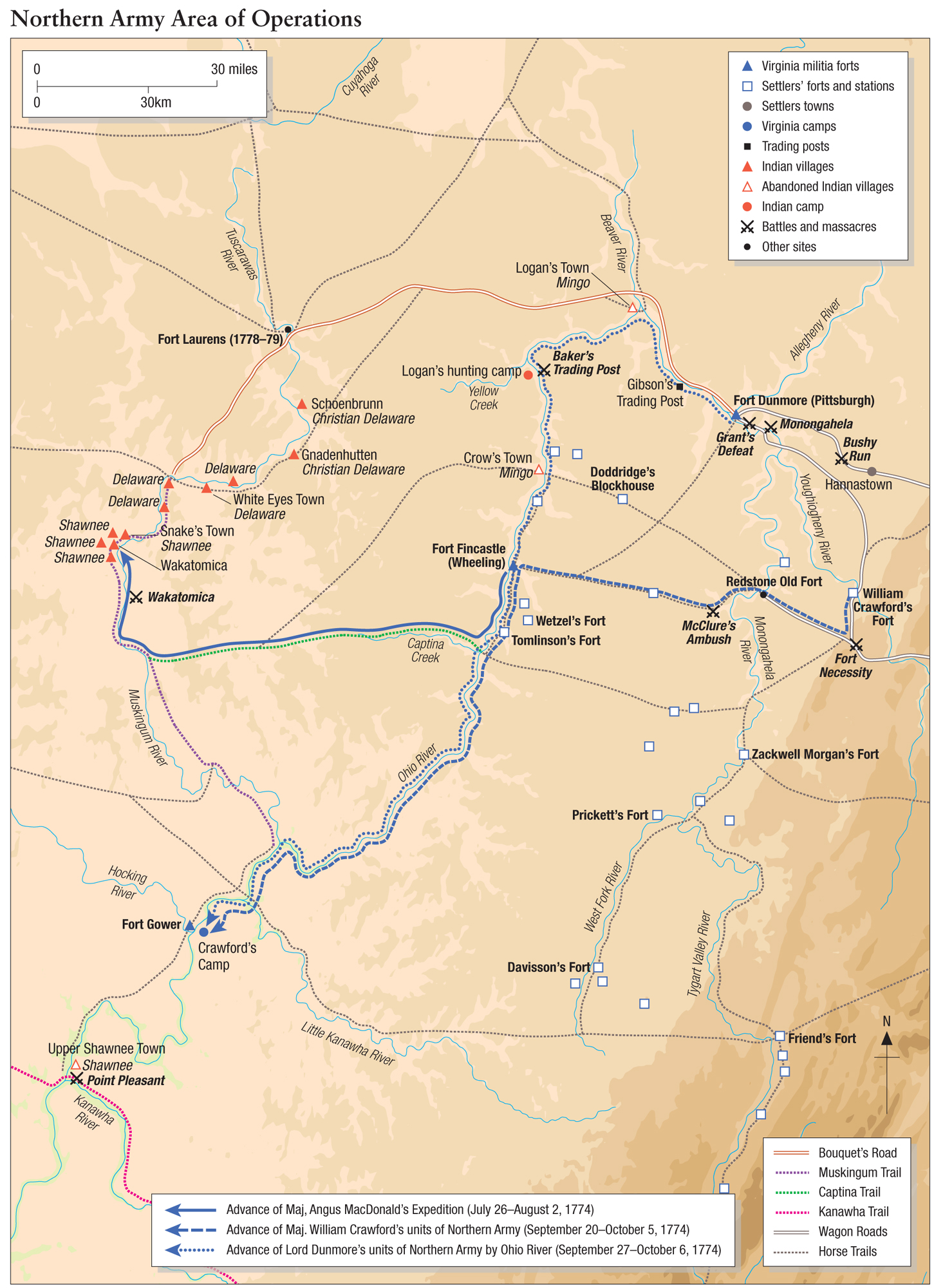

As Connolly waited for a response to his assertion of authority in Pittsburgh, others planned western surveying expeditions in the spring. In Winchester, Fairfax’s friend Angus McDonald, a major in the Frederick County militia, intended to survey land on the Ohio River. John Field, colonel of the Culpeper County militia, was to lead a surveying party down the Kanawha River. William Preston, the County Lieutenant of Fincastle County, planned to send the 23-year-old frontiersman John Floyd on a similar expedition to Kentucky.

Three other young frontiersmen planned to lead men down the Ohio River to found the first settlements in Kentucky. Alarmed by the fate of Boone’s and Russell’s settlers, they would go without their families to claim land and build cabins. Twenty-eight-year-old James Harrod was to guide the first party from Tomlinson’s Fort. Thomas Cresap’s 32-year-old son Michael was to lead another from Pittsburgh to the mouth of the Muskingum River. There, at present Williamstown, W. Va., some were to settle while others followed him to Kentucky. Twenty-two-year-old George Rogers Clark was to go to the mouth of the Little Kanawha. There, at present-day Parkersburg, W, Va., settlers would arrive to form another party to go to Kentucky.

The practices of the Indian shamans were ancient. Centuries before Lewis halted at his 4th Ohio Camp, these figures had been carved in a rock 4 miles to the north. They probably depict details of a famous shaman’s vision at the site, now Leo Petroglyph State Memorial in Leo. (Photograph by Tom Walton)

On January 24, the sheriff of Westmoreland County arrested Connolly for his actions. When Dunmore’s agent promised to appear for trial in Hannastown on April 6, the sheriff released him. Connolly then fled back to Virginia.

In March, Harrod’s party went down the Ohio. Cresap’s party soon followed. By March 28, men in canoes were arriving daily at Clark’s camp. That day, Connolly returned to Pittsburgh. Men recruited by Girty then occupied abandoned Fort Pitt, which Connolly renamed Fort Dunmore. As Connolly began establishing the new West Augusta District of Virginia, the British at last responded to the Boston Tea Party. On March 31, the government in London announced that British soldiers and ships would close the port of Boston indefinitely on June 2.

After his arrest, Connolly wrote this letter to George Washington from Pittsburgh. “I have been committed to jail,” he wrote on February 1, 1774, “for denying the jurisdiction of Pennsylvania at Pittsburgh and attempting to act under a commission from Virginia.” (Library of Congress, Manuscript Division)

On April 6, Connolly arrived for his trial at the Hannastown tavern that would serve as the Westmoreland County courthouse. It was to be the first proceeding in the first court to open west of the Appalachians. But the assembled judges and dignitaries received a surprise. Connolly brought with him Girty and 150 men.

After threatening to arrest the judges, Dunmore’s agent dispersed the Pennsylvanians. On April 8, Crawford, on behalf of the judges, and Smith, on behalf of the Westmoreland County commissioners, wrote to Governor Penn asking for immediate help. Soon, they hoped, hundreds of Bedford County militiamen would arrive to restore order.

On April 9, when Floyd and his surveyors left for Kentucky, 13 men from a hunting party arrived at Clark’s camp. When they reported that Indians had killed three of their companions, the 80 settlers at the camp demanded that Clark lead them in an attack on Horsehead Bottom, an Indian village further down the Ohio.

Clark, who wanted a more experienced commander to lead the expedition, sent a messenger to Cresap, who was 15 miles upriver. “To our astonishment,” Clark later wrote, “our intended general was the person who dissuaded us from the enterprise, alleging that the circumstances were suspicious but that there was no certainty of war.” They all, Cresap, advised, should return to Wheeling to get more information. “The measure,” Clark remembered, was adopted. “In two hours we were underway.”

When McDonald, whose party was surveying farther down the Ohio, learned of their action, he too led his men back to Pittsburgh. There Connolly was recruiting militiamen to form a force to resist the expected Pennsylvania invaders. To his dismay, he found that few frontiersmen were willing to join an army that would battle Pennsylvanians. There was, however, an enemy they would gladly fight, the Ohio Indians.

Connolly learned from McKee that a visiting Shawnee had reported that Indian warriors were talking of attacking settlers near Pittsburgh. McKee, who had heard such stories before, was unconcerned. But then, on April 16, Indians at the mouth of the Beaver River fired on three men in a canoe carrying supplies to Richard Butler’s trading post, killing two. The attackers, Butler later judged, probably had been Cherokees raiding in Ohio.

By the time the survivor reached Pittsburgh, Connolly had learned that Cresap’s and Clark’s men were in Wheeling. On April 21, he sent a letter to Cresap. Connolly, Clark remembered, asked the men to stay in Wheeling until he could determine whether there was an Indian war. On April 26, he sent Cresap a second letter. “War,” Connolly wrote, “is inevitable.”

No one in Wheeling had any doubt what that meant. When the Indians decided to go to war, they did not send formal declarations to their enemies. Soon there would be deceit, as at Archibald Clendennin’s house at what is now Lewisburg, Va. On June 27, 1763, an apparently friendly Shawnee, invited to eat, had soon been joined by another, and then another, until there were 18. They had then killed the men, and taken the women and children. And there would be surprise, as at Enoch Brown’s schoolhouse near present Greencastle, Pa. On July 27, 1764, four Delawares had entered the classroom where Brown was teaching 15 children. After killing Brown and nine of the children, they scalped two others, and took the remaining four back to Ohio. The receipt of Cresap’s letter, Clark remembered, was “the epoch of open hostilities with the Indians.”

On July 13, 1782, British rangers and Indians led by Girty would burn Hannastown. This reconstruction of the tavern that served as the Westmoreland County Courthouse is at Historic Hanna’s Town, a reconstruction of the village at the original site, near Greensburg, Pa. (Photograph by Louise Tilzey-Bates – Westmoreland Heritage)

During Pontiac’s War, warriors from all of the Ohio Indian tribes had attacked the frontier settlements. The Virginians at Wheeling assumed that warriors from all would do so again. On April 27, they sighted a canoe with three Indians passing on the Ohio. After pursuing it 15 miles to the mouth of Captina Creek, they killed one of the paddlers.

Forty-two miles up the Ohio from Wheeling, there were more Indians. At the mouth of Yellow Creek, opposite Joshua Baker’s trading post, the Mingo John Logan had a hunting camp. On April 28, Cresap’s men began marching up the river to attack Logan’s camp. But Clark, who been at the camp a month before, persuaded Cresap and the others that the Indians there were not hostile.

By then, however, news of the war had spread beyond Wheeling. On April 30, 32 settlers attacked Logan’s Indians. They killed eight visiting the trading post, and another two as they fled across the river. The dead included Logan’s mother, brother, sister Koonay, and Koonay’s two-month-old daughter, whose father was the trader John Gibson.

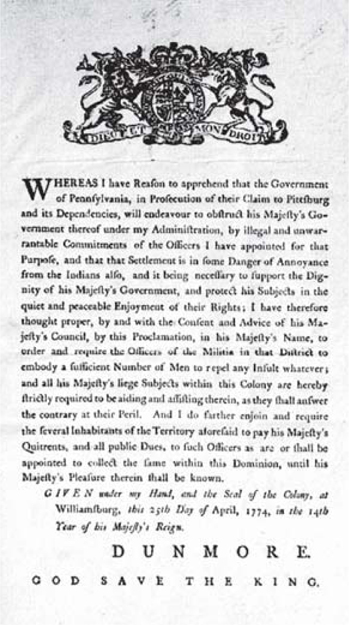

On May 5, Connolly posted a proclamation in Pittsburgh that Dunmore had sent from Williamsburg on April 25. The West Augusta District, it said, was threatened by attack from both Pennsylvanians and Indians. The district’s militia officers, the governor ordered, were to raise forces that would be large enough to repel any assaults by either.

This sketch in crayon by an anonymous artist depicts John Connolly. (Courtesy of the Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.)

When a horrified McKee learned of the massacre at Baker’s trading post. he dispatched messages to the main Ohio Indian chiefs. He had acted quickly, he wrote to Johnson on May 5, “to convince those people to whom they were to be delivered of our sincerity, and that we did not coun tenance those misdemeanors.” But everywhere near the Ohio River, settlers decided not to await the Indians’ response. “The whole country,” Crawford wrote to Washington on May 8, “is vacated as far as the Monongahela.”

News of the massacre spread quickly among the Mingos, who thought that the killers had been Cresap’s men. Pluggy, the leading Mingo chief, was furious. Logan, who had refused to fight in Pontiac’s War, had since been a voice for peace in Indian councils. But in the French and Indian War he had been a merciless raider. Now he recruited 20 warriors to follow him in seeking revenge. Soon they left for the first of four raids, from which they would return with more than 30 scalps and many prisoners.

Dunmore’s annexation of Westmoreland County had attracted little interest in the Virginia House of Burgesses, where attention was focused on the conflict with Britain. The news that the British would close the port of Boston had been followed by another infuriating report. They now had decided to transfer the area north of the Ohio River from Virginia to Quebec. The house had voted to send Washington, Patrick Henry, and another Virginian to Philadelphia, to what would be called the Continental Congress. There, on September 5, representatives from the colonies would begin considering joint action to force Britain to repeal its intolerable legislation.

This monument near Yellow Creek, Ohio, commemorates the site of John Logan’s hunting camp. (Photograph by Dale Benington)

On May 13, Dunmore presented to the burgesses a report he had received from Connolly the day before. The frontier, it said, was aflame. The House of Burgesses, he urged, should fund an army of Virginia militiamen to conduct offensive operations against the Indians. The following day, the house rejected the request. Existing legislation allowed the governor to raise militia units to defend the frontier counties. That, the burgesses responded, should be adequate. On May 24, the house proclaimed June 2 a day of mourning in Virginia. On May 26, Dunmore dissolved the body.

At Pittsburgh, McKee received almost daily messages from Indian chiefs saying that their warriors were not attacking settlers. But all across the frontier, the talk was of raids and massacres. “The Delaware,” wrote a man in Bedford on May 30, “say that they will not go to war, but there is no dependence in them. We expect every day to hear of their striking in some quarter... The Shawnee themselves say that they have nothing against Pennsylvania, but only Virginia; but we may depend, as soon as they strike the Virginians, they will also fall on us.”

Dunmore’s April 25, 1774 Proclamation. (Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division)

Five hundred miles from Bedford, British warships and soldiers began on to enforce the closure of Boston harbor June 2. That day Logan led his raiders across the Ohio River. On June 7, Connolly reported to Dunmore that he was raising militia companies, would build a fort in Wheeling and then lead a militia army from Wheeling against Indian villages in Ohio.

As McKee’s despair grew, Connolly daily became more jubilant. Croghan, after learning of the collapse of the Vandalia County project, had become a reluctant supporter of his nephew’s government. Penn, who had little interest in the frontier, had rejected Crawford’s and Smith’s pleas for aid. Crawford, disgusted by Penn’s response, had offered to raise companies for Connolly’s militia army. Smith, who had been asked to lead the defense of the Pennsylvania settlers against Indian raiders, was busy recruiting Bedford County companies to patrol the woods. St Clair, for whom Connolly had issued an arrest warrant, was considering flight to Bedford County.

In 1774, Sgt. Isaac, and Pvts. Jacob and Josiah Prickett, of Capt. Zackwell Morgan’s company, built Prickett’s Fort as a refuge for Monongahela River settlers. This reproduction is at the site, now Prickett’s Fort State Park near Fairmount, W. Va. (Courtesy of Prickett’s Fort Memorial Foundation)

On June 10, Dunmore wrote to the lieutenants of Virginia’s frontier counties, urging them to summon militia companies to defend against raids. He also recommended that the southwestern county lieutenants should send men to build a fort like Connolly’s at the mouth of the Kanawha River. That same day, McKee wrote a letter appealing to Johnson. An Indian war, he said, could be avoided only if Connolly was removed. The British government, he pled, must either restore the area around Pittsburgh to Pennsylvania, or send soldiers to take control of the region for the crown while the colonies’ rival claims were adjudicated.

In response to Connolly’s call for volunteers, the trader John Gibson and frontiersman George Aston raised companies among the Ohio River settlers. Girty, appointed a lieutenant in Aston’s unit, persuaded his 19-year-old friend Simon Kenton to enlist as a private. Francis McClure assembled another company of Monongahela settlers. But as McClure’s company marched to join Connolly at Wheeling, four of Logan’s raiders ambushed it about 10 miles southwest of Redstone. There, on June 11, it lost its captain at McClure’s Ambush.

The chances for peace, McKee knew, were rapidly vanishing. On June 14, a Delaware visiting Pittsburgh was fired on while talking to him. Four days later, as Butler was returning to Pittsburgh with a delegation of Shawnee chiefs, McKee learned that Connolly had ordered a company of 40 militiamen to arrest them when they arrived. He diverted Butler and the Shawnees to Croghan’s cabin, where they hid. But when the Shawnees left to return to Ohio, militiamen shot Cornstalk’s brother Silver Heels. Badly wounded, he escaped with the aid of Butler, who told him that the attack had been by Virginians, not Pennsylvanians.

Alarmed at the prospect of a war, the Iroquois sent the Seneca chief Guyasuta to urge the Ohio tribes to remain peaceful. To McKee’s relief, the widely respected Delaware chief White Eyes, protector of the Christian Delaware, joined him. But after the attack on Silver Heels, White Eyes reported, 40 Shawnees had left their villages to raid the settlements.

When Connolly realized that he could not raise in the West Augusta District a militia force large enough to invade Ohio, he turned to Dunmore for aid. The Virginia governor asked McDonald to recruit volunteers in Berkeley, Frederick, and Hampshire counties, and to lead them and Connolly’s men in a punitive expedition against Wakatomica and other Shawnee villages on the Muskingum River. Dunmore also offered a commission as a Virginia militia captain to Cresap, who promised to recruit men for the expedition in Maryland.

In response to Dunmore’s letter of June 10, Preston asked Boone on June 20 to go to Kentucky to recall Floyd’s surveyors and Harrod’s settlers. The Fincastle, Botetourt, and Augusta county lieutenants then raised militia companies to patrol the woods around their settlements. In the most likely area of Indian attack, the Kanawha, New, and Greenbrier river settlements across the western range of the Appalachians, three militia companies began searching for signs of raiders. On June 27, Indians ambushed Capt. John Dickinson’s company, killing one and wounding two at Dickinson’s Fight.

In 1778, Alexander McKee would flee Pittsburgh with Simon Girty and the trader Matthew Elliott to fight with the British during the Revolutionary War. For the next 17 years he would be the chief British agent among the Ohio Indians, and also prosper as a trader. This 1760 telescope, which belonged to McKee, is displayed at Fort Malden National Historic Site in Amhersburg, Ontario. (Photograph by Alexandra Deckerf)

Field and his son Ezekiel were at Kelly’s Station when Indians struck. Although they killed Kelly and captured Ezekiel, Field escaped, wearing only a shirt. Captain John Stuart, who led one of the militia companies defending the New and Greenbrier river settlements, met him fleeing on the Kanawha Trail. “His body,” Stuart recalled, “was grievously lacerated with briars and brush, and worn down with fatigue and cold, having run in that condition from the Kanahway, upwards of eighty miles through the woods.”

In response to McDonald’s request, several famous captains, including Daniel Morgan, James Wood, John Tipton, and William Linn, raised Berkeley, Frederick, and Hampshire County companies. By July 10, they were marching west on Braddock’s Road. That day Dunmore left Williamsburg for Greenway Court, Fairfax’s estate near Winchester, from which he would manage the frontier war. The following day, signs of Indian raiders were found near Hannastown.

As the Mingos and Shawnees raided, McKee, Guyasuta, and White Eyes worked to keep the other Ohio tribes from joining them. Even Logan, who thought Cresap’s men had killed his relatives, tried to limit the scope of hostilities. After killing the settler John Roberts and his wife and children, he left a war club at their cabin. Wrapped around it was a letter, written for him by the captive William Robinson in ink made from gunpowder. “Captain Cresap – What did you kill my people on Yellow Creek for?” it began. “I have been three times to war since; but the Indians are not angry, only myself. Captain John Logan. July 21, 1774,” the letter ended.

Soon the area around Ebenezer Zane’s blockhouse in Wheeling was crowded. Connolly arrived to build his fort, which he would name Fort Fincastle. McDonald appeared with his men, and then Cresap and Clark, with an oversized company. When Crawford arrived with his men, the expedition against Wakatomica would begin.

About 400 men would advance by canoes down the Ohio to the mouth of Captina Creek. They then would follow the Captina Trail and the Muskingum Trail to Wakatomica, Snake’s Town, and three smaller Shawnee villages on the Muskingum River. They would have no packhorses, and would have only the food they could carry with them to eat. But they could leave food with the canoes. If they could advance and return in long enough daily marches, they would find supplies waiting for them before the food they carried was exhausted.

At Greenway Court, Dunmore learned that a hundred Shawnee warriors in eight war parties were now raiding the settlements. The expansion of the war, he concluded, presented an opportunity. He would, he decided, lead an army much larger than McDonald’s into Ohio himself. With it, he would demonstrate to the Indians and Pennsylvanians alike Virginia’s dominion over the frontier. He would force the Mingos and Shawnees to sue for peace and return prisoners at a council like Bouquet’s ten years before. On July 24, he issued a flurry of orders. Adam Stephen, the Berkeley County Lieutenant, was to raise a regiment and march to Greenway Court. The Frederick and Hampshire county lieutenants were to dispatch with him additional companies beyond those already with McDonald. Preston and the Augusta and Botetourt county lieutenants were to raise regiments and march to the mouth of the Kanawha River.

Greenway Court was about 4 miles southeast of Winchester. Fairfax’s land office still stands at the site. (Courtesy Preservation Virginia)

On July 25, Crawford arrived with his recruits, who would remain in Wheeling to finish Fort Fincastle, while McDonald’s men attacked Wakatomica. On July 26, canoes carried the Virginians to the mouth of Captina Creek. After reaching the Muskingum River, they marched upstream. To avoid detection, they then left the Muskingum Trail and moved up the east side of the river.

But on August 2 they saw Indians, and discovered along their route a prepared ambush site. Late that afternoon, they entered a swampy area 6 miles south of Wakatomica. Marching in three columns, the Virginians found that only a single, narrow path led through the swamp to high ground beyond. When the first Virginians emerged from the path and began climbing up toward the high ground, about 40 Indians attacked. For a half-hour, the Virginians struggled forward through the swamp under fire, and then moved right and left to form a line beyond it. When there finally were enough, Cresap led them forward and drove the Shawnees from the field. Two Virginians were killed. Linn and Pvt. John Hardin, who would become a famous Kentucky militia leader, were among the five wounded.

Leading the Virginians who had crossed the swamp, Cresap pursued the fleeing Indians up the Muskingum to opposite the Shawnee towns. McDonald and the rest of the army arrived to join them at camps across the river from Wakatomica and Snake’s Town. That night, Indian emissaries appeared, saying that the Shawnees wanted peace and would return two women taken during raids. As they talked, the Indians at the villages fled with their prisoners, leaving behind only a few warriors.

Cresap, who expected a Shawnee attack the following morning, decided to move first. Two hours before dawn on August 3, his men crossed the Muskingum River and entered Wakatomica. There a warrior died and a Virginian was wounded before the last Indians fled. Finding the other villages empty, the Virginians burned them and the surrounding cornfields.

Many Indians preferred war clubs to tomahawks as weapons in close combat. The clubs often had wooden spikes or were studded with pieces of metal. (Jeff Dearth Collection)

Their food, how ever, was now almost exhausted. With their remaining supply, and a cow and some almost inedible corn found at the villages, the Virginians started back to the Ohio River. “The men,” Thomas remembered, “became exceedingly famished on this march, and I myself, being so young, was so weak that I could no longer carry anything on my person.” At last, the starving men reached the river, feasted on the food left in the canoes, and returned upriver to Wheeling.

Connolly named the fort in Wheeling after another of Dunmore’s titles, Viscount Fincastle. In 1776, when Virginia’s new state legislature would elect Patrick Henry the state’s first governor, Fort Fincastle would be renamed Fort Henry. During the Revolutionary War, it would be attacked by Indians and British rangers on September 1, 1777, and be besieged from September 11 to 13, 1782. This marker in downtown Wheeling is at the site. (Photograph by Rick Robol)

When McDonald returned to Wheeling, he found new orders from Dunmore. He was to join the Virginia governor at Greenway Court, where men were gathering for Dunmore’s campaign. The men he had led to Wakatomica were to march to Redstone, where the packhorses and cattle for the campaign would be collected. The other militiamen were to remain in Wheeling or Pittsburgh. Crawford was to recruit more men.

As McDonald rode east, other commanders were meeting 250 miles to the south. In 1732, John Lewis and his family had left Ireland to become the first settlers in the upper Shenandoah Valley. The town of Staunton had grown up around his fort, Fort Lewis. In 1756, his son Andrew had built another Fort Lewis, in present Salem, Va. Now the County Lieutenant of Botetourt County, Col. Andrew Lewis would command Dunmore’s Southern Army.

Two men soon joined Lewis. William Fleming, the colonel of Lewis’s Botetourt County Regiment, arrived from Belmont, his home in what would later become Roanoke. Next came Lewis’s younger brother Col. Charles Lewis. In 1750 he had built his own stronghold, which was known as Fort Lewis Plantation. He was now the County Lieutenant of Augusta County.

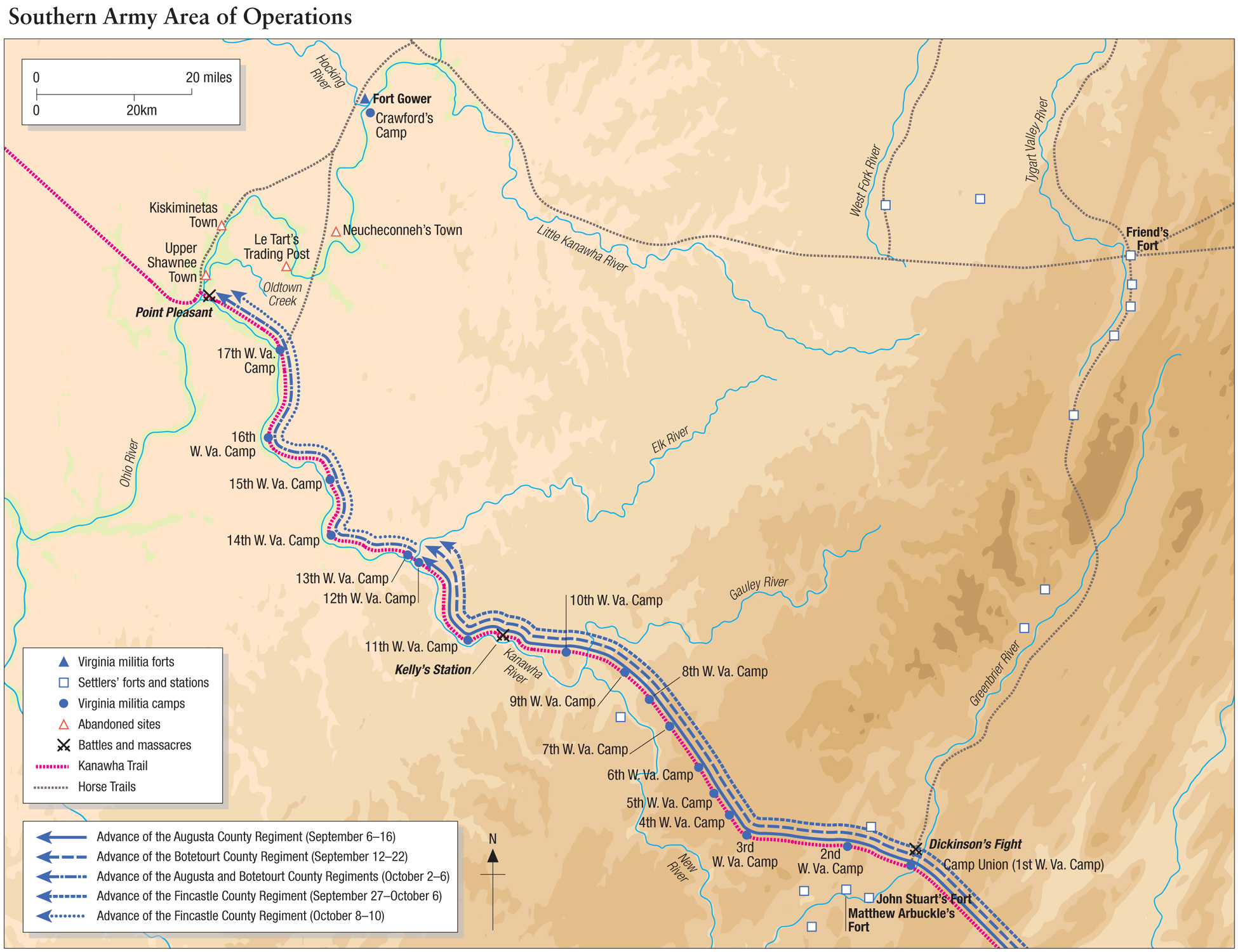

On August 12, the Lewis brothers and Fleming reached Preston’s Smithfield Plantation, where they met with Preston and William Christian, colonel of the Fincastle County Regiment. Dunmore, Preston announced, had ordered him to assume command of the frontier defenses. In his place, Christian would lead the Fincastle County Regiment. Charles Lewis’s Augusta County Regiment, Fleming’s Botetourt County Regiment, and Christian’s regiment would assemble at a site on the Greenbrier River to be called Camp Union. From there, Andrew Lewis would lead the regiments to the mouth of the Kanawha River, where they would join Dunmore.

The following day, Dunmore learned at Greenway Court how far east the Indians could raid. The attack on Wakatomica, he wrote to the Earl of Dartmouth, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, “has not yet called home those that were on this side of the mountains, for whilst I was at dinner yesterday I was informed that they were murdering a family about fourteen miles from me.”

The appearance today of the high ground from which the Shawnees attacked at the battle of Wakatomica, as seen from the position of the Virginians in the swamp. The sign refers to a nearby archery range. (Author’s photograph)

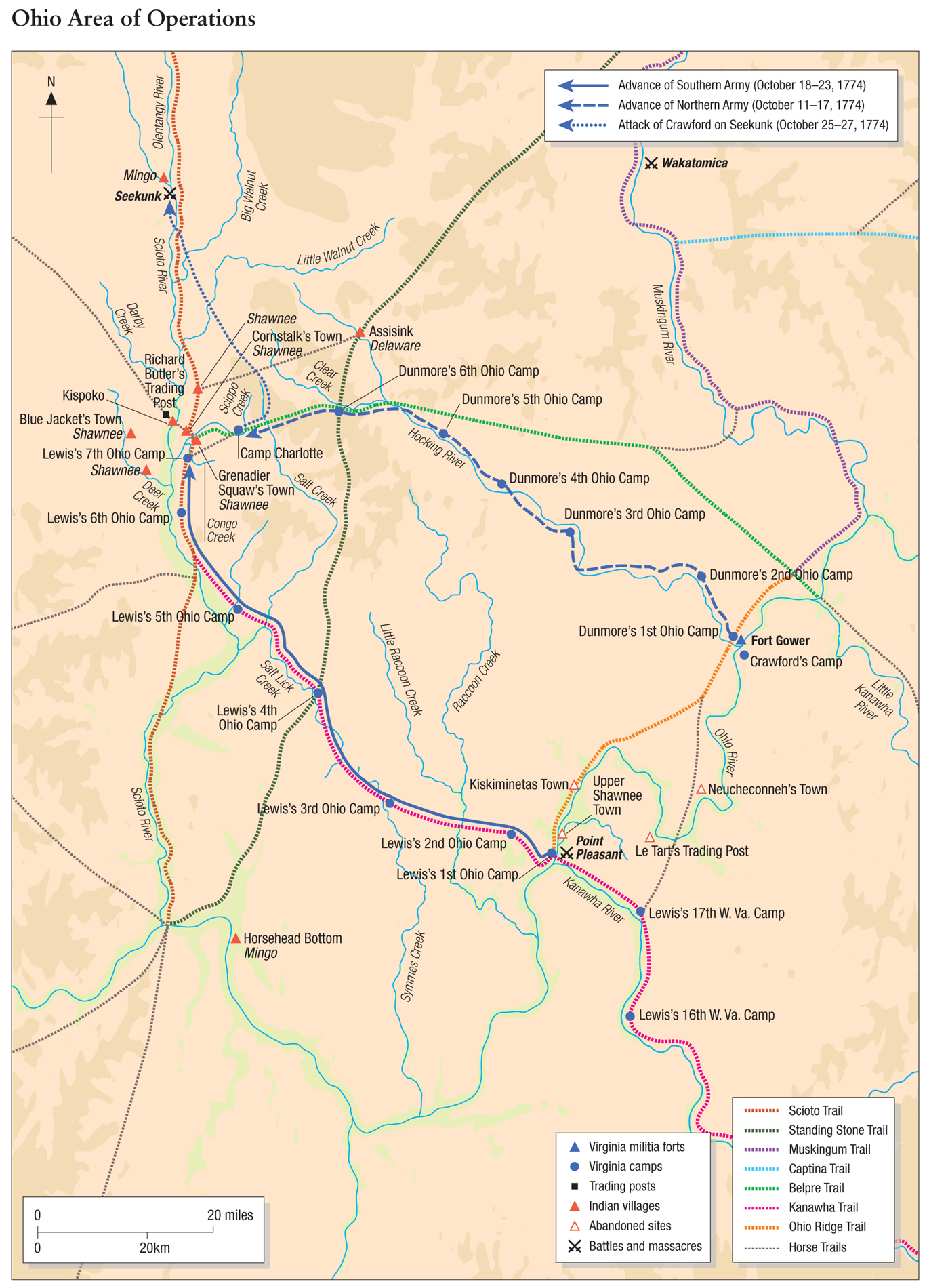

Dunmore’s Northern Army would have about 1,200 men in three components. Stephen was bringing to Greenway Court his 500-man Berkeley County Regiment, and another 100 Frederick County men. They and the men McDonald had led to Wakatomica would form the 500-man Frederick County Regiment, which Crawford, now promoted to major, would lead. Connolly, also promoted to major, would lead approximately another 200 men waiting west of the Appalachians, who would form as West Augusta District Battalion. McDonald would serve on Dunmore’s staff.

On August 27, Stephen’s regiment began advancing up Braddock’s Road toward Pittsburgh. A few days later, Dunmore followed with McDonald and the additional Frederick County men. When they reached Burd’s Road, the Frederick County companies marched to Redstone. Dunmore and McDonald, who continued toward Pittsburgh, then stopped at Crawford’s fort. Crawford, Dunmore said, was to lead the Frederick County Regiment and the army’s packhorses and cattle from Redstone to Wheeling. There, after descending the Ohio from Pittsburgh, the other units of the Northern Army would join him.

In the south, Lewis’s army began to take shape. There would be no trouble recruiting enough Augusta County companies. In less populous Botetourt and Fincastle Counties, however, men were reluctant to leave their families unprotected. After returning from warning Harrod and Floyd in Kentucky, Boone had raised a company, and offered to serve as the army’s guide. But his men wanted to limit their service to guarding against raiders.

Russell and Floyd, however, had raised companies for the Botetourt and Fincastle County Regiments, and volunteers from other counties had come forward to swell the regiments’ ranks. For the Botetourt County Regiment, Field, who had recovered from his escape from Kelly’s Station, would bring two Culpeper County companies, and another from neighboring Dunmore County, which his son-in-law George Slaughter had recruited. Captain Thomas Buford would bring a Bedford County company. For the Fincastle Regiment, Harrod and his men, angry at having to abandon their new cabins at what would become Harrodsburg, Ky., had formed a company of “Kentucky Pioneers.” Captain Evan Shelby would bring a company of Watauga Association men.

By August 29, most of the Southern Army companies had arrived at Camp Union, where they awaited their commander, the Fincastle County Regiment, and Slaughter’s company. On September 1, Andrew Lewis arrived to lead them. That day, 600 miles to the northwest, British Gen. Thomas Gage sent soldiers to seize militia arsenals in Charlestown and Cambridge, Mass.

As Lewis waited for Christian’s Fincastle County Regiment, Indians hovered around Camp Union. On September 2, they wounded a man, and on September 3 another. On September 5, they stole several horses. That day, Washington, Christian’s brother-in-law Patrick Henry, and other delegates from the colonies convened in Philadelphia in the first session of the Continental Congress.

When Christian’s regiment arrived on September 6, Charles Lewis led his men forward on the Kanawha Trail toward the Ohio River, 140 miles ahead. With them went more than 100 cattle, and 500 of the Southern Army’s 800 packhorses, carrying 54,000lb of flour. They were to halt at the mouth of the Elk River, establish a fortified supply camp, and await the rest of the army. On September 10, Field and his Culpeper companies followed.

On September 12, Andrew Lewis and Fleming led forward the Botetourt County Regiment, augmented by Russell’s and Shelby’s Fincastle Regiment companies, with another 18,000lb of flour. At the same time, Dunmore reached Pittsburgh. There Stephen’s regiment and Connolly’s West Augusta District Battalion were ready to embark on a fleet of watercraft that would carry the army and its supplies down the Ohio.

White Eyes and the Delaware chief Captain Pipe were also there. They would go, they told Dunmore, to the Pickaway Plains to try to persuade the Mingos and Shawnees to attend a peace council at the mouth of the Hocking River. The Virginia governor, who had planned to lead the Northern Army to the mouth of the Kanawha, now announced that it would go to the mouth of the Hocking instead. He would arrive for the council, he told the Delaware chiefs, in early October.

Halting at their 2nd through 9th W. Va. Camps, Lewis’s men moved slowly through the difficult country to the east of the New River. On September 20, when Crawford left his fort for Redstone, they reached their 10th W. Va. Camp. The following day, after passing the ruins of Kelly’s Station at what is now Cedar Grove, they halted at their 11th W. Va. camp opposite the mouth of Cabin Creek.

On September 22, Lewis’s men arrived at the mouth of the Elk River, in present Charleston. There, 108 miles from Camp Union, they joined Charles Lewis’s and Field’s men at their 12th W. Va. Camp, the army’s supply base. The combined regiments then began building 27 large canoes to carry supplies down the Kanawha.

On September 27, Christian’s Fincastle County Regiment and Slaughter’s company marched from Camp Union. On the same day, Dunmore left Pittsburgh with Stephen, Connolly, their men, and the army’s flour and other supplies. As the flotilla moved down the Ohio at about 3 miles an hour, the Virginia governor’s guides pointed out the sights on the river’s banks. Nineteen miles downstream on the left was the trading post of Capt. John Gibson and his brother George. Ten miles farther on the right was John Logan’s village, abandoned the year before. Twenty-three miles downstream on the left was Baker’s trading post, and on the right the site of Logan’s hunting camp. Twenty-one miles farther on the right was the site of Crow’s Town, a Mingo village abandoned in 1772.

Michael Cresap lived in this house, which he completed in 1764. It is now a museum in Oldtown, Md. (Courtesy of the Irvin Allen/Michael Cresap Museum)

On September 30, Lewis left a small guard and 50 cattle at his 12th W. Va. Camp, and advanced to his nearby 13th W. Va. Camp, from which the canoes would descend the Kanawha. On the same day, Dunmore’s flotilla, and Crawford’s men, cattle, and packhorses reached Wheeling.

There Crawford received new orders. He and his Frederick County Regiment were to drive the cattle 60 miles down the eastern bank of the Ohio and camp opposite the mouth of the Hocking River. It was a site Crawford knew well. On October 27 and November 7, 1770, he and Washington had camped there while surveying. Now he was to build at the mouth of the Hoching a supply base that would be named Fort Gower.

The men who arrived in Wheeling brought with them alarming rumors about what was happening east of the Appalachians. American militiamen in Massachusetts, it had been reported, were battling Gage’s British soldiers. All shared a hope that Dunmore’s campaign would end at the peace council on the Hocking. A quick peace with the Indians, Crawford’s brother Valentine wrote to Washington from Wheeling on October 1, would allow the men there “to assist you in relieving the poor distressed Bostonians – if the report here is true that General Gage has bombarded the city of Boston.”

When White Eyes and Captain Pipe reached the Pickaway Plains, they found an Indian army of about 700 assembled. To their disappointment, the Mingos and Shawnees rejected their peace council proposal. After the Delawares left, Cornstalk, the Shawnee war leader, then addressed his warriors. The next day, he announced, they would march to attack Lewis’s army.

From a small wigwam, a shaman removed what looked like part of an old blanket that had been wrapped and tied. From the object, one of the five war bundles of the Shawnee subgroups, he removed a series of sacred items. To Cornstalk, he gave an ancient tomahawk, and to four other commanders clusters of hawk feathers to attach to their hair. He then removed a small wooden figure. A carved Shawnee warrior with a bow and arrows, it would preside over the war dance.

To the beat of drums. the Indians sang war songs and danced for hours around a war post, attacking it with tomahawks to display their frenzy. Cornstalk, who had argued for sending emissaries to Dunmore’s peace council, joined the others. But the worried Shawnee commander had little enthusiasm for the battle to come. It would not be enough, he knew, to send Lewis’s men fleeing back to Virginia. Even an overwhelming victory would be disastrous if it left his army too weakened then to defeat Dunmore’s.

After sleeping for a few hours, the excited warriors began forming the single-file column in which they would advance. The shaman tied the bundle to a long pole to form the war beson, the standard under which the Shawnees would fight. Then, before dawn, the Indian army began moving down the Scioto Trail.

In 1774, William Preston built this house at Smithfield Plantation, now a historic site in Blacksburg, Va. (Courtesy of Historic Smithfield Plantation)

Delayed by a day of torrential downpour, Lewis’s men left their 13th W. Va. Camp on October 2. As they and their supply canoes went down the Kanawha, halting at their 14th through 17th W. Va. Camps, Dunmore’s men were moving down the Ohio. Seventeen miles from Wheeling, they reached Captina Creek on the right and, after another 69 miles, the mouth of the Muskingum. Thirteen miles on they reached the mouth of the Little Kanawha on the left. The Hocking was 12 miles ahead. The mouth of the Kanawha, Dunmore’s scouts informed him, was about 50 miles by land beyond the Hocking, and by the twisting Ohio River about 80.

This photograph of the New River Gorge National River, taken about 5 miles west of Lewis’s 4th W. Va, Camp, shows the formidable terrain through which the Southern Army advanced. (National Park Service photograph)

Lewis’s army, Dunmore thought, probably had by now reached the mouth of the Kanawha. The Virginia governor wrote a letter to Lewis, ordering him to proceed immediately to the new rendezvous site. Girty, his young friend Simon Kenton, and another scout then sped down the river by canoe ahead of Dunmore’s fleet. But when they reached the Kanawha, they found that Lewis was not there. Girty then carved a message in the trunk of a hollow tree, saying that Dunmore’s letter to Lewis was concealed inside.

On October 6, as Christian’s advancing regiment halted at Lewis’s 12th W. Va. Camp on the Elk River, Dunmore’s flotilla reached its destination. He found Crawford waiting and his captains, including Clark, who now had his own company. They had begun building Fort Gower. But there were no Indians.

A few hours later, Girty and Kenton arrived. When they reported that Lewis was not at the mouth of the Kanawha, the frustrated Virginia commander asked Girty to go back down the river and up the trail toward Camp Union to find Lewis’s army. As Dunmore prepared another letter to Lewis, Stephen quickly wrote one to the Southern Army commanders as well. After a rest, Girty went downstream again.

That same day, Lewis’s army reached the Ohio. From their 18th W. Va. Camp, the view was stunning. “The dense forest clothed in its autumnal tints,” Fleming wrote in his journal, “and the rivers at low water, with the Ohio resembling a lake and the Great Kanawha an estuary, the whole landscape presenting an enchanting scene. An army of weary men appreciated it and bestowed on it the name of Camp Point Pleasant.”

Lewis’s men soon found Dunmore’s letter. But, to the Southern Army commander’s annoyance, it ordered him to move his army up the Ohio to the Hocking. Lewis immediately dispatched two scouts to tell Dunmore that he had most of his army at the mouth of the Kanawha, but was awaiting the remainder and could not move immediately to the Hocking because his packhorses were exhausted.

On October 7, White Eyes and Captain Pipe arrived at the mouth of the Hocking. There would be no council, they told the Virginia commander. The Mingos and Shawnees were set on war. His army, the angry Dunmore decided, would go forward to the Pickaway Plains.

On October 8, Christian advanced from the 12th W. Va. Camp. Leaving Slaughter’s company to guard the army’s supply base, his other companies marched with 350 cattle toward the mouth of the Kanawha. The canoes that accompanied them carried another 27,000lb of flour downstream.

As the Fincastle men moved down the Kanawha, scouts were scurrying between Dunmore’s and Lewis’s camps in two-day journeys and five-day round trips. On October 8, Lewis’s scouts found Dunmore’s army at the Hocking. On the same day, Girty delivered Dunmore’s and Stephen’s letters to Lewis. Fleming, to whom Lewis showed Stephen’s letter, wrote in his journal that night, “Col. Stephen in his to Col. Lewis says he hears disagreeable news from Boston but cannot assert it.”

Girty then returned to the Hocking with letters from Lewis to Dunmore, and Fleming to Stephen. Dunmore’s army, Lewis urged, should join his at the mouth of the Kanawha. Lewis’s men, Fleming wrote to Stephen, were reluctant to leave a site where they blocked Indian raiders from using the Kanawha Trail and were closer to the Shawnee villages than Dunmore’s army. If Lewis’s men were ordered to move, he added, “I am convinced it would be attended by considerable desertions.”

As the tireless Girty paddled back up the Ohio on October 9, three more scouts sent by Dunmore, including the famous frontiersman William McCulloch, arrived at Point Pleasant with another letter to Lewis. The Northern Army, Dunmore informed Lewis, would march directly toward the Pickaway Plains on October 13. Lewis’s army was to meet his at noon on October 18 at a ridge southeast of the Pickaway Plains.

Consternation spread as Lewis told his officers the news. After experiencing the difficulty of rendezvousing at even a prominent site in the wilderness, Dunmore had now chosen a vague location about 50 miles away, in the heart of where the hostile Indians were concentrated. “What calculations he might have made for delay or other disappointments that might happen to two armies under so long and difficult a march through a trackless wilderness,” Capt. John Stuart of the Botetourt County Regiment would write, “I could never guess.”

Dunmore’s decision would also leave the Southern Army exposed alone to an Indian attack. That prospect, however, did not alarm Lewis and his officers. “Encamped in the forks of the river, in safe possession of a fine encampment,” remembered Major Thomas Ingles, “we thought ourselves a terror to all the Indian tribes on the Ohio.”

At noon on October 9, the Virginians assembled for their usual Sunday religious service. As the afternoon passed, and McCulloch waited to carry Lewis’s response back to Dunmore, he met Stuart. He thought, he told the Southern Army captain, that the Indians would probably attack Lewis’s army soon.

Indian tomahawks were used both in close combat and as throwing weapons at distances up to about 15yd. This tomahawk with a modern handle, unearthed in 2010 at the site of Grenadier Squaw’s Town, was probably used at Point Pleasant. (Jeff Dearth Collection)

As McCulloch and the other scouts began paddling back to the mouth of the Hocking, hundreds of Indians were moving north on the wooded ridge across the Ohio River from Lewis’s camp. About 3 miles upriver from the mouth of the Kanawha, they halted, built 74 rafts, and waited. At 6.25pm, the last sunlight left the sky. At 9.12pm, the last moonlight. Then, concealed by darkness, the first rafts silently began to cross the river.

At 5.30am on October 10, sunrise was still an hour away at the Indians’ camp. Their commander was on familiar ground. When Cornstalk had been a boy, the trading post of James Le Tart, the first British trader in the Ohio Country, had been 11 miles to the east, near the Shawnees in Neucheconneh’s Town and Kiskiminetas Town. In 1738, raiding by the Catawbas had forced Le Tart and the Shawnees to leave. In 1751, the Shawnees had built the village the British called Upper Shawnee Town at the mouth of Oldtown Creek. But in 1756, when Lewis’s Virginians had advanced up the Big Sandy, they had withdrawn again, to villages on the Scioto River.

The Shawnees’ preparations for battle were completed. They had slept for a few hours as they always did while campaigning, leaning against trees or logs or poles extending between forked sticks, their weapons at hand, ready to awaken instantly to respond to an attack. They had eaten as they always ate before a battle. Twelve deer had been killed, and the venison cut into the exact number of pieces the army had warriors. Then the pieces had been roasted and their condition studied by the shaman. Now, after burying their tools, kettles, and superfluous clothing, they were ready to meet the enemy.

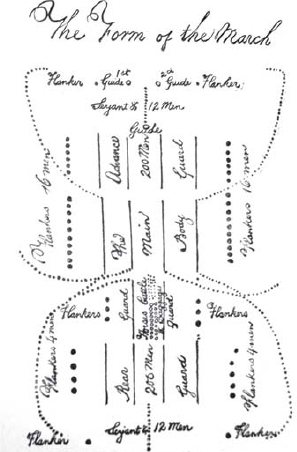

William Fleming’s drawing of the order of march from Lewis’s 13th W. Va. Camp to Point Pleasant, with the Augusta County Regiment as the left column and his Botetourt County Regiment the right. (Author’s collection)

At last, like a great, uncoiling snake, a three-quarter-mile-long column of Indians began moving in single file towards Oldtown Creek and the Virginians’ camp. It was late, thought the Indians’ worried commander. They would advance slowly in the darkness. And when the first sunlight appeared in a half-hour, Virginia scouts might discover them before they reached their battle positions.

Beyond Oldtown Creek, the Indians would advance on a low ridge above the Ohio. About 200–300yd to its left, a parallel ridge overlooked Crooked Creek. Beyond the ridges, the column would descend to the low ground through which Crooked Creek flowed. Its head would reach the creek’s mouth on the Kanawha River, almost half a mile from the Ohio. The column then would become the line from river to river in which the Indians would attack the Virginians.

They would fight, the Shawnee commander knew, on a field defined by three main features. Along two, the Kanawha and Ohio rivers, the Virginians’ tents extended in lines. The third was a massive ridge east of Crooked Creek. Its 250ft-high walls, in places almost vertical, formed a two-mile-long arrowhead aimed directly toward the point where the rivers met, about a half-mile away.

The Ohio River today, as seen from the area where Fleming’s Botetourt County Regiment camped. (Photograph by Ed Lowe)

As the Indians moved silently through the dark woods, the tired pickets at Lewis’s camp were awaiting relief from Capt. Alexander McClanahan’s company, which would provide the new day’s sentinels. The half-mile-long line they guarded, behind which hundreds of cattle and horses were sleeping or grazing, was the long side of a triangle. On the two shorter sides, each more than 500yd long, tents stretched along the rivers. Those on the Kanawha were for 560 men in the 12 companies of Charles Lewis’s Augusta County Regiment. Those on the Ohio were for 570 in Fleming’s Botetourt County Regiment, which included seven Botetourt County companies, Field’s two Culpeper County companies, Buford’s Bedford County company, and Russell’s and Shelby’s detached Fincastle Regiment companies.

Along the Ohio there were a few fires. Tired of their diet of beef and bread, some of the men had risen early to hunt for deer and turkey. Joseph Hughey and James Mooney of Russell’s company, who served as scouts for the army, went first. Sergeant James Robertson of Shelby’s company and Sgt. Valentine Sevier of Russell’s followed. Soon the hunters moved past the pickets on a 250yd-wide area of ground that extended north from the camp toward the ridge on which the Indians were advancing. About 40ft above the Ohio, which was 75yd to its left, it rose about 20ft higher than the low ground to the right, through which Crooked Creek flowed below the high ridge.

As the Indians were advancing, Lewis was at this location, overlooking the Kanawha River (left) and Ohio River (right), in a senior officer’s tent like that used by these re-enactors. (Photograph by Ed Lowe)

This portrait by an unknown artist depicts James Robertson. Five years after the battle, he would build Fort Nashborough, which would become Nashville. (Courtesy of the Tennessee State Museum)

When Hughey and Mooney had gone north about a mile and a half, the first, dim light of morning revealed Indians ahead in large numbers. It also disclosed the two Virginians to the adopted Shawnee Tavenor Ross. After fighting with the Virginians at Wakatomica, he had decided to return to the Indians. A ball from his musket killed Hughey.

As Cornstalk, alarmed that the Indians had been seen, cautiously led his column forward, Mooney raced back to the Virginians’ camp. He reached the northernmost of the Botetourt County officers’ tents, which belonged to Capt. John Stuart. “I discovered a number of men collected around him as I lay in bed,” Stuart remembered. “I jumped up and approached him, to know what was the alarm, when I heard him declare he saw above five acres of land covered with Indians, as thick as one could stand beside another.” Robertson and Sevier then arrived to confirm the presence of Indians.

When Stuart informed the Virginia commander, Lewis lit his pipe. After a few moments’ pause, he ordered his drummers to beat “To Arms,” the signal for the Virginians to assemble for battle. He then decided to send about a quarter of his army up the Ohio in a reconnaissance in strength.

Fleming and Charles Lewis would go north with Botetourt and Augusta County Regiment columns. Each of the regiments’ four most senior captains would go with them, leading 100 men. To avoid delay, Lewis had his company captains choose among their just awakened men 12 or 13 from each unit who were ready to go. Soon the selected men were arriving at their assembly point near the confluence of the rivers. Shelby, Russell, Buford, and Capt. Philip Love, who would accompany Fleming in the column on the left, placed the arriving Botetourt Regiment men in their column’s two files. Charles Lewis’s captains, John Dickinson, Benjamin Harrison, Samuel Wilson, and John Skidmore, whose column would advance on the right, did the same for the Augusta Regiment men.

The 150yd-long columns then went forward toward the place where Mooney had seen the Indians. Mooney led Fleming’s column on a route about 100yd to the right of the Ohio River. Another scout led Charles Lewis’s column on a parallel course about 150yd to the right of Fleming’s.

By 6.33am, when the sun at last rose over the high ridge beyond Crooked Creek, the head of the Indian column was nearing the creek. Scouts then reported that the Virginia columns were approaching from the Indian column’s right. The news confirmed Cornstalk’s fear. Discovered before they had formed their line from the Kanawha to the Ohio, the Indians would have to begin the battle here. After summoning forward more men from the column, he positioned his warriors ahead of the Virginians in cover to ambush them.

Fleming’s column advanced about 550yd beyond the northernmost pickets guarding the Botetourt County Regiment tents. Charles Lewis’s trailed about 100yd behind. Then, recalled an officer who had remained in the camp, “Three guns went off, which was immediately followed by several hundreds.”

This scene of autumn woods near Wellston, Ohio, shows the conditions in which the Virginians and Indians fought. During the battle, the Indians concealed beneath piles of leaves bodies that would later be carried from the field. “I saw a young man,” Capt. John Stuart recalled, “draw out three that were covered with leaves beside a large log in the midst of the battle.” (Author’s photograph)

The first musket balls killed Lewis’s scout. Hundreds more then hit the advancing Augusta County column. As the Virginians paused in shock, the Indians reloaded, and fired a second volley. Before they fired a third, Lewis’s men had scattered behind large trees and logs. When the Indians ahead of Fleming’s column heard the shots, they immediately opened fire. Musket balls killed Mooney. Fleming’s men then scattered too.

When attacked from the front, the Virginians in each file were to wheel forward, away from the other file, to form a line at the front of the column. As the officers tried to move the men into lines, and to join the left flank of Lewis’s line to the right of Fleming’s, they attracted Indian fire wherever they could be seen.

Lewis soon fell. He was shot, Christian was told, “in clear ground as he had not taken a tree. He turned, handed his gun to a man and walked to camp, telling the men as he passed along, ‘I am wounded, but you go on and be brave.’”

Fleming fell too. Two balls hit his left arm. Then another struck his chest. But the wounded Botetourt County colonel urged his men not to retreat. “With great coolness and deliberation,” an eyewitness remembered, “he stepped slowly back and told them not to mind him but to go up and fight.”

As the Augusta and Botetourt column captains tried to form their lines, they faced a difficult challenge. The men they tried to move into positions, drawn from different companies, refused to obey their commands. “There was no one officer who had his own men,” Floyd wrote after the battle, “and it was impossible for the officers to collect their own men so that when they saw any doing no good, and ordered them to advance, they refused and said they would be commanded by their own officers.”

Charles Lewis carried these surgical tools at the battle; they are displayed at the Mansion House Museum in Point Pleasant. (Photograph by Ed Lowe)

Under the heavy fire, moreover, the number of captains began to dwindle. In the Augusta column, Wilson soon fell dead, and Dickinson and Skidmore wounded. In the Botetourt column, Buford was mortally wounded.

On the left, Evan Shelby, Russell, and Love maintained a degree of order. There the Ohio River provided a point upon which the Virginians could anchor their left flank. Falling back toward the end of their column, the Botetourt Regiment men were able to begin forming a rough line from their left toward the Augusta County men to their right.

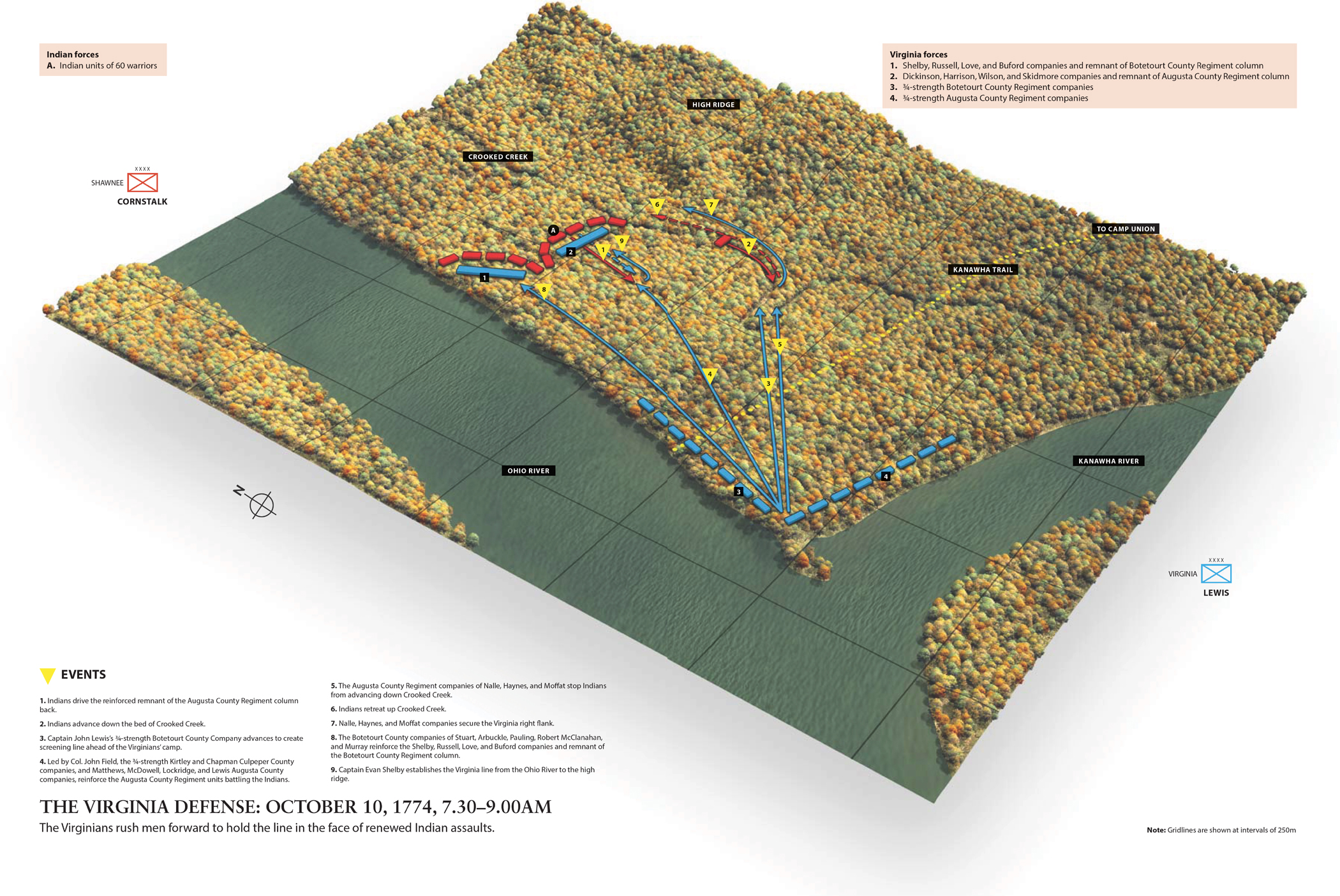

THE INDIAN ATTACK, OCTOBER 10, 1774, 6.45AM (PP. 60–61)

A column of 700 Indians advancing toward the Kanawha River discovered that two parallel columns of 150 Virginians were approaching, marching in the opposite direction. The Indians then halted their advance and prepared to ambush their enemies. The scene shows Shawnee warriors commencing their attack on the Virginia column on the Indian left, which contained Augusta County militiamen led by Col. Charles Lewis. A Shawnee shaman (1) has earrings hanging from ear lobes that were partially severed and distended, a common practice among Ohio Indians of the time, and wears the roach headdress usually worn by Shawnee warriors in ceremonies. He is holding the tribe’s battle standard (2), the beson, a pole carrying one of the Shawnee subgroups’ sacred war bundles. The Shawnee war chief Cornstalk (3), who has given the command to fire, is waving a tomahawk (4) taken from the war bundle, probably one of the first axes with a metal blade obtained by the Shawnees from the French in the 17th century. This Shawnee warrior (5) has begun the battle by firing his musket. Ahead, one of two scouts (6) leading Lewis’s Virginians has been hit by a musket ball. Behind the scouts, partially concealed by the trees and undergrowth, Lewis’s 150 Virginians (7) are advancing in a two-file column. This warrior (8), who lacks a musket, is firing an arrow from his bow. Concealed by the foliage, warriors (9) extending back through the woods along the length of the column now fire into the Virginians. Beyond the scene, 150yd to the right, Indians hearing the fire have begun to attack Col. William Fleming’s parallel Virginia column of Botetourt County militiamen.

On the right, where only Harrison remained among the captains, there was chaos. Charles Lewis’s column had ceased to be an organized militia force. What followed, however, showed the capacity of even a leaderless collection of experienced frontiersmen in a battle in the woods. The Virginians, Stuart judged, “had no knowledge of the use of discipline or military order.” But they also “were well skilled in their own manner of warfare.” Some of the men Charles Lewis had led raced back to the camp seeking safety. But most found places behind trees and logs, searched for targets, and fell back only when pressed too hard.

The appearance today of the area where the head of Charles Lewis’s column was attacked, near Pioneer Cemetery. (Author’s photograph)

The ambush had killed many Virginians. But its disruption of Cornstalk’s battle plan soon became apparent. Some of the warriors at the head of his column moved forward in the bed of Crooked Creek toward its mouth. But most who had attacked the Virginians pressed their assault. As the Indians remaining in the column reached the field, they searched for positions in which they could join in the attack.

When men fleeing from the ambush reached his camp, the Virginia commander learned that the engagement was not just a skirmish. In addition to McClanahan’s 65-man camp guard, he had about 750 men available to deploy, in companies reduced to three-quarter strength by the diversion of men to the columns. “Col. Lewis,” Fleming wrote his wife three days later, “who, as we did not expect a general engagement, was in camp, behaved with the greatest conduct and prudence, and by timely and opportunely supporting the lines ... prevented the enemy’s attempts to break into the camp.”

Lewis first ordered the lieutenants of the captains who had marched with Fleming and Charles Lewis to take their companies forward to support their beleaguered commanders. Lieutenant Isaac Shelby, the lieutenants of Russell’s, Love’s, and Buford’s companies, and about 140 men went up the route the Botetourt captains had followed. The reinforcements soon reached Evan Shelby, who had assumed command of the Botetourt men. Their arrival ended the threat of a further Indian advance. Shelby then began to extend the Virginians’ position to the right, incorporating into his ranks men who had been in Charles Lewis’s column.

Four Augusta County lieutenants led their men up the path that Dickinson, Harrison, Wilson, and Skidmore had followed. They entered an area where the Indian warriors were forcing back the outnumbered Virginians. But their 95 additional rifles slowed the Indians’ advance.

The Virginia commander next ordered Capt. John Lewis, whose cousin of the same name led an Augusta County company, to deploy his 55-man Botetourt company in a screening line between the camp and the area where fighting raged. Behind them, he ordered the approximately 470 men of the remaining companies to begin felling trees. They were to be used to build breastworks along a line between the furthermost tents on the Kanawha and Ohio.

Charles Lewis left a pregnant widow, who named her son after his father. In 1800, the younger Charles Lewis settled near the site of the battle. The photograph shows his house about 2 miles north of Point Pleasant, which survives as Old Town Farm. (Photograph by Ed Lowe)

As the Indians continued to advance on the Virginians’ right, the wounded Fleming returned to the camp. He met Charles Lewis, who already had been carried there. “I have sent one of the enemy to eternity before me,” Lewis told Fleming before expiring.

When the Virginia commander learned that Fleming and Charles Lewis had fallen, he dispatched Field to take command of the units battling the Indians. With him, Lewis sent additional reinforcements. Up the route of Charles Lewis’s column, Field led forward about 200 men in his two Culpeper County companies, and the Augusta County companies of Capts. George Matthews, Samuel McDowell, Andrew Lockridge, and John Lewis.

Although Shelby’s reinforced Botetourt County Regiment companies had halted the Indians’ advance, the Virginians on the right now had been pushed back more than 400yd from the point where they had been attacked. Field’s force stopped any further Indian advance. But then Field fell. At the time, Christian was told, he was “behind a great tree, looking for an Indian who was talking to amuse him whilst some others were above him on his right hand among some logs, who shot him dead.”

Worried that the Indians might advance to the mouth of Crooked Creek, and attack the camp from the east, Lewis sent about 120 men of the last remaining Augusta County companies, led by Capts. William Nalle, Joseph Haynes, and George Moffat, to stop them. After fighting in and around the bed of Crooked Creek, the Virginians reached the base of the high ridge. The Indians, recalled Stephen Mitchell, a settler who had joined Lewis’s army after escaping Indian captors, then “were driven, with the loss of half their force, back upon the main body.” An anonymous officer, probably Moffat, led the last company to arrive at the ridge. “I was ordered out with fifty men,” he wrote, “to a certain place to prevent the Indians getting round our camp. I, with my men, run about half a mile and came to some of our men by a hill. The Indians had retreated.”

The Indians forced the Augusta County companies back to this area. (Author’s photograph)

Lewis had retained as a last reserve the Botetourt County companies of Stuart and Capts. Matthew Arbuckle, Henry Pauling, Robert McClanahan, and John Murray. When he learned that Field had fallen, Lewis decided to commit them. With orders that Evan Shelby was to assume command of the Virginians fighting the Indians at the front, the Botetourt captains and their almost 200 men went forward on the route that Fleming had followed.

With the new reinforcements, Evan Shelby moved to the southeast. There he forced the Indians back and began incorporating the Augusta County men into a coherent line. By 9 o’clock, he had accomplished his assignment. The Virginians on the right, recalled Isaac Shelby, finally were “in a line with the troops left in action on the banks of the Ohio by Col. Fleming.” “Our people at last formed a line,” Christian wrote to Preston after the battle. “So did the enemy.”

The engagement had not proceeded as the Indian commanders had planned. It now threatened to become what Cornstalk had wanted to avoid, a battle of attrition. When conditions changed, and the Indians no longer had any advantage on a battlefield, Indian commanders usually withdrew their men to fight another day. But the desperate Shawnees and Mingos were uncertain that there would be another day.

The base of the high ridge in the area where the Virginians established the right end of their line. (Photograph by Ed Lowe)

The battlefield, which stretched about 600yd from the Ohio River to the high ridge, would not allow the Indians to use their usual tactics. They could not attack the Virginians’ left flank, which was guarded by the Ohio. Nor their right, which rested on the high ridge. Even where the ridge’s cliffs weren’t vertical, the incline was so steep that a flanking movement was impractical.

Their enemies, moreover, now were beginning to recover ground. When attacked, Indian warriors usually fell back to minimize casualties, intending then to surround attackers who had advanced too far. But this battle could no longer be won by tactics designed to minimize casualties. To prevail, the Indians would have to break through the Virginia line. The Indian warriors, their commanders ordered, must not retreat. They must attack.

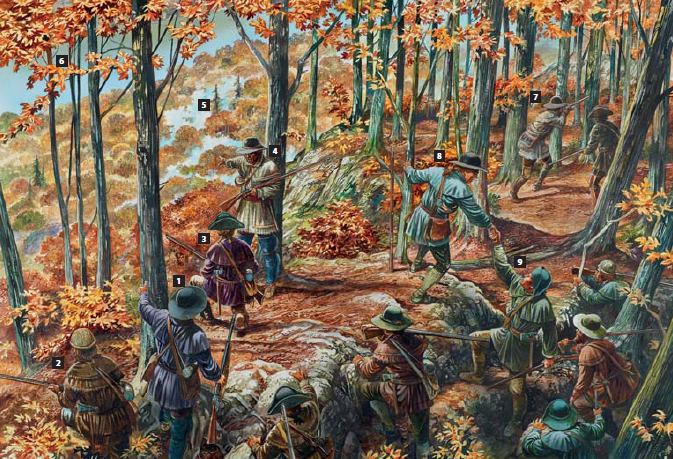

The stiff resistance of the reinforced Virginians had diminished the distance between the combatants. Now the tenacity of the Indians reduced it further. The Virginians could hear the Indians’ shouts and taunts. Stuart heard a Shawnee chief yelling commands to his warriors. “One of my company,” he remembered, “who had once been a prisoner, told me what he was saying, ‘Be Strong. Be strong.’” Some of the Indians’ insults were in English. From behind trees and logs came cries of “sons of bitches” and “white dogs.”

Used to fighting almost invisible warriors, the Virginians now battled an enemy they had never fought before. “The Indians,” remembered Major William Ingles, “disputed the ground ... inch by inch.” They showed “the greatest obstinacy, often running up to the very muzzles of our guns.” “Never,” wrote Fleming to a friend after the battle, “did Indians stick closer to it, nor behave bolder.” “I cannot,” Christian wrote to Preston, “describe the bravery of the enemy in battle. It exceeded every man’s expectations.”

Much of the combat, a survivor remembered, was at very close distance. The Virginians and Indians, said one, were “never above twenty yards apart, often within six, and sometimes close together, tomahawking one another.” “Hide where I would,” Mitchell recalled, “the muzzle of some rifle was gaping in my face and the wild, distorted countenance of a savage was rushing towards me with uplifted tomahawk.”

The Virginia casualties grew steadily. Soon, in Robert McClanahan’s company, the captain and lieutenant died and the ensign was wounded. In Murray’s, the captain was killed, and in Arbuckle’s, Capt. James Ward. Many of the militiamen suffered multiple wounds. Private John McKinney of Moffat’s company returned to the Virginia camp with a musket ball wound in his left thigh, another in his left wrist, and a grievous tomahawk wound in his upper back.

Decades later, Mitchell remembered with a shudder what the combat had been like. In a series of dark dramas, individual militiamen and warriors had fought for the prize of life. “The contest,” he wrote, “resembled more a circus of gladiators than a battle.”

Sometimes speed and dexterity determined the outcome of the combatants’ grim duels. Men who had fired their weapons raced their opponents to reload. Both knew that, at such close distance, the winner’s ball would not miss.

Others were tests of judgment. Men who realized that they could not win their reloading races had to decide instantly whether to dash for cover, or towards their opponents. Those who sprinted forward, leaping over logs and fallen branches, had to weigh the chances that, if they threw their tomahawks or knives, they would hit their targets or arrive unarmed.

Sometimes men won their duels by deceit. Private Richard Burk of Russell’s company, pretending that he’d been hit by a musket ball, thrashed on the ground in death throes. Too eager to claim Burk’s scalp, the Indian who had fired the shot ran forward. He learned too late that Burk was alive with a loaded rifle. After taking the Indian’s scalp, the satisfied Virginian took a break from the combat to eat. “I believe,” he said to a companion, “I’ve earned my dinner.”

Others, like Mitchell, survived by strength and ruthless ferocity. As he reloaded his rifle, an Indian racing forward threw a tomahawk. The Virginian dodged the weapon, which buried its blade in a tree. In vicious hand-to-hand combat, the two then wrestled for survival. Mitchell, after crippling his opponent. finally retrieved the tomahawk and killed him. The Virginian, however, had had enough. “I immediately rose,” Mitchell wrote 53 years later, “and gaining a secure position behind a tree, remained there till the close of the fight, and made a thousand resolutions, if I survived this engagement, never to be caught in such a scrape again.”

Here Indian Hectors fell, and there Virginian Goliaths. But the Indians had no advantage in such contests. Any ground they gained against Shelby’s men was soon lost. At last, the Indians ceased their reckless attacks and began to fall back.

While camped at Point Pleasant, Evan Shelby shaved with this razor. After his death in 1777, it passed to Isaac Shelby, who carried it with him during the Revolutionary War. (Kentucky Historical Society, Mrs Susanna Preston Shelby Collection, 1952.44)

The line Shelby had created was rough. “There were never,” wrote Capt. John Floyd, “more than three or four hundred of our men in action at once, but the trees and logs the whole way from the camp to where the line of battle was formed served as shelters for those who could not be prevailed on to advance to where the fire was.” And, he added without naming names, “Many of the officers fought with a great deal of courage and behaved like heroes, while others lurked behind and could by no means be induced to advance to the front.”

But the number of Virginians on the front was enough. They now, moreover, could fight the battle they had expected. On a field only 600yd wide, hundreds of eyes searched the woods for the locations of Indian muskets. A fired musket’s flame and smoke attracted the attention of a dozen Virginia marksmen, each capable of targeting any Indian head, hand or foot that became visible. Protected by their covering fire, other Virginians ran or crawled forward toward the area where the musket had flashed.

Yard by yard, the Indians fell back before the Virginians’ deadly rifle balls. “We pursued them,” wrote Moffat, “from tree to tree.” “The close underwood, and many steep banks and logs,” Isaac Shelby remembered, “greatly favored their retreat.”

Hour after hour it continued, with the opposing battle lines slowly but steadily moving north. And every hour the lines grew longer, as the Virginians on the left pushed forward faster than those on the right. By noon, Fleming’s aide John Todd remembered, the Indians opposing the Botetourt Regiment companies had been compelled “to retreat about a mile.”

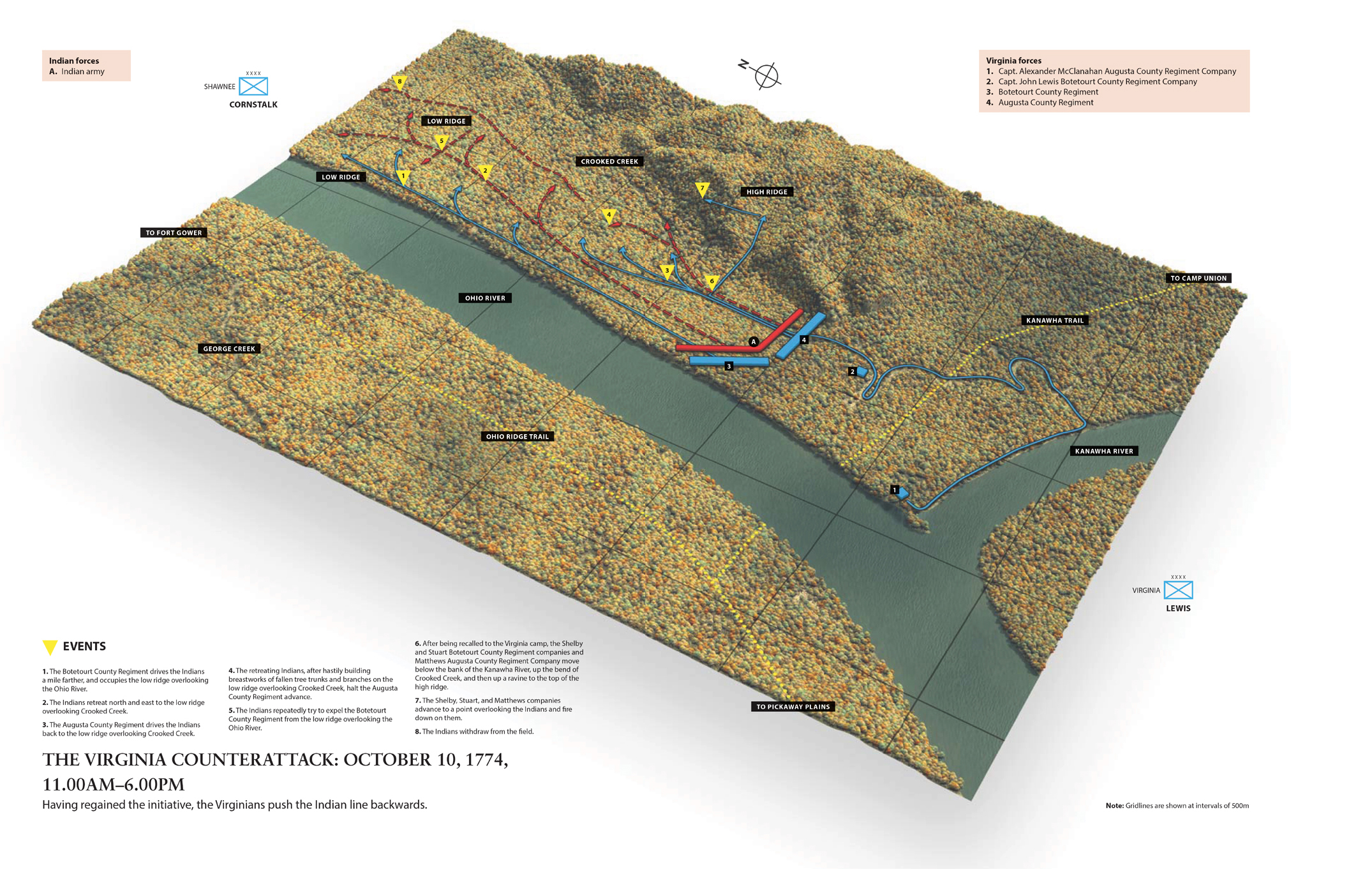

But the Indians’ “long retreat,” remembered Isaac Shelby, “gave them a most advantageous spot of ground.” At the north end of the field two long, low ridges pointed at the Virginians like prongs of a fork. The Indians falling back from the Botetourt County Regiment at last occupied the ridge upon which they had advanced that morning. The Botetourt County men then fought their way up, and occupied ground far along the ridge’s length. “This advantageous post being gained about one o’clock,” Todd remembered, “all the efforts of the enemy to regain it proved useless.”

The Virginians on the right, however, had more difficulty. When the Augusta County Regiment companies pushed the Indians back to the other low ridge, they found refuge behind a natural breastwork of fallen tree trunks and branches. “They placed themselves behind logs,” Moffat remembered, “fired on us, killed three men near me, and wounded ten or twelve more.” The Augusta County men nonetheless “pushed up farther.”

But after fighting for six hours, and suffering heavy casualties, Lewis’s militiamen were exhausted. “Our men,” Christian wrote to Preston, “could have forced them away precipitously, but not without great loss, and so concluded to maintain their ground all along it, which they did until sundown.” “It appeared to the officers,” remembered Isaac Shelby, “so difficult to dislodge them that it was thought advisable to stand as the line was then formed, which was about a mile and a quarter in length.” “The whole line from the Ohio to us,” recalled Moffat, halted “at the same time. This happened about one o’clock.”

THE CLOSE COMBAT, OCTOBER 10, 1774, 10.00AM (PP. 70–71)

After hours of fighting, the Virginians have finally formed a line and begun to push the Indians back. The Indians, desperate to drive the Virginians from the field, have redoubled their efforts to break through the Virginia line. Much of the fighting now is at a close range. A Virginia militiaman (1) who has reloaded his rifle faster than a Shawnee warrior ahead of him is now aiming his weapon to kill the Indian. Realizing that he has lost the race to reload, the warrior (2) is dashing to find cover behind a tree. Another warrior (3), concealed from the Virginian by a tree, is creeping forward to attack him as another Virginian (4) arrives at the scene. A Virginian wounded by a thrown tomahawk (5) is lying on the ground. A friend (6) who has run to save him is battling the Shawnee who had thrown the tomahawk (7). Another Virginian (8) is reloading his rifle as a warrior (9) runs forward to attack him.

The appearance today of the low ridge held by the Indians against the Augusta County Regiment, as seen from the base of the ridge occupied by the Botetourt County Regiment. The trees in the background are on the high ridge. (Author’s photograph)

The battle, the shocked Indian commanders knew, had been lost. Even the almost superhuman efforts of their warriors had not been enough. But the consequences of failing to drive Lewis’s army back to Virginia were too dire for them to accept. Again and again, warriors tried to expel the Botetourt County Regiment from the low ridge near the Ohio. “Tho they would summon all the force they could raise,” Todd recalled, “and make many pushes to break the line, the advantage of the place and the steadiness of the men defied their most furious essays.” Then, Floyd wrote, “The Indians retired to a thick place where there had been a town and damned the white men for sons of bitches.”

As the afternoon began to wane, the Indian attacks grew less frequent. But Lewis remained wary. Up the Kanawha, he knew, Christian’s companies were advancing toward the battlefield. At 3.00pm, he dispatched messengers to the Fincastle County Regiment commander, ordering him to hasten to the field as quickly as possible.

Then it began to rain. As the leaves covering the ground grew ever wetter, the last hopes of the Indians slipped away. Many of their best commanders and warriors were dead or wounded. Even the shaman who had carried the beson had fallen, and the war bundle’s sacred objects had been lost. All thoughts of victory abandoned, the Indian commanders decided to leave the field.

They assigned units to hold the Indian line while most of the army retired. Ordered to create the appearance that the Indians were still fighting, the remaining warriors fired, screamed, and taunted. As they performed their martial charade, other warriors fashioned litters from fallen tree branches to carry the dead and wounded. Still others raced back to the Indian camp to retrieve their buried goods and the rafts on which they had crossed the Ohio.

The stratagem deceived the Virginians. Worried that the Indians might renew their attack that night or the next day, Lewis decided to try to force them to leave the field. The high ridge beyond Crooked Creek towered above the low ridge where the Augusta Regiment companies had halted. From there, the Virginians could fire down on the Indians, and threaten to attack them from behind.

Lewis recalled from the line 150 men in Shelby’s company, now led by Lt. Isaac Shelby; Stuart’s company; and the company of Capt. George Mathews. At a point about 300yd behind the far right of the Augusta County Regiment line, a small run had eroded the high ridge’s incline. There Shelby’s, Stuart’s, and Matthews’s companies could climb to the high ridge’s top.

THE HIGH RIDGE, OCTOBER 10, 1774, 5.00PM (PP. 76–77)

The advance of the Augusta County Regiment has halted at a low ridge beyond Crooked Creek, which the Indians are defending behind a crude breastwork of fallen tree trunks and branches. Three companies, led by Capts. John Stuart and George Matthews, and Lt. Isaac Shelby, have been sent to climb a much higher ridge from which they can fire down on the Indians. The scene shows the Virginians reaching the top of the high ridge. A Virginian (1) from Stuart’s company is using a tree trunk to pull himself up the steep incline while another (2) has paused to catch his breath. Stuart (3) is kneeling on a rocky outcrop near the summit discussing with Capt. George Matthews (4) the location of the Indians below. On October 4, 1777, Matthews would suffer nine bayonet wounds while leading a regiment at the battle of Germantown. He later would be elected governor of Georgia. In the distance, smoke rising through the trees below (5) marks the course of fighting in the battle as the Ohio River (6) flows beyond. This militiaman in Matthews’ company (7), who thinks that he has seen an Indian, has raised his rifle to fire. Lieutenant Isaac Shelby (8), now commanding his father Capt. Evan Shelby’s company, has reached the same outcrop. Shelby would win fame as a commander at the battle of King’s Mountain on October 7, 1780, and would later be the first governor of Kentucky. He is helping his friend Sgt. James Robertson (9), who is leading the men of Shelby’s company up the ridge. Robertson and Lt. John Sevier of Capt. William Russell’s company would be remembered as the fathers of Tennessee.

This modern path follows the route of Shelby’s, Stuart’s, and Matthews’ companies to the top of the high ridge. (Author’s photograph)

To conceal their movement from Indians on the high ridge, Stuart later wrote, the Virginians “proceeded under cover of the bank of the Great Kanawha for three-quarters of a mile to the mouth of Crooked Creek, and thence along the bed of its tortuous course to their destination.” As the afternoon approached its end, the three captains led their men to the top of the high ridge, and on to a position about 300yd from the Indians. The distance was too great for riflemen to target individual warriors, who were also concealed by the canopy of leaves above them. But the Virginians, Stuart recalled, “poured a destructive fire on the Indian rear, and they believing that this was the long-expected reinforcement, under Colonel Christian, gave way, falling back toward the place from which they came that morning.”

As night approached, the Virginians watched cautiously as the flashes from Indian muskets diminished and the shouts of the Indian warriors dwindled to silence. “An hour by sun,” Todd remembered, “we were in full possession of the field of battle.” Lewis then ordered his men to retire to the camp. “Victory having now declared in our favor,” Todd recalled, “We had orders to return in slow pace to our camp, carefully searching for the dead and wounded to bring them in, as also the scalps of the enemy.”

The Virginians collected 32 scalps, which they attached to a post at the end of the point where the Kanawha and Ohio met. About 40 Indians probably died in the battle, including the Shawnee commanders Puckeshinwa and Silver Heels. About another 70 were wounded, including the Delaware war leader Buckongahelas.

But it was their own dead and wounded that mattered to the Virginians. By 6.30pm, when the last light left the sky, they were back at their heavily guarded camp. There the talk was of casualties. All were shocked by the names of the officers who had fallen. Charles Lewis and Field both were dead, and Fleming was expected to follow them. Among the captains, Buford, Robert McClanahan, Murray, Ward, and Wilson all had been killed, and Dickinson and Skidmore wounded. And when the counting was done, word spread that a fifth of the army had been lost. In all, about 80 Virginians had been killed, and another 140 wounded.

After traveling 12 miles up the Kanawha, Lewis’s messengers reached Christian at 7.00pm. He and his Fincastle County Regiment companies were encamped with their herd of cattle and fleet of canoes near what is now Leon, W. Va. There they had planned to rest before marching to join Lewis’s army the next day.

After leaving a small guard with the cattle and canoes, the Fincastle County Regiment commander led about 200 men forward on a five-hour night march. “We pushed on and got in about midnight,” Floyd wrote to Preston, “where we were warmly received. And I imagine that if our number had been double what we were, we should not have been complained of for that. I understand we were much prayed for that day in time of the engagement... Some gentlemen tell me that it appeared doubtful for some time.”

Twenty-two years after the battle, Pvt. Walter Newman returned to the site of the Virginians’ camp. There he built this 1796 tavern overlooking the Ohio River, now the Mansion House Museum at Tu-Endie-Wei/Point Pleasant Battlefield State Park. (Photograph by Ed Lowe)

On October 11, Lewis’s men awoke early, expecting the Indians to attack again. After hours passed without shots being fired, Lewis sent Christian’s Fincastle County companies up the Ohio to search for enemy warriors. After following the tracks of the retreating Indians to the river, they found the Indians’ rafts on the other side. The Virginians then spent the day burying the bodies of the Southern Army’s dead.

The men at Dunmore’s camp also rose early on October 11. After telling Lewis that he would advance on October 13, the impatient Virginia governor had again changed his mind. The day before, as the battle had raged, his army had crossed the Ohio. Watercraft had carried 1,400 men and 250,000lb of flour as 200 packhorses and 100 cattle had swum across the stream.

Established in 1764, Assisink was at the site of the Standing Stone, a 200ft-high outcrop of rock. The photograph shows an exposed portion, in what is now Rising Park in Lancaster, Ohio. (Author’s photograph)

After resting at their 1st Ohio Camp beside the fort, the Northern Army now would march to the Pickaway Plains. Leaving 100 men to garrison the fort, about 1,300 went forward. White Eyes and Captain Pipe, worried about conflict between Dunmore’s men and Indians who were not hostile, agreed to accompany them. The route to the Pickaway Plains, they knew, would pass near Assisink, a Delaware village.

Girty, Kenton, McCulloch, and a corps of the most capable scouts in the wilderness led the way. The Indians watching the army’s progress soon learned not to be careless. Girty, who detected one hiding 200yd away, felled him with a rifle shot. After crossing the Ohio Ridge Trail, which led to opposite the mouth of the Kanawha, the Virginians moved cautiously up the Hocking to the mouth of Federal Creek. There, after 11 miles, they halted at their 2nd Ohio Camp, near present Beebe.