The Major Suit

When people consider the magic and the symbolic power of the tarot, which is responsible for its huge impact on many generations, they usually think about the twenty-two cards of the major suit. Without the major suit we would have a deck similar to the normal playing cards: a convenient means for games of chance and popular fortunetelling, but not something that could motivate centuries of preservation, development, interpretation, and creativity, as the tarot cards have done.

The Suit at the Center

The relationship between the major suit and the four minor suits can be seen symbolically in the World card, which is the last one of the major suit. In its corners there are four living creatures taken from biblical tradition: bull, lion, human, and eagle. These can symbolize the four minor suits and the four domains of life, which we shall review in chapter 7: body, desire, emotion, and intellect. The four figures define a solid rectangular frame, which also brings to mind the regular structure of the four suits. The dynamic element appears in the middle, in the form of a naked figure dancing within an oblong wreath. In the tarot deck it can represent the major suit. In the human sphere it can symbolize consciousness, which unites the different functions into a single entity.

Many tarot readers see the minor suits as representing only external and practical dimensions of life events. In the cards of the major suit they see a fuller and deeper representation of human life: both the external events and the inner life of self-consciousness, psychological processes, and spiritual intuitions. This may be the reason why popular fortunetellers, who are not interested in going into deep levels of analysis, usually use only the normal playing cards, which are equivalent to the four minor suits. In contrast, tarot readers attach much more importance to the twenty-two major cards.

The major suit differs from the minor suits not only in the richness and complexity of its card illustrations but also in its less orderly and more chaotic structure. The four minor suits follow a fully predictable pattern. After the 4 of Cups comes the 5 of Cups, and just as there is a Knight of Swords, there is a Knight of Coins. In contrast, the cards in the major suit display a complex and unpredictable sequence. To demonstrate this point, let us consider a situation where people see all the cards from the beginning of the major suit up to a certain card. From this information, they would still have no way of guessing the title or the subject of the card that follows.

This characteristic sets the major suit apart from other systems of symbolic illustrations that were common during the Renaissance. An interesting example is a collection of card-like prints from the later fifteenth century. They are known as Tarocchi del Mantegna (the Tarot of Mantegna), although they are not really tarot cards and the attribution to the famous painter Mantegna is unfounded.

The Mantegna prints are divided into five suits of ten images each, with symbolic subjects taken from the conceptual world of the Renaissance. The five suits represent themes like professions and social positions, liberal arts and sciences, the nine muses, moral virtues, and celestial objects. Some of the subjects are similar to tarot cards. For example, there is an Emperor, a Pope, and images representing Force, Justice, the Sun, and the Moon.

Still, the Mantegna prints are very different from the tarot. First of all, it is not even clear that they were meant to be used as a deck of cards. In the surviving originals the images are printed on thin paper and bound together as a book, perhaps for educational purposes. This gives them a well-defined and single standard ordering. In contrast, tarot cards can be arranged and read in any order. This means that there is an element of chaos inherent to the tarot cards by the fact that they exist as a set of separate images that can be freely arranged.

The more orderly character of the Mantegna prints is further expressed in the regular structure of the five suits, none of which are exceptional in size or structure. All the illustrations are consecutively numbered, and each one of them has a title written at the bottom. Moreover, when sets of symbols are used they are presented in their completeness. For example, all the nine muses appear consecutively, without any one missing, and the same is true of the seven traditional planets, the four cardinal virtues, and so on.

In contrast, the tarot major suit presents a complex interplay between order and chaos. Time and again orderly patterns appear, and time and again they are broken. Each rule seems to have its exceptions, and the exceptions again differ from each other.

Most cards in the major suit carry titles and ordinal numbers, but the two cards that we have already discussed as representing time in the previous chapter, the Fool and card 13, are exceptional. Card 13 has no name, and the Fool has no number. In addition, there is an empty band on top of the Fool card where the number should be, but there is no similar band for the missing name in card 13. This means that each one of them is exceptional in its own way.

Trying to go over the major suit cards by sequential numbers as a way of establishing a standard ordering proves to be quite confusing. Already the Fool is problematic because without a number, we can’t know for sure where it should be. Putting it aside and looking at the sequence of the other cards, we quickly find that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to find any clear logic.

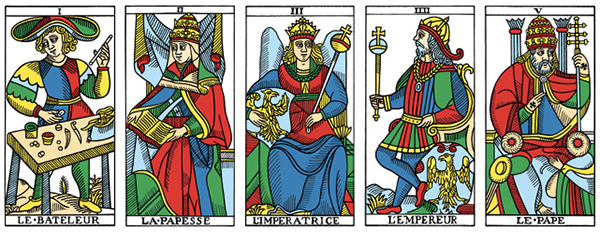

Just after the beginning of the suit, there are four cards with figures of authority and government in an order that is surprising by itself: the Popess, the Empress, the Emperor, and the Pope. But both before and after them there is something completely different. The Magician that precedes these respectable figures looks like a dubious street person. And after the Pope with its Christian symbols there is something even stranger: the Lover with a pagan Cupid and three human figures touching each other. It’s not clear exactly what we see here and why it appears right after the four representative figures of the established social order.

The Magician, The Popess, The Empress,

The Emperor, The Pope, The Lover

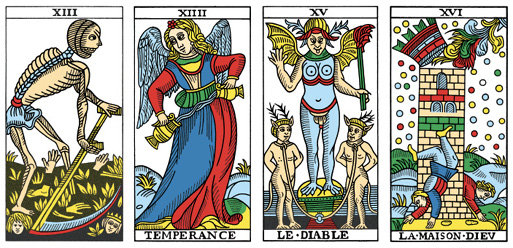

More patterns appear further along the line, only to break down once again. Three major cards present, at equal intervals, three of the four cardinal virtues in Christian tradition: Justice (eight), Force (eleven), and Temperance (fourteen). But the fourth virtue, Prudence, is missing. The Temperance card presents another exception. It is the only card in the major suit whose French name is written without the definite article, as “Temperance” and not “La Temperance.”

Justice, Force, Temperance

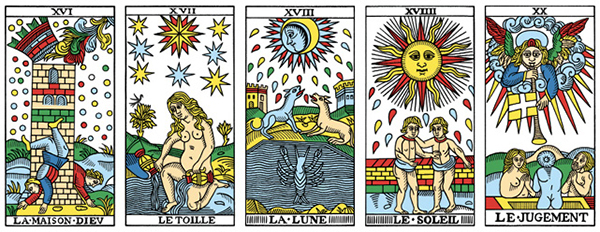

Further along in the suit there are three cards with astronomical and alchemy-inspired symbols: the Star, the Moon, and the Sun. Yet before them we find the Tower, with a different symbolic language whose origin is unclear. And after these cards comes the Judgment card, which is again linked to Christian symbolism.

The Tower, The Star, The Moon, The Sun, Judgment

Many tarot books over the last two centuries have tried to find a uniform and logical order in the major suit. Some of their authors have based their attempts on the ordering of the cards, for example by dividing the suit without the Fool into three sets of seven cards, or into seven sets of three cards. More complex patterns were also tried. None of them have proved convincing enough to gain general acceptance.

Other authors have tried to find order in the cards by imposing a system of symbols taken from other sources. For example, many have tried to establish a correspondence between the major suit cards and the astrological symbols of planets and zodiac signs, but notably each have done so in a different way. The Golden Dawn leaders tried to integrate the cards into their huge table of worldwide correspondences. But again, a disagreement soon appeared as to how exactly to do it. Apparently, in each of these schemes some cards naturally find their place. But then there are others that do not fit so easily, and finally there are some that really have to be forced into their corresponding slots.

Some of the correspondences created over the years are interesting and may enrich our understanding of the cards. One such example is the correspondence between the cards and Hebrew letters, outlined later in this chapter. But perhaps we should not attach too much importance to any orderly table or any scheme for the definite arrangement of the cards. The breaking of patterns in the major suit could itself carry an important message for us.

Scientists today speak of the phenomenon of life as emerging “on the edge of chaos,” a sort of intermediate region between chaos and order. The perfect order is expressed by a solid crystal, where everything is well-ordered and fixed. It has no potential for movement, and thus no place for life. The total chaos is expressed by smoke, which has no stable shape. Here, too, there can be no life because every structure would quickly dissipate. Biological and social life processes take place somewhere in between the crystal and the smoke. They are characterized by a certain degree of order and stability, but also by creative unpredictability and an occasional collapse of ordered structures.

The cards in the major suit, which express and reflect the infinite complexity of life, also can be thought of as a system on the edge of chaos. They show some degree of order and structure, but also chaotic irregularities and pattern-breaking. Therefore, it might be pointless to look for an ultimate structure behind them. The only pattern in the cards is the cards themselves.

Titles and Numbers

In the Tarot de Marseille the number of each card appears in roman numerals. The notation is a long one in which, for example, nine is written as VIIII and not as IX. Perhaps this was done to prevent confusion when the cards were held upside down. In new decks of the English school the numbers are sometimes written in roman numerals in short notation (i.e., nine is IX) and sometimes in modern numerals.

The numbers and titles of the major suit cards are basically the same in both schools, but there are two differences. The Golden Dawn leaders wanted to have more order in the cards. For this reason they made the two exceptional cards in the Tarot de Marseille conform with the others. They gave the title Death to card 13, and this title appears in many decks of the English school. They also put the number zero on the Fool card, thus placing it at the beginning of the suit. There are also some decks in which the Fool is given the number twenty-two and placed at the end of the suit.

Another difference between the two schools is in the numbering of the Justice and Force cards. In the Tarot de Marseille and other traditional decks, Justice is number eight and Force is number eleven. But in new decks from the English school, Force is eight and Justice is eleven. The reason for this lies in the complex system of Golden Dawn correspondences. Putting tarot cards, Cabbalistic texts, and astrological signs together, the leaders came up with a correspondence of the twelve signs to twelve cards arranged by their numbers. Writing it down, the Justice card was correlated with the sign of Leo (lion) and the Force card with the sign of Libra (scales). This, however, looks strange because scales appear in the Justice card, and a lion appears in the Force card.

The Golden Dawn leaders believed that the original tarot possessed a perfect order and that this anomaly reflects some mistake that crept in during the ages. To set it right, they switched the two cards. In their system Justice became eleven with a correspondence to Libra, and the Force, which they renamed Strength, became eight with a correspondence to Leo. This modified numbering became the standard for all new decks in the English school.

Ladder of Creation

Why is it at all important to know the true ordering of the cards if we can place them anyway in the order we wish? The answer is that both schools believed that the ordering of the cards was not arbitrary. Rather, there was some message or story that the suit sequence was meant to express.

Many tarot interpreters, in their quest to figure out this message, were influenced by Neoplatonist philosophy. Neoplatonism is a set of beliefs that appeared in the first centuries BCE, was later revived in the Renaissance, and also influenced the Jewish Cabbala. According to the Neoplatonist view, the world was created in a series of “emanations,” a ladder of consecutive steps in which the divine plenitude, or light, descends. The highest level is pure spirituality, and coming down from it the light gradually becomes tangible and concrete. Finally it reaches the earthly level, which is the everyday reality of matter and action.

Some of the first French tarot Cabbalists interpreted the card sequence of the major suit as an image of Neoplatonic emanation. They considered the Magician (number one) and the following cards as a representation of the highest spiritual level. Further on, they claimed, the sequence of cards descends in the scale of emanation, finally reaching the last card of the suit, the World (number twenty-one), which represents material reality.

The leaders of the Golden Dawn further developed this idea. They arranged the cards in the form of a traditional Cabbalistic diagram, the Sefirot Tree, which describes ten aspects of the divine essence and the twenty-two paths connecting them. They saw the highest spiritual degree in the Fool card, which they put at the beginning of the deck as number zero. Therefore, in their system it appears at the top of the tree. Then, going down the tree paths, they arranged all the other cards by their consecutive numbers, finally reaching the World at the bottom.

This vision also influenced the design of new decks in the English school. For example, in the Tarot de Marseille and other traditional decks, card number one, the Magician, shows a young street illusionist in a somewhat hesitant posture. But in the Golden Dawn vision, card one should represent a high spiritual degree, and the figure was modified accordingly. In Waite’s 1909 deck the same card displays a powerful magic master who looks self-confident in his commanding authority, with the symbol of infinity hovering over his head.

Still, this reading of the suit sequence as descending from high above to earth seems problematic if we examine the card themes more closely. The first cards of the suit (with low numbers) show figures whose social role and status is clear. For example, they show a street magician, an empress, a warrior, and a wandering hermit. In contrast, the last cards show celestial bodies and nude human figures in mysterious and imaginary situations. These include, for example, a girl pouring water under the stars, an angel blowing his trumpet over three figures rising from the ground, and a dancing woman surrounded by four divine living creatures. Looking at these images, we may think that perhaps it’s the first cards that are earthly and mundane, while the last cards hint at a more lofty and mysterious level of reality.

Another clue in this direction comes from the traditional use of the cards for gaming. In old tarot games, as in most ordinary card games today, a card with a high number wins over a card with a low number. The last cards in the suit have the greatest value, beating all the cards that precede them. It is reasonable, then, to suppose that their themes are meant to represent the higher levels of reality, not the lower ones.

Such considerations motivated other authors from the French school to adopt an opposite reading. In their view, the suit described a ladder of reality levels that extends from the material to the purely spiritual. But contrary to the previous reading, the suit sequence advances from bottom to top. The first cards are earthly and the last cards heavenly, not the other way around.

Parts of the Suit

For a better understanding of the major suit sequence and its evolution, let us examine its different parts in more detail. Most of the cards at the beginning of the suit show figures with a well-defined social status or professional activity. The street magician, the empress, the pope, the warrior in a chariot, and the wandering hermit are all figures that have their place in the social world of the Middle Ages. Most of the figures in these cards are large enough to fill the whole card, and they are all dressed in a way that fits their status and occupation. Thus, at the beginning of the suit we can see people living in normal human society.

Later on in the suit we see allegorical figures of virtues cherished by medieval Christian society: Justice, Force, and Temperance. The figures are still large and fully dressed, but now they represent general ideas and not concrete people. Their actions, such as holding a lion by the mouth or the act of pouring liquid between two pots, also seem more like symbolic representations rather than things that real people actually do.

To these we can add another allegory: the Wheel of Fortune, which is differently designed and shows a traditional symbol of ups and downs in social position. Together these cards can represent the two basic concepts of virtue and fortune, which are very typical in Renaissance thinking. Renaissance scholars debated the question of whether virtue, which is a person’s moral quality, or fortune, which is capricious luck, is more important in human life. Thus, although these four cards show abstract concepts rather than particular people or social roles, they still operate in the earthly sphere of human life.

The next part of the suit does not refer to social positions or accepted norms. Instead, we see disruptive and challenging cards that are detached from the common social order. The figures in these cards have no status marks, their actions seem mysterious or supernatural, and some of them are nude. The Hanged Man shows a man in an unusual situation, and it is unclear whether it expresses suffering or a choice to mortify himself. Card 13 shows a skeleton with a sickle in a field of amputated limbs. The Devil card, with an insolent bisexual body and two tied imps, mocks the conventional norms. Even the Tower card, which at first sight might seem to be a realistic image of lightning hitting a tall structure, rather hints at “fire from heaven” with the mysterious reference to God’s house in its title.

Toward the end of the suit we see another kind of change, not only in the themes but also in the structure of the cards. Now they are vertically divided between some action on the ground and some object or figure in the sky. The human figures are smaller, and many of them are partially or fully nude. In contrast to the concrete activities or the simple allegories at the beginning of the suit, it is now unclear what exactly the figures are doing and why they are doing it. Who is the nude girl in the Star card, and why is she pouring water into the river? What is the relation between her and the star that gives the card its name? And what about the two semi-nude children under the sun or the two dogs and the crustacean under the moon? All of these are far removed from the common world of practical life and simple allegories. Instead, they look mysterious, mythological, and dreamlike.

As in any pattern in the cards, here too there is no uniform and orderly development. Rather it is a complex story with twists, jumps, and exceptions. The different parts of the suit interpenetrate each other, with no clear separation between them. The Lover card appears at the beginning of the suit, although its structure resembles the last part: a division between ground and sky, several small figures, and even a nude angel or Cupid. Temperance appears at the middle of the suit as a large fully dressed figure in a relaxed attitude, in contrast with the dramatic character and nude figures of its surrounding cards. And at the end of the suit, the World has a symmetric and formal structure of its own that does not resemble any other card.

Closeness and Exposure

In the first half of the major suit, almost all of the figures are dressed. Some of them are also heavily covered — for example, by shawls and coverings in the Popess card, or by armor in the Chariot card. In contrast, many figures in the second half of the suit are nude to some degree: partly nude in the Sun and the World cards, fully nude in the Devil, the Star, and Judgment cards, and naked “to the bones” in card 13. The appearance of so many nude figures in tarot is surprising, especially if we remember that the cards were designed in a conservative era.

In our society nudity is usually associated with sexuality. But the only card where nudity seems to appear in a sexual context is the Devil, whose semihuman figures are lewd and shameless rather than sexually attractive. It seems that the appearance of nudity in the cards is not about sex. Instead, it could be linked to the idea of social status. At the beginning of the major suit, the clothing not only covers the body but also tells us something about the position and the profession of the person. All the figures are dressed in a way that expresses their social occupation: armor for the combatant, a royal gown for the emperor, a simple robe for the hermit. The same is true in real life. In a traditional society there are clear rules as to who may wear what clothes, and in our society too one can usually guess people’s occupations and status by the way they dress.

Toward the end of the suit, the signs of social status disappear along with the clothing. Neither the names of the cards nor any details in their illustrations tell us who these people are and what is their social position. This removes the figures from the context of earthly life. Interestingly, along with the removal of social signifiers, a new structure appears in the card illustrations. Now they show things happening on two levels: one on the ground (earthly) and the other in the sky (heavenly).

The appearance of the sky may also signify an opening to a higher level of reality and consciousness. It is like entering the reading space or the circle of the magical ritual. We establish contact with higher spheres by letting go of our mundane social identity and our defenses, so that we stand exposed in our mysterious existence as human beings. This may be the reason why in many cultures it is common to perform rituals of magic in the nude or in a uniform and simple dress that avoids all distinctions of social status.

When people enter a reading they become exposed, revealing intimate details of what goes on in their life and mind. This is one of the most impressive features of tarot reading: how quickly and intensively people open up and share contents that they usually keep sealed and hidden from others and sometimes also from themselves. But doing so, they expose themselves as human beings who share the same worries and concerns regardless of social status, wealth, or level of education. In front of the mysterious forces that we can feel through the cards, we are all just plain humans. The nudity of the figures may be just the cards’ way of reminding us of this.

In a reading nudity can also be part of the symbolic language of the cards. It can symbolize exposure, openness, and the removal of defenses and barriers. The association of nudity with a heavenly level in the cards can also signify openness to messages from higher spheres. In a negative sense it can be interpreted as dangerous exposure, vulnerability, and defenselessness. On the other hand, tight and heavy clothing can signify suspicion, closure, difficulty to let go, necessity to keep up defenses, and self-preservation.

The landscape in the card illustrations can also reflect the opposition of open and closed. An open field expresses exposure and removal of barriers. Walls and other obstructing constructions signify defenses and blocking. We can interpret the clothing or the nudity of a figure in terms of attempts to keep oneself protected or to become exposed, while the nature of the surrounding landscape can signify the amount of openness or closure that the environment provides.

As with any pattern in the cards, the interplay between closed or dressed and open or nude is not linear and uniform. Starting around the middle of the suit, after every open or nude card there is a card with blocking structures or dressed figures, and vice versa. In the Hanged Man (12) the figure is dressed and blocked from all sides by a wooden frame. Card 13 presents extreme nudity to the bones, and card 14 shows the figure of Temperance dressed to its neck. Card 15 presents the Devil and his imps brazenly nude, while card 16 shows a brick construction and clothed figures.

The Star (17) again presents free and flowing nudity in an open field, while the Moon (18) shows a blocked landscape with sealed towers. But now a third option appears, a sort of fusion between open and closed, with the low wall and the partial nudity of the Sun card (19). Judgment (20) again shows nude figures, and here even the earth and the sky open up to each other. The suit ends in the World card (21) with a new combination of open and closed: a nude figure partially covered by a light scarf and dancing inside a soft protective garland.

The Fool’s Journey

We can’t know for sure the intentions of the original creators of the tarot. But if they did have some Neoplatonic ideas in mind, it seems more likely that they meant to indicate a progression from the mundane to the heavenly and not the other way around. Examined in this way, we can interpret the sequence as a dynamic story of personal evolution or as an initiation quest. The story begins with a person’s awakening from being enclosed in the earthly world of social status and material possessions. The journey passes through self-trials and the endurance of hardships, which leads to a full realization of human existence with spiritual awakening, openness, and self-exposure.

In the New Age movement this reading became popularly known as “the Fool’s journey.” The idea is that the numbered cards of the suit represent consecutive stages of a spiritual quest. Only the exceptional Fool card does not seem to represent any particular stage. Instead he is the traveler himself, the person who is going through the journey. Step by step he advances through the stages signaled by all the other cards, finally reaching his full realization with the image of the World.

This idea is best exemplified with the Tarot de Marseille, in which the Fool card is exceptional because it has no number. This is different from the Golden Dawn vision that saw the Fool (0) as the final goal of the journey, not as the person going through it. We may also see a hint of this idea in the derivation of the name “tarot” from “the Fool’s cards.” In the cards’ language, maybe the Fool carries in his bag all the other cards, taking out each one as he reaches corresponding stations along the way.

Following the first introduction of this idea by the New Age tarot writer Eden Gray, there were many versions of the Fool’s journey. Here is a version inspired by the Conver-CBD images of the Tarot de Marseille. It is not meant to be “the true story” behind the suit sequence, nor is it the universal model to be followed by any spiritual seeker. The cards can be rearranged in many possible combinations, and anyone can find their own way through them. Instead, the narrative of the Fool’s journey is a way to put in our mind the idea of the major suit sequence as a coherent story, with a direction, sense, and purpose, before going into the details of each separate card.

The Fool, The Wheel of Fortune

The Wheel of Fortune, with the number ten (which is significant in numerology), can be regarded as a turning point of the story. The rotating wheel can symbolize the cycles of normal life with their ups and downs. For example, it can represent the repeating cycle of working days from waking to sleep. It can symbolize a week or a year, with their regular cycles of holidays and communal gatherings. It can also stand for the cycle of generations in a family. And in Buddhist terms we can see it as samsara, the repeating cycle of birth and rebirth.

The cards with numbers lower than ten can represent stages of growing up in normal society. The Magician, as the number one, represents the first awakening of our own individuality. His tools spread upon the table can stand for capacities and potentials that may or may not be realized. The four following cards are significant figures of authority that influence our early years: parents in the Empress (3) and the Emperor (4), teachers in the Popess (2) and the Pope (5).

The Magician, The Popess, The Empress, The Emperor, The Pope

The Lover card (6), with its unusual design for this part of the suit, turns our attention back to the individual now coming out of his childhood years. The figure standing between two women possibly indicates the choices that we make as young adults, with consequences that accompany us for the rest of our lives. And the appearance of the heavenly Cupid in the card may symbolize the uplifting and near-mystical quality of our first encounters with love.

The Lover

We can see the next three cards as a single unit. The Chariot (7) and the Hermit (9) can represent two opposites. The Justice card (8), with its scales and sword, can be weighing them one against the other, as well as cutting and choosing between them in a particular moment. For example, we can see the serene adult figure in the middle as striking a balance between the young and old figures on its two sides. The Chariot may symbolize youthful vanity and the desire to go out and conquer the world, while the Hermit stands for maturity and a cautious outlook based on experience. Alternatively, the Chariot can symbolize an occupation with external achievements, while the Hermit indicates an inner quest for wisdom and self-awareness. The Justice card can also represent the laws and norms of society, which govern both our external actions and the shaping of our inner values.

The Chariot, Justice, The Hermit

All this is part of human life in normal society. The quest for awakening to a higher level of existence starts only after the Wheel of Fortune card. The Force (11), with a woman taming a lion whose head comes out of her own pelvis, can signify a moral battle with oneself in order to control one’s animal desires. The mysterious Hanged Man (12) carries his own self-

examination to the extreme. By hanging himself upside down, he is putting in question all his previous assumptions about what is above and what is below. He also takes a risk by giving up the solid base of accepted reality as he hovers above an abyss with his hands held behind his back.

Force, The Hanged Man

The next group of cards shows dramatic challenges and trials with a transformative effect. The dark appearance of card 13 makes it stand out among all the other cards. Even its missing title may hint at things too scary to be named. The sturdy skeleton figure, the sharp edge of the scythe, and the severed heads and limbs indicate disintegration and irrevocable change. The crowned head on the right can symbolize past authority figures and guiding values that are now thrown down and trampled over.

Card 13, Temperance, The Devil, The Tower

The Temperance card (14) appears as a temporary relief with gentle reconciliation and appeasing of tensions. It may signify taking some time to patiently work out the outcome of the extreme trial in the previous card. It may also be needed before facing the lascivious paradoxes and the bawdy anarchism of desires stemming from the dark lower levels of the Devil (15). In the Tower (16) we can see the collapse of old established structures and values, but also an opening to higher forces coming from above. Also, it can represent giving up high-rise, vain illusions and coming down to the humble but fertile ground of actual existence.

The three following cards can signify together an awakened state that comes after those trying experiences. Now life on earth is infused with an awareness of higher levels, symbolized by the appearance of heavenly bodies above. But we can also see it as another evolution: from the naive full exposure in the Star (17) through the confrontation with deep and obscure layers of the mind in the Moon (18) and finally the arrival at the balanced and restrained acceptance of heavenly bliss in the Sun (19).

The Star, The Moon, The Sun

The last two cards, whose imagery is taken from the traditional Christian vision of final redemption, may indicate the desired state of spiritual consciousness at the end of the quest. In the Judgment card (20) we see the heaven, the earth, and the abyss opening toward each other. The spiritual vertical axis meets the earthly horizontal axis, and the three figures can bring to mind a psychological reparation of the initial relations with the parent figures. The balanced and symmetric World card (21) is the final station of the journey, with all the elements finding their place in perfect harmony.

Judgment, The World

Still, this sublime vision can also be a trap. From a perfect situation there is nowhere to go, no place for further improvement. Perhaps it is better to think of the Fool’s journey not as a straight line but as a circle repeating itself on a higher level each time. With this vision we can interpret the strange oblong shape between the Magician’s table legs both as an opening from which he is born and as an emptied form of the World’s wreath, now perceived as a womb. As the World gives birth to the Magician, it is time to start the journey once again.

We may also think that the very image of the cards as fixed stations on a linear track is too restricted. Maybe it is better to see it as just one possible story among many. A richer image appears in a 1932 fantasy novel by Charles Williams called The Greater Trumps (an old-fashioned name for the major suit cards). Williams imagines the tarot cards as three-dimensional golden figures who move incessantly in a complex dance that reflects the great dance of life. Looking at the dance of the tarot figures, one can understand and predict the corresponding movements of real life events.

Amid all the dancing figures, only the Fool appears to be standing motionless. It is said that whoever understands the meaning of this fact will decipher the great secret of the tarot. The secret as such isn’t revealed in the book, but we can find a hint of it in one of the female characters, who is an enlightened person with all-encompassing love. Only she sees the Fool constantly jumping to and fro, disappearing and reappearing once again, each time filling the empty gaps between the other cards.

Hebrew Letters

Many writers in both the French and the English schools believed that the twenty-two cards of the major suit corresponded to the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet. This correspondence was significant for them because traditional Cabbalistic texts attach spiritual meanings and magical powers to the Hebrew letters. But each of the two schools had their own method for establishing the exact correspondences.

The founder of the French tradition, Eliphas Lévi, matched the first letter, alef, to the Magician, which is the first card in the suit. Lévi also saw the shape of the Magician’s body, with one arm raised above and the other below, as hinting to the shape of the Hebrew letter alef. He matched the second letter, bet, with the Popess card (number two), and so on, proceeding by the standard ordering of the Hebrew alphabet.

This correspondence creates other interesting links between the cards and the letters, some of which Lévi may have been aware of. The letter kaf was matched to the Force card. In Hebrew kaf means “palm,” like the palms holding the lion in the card. The Hanged Man in card 12 with his bent leg resembles the shape of the letter lamed. The letter mem was matched to card 13, which is sometimes called Death (mavet in Hebrew). The Devil got samekh, the initial letter of Samael, which is the devil’s name in Hebrew. The body and the legs of the falling figure on the left of the Tower card are similar to the shape of the letter ayin. Lévi also put the Fool at the place before the last, matching it with the letter shin. This is the initial letter of shoteh, which in Hebrew means “fool.” Tav is the initial of tevel, which in Hebrew means “the world.”

The English school of tarot adopted a different system. As the Fool card was moved to the top of the suit, it was matched to the first letter, alef. The rest of the cards were matched according to the sequence order, which made bet correspond to the Magician, gimel (the third letter) to the Popess, and so on. This correspondence may seem strange to those who know gematria, the traditional notation of numbers by Hebrew letters, which is very important in the Cabbala. For example, bet in gematria is two, but in the Golden Dawn method it corresponds to card number one. Nevertheless, the Golden Dawn leaders adopted it. Later, Crowley further modified their correspondence by switching between the letters of the Emperor and the Star.

The result is that there are different ways of matching the Hebrew letters with the tarot cards. This is a bit confusing because in several new decks the Hebrew letters are explicitly written on the cards. As some of these do it by the English system and others by the French system, different decks show different letters on the same card.

For an open reading on personal issues with the Tarot de Marseille, the question is not so important, as the Hebrew letters don’t actually appear on the cards. Therefore, the whole issue can just be ignored. Still, readers who speak Hebrew or know the Cabbala can use the correspondences as an additional layer of meaning for the cards. For example, there are many who believe that a person’s name has an influence on their life. To understand the influence of a specific name, we can write it down in Hebrew, lay down the corresponding cards in a row, and read them. A similar method can be used with Cabbalistic letter combinations, which are supposed to have positive effects. Doing this, we can create a luck-bearing talisman made from tarot cards. Alternatively, a card appearing in a spread can be given a specific meaning by looking for a person or a place whose first initial is the corresponding Hebrew letter.

If we wish to use a Hebrew letter correspondence, which system should we adopt? A reasonable choice would be to go by the deck we are using. With the Tarot de Marseille and other French-school decks, we may use Eliphas Lévi’s system of correspondences. With decks from the English school, such as Waite’s, we may use the Golden Dawn system. If you don’t know to which school your deck belongs, it’s a good idea to check the numbers of Justice and Force. In the French school Justice is 8 and Force is 11, and in the English school it’s the other way around.

The following table lists all the major suit cards with their titles, numbers, and the corresponding Hebrew letters in both schools. The first items for each card are as in the French school: card number (in modern numerals), card name (as in this book), card number as a roman numeral, title (as in Conver’s Tarot de Marseille), and Hebrew letter and glyph (by Lévi). The English school items follow, including the number and the Hebrew letter (standard Golden Dawn). Note that in the Tarot de Marseille, card 13 has no title and the Fool has no number.

table 1: major card titles and hebrew letters

|

card |

french school |

english school |

|||||

|

1 |

The Magician |

I |

Le Bateleur |

Alef |

|

1 |

Bet |

|

2 |

The Popess |

II |

La Papesse |

Bet |

|

2 |

Gimel |

|

3 |

The Empress |

III |

L’Imperatrice |

Gimel |

|

3 |

Dalet |

|

4 |

The Emperor |

IIII |

L’Empereur |

Dalet |

|

4 |

He |

|

5 |

The Pope |

V |

Le Pape |

He |

|

5 |

Vav |

|

6 |

The Lover |

VI |

L’Amovrevx |

Vav |

|

6 |

Zain |

|

7 |

The Chariot |

VII |

le chariot |

Zain |

|

7 |

Khet |

|

8 |

Justice |

VIII |

la justice |

Khet |

|

11 |

Lamed |

|

9 |

The Hermit |

VIIII |

l’hermite |

Tet |

|

9 |

Yod |

|

10 |

The Wheel of Fortune |

X |

l’a rove de fortvne |

Yod |

|

10 |

Kaf |

|

11 |

Force |

XI |

la force |

Kaf |

|

8 |

Tet |

|

12 |

The Hanged Man |

XII |

le pendu |

Lamed |

|

12 |

Mem |

|

13 |

Card 13 |

XIII |

|

Mem |

|

13 |

Nun |

|

14 |

Temperance |

XIIII |

temperance |

Nun |

|

14 |

Samekh |

|

15 |

The Devil |

XV |

le diable |

Samekh |

|

15 |

Ayin |

|

16 |

The Tower |

XVI |

la maison diev |

Ayin |

|

16 |

Pe |

|

17 |

The Star |

XVII |

letoille |

Pe |

|

17 |

Tsadi |

|

18 |

The Moon |

XVIII |

la lune |

Tsadi |

|

18 |

Kof |

|

19 |

The Sun |

XIX |

le soleil |

Kof |

|

19 |

Resh |

|

20 |

Judgment |

XX |

le jugement |

Resh |

|

20 |

Shin |

|

21 |

The World |

XXI |

Le monde |

Tav |

|

21 |

Tav |

|

|

The Fool |

|

le mat |

Shin |

|

0 |

Alef |