Jewish festivals are celebrated according to the Hebrew calendar—consisting of twelve lunar months set in the framework of a solar year—and not according to the Gregorian calendar. All Jewish festivals begin at sunset on the preceding day and end at dusk on the holiday.

Usually falling in September, the two-day New Year’s festival initiates ten days of penitence and soul-searching. The liturgy describes God as a heavenly king sitting on His throne and determining the destiny of each individual in the year ahead. Prayers of repentance are for mercy and a “good” new year, and in order to show trust in His compassion, Jews celebrate the festival with joy. As on the Sabbath, business in Israel closes down over the Rosh ha-Shana holiday. After attending synagogue with the traditional sounding of the shofar, the ram’s horn, families get together for a sumptuous evening meal. The candles have been lit at sunset when the festival begins, and the table is bedecked with apples, pomegranates, and honey, which symbolize a happy, fruitful, and sweet year. Families exchange gifts and New Year cards and e-mail messages are sent out prior to the holiday to friends and business acquaintances. “Shana Tova” (“a good year”) is the traditional greeting.

Eight days after Rosh ha-Shana is Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish year, a day of fasting, prayer, confession, and repentance of past sins both against God and against one’s fellow men. From its commencement at dusk until the appearance of the first stars the next night, everything shuts down for twenty-five hours, including radio and television, and the roads are clear of cars. Synagogues are crowded. No one drives on Yom Kippur, and children from secular families come out in droves to cycle with impunity down the normally traffic-filled streets. Hotels serve a limited room service menu to guests who are not fasting. The traditional greeting is “Gmar Hatima Tova,” which means, roughly, “May you be well inscribed in the Book of Life.” The evening service ends with the blowing of the shofar.

Five days after Yom Kippur the happiest of the biblical festivals, Sukkot, the feast of Tabernacles, celebrates God’s bounty and protection. It celebrates the Exodus from Egypt and the ingathering of the fall harvest, the start of the agricultural year, and the first rains. To commemorate the temporary shelters the Israelites dwelt in when they wandered in the desert, throughout Israel thousands of tabernacles, or sukkot (singular, sukkah), spring up. These are simple, boothlike structures roofed with palm fronds, citron, myrtle sprigs, and willow branches, in which families gather and in which all meals are eaten until the next festival, Simhat Torah, eight days later (see below). During this period schools are closed and many shops and businesses operate half days. The traditional greeting is Hag Sameah, “Happy holiday.”

Alfresco

As soon as Yom Kippur’s palpable sound of silence comes to an end, there is the unmistakable clank of sukkot being put together in preparation for Sukkot. By the next morning, sukkot have sprung up all over town, including on apartment balconies specially designed to fulfill the requirement in Jewish law of seeing the stars above the sukkah, rather than the upstairs balcony. You might even find a sukkah outside a non-kosher pub as all the festivals are marked—and enjoyed—by both religious and secular Israelis.

This holiday, the “rejoicing of the Law,” celebrates the conclusion of the annual reading of the Torah (the five books of Moses) and the renewal of the Torah reading cycle. A feature of this festival is the joyful dancing of Orthodox and religious Jews with Torah scrolls in their arms, while chanting the concluding chapters of Deuteronomy and the opening chapters of Genesis. Children are given sweets at the conclusion of the synagogue services.

At this time of the year Israelis talk about “before” or “after the hagim (holidays).” Little is done before; everything is postponed until after. So if you plan a business trip between Rosh ha-Shana and Simhat Torah, take this into consideration.

Hanukkah, the postbiblical festival of lights, usually falls in December. It celebrates the victory of the Jews under the leadership of the Maccabees in the second century BCE over the Greek Seleucids, who had desecrated the Jerusalem Temple. The festival lasts for eight days and is marked by the nightly lighting of candles to commemorate the miracle of the Temple, when a small supply of sacramental olive oil, only sufficient to rekindle the Temple menorah (candelabrum) for one day, lasted for eight days. Schools are closed but otherwise business is as usual. Every evening families and friends gather for the candle-lighting ceremony, one candle for the first night, two for the second, until the last night when the hanukiah, the eight-branched candle holder, is a splendid sight with all eight candles alight. There are holiday songs and traditional goodies fried in oil, such as doughnuts and potato latkes (fritters), are served. Children are given presents, typically a spinning top (dreidl) and coins (“hanukkah gelt”).

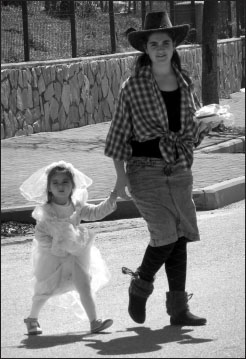

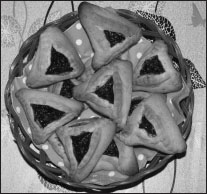

Purim falls in early spring, usually in March. Everyone’s, especially the children’s, favorite festival, it celebrates the deliverance of the Jews in Persia in the fifth century BCE by Esther, the beautiful Jewish queen of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes I), and her cousin Mordecai, from the genocidal plans of the evil prime minister Haman. Merriment is mandatory on Purim. To show that things are not what they seem, and that God works in mysterious ways, fancy dress and parody of authority are permitted, with children and often adults dressed up in colorful Purim costumes turning the streets into a Mardi Gras. Three-cornered buns known as hamantaschen are eaten. There are fancy dress parties at schools and in homes, and the countryside, bright with spring flowers, is filled with picnicking families and friends.

This important festival usually falls in April. Celebrated by religious and secular alike, Passover commemorates the redemption of the Children of Israel from their bondage in Egypt. The weeklong festival, during which schools are closed and businesses work half days, commences with the ritual seder meal. On this “night different from any other night,” families and extended families gather together for a feast at which the Hagaddah text, recounting the Exodus story of slavery and freedom, is read aloud together, and songs of praise are sung to the Lord. No bread, flour, or any other products containing leaven (yeast) may be consumed during Passover, and bread is replaced by matza, the unleavened “bread of affliction” eaten by the Israelites in Egypt.

Many hotels organize communal Seders for their guests and outside visitors. The last line of the Hagaddah promises “Next year in Jerusalem,” and Jews worldwide look forward to spending this spring festival in Israel. Passover is understandably Israel’s highest tourist season. The first and last days of the festival are public holidays.

The thirty-third day of the counting of the Omer (sheaf of the new barley harvest), in the seven weeks from Pesah to Shavu’ot, is a festive break in a period of mourning. Weddings are allowed, music is enjoyed, and the devout make a pilgrimage to the tomb of the second-century mystic Shimon Bar Yochai, in Meron, near Safed. Bonfires are lit and three-year-old Orthodox boys receive their first haircut.

You know Lag B’Omer is approaching when there’s a distinct shortage of supermarket trolleys. They will most likely have been commandeered by youngsters who roam streets and building sites searching for wood and other suitable bonfire material, which is then loaded onto the trolleys and stored in a safe place until Lag B’Omer. The bonfires are lit to celebrate the immense light brought into the world by Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, who died on Lag B’Omer. It’s advisable to keep all windows closed that night, as the custom is taken very seriously across the whole country.

Shavu’ot (Pentecost) usually falls in May. Originally the festival of the wheat harvest, it celebrates the revelation of the Ten Commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai. This is a joyous holiday when synagogues are decorated with flowers, many kibbutzim put on plays and other forms of entertainment, and children are dressed in white and crowned with floral wreaths. Dairy foods such as blintzes and cheesecake are traditional fare.

Falling shortly after Passover, the day is dedicated to the memory of the six and a half million Jews who perished in the Holocaust, and to those who resisted, whether individually in the camps, in uprisings against the Nazis, or fighting with the partisans. A siren is sounded at 10:00 a.m. and the nation stands to attention and observes two minutes’ silence.

A week after mourning the victims of the Holocaust, Israel pays tribute to the sons and daughters who fell in defense of the State. At 8:00 p.m. on the eve of Remembrance Day and at 10:00 a.m. the following morning, sirens are sounded and a two-minute silence is observed. Restaurants and places of entertainment are closed.

Celebrations of the anniversary of the proclamation of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948, begin at sunset on the Day of Remembrance. Israel’s Independence Day is a true public holiday, a day for parties, trips into the countryside, barbecues and get-togethers. In the early years of the State the day was marked by military parades, which have since been replaced by flypasts and naval displays.

For Muslims the most sacred festival is possibly Eid el-Adha, which commemorates Abraham’s sacrifice of a ram instead of his son (in Islam, Ismail, rather than Isaac).

Ramadan, the ninth month of the lunar Muslim calendar, is when the Koran is said to have been revealed to the prophet Mohammed by the angel Gabriel. During this month Muslims fast from sunrise to sunset. The end of Ramadan is marked by the three-day feast of Eid el-Fitr. Fridays and the festivals of Islam are official Muslim holidays.

The Christian holidays are celebrated by their communities, with different denominations celebrating on different dates. Easter and Christmas, are of course, the most important festivals. There is a Christian Information Center in Jerusalem.

A boy is formally named eight days after the birth as part of the ritual of circumcision (brith milah). A girl is formally named on the first Sabbath after the birth (britha).

On the eighth day after birth the foreskin is removed from the baby boy’s penis at a ceremony conducted either at home or in a function hall in the presence of family and friends. The surgery is performed by a mohel, a trained ritual circumciser, after which all the guests are invited to partake in a celebratory meal. The word brith means pact, or covenant, and the ritual goes back to God’s covenant with Abraham and confirms the status of the child as a member of the Jewish people. If the child is premature, or is not well, the brith may be postponed. Parties held to celebrate the event range from intimate at-home affairs with family and close friends to catered events. In secular circles it is becoming fashionable to have the brith ceremony at home and a party at a later date.

This ancient Levitical ritual, confirming that the firstborn son belongs to God, takes place after the child is thirty days old. After the priestly blessing, a party is held to celebrate the occasion.

On turning thirteen a boy is considered a responsible adult for most religious purposes, and the same applies to a girl when she turns twelve. They are now duty bound to observe the Commandments. In the bar mitzvah ceremony that marks this transition the boy is called up to the reading of the Torah. This is an important milestone in the life of the family. Following the religious ceremony, in the synagogue or at the Western Wall, a kiddush reception is held. The event may also be celebrated at a festive lunch or dinner, to which not only family and friends but also clients, employers, colleagues, professional associates, and acquaintances may be invited. All arrive bearing generous gifts or checks.

Bat mitzvahs are also celebrated, but usually more modestly, often for a number of girls together, and with smaller events

Other than in the case of the ultra-Orthodox, courtship follows much the same pattern as it does elsewhere in the Western world. Boy meets girl, they like each other, date a while, develop an intimate relationship, move in and live together, and finally decide to get married. Or they part and start all over again with someone else.

For the ultra-Orthodox it is quite different. Matchmakers are generally used to introduce young people, and a first meeting takes place in a public area such as a hotel lobby, or is strictly chaperoned, to find out if they are compatible. Over a modest glass of mineral water or Coke they ask each other questions and reveal their aspirations and goals in life. If they feel that they are suited there are further meetings, followed by family negotiations over marriage settlements, and the marriage takes place.

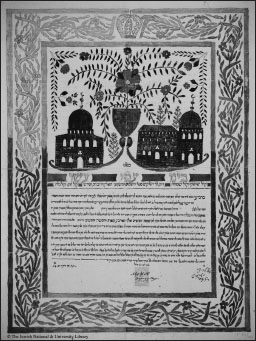

The minimum requirement for a religious Jewish marriage (there are no civil marriages in Israel) is a rabbi, a huppah (wedding canopy), the giving or exchange of rings, and marriage vows in the presence of two witnesses. The young couple, their parents, and the rabbi stand under the huppah, which is open at the sides and supported by poles at the four corners held by close family members or friends. After the betrothal blessings and the giving of the ring, the ketubah, or marriage contract—written in Aramaic and signed by two witnesses—is traditionally read out loud. This is followed by the sheva brachot, or seven blessings. Once the groom has kissed his bride, he stamps on a glass (normally wrapped in a napkin), shattering it—a reminder of the sadness felt at the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, or that happiness can never be complete.

The wedding reception is a huge and jolly affair. In the case of the ultra-Orthodox, men and women are separated for both dining and dancing, in the same way as they are separated in the synagogue. These receptions are lavish occasions, and gifts are often extremely generous to help defray the costs when the parents are not well-off.

The costs of the wedding are usually shared by both sets of parents. Venues proliferate, with wedding halls in the cities, outdoors in orchards or orange groves, in kibbutzim, on the seashore, or the fertile coastal plain, often requiring guests to drive long distances to participate. After all the toasts and revelry, driving home is no pleasure. Some young secular couples go abroad to marry in a civil ceremony (Cyprus is a popular destination) and hold a wedding reception on their return home.

Jewish traditions relating to death and mourning have two purposes: to show respect for the dead, and to comfort the living.

The practicalities are attended to by the hevra kaddisha, the burial society, whose cemeteries are found throughout the country, some like English graveyards but most with tombstones laid out like soldiers in rows one next to the other; some have shady trees, others not. Nondenominational cemeteries, quite costly, are also spread throughout the country, mostly in the grounds of kibbutzim, where there is greater peace and beauty.

Following the funeral, the bereaved keep seven days of intense mourning, called shivah. Parents, children, spouse, and siblings of the deceased gather together, usually in the deceased’s home, to give full expression to their grief, and slowly begin the journey back to everyday life. During the seven days, friends, neighbors, relatives, and colleagues call to offer their condolences, many bringing cakes and meals so that the mourners need not bother with cooking.