In 1774, the people in 13 of Britain’s North American colonies were on the brink of rebellion. War then erupted west of the Appalachians between Britain’s greatest colony, Virginia, and the Mingo and Shawnee Indians of what is now Ohio. As George Washington and other Virginia delegates traveled to Philadelphia to attend the first Continental Congress, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, the last royal governor of the colony, led more than 2,400 other Virginians against the Indians.

In what would be remembered as Lord Dunmore’s War, two Virginia militia armies invaded Ohio. Dunmore led one and his American subordinate, Col. Andrew Lewis, the other. Many of the officers and men in the armies would become famous figures of the Revolutionary War and frontier history.

On October 10, 1774, about 700 Indians attacked Lewis’s 1,100-man army. The victory of the Virginians at the battle of Point Pleasant, which opened Kentucky to American settlement, allowed the independent United States to include what are now the states of West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin within its boundaries after the Revolutionary War.

In 1774, Britain was the world’s pre-eminent power. The population of Britain, about 10 million, included a million Scots, one-third of a million Welsh, and 7 million English, whose numerical and cultural predominance was so great that Britain was often known as England. In British Ireland, there were about 1.5 million native, Catholic Irish and a half-million Protestant immigrants. Across the Atlantic, Britain had 19 North American colonies. Although six had few inhabitants, the 13 that stretched down the Atlantic coast from Massachusetts to Georgia had a population of about 2.6 million.

In 1749, a French expedition left lead plates at six points along the Allegheny and Ohio rivers to claim the land drained by the rivers and their tributaries for France. This plate was left on August 20, 1749, at the mouth of the Kanawha River. (Virginia Historical Society)

Britain’s supremacy followed its victory over France in the French and Indian War. That conflict, known in Europe as the Seven Years War, arose from rival French and British attempts to control the Ohio Country, the area that is now western Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky. The French first tried to stop the activities of men like the British trader George Croghan. On June 1, 1752, Ojibwe and Ottawa Indians, allied with the French, destroyed the most important center of British trade in the Ohio Country, Pickawillany, a Miami Indian village on the Miami River.

From 1745 to 1752, George Croghan was the leading British trader in the Ohio Country. In 1749, he probably built this stone structure as part of a trading post near present Isleta, Ohio. (Author’s photograph)

The French then began building forts to guard the area, including Fort Duquesne at present-day Pittsburgh. In 1754, George Washington led a colonial militia force to stop the construction. Attacked on July 3, 1754 by a larger French and Indian army, Washington’s 400 militiamen were forced to surrender to the French at a small British fortress, Fort Necessity.

Washington’s army at Fort Necessity included militia companies led by Andrew Lewis and Adam Stephen. This reproduction of the crude fort is at Fort Necessity National Battlefield, near Farmington, Pa. (Author’s collection)

In the war that followed, the Indians of the Ohio Country fought as French allies. Their prowess in combat in the western woods then defied British efforts to defeat them. They destroyed British armies at Monongahela on July 9, 1755 and Grant’s Defeat on September 14, 1758. An advance by Gen. John Forbes in 1758 forced the French to evacuate Fort Duquesne. The British were otherwise unable to invade the area.

British victory at the battle of the Plains of Abraham on September 13, 1759, however, denied use of the St Lawrence River to the French. Unable to supply their western outposts, they surrendered their Ohio Country forts to Britain in 1760. In 1763, they acknowledged loss of all of France’s North American territory.

In the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the British government announced that, until further notice, the Ohio Country would be left to the Indians, traders, and the garrisons of the British forts. Any further colonial settlement there was banned. But the Ohio Indians, led by the Ottawa chief Pontiac, nonetheless decided to renew the war that France had lost. On May 16, 1763, they captured by deceit British Fort Sandusky in northern Ohio, and on July 31 defeated a British force at Bloody Run. They were unable, however, to take the main British strongholds in the west, Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt, which the British had built at the site of Fort Duquesne. They also failed to destroy a force sent to relieve Fort Pitt. On August 5–6, 1763, about 200 Indians attacked 500 men led by Col. Henry Bouquet at Bushy Run. There the brilliant Bouquet saved his army from annihilation by devising a feigned retreat and bayonet charge by concealed soldiers.

These re-enactors are at the site of Bouquet’s victory, now Bushy Run Battlefield, near Harrison City, Pa. (Photography by Amanda Wilson)

In 1764, when Bouquet and Maj. Gen. John Bradstreet invaded Ohio with much larger armies, the Indians ended Pontiac’s War without further battle. The interest of the British government in the Ohio Country then waned. Except for Forts Michilimackinac, Detroit, and Niagara, the British began abandoning their strongholds west of the Appalachians.

Sir William Johnson, the adopted Mohawk who served as British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies, then labored to avoid any further Indian wars. In Pittsburgh, a village that had arisen at the site of Fort Pitt, Croghan served as Johnson’s deputy. There he oversaw relations with the Ohio Indians with his assistant, the Shawnee Alexander McKee.

Because of wars between the Indians, that part of the Ohio Country south of the Ohio River was uninhabited. There, in present-day West Virginia and Kentucky, only hunters and war parties roamed. The Iroquois of New York, a confederacy of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca tribes, claimed dominion over the area. So did their enemies the Cherokee of Tennessee and Georgia. In 1768, a British attempt to obtain the land for settlement succeeded. The Iroquois sold their claim in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, and the Cherokee in the Treaty of Lochaber.

Virginia claimed all, and Pennsylvania part, of the area as within their colonies’ borders. But in 1769, the British government approved a proposal to create a new North American colony in the area, Vandalia. From the new colony’s capital, at the mouth of the Kanawha River, its government would rule the area that is now southwestern Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and eastern Kentucky.

In 1770, Johnson was able to make the proposed colony safer for settlement by negotiating peace between the Iroquois and Cherokee. The prospects for attracting settlers to Vandalia then appeared bright. Since the outbreak of the French and Indian War, the population of the British colonies in North America had more than doubled. The largest American town, Philadelphia, had about 35,000 people. New York, Boston, and Charleston followed, with populations of about 25,000, 16,000, and 12,000.

To visitors from London, which in 1774 had nearly a million people, such places appeared prosperous but unimpressive. To them, the American colonies resembled very provincial areas of England. From Boston to Charleston, bewigged gentlemen and gowned ladies presided over political and social affairs of only local importance. Around them lived men and women of humbler status, who ranged in states of respectability from flourishing farmers and tradesmen to servants and black slaves.

To prevail in the French and Indian War, Britain had incurred a crippling debt. To the financially pressed British, it seemed fair that the American colonists should share the cost. The British government therefore had legislated that the Americans must buy imported goods only from Britain, and pay a variety of special taxes.

The colonists responded to the legislation with an outrage that bewildered the British. They had often quarreled with one another. Colonial border disagreements had sometimes even led to armed conflicts. From 1732 through 1736, Marylanders led by Thomas Cresap had battled Pennsylvanians in a dispute ultimately resolved by the Mason–Dixon Line. But now anger united the Americans. A government in London, elected by men who lived across the Atlantic, appeared to recognize no limit to its power over them. It had, moreover, stationed an army of more than 7,000 soldiers in the colonies. On December 16, 1773, men destroyed tea on ships in Boston harbor to protest against one of the new taxes. As 1774 began, the colonists nervously awaited news of what the British response to the Boston Tea Party would be.

Few visitors from London ever followed the rough roads and horse trails that led west toward the Appalachian Mountains. As late as 1720, the colonists had all lived within 100 miles of the Atlantic coast. Then British immigrants of a different kind had begun to arrive. Their medieval ancestors had lived on the border between Scotland and England, where the march lords had warred, and raiding had been a way of life. In the late 16th century, many had begun migrating to Ireland, where these Protestant newcomers had fought the native, Catholic Irish in the bitter wars of Elizabeth I, Cromwell, and William of Orange.

About 1720, some began arriving in America, where they would be known as the Scotch-Irish. In the main colonial towns, where their customs marked them as aliens, they found a frigid welcome. Most, moreover, like two-thirds of all immigrants to America, had paid for their passage by selling themselves to ships’ captains as indentured servants. Auctioned off in the Atlantic ports, they became, in effect, slaves with fixed dates of emancipation. During their servitude, which lasted as long as six years, their fates depended upon the benevolence of their purchasers. Some were well treated. Others were beaten or even kept in chains. When their terms of servitude ended, they wanted, above all, lives in which they and their children would not be the servants of others.

In 1763, 19-year-old Ann Bailey emigrated to Virginia as an indentured servant. When her husband fell at Point Pleasant, she became a famous scout and Indian fighter. This engraving from Henry Howe’s 1848 Historical Collections of Ohio preserves a sketch of her by an anonymous 18th-century artist. The celebrated frontierswoman is buried at Tu-Endie Wei/Point Pleasant Battlefield State Park. (Author’s Collection)

The Scotch-Irish, and other immigrants who joined them, left the existing colonial towns and farms with instruments of independence: axes to build homesteads and clear fields, and firearms to hunt and defend themselves. They followed first an Indian path, the Iroquois War Trail, which they widened into the Great Wagon Road. It led from Pennsylvania to the Shenandoah River Valley in Virginia, and on through the headwaters of the James and New rivers. The most venturesome followed Indian trails along the Holston River to what is now Tennessee, and through the western range of the Appalachians into what are now southwestern Pennsylvania, western Maryland, and West Virginia.

There these vigorous and self-reliant people settled, often tens of miles from their nearest neighbors. Those who complied with their colony’s land laws had their sites surveyed, and took the maps to the nearest towns for recording. If no rival claimants objected within six months, the land was theirs. Others just demonstrated their claims by blazing on tree trunks the outer limits of their domains.

They found danger on the frontier. In 1742, 28 Iroquois warriors, returning from an expedition against the Catawbas in South Carolina, killed the cattle of settlers living near the James River. When 35 settlers confronted them on December 19, 1742, the encounter ended in battle. Eleven settlers and eight Iroquois died at McDowell’s Fight. Payment of compensation to the Iroquois by Virginia then ended the threat of war. Then, in 1744, the Shawnee chief Peter Chartier led a small band of warriors in raids against the frontier settlers to aid the French during King George’s War. Such conflicts with Indians, however, were rare. The Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia colonists had not experienced war with the Indians since 1677.

The prisoners taken by Chartier’s warriors in 1744 included 12-year-old Catherine Cougar. After five years of slavery in a Shawnee village on the Pickaway Plains, she was sold to French traders and ultimately returned to Pennsylvania. When she emigrated with her son to Ohio in 1798, she discovered that the land he had purchased was the site of the village. This monument is at the site. (Photograph by Dale Benington)

But in 1755 the French persuaded the Ohio Indians to attack the western settlers in the French and Indian War. Neither British soldiers nor colonial militiamen could protect them from the onslaught. The terrorized settlers abandoned whole counties in their flight to refugee camps on the Atlantic coast.

But these descendants of many generations of warriors soon learned how to defend themselves. In 1756, they still sang in Scotland the ballad “Johnnie Armstrong,” the tale of a fierce border raider who had died in about 1530. In the only success of the British in battling the Ohio Indians during the French and Indian War, his descendant John Armstrong led 300 Pennsylvania frontiersmen against Kittanning, a large Delaware village on the Allegheny River. On September 8, 1756, they surprised its 50 defenders, killed 20, and freed 11 captives.

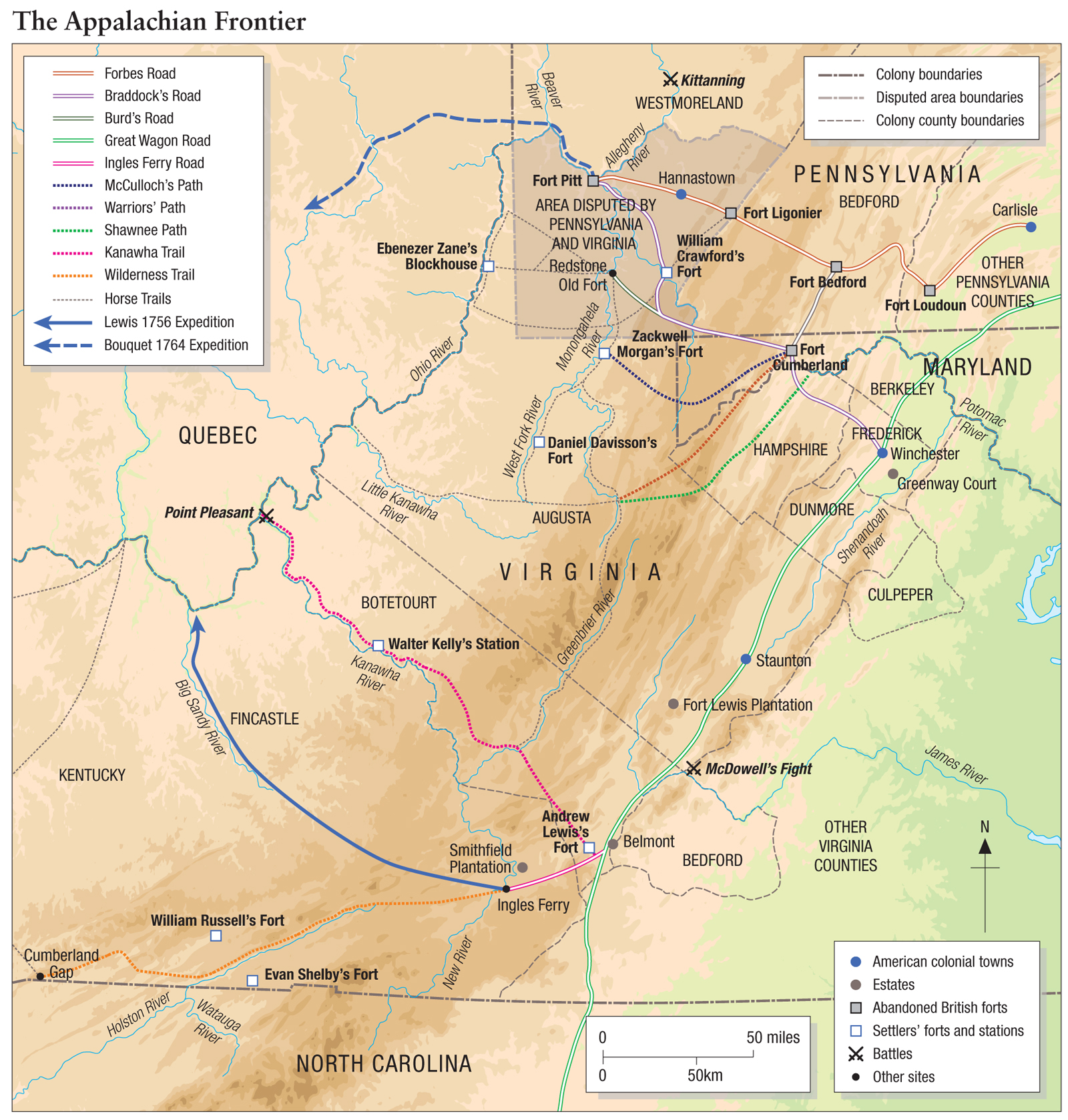

When Indian raiding ended in 1760, the frontier settlers returned to their abandoned homesteads. In 1763, when Pontiac’s warriors appeared with no warning, the flight from the frontier recurred. But after the end of Pontiac’s War, the settlers advanced again. In the north, they followed British military roads built during the French and Indian War. Forbes Road led to Pittsburgh from Carlisle, Pa., and Braddock’s from Winchester, Va. Burd’s Road led on from Braddock’s Road to Redstone Old Fort, an Indian ruin on the Monongahela. To the south, from Braddock’s Road, they followed McCulloch’s Path, a trail blazed by the trader William McCulloch to the Monongahela; and the Warriors’ Path and Shawnee Path, Indian trails that led to what is now Elkins, W. Va. Still farther south, from the Great Wagon Road, they followed the Kanawha Trail, which led toward the Ohio River; and the Ingles Ferry Road and Indian trails that led down the Holston River to Tennessee. By 1774, the westernmost were at frontier strongholds like Ebenezer Zane’s Blockhouse at what is now Wheeling, W. Va.; Joseph Tomlinson’s Fort at Moundsville; Zackwell Morgan’s Fort at Morgantown; Daniel Davisson’s Fort at Clarksburg; Walter Kelly’s Station at Cedar Grove; William Russell’s Fort at Castlewood, Va.; and Evan Shelby’s Fort at Bristol, Tennessee.

Such settlements were in theory in the westernmost counties of the existing colonies. But some on the frontier didn’t know even what colony they were in. In 1772, Shelby and his neighbors, unsure whether they were in Virginia or North Carolina, formed their own government, the Watauga Association.

The western settlers also had little respect for royal authority. Afraid after Pontiac’s War that the Indians soon would attack again, they watched in anger as traders carried munitions west to replenish the Indians’ supplies. In 1765, James Smith, who had lived as an adopted Mingo for four years, organized a band of Pennsylvania settlers to interdict the trade. At the request of the traders, the commandant at British Fort Loudoun sent soldiers who arrested some of them. Smith and 300 men then besieged the fort for two days. On November 11, 1765, the British released the prisoners. When the commandant at Fort Bedford took similar action in 1769, Smith again saved the arrested men. At dawn on September 12, 1769, he and 18 men rushed the fort when the gates opened. After freeing the prisoners, they allowed its 30 soldiers to resume their garrison duties. Fort Bedford, Smith later wrote, “was the first British fort in America that was taken by what they called ‘American rebels.’”

By 1774, about 30,000 settlers lived on the Appalachian frontier in centers of population such as Pittsburgh, which had 40 log cabins; in small fortresses like Doddridge’s Blockhouse near present Washington, Pa.; and on scattered homesteads. In their world, poverty seemed a natural condition of life. Eight-year-old Lewis Doddridge, sent to school in Baltimore in 1777, later wrote, “When I arrived there I was in a new world. I had left the backwoods behind me. I had exchanged its rough manners and poor living for the buildings, plenty and polish of civilized life.”

The photograph shows reconstructed Fort Loudoun at Fort Loudoun State Historic Site in Fort Loudon, Pa. (Courtesy of the Fort Loudon Historical Society)

But on the frontier, freedom also seemed as natural as poverty. In Baltimore, sights that “were viewed with indifference by the whole population of the neighborhood, as matters of course” shocked Doddridge. While returning from school one day, he saw a rich neighbor whip a servant. “I went home with a heavy heart,” he recalled, “and wished myself in the backwoods again.”

From about 1660 until 1701, the Ohio Country had been uninhabited. The conflicts known as the Beaver Wars, in which the Iroquois had battled Indians as far west as the Mississippi River, made the Ohio Country too dangerous for habitation. But after 1701, when the Treaty of Montreal ended the Beaver Wars, the part of the Ohio Country north and west of the Ohio River began to be repopulated.

By 1774, about 20,000 people lived in the area. By birth or adoption, most were members of the Delaware, Kickapoo, Miami, Mingo, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi, or Wyandot Indian tribes. But the Beaver Wars and their aftermath had changed the composition of such tribes forever. Decades of life as refugees among once hostile groups had blurred traditional genetic distinctions. Interaction with French and British traders, soldiers, and captives had left changes that sometimes were visible. There were blond Delawares and black Shawnees. Intermarriage also had altered the nature of tribal loyalties. Many Ohio Indian children had parents who belonged to different tribes. Some Indians cared little for traditional tribal identities and customs. All were fiercely independent.

On the Tuscarawas River, there were Christian Delaware villages, where Indians converted by Moravian missionaries lived much like the colonial settlers. But elsewhere, the Indians passed their years as they had for centuries. In winter they dispersed to hunting lodges and camps, from which the men searched for enough game to avoid starvation. During other seasons, they lived in villages like those of the Shawnee on the Pickaway Plains, a level area on the Scioto River.

Indian villages had bark-covered structures like these at George Rogers Clark Memorial Park, near Springfield, Ohio, the site of the battle of Peckuwe on August 8, 1780. (Author’s photograph)

Visitors to such villages in 1774 first passed large cornfields, where women, children, and slaves labored while the men hunted, warred, or met in councils. Then they saw among the village’s traditional bark-covered structures sights that had been unknown to the Indians’ ancestors. But from some other sights visitors often averted their eyes. There were displays of the scalps of enemies killed by the village’s raiding warriors; 200–300yd-long cleared paths, where captured enemies ran the gauntlet between lines of Indians, trying to evade their captors’ clubs and sticks as their fate was decided. And there were posts where captives were tortured and burned to death.

From the villages, narrow trails passed through the woods in every direction. Some led to trading posts like those of the French trader Peter Loramie on Loramie Creek, and the British trader Richard Butler on the Scioto River, where Indians traded in furs and hides at prices fixed by Sir William Johnson. Others led long distances to the south, the routes of raiding warriors in search of scalps, prisoners, and horses.

Thousands of miles of Indian trails, often invisible to untrained eyes, led through the Ohio Country. Some of the main paths, passable on horseback, have been given modern names such as the Kanawha Trail. This marker in Jackson is on the trail’s route between Lewis’s 3rd and 4th Ohio Camps. (Photograph by Eleanor Essman)

The trails to the northeast led to the villages of the Iroquois in northwestern Pennsylvania and western New York. When the Ohio Indians had begun emigrating to the Ohio Country about 1720, they had settled on land claimed by the Iroquois, whose permission they had received. Then the Iroquois had sent viceroys known as “Half-kings,” to live among the Wyandots and Delaware, men like Shikellany, the father of the Mingo John Logan.

But the power of the Iroquois had waned. When Johnson had asked them to send war parties against the Ohio Indians to end Pontiac’s War, few had responded. By 1768, when the Iroquois sold the area east and south of the Ohio River to the British, the Ohio Indians no longer felt themselves bound by any action of the once powerful confederacy.

The sale at Fort Stanwix most directly affected the Shawnee, who had hunted south of the Ohio for decades. When British surveyors began appearing there in 1770, the alarmed Shawnee sent emissaries to the other Ohio Indians; to the Seneca, with whom Johnson had the least influence; and to the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Creeks in the south. They together, the Shawnee proposed, should renew Pontiac’s War on a larger scale, with attacks on the settlements of every colony from New York to Georgia.

In 1771 and 1772, the Shawnee continued their efforts to create a grand alliance. Croghan, however, and McKee, who in 1771 succeeded him as Johnson’s deputy, were able to thwart their designs. The Ohio Indians, McKee told the Shawnee in 1773, should welcome the Vandalia Colony instead of opposing it. Soon there would be a colonial government at the mouth of the Kanawha. Unlike the distant governments of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, it could not ignore their interests, and would have to regulate settlement effectively.

The Shawnee chiefs found McKee’s argument persuasive. But many warriors were unmoved. Even if they could not attack in tribal war parties, independent groups of warriors could make the land south of the Ohio River an area that colonial surveyors and settlers would find too dangerous to enter.

In 1774, Virginia was by far the most important of Britain’s North American colonies. Its population, about 600,000, was twice that of its nearest rivals, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. Ruled by a royal governor, the colony had 57 counties. In each, the free, adult males constituted the local militia, and selected two county representatives for the colony’s legislature, the House of Burgesses.

On September 25, 1771, John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore, became the new governor of Virginia. The Scottish lord’s star had begun to rise in 1768, when his wife’s sister had married the politically powerful Granville Leveson-Gower, the 2nd Earl Gower. Gower, who later would become the 1st Marquess of Stafford, had obtained the royal appointment for him.

Dunmore soon met the colony’s richest resident, Thomas Fairfax, Baron Fairfax of Cameron. Fairfax had made his fortune investing in land in Virginia. From his new friend, the avaricious Dunmore learned that the best land investments were now in the vast area west of the Appalachians that Virginia claimed as within the colony’s borders.

During the French and Indian War, the colony had raised the Virginia Regiment, a uniformed unit minimally trained to fight with British regulars. To pay the cost of their years of service, Virginia had promised each soldier 50 acres of the western land, and the officers tracts as large as 5,000 acres. When the 1768 sales by the Iroquois and Cherokee opened the area for settlement, Washington asked the Virginia government to honor the promises by authorizing a survey of tracts for veterans between the mouths of the Little Kanawha and Kanawha rivers on the Ohio, and up the Kanawha. In 1770, he and his friend William Crawford, guided by McKee, spent a month surveying the best sites for settlement.

“If that man is not crushed,” Washington wrote of Dunmore after the outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1775, “he will become the most formidable enemy America has.” This 1929 copy by Charles X. Harris of a 1765 portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds depicts Dunmore in the highland dress of the 3rd Regiment of Foot Guards (now the Scots Guards). (Virginia Historical Society)

But there were many other potential settlement sites, especially in the area known as Kentucky. Investments in the most desirable, Dunmore thought, could in time create a fortune beyond the dreams of even the richest London lords and merchants. The Virginia governor began his speculation by acquiring from the colony 100,000 acres at the falls of the Ohio River, the site of present Louisville.

Two obstacles, however, stood in the way of the Virginia governor’s plan to emulate Fairfax. The first was the proposed Vandalia Colony, which would include the land that Dunmore had obtained from Virginia. At his brother-in-law’s request, Gower took action to block the Vandalia Colony project. The second was Pennsylvania. Virginia’s western lands could be reached most easily by the Ohio River, which led southwest from Pittsburgh. Both Pennsylvania and Virginia claimed the area around Pittsburgh as within their borders. Pennsylvania, however, was already administering it.

Previously part of Bedford County, on February 26, 1773, the area had become part of new Westmoreland County, with its seat of government at the village of Hannastown. In the new county, the great landowner Arthur St Clair acted as local agent for Thomas Penn, the governor of Pennsylvania. Crawford was one of its three judges. James Smith was one of its three commissioners, elected to administer the new county’s affairs. Croghan, a leading proponent of the Vandalia Company; his nephew, the ambitious John Connolly; and McKee were other important Westmoreland County figures, and also the prominent Indian traders Richard Butler, John Gibson, and Matthew Elliott.

He must, Dunmore concluded, press his colony’s claim to the Pittsburgh area immediately so that Gower could have the British government decide the dispute in Virginia’s favor. To obtain support for Virginia’s claim from the local population, Dunmore recruited Connolly. He, in turn, enlisted the aid of the able Indian trader Simon Girty, who had lived as a Mingo for eight years.

In December, 1773, Dunmore learned that Gower had succeeded in halting the Vandalia Colony project. He then took bold action to ensure that Virginia’s claim would be addressed quickly. He sent Connolly to Pittsburgh with orders to form a rival Virginia government. As Connolly rode up Braddock’s Road, he stopped at Crawford’s Fort, where he told his host that the Vandalia Colony project had been canceled. “Connolly called on me on his way from Williamsburg,” a puzzled Crawford wrote to Washington, “and tells me that it is now without doubt that the new government is fallen through and that Lord Dunmore is to take charge of so much of this quarter as falls out of Pennsylvania.” When Connolly reached Pittsburgh on January 6, he posted an announcement on the gate of abandoned Fort Pitt that the area now was the Western District of Augusta County, Virginia. As “Captain, Commandant of the Militia of Pittsburgh and its Dependencies,” he ordered the local militiamen to assemble there on January 25.

Dunmore gave little thought to a third possible obstacle. Although war between the Ohio Indians and the settlers had ended in 1764, there since had been incidents in which Indians and settlers had died. Three months before, there had been an especially disturbing one.

On September 25, 1773, Daniel Boone and his friend William Russell, who would lead a company at Point Pleasant, began to assemble a party of 100 settlers, who planned to establish the first settlement in Kentucky. On October 9, Indians attacked 15 of the settlers as they were traveling to join the others. They killed seven, including Boone’s and Russell’s 17-year-old sons, and took the other eight prisoners. The settlers then abandoned the migration and returned home. When three of the Indians’ captives escaped, they identified as one of the attackers the Shawnee warrior Bededee, who had often visited the Boone cabin. Bedeedee, they added, had tortured the wounded Boone and Russell boys before killing them.

When McKee inquired about the incident, the Shawnee chiefs expressed condolences for the deaths, but denied that any Shawnees had been responsible. Although McKee soon learned that Shawnee warriors had been the killers, the response of the chiefs did not surprise him. Like them, he knew that no one could control what individual warriors or settlers might do on the frontier. Such an incident, unless it was overlooked, could easily cause a war.

This Fort Pitt blockhouse, built by Bouquet in 1764, survives near the Fort Pitt Museum in Pittsburgh’s Point State Park. (Courtesy of the Senator John Heinz History Center)