The Virginians were militiamen in two armies, which each had about 1,400 officers and men. Berkeley, Frederick, and Hampshire counties, and the West Augusta District, provided those in the Northern Army. Augusta, Bedford, Botetourt, Culpeper, Dunmore, and Fincastle counties supplied those in the Southern Army.

In theory, the militia of Virginia counties were organized like those of English counties. Each county had a county lieutenant, who served the same function as an English county’s Lord Lieutenant. His militiamen constituted the county regiment, which at full strength had ten companies with 500 men. Its senior officers held permanent commissions as colonels, lieutenant-colonels, and majors. Its junior officers, granted commissions for specific missions, were each company’s captain, lieutenant, and two subalterns, who held the rank of ensign and sergeant.

The costumes of these battle of Point Pleasant re-enactors show the variation in dress of the Virginia militia officers. Eddie Goode (left) wears the uniform of an officer of the Virginia Regiment. Craig Hesson (right), who has a gentleman’s tricorn cocked hat, wears a frontier hunting shirt as a light coat over a gentleman’s collared shirt. (Photograph by Ed Lowe)

In practice, Virginia militia forces were usually collections of companies raised for specific missions. Prominent men offered to captain companies, and persuaded others to serve in their units as junior officers and privates. During their service, the officers and men received daily compensation from the colony, and men left disabled and women left widowed received pensions or payments.

Militia officers varied in their dress. Those who had served in the Virginia Regiment often wore their colorful uniforms. Some, like Col. Charles Lewis, fell at Point Pleasant, where the Indians targeted them. Others dressed exactly like their men, in the broad-brimmed hats, hunting shirts, leggings, and moccasins worn on the frontier.

Frontier militiamen usually carried their own firearms. By 1774, almost all had what first were known as Pennsylvania rifles. Crafted by men like Richard Butler’s father, a gunsmith in Carlisle, Pa., these .32 to .54-cal. weapons were much more accurate than smoothbore muskets. Using powder carried in horns, and balls made from lead bars in molds, most frontiersmen could reload their rifles in about 45 seconds. Marksmen then could hit targets the size of a man at about 200yd.

This rifle was used to defend Bryan’s Station in Lexington, Ky., in 1782 when Indians led by Simon Girty attacked the stronghold. (Kentucky Historical Society, Mrs Jane Cantrill Collection, 1939.371)

For close combat, the frontier militiamen used edged weapons. Most carried tomahawks. All carried knives of various types and shapes, most with large or long blades.

Dunmore’s militiamen varied in their level of experience. Although most were veterans of battles with Indians, some were young volunteers. Fourteen-year-old Pvt. William Stephen died at Point Pleasant. Fifteen-year-old William Russell, who fought in his father’s company, would lead a battalion of Kentucky horsemen at Fallen Timbers and later command the US 17th Infantry Regiment. Sixteen-year-old Martin Wetzel would become a famous frontiersman.

Many of the militiamen would later become celebrated commanders or frontier figures. In the Northern Army, Pvt. John Hardin of Zackwell Morgan’s company, who was wounded at Wakatomica, would lead the Kentucky militia in Gen. Josiah Harmar’s army at the October 19, 1790 battle known as Hardin’s Defeat, and the October 23, 1790 battle of Kekionga. David Williamson of Cresap’s company, who fought at Wakatomica and Seekunk, would lead the militiamen who would kill 96 Christian Delaware at the March 9, 1782 Gnadenhutten Massacre. Simon Kenton of Aston’s company, who fought at Seekunk, would become a legendary frontier figure. Samuel Wells of Capt. John Stephenson’s company would survive Wabash, lead the Kentucky mounted riflemen at Tippecanoe, and later command the US 17th Infantry Regiment. Samuel Mason of the same company would command Fort Henry at Wheeling when it was attacked by Indians in 1777, and later become an Ohio River pirate, terrorizing travelers from a lair at what is now Cave-in-Rock State Park in Illinois. In the Southern Army, James and John Brown of Harrod’s company would become important political figures. Second in command of the Kentucky militia at Wabash, James Brown would later serve as US senator from Louisiana and American ambassador to France. John Brown would be a US senator from Kentucky.

His militia, however, did not impress Dunmore. In correspondence he referred to each of his armies as merely a “body of men.” The officers, he judged, were incapable of imposing “any order or discipline.” The men, he said, were “impressed from their earliest infancy with sentiments and habits very different from those acquired by persons of a similar condition in England.” They were, he concluded, “not much less savage” than the Indians.

The muskets and bayonets of British regulars, the Virginia governor knew, would quickly drive an army of such men from an open field. But Dunmore, whose military experience had been in a royal guards regiment in London, had not seen the massacres of British regulars at Monongahela and Grant’s Defeat. Battles in the western woods were not for men skilled in fighting in regular formations. They were for men who could fight as irregulars.

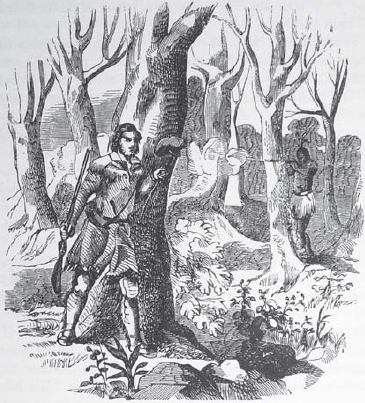

In frontier combat with flintlock rifles, judgment in deciding when to fire and skill in reloading were often as important as marksmanship. Martin Wetzel left behind his 11-year-old brother Lewis at Wetzel’s Fort. Lewis Wetzel, who learned to reload a rifle while sprinting, would become a legend among the Indians, who would call him “the Death Wind.” This engraving from Wills De Haas’s 1851 History of the Early Settlement and Indian Wars of Western Virginia shows Lewis Wetzel tricking an Indian into discharging his musket. (Author’s Collection)

By 1774, a century of sobering experiences in Eastern Europe had taught the most astute European commanders the effectiveness of irregulars against regulars in wooded terrain. The great military theorist Maurice de Saxe had concluded that even the strongest regular army formations should have companies of irregular units to combat enemy irregulars.

What looked to Dunmore like parodies of British regular units were instead assemblies of the best irregulars the British empire could produce. His frontier militiamen all had the highest proficiency in use of their firearms. “A well-grown boy, at the age of twelve or thirteen,” recalled Lewis Doddridge, “was furnished with a small rifle and pouch... Hunting squirrels, turkeys and raccoons soon made him expert with his gun.” They also were masters in use of their edged weapons. “Throwing the tomahawk,” Doddridge remembered, “was another boyish sport... A little experience enabled the boy to measure the distance with his eye, when walking through the woods, and strike a tree with his tomahawk in any way he chose.”

Combat by irregular forces, which was very difficult for commanders to visualize, required the keenest judgment. Saxe therefore had urged generals to choose their best junior officers as leaders of their irregular units. The quality of Dunmore’s and Lewis’s commanders was especially critical because of the nature of the men they would lead.

A mistake by an officer commanding the aggressively independent Virginia frontiersmen might easily lead to mutiny or mass desertion. During the Wakatomica expedition, Major Angus McDonald learned how quickly an officer could lose such men’s respect. The conduct of 18-year-old Pvt. Abraham Thomas in cleaning a rifle barrel annoyed him. McDonald, Thomas remembered, “came towards me swearing, with an uplifted cane, threatening to strike. I instantly arose on my feet with my rifle barrel in my hand and stood in a position of defense. We looked each other in the eye for some time. At last he dropped his cane and walked off, while the whole troop laughed.”

Dunmore’s and Lewis’s militiamen would also battle the Ohio Indians. The Virginians might aspire to equal, but could not hope to surpass, their skill in conducting irregular operations. “The advantageous way they have of fighting in the woods,” Washington wrote, “their cunning and craft, are not to be equalled, nor their activity and indefatigable sufferings.”

Dunmore, who never saw his militiamen in combat, believed that their only strength lay in numbers. Far greater British commanders would see them at Saratoga and Vincennes, King’s Mountain and Cowpens. There they would learn what such men could do when led by officers like Dunmore’s Capts. Daniel Morgan and George Rogers Clark, and Lewis’s Lts. Isaac Shelby and John Sevier.

This portrait by an unknown artist depicts Angus McDonald Forty-seven in 1774, he lived at Glengarry, his estate near Winchester. (Author’s collection)

The Indian army included about 425 Shawnee warriors. The Shawnee, whose name meant “the southern people,” were closely related to the Kickapoo, who spoke an almost identical language. For centuries, they had lived scattered across the eastern United States. But around 1725, they had begun to settle in Ohio, where in 1774 most lived.

The Shawnee had five subgroups: the Chalawgatha (also spelled Chillicothe), the Mequashake, the Thawakila, the Kispoko, and the Peckuwe (also spelled Piqua). Each claimed certain traditional rights within the tribe. The Chalawgatha and Thawakila, for example, contended that only men from their subgroups should serve as the tribe’s principal chiefs. The Kispoko made similar claims about war leaders.

About 150 Mingos fought with the Shawnees. The Mingos were a product of the Beaver Wars, when the tribes of the Iroquois confederacy had attempted to incorporate thousands of defeated enemies. Many descendants of captives, and of Caughnawagas, Catholic converts who had separated from the Mohawks, ultimately moved to Ohio, where they became known as the Mingo.

About 125 Delaware, Kickapoo, Miami, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Wyandot volunteers constituted the remainder of the army. Although the leaders of those tribes had rejected appeals to join the war against the Virginians, individual warriors answered the call. Family ties or sympathy with the Shawnee and Mingo cause prompted some. Others just wanted scalps or plunder.

Indian warriors usually fought in units of about 20, from which some were detached to hunt for the unit’s food. Many who fought at Point Pleasant were descendants of traders or captives, or had themselves been captured and adopted. Private Thomas Collet of Skidmore’s company found the body of his dead brother, the adopted Shawnee George Collett, on the field at Point Pleasant.

Indian commanders and warriors dressed identically. Most wore only a loincloth, leggings and moccasins. Some also wore hunting shirts like those of the Virginians. With feathers or porcupine quills rising from their hair, dangling nose rings and earrings, and faces painted in stunning designs, they appeared terrifying in battle.

The Indians used firearms of different calibers, including smoothbore muskets; rifles; and fusils, small muskets usually used for hunting. Many carried weapons obtained in battles and raids, often the .75-cal. British Long Pattern Musket. The Virginians’ rifles gave them an advantage in accuracy in exchanges of gunfire beyond about 50yd. The Indians, however, who preferred smoothbore weapons, had an offsetting advantage. They rarely fired single projectiles from their weapons. Most used rounds of one large ball, and three smaller balls of as little as .25 caliber.

Many Indians also carried bows, usually from 4 to 6ft long, and arrows tipped with scrap metal or stone. Such easily portable weapons had a range of more than 100yd, and were as accurate as smoothbore muskets. Indians used them if they lacked firearms or had exhausted their supplies of powder or balls. For close combat the Indians used tomahawks, war clubs, and knives.

This firelock from an Indian musket, found in 2010 at the site of Grenadier Squaw’s Town, is probably from a weapon used at Point Pleasant. (Author’s photograph)

Although Indian women were not trained to fight in wars, Cornstalk’s sister Nonhelema joined the outnumbered Indian army that fought at Point Pleasant. Described by contemporaries as several inches taller than six feet, she was called by the Virginians the Grenadier Squaw. She left behind at her village, Grenadier Squaw’s Town, her 11-year-old son Tamenatha, whose father was Richard Butler.

The Indians warred with the American colonists just as they fought one another. Tribes were usually at war with other tribes. In 1774, the Miami were at war with the Cherokee, the Ojibwe with the Sioux, the Iroquois and Mingo with the Catawba, and all of the Ohio Indians with the Chickasaws of Mississippi.

Indian wars were unrestrained conflicts, in which the age or sex of enemies was disregarded, and whole tribes risked extermination. In 1730, the Fox of Wisconsin almost vanished in a war with the French and the Ohio Indians. When they tried to escape their enemies by migrating to Pennsylvania, an army of Ohio Indians trapped 800 near what is now Arrowsmith, Ill. On September 9, 1730, they killed 600 Fox men, women, and children, and captured the others.

In Indian war, prisoners became the property of the warriors who took them. Unless adopted or enslaved, adult males, and sometimes females, might be tortured to death and even ritually eaten. Children were usually adopted.

Because Indian wars were between small groups, Indian commanders sought above all to avoid casualties. Any trick or tactic that would allow enemies to be killed or captured without risk was used. They preferred raids and massacres to battles, and ambushes to engagements in which enemies could fight on even terms.

The Indians’ way of war created the impression that they were treacherous and cruel. Their frequent retreats in battle also left some with the mistaken belief that they were cowardly. “They will not stand cutting like the highlanders or other British troops,” wrote James Smith, “but this proceeds from a compliance with their rules of war rather than cowardice.”

The Indians’ behavior also appeared undisciplined. Before and after combat, they were often beyond the power of anyone to command. But in battle, Smith wrote, they were disciplined masters of the small-unit maneuvers that produced victories in battles in the western woods.

Indian boys, who had learned at an early age to survive alone in the woods, and to use the weapons they would carry in combat, began at 12 to learn such maneuvers. While living as a Mingo, Smith had watched them practice encircling areas of various sizes to surround enemies, and forming hollow squares for defense. He had seen a mile-wide line of widely dispersed warriors advance through the woods indefinitely without losing order, with each man following the lead of the warrior to his right. Such maneuvers, Smith concluded, required a subtler discipline than that known to British or colonial soldiers. “It is easier,” he wrote, “to learn to move and act in concert in close order in the open plain than to act in concert in scattered order in the woods.” In combat in wooded terrain, he judged, the Indians were “the best disciplined troops in the known world.”

During the French and Indian War, the Indians told Smith, the ratio of colonial to Indian casualties was about 50:1. During Pontiac’s War, it fell to about 10:1. In Lord Dunmore’s War, Smith thought, the ratio was about 3:1. “None will suppose we had a contemptible enemy,” Capt. John Stuart wrote many years later, “who has any knowledge of the exploits performed by them... They are now dwindled to insignificance ... and futurity will not easily perceive the prowess of which they were possessed.”

This monument at Logan Elm State Memorial, near Circleville, Ohio, commemorates Nonhelema. (Author’s photograph)

Commander killed or mortally wounded (K)

Commander wounded (W)

Commander not present at battle (NP)

Colonel Andrew Lewis, County Lieutenant of Botetourt County, Commander

Major Thomas Posey, Quartermaster General

AUGUSTA COUNTY REGIMENT (12 COS.) (560)

Colonel Charles Lewis, County Lieutenant of Augusta County, Commander (K)

Company of Capt. George Matthews (65)

Company of Capt. Alexander McClanahan (65)

Company of Capt. George Moffat (55)

Company of Capt. John Dickinson (W) (25)

Company of Capt. Samuel McDowell (50)

Company of Capt. Benjamin Harrison (45)

Company of Capt. Andrew Lockridge (30)

Company of Capt. John Skidmore (W) (35)

Company of Capt. Samuel Wilson (K) (25)

Company of Capt. Joseph Haynes (60)

Company of Capt. John Lewis (60)

Company of Capt. William Nalle (45)

BOTETOURT COUNTY REGIMENT (11 COS.) (510) 2

Colonel William Fleming, Colonel of the Botetourt County Regiment, Commander (W)

Major William Ingles, Quartermaster General

Pvt. John Todd, Aide-de-camp

Company of Capt. John Lewis (70)

Company of Capt. Philip Love (40)

Company of Capt. John Murray (K) (55)

Company of Capt. John Stuart (40)

Company of Capt. Robert McClanahan (K) (30)

Company of Capt. Henry Pauling (50)

Combined Company of Capt. Matthew Arbuckle and Capt. James Ward (65) 3

Capt. Matthew Arbuckle, Commander

Capt. James Ward, Second in command (K)

Bedford County Company of Capt. Thomas Buford (K) (50)

Field’s Culpeper and Dunmore County Companies (3 cos.) (110)

Colonel John Field, Colonel of the Culpeper County Regiment, Commander (K)

Culpeper County Company of Capt. James Kirtley (40)

Culpeper County Company of Capt. William Chapman (35)

NOT PRESENT AT BATTLE 4

Dunmore County Company of Capt. George Slaughter (35)

FINCASTLE COUNTY REGIMENT (8 COS.) (285) 5

Colonel William Preston, County Lieutenant of Fincastle County, Commander (NP)

Colonel William Christian, Colonel of Fincastle County Regiment, Acting Commander

PRESENT AT BATTLE 6

Company of Capt. William Russell (45)

Watauga Association Company of Capt. Evan Shelby (50)

NOT PRESENT AT BATTLE 7

Company of Capt. William Robertson (35)

Company of Capt. Walter Crockett (30)

Company of Capt. William Campbell (30)

Company of Capt. William Herbert (25)

Company of Capt. John Floyd (45)

Kentucky Pioneer Company of Capt. James Harrod (25)

SHAWNEE (425)

Cornstalk, Silver Heels, Nimwha, Black Fish, Blue Jacket, Puckeshinwa, Black Snake, Captain Johnny, Black Hoof, Commanders

MINGO (150)

Pluggy, Commander

OTHER INDIANS (125)

Unknown commanders, probably including the Delaware Buckongahelas

1. Approximately 1,365 officers and men in 31 companies advanced from Camp Union. About 1,130 in 24 companies were at Point Pleasant. The numbers are estimates based on company numbers recorded on different dates.

2. The Botetourt County Regiment included four independent companies from other counties. They were a Bedford County company and three companies led by Col. John Field. Those included two Culpeper County companies and a Dunmore County company led by Field’s son-in-law George Slaughter.

3. Arbuckle’s company included a small company earlier led by Capt. James Ward.

4. This company arrived at the battlefield on October 14, 1774.

5. The Fincastle County Regiment included two independent companies, Shelby’s Watauga Association Company and Floyd’s Kentucky Pioneers.

6. These companies were detached to the Botetourt County Regiment at the time of the battle.

7. These companies arrived at the battlefield after fighting had ended.

8. The total and numbers by tribal units are estimates. The Delaware chief White Eyes told Dunmore that 700 Indians had advanced toward Point Pleasant. Fleming estimated their numbers at the battle at 700–800 and Isaac Shelby at 800–1,000.