about 9 percent of the total population, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics. But the projected percentage is much higher, because in 2012–13 almost 30 percent of children in Jewish Israeli schools were ultra-Orthodox. The religious parties in parliament wield considerable power because their general lack of interest in the larger picture makes them potentially flexible coalition partners. Money is basically what they are interested in, to fund their schools, charities, and community welfare projects, and if they get it they are satisfied.

Since the founding of the State of Israel, when there were just 400 yeshiva (seminary) students, Haredi men have been exempt from military service. In 2014, a bill was passed stipulating that yeshiva students will be enlisted from 2018, and criminal sanctions will be imposed on draft dodgers. The bill was an election promise by Yair Lapid (whose Yesh Atid party spearheaded the legislation) that Haredim would have to “share the burden” of army service. The issue lies at the heart of a cultural war over the place of the ultra-Orthodox in Israeli society. Haredim say conscription threatens their community, and they insist their young men are serving the Jewish people—through prayer and learning.

Two other groups combine to form the religious Zionists, whose male members almost universally wear knitted skullcaps (kippot), and who observe, to the letter, the tenets and traditions of the Jewish religion as laid down in the Scriptures and interpreted by their rabbis. The 2017 Central Bureau of Statistics survey found that people defining themselves as either religious or religious traditionalists comprise about 23 percent of the population. They serve in the army, many attaining high rank, and are identified with the right wing in the political arena. Most of the settlers evacuated from Gaza in 2005 belong to this group.

The third group, around 24 percent, comprises “traditionalists who are not so religious.” They observe those practices that suit their lifestyle, and make their children aware of their traditions, but oppose a formal reformation of the Jewish religion, believing it to be unnecessary and negative. At the back of their minds is the thought, perhaps, that an intact Judaism kept its adherents going for more than two thousand years, and question whether a watered-down version would do as well. Where’s the harm in leaving it the way it is?

And finally there are the secular—44 percent of the total—who are perhaps not as secular as they claim to be. Looking at the survey, religious or traditional Jewish practice intrudes quite substantially on secular Israeli life. Almost every Jewish male is circumcised, and almost without exception every Jewish home has a mezuzah (a little parchment scroll of prayer in a case) affixed to the doorpost of the house. Fewer than 20 percent of thirteen-year-old Jewish Israeli boys do not celebrate bar mitzvah, fewer than 20 percent do not have Jewish wedding ceremonies and burials, and 95 percent always or sometimes participate in the annual Passover celebration. Some secular Jews actually fast on the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) and almost a third, sometimes or always, observe the dietary laws of Kashrut in their homes. The secular claim that these anomalies arise out of family values rather than belief. Perhaps, but more than 87 percent of Israeli Jews believe that there is a God, and roughly the same number think it may be true that the Ten Commandants were given to Moses on Mount Sinai—all of which has nothing to do with family values. These statistics emerge from a survey by the prestigious Guttman Institute of Applied Social Research, first published in 1993.

An interesting fact is that the so-called secular 44 percent of the Jewish population provides almost all of Israel’s leaders in politics, business, the free professions, and academe. They are overwhelmingly from Eastern or Central Europe (immigrants themselves, or descendants of immigrants) as opposed to countries on the Mediterranean rim. This is the segment that is largely responsible—through influence, connections, and language—for Israel’s image as a liberal, free, and unfettered society.

Israel’s minorities—Arabs, Muslim and Christian, Druze, Circassians, and non-Arab Christians from Armenian to Mormon—each have their own belief systems and religious practices.

The Diaspora-based Jewish Reform and Conservative movements also contribute to Israel’s religious pluralism. A small but growing percentage of native-born Israelis, almost all from secular backgrounds, are identifying either with Conservative or Reform Judaism. A survey by the Israeli Democracy Institute in Jerusalem in 2013 found that 3.2 percent of Israelis see themselves as affiliated with the Conservative movement, and 3.9 percent with the Reform movement. The figures may show only a very gradual trend, but they indicate a new awareness among secular Israelis of their Jewish identity.

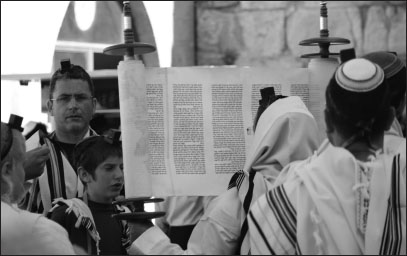

For many years, on the first day of every Jewish month (Rosh Chodesh), a group of Jewish women has been holding prayer services at the Western Wall (the Kotel). The women pray and read from the Torah collectively and out loud at the Wall, and wear prayer shawls and phylacteries, traditionally worn only by men. This is deemed unacceptable by the Orthodox establishment and on occasion there have been heated demonstrations against the women. Negotiations are in progress to find a designated egalitarian prayer space within the confines of the Western Wall area; however, perceived government foot-dragging at the behest of Israel’s Orthodox rabbinate has become a point of tension between Israel and the Diaspora communities. The issue threatens to widen the wedge even further between the two sides unless a resolution is found.

The effect of all this religion on the visitor is slight and is in general to be found in two areas, that of Kashrut, the Jewish dietary laws, and that of observance of the Sabbath (Shabbat). In addition to the prohibition of all pork products, shellfish, and any other fish without scales, the dietary laws require the strict separation of meat and milk in the kitchen and on the table. No dairy product may be served after meat. Kosher restaurants serve either meat or dairy menus, which means that after a meat meal you cannot have real ice cream or cream with your dessert or milk in your coffee.

Hotels in religious areas follow the dietary laws to the letter. Hotel breakfasts are traditionally milk-based, so if you expect to find any meat products on the breakfast table you will be disappointed. Most tourists find that the lavish Israeli breakfast buffet, with its abundance of salads, cheeses, eggs, smoked fish, breads, pastries, and dairy delicacies offers more than enough, but those craving bacon can find nonkosher restaurants without difficulty near hotels and in areas frequented by tourists.

Shabbat commences at sunset on Friday evening and ends at sunset on Saturday. For the religious, the Sabbath is a day of rest, and no driving, cooking, or work of any kind is permitted—no answering of telephones, no switching on or off of lights or other electrical equipment. One may not even press a button to summon an elevator. In hotels an electronically programmed Shabbat elevator moves up and down automatically, stopping at every floor, throughout the day. While intercity taxi shuttles do run, bar Haifa there is no public transportation, and most shops remain shut on Shabbat. But the beaches are open, as are most places of entertainment, cafés, clubs, and nonkosher restaurants. In Jerusalem access to certain areas may be blocked by the ultra-Orthodox.

So don’t expect to travel by bus or train on Saturday, don’t plan a shopping expedition for Saturday, and don’t be surprised if your religious friends or business associates don’t call you or answer their own phones on a Saturday.

In Israeli society traditional gender roles, where women are wives and mothers and men are the primary breadwinners, are still perceived as the ideal. Despite the fact that dual-income families are common, with a high percentage of women in the labor force working to contribute to their family’s standard of living, fewer women than men actually strive to pursue independent careers. And even in the case of those women who earn high salaries, hold top positions in their professions or corporations, or own their own businesses, it is still the woman in the family who is responsible for household management and bringing up the children. The emancipated man will “help” with these chores.

In spite of this ideal, people are marrying later, divorce is on the rise, premarital sexual relations are by and large accepted by the loosely traditional and the secular, and unmarried couples living together have become common. With the emphasis on the importance of having children and on increased financial independence for women, the number of single-parent families is growing, and there is little stigma attached to these, or to same-sex couples. In 2017, the state promised legislation awarding same-sex couples the right to adopt.

The family remains a major factor in Israeli life. Friday night is the big night for family gatherings, when children and grandchildren converge on parents and grandparents for the Sabbath meal. Geography helps—because of its size, nowhere in Israel is too far to make the journey for the Shabbat get-together, and in some cases (especially in the case of the religious who don’t drive on Shabbat) the family will sleep over. The gathering may be held at different family members’ houses, and friends, visitors, and extended family are often invited.

In secular homes the get-together may be for lunch on Friday or brunch on Saturday. Non-religious families often meet for lunch at a restaurant on Saturdays, and a familiar sight over the weekend is that of long tables with guests shouting at each other from one end to the other, and children running around. The weekend gettogethers are repeated on the Jewish holidays.

Grandparents often play a role in helping with children, taking them to and from school, friends, and after-school activities, and, of course, babysitting, as well as giving financial support. Exchanging presents is ongoing, with Israelis giving generous gifts to celebrate every occasion.

It is a great compliment to be called a hevreman (an outgoing, sociable person). A gregarious people, Israelis form deep and lasting friendships, at school, in the neighborhood, but most importantly in the army, where the quality of loyalty is ingrained. After army service many youngsters travel together to the far corners of the earth. As young couples, married or about to be, they are surrounded by friends, some from her side, some from his. They go on trips (tiyulim) to the countryside together, picnic together, go to the beach together, go pubbing together, and eat out at restaurants together. When they have their own homes they entertain the hevre (their circle of friends) at coffee and cake evenings enlivened by jokes, political arguments, and the swapping of recent experiences, good and bad.

The old boys’ network, built and maintained by group friendships, results in widespread “jobs for pals” favoritism, in government, municipalities, public utilities, fully or partially state-owned monopolies, and business generally.

On the macro level Israelis have a high regard for each other, and few things give an Israeli more pleasure than a fellow countryman’s success. As a nation they regard themselves as being flexible, resourceful, generous, direct, patriotic, courageous, warm, and easy to please. On the other hand, they acknowledge that they may be overconfident, bad listeners, a bit abrasive, risk takers, and even somewhat lawless—traits that they don’t regard as particularly important anyway.

On the micro level it is quite different, and other than toward those in their inner circle, Israelis tend to be competitive, judgmental, and critical of each other. They rarely pay compliments or give credit to each other, and there is a Hebrew expression “simha l’ed” that describes the pleasure derived from another’s misfortune.

Epithets such as stupid (tipesh, metumtam, idiot), sucker (freier), crook (ganav), and madman (meshugah) are freely used to describe their fellows without compunction. Because of the pressures of life in this beleaguered country and the tensions they produce, negative first impressions are often hastily formed.

Other factors influence the attitudes of Israelis toward each other. The older generations still retain their pre-immigration prejudices, with Lithuanians looking down on Poles and vice versa; German Jews feeling superior to everyone else and being regarded as rigid and snobbish in return; Western newcomers condescending to those from the East, and so on through the different backgrounds of those who make up the ethnic mosaic of the country.

Egocentricity is part of the Israeli character, and most Israelis show varying degrees of competitiveness. They don’t suffer fools gladly, and the gullible are scorned. In the early years of the State, this trait was to some extent contained by the prevailing socialist and egalitarian ethos, but with the dissipation of those ideals it became every man for himself, “Im ayn ani li, mi li?” (“If I am not for myself, who will be for me?”) In times of national crisis, however, this attitude immediately gives way to selfless cooperation, and Israeli solidarity becomes impenetrable.

In Israel, Ashkenazim, those Jews originating in Central and Eastern Europe—whose liturgy follows the German (Ashkenaz) rite—are ambivalent toward the Sephardim—who follow the liturgical rite of Spain (Sepharad)—who came mainly from Arab and Muslim lands; and these Sephardim don’t have much love for the Ashkenazim, and in fact have a history of grievances against them.

Sabras, native-born Israelis, have on the rational level largely abandoned their parents’ prejudices, but in cases of confrontation the old attitudes can bubble to the surface. Also the many areas of contention, particularly in politics and religion, and in many areas the high density of population made up of people of different backgrounds with different norms of behavior, can lead to friction that would be absent in more spacious and homogeneous environments.

On the other hand, Israelis tend not to harbor grievances, are quickly willing to change their unfavorable first impressions, to try again, to forgive and forget, and make friends.

Attitudes toward Israel’s minorities vary. They are generally amicable toward non-Arab Christians, Druze, and Circassians. Toward Israeli Arabs, they run the gamut from suspicion and distrust on the part of the Ashkenazim to dislike and sometimes outright hatred on the part of many of the Sephardim originating in Arab countries where Jews were persecuted. Christian Israeli Arabs on the whole come off better.

Despite the ongoing conflict in the region, which complicates relationships between Jews and Arabs, there is a surprising amount of warm interaction between Arab and Jewish businessmen, Arab restaurateurs and shopkeepers and their clients, and Arab and Jewish coworkers in tourism, agriculture, industry, and commerce. In the arts, media, and elsewhere—particularly in the numerous associations and interfaith projects where Jewish and Arab Israelis, and even Palestinians, work together for common causes, including peace, plurality, human rights, and democracy—Arabs and Jews form deep friendships.

Invited to a Muslim wedding ceremony by an Arab Israeli notable, the Jewish guests at the reception were surprised and impressed when, seated at tables with other Jewish guests, they were given baskets containing bottles of wine and whiskey by the male members of the host’s family, even though according to Islam alcohol is strictly forbidden. “Celebrate with us in your own way,” said the father of the groom, their gracious host.

Of all the wars that Israel has fought since its creation, the Second Intifada was in many ways the most terrifying. For several years, the whole country was the frontline as suicide bombers murdered and maimed thousands of Israeli civilians on buses, in cafés, and in markets. Israelis feel they were not given sufficient acknowledgement by the outside world as victims in that conflict.

The Intifada tested the resolve of the many Israelis who had worked to promote Jewish and Arab coexistence, and even those on the left of the political spectrum became suspicious about the Palestinians’ true intentions. This has not so easily waned over the years, unfortunately, and people remain scarred.

Humor is the great defense mechanism. Throughout their history, laughter has helped the Jews survive disaster, and enabled them to cope with everyday hardships. The basis of Jewish humor is “Hochmat haim” (the wisdom of life), and is universal. Jews laugh at themselves, at life’s absurdities, and at man’s frailties. Israeli humor is more esoteric. Masters at last in their own land, Israelis laugh more at everyday situations and less at the universal human condition. Their jokes tend to be based on the political, social, and economic situation, current events, and people. Every new wave of immigrants is grist to the humor mill; today’s news is tomorrow’s joke. Israelis are excellent satirists and in the secular Israeli world nothing is sacred. They prefer to laugh at others rather than at themselves. They enjoy making fun of each other, their pretensions, their ethnic backgrounds, their idols, and their credos. Television programs and print media parody corruption in government, sports, big business, the military. Nothing is sacrosanct. Slapstick comedy is popular, as is sexual innuendo.