CHAPTER 6

Wisdom vs.

Intelligence

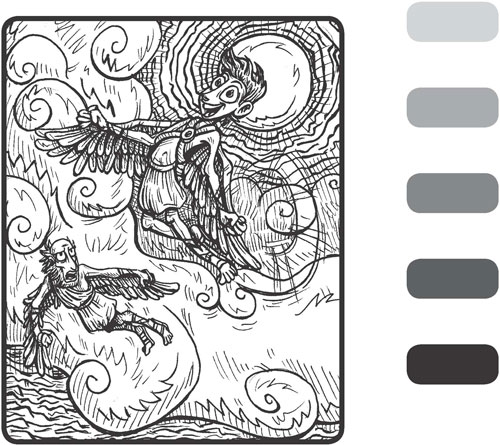

DAEDALUS AND ICARUS

Cast Daedalus Famous inventor | Icarus His young son Minos King of Crete |

NARRATOR: For 18 years, the inventor Daedalus had lived on the island of Crete and served the Bull-King Minos. In the king’s service, Daedalus had designed fast ships that allowed Crete to subdue the mainland city-states, a beautiful dancing floor for the princess, and, his greatest creation of all, the Labyrinth—a subterranean maze filled with twisting passageways, sudden drop-offs, and every kind of perilous trap. At its center lived the Minotaur, the half-man, half-bull creature that Minos had imprisoned there. Yet Daedalus gradually realized that he, too, was trapped. With every new invention he became more and more valuable to the king, who would never allow him to leave Crete alive.

DAEDALUS: All of my genius—all of my skill—and still I am helpless.

NARRATOR: Daedalus was making his way back to his workshop built atop the cliffs of Crete, a lodging that he shared with his son Icarus. He heard his son’s cries as he neared his home. Icarus would be 7 next spring. How many years had he wasted in the service of this tyrant?

ICARUS: (happily) Father!

DAEDALUS: How will I tell Icarus? He’ll never see our homeland. He’ll never see Greece.

ICARUS: Father, what did the king say? Did he say we can sail for the mainland?

DAEDALUS: I’m afraid not, Icarus. We can never leave this island.

ICARUS: Why not?

DAEDALUS: Because King Minos is strong, and your old father is weak.

ICARUS: We could steal a ship!

DAEDALUS: Are you kidding? Minos controls the seas, and I helped him. I’m trapped in a web of my own making.

ICARUS: There must be some way.

DAEDALUS: Icarus, it’s impossible! It’s just better to accept it now than later.

NARRATOR: The next few days brought a terrible melancholy on Daedalus. He gazed listlessly around his cluttered workshop. It was filled with useless wonders and trinkets. The Labyrinth had been his masterwork, but it had ultimately trapped even him.

ICARUS: Father, what’s wrong? Why don’t you come out to the cliffs with me? Play your pipes! It will make you feel better.

NARRATOR: Daedalus looked up and smiled at his son.

DAEDALUS: At least we are together, Icarus. Just let me grab my pipes.

NARRATOR: Overlooking the sheer drop to the sea, father and son seated themselves on a pair of rocks. Overhead the gulls were soaring in the breeze.

ICARUS: Look at the birds, father! Why can’t we fly like them?

DAEDALUS: (laugh) That is not the way the gods intended it. Oh, but if we could, we would be gone from this cursed island.

NARRATOR: The inventor paused and thoughtfully examined his shepherd’s pipe.

DAEDALUS: (breathlessly) Is it possible?

NARRATOR: He stared at the pattern of the pipe-reeds, each one longer than the one before. He glanced to the birds wheeling above. He saw the same pattern there in the elegant curvature of their wings.

ICARUS: (yelling) Look at me, father! Look at me!

NARRATOR: Icarus jumped up from his rock, his arms widespread, mimicking the wheeling of the birds overhead.

DAEDALUS: Quick, Icarus! Back to the house!

NARRATOR: Once there Daedalus dug furiously through the piles of supplies that littered his shop. He found several lengths of string—some for him and some for Icarus.

DAEDALUS: (excitedly) Tie this! Tie the end like this—into a loop.

ICARUS: What for, father?

DAEDALUS: To snare the gulls.

ICARUS: Why?

DAEDALUS: Just do as I say!

NARRATOR: Daedalus gleefully knotted a loop in his string.

DAEDALUS: Do you have yours? Good! Now back to the cliffs!

NARRATOR: Back on the cliffs, father and son laid their makeshift snares and baited them for the gulls.

DAEDALUS: Easy, son. Wait until they have eaten almost all the bait and suspect nothing and then pull the string tight. Only when they take off again will they realize that they are snared.

NARRATOR: They caught gull after gull. Daedalus knocked each on the head with a rock and placed the bodies into a large sack at his side. After a while, Daedalus noticed that Icarus was no longer springing his snares.

DAEDALUS: What’s the matter, son?

ICARUS: I’m tired of this game.

DAEDALUS: It’s not a game, Icarus. This is how we’re going to escape this island.

ICARUS: I feel sorry for the birds. Why must they die?

DAEDALUS: Every creature dies eventually, Icarus. Now is simply their time. See how some of the birds never give our traps a second glance?

ICARUS: Yes?

DAEDALUS: Those are the wise birds. Only the foolish birds, the ones that are too curious for their own good, come close enough for us to catch. We are teaching them a lesson.

ICARUS: But they’re dying—just for one little mistake.

DAEDALUS: It’s the way of the world.

NARRATOR: The sack was bulging now. Daedalus hoisted it over his shoulder and carried it back to their workshop. He heated a great jar of water and boiled every gull body to loosen the feathers.

DAEDALUS: After the bodies are boiled, the feathers will pull free—like so. Start plucking! We should have enough feathers here for my plan.

NARRATOR: Icarus plucked and said nothing. Daedalus worked late into the night, fashioning frames from green limbs that resembled the wings of birds. Using melted wax, he attached the gull feathers to these frames. He built two leather harnesses and attached to these his newly made wings. When Icarus awoke, he stared in amazement at his father who now wore an impressive wingspan.

ICARUS: You’re going to fly, father! You’re really going to fly!

DAEDALUS: Yes, Icarus. And you will too.

NARRATOR: Only then did Icarus notice a second pair of wings, one much smaller and made for a boy just his size, sitting on the workshop floor.

ICARUS: (excitedly) This is going to be great!

DAEDALUS: But first a test.

NARRATOR: They made their way to the cliff-side, where the breeze was blowing swiftly out to the sea.

DAEDALUS: I will need the up-draft of a fall from the cliff. If I fail, Icarus, never forget your old father.

NARRATOR: The boy nodded. Daedalus paced backward from the cliff’s edge, gauging the distance carefully. Then with great speed, he ran toward the precipice. When he reached the edge, he jumped forward—out onto the breeze—and plummeted out of sight.

ICARUS: Father!

NARRATOR: The boy ran to the edge, expecting to see his father’s body dashed to pieces on the rocks below.

DAEDALUS: Woo-hoo! Woo-hoo!

NARRATOR: Daedalus swooped up from the waves, soaring on the breeze.

ICARUS: You did it! You really did it!

DAEDALUS: Look at me, Icarus! Look at me!

NARRATOR: He looped up and around, up over Icarus’ head, and with several settling flaps, landed neatly in front of his son.

ICARUS: Me next! Me next!

DAEDALUS: Of course, son! Of course! We’ll leave immediately! No further test is needed. My invention is a success! Wouldn’t it be great to see the look on old Minos’ face when he realizes we have escaped? Ha-ha! He may control the seas, but no man controls the skies!

NARRATOR: Icarus tore back to the workshop and quickly returned with his own miniature set of wings. He began strapping them on.

ICARUS: I can’t wait to fly like you did, father! What was it like?

DAEDALUS: Exhilarating, son! I felt like one of the gods!

NARRATOR: Icarus flapped his own wings for a test and then aimed himself toward the cliff’s edge.

ICARUS: Here I go!

DAEDALUS: Icarus! Wait!

NARRATOR: Daedalus lunged forward and seized the boy’s arm.

DAEDALUS: No! I am an adult, and you are just a boy. Don’t rush ahead foolishly before thinking. What I have just done was a calculated flight! There are things I must tell you first.

ICARUS: Why? I can’t wait to fly!

DAEDALUS: Listen to me! If you fly too close to the ocean’s spray, the water will wet down your feathers. They will grow too heavy, and you will fall into the ocean and drown. If you fly too high, the heat of the sun will melt the wax that holds the wings together. So, please, son, fly a moderate pitch, or you will be in great danger.

ICARUS: No loopty-loops or anything?

DAEDALUS: No.

ICARUS: I’m not stupid. I watched you. I know what to do now.

DAEDALUS: Promise me, Icarus.

ICARUS: (grudgingly) I promise.

NARRATOR: The aged father wrapped his winged arms around his son.

DAEDALUS: Now, let us leave this place for good—before Minos’ guards spot us here. Icarus, you will go first, but don’t fly too far ahead. Head straight north, toward the mainland.

ICARUS: Got it!

NARRATOR: The youth bolted toward the cliff’s edge, wings spread. As soon as he had disappeared over the side, Daedalus began his own take-off.

Soon father and son were soaring on the salty sea breeze.

ICARUS: Father! This is greater than I ever imagined! Look at this!

NARRATOR: The boy twirled about in the sky.

DAEDALUS: Icarus, be careful! This isn’t a game! You promised!

ICARUS: What? I can’t hear you! Hurry up, father. I’ll beat you there if you’re not careful!

NARRATOR: The old inventor beat his wings furiously to catch up with his son, but Icarus easily outstripped him.

DAEDALUS: (shouting) Icarus! You’re flying too fast—and too high! Icarus!

ICARUS: This is great! This must be how the gods feel!

NARRATOR: Icarus looked back over his shoulder. His father was far below and far behind. Then the boy looked up. The sun was much too close—its heat was bearing down upon him. Sweat was dripping from his brow.

ICARUS: (scared) Father?

NARRATOR: Something hot and sticky was running down both his arms. He flapped them furiously to shake it loose. When he did, feathers flew in all directions. They had come loose. To his horror, Icarus began to fall!

ICARUS: No! Father!

DAEDALUS: (yelling) Icarus!

NARRATOR: Daedalus saw his son spiraling down toward the sea, a trail of feathers in his wake. He turned his head just as Icarus crashed into the brine.

DAEDALUS: (weeping) My son. My son.

NARRATOR: Time and time again, the old man swooped as low as he dared over the spot where his son had fallen, yet he never saw any trace of the boy. Finally he gave up hope and, despairing, continued his flight toward Athens.

Many sailors later reported seeing a large bird in the sky that day, a bird with its head hung low, who only barely saved itself from plunging into the sea when the wind brought it low. They said it had the strangest cry—like a man whose heart was broken.

DISCUSS

DRAW

Draw a diagram of what you believe the Labyrinth looked like.

WRITE

Modernize the story of Daedalus and Icarus.

Minos and the Minotaur

In his time, King Minos was the most powerful king in the regions surrounding Greece. His superior navy, commanded from his island kingdom of Crete, kept the mainland city-states in constant terror. It was rumored that beneath his palace at Knossos there was a baffling maze called the Labyrinth. Through the many corridors and passageways roamed a frightening beast, part-bull, part-man. Those who displeased Minos were dropped into the Labyrinth and made a quick meal for the Minotaur, “The Bull of Minos.” Even though King Minos used the Minotaur as an agent of fear, it was also one of his darkest secrets. When Minos ascended the throne, he begged Poseidon, the sea-god, to give the Cretans a demonstration of divine favor. Poseidon complied and sent a pristinely white bull out of the sea. Minos was to sacrifice the bull back to the sea-god in order to thank him for his blessing. The Cretans had a long history of bull-worship—to them it was a sacred animal—and this bull was the best specimen Minos had ever seen. He simply could not sacrifice it; instead he substituted an inferior bull in its place—hoping that Poseidon would be fooled. The sea-god was not fooled, and in retribution he cursed Minos’ wife, Pasiphaë, with a maddening lust. The object of her lust was none other than the bull from the sea.

About this time Daedalus, an Athenian exile, arrived in Crete and quickly became a court favorite because of his brilliant inventions. Queen Pasiphaë went to the inventor in secret and begged him to devise a way to bring her and her love together. Goaded by the offer of riches, Daedalus designed a cow-like structure that the queen could hide within and through this disguise meet with the bull. This unnatural union produced the Minotaur.

When Minos saw the creature his wife had delivered, he was disgusted. He called Daedalus to him—and rather than punishing the inventor for his part in this sordid affair, commissioned him to build an enormous maze beneath the palace—filled with tricks and traps that could contain the horrific creature. Minos would use the Minotaur to strike fear into the hearts of his enemies.

Wisdom Versus Intelligence

It is easy to look at the story of Icarus and think of how you would do things differently. What kind of idiot blatantly ignores instructions from such a wise father? But do not start casting stones too quickly. Think about your parents. Have you ever disregarded their advice only to later find out they were right? Almost everyone has. Every day, sons and daughters disobey parents who have much more wisdom than they do. This statement might cause you to pause. Are your parents wiser than you are? Yes. Does this mean that they are smarter than you are? Not necessarily. This is because there is a difference between wisdom and intelligence.

Wisdom seems to come with age. There is an etymological (word history) connection between the words wisdom and wizard. The stereotypical wizard is very wise and very old. Wisdom means accumulated learning, and the way that people learn best is by doing. Elderly people have done a lot in their time—each wrinkle and gray hair exists for a reason. They have lived life; they have made their mistakes, and even though the bruises have faded, the lessons learned remain.

Intelligence is the ability to learn and reason. But most of the time, you cannot learn something from a situation until you have gone through it. Adults telling children that the stove is hot will not keep them from touching it. Children will have to touch it themselves before they know it is hot. No pain, no gain. Or to change up the words, know pain, know gain. Human experience is one of the best teachers around, and even though not all lesson are painful ones, some are learned in such a hard way that there is no second chance. Life isn’t a video game. There’s no Reset or Redo button. Game over.

Everyone has had an “Icarus moment,” where parental directions were ignored and things went badly. If you are reading this, you might have experienced yours and lived to tell about it. The myth of Icarus is a serious one: Young people are not immortal, no matter how much they feel so. The world is a dangerous place, and wisdom teaches that. Sometimes it is a lesson learned the hard way.

Most young adults find it hard to listen to their parents. Yet as they grow older (and give life a shot on their own), they realize that their parents were actually smarter than they thought. They realize that their parents’ wisdom is not an insult of their own intelligence. In a Ken Burns (2002) documentary, Mark Twain put it this way: “When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much he had learned in 7 years.” Even though he is being humorous, Twain realized that it was he who had done the learning, not his father. He had gotten older and wiser.

DISCUSS

Myths as Warnings

One function of myths in ancient societies was to act as warnings. Some tales came with what we would call the “moral of the story.” Even though these morals were unstated, they were outlined clearly enough in the story for the listener to catch on. More often than not, myths warned of hubris, or pride. Other myths warned against the minor and major taboos of Greek society: incest, murder, rude conduct in the home of a host, neglecting the burial of a dead body, and bestiality. The myth of Minos gives us two warnings: First, do not disregard the edicts of the gods, or your wife will lust after a bull. Secondly, do not engage in bestiality, or your son will be half-man, half-bull. It seems somewhat silly to us now, but these warnings were an integral part in the formation of the myths.

In this story, Icarus’ act of hubris was comparing himself to the gods—a comparison that always brings plenty of pain to those who make it. He’s also incredibly careless. Not only does he completely disregard his father’s instructions, but he also ignores the danger of his situation—placing himself above mortal consequences. It is only when the wax is dripping down his arms that he realizes that he is doomed. Up until that point, he forgets that he is mortal.

In ancient Rome, when a general returned from battle victorious, an enormous parade was often conducted in his honor. As he rode triumphantly through the adoring crowd with all of Rome shouting his praises, it was his servant’s job, riding in the chariot behind him, to whisper “memento mori” in his master’s ear—“Remember: Thou Art Mortal.” This served as reminder to the general, in spite of his enormous success, to not place himself on the level of the gods. Today, Fortune may be smiling on him. Tomorrow, maybe not.

Mythology is filled with characters who get a little too full of themselves and rashly compare themselves to the gods. The gods, not taking this lightly, appear and remind these characters of the pecking order—destroying or transforming them in a flash of divine fury.

In Detail: The Fall of Icarus

The Roman poet Ovid, renowned for his dramatic storytelling ability, provides us with the best account of Icarus’ fall.

And as a bird who drifts down from her nest

Instructs her young to follow her in flight,

So Daedalus flapped wings to guide his son.

Far off, below them, some stray fisherman,

Attention startled from his bending rod,

Or a bland shepherd resting on his crook,

Or a dazed farmer leaning on his plough,

Glanced up to see the pair float through the sky.

And, taking them for gods, stood still in wonder. . . .

By this time Icarus began to feel the joy

Of beating wings in air and steered his course

Beyond the father’s lead: all the wide sky

Was there to tempt him as he steered toward heaven.

Meanwhile the heat of sun struck at his back

And where his wings were joined, sweet-smelling fluid

Ran hot that once was wax. His naked arms

Whirled into wind; his lips, still calling out

His father’s name, were gulfed in the dark sea.

And the unlucky man, no longer father,

Cried, “Icarus, where are you, Icarus,

Where are you hiding, Icarus, from me?”

Then as he called again, his eyes discovered

The boy’s torn wings washed on the climbing waves.

He damned his art, his wretched cleverness,

Rescued the body and placed it in a tomb,

And where it lies the land’s called Icarus.

As Daedalus put his ill-starred son to earth,

A talking partridge in a swamp near by

Glanced up at him and with a cheerful noise

The creature clapped its wings. And this moment

The partridge was a new bird come to earth—

And a reminder, Daedalus, of crime. (Ovid, 8/1958, p. 205)

Immediately after his description of Icarus’ fall, Ovid segues into his next story—a dark tale from Daedalus’ past.

The Inventor’s Apprentice

Long before Daedalus made his journey across the sea to Crete, he gained fame in Athens as an inventor. It is said that Daedalus was the first to invent the tools of carpentry and with them created statues that walked as humans do. His workshop was on the Acropolis, the high hill of Athens, and when his reputation was cemented, his sister sent her son, Perdix, to be apprenticed to him. She hoped Daedalus’ genius would rub off on the boy; after all, Perdix had always dreamed of being an inventor. Daedalus grudgingly agreed, as long as the boy did not get in the way. He tried to ignore the boy as much as possible, giving him menial tasks like running to the marketplace, boiling water, and stoking the fires.

One day Daedalus and Perdix were visiting the Athenian seashore, and Perdix discovered the skeleton of a fish half-buried in the sand. He excitedly showed his find to his uncle, who grumbled and shooed the boy away. An idea had awoken in Perdix’s mind. Watching his uncle work had sharpened his own ingenuity, and within the spine and ribs of the fish, he saw his first invention. Because Daedalus barely acknowledged his existence, it was not hard for the boy to hide his project from his uncle. Perdix patterned the shape of the fish’s ribs in a sheet of tin and attached a makeshift handle to one end. When he pulled the invention across a wooden surface, the metal teeth dug in. He had invented the first saw.

Eventually, Perdix caught Daedalus’ attention long enough to unveil his inventions. Not only had the boy made a saw, but also a compass for drawing perfect circles. Daedalus was flabbergasted. Here was a boy he had passed off as a complete imbecile showing him the most perfect inventions he had ever seen. Along with astonishment, something else was hiding in Daedalus’ heart: He feared that the genius of this boy would match or even surpass his, that Perdix’s inventions would become world-famous instead of his own. Barely knowing what he was doing, Daedalus grabbed the boy and, despite his pleas for mercy, hurled him out the high window of the workshop. Many in the streets below looked up as they heard the commotion and saw the young boy falling to his death and Daedalus’ shadowy figure in the window. An outraged mob of witnesses stormed the workshop and dragged Daedalus before the king. Because Daedalus had done so much for Athens, the king did not execute Daedalus but banished him from Athens forever.

Those who went to search for the body of the boy could find no trace of it. It had disappeared. In fact, the goddess Athena had transformed the boy as he fell into a new type of bird, the perdix. According to the Greeks, the perdix remembers its fall from the high Acropolis, and because of this, never builds a high nest like other birds; it is completely content to stay safe and sound on the ground. In English, the perdix is called the partridge.

DISCUSS

Unearthing the Palace of Minos

When British archeologist Sir Arthur Evans unearthed the remains of a Bronze Age palace on the island of Crete, it was quickly associated with the legendary King Minos. Evans named the culture that he discovered Minoan after Minos. The site became known as “the palace of Knossos,” and the ruins discovered there reflect the ancient legend of the Labyrinth. In fact, the term palace gives off a false impression, for it’s not a single structure built as the home of royalty, but a tight cluster of interconnected buildings that served a variety of purposes and housed people from every level of society. Of the hundreds of rooms, some are very obviously royal quarters, some appear to be workshops, and some were designed for religious practices. The layout of the “palace”—many rooms connected by narrow hallways that curve sharply and intersect with one other in a way that confuses a logical sense of direction—probably gave rise to the Labyrinth legend. The term labyrinth is a Minoan, not Greek, word meaning “place of the double-axe.” Some believe that the double-axe (or battle axe, as some might call it) was used in Minoan sacrifices.

One of the most amazing discoveries was the artwork of the palace, which gives even more insight into the culture. Frescoes decorate the passageway walls (which have a disorienting effect on those who pass through them). These paintings show a society devoted to the divinity of the bull—as the Minos legend suggests. The most famous image shows three youths performing a sacred bull-jumping ceremony. In the painting, a young girl holds the horns of a large bull as a youth leaps nimbly across its back, and another young girl waits behind to assist with his landing. It is believed that acrobatic, bull-jumping feats such as this one (kind of an ancient rodeo) were common entertainment on Crete. Other paintings depict a man (probably a priest) wearing a bull’s mask, an image that could have inspired the Minotaur myth. Some speculate this was the king or a priest enacting a ritual as the divine bull-god. (Ceremonies performed in this way could have given rise to the myth of Pasiphaë and the bull.) One of the most splendid artifacts is a vessel shaped like the head and horns of a black bull used for the pouring of libations (liquid sacrifices).

At some point the Minoan civilization was destroyed (possibly by a volcanic eruption) and the Minoan kings lost the power they had over the sea. Later Athens would arise as one of the greatest naval powers in the Mediterranean. The fall of Crete and the rise of Athens is reflected in the myth of Theseus’ defeat of the Minotaur, and like most others, this myth contains the echoes of historical truth.

Landscape With the Fall of Icarus, by Pieter Breughel the Elder, 1558

Paintings, Poems, and Progressive Rock

Throughout the centuries, artists have tried to capture the Fall of Icarus in various media, using the subject matter of Icarus to comment on youthful impetuousness and the brevity of life. For this activity you will analyze three types of media: artwork, poetry, and song.

Go to the Web Gallery of Art (http://www.wga.hu) and analyze the following paintings: “Landscape With the Fall of Icarus” by Hans Bol (1534–1593) and “Landscape With the Fall of Icarus” (c. 1588) by Pieter Brueghel the Elder. Although the paintings have the same title and originate from the same time period, they have different themes. What is the difference between the two paintings?

Now read an excerpt from a poem by the Anglo-American poet W. H. Auden (1907–1973), “Musee des Beaux Arts,” which comments on “Landscape With the Fall of Icarus” by Brueghel:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters; how well, they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

. . .

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on. (Auden, 1938/1979, lines 1–4, 14–21)

DISCUSS

Finally, listen to the song “Dust in the Wind” by the band Kansas. Connect the theme of the song to both the painting by Brueghel and the poem by Auden.

DISCUSS

Theseus and the Minotaur

The Athenian hero Theseus is the warrior who finally put an end to Minos’ monster. Theseus grew up unaware that he was actually the son of a king. His mother showed him an enormous boulder and told him that the secret to his father’s identity lay beneath it. When he was strong enough to move the boulder, she would tell him who his father was. Theseus trained throughout his teenage years, and at the age of 16, he at last lifted the boulder. Beneath it were a pair of old sandals and a well-crafted sword. These, his mother told him, belonged to his father, Aegeus, the King of Athens. Theseus at once set off to be reunited with his father at Athens.

When Theseus arrived, he found Athens in the midst of a dark time. Every 9 years, the Athenians were forced to select from their children seven boys and seven girls to send to Crete—sacrifices to King Minos and his Minotaur. The next round of sacrifices was due, and the king was powerless to stop it. There was also a rumor that the woman whom he had recently married was actually a witch. Theseus gained entrance to the palace, but kept his true identity a secret.

The new queen was, in fact, the witch Medea, who had fled to Athens after murdering the king and princess of Corinth. She invited Theseus to a banquet, and because she had divined that he was actually Aegeus’ son, convinced the old king that Theseus must be an agent of his enemies. Aegeus offered Theseus a poisoned drink, but when Theseus rose to propose a toast, he recognized the boy’s sword as his own. He knocked the drink from Theseus’ hands and banished Medea for trying to murder his true son.

The reunion between father and son did not last for long. Theseus declared that he felt it his mission to go with the sacrificial youths to Crete and put a stop to this grisly tribute. Aegeus reluctantly agreed, but he begged Theseus to let him know from afar if he was successful. The ship that carried the sacrifices would leave Athens with black sails. If he returned alive, Aegeus pleaded, Theseus should change the sails to white so that Aegeus could know his son’s fate from far off. Theseus agreed.

Theseus was let in among the sacrifices and journeyed along with them to Crete. When the prisoners were brought into the court of King Minos, Theseus confronted the king bravely. King Minos’ daughter, Ariadne, saw Theseus’ bravery and fell in love with the handsome Athenian. That night—the night before the prisoners would be fed to the Minotaur—she met Theseus in his cell and promised to help him kill the beast if he would promise to take her back to Athens and make her his wife. Theseus agreed.

Daedalus had told Ariadne the secrets of the Labyrinth. She, in turn, told these to Theseus. She gave him a sword and—in one version of the story—a magical crown of light to guide his path. She tied one end of a spool of string to the entrance of the Labyrinth and gave the Theseus the other end. Using this he could find his way back after killing the Minotaur. Theseus thanked her for her help and disappeared into the depths of the maze.

In the middle of the Labyrinth, Theseus wrestled with the Minotaur and slew it. In some stories he did this with his sword. In others, he killed the creature with his bare hands. He returned to Ariadne, they freed the other prisoners, and sailed away from Crete under the cover of night, but not before drilling holes in the hulls of Minos’ fastest ships. Along the way the crew stopped on the island of Naxos for a rest, and while Ariadne slept in the shade, Theseus ordered everyone back on the boat. He left the girl who had saved him alone on an island to die. When at last the cliffs of Athens came into sight, Theseus saw his father standing on the heights—watching for his son to come back to him. To his horror he saw his father jump forward and fall the length of the cliffs. Then he remembered: He had forgotten to change his sails from black to white.

DISCUSS

MYTH-WORD

The sea where Aegeus jumped to his death is called the Aegean Sea today because of this myth.

Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC): A Real-Life Daedalus

The writers of Greek mythology imagined Daedalus as an inventor whose abilities could never be rivaled—a visionary who could think a thing and then bring it into existence. In many ways, Daedalus is similar to a real-life Greek, one who lived in the city of Syracuse on the island of Sicily, and had a similar relationship to its king as Daedalus had to Minos. Just as King Minos commissioned Daedalus to build the Labyrinth, the King of Syracuse put the brilliant mind of the inventor Archimedes to work.

Archimedes was first and foremost a mathematician. He successfully calculated the geometrical relationship between a sphere placed inside a cylinder of the same height and width: The sphere has 2/3 the volume and surface area of the cylinder. He also calculated the relationship between the diameter of a circle and its circumference, also known as π.

In a famous story, the King of Syracuse approached Archimedes with a problem: The king had commissioned a solid gold crown to be made, but he suspected that the crown-maker had used a combination of silver and gold in order to cheat him. After the king asked Archimedes to prove that the crown was not solid gold, the mathematician was perplexed. How could he prove such a thing without actually destroying the crown? Later when Archimedes was climbing into his brimming bath, he noticed how the addition of his body to the water caused it to overflow. He immediately knew how he could prove whether the crown was solid gold. He jumped out of his bath and, running naked through the streets of Syracuse, shouted, “Eureka! Eureka!”—which in Greek means “I have found it!” He ran all the way to the king to tell him that he could determine if the crown was solid gold without destroying it. By placing it in water and measuring the amount of water displaced, and then repeating the experiment with a block of gold that equaled the amount given to the craftsman in order to make the crown, Archimedes determined that because the density of the crown was indeed lighter than the amount of gold, the crown was not solid gold.

In another story, the mathematician impressed the king by rigging a fully loaded, three-masted ship up to a series of pulleys. Then, with only the small effort of working the controls, Archimedes was able to raise the ship and move it along the land just as if it were sailing on the sea. Archimedes boasted, “Give me a place to stand on, and I will move the Earth” (Anderson & Stephenson, 1999, p. 42). Upon seeing this, the king marveled at it and begged Archimedes to design battle engines that could defend the seaside city from invaders. The inventor honored this request. Although Archimedes invented “peaceful” inventions such as the screw pump (or the Archimedes Screw—a spiral within a cylinder that can elevate water from one level to another for irrigation), the majority of his recorded inventions were created for warfare.

When the mighty Roman military decided to crush Syracuse by sea, they learned the hard way how one brilliant mind can pose an incredible obstacle. Archimedes invented huge catapults and stone-throwers that were accurate enough to sink many Roman ships from a great distance. When the surviving ships had made it close enough to be out of the range of the larger weapons, Archimedes unveiled a series of smaller catapults and stone-throwers—perfect for closer distances—and continued to sink ships. Some Roman ships oared close to the city cliffs and began to erect ladders in order to scale them. This only gave Archimedes occasion to show the attackers his next deadly invention: a crane that swung out over the cliff-walls, dropping a metal claw that clamped down on the bows of the ships. When the ropes attached to the claw began to retract, the cranes pulled the ships up into mid-air. The soldiers on the ships clung on for dear life, as the claws dashed their vessels back into the water. Some accounts of this battle even say that Archimedes invented a heat-ray—a series of mirrors that was able to focus the sun’s rays on approaching ships to such an intensity that they burst into flames. Whether or not the heat-ray was actually true (or just a colorful addition as most historians think), the war engines of Archimedes effectively demonstrated mind over matter.

The Romans had the last laugh. Because their sea attack had been completely obliterated by Archimedes’ arsenal of deadly gadgets, they decided to surround the city, blockade its port, and starve its citizens into submission. When at last the Romans made a successful offensive against the besieged city, a Roman soldier found Archimedes squatting in the road. The old mathematician was muttering to himself while he drew a diagram in the dirt. The soldier ordered him to surrender and come along quietly. When Archimedes refused, the soldier killed him on the spot. “Do not disturb my circles!” are often said to have been Archimedes’ last words.

DISCUSS

ANALYZE

Who are some of the other great inventors of history? What personal characteristics helped develop their innovative spirit? What purpose do inventors serve in society?

FUN FACT

Historians noted that Archimedes worked so intensely that he sometimes forgot to eat, sleep, or bathe. Now that is a workaholic.