There is no clear explanation of why a number of artists in and around New York City in the early 1960s, most of whom were known to one another distantly, if at all, should, each in his own way, begin to make art out of vernacular imagery—cartoon images from syndicated comic strips, or advertising logos from widely used consumer products, or publicity photographs of celebrities like movie stars, or pictures of things bound to be familiar to everyone in America, like hamburgers and Coca-Cola. In Spring 1960 Warhol bought a small drawing of a lightbulb by Jasper Johns at Leo Castelli’s gallery. When shown Lichtenstein’s large canvas that reproduced an advertisement for a Catskill resort, Warhol was mainly surprised that someone else was doing paintings of boilerplate advertisements, of the kind he was to display the following year in the Bonwit Teller window. As it happened, he was the fourth artist Karp had visited within a few months who worked with such imagery. A constellation of artists, all producing paintings of a kind as new as their content was familiar, was less a movement than the surface manifestation of a cultural convulsion that would sooner or later transform the whole of life. “This is a tremor of the twentieth century,” Karp thought to himself. “I felt it, and I knew it and I was awake to it.”

Once it emerges that several artists were engaged in similar projects, we explain it by saying that there was something in the air, and we no longer simply look for biographical explanations. Later in this chapter I shall write about Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, which have seemed to many to refer to his biography—that he ate that soup on a daily basis, for example. But in fact it would have seemed to Warhol that painting that kind of subject was a step toward becoming one of Castelli’s artists, and showing in his gallery, which specialized in a certain kind of cutting edge art. Castelli had taken on Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns—the artists Warhol admired most. He had just taken on Lichtenstein, whose art was close to what Warhol himself was producing, though Warhol had evidently been unaware of him. As Castelli’s director, Karp was on the lookout for artists doing art of just this sort—he would have had no interest in Warhol if he were painting abstractions. And Karp knew ten or twelve collectors also interested in this type of art whom he could bring to Warhol’s studio. Warhol did not yet have a gallery, but he belonged to an art world—a complex of dealers, writers, collectors, and, of course, other artists, that was disposed to taking his work seriously. And that art world was poised to become the defining institution of the mid-1960s, built around the kind of art the media was bound to notice and write about. When that happened, Warhol was to become very famous indeed, even if much of the press was negative. He became, in brief, a sensation.

The term Pop art was first used in 1958 by Lawrence Alloway, a British critic, initially to designate American mass-media popular culture, Hollywood movies in particular. Alloway’s contention was that these, like science fiction novels, were serious and worth studying, as much so as art films, high literature, and the products of elite culture in general. But by some sort of slippage, the term came exclusively to designate paintings—and sculptures—of things and images from commercial culture, or objects that everyone in the culture would recognize, without having to have their use or meaning explained. Warhol’s first show in Bonwit’s window was part of what would become an art movement the following year. Comic strip personages—Nancy, Superman, Popeye, the Little King, Dick Tracy—entered American artistic consciousness in the early 1960s in somewhat the same way that the imagery of Japanese prints entered advanced French artistic consciousness in the 1880s, with the difference that, however popular the prints were in Japan, they were exotic in France, while the American comics, with few exceptions, were dismissed as trash everywhere except in the art world, where they were exciting images because they implied a revolution in taste. These images had ascended, through Warhol and Lichtenstein, into the space of high art. It was their popularity that recommended them to the Pop artists, which gave a kind of political edge to their promotion as art to be taken seriously.

How different this brash and irreverent art was from the culture of Abstract Expressionist painting, where meanings were personal and arcane, and expressed through pigment so energetically brushed, dripped, or splashed across large expanses of canvas that viewers were left with little to say in response except, “Wow!” Not that there was much to say in front of Pop art, since everyone knew what it was about. The question was what made the elements of everyday life all at once so compelling—what could the interest be in comic strip figures, or soup labels or icecream cones? Why would anyone want to paint, or make effigies, of them? Everyone in the culture was already so entirely literate in their meaning and rhetoric that the only question they seemed to raise was in what respect they could be considered art. From the perspective of the Abstract Expressionists, they could be so considered only by the “gum-chewing pinheaded” delinquents who, a noted critic declared, were beginning to populate the galleries, saying, presumably, “Wow,” when they were not merely whistling through their teeth.

So it is not uncommon for commentators to explain this art simply as a predictable reaction against Abstract Expressionism. But there were many forms a reaction could take. Abstractionists could go back to nongestural abstract painting, as the so-called Hard-Edged Abstractionists did. Or painters could go back to landscapes and still lifes. But there was something in-your-face about Pop art. Yes—everyone knew who Superman and Mickey Mouse were. But it took some special courage to accept a painting of either of them as high art. In my preface, I describe the shock with which I first saw, in 1962, a black-and-white reproduction of Roy Lichtenstein’s painting The Kiss in ARTnews, the leading and most authoritative art publication of the time. It looked like a panel from Terry and the Pirates or Steve Canyon, but it was instead used to illustrate a review of Lichtenstein’s first one-person show at Castelli’s. I found it deeply disturbing, though I ultimately came to feel that, if that was art, anything could be art—anything! Years later, I heard Lichtenstein say that his aim was to overcome the distinction between high and low art by getting a painting of a comic strip panel into an art gallery. There was something revolutionary, something of what Nietzsche called the “transvaluation of values,” in Lichtenstein’s attitude. It condemned to irrelevance everything that belonged to art appreciation. Artists who made this turn were not simply reacting to Abstract Expressionism, they were revolutionizing the concept of art. They were pressing against a boundary. Imagine someone hanging a painting of a tin of shoeshine polish in his or her home, rendered literally, so one could not admire the brio of the brushwork—a painting that could have appeared in a magazine as an advertisement for shoe polish. What could that mean? It would mean at least that the owner of the painting had himself crossed a boundary, and was making a statement about art, and about himself.

Revolutionary periods begin with testing artistic boundaries, and this testing then gets extended to social boundaries more central to life, until, by the end of that period, the whole of society has been transformed: think of Romanticism and the French Revolution, or of the Russian avant-garde in the years 1905 to 1915 and of Aleksandr Rodchenko’s slogan “Art into life!” Strictly speaking, I think that the era of Modernism began to break up with the advent of Dada in 1915 as a revulsive reaction to World War I. It took place initially in Switzerland, which had remained neutral. The reigning idea was that artists were no longer prepared to make art for the pleasure of the ruling classes in Europe, whom they held responsible for the deaths, in the name of patriotism, of millions of young men and the devastation of civilian populations. The Dada artists felt powerless to do anything other than begin to make art that was disrespectful of the classes that had patronized the arts, and to mock the very idea of the Great Artist, whose work brought glory and edification to those in power. The emblematic Dada work was Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q.—a mild French obscenity when the letters are pronounced—printed across the bottom of a postcard of the Mona Lisa, on which the artist drew a moustache. Duchamp was the central figure of provocative disrespect that bridged the Dada revolt and detonated the attack against boundaries that defined Modernism. The culminating Modernist aesthetic was political. It consisted of the great monolithic states, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in particular, the regimentation of life, and the glorification of war. Abstract Expressionist paintings were very far from the political vision of these states and their concept of power. They are, indeed, celebratory of personal privacy. But in their scale and power they are also celebratory of the spirit of heroism, which Dada began its adventure by mocking. Abstract Expressionism was the last great artistic expression of the Modernist spirit.

There were certain centers in America in which artistic innovation of a certain kind was encouraged in the 1950s: Black Mountain College, where Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly were students and John Cage was a teacher; the seminar in Zen Buddhism taught by D. T. Suzuki at Columbia University, attended especially by avant-garde composers like John Cage and Morton Feldman, and by artists like Philip Guston and Agnes Martin; and then Cage’s own course in experimental composition at the New School for Social Research, out of which Fluxus, a radical art and music movement, was formed, committing itself to “overcoming the gap between art and life.” The Fluxus slogan echoed Rodchenko’s “Art into life” agenda, and found expression in Robert Rauschenberg’s statement in the catalog for the 1959 Museum of Modern Art exhibition Sixteen Americans, in which he wrote: “Painting relates both to art and life. I try to act in the gap between the two. There is no poor subject. A pair of socks is no less suitable to make a painting than wood, nails, turpentine, oil, and fabric.” Rauschenberg should have used the word “art” rather than “painting.” He was giving himself license to use anything he wanted to use for making a work of art. By the early 1960s this inclusionary impulse extended itself to dance. A dance movement could consist of sitting in a chair, eating a sandwich, or ironing a skirt. The question “What is dance?” joined the questions “What is music?” and “What is painting?” Where and how was the line between art and life to be drawn? As the 1960s progressed, the testing of cultural boundaries became the defining project of the decade.

Pop art was part of the cracking of the spirit of Modernism, and the beginning of the Postmodern era in which we live. In December of 1961, Claes Oldenburg turned a downtown store on the East Side of Manhattan into a place in which he would sell his sculptures, which were made of plaster, chicken wire, and cloth, painted over with household enamel to form crude representations of everyday things—dresses, tights, panties, cake, soda cans, pie, hamburgers, automobile tires. It was more like a general store than an art gallery, and Oldenburg indeed called it “The Store,” as if the sales place and the items for sale constituted an artwork. Oldenburg was the storekeeper who wrote out sales slips. The merchandise was displayed in the store window. People bought art from it the way they bought groceries from grocery stores, or dry goods from dry goods stores. It was obviously very different from the smart display windows of Bonwit Teller, in which Warhol had displayed his art in April. In a sense, Oldenburg’s was an act of institutional critique. It was a critique of the air of preciosity art galleries and museums created to reflect on the preciousness of the art they showed. It too was a way of overcoming the gap between art and life. But it was also a way of becoming known very quickly, if your work attracted media attention.

Since at least the Armory show of 1913 (in which Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase was the paradigm of avant-garde art) the doings of avant-garde artists made good copy. What caused Warhol to begin to paint the advertisements and cartoons he installed for a brief time in the Bonwit Teller window is one of the deep mysteries of his biography. But there is no such mystery regarding his decision to paint cans of Campbell’s soup. He wanted to become very famous very quickly, and nothing could achieve that for him that did not attract media attention. He was a Pop artist before the meaning of the term was stabilized, but Pop in 1962 was what caused people to talk.

There are various stories about where Warhol got the idea for the Campbell’s Soup Cans, but it is worth examining at least one of them—an encounter with an interior designer, Muriel Latow, whom he begged for an idea. There are enough such stories to suggest that this was a regular pattern with Warhol. He got his ideas from others much of the time. In a 1970 conversation with Gerard Malanga, his assistant and sidekick, Warhol said, “I always get my ideas from people. Sometimes I don’t change the idea. Or sometimes I don’t use an idea right away, but may remember it and use for something later on. I love ideas.” Warhol told Latow he needed something “that would have a lot of impact, that would be different from Lichtenstein and Rosenquist, that will be very personal, that won’t look like I’m doing exactly what they’re doing.” Latow told him that he should paint something that “everybody sees every day, that everybody recognizes . . . like a can of soup.” The form of Warhol’s question ruled out a lot of possibilities. He was not interested in being told to do a nice, cheery abstraction, or Manhattan by moonlight, or a pretty girl reading a letter by the window. It had to be something from the common culture that hadn’t already been done by someone else. It had to be something people would talk about without having seen it. How many people have actually seen the diamond encrusted skull that Damien Hirst is alleged to have sold for a hundred million dollars? But that doesn’t keep them from wondering how much it is really worth, who would buy it, what it meant, why anyone would do it.

It is one thing to be told to paint soup cans, another to determine how the painting or paintings should look. Warhol’s response was far more than simply a painting of a soup can. It was an eight-by-four grid, consisting of each of the thirty-two varieties of Campbell’s soups produced at the time—like an installation of portraits of notable personages. Warhol put into effect what he had learned from Emile de Antonio: the paintings had nothing painterly about them, but looked as if they were mechanically reproduced, as indeed they were, since Warhol used a silk-screen process to achieve a look of perfect uniformity. In any case, the array is severely frontal, like Byzantine portraits, and the four rows of eight paintings each were like an up-to-date iconostasis—a wall of icons such as the one in the Orthodox church in which Andy’s mother, Julia Warhola, worshipped in Pittsburgh when he was growing up. Or a regularly stacked set of supermarket shelves, which embodied an aesthetic that greatly engaged Warhol. None of the other Pop artists used this sort of format, in which essentially the same image was repeated and repeated. Even when he came to do portraits, later in his career, Warhol favored using a block of the same picture of the same person in different colors. The Campbell’s Soup Cans were portraits, in that each contained a different variety of soup, the name of which was printed on its label. Repetition came to be one of the master elements in what could be called the Warhol Aesthetic.

There is a question of genre that applies to almost everything Warhol did at the time—whether there were thirty-two paintings, or one installation consisting of thirty-two parts. My sense is that he had in mind the entire array as a single work. They were projected and then touched in by hand. He could have turned out as many of each variety as he wished. But he did only one of each, suggesting that he was bent on making a wall of soup cans, consisting of thirty-two unique units. When the work was exhibited at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in July 1962, however, they were displayed in a single line, placed on a narrow shelf around the gallery. And they were evidently sold one at a time, for $100 each. But the dealer, Irving Blum, increasingly felt that the paintings belonged together, “as a set,” as he put it. Warhol was pleased by Blum’s decision, since they were “conceived as a series.” Blum was able to buy back the ones he had sold, and Warhol set a price of $1,000 for what was now recognized as a single work. Blum sent him $100 a month until it was paid up. And they began to be exhibited as a single unit, a matrix.

The Campbell’s Soup Cans were already famous before anyone other than those who dropped by Warhol’s studio had really seen them. They were described in Time magazine in May 1962. This was publicity of a kind that registered these works as a cultural rather than merely an art world event—that whatever the art world might have thought, Warhol was on his way to being an American icon. It hardly mattered whether the publicity was good or bad: the art world thrived on controversy. Warhol came to the attention of Eleanor Ward, who owned the stable Gallery, which in fact was originally housed in a former stable on West Fifty-eighth Street near Seventh Avenue. She asked Warhol’s mentor, Emile de Antonio, to take her to Warhol’s studio. She made him a deal; if Andy would paint a portrait of her lucky two-dollar bill, she would give him a show in November of that year. (In addition to soup cans, Muriel Latow had suggested that Warhol paint pictures of money.) Ward had an eye for serious art. Rauschenberg and Twombly were two of her artists. She had shown Robert Motherwell, and had just taken on Marisol and Robert Indiana. But more than any of them, Warhol’s Soup Cans raised the question of what was art in a way that could not be resisted.

Everyone’s conception of art was of something spiritually rich that belonged in gold frames and that hung on museum walls, or in the mansions of the wealthy. In his biography of Warhol, Victor Bockris interviewed one of Warhol’s earlier friends, Charles Lisanby, who flatly turned down the offer of one of his portraits of Marilyn Monroe. “Just tell me in your heart of hearts you know it isn’t art,” he said to Warhol. “He would never have admitted it, but I knew he knew that it wasn’t” (p. 157). It is hard to know what Warhol thought of such questions, but I feel that he knew that he had taken art to a new place. As a teenager, I haunted the galleries of the Detroit Institute of Art, in which there were shiny oil paintings of saints, of princes on horseback, of ladies in long satin skirts reading love letters. To imagine that a flat and faithful image of a can of Campbell’s soup would have been a work of art, fit to hang in their company, would have been unthinkable. Other than the fact that it was a painted picture, it would seem to have nothing in common with what anyone thought art was. It was part of life, but hardly a piece of what anyone would have recognized as art. At the very least a philosophical definition of art would have to apply to it as well as to El Greco’s saints, or Terborch’s Dutch beauties, or Velázquez’s royal personages. If a definition was to do that, it would have to be emptied of everything that applied to these masterpieces but did not apply to the painting of the soup can. All at once, the Campbell’s soup can invalidated as insufficiently general the entire canon of philosophical aesthetics, and at the same moment defined its time. It was, as de Antonio said, who we are.

Warhol painted Campbell’s soup cans throughout his life. After the Ferus Gallery soup cans, there were paintings of a hundred, and even two hundred, Campbell’s Soup Cans. Then there were paintings of Campbell’s soup cans in which the cans were undergoing some kind of martyrdom—being pierced with a can opener, or crushed, or flayed by having the label torn off. These belong in spirit with the various paintings of human disasters that he was shortly to turn to—car crashes, airplane crashes, and the like. The formats he discovered for showing the cans feel almost like formats for religious painting—choruses, assemblies, iconostases, where the cans were understood as vessels for our daily soup. There was a steaming bowl of Campbell’s soup leaning against the far wall of his studio when he left it for the last time, when he went to the hospital for the operation that was to kill him in 1987. It is next to a double Jesus, from the Last Supper variations he did in his last years. It really did meet his demand that, whatever “idea” Latow was to give him, it had to be personal. What he admired about commercial culture was the uniformity and predictability of everyday manufactured food. One can of Campbell’s tomato soup is like every other can. No matter who you are, you cannot get a better can of soup than the next person. Wittgenstein said that he did not care what he ate as along as it was always the same. The repetition of instantly recognized food containers—Campbell’s cans, Coca-Cola bottles—was an emblem of political equality. It was not simply a formal device of advanced painting.

In November 1962 Warhol’s show opened at the Stable Gallery, which had since relocated to an elegant town house on East Seventy-fourth Street. A week earlier, three of his works appeared in a show called “The New Realists” at the Sidney Janis Gallery on Fifty-seventh Street, curated by the French critic Pierre Restany, who was associated with the Nouveau Realiste movement in France. The Janis show may have appeared to be an effort to absorb Pop into the European movement, and at the same time declare that the Abstract Expressionist movement had come to an end, since Janis’s gallery had represented several of its leading figures. To turn its space over to the Pop and the New Realists seemed a betrayal of the values of the New York School in favor of the values of the “gum-chewing, pinheaded delinquents.” Several of the older artists resigned in protest.

Certainly a line was being drawn between two periods of artistic production in New York, but even more, though this was less evident at the time, between two periods of art history. The 1960s effectively saw the end of Modernism and the beginning of an entirely new era, which Pop exemplified. But Pop was also too American in spirit to be easily absorbed into a single movement with the Nouveaux Realistes, which was essentially an expression of European values. The robust Americanism of Pop was perhaps accentuated by the end of the Cuban missile crisis on October 26 of that year. The sudden lifting of the threat to the entire form of life the Pop artists celebrated must have added a certain luminosity to such innocent artifacts of the American soul as Campbell’s soup and Coca-Cola. I remember, as a Fulbright student, sitting in an audience addressed by Janet Flanner, the expatriate New Yorker writer, who told us that the stomach is the most patriotic of organs, that there were times when the craving for certain foods that could not be satisfied in Paris was overwhelming.

There were eighteen rather heterogeneous works in Warhol’s first Stable show: three so-called serial works of one hundred soup cans, one hundred Coca-Cola bottles, and one hundred dollar bills, as well as Red Elvis—a serial array of thirty-six Elvis heads. There were two paintings with Marilyn Monroe as subject, one of which, consisting as it did of fifty Marilyn heads, could have been counted as a serial painting, as could a silk-screen painting of the baseball player Roger Maris swinging a bat, over and over and over, in front of a catcher, like a recurrent memory. Then there was Dance Diagram, a large black-and-white painting of where to put one’s left and right foot, together with the connecting lines to be following in executing a step; and Do It Yourself (Flowers), a brilliant “painting by the numbers” painting. There were no comic images of the sort included in the Bonwit Teller show, Warhol having left that genre of Pop to Roy Lichtenstein. Finally, there was the first of Warhol’s Death and Disaster paintings, 127 Die. A reviewer would have had a hard time putting this all together as a consistent oeuvre. But it made clear that Warhol was more than the painter of soup cans.

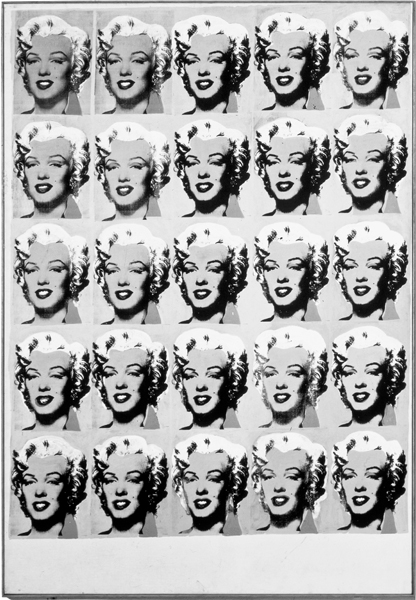

Dance Diagram and Do It Yourself (Flowers) belong with the grainy advertisements of the Bonwit Teller window display, if we think of the latter as a kind of portrait of everyman and everywoman, with their inventories of minor aches and pains, and the cosmetic blemishes that make them, in at least their own minds, unattractive, and hence unlovable and lonely. Learning to dance presents itself as a way of overcoming the loneliness: one can hold a partner while the music plays, and feel the other’s warmth. Learning to paint by buying a kit and filling in the numbered areas on a canvas board with pigment is a pathetic effort at selfimprovement by acquiring an “accomplishment” that involves no talent whatsoever. It only underscores the distance between one’s life and that of the celebrities that makes one feel inferior. But even the celebrities are not that happy. Marilyn Monroe committed suicide the day that Warhol’s show at the Ferus Gallery closed. Warhol painted her beautiful head as if it were the head of a saint on a field of gold leaf in a religious icon. She was Saint Marilyn of the Sorrows. Her beauty was a mask. Warhol’s skills as a commercial artist stood him in good stead when he began to execute Marilyn Monroe paintings. He drew a frame around her head in a publicity photograph for the film Niagara and had it made into a silk screen. This, in effect, made her face into a mask, which he could reproduce over and over again. In fact, Warhol did twenty-four Marilyn paintings, the most spectacular of which was Marilyn Diptych, which was included in his first Stable Gallery show.

The colors in Marilyn Diptych were garish—chrome yellow hair, chartreuse eye shadow, smeary red lipstick. There were two sets of twenty-five Marilyns, colored on the left, black and white on the right. The colored ones are fairly uniform, even if off register. The black-and-white ones show a certain variation. In the second row from the left, for example, the screen gets clogged with the black ink, as if a shadow had fallen over the star’s face. Then the features get paler and paler until, in the upper right corner, the face feels as if it is fading away from the world as we read across the diptych. It is like a graphic representation of Marilyn dying, without the smile leaving her face. In this respect the fifty faces of Marilyn Monroe is very different from the array of thirty-two Campbell’s Soup Cans, which are uniformly bright. There is no internal transformation. In Marilyn Diptych there is repetition, but it is a transformative repetition, in which the accidentalities of the silk-screen medium are allowed to remain, like the honks and squawks of a saxophone solo, in performances by John Coltrane.

The one anomalous work was 129 Die. It was the front-page photograph of a jet crash in the New York Mirror for June 4, 1962. Henry Geldzahler, the curator of contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum, brought it to Warhol, saying, “It’s enough life. It’s time for a little death.” He wanted Warhol to change from the celebrator of consumption to something deeper and more serious. Warhol was to spend much of the following year making Death and Disaster silk-screen paintings: car crashes, plane crashes, race riots, suicides, poisonings—the disasters we see on the evening news, or that get written about in the tabloids and then forgotten, as if violent deaths happened to others, to people we know nothing about. They are like illustrations to Marcel Duchamp’s mock epitaph—D’ailleurs, c’est toujours les autres qui meurent—“Anyway, it’s always the others who die.” Like the batter who dreams, over and over again, of a base hit or a strikeout, the disasters are repeated and repeated in a single frame, as if to dull the horror. You cannot die more than once—“After the first death there is no other,” as the poet Dylan Thomas wrote—though Warhol did in fact die twice. But what does it mean, showing people dying the same death over and over? Warhol used decorator colors for these paintings, lavender and rose and orange and mint-green—as if he were producing wallpaper. Sometimes he would pair a disaster painting with a blank monochrome canvas in the same color. It made for a more impressive work than the disaster taken alone. But it points to a contrast as well, between the world of disaster and devastation and the void—the world emptied of incident, lavender emptiness.

Dying in America. Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962. Synthetic polymer paint and silk-screen ink on canvas, 82 × 57 in. (205.4 × 144.8 cm). Tate, London/Art Resource, NY

The 1962 Stable show was a huge success, critically and financially, though Warhol’s prices were unusually modest. But in a way Warhol himself was carried along with his work, as if he were inseparable from it, with his wig, his weak eyesight, his bad complexion, his loopy, ill-defined musculature. Who, unless they knew Lichtenstein or Oldenburg or Wesselman or Rosenquist personally, had any idea of what they actually looked like as men? But Andy became as recognizable as Charlie Chaplin or Mickey Mouse. He became a public personality. With the first Stable show Warhol became Andy, the Pop artist—an icon, identified with his bafflingly obvious work, and with the world in which Americans lived. He was the one that took that world and turned it into art that everyone felt they understood. Much of the publicity was negative, but there was a lot of it, and it didn’t matter what it said.

One the best critics of the time responded to what the negativity left untouched. Michael Fried, cultivated and sophisticated as few journalistic critics, captured the great truths of the Stable shows: “Of all the painters working today in the service—or thrall—of a popular iconograph, Andy Warhol is probably the most single-minded and the most spectacular. At his strongest—and I take this to be the Marilyn Monroe paintings—Warhol has a painterly competence, a sure instinct for vulgarity (as in his choice of colors) and a feeling for what is truly human and pathetic in one of the exemplary myths of our time. That I for one find moving.”

The tragedy of the commonplace—“beauty falls from air, queens have died young and fair”—is as true of New York and Los Angeles in the 1960s as it was of Paris and Lombardy at the time of the Renaissance. No one standing in front of Marilyn could say—how cheap, how empty. Warhol, in giving us our world transfigured into art, transfigured us and himself in the process. Even if the Death and Disaster paintings did not sell, even if Pop’s days were numbered, ours was becoming the Age of Warhol. An Age is defined in terms of its art. Art before Andy was radically different from the art that came after him, and through him.