The Symbolic Language

Each card in the tarot deck is unique, but there are common elements that reappear in different cards. To be consistent in our interpretation we need a symbolic language that gives meaning to these elements. For example, what is the significance of the color red? How do we interpret the number three (as a card number or as the number of objects)? What do the right and left sides of the card represent? What is the meaning of animal figures?

New decks from the twentieth century are often based on a symbolic language that can be learned from books or other written sources. For example, when Waite or Crowley designed their tarot decks, they also published books explaining the significance of various symbols in the cards. But the Tarot de Marseille evolved for many centuries in the hands of many people who left no written records about its meaning. Therefore, we don’t have direct access to its original symbolic language. We have to figure it out for ourselves.

To construct a consistent symbolic language for the Tarot de Marseille we can rely on several sources. First, many symbols in the tarot also appear in other works of art from the medieval and Renaissance periods. It is likely that they kept much of their original significance when transferred to the tarot cards. Second, there are various spiritual and cultural traditions that give meanings to symbolic elements that appear in the cards (for example, colors, numbers, or animal figures). Third, we can profit from the experience and insights gained through more than two centuries of tarot interpretation by many authors. And last but not least, we can each rely on our own intuition and feelings, taking the cards themselves as our guide.

In the following sections I present the main elements of a symbolic language that can be applied to the Tarot de Marseille: directions, colors and shades, numbers, figures and body parts. Since the Tarot de Marseille is the original basis for almost all other tarot decks in use today, many elements in this symbolic language can fit other decks as well.

Before we continue, a word about cultural and ethnic biases. The Tarot de Marseille deck is a product of the Renaissance and early modern Europe. As such, its illustrations reflect the biases and limitations typical of this particular culture. For example, religious symbols are Catholic, couple relationships are heterosexual, “flesh color” is a reddish tone of beige, warrior figures are male, and so on. To understand the card symbols as originally intended, we have to consider them from a point of view that takes these biases for granted. However, when using the cards, we should look for the broader meaning behind them and adapt it to the particular circumstances of the querent. For example, we may interpret the Catholic symbols as representing the religious or spiritual aspirations of the querent, whatever their religious affiliation might be. We shall elaborate more on this point later on, when we discuss male and female figures in the cards.

Directions

left and right

The horizontal axis that goes from left to right is marked in the card illustrations by the ground surface, and so it brings to mind the earthly reality of everyday life. Movement along this axis can represent the sequence of events in our lives, from childhood to old age. This raises the question of time and its direction along the horizontal axis: is the past on the left and the future on the right or vice versa?

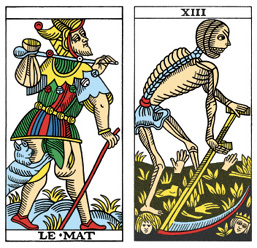

To answer this question we can turn to the cards themselves. Among the major suit cards there are two that are exceptional: the Fool and the card numbered 13. All the other major cards have both a name and a number written on them, but the Fool has no number and card 13 has no name. Note that although the illustrations are quite different, the two figures have a similar posture.

The Fool, Card 13

As we shall see in the detailed card descriptions of Chapter 6, these two cards can represent two aspects of the concept of time: the moment of the present and the timeline of events. The Fool appears to be living only in the here and now. Thus, he can symbolize the present moment: always between the past and the future, always on the move. In contrast, card 13 expresses the timeline of history; that is, the sequence of events in which everything is born, lives, and dies in order to clear the ground for new things. In both cards the figures walk to the right. If they represent our movement in time, from the past to the future, it means that the past is on the left and the future is on the right. We can notice that the French script on the cards also goes from left to right, and consider that for people used to reading in European languages, movement in this direction appears natural.

This idea of movement from left to right can be applied both to the image of a single card and to the ordering of several cards in a spread. In a single card a figure walking, looking, or pointing to the right is oriented toward the future, while a figure looking to the left of the card is referring to the past. We can also think of the right direction as expansion and moving out, while the left represents retraction and drawing in. In a spread we read the cards as a story that goes from left to right. The cards on the left speak of what came before, and the cards on the right speak of what comes after.

In speaking of the arrangement of objects and figures relative to the card frame, this interpretation of left and right is clear. But when we consider a human figure in the card illustration, another question arises: which side of the figure is the right one and which is the left? For example, if the figure is shown facing us, should we consider it like a real person (so that her right hand is on our left side) or rather like a reflection of ourselves in the mirror (so that his right hand is on our right side)?

This question is significant if we want to interpret the sides of the body according to the traditional symbolism of right and left. The right side of the body is taken to represent hardness, action, and initiative. The left side represents softness, reception, and containment. So, which side of the figure represents action and which one represents reception?

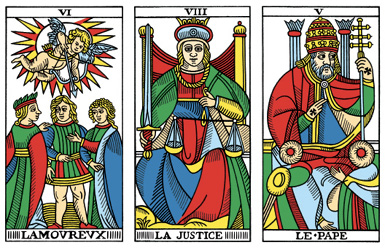

We can get hints about this question from three major cards that show traditional symbols connected with body sides. As we shall see in Chapter 6, the lower part of the Lover card probably refers to a mythological story about Hercules standing between a younger woman and an older woman. According to the legend, the older woman stood to his right. But in the card illustration the older woman is on the left side. This is like a person standing in front of us, not like a mirror.

A similar conclusion can be drawn from the Justice and the Pope cards. In sculptures and paintings of the Justice figure, such as can be seen in courts today, it is holding a sword in its right hand and a balance in its left hand. In the illustration of the Justice card, the sword appears on the left side and the balance on the right side. The Pope figure makes the Latin gesture of benediction with two straight fingers, which is done in the Catholic tradition using the right hand, yet the hand making the gesture is on the left side of the card. Thus, in all three cards we see the left and the right sides of the body as if it was a real person in front of us. We can assume that the same holds true for other cards as well.

The Lover, Justice, The Pope

up and down

The traditional shape of the tarot cards is a narrow rectangle. In the Conver and the CBD decks, the proportion between the sides is almost exactly two to one, like two squares standing on top of each other. This shape suggests the idea of dividing the card area into a top and a bottom part, giving each one of them a specific meaning. In the actual card illustrations we can see such a division, not exactly into two equal parts but still present. But as we go over the suit cards, we can see this division taking two distinct forms.

Most of the cards at the beginning of the major suit show a large figure filling the card. Around the middle of its height there usually appears a clear horizontal line or stripe dividing it into a top and bottom part. As we shall see later when we discuss the significance of body parts, the top part can represent the higher functions of reason and emotion, while the bottom part can represent the basic or lower functions of body and desire. Thus, the way in which the two parts of the figure relate to each other can represent the relation between the higher and lower functions in the querent’s life.

Most of the cards in the last part of the suit show a different division of the vertical axis. At the bottom of the card there is some happening taking place on the ground, while the top shows some object in the air or in the sky. The relationship between these parts can be interpreted as an encounter or a link between the earthly reality at the bottom and a celestial or higher reality at the top. We can understand this as some connection with superior levels of being; for example, getting messages or protection from above. It can also be a representation of heaven and what it stands for: superior good, happiness, charity, spirituality, enlightenment.

In some cards of the major suit there is also a third level: an abyss that appears as an opening in the ground or as a black surface at the bottom of the card. The abyss may represent deep forces acting in the unconscious mind, hidden dark passions, or something secret buried under the ground. When the abyss is black we can interpret it as pain, fears, or traumatic memories of past experiences in the querent’s life or family history. It can also be interpreted as difficult or unresolved issues from past incarnations.

The vertical axis is therefore manifest in the arrangement of three layers, one on top of the other: the abyss, or hell; the earth; and the sky, or heaven. We can take this to be its basic significance, even though in most of the cards only one or two of the three layers appear. Thus, in contrast with the “external” horizontal axis, the vertical axis can represent inner experience — how the querent feels emotionally and spiritually. For example, a card illustration that suggests a movement going down can indicate difficult and heavy feelings, while going up represents lightness, optimism, and happiness. A possible exception is the vertical axis in the number cards, as we shall discuss in Chapter 10.

The combination of the two axes is also meaningful. Sometimes we can notice a diagonal flow line going through a single card or perhaps passing between several cards in a spread. Such a line can be perceived in the arrangement of eye-catching image details, in the orientation of colored shapes or lined areas, in oblong objects directed along it, and so on. If such a diagonal line goes from the bottom left to the top right, it is ascending: as time advances in the right direction, the line is rising. Thus, it may indicate a positive direction of improvement and advancement. In contrast, a diagonal line leading from the top left to the bottom right marks a descent with time, thereby indicating recession and decline.

Colors

The colors of the cards have a great impact on the emotional effect that they produce in us. Bright colors give the card a light and happy character, while dark colors make it heavy and grim. Warm colors create an atmosphere of action and movement or, when restrained, of human contact and feeling. Cold colors suggest calmness, withdrawal, and emotional distance. Colors also have a great impact on the visual connections between cards. Areas with the same color in neighboring cards may continue each other and thus bring together the separate cards into one image. This effect is especially strong in the Tarot de Marseille, where the cards are painted with a restricted scale of uniform, basic colors that easily join across different cards.

To compensate for the limited color scale, which was made necessary by the stencil coloring technique, traditional tarot card makers introduced a distinction between clear areas, which are plain colored, and shaded areas covered with parallel black lines in addition to their coloring. There are several lining patterns for the shaded areas, and each can be given its own meaning.

Sometimes the lines are short and cover only one side of a colored shape, which is thus divided into a shaded part and a clear part. The shaded side may represent a dark or hidden aspect of an issue, while the clear side may represent a lit and visible aspect. Other areas, such as ground formations, bodies of water, and also some objects, are filled with long parallel lines. When the lines are wavy they may express flow, movement, and instability. When they are straight they may indicate something solid and stable. Straight lines can also suggest an artificial object or tilled land, that is, something on which work has been done.

In various versions of the Tarot de Marseille there are usually between seven and ten colors (including the white background and the black printed lines). In the Conver and the CBD tarot decks there are eight basic colors: white, black, red, blue, yellow, green, light blue, and flesh color. The black and white naturally appear in all the cards, but some of the painted colors are used only in part of the deck. With few exceptions, the major suit and the court cards show all the eight colors. The number cards are painted only in yellow, red, and light blue. The aces in the coins and cups suits have yellow, red, light blue, and green, to which the aces of wands and swords add the flesh color.

In the CBD deck there are additional color effects that I have introduced for various reasons. In some of the original Conver cards two colors are painted one on top of the other. For example, yellow is painted over black at the bottom part of card 13, and light blue over yellow (which creates a greenish tone) in the Ace of Coins and the Ace of Cups. To reproduce a similar effect with the modern printing techniques, I used a computer-colored texture.

I also added a lighter shade of flesh color. In the original Conver deck many of the faces and some hands were left white — that is, without coloring. However, the contrast between flesh color and the white paper is much stronger in modern printing techniques. Leaving these faces white would have made them weird and lifeless. On the other hand, I didn’t want to lose Conver’s distinction between the white faces on some of the cards and the flesh-colored faces on other cards. My solution was to do the originally white faces in a lighter shade of flesh color, which may express a more detached and less emotional attitude.

It is interesting to note that in the complete deck, the painted colors (that is, except black or white) are present in different amounts. The total area of shapes colored in yellow is by far the greatest. This is followed by red, light blue, flesh color, green, and blue. We can see that the warm and active colors, yellow and red, are the most common, while the cold and calm colors, green and blue, are the rarest. If this choice was motivated by artistic and not by practical considerations (for example, an excessively high price of the blue pigment at that time), we can understand that Conver wanted to give his cards a warm and dynamic character, rather than cool and absorbing.

In the symbolic language framework, each color in the cards can be given a specific meaning. The following list of meanings for the eight colors of the Conver and CBD decks is derived from various sources, including traditional and modern art, mystical theories, and tarot writings. I have also added a correspondence of the eight colors to a model of eight elements. This extends the classic model of four elements in Greek and medieval cosmology. The eight elements are light, darkness, earth, fire, water, air, vegetable, and animal.

white: The source and the unification of all colors, suggesting light from a superior source and pure spirituality. As the background color of the cards, it represents an open space of possibilities, the undefined and the limitless. In the card illustrations it appears as the color of the sky, symbolizing high and benevolent levels of existence beyond the material world. Details in white appearing in an image represent purity and innocence, an idealistic action, or remoteness from practical reality. It can also express feelings of superiority, emotional frigidity, or a lack of life energy.

black: Appears on all the cards as the illustration lines, which define the concrete and limited aspect of the image details. In some cards there are also surfaces painted in full black. They can express shaded aspects of reality or dark layers of the soul, such as the depths of the subconscious, past traumas, or feelings of pain and distress. In the symbolic language of alchemy black is the color of the basic matter, which is refined in order to become the philosopher’s stone. In this respect, black surfaces can represent the starting point for a process of development leading from darkness to the light.

yellow: A bright color that gives the cards a warm, illuminated, and optimistic feeling. In the tarot tradition it usually symbolizes intelligence applied to practical needs. Yellow coloring of objects such as crowns, cups, and coins may suggest that they are made of gold. As such, it can symbolize material success and plenty or an active and beneficial force, as in the alchemical symbolism of metals. In many cards the ground appears in yellow, as if it is illuminated by sunlight. This may represent a blessing coming from above or favorable conditions for growth and advancement. Yellow signifies the element of earth.

red: A strong and dynamic color, full of passion and energy, red expresses activity and movement, the power of instincts and desires, outward-oriented action, or anger and aggression. Red is connected with the planet Mars in astrology, with iron in alchemy, and with war gods in various cultures. It can represent combativeness, assertiveness, or courage in front of challenges. Red signifies the element of fire.

blue: A deep and calm color, blue appears in the cards as the opposite of red. It symbolizes attraction and inbound movement, the ability to contain and to accept, submission to circumstances, self-reflection, intuitive understanding, or empathy and compassion. The color blue in a card can also symbolize deep feelings and sentiments that are difficult to express in clear words. Blue signifies the element of water.

light blue: The color of the sky, a lighter degree of blue indicates a combination of matter and spirituality. It can also express clarity and transparency, truth and honesty, but also coldness and detachment. One can see in it a symbol of a wider, more comprehensive perspective or an action that rises above petty and selfish considerations. Light blue symbolizes the element of air.

green: The color of plants, the vegetable element representing growth and change, green hints at nature and natural things. Green may represent an impulse of growth and development, a potential for fertility, a new beginning, or a simple, unsophisticated vision of reality.

flesh color: A reddish tone of beige expresses what is alive and human. It may represent the body, sensuality, animal drives, or the fulfillment of physical needs. Also, as the animal element, it can represent motion and sources of movement. As the color of the naked body, it may also represent openness, exposure, or vulnerability. A flesh-colored object may represent something that is part of the querent’s identity or personality.

Numbers

A number can appear in a tarot card in several ways. It can be the serial number of a card in the major suit (for example, card 4, the Emperor) or in a minor suit (for example, the 6 of Wands). It can be the number of a group of objects or the details in a card illustration, such as three windows in the Tower card, two cups in the Temperance card, or seven little stars in the Star card. A card may also show a geometric shape expressing a number, such as a triangle representing the number three or a square representing the number four.

There are various methods of attaching meanings to numbers, a practice known as numerology. Most of the Western systems of numerology derive from the ideas of the ancient Greek mathematician Pythagoras. In the Pythagorean system the even numbers are considered feminine, stable, and containing, while the odd numbers (except for number one) are masculine, forward-moving, and active. The number one is considered the root of all numbers, so it represents a unity beyond the opposition of male and female.

Mathematical relations between numbers are also related to their meaning in numerology. For example, four is two times two, which stresses the stable character of the even numbers. Thus, four can symbolize the stability of matter. The number six is the multiplication product of the first feminine number (two) and the first masculine number (three). In Pythagoras’s system this is a symbol of marriage, so six may represent harmony and integration of opposites.

There are other numerological systems, and some of them have been applied to the tarot. For example, several tarot decks of the English school are based on the Golden Dawn system, which gave the numbers additional meanings connected with Cabbalistic symbolism and the Hebrew alphabet. The major suit of the tarot can also serve as a numerological source because for each number we can attach the meaning of the corresponding major card. For example, if we ask ourselves about the meaning of the number three, we may think about the Empress, which is number three in the major suit.

The numbers between one and ten are considered most significant, and higher numbers are often regarded as a repetition of the basic ten. Several tarot authors accept this vision and regard, for example, the Devil card (number 15) as a more complex aspect of the Pope card (number 5). Yet sometimes numbers larger than ten can have their own distinct identity. For example, twelve is the number of zodiac signs — that is, a full cycle that goes through all possibilities. The number thirteen adds another unit, so it represents a disruption of the cycle and an opening to a new and uncertain domain.

Combining elements from various systems of numerology, here is a list of meanings for the first ten numbers that can be used in tarot readings. Some numbers also have typical geometric forms associated with them.

One: The basic unit, root of all numbers. As the beginning of the number series, one opens every process, thereby containing its whole course as a potential. It can also represent wholeness and the union of opposites. The geometric shape associated with it is a point, which represents concentration and focus, especially when it appears at the center of a circle. In the major suit the number one is the Magician, which opens the suit and also expresses the individuality of the single person. In a minor suit it is the ace card, which represents a beginning, a drive, or an action in the suit’s domain.

Two: Opposition, duality, polarity. It can represent a partnership or a romantic relationship, a conflict between two elements, or a quandary between two options. The tension between the poles has a potential of generating movement, but due to the static nature of the even number it does not happen yet. In the Chinese tradition the number two represents the complementary elements yin and yang, the feminine/passive and the masculine/active. In the major suit it is the Popess with a screen dividing the world into two parts, revealed and hidden. Two points, two objects, or two parallel lines in a card express a pair of opposites. These may be active and passive when side by side or heavenly and earthly when one is above the other.

Three: The third unit breaks the stalemate of the number two and adds movement and creation. The number three represents dynamism, flow, fertility, and the forces of nature. In many cultures it is a number associated with sorcery, such as a conjuration formula repeated three times. Its corresponding shape is the equilateral triangle, but it can also be represented by three parallel horizontal lines, symbolizing the abyss, the earth, and the sky. Three objects or three points may represent a movement toward realization. In the major suit it is the Empress, often associated with fertility and growth. In the Christian tradition it also hints at the Holy Trinity, thus representing a divine presence in the material world.

Four: Solid, stable, secure, and conservative. It represents material, earthly, and tangible things, practical considerations, and the structure of established systems or institutions. It also symbolizes matter (the four elements of earth, water, air, and fire) and physical space (the four cardinal directions). Its typical shape is a square, with a stable base securely resting on the ground. In the major suit the number four is the Emperor, expressing domination in the physical world. Four objects in a card can represent a practical realization or the act of reaching a tangible goal. One can also see them as symbolizing the four minor suits, representing balanced achievements in different life domains.

Five: The odd unit breaks the stable structure of the number four and adds to it something from another plane. This can represent a disruption of a stable and secure structure, but also the opening up of a new dimension. The corresponding shape is a five-pointed star with two possible positions. When the tip points upward, it represents the figure of a human being (head, two arms, two legs) and serves as a magical symbol with a benign influence. When the tip points downward, it can represent negative forces and black magic. Five is also represented by a square-based pyramid, with four corners on the ground and one apex in a higher plane. In the major suit it is the Pope, acting within an earthly establishment but pointing to a higher spiritual level. The number five also symbolizes the structure of the tarot deck itself, with one major and four minor suits.

Six: The number six expresses harmony, as a union of opposite factors (2 x 3) or as a combination of two complementary processes (3 + 3). The Pythagoreans called it a perfect number because it is equal to the sum of all its divisors (1 + 2 + 3). In the Cabbala it is identified with Tiferet, the center of the Sefirot Tree, representing the ten aspects of the Divine. The shape representing it is the Star of David, which is a fusion of two complementary triangles. In the major suit it is the Lover, expressing a romantic relationship and also a harmony between human choices on earth and the decree of heaven.

Seven: As 6 + 1, the number seven creates a new movement out of the harmony of six, yet as 4 + 3 it expresses a combination of material stability and the energy of motion. Thus, it has a mysterious and sometimes confusing character, with an unsolved inner opposition between abundance and success, on the one hand, and disruptive instability on the other hand. Such an opposition is expressed by the Chariot card, with a square structure enclosing the triangular shape of the rider’s head and arms. The inner tension of the number seven can also have a productive aspect, opening up a whole spectrum of possibilities, such as the seven colors of the rainbow, the seven days of the week, the seven metals in alchemy, or the seven planets in ancient astrology.

Eight: The different combinations of two and four (2 x 2 x 2, 2 + 2 + 2 + 2, 4 x 2, 4 + 4) bring together the dividing aspect of the number two, with the ability to distinguish between opposites, and the solid framework of the number four. Thus, eight can represent rational constructions, well-defined systems of rules and laws, discerning and going into detail, or long and patient work needed to build a stable structure. In the major suit it is the Justice card, whose upper part suggests a logical and stern framework with straight lines and right angles.

Nine: A combination of dynamic processes (3 x 3 and also 3 + 3 + 3) that express complexity, a variety of possibilities, and movement that does not proceed in one clear direction. The number nine is also almost ten, so it expresses a strive to perfection but also an inability to reach this goal completely. In the major suit it is the Hermit card, which expresses a spiritual quest and self-examination. It can also hint at a reality beyond the senses and is related to intuition and mysticism.

Ten: As the basis for the number system, ten stands for a totality or culmination. In the Cabbala it symbolizes the Tree of Sefirot, which are the ten aspects of the Divine. Ten represents the final outcome of the evolution, which starts with the number one, and the opening of a new cycle of numbers. As 5 + 5 it can represent a combination of both good and bad, like a cyclical process that involves both ascent and decline. In the major suit it is the Wheel of Fortune, which expresses the completion of a cycle and a return to the starting point.

Figures

Human figures appear in the major suit cards and in the court cards of the minor suits. It is interesting to note the difference in gender representation between these two parts of the deck. In the court cards of each suit there are three men and one woman. This can reflect the fact that the minor suits have developed separately, and their court cards are modeled after the traditional power structures of society.

In contrast, the major suit shows no clear preference of men over women. There is even some balance between masculine and feminine roles, such as the Emperor and the Empress or the Popess and the Pope. The equal status of the two genders can look surprising if we remember that the major suit cards were designed in a very conservative era. Still, the opposition of male and female is a basic feature of most traditional symbolic systems. We can assume that although the creators of the major suit cards didn’t show a basic preference to either side, they did have such an idea and sought to express what each of the two genders symbolized.

In many of the traditional systems the masculine side, or the yang element as it is called in Chinese culture, is regarded as active, firm, moving forward, and outgoing. The feminine side, or the yin element, is regarded as passive, gentle, containing, and inward oriented. This opposition, which may be inspired by the shape and function of the sex organs, is reflected in traditional symbolic systems by other pairs of opposites: right and left, the sky and the earth, the sun and the moon, the rational and the emotional, the lighted and the shaded. With some exceptions (for example, a male moon god and a female sun goddess in Japan), the first element in each of the pairs is generally regarded as masculine, while the second element is regarded as feminine.

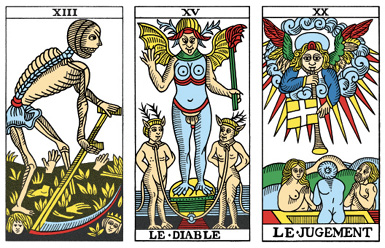

We can also note that three cards of the major suit show a pair of human (or semihuman) figures that look like male and female. These are the severed heads in card 13, the little imps in the Devil card, and the two parental figures in the Judgment card. In all three the figure on the right is masculine, while the figure on the left is feminine. This may suggest that tarot symbolism also accepts the identification of the right side as male and of the left side as female.

Card 13, The Devil, Judgment

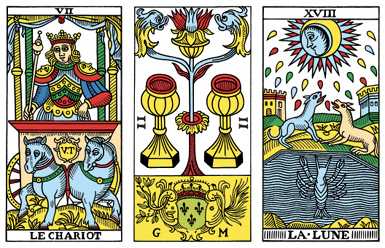

Still, there may be some deeper structure of male-female interplay in the cards. If we look at animal figures we can see some pairs that vaguely look male and female. But if we identify them as such, their arrangement is the opposite compared to the human figures. Jodorowsky notes that in the Chariot card, the horse on the right looks feminine while the horse on the left looks masculine. The same may also be said about the two fantasy fish heads in the 2 of Cups, or even the two dogs in the Moon card when we look at their muzzles.

The Chariot, 2 of Cups, The Moon

Relying on traditional associations of male and female may seem outdated in our day. But an important point to remember is that a figure of a woman in the cards does not necessarily represent a woman in reality. Today we are aware that in each of us, regardless of our biological gender, there is both a masculine and a feminine side. Therefore, a woman figure in the card can represent a feminine aspect, or a behavior traditionally considered as feminine, in a man. And, of course, a man in the card can represent a woman in reality who acts in a way traditionally associated with masculinity. We can thus rely on the traditional symbolism of male and female without assuming anything about the actual status that men and women should have in society.

Similar considerations apply to the age of figures in the cards. A young figure can symbolize the beginning of a process or the first steps taken in a new domain of action. It can also represent stamina, naive self-confidence, or rashness. An older figure can symbolize maturity, experience, and moderation. These qualities may describe the personality, the behavior, or the position of the querent, regardless of their biological age.

Children and animals, too, can symbolize aspects of personality and behavior. The figure of a child in a card may express childlike qualities such as spontaneity, imagination, playfulness, and short-sightedness. Animals can represent a primordial and undeveloped state or animal instincts and impulses. Specific animal figures can represent personality traits and behaviors traditionally associated with this kind of animal. For example, a lion can symbolize bravery, power, and danger. An eagle can symbolize sharp perception or the ability to soar high above common ground. A dog can symbolize loyalty. A more formal way to interpret the lion or the eagle, which appear in the World and in other cards, is to identify them with the minor suit domains described in Chapter 7. In such a scheme, the lion corresponds to the suit of wands and represents desire and creativity, while the eagle corresponds to the swords and represents the intellect.

Body Parts

Body parts of the tarot figures can be interpreted in several ways. One way is to interpret the body parts metaphorically according to their function and use. For example, a hand symbolizes what the querent is doing. An eye symbolizes what they can or want to see. The shoulders can represent the burden they are carrying. A belly is what they contain and keep inside. A woman figure with a round belly can express pregnancy with something, not necessarily a real child. The legs represent the stability of the querent’s position or their ability to move. Whatever is under them can be the basis on which they stand.

I have also learned another way to interpret the body parts from Jodorowsky. It is based on the symbolic language of the minor suits. As we shall see in Chapter 7, the four suits represent four domains of human activity: body, desire, emotion, and intellect. These four domains correspond, from bottom to top, to four parts in the human body: legs, pelvis, chest, and head. When we see a figure in the cards, we can check the position and appearance of each part and the relation and coordination between them. This can teach us about the corresponding domains in the person’s life.

the legs represent the suit of coins and the material and physical domain, or “what we stand on.” Strong and stable legs represent a secure position, a solid material base, and good health. A walking figure means that the querent is advancing in some direction. Standing with the feet pointing in one direction expresses a desire or an intention to move there, without an actual movement yet. Standing with the feet spread in both directions can express confusion, contradicting plans, and hesitation and quandary between different courses of action.

the pelvis, which includes the sexual organs, represents the suit of wands and the domain of desire and creativity. A prominent pelvis indicates strong passions. A hidden or covered pelvis can express repression, blocked sexual desires, or a lack of sexual self-awareness. The pelvis can also symbolize creative expression, as it represents giving birth to something coming from within ourselves: children, ideas, or projects.

the chest, seat of the heart, represents the suit of cups and the domain of emotion. A wide and open chest represents emotional receptivity and sensitivity, or the capacity to express and to react to others’ feelings. A contracted or blocked chest — for example, in tight clothes or behind armor — can symbolize closeness, emotional protectiveness, and a difficulty to express intimacy. Touching the area of the heart indicates a relationship based on warmth and trust. If the chest leans toward another figure, it may indicate affection and positive feelings or a desire to have a romantic relationship with that person.

the head represents the suit of swords and the domain of the intellect. A head turned to one side means that this is the direction of the querent’s thoughts. A covered head or gathered hair symbolizes controlled and orderly thoughts, while loose and flowing hair represents fresh and open thinking. A line separating the head from the rest of the body can express an inner detachment, with the querent’s thoughts disconnected from other parts of their personality.