Ear Today . . .

‘Hey, Dumbo. Come here and get your boots on.’

John, my brother, was by the door, ready to go to football training. I refused to answer.

‘Hey, has someone ordered a taxi with the doors left open,’ John continued, ‘cause there’s one right here.’ And he pointed at me and laughed.

I was used to this kind of thing and would try not to respond.

‘Hey, Dumbo, flap over here quickly or I’ll give you a good slapping.’

On it went.

I had a lot of serious problems to deal with as I was growing up, so being teased about my rather prominent ears – it was true, they did stick out a lot – wasn’t that big a deal at first. But it did start to get to me as I got older.

When I was a kid it was mostly my big brother and sisters who teased me, but when I reached my teenage years others started picking on me too. Most girls thought I was cute, in a Disney sort of way, but boys laughed and made jokes at my expense. Of course, if anybody my own size had a dig, I would swing at them as quick as look at them, and my ears were the cause of numerous fights as I grew up in Adelaide – though I got good at fighting for many other reasons too.

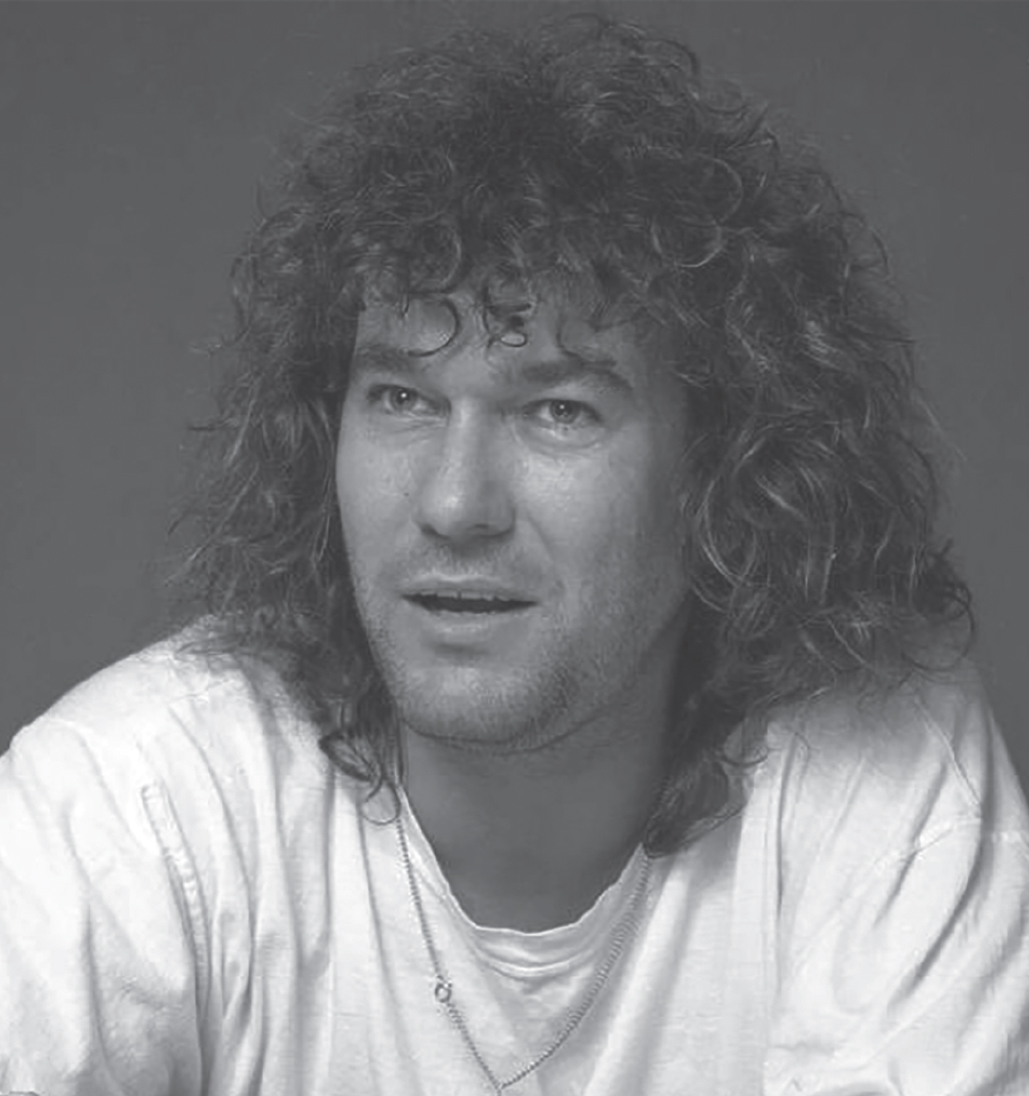

Then I left school and was able to grow my hair, and all that was left behind. My ears were forgotten about, hidden underneath waves of brushed fuzzy locks. Once I stopped combing my hair, they were constantly concealed by thick unkempt curls for about ten years. And I was happy.

There could be just about anything hiding in this hair.

But I didn’t want to keep my hair long all my life and in 1979 I decided to change things up a bit. In a moment of madness, I cut my hair short again. Suddenly, there I was, on the front pages of newspapers, ears sticking straight out like a wingnut. The headbands that I brought back from Japan to wear on stage, bearing slogans like ‘Death before dishonour’ and ‘Fight for freedom’, didn’t help me at all, as they just pressed what little hair I had left flat against my head, drawing even more attention to my ears.

All the embarrassment that I’d endured when I was little came rushing back at me. As a child I’d cringed when it was school photo time, but this was much worse. Now my head was on national television and on the covers of music magazines. A few times while making film clips, I was asked to put tape on the back of my ears to stop them glowing when the light shone through them. This was a whole new level of embarrassment.

I refused to let vanity get the better of me and just acted like my ears didn’t stick out at all. If anybody said anything, I punched them. At times I cut my hair even shorter so that people would say something – I wanted to fight.

This went on for a long time. I grew my hair long then had it shorn off at regular intervals. If my ears started to bother me, I grew it back. No problem.

My Jane loved my big ears and that was all that mattered. Our kids loved my big ears too. They would fold them and pull them and play with them.

‘Oh, I love your floppy, flappy ears, Dadda,’ Eliza-Jane would say, not knowing the damage these floppy, flappy ears had done to me. Still, I could put up with my ears as long as the people who loved me liked them.

In the mid-nineties, we moved to France to begin a new life. God knows I needed a fresh start at that point. I was going through a time of change that would carry on for years to come. As part of that change I decided it was time to fix my ears once and for all. For my fortieth birthday I would have my ears surgically pinned back. This was not like having my lips plumped or my cheekbones lifted to make me look younger; it was a procedure that was readily available and could in one fell swoop eliminate a source of a lot of grief for me.

Jane wasn’t convinced. ‘I love your ears, Jimmy,’ she kept saying. But I was adamant and made an appointment to see a doctor in the south of France.

I remember walking into the doctor’s office and suddenly feeling a sense of relief, especially when he told me it was a simple operation.

‘Oui, Monsieur Barnes. Thees, eh, ’ow you say, operation, can be done right ’ere. No need for going to l’hôpital.’

This was exciting; I couldn’t wait to be rid of those pesky ears. The doctor didn’t speak great English and my French was atrocious, but we seemed to be communicating quite well. I turned to Jane to see if I was understanding everything right. She looked concerned.

‘Would you like to have a general anesthésie or a local anesthésie?’ the doctor asked. At least I thought that’s what he’d asked.

‘Does it matter? I can have either anaesthetic – is that what you’re saying?’

The doctor just smiled reassuringly at me without responding. I looked at Jane again.

‘I think he’s saying it would be better if you had the general, Jimmy,’ she whispered.

But I’d already made my mind up. He’d said I could have either, so why would I want a general? The local would be quick and, hopefully, painless.

‘I’ll just have a local then, if that’s okay,’ I announced.

Jane shot me a disapproving glance. Now she was really worried. ‘Are you sure about this, baby?’

‘Yes. No problem. I’m doing it.’

As I always do when I decide to do something, I’d dived in the deep end. I knew this behaviour had got me into a lot of problems in the past, but I still couldn’t stop myself. I arranged to return the following day for the procedure.

Next morning I got up and took the two Valium tablets the doctor had given me and we headed for the surgery. Now I have never been very good with downers, and the Valium knocked me sideways. It didn’t calm me down as it should have done; in fact, it had the opposite effect. By the time we arrived at the doctor’s office, I was stumbling into walls and laughing about it while Jane tried to steer me in the right direction and stop me getting hurt before I’d even had the operation.

‘Hold on to my arm, darling, and I’ll get you across the road.’ Jane reached for me, but I was already moving. ‘No, Jimmy, the doctor’s is this way. Yes, that’s right, over here.’

Finally she got me into his rooms and sighed with relief. ‘Sit down and sit still and I’ll fill in the forms for you.’

But I kept jumping up and walking around. I was out of control.

Then the doctor took me into his office. Jane stayed in the waiting room – she couldn’t bear to see me cut up.

The doctor said, ‘If you sit here, I will give you the anesthésie locale.’ Then he tried to inject me with the anaesthetic. But I was still wagging my head from side to side like it was on a swivel.

Over the course of the next forty-five minutes, the doctor tried desperately to cut and stitch my ears between bouts of me leaping about.

‘What does that do?’ I’d say as I swung round to look at something on his desk.

‘Mon Dieu. S’il vous plaît, Monsieur Barnes! If you could just keep very, very still, I am trying to—’

Suddenly my head turned the other way.

‘Merde! I will have to start again. Er, ’ow you say: keep still, please!’

This went on for the whole operation. By the time he finished, I had a bandage wrapped tightly around my head, over my ears and under my chin. I looked like a rabbit or van Gogh in his famous self-portrait – quite appropriate for the south of France. The doctor was totally rattled and couldn’t wait to get rid of me. Happily, I’d felt no pain at all.

But not long after I got home, the local wore off and then I was in a world of pain. There must be a hell of a lot more nerves in my ears than I’d realised, I told myself. Of course, the fact that I hadn’t been able to keep still the whole time the surgeon was operating hadn’t helped either.

I was in pain for about two weeks and then, once the swelling went down, I was ready to look in the mirror.

I loved it. My ears swept back against my head just like those of a normal person. I had wanted this for as long as I could remember. Gone was the cause of so much torment in my life.

I’d decided early on that I wouldn’t make the procedure common knowledge, but nor would I keep it a secret. If anyone asked, I’d explain. But no one seemed to notice, which amazed me. Some people realised something was different, but they couldn’t put their finger on it.

‘You look younger,’ I remember one interviewer saying to me. ‘Have you had a face-lift or something?’

I looked him straight in the eye. ‘Don’t be fucking stupid. Do I look like I’ve had a face-lift?’ I wasn’t lying, but unless he could work out what I’d done, I wasn’t going to tell him.

In fact, no one has ever asked me outright about my ears. If they had, I would have happily spoken about it.

A few years after the operation, I was sure that my ears were changing shape. They started to stick out again. They were fighting back. But it turned out to be only just a little.

Many years on from my troubled and tormented childhood, I feel much better about myself. Am I at peace? The simple answer is yes. Does it have anything to do with my ears being pinned back? I’d have to say no. It’s more to do with the fact that after sixty years of pain and struggling, I have learned to live in my own skin. And if that skin still had ears that stuck out, I’m sure I would be happy living with them as they were.

Sometimes one of my family – usually Jane or Eliza-Jane – will try to turn my ears inside out, and fail.

‘I miss your old ears,’ they’ll say.

I haven’t told anyone this, but I miss them too.