CHAPTER 9

Fathers and Sons

SEARCHING FOR ODYSSEUS

Cast Telemachus Son of Odysseus, prince of Ithaca Penelope Wife of Odysseus Antinous Suitor to Penelope Eurymachus Suitor to Penelope Menelaus King of Sparta |

Odysseus Famous adventurer Helen Queen of Sparta Athena Goddess of wisdom Nestor Wise old king of Pylos Pisistratus Son of Nestor |

NARRATOR: I am Telemachus. These days all of the bards have their favorite song—a song about a man who spent 10 years at sea, trying to get home. I’m mentioned in the song. I have quite a big part in it actually. But the true star is Odysseus, as always.

People have always said to me, It must be amazing to have a father like Odysseus! They, of course, are talking about his amazing adventures. They know nothing of the man himself. And for much of my life, the man was even a mystery to me.

Odysseus left for the Great War at Troy long before I was old enough to remember him. My mother said he wasn’t a tall man. She said that he wasn’t the strongest or the fastest, but he was clever. I remember she used to say:

PENELOPE: Telemachus, my son, if there is a man who could find his way home from Troy, it is your father. Athena has always loved his crafty mind. She will guide him home safely.

NARRATOR: Growing up, this gave me hope, and when I was 10 years old, the first news of Greek victory reached us. Troy had fallen. The united kings of Greece had won the war. Odysseus would soon return, or so we thought. But as the tides brought many ships home filled with fathers—none came for me.

PENELOPE: Continue to watch the seas, Telemachus. Above all things, your father is faithful.

NARRATOR: As weeks turned into months and yawned into years, I guess my innocence melted away. I had to face facts. Despite what mother said, Odysseus wasn’t coming home, and it would be me—only me—in charge of our island kingdom, Ithaca. Mother never showed despair in front of me, though I could see it there in the rims of her eyes.

PENELOPE: Telemachus, I worry about you, my son. Why do you not make friends? Why do you not chase the girls as other boys do? Drink deep. These are your carefree days.

TELEMACHUS: We must face realities, Mother. Odysseus is not coming home.

PENELOPE: Telemachus! He is father to you.

TELEMACHUS: Father? I never even knew the man. He is a stranger to me.

PENELOPE: He knows you, Telemachus. He will return to us—no matter what. He is faithful. He is faithful.

TELEMACHUS: Are you telling me that? Or yourself?

NARRATOR: A distraction from our long wait of grief came soon enough. Vultures descended. A herd of young nobles from the surrounding islands—108 to be exact—came knocking on our door. They were suitors for my mother’s hand, but only in name. They only lusted for the crown she represented.

ANTINOUS: Odysseus is dead, my lady! It is time you marry again.

PENELOPE: Not dead, good sir. Only delayed. Because my husband is still living, I cannot remarry. But I welcome you to await his return here at Ithaca in our humble halls.

NARRATOR: The suitors smiled at my mother’s polite offer. So they moved into our halls, eating our food, killing our livestock, guzzling our wine, and romancing our serving wenches. It wouldn’t take long for delicate Queen Penelope to break, snap under the pressure of rudeness. They were rough men. They were cruel men. They were pigs. Mother was a woman. I was just a boy. We were at their mercy. Years came and went. I was 17 . . . then 18 . . . then 19. Even though the suitors made a game of depleting our resources, they tired of mother’s tricks and refusals. But even though she managed to evade their advances, each day without Odysseus eroded away a bit of her resolve, like a wave impacting upon the beach.

ANTINOUS: The King of Ithaca is dead! Choose a new king from among us!

NARRATOR: I was nearing manhood. The suitors knew, as the rightful heir, I was growing dangerous. This was their last offer of “peace” before they risked open war. Mother saw this as well.

PENELOPE: I will choose . . .

EURYMACHUS: Yes! Finally!

PENELOPE: (continuing) As soon as I have woven a shroud for my father-in-law, Laertes.

EURYMACHUS: What?

PENELOPE: The years lie heavily upon him. I must finish his shroud before death reaches him. Surely you understand.

NARRATOR: How could they understand? They were practically barbarians.

ANTINOUS: (shrewdly) Fine! Let her weave for the old coot. How long could it take?

EURYMACHUS: Hopefully not longer than the wine holds out! (laugh)

NARRATOR: This would be her final diversion. Her last-ditch evasion. Mother took to her loom. In her weaving, she put the image of the sea, and Odysseus’ ship tossed upon it. Even in all her despair, a thread of hope still survived.

I could not explain it, and I know it must have been some trick, but though she sewed for the span of each day, her tapestry was never completed. Each morning there was more work to be done, and the suitors’ ambitions were thwarted for yet another day.

TELEMACHUS: Mother! What will happen when your weaving is completed? Will you really marry one of those

. . . those . . . pigs?

PENELOPE: To keep you safe, my son, I would do anything. But your father will return first though. I feel it.

TELEMACHUS: I cannot stand it. These men eat up our food, drink up our wine, and lie with our women. They have turned our noble home into a brothel. We still have friends in our own household, don’t we? Let me drive these suitors from our home!

PENELOPE: Friends? Telemachus, we have no friends. Only a few here at Ithaca remain loyal to us. All of the others have been bribed or frightened into corruption.

TELEMACHUS: Then I will go to get help elsewhere!

PENELOPE: Yes, go! But if you go, do not return. Do not return until your father has come home and made Ithaca safe again.

NARRATOR: I intended to leave and return with an army. Odysseus had many friends among the other kings of Greece. Surely there would be one who would help me. But a goddess found me first.

An old sailor came to our hall, his head bare and his beard a grizzled mess. His skin was burnt and swollen by endless hours beneath the sun. That was his outward appearance at least. His eyes were gray. How many sailors have you seen with gray eyes? I knew it was Athena at once.

Those who later told the story said that Telemachus had no idea he was in the presence of a goddess. Odysseus could always see through her disguises, but Telemachus—dumb Telemachus—never the match of Odysseus—was completely fooled. I allowed Athena to play her little trick.

ATHENA: (old man voice) Young man. I am an old sailor, Mentes, a friend of Lord Odysseus for many years. I seek the hospitality of your hall.

NARRATOR: The gods always think they’re so clever—poking their noses into everyone’s business.

TELEMACHUS: You come at the wrong time, old man. This hall has given all the hospitality it can. My mother, the queen Penelope, has been made a prisoner in her own home.

NARRATOR: I filled “Mentes the sailor” in on the entire situation—how the suitors had crawled out of every surrounding hole-in-the-wall island and converged on Ithaca. It was all a farce, really. Here was a teenage boy telling information that his listener already knew to a goddess acting out a disguise that the boy had immediately seen through. We were both playing our respective parts.

ATHENA: (angrily) I’ve known Odysseus forever! He wouldn’t dare stand for this!

TELEMACHUS: Odysseus is not here, old man. His bones lie out in the waves somewhere, I imagine.

ATHENA: (strangely) No! No! I know that he is alive. It must be some prophecy that the gods have placed in my brain, but I know that he is alive. Someone—or something—holds him captive across the wine-dark sea. But he will return.

NARRATOR: I stared into her gray goddess eyes.

TELEMACHUS: If you say so, my friend, then I will believe it.

ATHENA: (happily) So you are Telemachus! My, how you have grown! I see much of your father in you.

TELEMACHUS: (bitter laugh) Mother has always told me that Odysseus was my father. But who in this world ever truly knows who gives him life? My friends call me lucky—to be the son of such a famous father. I say the lucky ones are those who see their fathers grow old in the midst of their possessions. I must be the most unlucky son who ever lived.

NARRATOR: It was then that something in her voice changed. Even a fool could have heard the difference.

ATHENA: (angrily) Unlucky? Whose blood flows through your veins? Your father would not give up so easily, Telemachus! You are no longer a whining boy! You’re a man! Send these suitors packing! Gather them together and command them to leave!

TELEMACHUS: They will only refuse. I know it.

ATHENA: Of course they will, but they will also see how close you are to becoming a man—a dangerous man. Then, after you have delivered your message, take a crew of trusted sailors and seek elsewhere for news of your father.

TELEMACHUS: Just leave my mother behind?

ATHENA: Yes, Telemachus.

TELEMACHUS: Where should I go?

ATHENA: At Pylos seek out King Nestor. He was one of your father’s greatest friends. Then travel to Sparta and speak with King Menelaus. Between the two of them, you just might hear word of your storm-tossed father.

TELEMACHUS: (shrewdly) Tell me, sailor, what gives you such clairvoyance?

NARRATOR: The gray eyes flashed, and the shape of the sailor melted away. The goddess winged herself away, transformed into a high-flying owl.

TELEMACHUS: (laughs) The gods are definitely a dramatic lot.

NARRATOR: The bards always say that at this point, I was beside myself with wonder. I had been in the presence of a goddess all along! Stupid Telemachus.

I returned to the common hall, where the suitors had set up their never-ending feast. It stunk like overspiced food, unmixed wine, and sex—the three vices of men.

TELEMACHUS: (angrily) Suitors! Neighbors! Men of the surrounding isles! I am Telemachus, the son of Odysseus, ruler of Ithaca.

NARRATOR: The drunken slobs turned. Some hung limply in the arms of the serving wenches. Some disrespectfully continued their feasting.

TELEMACHUS: Too long have you haunted my mother's hall. I command that you leave this palace. Surely Odysseus is dead, but I am his heir, and Ithaca is mine.

NARRATOR: The two ringleaders, a couple of boars called Antinous and Eurymachus, began to howl with laughter.

EURYMACHUS: (drunkenly) And if we don’t, what’s a limp-wristed creampuff like you going to do about it?

ANTINOUS: (fake respect) We follow the will of the gods, boy! You have no authority here!

EURYMACHUS: Yeah! (hiccup)

TELEMACHUS: (violently) The gods? For your rudeness here, I pray that the gods strike you down!

NARRATOR: This sobered them a bit. They had never seen such strong words from me.

TELEMACHUS: My mother is an honorable woman, and you—

ANTINOUS: (growling) Your mother is a harlot, boy! A deceiver! Don’t you know what’s she’s been up to?

EURYMACHUS: (yelling) Tricked us! Tricked us all!

(shouts of approval from the suitors)

ANTINOUS: Silence! She’s had no intention of completing that shroud she’s been weaving. Every night she’s been pulling loose her day’s work.

EURYMACHUS: The lying wench!

ANTINOUS: Learn to hold your wine! (to Telemachus) Her very own maids ratted her out. Even they were appalled by her deceit.

NARRATOR: That was a laugh. The maids of Ithaca had become more like prostitutes.

ANTINOUS: Now she’s caught! And she will marry one of us. Her excuses are done.

NARRATOR: I could only sneer as they returned to their revelry.

My part had been played. I had taken my stand and proved powerless. It was time to begin my journey.

Old Eurycleia, my nurse and Odysseus’ nurse before me, was the only one I told of my plan. She poured unmixed wine into jars and sewed up bags of barley for my voyage and kissed me upon the forehead before I left.

By the sea, a ship and crew was already waiting (Athena’s doing, I later discovered) and standing nobly beside the beached vessel was Mentor, Odysseus’ righthand man. When Odysseus had left for Troy, he placed Mentor in charge of Ithaca and, consequently, in charge of me. There stood Mentor now to be my guide.

Or so it seemed. Once again, it was not quite Mentor. His sea-gray eyes gave him away.

ATHENA: (man voice) Few sons are the equals of their fathers. Many fall short. Too few surpass them. But in you, Telemachus, I see Odysseus’ cunning.

NARRATOR: And so we took to sea, Athena-Mentor at my side. We steered a course toward Pylos, home of Nestor, oldest and wisest king of Greece.

I thought of Odysseus. If what Athena had said was true, what force could be powerful enough to keep him away from his family and his home? Or perhaps we only thought that he wanted to be home. Perhaps he preferred the adventure of the open sea to home and hearth.

We found Nestor in his palace, and I thought he must be one of the deathless gods. The man had reigned over his people for three generations of men and still his eyes blazed with youthful glory. A banquet was in progress, and he welcomed us to it, even without formal introductions.

ATHENA: (whispering) When the time is right, Telemachus, ask of Nestor your question. Remember: He is far too wise to lie.

TELEMACHUS: (whispering) What should I say? I’ve never spoken in front of a king!

ATHENA: Your father would find the words. You must do the same.

TELEMACHUS: But I’m not Odysseus. Why does everyone keep assuming . . . ?

NESTOR: (addressing Telemachus) Tell me, young traveler, what brings you to sandy Pylos?

NARRATOR: I rose, practically shaking with terror.

TELEMACHUS: (grandly) Noble Nestor, I have heard many tales of your wisdom—a man who has lorded over many men. I see in this hall many of your noble sons. I’m sure your heart swells with pride when you behold them. I have come to your hall seeking not a son, but a father, Odysseus—I believe you know him well.

NARRATOR: The old king stared at me, impressed.

NESTOR: Never before have I heard a young man speak in such a way! So much grace! I believe I see your father in you, my boy. I see his majesty—his majestic demeanor. Are you not the son of Odysseus?

TELEMACHUS: You have guessed it, my lord.

NARRATOR: I told Nestor of the suitors and the plight of my mother. He fumed with indignation, yet when the conversation turned to Odysseus, he could offer me little news.

NESTOR: Odysseus was one of my dearest friends. After the fall of Troy, the Greek kings departed those shores in separate groups. One left swiftly behind the flagship of Menelaus, while the other tarried behind with Agamemnon. I was in the first group, and the last I saw of your father was on the beaches of Troy.

TELEMACHUS: Can you tell me no more?

NESTOR: King Menelaus is whom you should seek. Perhaps he has heard more news than I.

TELEMACHUS: But you said he left the same time as you.

NESTOR: He did, but we were foolish to depart without the blessing of the gods! So hasty were we to return home with the spoils of Troy! In anger, the gods cursed Menelaus. He wandered a full 7 years upon the sea with his golden bride. Agamemnon, who stayed behind to make all of the proper sacrifices, received a swift trip home to Mycenae. Unfortunately, only death waited for him there.

TELEMACHUS: Agamemnon is dead?

NESTOR: Struck down by his wife’s lover. I thought all of Greece had heard of the murder of its greatest king. Queen Clytemnestra took Agamemnon’s cousin Aegisthus into her bed shortly after her husband’s departure, and together they hatched a plan to seize his throne.

TELEMACHUS: What would drive a wife to do such a thing?

ATHENA: The murder of a loving daughter.

NESTOR: Your friend speaks truth. With Menelaus lost at sea, it fell to Orestes, son of Agamemnon, to avenge his father’s murder. He did so. He put the lover and his very own mother to the sword. It took determination! You, my boy, should strive to be such a son!

NARRATOR: The old man’s eyes became soft.

NESTOR: I remember your father before the Great War. I’ve never seen a man more content. He loved his Ithaca and his Penelope. I remember him holding you lovingly in his arms before he left—vowing to return. If any man would wish to return home, it would be he. I hope he still lives.

NARRATOR: Though I did not will them, tears beaded in the corners of my eyes. I wiped them angrily away.

ATHENA: (grandly) Then the course is clear: Go to Menelaus, Telemachus. He will give you the information you seek. Farewell!

NARRATOR: The gray-eyed Mentor rose, and his robe melted into a covering of feathers. Athena once again winged herself away—to the shock of all present.

NESTOR: (in shock) By the gods! My boy! You are truly favored to have a goddess as your companion!

NARRATOR: Nestor and his sons stared at one another in shock over Athena’s circus trick. The bards say that even the second time, I fell for Athena’s disguise. Stupid, gullible Telemachus.

NESTOR: (laughing) Even with my long years, I have never seen such a sight! Telemachus, tonight you will sleep here at the palace. Tomorrow I will have my son Pisistratus take you by chariot to Sparta. (laughing to himself) By the gods! What a night!

NARRATOR: Pisistratus was a nice enough fellow—the kind of young man who gains his identity from his heritage. He wanted to know everything about Odysseus. What first gave him the idea for the Trojan Horse? How did he cultivate such an enormous intellect? What would it be like to have the bards sing of you in your own lifetime?

I spent most of our chariot ride from Pylos to Sparta silent. How did I know? I honestly had no answers for him. He was asking the wrong person.

As Nestor’s palace at Pylos had dwarfed the hall of Ithaca, Lacedaemon, the fortress of Menelaus, dwarfed the latter. Crowds of people thronged through the streets. (cheering of a crowd) Pisistratus stated the obvious:

PISISTRATUS: Must be some kind of celebration.

NARRATOR: We were admitted to the palace, where an enormous feast was being held. Because of our noble bearing and some haughty words from Pisistratus, we were admitted into the royal banquet hall without question. There I beheld the red-haired king himself, Menelaus.

MENELAUS: (happily) What splendid young men! The guards told me two boys had arrived who looked like the gods themselves! I must say they weren’t exaggerating!

PISISTRATUS: What is this happy occasion?

MENELAUS: (laughing) Today, my daughter has been wed! Have a seat! Feast with us!

NARRATOR: He whisked us to a seat among the revelers, promising to soon return. He was beside himself with duties on such a special day.

PISISTRATUS: Father told me of this marriage. Hermione, the daughter of Menelaus and Helen, was given to Pyrrhus, the son of Achilles. A good match, I say.

TELEMACHUS: Any daughter of Helen must be a jewel among women.

PISISTRATUS: I saw her once. She’s fair enough, I guess. Father will make a better match for me—I’m sure of it.

NARRATOR: The noon feast began to give way to the evening feast, and at last Menelaus appeared at their side, winded and somewhat drunk.

MENELAUS: A wedding! There’s nothing like it! Now tell me, lads, where do you hail from?

PISISTRATUS: I am Pisistratus, the son of Nestor, and this is Telemachus, son of . . .

MENELAUS: (in shock) Odysseus! Of course! How did I not see it before?

NARRATOR: Pisistratus looked away in annoyance. Odysseus’ name always seemed to get a bigger reaction.

MENELAUS: Slave, fetch Queen Helen! Clear away these guests. We wish to speak privately with our special guests.

NARRATOR: Menelaus eyed me like a beggar who had found a pearl.

MENELAUS: My boy, what a pleasure! To meet the son of Odysseus! I have never met a finer man!

TELEMACHUS: That is why I have come to you. I hope one day to meet him myself.

MENELAUS: Oh yes. I had my own troubles reaching home, which I shall tell you shortly, but first allow me to introduce my wife. Perhaps you have heard of her? Helen of Sparta.

NARRATOR: As many men claim, after setting eyes on Helen of Troy, or Sparta, or wherever, it is impossible to describe exactly how she looked. Long after our encounter with her, I had to hear Pisistratus stammer over himself trying to describe her features, contradicting himself until he finally resorted to one word: beautiful.

HELEN: Yes, my dear. Helen of Sparta. How nice it sounds! Who are our young guests?

MENELAUS: These are mighty princes, my dear. The son of Nestor and the son of Odysseus.

NARRATOR: Her eyes locked onto mine. There’s a certain feeling you get when you lock eyes with Helen: a kind of worthlessness. You realize how unworthy you are of such a woman. Of course, that just makes you want her all the more.

HELEN: I see that. I remember your father well, my boy. Before the fall of the Troy, he snuck into the city disguised as an old beggar man, scouting out the best way to lay the Greeks’ trap. As the daughter of a god, I could see through his disguise, of course, but I raised no alarm. No, when I saw him and how sharp his mind was—that great Greek mind—I grew homesick. I know what you are thinking: Yes, I, Helen the one who started a war for her own shameless lust. Whore that I am, I missed Greece. Aphrodite’s spell had held me for 10 long years, and its magic at last grew thin. I yearned to sail back home—be reunited with the husband and the daughter I had left behind.

NARRATOR: She took her husband’s hand.

HELEN: Thanks to Odysseus, I saw reason.

MENELAUS: But Odysseus has still not returned to Ithaca, my dear.

HELEN: No? How unfortunate. Did we not hear news of him?

MENELAUS: We did. After we left Troy, Telemachus, the winds of the gods blew us far off course, all the way to the shores of Egypt. There we languished in exile. We knew that some god was holding us there until we repented . . .

HELEN: Tell him of Proteus, dear.

MENELAUS: I was just coming to that, my sweet. Proteus, the Old Man of the Sea, a creature who has the ability to assume the shape of any creature, was rumored to appear on those shores. He—a god himself—would be able to tell us how to return to Sparta.

Not far from where we were moored, Proteus came up out of the belly of the ocean each morning to sun himself upon a rock. I knew in order to get Proteus to tell me what I wished, I must wrestle him. He would change from form to form, trying to loosen my grip. If I held on until the bitter end, I could ask him any question, and he would be forced to answer.

NARRATOR: Menelaus and Helen continued to tell their story like a couple of newlyweds, interrupting and laughing. Who would have thought this was a man and his adulterous wife?

HELEN: (proudly) And so my noble husband hid himself upon the rock, and when the Old Man of the Sea came out of the depths, Menelaus jumped upon him, and the two wrestled fiercely.

MENELAUS: It was no easy contest! He transformed himself into a lion, a serpent, a leopard, and a pig!

PISISTRATUS: (excited) Fantastic!

HELEN: He even assumed the shape of a swift-flowing stream!

MENELAUS: It almost drowned me to hold on!

HELEN: Then Proteus grew into a tall tree! But there was Menelaus clinging fiercely to his highest branches!

MENELAUS: I held on! That was his final form, and his shape-shifting stopped! Then I asked my questions of him. He told me the path to get home, how to make amends with the gods I had offended. I asked after my brother, Agamemnon, and Proteus told me of his death. He also mentioned a Greek king who was lost at sea: your father.

NARRATOR: Finally, the news I had been waiting for.

TELEMACHUS: What did he tell you?

MENELAUS: Proteus said that your father had been a prisoner for many years on the island of Calypso, the sea nymph.

NARRATOR: That night in Menelaus’ palace I fought sleep. All these years, all these waiting years, we had thought Odysseus was dead. But in reality he was the prisoner of a nymph? It seemed too far-fetched to believe. For all his cunning, Odysseus could not escape that? Or maybe he didn’t want to escape. Perhaps he had found a mate he loved more than his Penelope—or even me.

We stayed in Sparta for weeks. Pisistratus loved rubbing elbows with the likes of Menelaus and Helen, but I was restless. Menelaus’ news held little hope for me or my mother.

One morning, I woke, and a gray-eyed woman was standing over me. She wore glistening armor, and an owl perched on her shoulder. Finally, the goddess and I were past disguises.

ATHENA: (booming) Telemachus, return to Ithaca at once. I have beseeched Zeus to free your father. Hermes has gone to the isle of the sea nymph Calypso and commanded her to release him. Your father is on his way home even as we speak.

NARRATOR: Very well, I told myself. I guess I will finally meet this man. This Odysseus. But first some questions for him and his divine helper.

TELEMACHUS: Lady Athena. I openly admit that you are wiser than I, but I must ask why? What was the point of this? This wild-goose chase across the sea? Why didn’t you just tell me what I need to know?

NARRATOR: The goddess smiled sweetly.

ATHENA: Oh, Telemachus. Nothing in this life is ever simple. Your whole life you’ve lived with a space where a father once fit. You’ve tried to fill that space with many things: despair, anger, even hatred. Now your father is coming home. Odysseus is coming home. Don’t you wish to know this noble man whom the mightiest kings of Earth praise? Don’t you wish to know the man who brought Troy to its knees? The man who could make fickle Helen dream of home? Don’t you wish to see the man that other men see in you?

TELEMACHUS: (surprised) I do.

ATHENA: Then your quest is complete. Hurry home. A father is waiting.

NARRATOR: Menelaus offered me passage home, and Athena instructed me not to return to the palace at Ithaca, but to seek out the hut of the swineherd Eumaeus. Eumaeus was always a loyal servant. He smelled a bit, of course, but he was always loyal.

When I found Eumaeus’ dwelling, he had company. Some dirty old man sat in the corner of his hut, running his hands through the pig droppings. Eumaeus was eager to help me, so I sent him on to the palace to tell my mother that I had returned safely.

After he had gone, I experienced yet another miraculous transformation. The old man in the corner seemed to shift, his wrinkles dissipating, his spine straightening, his eyes growing brighter—eyes that some said could resemble mine.

ODYSSEUS: (emotionally) My son!

NARRATOR: I had always wondered what would happen when we finally met. Would we clasp hands? Embrace? Would it be the awkward meeting of two strangers? But it was just the opposite. He held me in his arms—as he had 20 years before—and cried tears of happiness upon my head.

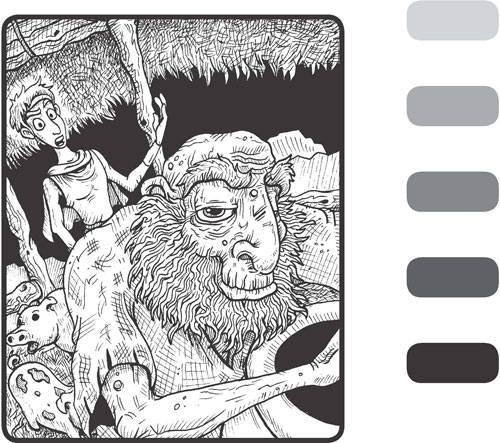

Odysseus and I spent hours talking. He told me of his whole journey: the Cyclops, Scylla, Charybdis, the mystical song of the Sirens that only he had heard. I could only sit there like an enchanted 5-year-old and listen to the amazing story of his voyage.

As he spoke, I was there with him—in Troy, on Circe’s isle, on Calypso’s island, on the very edge of the Underworld.

ODYSSEUS: But tell me of how it goes here, my son. (laughing) My son! How great it is to speak those words!

NARRATOR: I told him of the suitors, of mother’s tricks. When I spoke of her tapestry, his proud smile told me everything. His affairs with Circe and Calypso may have satisfied his body, but never his heart.

ODYSSEUS: There is not a finer woman under the sun than Penelope! Now listen, my son, we must form a plan!

NARRATOR: It was amazing to watch the man’s mind in action. Ten years of wandering had only strengthened his wits. Odysseus would disguise himself as a beggar and make his appearance at the court of Ithaca. I would go to mother, tell her of my quest, but offer her no hope of Odysseus’ return.

ODYSSEUS: Penelope must not know that I live! The shock would be too great for her to conceal!

NARRATOR: With Odysseus hidden within the court, I would remove the weapons from the palace storeroom. Then, when the time was right, we would strike and end the suitors’ lives.

The plan worked perfectly. My return caused quite a stir among the suitors. They were more determined than ever to destroy me. Mother nearly melted when I told her that neither Menelaus nor Nestor offered any hope of Odysseus’ return.

PENELOPE: (weakly) He is faithful.

NARRATOR: Not too long afterward, Odysseus made his entrance. A shaggy shock of hair and a tangled beard covered his face. He’d smeared himself in the dung of swine and hobbled like a hunchback. The suitors instantly made him the butt of their jokes—kicking and jibing at him, forcing him to dance for their merriment. Mother took pity on him, of course.

How strange to see their first glimpse of each other after 20 years! Odysseus didn’t miss a beat and acted his part. Mother never had a clue. A weaker man would have never had such patience, but Odysseus did. The only unexpected twist in our plan came from mother.

PENELOPE: Men of the surrounding isles! Lords who desire my hand! I have reached a decision. Before he left, Odysseus commanded me—in his absence—to select a mate when Telemachus had reached manhood. Because it seems that my husband will never return, I have decided to chose from among you.

NARRATOR: At first I thought she would ruin everything.

PENELOPE: Because I refuse to wed a man who is not the measure of my husband, I will only marry one who can string the bow of Odysseus and shoot an arrow through 12 axe rings.

NARRATOR: Clever mother.

The bow was brought forth—a rough and hardened weapon, nearly inflexible. In all of my days I had never seen it strung. Of course, as with everything to do with Odysseus, there was a trick to it. The 12 axes were driven into the floor, their rings lined up perfectly. The contest was ready.

EURYMACHUS: Back, you dogs! I’ll try it first!

ANTINOUS: I’m next.

NARRATOR: The 108 suitors fell over one another to have their chance. They grunted and tugged until the veins bulged out in their foreheads. Try as they might, none of them could pull the string tight enough to secure it. Even I had my turn. If I proved myself here, there might be an end to the contest. I struggled against the hardened weapon, but it was no use. I was not Odysseus. After all had tried and tired, the cracked voice of the beggar was heard.

ODYSSEUS: (old man voice) I’ll have a try.

(loud jeers and laughing)

NARRATOR: How they howled at him! And I had to chuckle as well. Here was Odysseus’ final trick. As the beggar stepped forward to try the bow, I moved silently and bolted the door to the hall.

EURYMACHUS: (howling with laughter) Look at this fool!

(laughter from the suitors)

NARRATOR: The beggar took the bow into his gnarled hands. He placed one end beneath his foot and began to slowly bend the bow as he pulled the string-loop upward. The suitors stopped laughing.

ODYSSEUS: (regular voice) You see, gentlemen. Things are not always as they appear. You thought that I was an old beggar, but nothing could be further from the truth.

NARRATOR: The beggar—who now looked nothing like a beggar—turned, bow and arrow and man. He took the axe rings into his sights and let the shaft fly. It clipped neatly through all 12 rings.

(gasping from everyone)

NARRATOR: My mother covered her shaking mouth.

ODYSSEUS: Hmmm. Appearances can be deceitful. A fine lesson for any man to learn.

EURYMACHUS: (screaming) It’s Odysseus! Zeus preserve us!

NARRATOR: The next arrow of Odysseus found its mark in Antinous’ throat.

ANTINOUS: (hacking and gurgling)

ODYSSEUS: A lesson, gentlemen—that you will not live long enough to use. (cries of panic)

NARRATOR: I unsheathed my own sword and stepped between the fleeing suitors and the bolted door. And then Odysseus and I slaughtered them—just like pigs.

After the carnage was done, we cleansed the household. Those who had remained faithful to Odysseus were spared. The others found their necks noosed and stretched. The 10 treacherous maids of the household met their fate this way, as well as many devious servants.

When the episode had ended, and Odysseus and mother had wept in each other’s arms, and Eurycleia, the old nurse, had wept over Odysseus and then wept over me, Odysseus turned, placed his firm hand upon my shoulder, and said these words like he’d journeyed 10 years just to say them:

ODYSSEUS: I’m proud of you, my boy.

NARRATOR: I grinned, ear to ear.

TELEMACHUS: Thank you, Father.

DISCUSS

MYTH-WORD

Mentor, the man whose identity Athena takes as she leads Telemachus on his voyage, gives us the term mentor, which we use to mean “a counselor or guide.” The term monitor, which means one who watches, is closely related to mentor as well.

VIEW

View The Odyssey (1997), directed by Andrei Konchalovsky, a television miniseries adaptation of Homer’s poem. What changes have been made to the original story? Do these changes help or hurt the story? Explain.

View the film O, Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000), directed by the Coen brothers. Which episodes from the Odyssey can you pick out in this film?

RESEARCH

ANALYZE

The meaning of Odysseus’ name is connected to a Greek verb that means “to cause suffering.” Some have said Odysseus means “much suffering” or even trouble. How does Odysseus cause suffering or trouble to those he encounters on his journey? How does Odysseus himself suffer on his journey?

Identity

Identity is a theme that runs throughout the Odyssey. Many times Odysseus changes his identity to play a trick. The goddess Athena changes her identity several times to instruct the characters. Telemachus is a young man trying to establish his identity through his father. Odysseus uses a fake identity or name to fool the Cyclops, then foolishly reveals his true identity. Penelope asks Odysseus to prove his identity twice: first by shooting an arrow through 12 axe rings, and then by knowing the secret of the bed they shared 20 years before.

DISCUSS

Fathers and Sons

The Greeks myth-makers understood that the relationship between a father and son is an important one, and the lack of a father figure can affect a person’s destiny. So many sons in Greek mythology are the sons of famous (yet absent) fathers. (More often than not these missing fathers are the gods themselves.) Most of these young men try to fill the void left by their fathers—some seek a reunion with the father, while others journey on a quest to prove (either to their father or themselves) that they truly are their fathers’ sons.

In one myth, a young man named Phaethon has lived his whole life as the son of a single mother. Finally, nearing the brink of manhood, he discovers the true identity of his father: Helios, the god of the sun. Phaethon sets out at once. His destination—the radiant palace at the far end of the world, where Helios, the chariot driver of the sun, comes to rest his fiery horses every night. Phaethon’s quest is to prove once and for all that Helios is truly his father.

Once Phaethon reaches his father’s palace, their reunion starts off well; the god is both proud and overjoyed that his son has sought him out. Even though Helios verifies that Phaethon is indeed his son, the boy is not satisfied. His whole life he has been teased and picked on because of his lack of a father. Now he is desperate to prove that he has one—and an immortal one at that. He asks Helios to grant him any wish. After all, it is the least the god could do after being a deadbeat dad for 18 years. Helios swears by the Styx to honor any request, but is soon horror-stricken at his son’s request. Phaethon asks to drive the chariot of the sun. In spite of his father’s extremely convincing warnings, Phaethon stubbornly refuses to back down, and Helios can do nothing but stand by and let his son destroy himself.

Needless to say, Phaethon’s chariot ride does not go well. The boy is ill-equipped to handle the fiery horses—he is no god—and the team runs amok. First the chariot lunges too high, bumping the stars, and then plummets too low, causing the sea to boil. It swings low over the region of Sahara and reduces its lush vegetation to scorched earth—as it is still. At last Zeus sees that the world will be destroyed if this reckless chariot driver is not stopped. He aims a thunderbolt at Phaethon and lets it fly. We can only wonder what goes through Phaethon’s mind as he plummets down to Earth—blazing like a falling star. Maybe he thinks of his friends, who would definitely believe that he is the son of the sun now. Maybe he is thinking of the shame he brought to his newfound father or the mother he would never see again. Maybe he is only wishing he would have never known his father at all.

Phaethon illustrates a maxim that is spoken by the goddess Athena in the Odyssey. “Few sons are the equals of their fathers,” she says. “Most fall short, all too few surpass them” (Homer, 800 BC/1996, p. 102). She is speaking to Telemachus, the teenage son of Odysseus, who has vowed to go on a search for his father. The young man barely knows who he is looking for. After all, his father left Ithaca for the Trojan War when he was only an infant. What he does know is that he has lived in the man’s shadow his whole life. Like some sons would, he resents being compared to someone he has never met. From an early age, Telemachus has taken on the job of man of the house. His father is missing and presumed dead, his grandfather is nearly mad with grief, and a band of bullying lords have moved into his household and taken over.

All of the other fathers have long ago returned from Troy. It has been years without word from Odysseus. Telemachus’ mother, Penelope, hangs onto the hope that Odysseus has been delayed. But Telemachus is starting to doubt. How can you trust someone you have never met? Telemachus sets out on his own journey—partially to find out news of his father and partially to discover exactly who the man is.

The Telemachiad, the portion of the Odyssey that deals with Telemachus’ journey, is often glossed over. Granted, it is not nearly as exciting as the episodes with Odysseus—what could compete with the blinding of the Cyclops?—but Homer thought it important enough to include it in his poem, so it must serve a purpose. Some experts have suggested that the Telemachiad is one of Homer’s great displays of genius: When we begin the Odyssey, we have the same questions as Telemachus: Exactly who is this Odysseus? Why is he so important? And where the heck is he? These are the questions that Telemachus’ journey answers, and as we ride alongside him, we learn alongside him as well. By the time that Telemachus returns to Ithaca after visiting Nestor and Agamemnon, we have learned what we need to know and our appetites are whetted—we want to begin Odysseus’ part of the story, and that is what we get. The scene shifts to Odysseus and gives him a chance to tell his story thus far.

During his journey, Telemachus matures as he discovers what his father means to other people and realizes the hardships that he must have suffered. Before Telemachus sets out, he even questions whether or not Odysseus is really his father. By the time Telemachus returns, he is willing and ready to accept his father and also to forgive him for his 20 years of absence. It is not until the end of the poem that Telemachus and Odysseus are reunited, and it is a moment worth waiting for. In the squalid hut of Eumaeus the swine-herder, father finds son and son finds father. And it is exactly what both have been searching for.

DISCUSS

WRITE

Write a short piece about your father or a father figure in your life. How important is this person to you?

ANALYZE

Athena’s quote, “Few sons are the equals of their fathers,” shows a society where the older generation is superior to the younger. For example, Telemachus does not have the power to rid Ithaca of the suitors, but his father does. In Greek mythology, each generation of gods and men is less powerful than the one that came before. The heroes who lived before the Trojan War were mightier than the warriors who fought at Troy. Likewise, the gods were born less powerful than the Titans. Has this philosophy flip-flopped today? Does society believe that younger generations will always surpass the older? Explain. Why has this changed?

Homer Is a Her?

There is a great deal of mystery surrounding Homer, the poet who probably lived around 800 B.C. and has his name attached to two epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey. So much, in fact, that the mystery even has its own name: the Homeric Question. The question turns out to be many questions rolled into one. Here are just a few: Was Homer a real person? Was Homer just one person? Was Homer male or female? Did Homer write both the Iliad and the Odyssey? When were the poems written and for what purpose?

These epics originated from an oral tradition where poets chanted thousands of lines of poetry from memory before a live audience. (Whether Homer was actually literate and able to write the Iliad and the Odyssey down, or if he dictated it to someone else is another debate.) These bards, who must have had enormous memories, and an uncanny knack for ad-libbing when the need arose, traveled from one royal court to another performing their songs. In Book 8 of the Odyssey, Odysseus listens as one of these bards, a blind poet named Demodocus, sings about the destruction of Troy. The poet’s talent is so great that it moves Odysseus to tears. For centuries, readers assumed that this episode was Homer inserting himself into his story, and this assumption led to the tradition that Homer was a blind poet.

Another debate concerning the two poems is whether or not they are composed by the same author. The name Homer is connected with both, but in ancient times authorship was sketchy at best, with artists frequently attaching a more famous artist’s name to their work to boost its popularity. It has even been suggested that Homer was another way of saying John Doe.

If the two poems are written by the same author, it would make the Odyssey one of the most successful sequels of all time. But many have their doubts. In terms of tone, the Iliad is much different than the Odyssey. The Iliad is a war poem full of warriors, grit, glory, and death. Men and gods furiously duke it out against one another as they bring the 10-year-long Trojan War to a close. Contrast this with the Odyssey, where home and family—not glory and victory—are the ultimate goals. Some explain this discrepancy between the two poems’ themes with the theory that Homer wrote the Iliad as a young man and the Odyssey in his later years. After all, Achilles, the hero of the Iliad, is a young man, while Odysseus is middle-aged.

The Victorian author Samuel Butler wrote The Authoress of the Odyssey (1897) to make the argument that Homer was a young woman living on the island of Sicily. To back up this very specific theory, he argued that the author of the poem showed very little knowledge of sailing, knew more about domestic life (e.g., weaving, household chores) than a Greek man would have, and filled the poem with an overabundance of “female interest.” It is true that the Odyssey has much more “female interest” than the Iliad does. The war poem has only a handful of female characters, and for the most part, they stay on the sidelines. Contrast this with the Odyssey, which is filled with strong, crafty female characters—Penelope, Circe, Calypso, Athena—and has themes of faithfulness, love, and perseverance. Butler argued that another female character, the young princess Nausicaa, who discovers Odysseus when he washes up on the beaches of her kingdom, is actually the true author of the Odyssey, inserting herself into the poem.

These theories make for lively discussion, but there will never be any way to definitively prove that Homer was literate or illiterate, male or female, one author or two authors, blind or sighted. All credible details of his life are lost in antiquity. What we can hear is his voice—the way he masterfully tells a story—and while we may not know much about the man (or woman) behind these great works, the art will remain.

DISCUSS

Penelope, the Virtuous Wife

For centuries Penelope has been praised as the ultimate example of a virtuous wife. In the Odyssey she remains faithful to a husband, whom most consider dead, for 20 long years. A woman under extreme pressure—from a father who begs her to be remarried and a group of strong-armed suitors—Penelope rises to the challenge of faithfulness and keeps her cool. She also shows herself to be her husband’s match in intelligence and cunning. A trick nearly as famous as Odysseus’ Trojan horse is Penelope’s tapestry, which she weaves during the day and unravels at night.

Could a woman this crafty really be fooled by Odysseus’ disguises? Some believe that Penelope actually sees through Odysseus’ disguise when he appears in court dressed as a beggar. Why else would she immediately propose an archery contest that she knows only her husband can win? Maybe she is playing along with her wily husband. Even after Odysseus has revealed his identity, Penelope refuses to believe him until she puts him to another test. The marriage bed that Odysseus crafted 20 years before used a live tree—still rooted to the ground—as one of its legs. Penelope casually mentions that the bed has been moved to another room, and Odysseus cries out in shock: Did she saw the bed loose from the tree? His shock at her statement proves that he is really Odysseus, and she welcomes him home.

Penelope is not given a voice in Homer’s poem, and we are left to imagine her inner thoughts for ourselves. Modern writers have often tried to reinterpret the story from Penelope’s point of view. What was going through her mind during these many years of separation? Did she ever doubt Odysseus’ loyalty to her? If not, should she have?

FUN FACT

DISCUSS

WRITE

Write a letter from Penelope to Odysseus.

Journey's End

The return is an important part of every hero’s journey. As heroes reach their destinations, they think back on the journey, the many perils escaped, the many wonders seen, and the lesson learned along the way. In this light, “getting there is half the fun” takes on a whole new meaning. These heroes realize that it is not the destination that makes a journey, but the stops along the way.

For Odysseus, the return is the ultimate goal of his journey. With wife and son back in his arms, his kingdom safe and secure after many years of insecurity, Odysseus reaches his journey’s end.

Many people compare life to a journey—an odyssey—and like Odysseus’ journey, life is filled with many twists and turns and changes of fortune. When we reach the end of our life, we want to look back and appreciate the trip. We will remember the stops we made along the way, the occasions that we took time to have fun amid a hectic schedule. We will remember past friends and loved ones whose voyages diverged from our own. We will remember the many obstacles that we overcame along the way—that, in the end, made us a better person. If we can look back on our journey fondly, then the next journey will not be so frightening, the one that leads into uncharted waters.

Excerpt From “Ithaka” by Constantine Cavafy

As you set out for Ithaka

hope the voyage is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery . . .

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you are destined for.

But do not hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you are old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you have gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you would not have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you will have understood by then what these Ithakas mean. (Savidis, 1992, p. 36)

DISCUSS

Odyssey II: The Sequel

It is not only Hollywood that is sequel-crazy. The ancient Greeks were not satisfied with Odysseus simply reaching his home and settling down for old age. They thought there should be more to the story. After all, Odysseus has an adventurous heart, so ordinary life would not be for him. The Telegony, a lost poem that exists only through summary, tells the events that occur after the Odyssey. Rather than settling down like everyone expects him to, Odysseus goes back to sea, leaving Telemachus in charge of Ithaca, and sails around on another series of adventures. Meanwhile, Odysseus’ long-lost son, Telegonus, whose mother is Circe the witch, arrives in Ithaca searching for his father. Odysseus returns to Ithaca but, through a misunderstanding, is killed by Telegonus. Once true identities are revealed, Telegonus laments the fact that he has killed his own father. He takes Telemachus and Penelope back to Circe’s island, where Telemachus is married to Circe and Telegonus himself marries Penelope. Circe makes all four of them immortal, and they live happily ever after. This goofy story should be enough to show you that sequels are rarely a good idea. Homer never mentions (nor apparently has any knowledge of) these events, and they only complicate the perfectly fine ending of the Odyssey.

One Journey’s End Is Another Journey’s Beginning

Many authors, and not just ancient ones, have wondered what exactly happened after the Odyssey comes to a close. Like the author of the Telegony, they find it hard to believe that Odysseus would settle down to live an ordinary life once he had a taste of high adventure. They picture him to be like J.R.R. Tolkien’s Bilbo Baggins from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, who refused to go back to a humdrum life after so many adventures. The Victorian poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, made Odysseus (Ulysses) the subject of one of his most famous poems, “Ulysses.” Odysseus has grown older and itches to return to the open sea. He compares himself to metal that is rusting over; he declares that he will drink “life to the lees” (the last drop); he will knock the rust off his body and shine again; he will follow “knowledge like a sinking star, beyond the utmost bound of human thought.”

It little profits that an idle king,

By this still hearth, among these barren crags,

Match’d with an aged wife, I mete and dole

Unequal laws unto a savage race,

That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me . . .

I cannot rest from travel: I will drink

Life to the lees . . .

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnished, not to shine in use!

As though to breathe were life . . .

Come, my friends,

'Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew

Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. (Tennyson, 1842/1961, p. 284-286)

DISCUSS