5

THE CONQUEST OF IRAN

The Zagros mountains rise steeply in a series of folds from the flat plains of Mesopotamia.

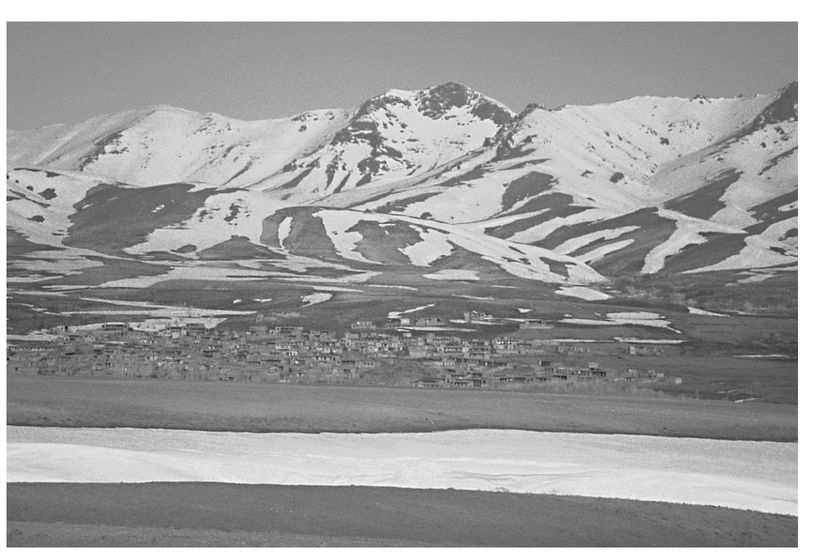

1 The foothills are green and friendly in the spring, and successive rulers of the rich flat lands of Iraq have used them to find some coolness and an escape from the heat of the plains. The Sasanian kings had loved their palaces here, and later the caliphs of the Abbasid dynasty in the eighth and ninth centuries liked to come here for the hunting. The higher mountains are much more barren and there is snow in the winter, blocking most access between Iraq and Iran. There are small fertile plains within the folds of the mountains but much of the land is fit only for use by tribes of transhumant shepherds, mostly Kurdish-speaking at the time of the conquests. They are the ancestors of those Kurds who still inhabit the mountains of north-west Iran and south-eastern Turkey.

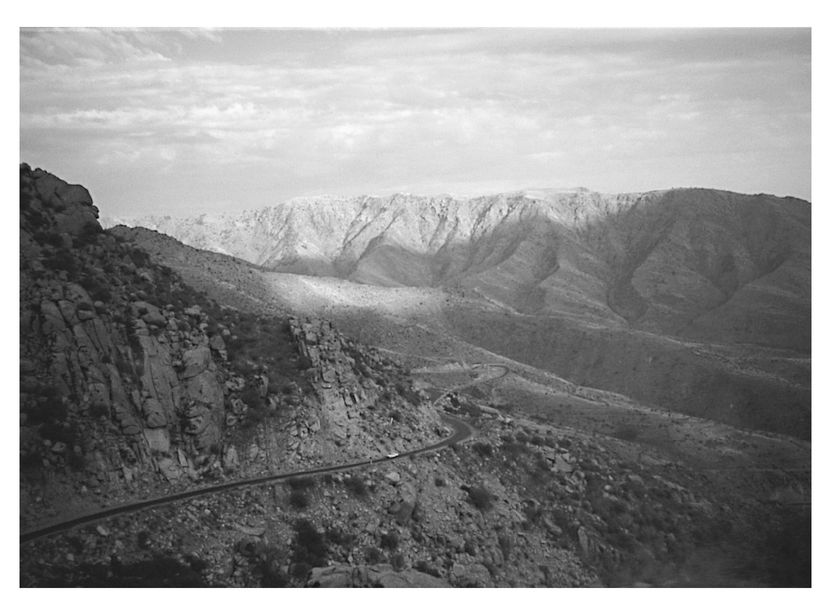

The ridges of the Zagros run parallel to the edge of the plain, one formidable obstacle after another. Apart from shepherds’ paths, there are only two major routes through the mountains. The most important of these was the Great Khurasan Road, the series of valleys and passes that led from Hulwān in the Iraqi plains, past the Sasanian palaces and gardens at Qasri Shīrīn and Daskara, and the rock-cut arch at Tāqi Bustān, with its spring-filled pool and relief sculptures of the Sasanian king hunting. From here the road wound on up through narrow defiles in the plain to Bisitun. Here, a thousand years before the Arab armies passed this way, the great Darius had set up a trilingual inscription, on a vertiginous site overlooking the road in the plain far below. It was unlikely that anyone at this time could understand the ancient languages, Babylonian, Old Persian and Elamite, carved in the old cuneiform script, but they may have been able to pick out the image of the king, sitting enthroned while his vanquished opponents were paraded before him. This was a route that great kings had passed along for centuries, leaving their mark on the main artery of the Sasanian Empire. Beyond the plain at Bisitun, the road wound up the steep pass above Asadabad before reaching the plateau. Here the lands opened out, the mountains receded and the traveller reached the ancient city of Hamadan.

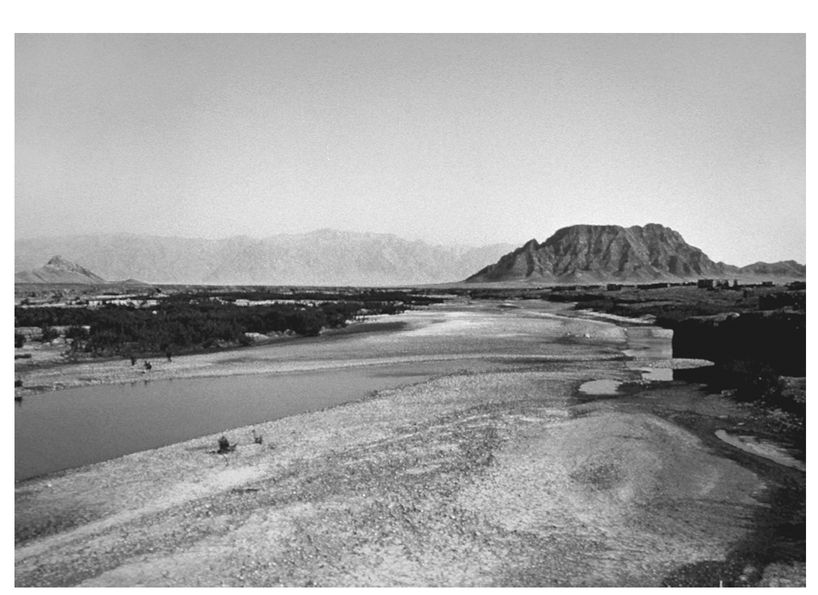

The other route from plain to plateau lay far to the south. The road passed through the flat and fertile lands of Khuzistān around the head of the Gulf, crossing the Tāb river on the long Sasanian bridge at Arrajān, before winding its way through the mountains to Bishapur, the capital of Shapur I and Istakhr, the ancient capital of Fars. The route was longer than the northern road, and fiercely hot in the summer, but it ran through well-watered valleys and was seldom blocked by snow. Of course, the traveller or invader from Arabia could also cross the Gulf by boat and arrive at a little port like Jannāba on the scorching coast, then make his way up through the mountains. It was by all these routes that the Arab invaders penetrated the interior of Iran.

The Iranian plateau itself provides few obstacles to the movements of armies. The centre, to be sure, is occupied by a series of salt deserts which are virtually impassable, but to both north and south there are wide, flat plains between the mountain ranges. There is water to be had and, especially in the spring, grazing for animals. The Arab armies were able to move through these landscapes and cover large distances with impressive speed. This enabled them to achieve overlordship of the vast areas of the Iranian plateau in a very short period of time, the eight years from 642 to 650. It also meant that much of the conquest remained very superficial. They established control over most of the main routes and the principal towns probably had Arab tax collectors protected by a small military force. The only major Arab settlement in the seventh century, however, was in Merv on the north-eastern frontier. Many mountainous areas were effectively unscathed by the conquests, their lords simply arranging to pay a tribute to the Muslim administrators.

The final defeat of Persian forces on the plains of Iraq might have been the end of the fighting. There would have been a certain logic for the Muslim forces in stopping and consolidating at least for a while, and there are hints in the sources that this option was discussed among the Muslim leadership. Iraq was an integral part of the Sasanian Empire, however, and no self-respecting king could simply abandon it to the enemy. The young Yazdgard III, now intent on establishing his power after the political chaos that had followed the death of Chosroes II in 628, was determined to recover his control of the rich lands of the Mesopotamian plains. He had fled far to the east to escape the invaders, but he now began to try to rally support to prevent them from reaching the Iranian plateau. Letters were sent to all the provinces of western and northern Iran and troops were told to muster at the little city of Nihāvand, on a side road off the main Zagros highway. Nihāvand itself was a small but ancient country town famous for the production of saffron and the manufacture of perfumes. The position was probably chosen because the open plains and good grazing made it a suitable place to assemble a large number of troops.

The accounts of the Nihāvand campaign

2 of 642 begin with a series of letters from the caliph Umar to Kūfa and Basra, ordering that armies should be assembled. The most enthusiastic recruits in Kūfa were drawn from those who had recently arrived from the Arabian peninsula and had not had the opportunity to distinguish themselves in the earlier fighting or acquire booty; this new campaign would give them the chance to make up for lost time.

3The Muslim armies gathered on the old Khurasan road and the horses were pastured at the Meadow of the Castle (Marj al-Qal

ca), where the Abbasid caliphs later kept their stud farm. They then marched on towards the Persian army at Nihāvand, about 100 kilometres away, without encountering any resistance.

4 Meanwhile another force was ordered to station itself on the borders between the provinces of Fars and Isfahan to prevent the Sasanians sending reinforcements from the south.

5According to the main Arabic sources, the invaders found the Persian army drawn up on the near side of a ravine, which was later to prove fatal to many of them. The Arab army is said, plausibly, to have numbered 30,000 men, the Persian army three or four times that, an exaggeration typical of the Arab chronicles.

6 Like the Arab forces, the Persian army had been swollen by volunteers from all the neighbouring areas who had missed the battle of Qādisiya and the fighting in Iraq and who now wished to prove themselves. The army was drawn up in the conventional way, with the commander, Fayzurān, in the centre and two wings on each side. As in other accounts of battles, we are told that the Persian troops were bound or chained together so that they would not flee

7 and that they scattered caltrops on the ground behind them, again to stop the cavalry escaping. The Arab historians loved to make the contrast between the Muslim troops, inspired by religious zeal, and their servile opponents, coerced into fighting. There are no Iranian sources to give their point of view.

The Arab army halted and the tent that was to serve as a command post was pitched. The Persians had fortified themselves behind trenches. The Muslim armies attempted to storm them but without much success, and the disciplined Persians emerged from their fortified posts only when it suited them. After a few days, the Muslim leaders met in a council of war. Again it is typical that the Muslims are presented as acting by consensus after calm deliberation, perhaps an implied contrast with the authoritarian command structure of their opponents. In the end it was decided that the Arab cavalry would advance and taunt their opponents and make as if to attack the trenches. They then withdrew and gradually lured them from their prepared positions in search of booty. Meanwhile the main Muslim army was kept in check. Despite protests from the more restless members of the army, the commander, Nu

cmān b. Muqarrin, kept them back until the day was well advanced and it was almost dark, claiming that this had been the Prophet’s preferred time to do battle. He made his rounds of the troops on his brown, stocky horse, stopping at every banner to exhort his men. He told them that they were not fighting for the lands and booty that they saw around them but for their honour and their religion. He also reminded them of their colleagues back in Kūfa, who would suffer grievously if they were defeated. He concluded by promising them ‘one of two good things, everlasting martyrdom and eternal life, or a quick conquest and an easy victory’.

8When they finally did attack the enemy, victory seems to have come quickly. As usual, most of the army fought on foot with drawn swords. Soon the ground was soaked in Persian blood. The horses began to slip and the Muslim commander, Nucmān, was thrown and killed. Despite this, the Muslims continued to advance. The Persians began to flee, and in the gathering darkness many of them lost their way and plunged to their deaths in the ravine. When the great Arab encyclopaedist Yāqūt came to compile his geographical dictionary in the early thirteenth century, 600 years after the event, the watercourse was still remembered as the place where the Persian army had been destroyed and the Iranian plateau opened up to Muslim conquest.

The surviving Persians, including Fayzurān, attempted to flee over the mountains to Hamadan but their progress along the narrow mountain paths was delayed because the road was full of a caravan of mules and donkeys carrying honey. Fayzurān himself attempted to avoid his pursuers by leaving the track and climbing over the mountains on foot, but the Muslims were soon hot on his trail and he was killed defending himself.

9The surrender of the towns soon followed the military victory. Immediately after the battle the invaders surrounded the little city of Nihāvand itself. They had been there only a short time when the Herbadh, the chief Zoroastrian priest in the city, came out to begin negotiations. He had a prize to offer, a large quantity of gems that the king had left there as a reserve for emergencies. He offered to hand this over in exchange for an

aman, a guarantee of security for life and limb for the inhabitants. This was duly accepted and the city passed into Muslim rule without any further conflict.

10According to one story,

11 the treasure consisted of two chests of pearls of immense value. When the caliph Umar was told of this, he gave orders, following his usual policy, that the pearls should be sold for cash and the proceeds divided up among the Muslims. Accordingly the contents of the chests were sold to a speculator, a young man from the Prophet’s tribe of Quraysh called Amr b. al-Hurayth, who paid for them out of the stipends that had been granted to him and his family. Having made his purchase, Amr then went to Kūfa and sold one of the chests for the same sum he had originally paid for both; the other chest he kept for himself, and ‘this was the first part of the fortune Amr amassed’. We can see here the process of de-the-saurization, the converting of treasure into cash to pay the troops, and how shrewd, even unscrupulous men in the early Islamic elite could exploit the process to make fortunes.

The survivors of the Persian army had fled through the mountain to Hamadan pursued by an Arab army of some twelve thousand men. Hamadan was a much bigger prize than Nihāvand.

12 A very ancient city, it was known to the classical geographers as Ecbatana and had been the capital of Media. A bleak, upland city, it lay at the eastern end of the main road through the Zagros passes and had been an important political centre since its foundation, allegedly in the eighth century BC. At the centre of the city lay an old hilltop fortress. When the city was founded it was said to have had seven lines of walls, each of a different colour, the innermost two being plated with silver and gold.

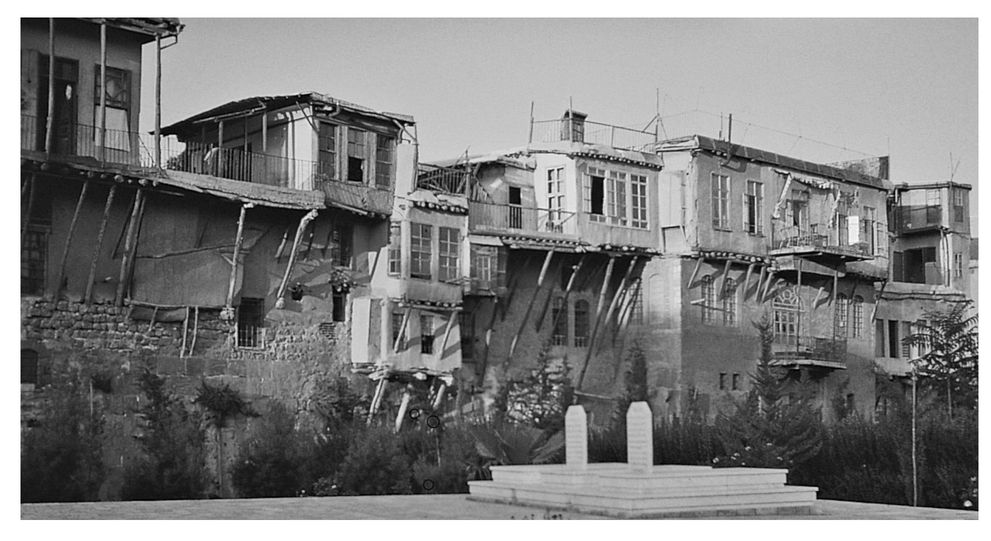

13 There is no hint that this ostentatious opulence survived to the Muslim conquest, when the walls of the citadel seem to have been made of common clay. Hamadan was also famous as the residence of Esther, the Jewish wife of Xerxes I (486-65 BC) and eponym of one of the books of the Apocrypha: her tomb is still shown to visitors. The town may have been in decline by this time: the Arab geographer Ibn Hawqal, writing 300 years later, says it had been rebuilt since the Muslim conquest.

In the event, the fortifications proved to be of little use. The commander of the garrison was Khusrawshunūm, who had already failed to hold Hulwān against the invaders. Now he made terms for Hamadan and the city surrendered peacefully.

The collection and division of the spoils followed next. As usual the Arabic sources discuss this in great detail - the 6,000 dirhams a mounted warrior was given, the 2,000 for each foot soldier. Shares were also paid to those men who had remained behind at the Meadow of the Castle and other points along the road. The fifth was retained for the government and forwarded to the caliph Umar in Medina. As always, the sums of money must be taken with a large grain of salt, and the emphasis on fair shares for all probably reflects the enthusiasm of later commentators for finding examples of perfect practice in early Islam rather than any historical reality.

The next objective of the Arab armies was Isfahan,

14 for, as a Persian renegade is said to have explained to the caliph Umar, ‘Fars and Azerbaijan are the wings and Isfahan is the head. If you cut off one of the wings the other can still work but if you cut off the head, the wings will collapse. Start with the head!’

15 Since the sixteenth century, Isfahan has been famous for its tiled mosques, palaces and gardens, but the Isfahan conquered by the Muslims was a very different place. It was essentially a well-watered plain between the eastern flanks of the Zagros mountains and the great desert of central Iran. In the plain there were a number of villages and a fire-temple on an isolated outcrop of rock. One of the villages, called Yahūdiya or Jewry, was an unfortified settlement inhabited by Jews which was later to become the nucleus of the medieval and modern city. At this time, however, the only fortified settlement was the round city of Jayy, which lay on the banks of the Ziyanda Rud river some 4 kilometres from the present city. Local legend said that Jayy had been built by Alexander the Great but the walls had been rebuilt in Sasanian times and had four gates and 104 round fortified towers. According to one local source, Jayy was not a real inhabited city but rather a fortress and place of refuge for the inhabitants of the villages of the area.

16 The fortifications must have been impressive, though nothing survives on the site except for the piers of the Sasanian bridge across the river.

Once again, the fortifications were never put to the test. The local governor led his troops out to meet the advancing Arabs. There is said to have been an inconclusive individual trial by combat between him and the commander of the Arab forces before the Persian made an agreement, in which the inhabitants were allowed to remain in their homes and keep their property in exchange for the payment of tribute. The text of the treaty is given in the sources. It takes the form of a personal agreement between the Arab commander and the governor. Tribute would be paid by all adults but it would be set at an affordable rate. The only other important provisions were that Muslims passing through should be given hospitality for a night and given a mount for the next stage of their journey.

Thirty diehard adherents of the Sasanian regime left the town to go eastwards to Kirman and join the Persian resistance, but the vast majority accepted the new dispensation.

17 The occupation seems to have been conducted with a light touch. There was no violence or pillaging. Disruption to the existing community was limited; there was no large-scale Muslim settlement and no major mosque was constructed for the next century and a half.

Sometimes the Arabs were welcomed by the local inhabitants. In the little town of Qumm, later famous as one of the great Shiite shrines of Iran, the local ruler, Yazdānfar, welcomed Arab settlers, giving them a village to settle in and supplying them with lands, beasts and seeds to begin agriculture. The reason for his generosity was that the people of Qumm had been suffering from raids by the Daylamite people of the mountains to the north and Yazdānfar hoped that the Arabs would defend the community in which they had made their homes against the depredations of these raiders. In the first generation this seems to have worked and relations were more or less harmonious. Later, as the number of Arab immigrants increased, there were tensions over landownership and above all water rights which led to violence, but the initial ‘conquest’ of the area was largely peaceful.

18The Muslim armies pressed on along the road that led to Khurasan and the east. After defeating an army of Daylamites and other mountain people attempting to block his progress at Wāj al-Rūdh,

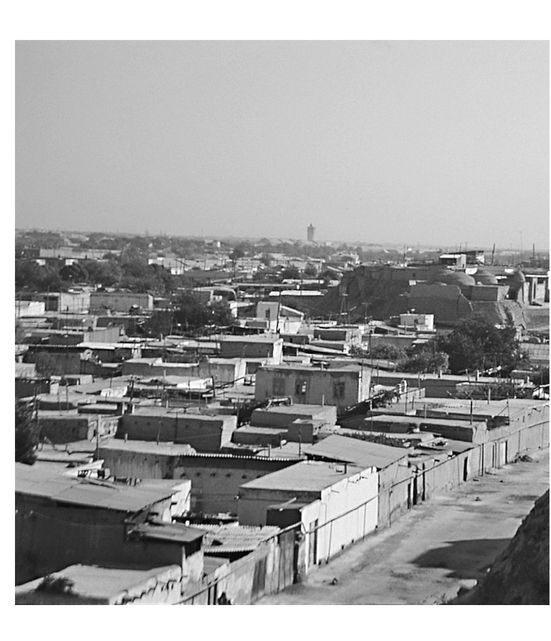

19 he headed for Rayy. Rayy lay just south of modern Tehran, which was no more than an obscure village until it was made the capital of Iran by the Qajar dynasty in the late eighteenth century. Rayy was known to the ancient Greeks as Rhages. It was already established when Alexander the Great passed through in his pursuit of Darius III, and it was rebuilt as a Macedonian polis by Seleucus Nicator in about 300 BC. He called it Europos after his own birthplace in Macedonia but, as so often, it was the old name which stuck. In around 200 BC it was taken by the Parthians and became the summer residence of the kings. Isidore of Charax describes it as the greatest city of Media, and its strategic position meant that it continued to thrive under the Sasanians.

Rayy was of immense strategic importance. To the south lay the great desert of central Iran, waterless, encrusted with salt and virtually impassable. To the north, the mountains of the Elburz range rose with dramatic suddenness from the plains. It was the water from these mountains which gave birth to the two small rivers that watered the city before they lost themselves in the desert margin to the south. Any army wanting to pass from western Iran to Khurasan and the east had to use this narrow belt of watered, fertile land and pass the city of Rayy. Siyāvush, the governor of this important place, came from one of the most aristocratic families in Iran, the Mehrans, who had a hereditary position as lords of Rayy.

19 He was the grandson of no lesser man than the great Bahrām Chūbin, one of the most respected generals in the Sasanian army, who tried to usurp the throne from the young Chosroes II in 590. The rebellion failed as Chosroes, with Byzantine military support, regained his throne. Bahrām was killed but his family clearly maintained their control of Rayy.

The Arab armies would have found a walled city, with brick or clay houses dominated by a castle on a rocky outcrop overlooking the site. They might have expected that an assault or even a major siege would be necessary. In the event, rivalries among the Persians gave them an opportunity. The dominance of Rayy by the Mehran family was resented by the rival Zinābi family and the leader of the Zinābis came to meet the Arab armies at a village on the main road from Qazvin to the west of the city. He made an offer to lead some horsemen inside the walls by a back way. The Muslims mounted a night attack. At first the Persians stood firm but then the horsemen within the city charged them from behind, shouting the traditional Muslim war cry, ‘

Allhu Akbar’. The resistance crumbled and the invaders soon took possession of the city. There was obviously a considerable amount of looting, and it was said that as much booty was taken from Rayy as had been from the imperial capital at Ctesiphon. The Arab conquest resulted not so much in Arab occupation as in a reshuffle among the Persian elite. The Mehran family lost their authority and their quarter of the city, later known as the ‘Old Town’, was devastated. Meanwhile Zinābi was named as governor, and even given the Persian rank of Marzban. He gave orders for the building of a new city centre and his family, including his two sons, Shahram and Farrūkhān, were in effective control of the city.

20The Arab armies continued to advance along the Khurasan road to the small piedmont city of Bistām, renowned for the fertility of its soil and the excellence of its fruit, and received the peaceful submission of the provincial capital at Qūmis.

While the Arab army was encamped at Bistām, the commander, Suwayd b. Muqarrin, began to make some diplomatic overtures to the rulers of the mountain areas to the north. From Gīlān in the west through Tabaristān and Dubavand in the centre to Gurgān in the east, the southern shores of the Caspian Sea are dominated by mountain ranges, which reach their highest point at the spectacular summit of Damavand. The mountains are very unlike most of Iran. In contrast to the open and bleak slopes and summits of the Zagros, the mountains of the Elburz range are often well wooded. The northern slopes are humid and nowadays suitable for rice- and tea-growing. The roads through the mountains are few and narrow. It was not an area that any Arab military leader would be eager to attack: they always avoided narrow mountain passes and steep valleys.

Suwayd began by making contact with the ruler of Gurgān. The lands of Gurgān lay to the south-east of the Caspian Sea. This was where the mountains met the almost limitless plains of Central Asia. It has always been a frontier area and the meeting place of the settled Iranian peoples to the south and west and the nomadic Turkish speakers to the north-east: for most of the twentieth century it was the border between Iran and the territories of the Soviet Union. Today the border between Iran and Turkmenistan runs through it. The great Sasanian monarch Chosroes I Anushirvan (531-79) built a long wall, strengthened with forts at regular intervals, from the Caspian coast 100 kilometres along the desert frontier.

Remote Gurgān had always been a semi-detached part of the Sasanian Empire, being ruled by hereditary princes with the title of Sūl. The Sūl of that time, Ruzbān, entered into negotiations with Suwayd. The two met on the frontier of the province and went around assessing what tribute was to be paid. A group of Turks were allowed to escape taxation in exchange for defending the frontier, perhaps the first time in what would become a long history of Muslims employing Turks as soldiers. The text of the treaty

21 reflects the unusual status of the province. The tribute was to be paid by all adults unless the Muslims required military assistance, which would, in that case, count instead of payment. The people were allowed to keep their possessions and their Zoroastrian religion and laws as long as they did no harm to any Muslims who chose to settle there. This was conquest in name only. The traditional ruler remained in charge, paying tax now to the Muslims rather than to the Sasanian king, but there is no indication of Muslim settlement or military occupation.

At the same time, the ruler of Tabaristān, further to the west, opened negotiations to regularize his position. Tabaristān was more inaccessible than Gurgān and was completely covered by mountains, apart from a narrow strip of land along the Caspian shore. The treaty that Suwayd made with the local ruler merely stipulated that he was to restrain robbers and bandits from attacking neighbouring areas and that he should pay 500,000 of the locally minted dirhams a year. He was not to harbour fugitives or carry out treacherous acts. Muslims would visit the territory only with the permission of the ruler.

Tabaristān was not visited by any Muslim army and, at least according to the treaty, the tribute was a global payment for the whole area, rather than a poll tax. It looks as if all aspects of government, including tax collecting and the minting of coins, remained in the hands of the local ruler. The ruler of neighbouring Gīlān to the west was granted similar terms. The ‘Arab conquest’ of these areas was so swift because it amounted to so little in real terms: the rulers may even have been paying less tax than they had in Sasanian times. The reality was that these areas remained outside Muslim control until the eighth century. The road east from Rayy remained insecure and Muslim troops going to Khurasan were obliged to use the route that led south of the Great Desert and then turned north through Sistan.

At the same time more Muslim armies were moving into Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan was the vast province at the north-west of the Iranian plateau. This was a land of strongly contrasting environments. In some areas down by the Caspian coast the land was warm and comparatively well watered. Further south and west were vast open uplands with high mountains. This was good territory for summer pasture, and much of it was probably inhabited by Kurdish tribesmen, who spent their winters in the plains of northern Iraq or the Mughan steppes by the Caspian and their summers in the upland pastures. There were few important cities here and population must have been sparse and scattered in these vast landscapes. Booty too must have been thin, with none of the allure of the rich cities of Iraq or Fars.

The first troops had set out from Hulwān under the command of Bukayr b. Abd Allāh al-Laythī.

22 It seems likely that they found the going difficult, and after the conquest of Hamadhan, Nu

cmān was ordered to send troops from his army to support him. Nu

cmān chose to delay until after he had secured Rayy. Once again, the Arabs were helped by the cooperation of an important figure in the Iranian elite. Isfandiyādh was the brother of the Rustam who had led the Persian armies in the disastrous defeat at Qādisiya, which had opened the door of Iraq to the Muslim armies. The family may have come from this area, and Isfandiyādh led the armies of Azerbaijan in a futile attempt to halt Nu

cmān’s advance to Nihāvand. He had been taken prisoner by Bukayr at the beginning of the Azerbaijan campaign and had agreed to mediate between the Arab commander and the local population. He warned Bukayr that unless he made peace with the people, they would disperse into the Caucasus and the mountains of eastern Anatolia, where they would be almost impossible to dislodge. Once again it was diplomacy which ensured the success of the Muslim armies. The details are very sparse but it looks as if there was little fighting and that most people agreed to pay tribute in return for being allowed to keep their property and their customs and religion. There is no mention of any sieges, nor does it seem that Arab garrisons were established.

The Arab armies moved on up the western coast of the Caspian Sea to the town the Arabs called Bāb al-Abwāb, the Gate of Gates, which is now called Derbent. It was here that the main range of the Caucasus mountains came down to the sea coast. At this point the Sasanians had established a fortified outpost. The long, strong stone walls still run from the sea to the spur of the mountains. Like Gurgān, this was frontier territory. Beyond the wall was nomad country, the vast plains of what is now southern Russia.

The commander of the Sasanian garrison was one Shahrbarāz. He was very conscious of his aristocratic origins and clearly had little sympathy with the people of the Caucasus and the Armenians who surrounded him. Knowing that the Sasanian regime elsewhere had collapsed, he sought instead to make common cause with the Arab leaders, entering into a series of negotiations in which it was agreed that he and his men should be exempt from paying a poll tax in exchange for military service in the frontier army. In this way the remaining elements of the Sasanian army were not defeated but incorporated into the armies of Islam. No doubt some of them soon came to convert to Islam. Interestingly, other reports show that while the Arab commanders were keen to attack the nomads beyond the wall at Bāb, the experienced Persians warned against it, saying effectively that they should let sleeping dogs lie.

23 The Arabs did launch raids north of the wall, but no permanent gains were made. In the long run, the frontier established at the wall in 641-2 has remained the frontier of the Muslim world in the eastern Caucasus to the present day.

Similar arrangements are said to have been made with the Christian inhabitants of upland Armenia, and Arab armies penetrated as far at Tblisi in Georgia, but details are sparse and it is not clear what the effect of this activity was.

Meanwhile, a completely separate campaign was under way in southern Iran. The conquest of Fars

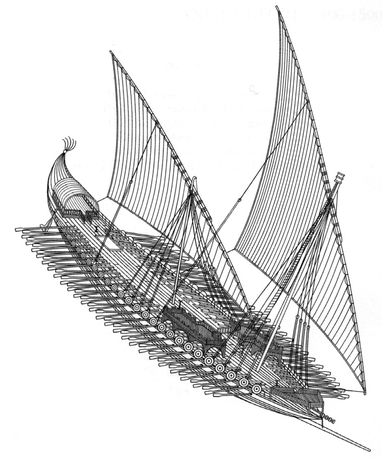

24 began with a seaborne invasion. There had always been close contacts between the peoples on both shores of the Gulf, and Oman especially had an ancient seafaring tradition and lots of sailors for whom the crossing of the usually tranquil waters between the coasts of Iran and Arabia presented no problems. At the time of the earliest conquests the Gulf was virtually a Sasanian lake, the Persians maintaining a number of small outposts on the Arabian shore. In the absence of large timbers and iron, navigation was possible in boats made of palm trunks, sewn together with thread, ancestors of the dhows that can still be seen in local waters today. It was natural that when the Arabs of Oman and Bahrain saw the success of their northern cousins against Sasanian Iraq, they too would wish to join in.

As in other areas, the first conquests immediately followed on from the ridda wars. The governor of Bahrain appointed from Medina, Alā b. al-Hadramī, apparently acting on his own initiative, took the Persian outposts on the Arabian coast. In 634 he sent a maritime expedition under the command of one Arfaja, which took an unnamed island off the Persian coast and used it as a base for raids. It seems that the caliph Umar, always portrayed as suspicious of maritime expeditions, disapproved of this exploit and the force seems to have withdrawn without achieving any permanent gains.

The next attempt was made by Uthmān b. Abī’l-Ās, who was appointed governor in 636 and was responsible for most of the conquest of Fars. He was not a native of the Gulf coast. Like many early Muslim commanders he came from the hilltop city of Tā’if near Mecca and was no doubt drafted in to ensure the control of Medina over the area. In about 639 he sent a naval expedition across the Gulf under the command of his brother Hakam. Part of his intention must have been to engage the energies of the local tribesmen and provide them with opportunities for booty, but it is also likely that Umar could see that an attack from this quarter would distract the still-formidable Persian forces from the conflict in Iraq. In particular, it would divert the energies of the Persians of Fars so that they could not join the main armies further north. Umar also ordered that the Julandā family, hereditary rulers in Oman, should provide support for the expedition. The expeditionary force was comparatively small, 2,600 or 3,000 men are the numbers given in the sources, and they were mostly drawn from the great Umani tribe of Azd. They set off from the port of Julfar on the site of the capital of the modern emirate of Ra’s al-Khayma and established themselves at the island of Abarkāwān (nowadays known as Qishm) just off the Iranian coast. It was a sea journey of some 130 kilometres and would hardly have taken more than a couple of days in favourable winds. Like their predecessors in 634, they intended to use the island as a secure base for attacking the mainland.

The local commander made peace with them without putting up any resistance, but Yazdgard III was still trying to mount a vigorous defence against the invaders. He ordered the lord of Kirman to launch an expedition from Hurmuz to retake the island, but this was defeated. The Muslims then moved across to the mainland and began raiding the surrounding areas. Not surprisingly the Sasanian Marzbān of Fars, Shahrak, set out to oppose them, but his army was defeated at Rashahr in 640 and he himself was killed. After this, in 642, when the victory at Nihāvand and the Arab conquest of Ahvaz had reduced the threat posed by the Persian army, the Muslims established a permanent base at the little town of Tawwaj, which became their misr, their military base. The city lay not on the coast itself but a few kilometres inland, where the Shapur river provided a water supply. The town was extremely hot, like all the settlements on the Persian side of the Gulf, but surrounded by palm trees. They built mosques there, presumably very simple structures of mud brick and palm. Tawwaj might have developed as a small-scale Basra or Kūfa but events were to turn out otherwise. The town continued to thrive as a commercial centre famous for its linens woven with gold thread, but its role as a military base ceased as the Muslim armies moved further inland.

Starting from Tawwaj, Uthmān b. Abī’l-Ās embarked on the conquest of the upland areas of Fars. Fars was one of the most important provinces of the Sasanian Empire. The great monuments of the first Persian dynasty, the Achaemenids, were to be found here, and the great columned halls of Persepolis were witnesses to this ancient grandeur. It was in Fars at the city of Istakhr that the Sasanian dynasty itself originated as guardians of the temple of Anahita. The first two monarchs had created new capitals here at Jūr and Bishapur, and though later kings seldom stayed there any more, it was still remembered as the birthplace of the dynasty. Yazdgard III, in his flight, had gone back to Istakhr, back to the cradle of his dynasty, to try to rally support. Geography too was on his side. This was a land of rugged mountains, narrow passes separated by grain-growing plains and salt lakes.

We have few details of the campaign that brought this important area under Muslim rule, but the campaigning seems to have met considerable resistance. Fars was a land of mountain-top castles

25 and easily defended passes. A first attempt against the capital Istakhr in 644 failed. In 647 Muslim forces, now bolstered by reinforcements from Basra, took the city of Bishapur. The uninhabited ruins of the city can still be seen today. It lies in a fertile plain at the foot of steep mountains where a river of clear fresh water tumbles through the limestone crags to the plains. Along the side of the gorge, Shapur I, the builder of the city, had ordered the carving of bas-reliefs, depicting his triumphs. At the heart of it lay a great stone fire-temple, said to have been constructed by Roman prisoners of war, captured when Shapur defeated the Roman emperor Valerian in 260. Beside that lay the subterranean temple of the water goddess Anahita. Around it spread the city itself, laid out on a grid plan like a Greek or Roman polis. The city survived the Muslim conquest but by the eighth century its population was already being drained away by the expanding city of Kāzirūn near by and the new Muslim metropolis of Shiraz. By the twelfth century, it was a deserted ruin.

In 648 the Muslims made peace arrangements at Arrajān on the main road between Iraq and the uplands of Fars and Darābjird in the uplands to the east. Darābjird was another round city, in this case with a fortress in the centre. According to Balādhurī, it was the fountain (

shadrawn) of the science and religion of the Zoroastrians, though he did not clarify what this tantalizing reference meant. It was nonetheless a religious leader, the Herbadh, who surrendered it to the Muslims on condition that the people were given the same terms and guarantees as for other cities in the area.

26By 650 only the capital Istakhr and the round city of Jūr were holding out against the Muslims. In this year the command structure was completely revised. Authority in Fars was entrusted to the new governor of Basra, Abd Allāh b. Āmir. Abd Allāh was an aristocrat from the Prophet’s tribe of Quraysh, a man renowned for his wealth and his easygoing generosity. He dug new irrigation canals in Basra and improved the supply of water for pilgrims in Mecca. He was also a daring military commander, prepared to lead his army far from their homes in Iraq to the farthest outposts of the Sasanian Empire. His appointment also meant that all the resources of the Muslim base at Basra could be devoted to the conquest of southern and eastern Iran. As usual the accounts of this final campaign in Fars are both sparse and confused, but it seems clear that there was considerable resistance in both Jūr and Istakhr. Jūr, we are told, had been raided for some time but only fell to Ibn Āmir’s troops after a dog, which had come out of the city to scavenge in the Muslim camp, showed them a secret way back in.

27After this, it was the turn of the capital of Fars. The scanty remains of the city of Istakhr are still visible today. It lies on flat ground on the main road a few kilometres north of the ruins of ancient Persepolis. It is not a naturally fortified site but was clearly walled at this time. The defenders seem to have mounted a more prolonged resistance than anywhere else. As happened in several other places, the city was said to have surrendered on terms and then rebelled or broke the agreement. It was during the subsequent reconquest that the conflict took place. According to one account,

28 Ibn Āmir’s men took the city after fierce fighting, which included a bombardment with siege engines. The conquest was followed by a massacre in which 40,000 Persians perished, including many members of noble and knightly families who had taken refuge there.

The scale of death and destruction at Istakhr seems to have been unparalleled in the conquest of west and central Iran. It was the only conflict in which siege engines are said to have been used to reduce a fortified enclosure and the only occasion on which a massacre on this scale took place. There also seems to have been a systematic attempt to destroy the main symbols of the old Persian religion, the fire-temples, and confiscate the properties: one Ubayd Allāh b. Abī Bakra is said to have made 40 million dirhams ‘extinguishing fires, destroying their temples and collecting the gifts that had been deposited in them by Zoroastrian pilgrims’.

29 Although the details are very scanty, and we have no Persian accounts to place alongside the bare Arabic narratives, it seems that there was much more resistance to the Arab invaders in Fars and especially in Istakhr than elsewhere in Iran. The role of the province as cradle and original homeland of the Sasanian dynasty may have led the local people to fight the invaders with such vigour.

Abd Allāh b. Āmir continued to push east from Fars, following hard on the heels of Yazdgard III, who had escaped before Istakhr fell. He moved on rapidly to the province of Kirman. Here the main towns, including Bam and the then capital Sirjān, fell quickly. We are told that many of the inhabitants abandoned their houses and lands rather than live under Muslim domination. Arabs came and settled in their properties.

The province of Sistan, or Sijistan, lies to the north and east of Kirman. Nowadays this is a sparsely inhabited and often lawless area straddling the Iran-Afghan border. It suffers a fierce continental climate, the daytime temperature regularly reaching 50°C in the summer, while in the winter blizzards sweep across the desolate landscape. Much of it is desert and the landscape is studded with the shapeless mud-brick ruins of ancient buildings. It has not always been so uninviting, and the present desolation of the area probably dates from the Mongol and Timurid invasions of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The province owed its prosperity to the waters of the Helmand river, which brings the meltwater of the Hindu Kush mountains of Afghanistan to the plains. Like the Murghab river at Merv and the Zarafshan in Samarqand and Bukhara, the river could be used to irrigate fertile lands before it petered out in the desert. Early Islamic travellers commented favourably on the fields and crops of areas that are now treeless wastes. Sistan took its name from the Sakas, an Indo-Iranian people who played an important role in the history of the Parthian period: mail-coated Saka cavalry were an important element in the Parthian army that famously defeated the Roman general Crassus at Carrhae in 53 BC. All memory of the Sakas had been lost by the time of the Muslim conquest, but the Sistanis retained a reputation for hardiness and military prowess, though mostly as foot soldiers.

Sistan was also important as the setting for some of the most important events in the Shahnāmah, the Persian national epic poem. The province was the home of the great hero Rustam, the warrior par excellence of the ancient Iranian tradition. It was this Rustam who slew his son Sohrab in ignorance in one of the most famous dramas of the entire corpus. As they have come down to us, the stories were composed by the poet Firdawsi in the early eleventh century. In fact, legends of Rustam were well known by the time of the coming of Islam, not just in Iran but also in the Arabian peninsula. We are told that they were recited in Mecca in the Prophet’s lifetime and are said to have distracted frivolous minds from his preaching. It is not clear what, if any, historical truth lay behind the legends, but the so-called stable of Rakhsh, Rustam’s celebrated horse, was still shown to travellers in the early Islamic period. At the time of the conquests, the province boasted a famous Zoroastrian fire at Karkūya. It survived the Muslim conquest and was still in use in the thirteenth century when it was said to have two domes dating ‘from the time of Rustam the Strong’. The fire, which was never allowed to go out, lay underneath the domes. It was served by a group of priests. The priest on duty sat well back from the flames with a veil over his mouth so as not to pollute them with his breath. He fuelled the fire with tamarisk logs, put on with silver tongs. We have no idea when the temple was destroyed but it may have been a victim of the chaos that engulfed the whole area at the time of Timur’s invasions at the end of the fourteenth century.

Sistan was also the home of a small Christian community. Out here, the east of the Sasanian Empire, the Christians were all Nestorian, that is to say that they belonged to the eastern Syrian Church, regarded as heretics by the Greek ‘Orthodox’ of Constantinople. It is typical that most of our information about this community comes down as a result of a dispute about the election of rival bishops in 544, when the patriarch at Ctesiphon had to broker a compromise that left one bishop at the capital Zaranj and another further east at Bust, now in southern Afghanistan. A Christian text composed in about 850 also records a monastery of St Stephen in Sistan, but the history and whereabouts of this establishment are otherwise completely unknown.

The Arab invasion of Sistan

30 was the logical continuation of Abd Allāh b. Āmir’s drive to the east in pursuit of Yazdgard III as he fled to escape the invaders. The route from Kirman to Sistan was always difficult, lying as it did across the corner of the great salt desert, the Dashti-Lut. The road is long and hard, and the first Muslim raid was wiped out, not by the heat, but by a fierce snowstorm. In 651-2 Abd Allāh sent an expedition into the province. As usual, many towns surrendered, content to make terms that would spare them war and destruction. The local capital, Zaranj, however, was a well-fortified city, with a powerful citadel which some said had been constructed by Alexander the Great. Here there was some fierce fighting before the Marzban agreed to make terms. He held a council of the local notables, including the

mobadh, a Zoroastrian religious leader, and they agreed to surrender to avoid further bloodshed. The terms were the payment of a million silver dirhams in tribute each year along with a thousand slave boys, each with a golden cup in his hand. After the capture of Zaranj, the invaders considered making an attack on Bust, the leading city of southern Afghanistan, but they encountered fierce resistance.

The last of the Sasanian kings, Yazdgard III, was still on the run, looking for a place of refuge where he could rally the fugitive remnants of his army.

31 The king was offered asylum in the mountainous principality of Tabaristān. This would probably have saved his life, but it would have been impossible to mobilize sufficient resources in Tabaristān to recover his kingdom. There is also a tradition that he appealed for support from the rulers of China. Instead he headed for Sistan, probably intending to reach Khurasan in the end. According to later tradition, he insisted on moving with a swollen and luxurious court, despite his straitened circumstances. He is said to have had 4,000 people with him: slaves, cooks, valets, grooms, secretaries, wives and other women, old people and children of the household - but not a single warrior. What made the situation worse for his reluctant hosts was that he also had no money to feed them: they would need to be generous as well as brave.

32 His appeals for assistance in Sistan fell on deaf ears: after all, he had only been king for a very short time and had no tradition of loyalty to rely on. The local lords seem to have preferred the idea of making their own peace with the invaders rather than pledging their loyalty to a king with a track record of failure.

From Sistan he moved on to Khurasan. It was here in the north-east corner of his empire, in a land he may never have visited before, that the endgame of the Sasanian Empire was played out. It was a miserable end to a great story; no heroic resistance against the odds here. The fugitive king seems to have been regarded as a liability, an unwanted guest rather than a hero, and the divisions that had undermined the Sasanian resistance to the Arab invasion continued to the very end. At Tus the local lord gave him gifts but also made it clear that the citadel was not big enough to contain his entourage; he would have to move on.

And so it was that Yazdgard came to the great frontier city of Merv. Merv had long been the eastern outpost of the empire against the Turks of the steppes. It was an enormous and very ancient city. At its heart was the old ark or citadel, a huge, roughly round construction of mud brick, with the vast sloping walls characteristic of Central Asia. It dated back to the Achaemenid times if not before. To this the Seleucids had added a vast rectangular enclosure which now contained the residential quarters of the city. It was also defended by a massive rampart, crowned by fired-brick interval towers. The tops of the defences had recently been strengthened by the addition of galleried walls with arrow slits. It could have held out against the Arab invaders indefinitely. Within the walls, the city was a maze of narrow streets and one-storey mud-brick houses. Traces of a Buddhist temple have been discovered and there must have been Zoroastrian fire-temples as well. We know there was a Christian community which was to play its role in the unfolding tragedy.

The reaction of the Marzban of Merv to the arrival of his fugitive sovereign was to try to get rid of him as soon as possible. He made an alliance with the neighbouring Turkish chief, the ancient enemy, against Yazdgard. The monarch got to hear that troops were being sent to arrest him and left the city secretly at night. The exhausted king eventually took refuge in a watermill on the Murghāb river, which watered the Merv oasis, and it was here that the last of the Sasanians was done to death. What exactly happened that night can never be known,

33 but the great Iranian epic, the

Shahnāmah, suggests what transpired, and the poet Firdawsi uses it to conclude his great epic of Persian kingship.

34According to the Shahnāmah, after the defeat and death of Rustam at Qādisiya, Yazdgard consulted the Persians. His adviser, Farrukhzād, suggested that he should flee to the forests of Narvan, at the south end of the Caspian Sea, and prepare a guerrilla resistance, but the king was not convinced. The next day he sat on his throne, put his crown on his head and asked advice from the nobility and the priests. They were not in favour of the plan and the king agreed: ‘Am I to save my own head and abandon Persia’s nobility, its mighty armies, the land itself, and its throne and crown? ... In the same way that the king’s subjects owe him allegiance in good times and in bad, so the world’s king must not abandon them to their sufferings while he flees to safety and luxury.’

The king then proposed that they go to Khurasan: ‘We have many champions there ready to fight for us. There are noblemen and Turks in the Chinese emperor’s service, and they will side with us.’ Furthermore Mahuy, the lord of the marches there, had been a humble shepherd until Yazdgard had raised him to fortune and power. Farrukhzād, the wise counsellor, was not convinced, arguing that he should not trust men ‘with a lowly nature’, a typical example of the aristocratic mind-set of the Sasanian nobility. The king set out for Khurasan, accompanied by the lamentations of Persians and Chinese alike. They went stage by stage to Rayy, where ‘they rested for a while, consoling themselves with wine and music’, before pressing on ‘like the wind’.

As they approached Merv, the king wrote to the governor, Mahuy, who came out to meet him with a great show of loyalty. At this point the faithful Farrukhzād handed over responsibility for his monarch to Mahuy and left for Rayy, full of gloomy presentiments and lamenting Rustam, ‘the best knight in all the world’, who had been killed by ‘one of those crows in their black turbans’. Mahuy’s thoughts turned to treachery. He wrote to Tarkhūn, ruler of Samarqand, and suggested a joint plot against Yazdgard. Tarkhūn agreed to send his Turkish forces against Merv. When Yazdgard was warned of their approach, he put on his armour and prepared to confront them. He soon realized, however, than none of his men was following him, that Mahuy had withdrawn from the fight and the king was left on his own. He fought furiously but was soon forced to flee, abandoning his horse with its golden saddle, his mace and his sword in its golden sheath. He took refuge in a watermill on one of the rivers of Merv.

At this low point in the king’s fortunes, the poet reflects, with that world-weary pessimism that was to characterize the work of later Persian poets like Umar Khayyām, on the harshness of fate.

This is the way of the deceitful world, raising a man up and casting him down. When fortune was with him, his throne was in the heavens, and now a mill was his lot; the world’s favours are many, but they are exceeded by its poison. Why should you bind your heart to this world, where the drums which signal your departure are heard continuously, together with the caravan leader’s cry of ‘Prepare to leave’? The only rest you find is that of the grave. So the king sat, without food, his eyes filled with tears, until the sun rose.

The miller opened the mill door, carrying a load of straw on his back. He was a humble man called Khusraw, who possessed neither a throne, nor wealth, nor a crown, nor any power. The mill was his only source of living. He saw a warrior like a tall cypress seated on the stony ground as a man sits in despair; a royal crown was on his head and his clothes were made of glittering Chinese brocade. Khusraw stared at him in astonishment and murmured the name of God. He said, ‘Your majesty, your face shines like the sun: tell me, how did you come to be in this mill? How can a mill full of wheat and dust and straw be a place for you to sit? What kind of man are you with this stature and face of yours, and radiating such glory, because the heavens have never seen your like?

The king replied, ‘I’m one of the Persians who fled from the army of Turan [the Turks]’. The miller said in his confusion, ‘I have never known anything but poverty, but if you could eat some barley bread, and some of the common herbs which grow on the river bank, I’ll bring them to you, and anything else I can find. A poor man is always aware of how little he has.’ In the three days that had passed since the battle the king had had no food. He said, ‘Bring whatever you have and a sacred barsom’,

f The man quickly brought a basket of barley bread and herbs and then hurried off to find a barsom at the river toll-house. There he met up with the headman of Zarq and asked him for a barsom. Mahuy had sent people everywhere searching for the king, and the headman said, ‘Now, my man, who is it who wants a barsom?’ Khusraw answered him, ‘There’s a warrior on the straw in my mill; he’s as tall as a cypress tree, and his face is as glorious as the sun. His eyebrows are like a bow, his sad eyes like narcissi: his mouth is filled with sighs, his forehead with frowns. It’s he who wants the barsom to pray.’ The headman duly sent the miller on to Mahuy, who ordered him to return to his mill and kill the king, threatening that he himself would be executed if he did not, and adding that the crown, earrings, loyal ring and clothes should not be stained. The reluctant miller returned and did as he was told, stabbing the king with a dagger. Mahuy’s henchmen soon appeared and, stripping off the insignia of royalty, threw the body into the river.

In a curious coda to the story, the poet describes how the Christian monks from a neighbouring monastery saw the corpse, stripped off their habits and pulled it out of the water. They made a tower of silence for him in a garden. They dried the dagger wound and treated the body with unguents, pitch, camphor and musk; then they dressed it in yellow brocade, laid it on muslin and placed a blue pall over it. Finally a priest anointed the king’s resting place with wine, musk, camphor and rosewater.

Mahuy, of course, was furious, saying that Christians had never been friends of Iran and that all connected with the funeral rights should be killed. He himself soon came to a bad end. Macbeth-like, he regretted his regicidal actions: ‘No wise man calls me king and my seal’s authority is not respected by the army ... Why did I shed the blood of the king of the world? I spend my nights tormented by anxiety, and God knows the state in which I live.’ His Malcolm soon arrives, in the guise of the leader of the troops of Tarkhūn of Samarqand. The treacherous Mahuy and his sons are taken and, after their hands and feet are cut off, they are burned alive.

‘After that’, the poet laconically concludes, ‘came the era of Umar, and, when he brought the new faith [Islam], the pulpit replaced the throne.’

The death of Yazdgard III was followed by the Arab occupation of Merv, which seems to have been accomplished peacefully, but the details are entirely lacking.

The fall of Merv and the death of the last Sasanian marked the end of the first phase of the Muslim conquest of Iran. Virtually the whole of what is now the territory of modern Iran, along with some areas in the Caucasus and Turkmenistan, had now acknowledged Muslim overlordship in one form or another. The fall of the great Sasanian Empire had been swift and decisive. Despite the great reputation of the ancient monarchy, attempts to revive it were few and ineffectual. The old political order had gone for good, but much of Iranian culture survived the conquests. The Arabs had defeated the Sasanian armies. They had secured tribute from most of the major cities and had control of most, but by no means all, of the great routes, but that was about it. The only major Muslim garrison seems to have been at Merv, on the north-eastern frontier, and even here the troops were sent on rotation from Iraq for some years, rather than being permanently settled. For the first half-century of Muslim rule, there was no extensive Muslim presence, no Muslim new towns were founded, no great mosques built. ‘Conquest’ was often a form of cooperation with local Iranian elites, as was the case at Qumm and Rayy. Many areas, such as the mountain principalities of northern Iran, were entirely outside Muslim control, and the direct road from Rayy to Merv remained unusable because of the threat they posed.

The fall of Merv may have marked the end of the campaign against the Sasanians and the establishment of Muslim hegemony in what is now Iran, but there was much more fighting before Arab rule became a reality in many areas of the country. Throughout the late seventh and first decades of the eighth century, Arab armies were pushing into unknown territory on the fringes of the Iranian world.

An interesting example of these secondary conquests can be seen in the case of Gurgān and Tabaristān. The story is a complex one but does illustrate how many different factors could be involved in the Muslim conquest of an area, and above all the interplay between existing political powers and the Arab incomers. Tabaristān was the mountainous region on the southern shore of the Caspian Sea, Gurgān the lower area to the east where the heights of the Iranian plateau gave way to the steppe land and deserts of Central Asia. At the time of the initial conquests, the rulers of these areas, the Sūl of Gurgān and the Ispahbādh of Tabaristān, had entered into treaty arrangements with Arab commanders which effectively allowed them to remain in control of their own domains. By the beginning of the eighth century, as Muslim rule in the rest of Iran strengthened, this position began to look increasing anomalous. They posed a clear threat to communications between the Arab base in Merv and the west, and it was not until after 705 that the Arabs were able to use the direct road from Rayy to Merv, rather than the much longer southern route through Kirman and Sistan.

35 Local resistance was also weakened by the tensions between the Turks of Dihistān on the desert margins, led by the Sūl, and the settled inhabitants of Gurgān.

In 717 Yazīd b. al-Muhallab, the newly appointed governor of Khurasan, decided to launch a major military expedition in these areas. Yazīd’s predecessor as governor, Qutayba b. Muslim, had achieved great fame for his conquests in Transoxania, and there is no doubt that Yazīd wanted to emulate him and show that he could lead armies against the unbelievers and reward them with abundant booty. He is said to have gathered 100,000 men from Khurasan, and the Iraqi military towns of Kūfa and Basra.

36 The first objective seems to have been the town of Dihistān, an isolated outpost of settlement in the deserts of Turkmenistan. He blockaded the city, preventing the arrival of food supplies, and the Turks, who formed the bulk of the defenders, began to lose heart. The

dehqān in command wrote to Yazīd asking for terms. He asked only for safety for himself and his household and animals. Yazīd accepted, entered the city and took booty and captives; 14,000 defenceless Turks, who were not included in the amnesty, were put to the sword.

37In another version of the story, the Sūl of Dihistān retired to his fortified stronghold on an island at the south-east corner of the Caspian. After a siege of six months, the defenders became ill with the bad drinking water and the Sūl opened negotiations and agreed terms. As usual, there are admiring descriptions of the booty, including sacks of food and clothes. Yazīd himself acquired a crown and immediately passed it on to one of his subordinates. Crowns were frequently worn by members of the Iranian aristocracy but were regarded with deep suspicion by the more pious and austere Muslims, who considered them typical of the pomp and vanity of the Persians. Perhaps because of this, the subordinate protested that he did not want it, and the officer gave it to a beggar. Yazīd heard about this and purchased the crown back from the mendicant.

After the defeat of the Sūl, Yazīd was able to occupy much of the settled land of Gurgān without major resistance, especially as some at least of the local Iranian population were happy to accept Arab support to protect them from the Turks. Yazīd then turned his attention to mountainous Tabaristān. The local ruler, the Ispahbādh, had summoned allies from the mountainous provinces of Gīlān and Daylam further to the west.

The people of Tabaristān had defeated earlier Muslim attempts to penetrate the narrow passes of their native mountains

38 and were determined to do so again. When the two armies met on the plains, the Muslims had the advantage, but as soon as they retreated to the mountains, the local people were able to make good use of the terrain to defend themselves: ‘as soon as the Muslims began their ascent, the enemy soldiers, who were looking down on them, opened fire with arrows and stones. The Muslim soldiers fled without suffering great losses because the enemy was not strong enough to pursue them, but the Muslims crowded and jostled each other so that many of them fell into ravines.’

39 This success emboldened the local people, there was an uprising against the small number of Arabs left as a garrison in Gurgān

40 and for a time Yazīd’s army was in serious danger of being trapped and destroyed. Only some clever diplomacy allowed him to make a peace deal, which could be portrayed as a success. In addition to some fairly large sums of money, the Ispahbādh of Tabaristān agreed to pay 400 donkeys loaded with saffron and four hundred slaves. Each slave was to be dressed in a cloak with a scarf on it, carrying a silver cup and a piece of fine white silk.

The silk and the silver cups could not disguise the fact that the massive campaign had ended in partial failure. The lowlands of Gurgān were brought under Muslim rule, but the people of Tab-aristān, protected by their mountains, had fought off the challenge. According to a local history of the area, written several centuries after the events but still preserving old traditions, Yazīd set about urbanizing Gurgān, which until then had not been a real city at all. He is said to have built twenty-four small mosques, one for each Arab tribe, most of which could still be identified in the author’s own day.

41 This marks the real beginning of Muslim rule in Gurgān, seventy years after the initial Arab conquest. Even then the Islamic community seems to have been confined to the newly established capital; it would take much longer for the new religion to penetrate the villages and nomad encampments.

42The most determined resistance the Arabs faced in the lands of the Sasanian Empire came from the area of eastern Sistan, the Helmand and Kandahār provinces of modern Afghanistan. The campaigns in this area are also interesting because the harshness of the fighting provoked the only full-scale mutiny recorded among Arab troops at this time. The desert areas of southern Afghanistan are a difficult environment for any invading army. The scorching heat is very debilitating and the rugged hills provide endless points of shelter and refuge for defenders who know the area well. This was neither Zoroastrian nor Buddhist territory but the land of the god Zun, whose golden image with ruby eyes was the object of veneration throughout the area. The kings of this land were called Zunbīls, their title proclaiming their allegiance to the god, and they moved between their winter palaces on the plains by the Helmand river and their summer residences in Zābulistān, the cooler mountains to the north.

A Muslim force had raided the area as early as 653-4, when the Arab commander had allegedly poured scorn on the image of the god, breaking off one of his arms and taking out his ruby eyes. He returned them to the local governor, saying that he had wished to show only that the idol had no power for good or evil. The god, howoever, survived this insult and was still being venerated in the eleventh century, symbolizing the fierce resistance of the people of these barren hills to outside interference. The early Muslims were well aware that this area was a potential route to India, with all its riches, but the Zunbīls and their relatives, the Kabulshāhs of Kabul and their peoples, mounted a spirited and long-lasting resistance to the Arabs, making it impossible for Muslim armies to reach northern India.

It was into this fiercely hostile environment that Ubayd Allāh b. Abī Bakra led the ‘Army of Destruction’ in 698.

43 Ubayd Allāh himself was a typical example of a man of humble origins who had done very well out of the Muslim conquest. His father was an Ethiopian slave in the city of Tā’if near Mecca. When the Muslims were besieging the town in 630, two years before the Prophet’s death, he had proclaimed that any slave who came over to his side would be free. Abī Bakra had used a pulley to lower himself over the town walls and so acquired his nickname, the Father of the Pulley. He married a free Arab woman and their son, Ubayd Allāh, inherited his dark skin colour. His slave origins were exploited by satirists. The family moved to Basra when the town was founded and made large sums of money out of urban development by building public baths. Ubayd Allāh was able to build himself a very expensive house and to keep a herd of 800 water buffalo on his estates in the marshlands of southern Iraq. The conquest of Fars provided new opportunities for making money, and we have already seen him making vast sums from the confiscation of the assets of the fire-temples there. He was, in short, a man of obscure origins and little military experience who made a fortune out of the conquests.

Hajjāj b. Yūsuf, governor of Iraq and all the east, now appointed him to command a Muslim army against the Zunbīl, who was refusing to pay tribute, ordering him to go on attacking until he had laid waste the land, destroyed the Zunbīl’s strongholds and enslaved his children. The army was assembled at the Muslim advanced base at Bust. They then marched north and east in pursuit of the Zunbīl. Their enemies withdrew before them, luring them further and further into the rugged mountains. They removed or destroyed all the food supplies and the heat was scorching. Ubayd Allāh soon found himself in a very perilous position and began to negotiate. The would-be conqueror was forced to offer a large sum of tribute, to give hostages including three of his own sons and to take a solemn oath not to invade the Zunbīl’s land again. Ubayd Allāh was lavishly entertained by the monarch with women and wine.

44 Not all the Muslims were happy to accept this humiliation and some determined to fight and achieve martyrdom, arguing that Muslims should never be prevented from attacking infidels, and, much more practically, that Hajjāj would deduct the tribute from their salaries, leaving them without any rewards for the hardships they had endured during the campaign.

A few brave souls elected to fight and achieved the martyrdom they wished. Most followed their commander in a desperate retreat to Bust. Only a small number made it, the rest perishing from hunger and thirst. Of the 20,000 men ‘with their mailed horses and panoply of weapons’ who had set out, only 5,000 returned. It was widely believed that Ubayd Allāh himself was exploiting the situation by commandeering any grain and selling it on to his troops at vastly inflated prices. As the ragged remnants of the army approached Bust they were met by a relieving force bringing some supplies, but many of the starving wretches ate so fast that they perished and the survivors had to be fed slowly with small quantities. Ubayd Allāh himself reached safety but died very soon after. The poets were merciless in their criticism of his incompetence and, above all, of his greed and the way he had exploited his troops to make money.

You were appointed as their Amir

Yet you destroyed them while the war was still raging

You stayed with them, like a father, so they said

Yet you were breaking them with your folly

You are selling a

qafizg of grain for a whole dirham

While we wondered who was to blame

You were keeping back their rations of milk and barley

And selling them unripe grapes.

45

It was probably the most significant setback for Muslim arms since the Arab conquests had begun. Hajjāj in Iraq was determined to seek revenge and seems to have been genuinely afraid that the Zunbīl would attack areas already under Muslim rule: if he was joined by an uprising of local people all of Iran might be lost. He wrote to the caliph Abd al-Malik in Damascus, explaining that ‘the troops of the Commander of the Faithful in Sistan have met disaster, and only a few of them have escaped. The enemy has been emboldened by this success against the people of Islam and has entered their lands and captured all their fortresses and castles’.

46 He went on to say that he wanted to send out a great army from Kūfa and Basra and asked the caliph’s advice. The reply gave him carte blanche to do as he saw fit.

Hajjāj set about organizing the army, 20,000 men from Kūfa and 20,000 from Basra. He paid them their salaries in full so that they could equip themselves with horses and arms. He reviewed the army in person, giving more money to those who were renowned for their courage. Markets were set up around the camp so that the men could buy supplies and a sermon encouraging everybody to do their bit for the jihād was preached.

47 The expeditionary force became known as the ‘Peacock Army’ because of the elegance of its appearance.

Despite these preparations, the expedition set in train the only military mutiny in the history of the early conquests, the only time an Arab army refused to go on fighting and turned on its Muslim political masters. All was not as straightforward as it looked. Hajjāj had been struggling for some years to force the militias of the Iraqi towns to obey him and the caliph in Damascus. Sending them on a long, hard campaign could be very advantageous: if they were successful they might become rich and satisfied and even settle in the area. If they were not, then their power would be broken. As commander, he chose one Ibn al-Ashcath. Unlike the unfortunate Ubayd Allāh, Ibn al-Ashcath came from the highest ranks of the south Arabian aristocracy, being directly descended from the pre-Islamic kings of Kinda. He was also a proud man who did not like being ordered about, and had become one of the leaders of the Iraqi opposition to Hajjāj. Putting him in charge was really offering him a poisoned chalice.

At first all went well. The Zunbīl, who seems to have been very well informed about the Muslim preparations, wrote to Ibn al-Ash

cath offering peace. He was given no reply and the Muslim forces began a systematic occupation of his lands, taking it over district by district, appointing tax collectors, sentry posts to guard the passes and setting up a military postal service. Then, sensibly, Ibn al-Ash

cath decided to pause and consolidate, before advancing the next year. He wrote to Hajjāj about this perfectly reasonable course of action and received a massive blast in return. Hajjāj accused the commander of weakness and confused judgement and of not being prepared to avenge those Muslims who had been killed in the campaign. He was to continue to advance immediately. Ibn al-Ash

cath then called for advice. Everyone agreed that Hajjāj’s demands were unreasonable and designed to humiliate the army and its leader. ‘He does not care’, one said, ‘about risking your lives by forcing you into a land of sheer cliffs and narrow passes. If you win and acquire booty he will devour the territory and take its wealth ... if you lose, he will treat you with contempt and your distress will be no concern of his.’

48 The next speaker said that Hajjāj was trying to get them out of Iraq and force them to settle in this desolate region. All agreed that the army should disavow its obedience to Hajjāj. Ibn al-Ash

cath then decided to lead them west to challenge Umayyad control of Iraq and the wider caliphate, leaving the Zunbīl in control of his territory and the Muslim dead unavenged.

The mutiny was not a success. Ibn al-Ashcath and his Iraqi followers were defeated by the Syrian Umayyad army and crushed. But the story is important in the annals of the conquests: a Muslim army had decided that asserting its rights against the Muslim government was more important than expanding the lands of Islam and that preserving their salaries was more valuable than the acquisition of new booty. We can see the conquest movement beginning to run out of steam.

The failure of Muslim arms in southern Afghanistan marked the end of the conquests in Iran. Only to the north-east, across the River Oxus, did wars of conquest continue. The partial and scattered nature of the Muslim conquest of Iran had an important cultural legacy. In Syria, Iraq and Egypt, the Muslim conquests also led to the triumph of the Arabic language, both as the medium of high culture and the vernacular of everyday life. This did not happen in Iran. For two centuries after the conquest, and longer in some areas, Arabic was the language of imperial administration. It was also the language of religious and philosophical discourse. But it was not the language of everyday life. When independent Iranian dynasties asserted their independence from the rule of the caliphs in the ninth and tenth centuries, the language of their courts was Persian. This ‘New Persian’ was written in Arabic script and contained numerous Arabic loan-words, but the grammar and the basic vocabulary were clearly Persian, an Indo-European language in contrast to the Semitic Arabic. It is worth considering how different this is to the position in Egypt. In Egypt in the year 600 nobody spoke Arabic; by the twelfth century at the latest, everybody spoke Arabic and in modern times Egypt is thought of as a prime centre of Arabic culture. In Iran in 600 nobody spoke Arabic; by the twelfth century they still did not. Arabic was established as the language of certain sorts of intellectual discourse, very much like Latin in medieval Europe. In modern times Iran is emphatically not an Arab country.

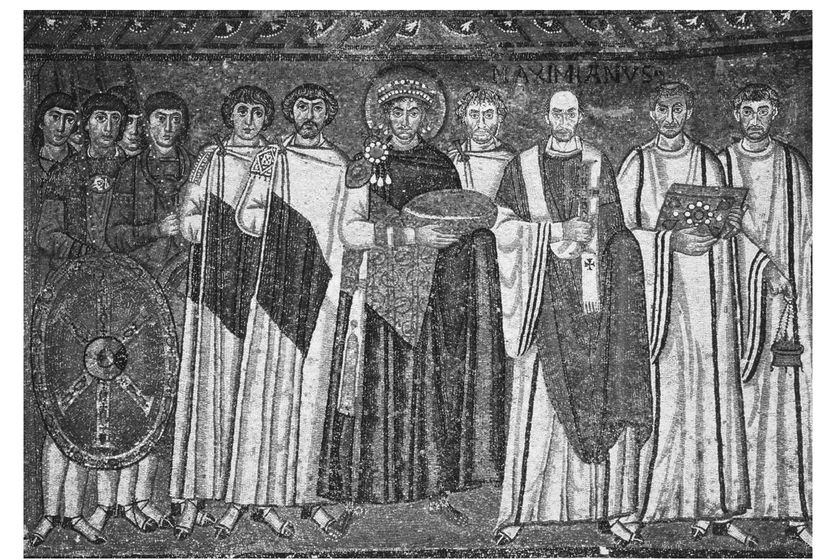

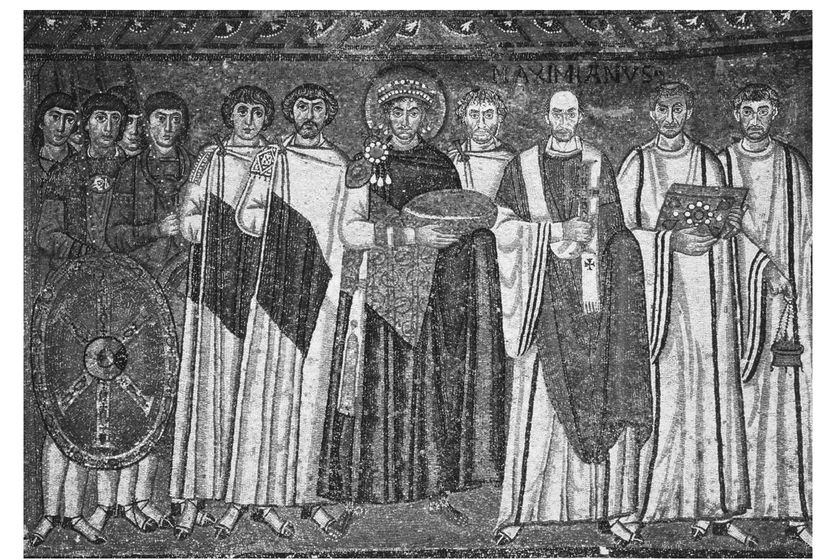

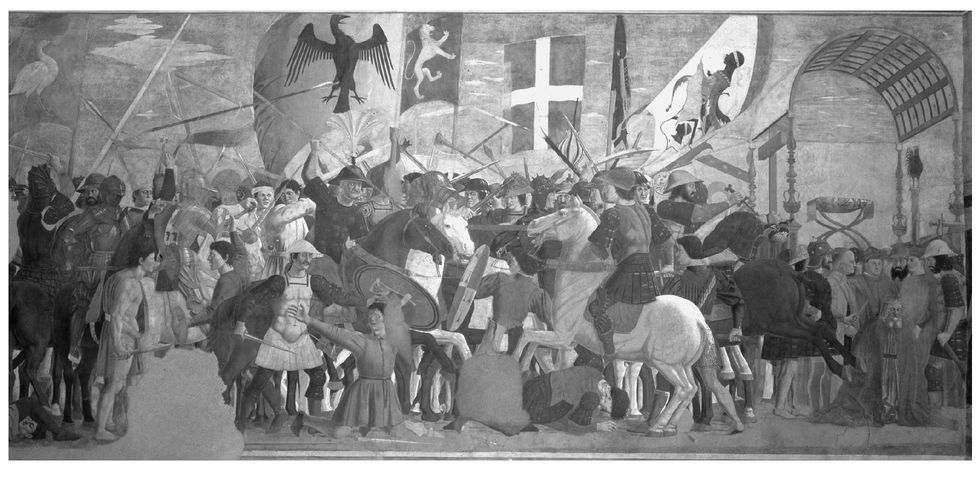

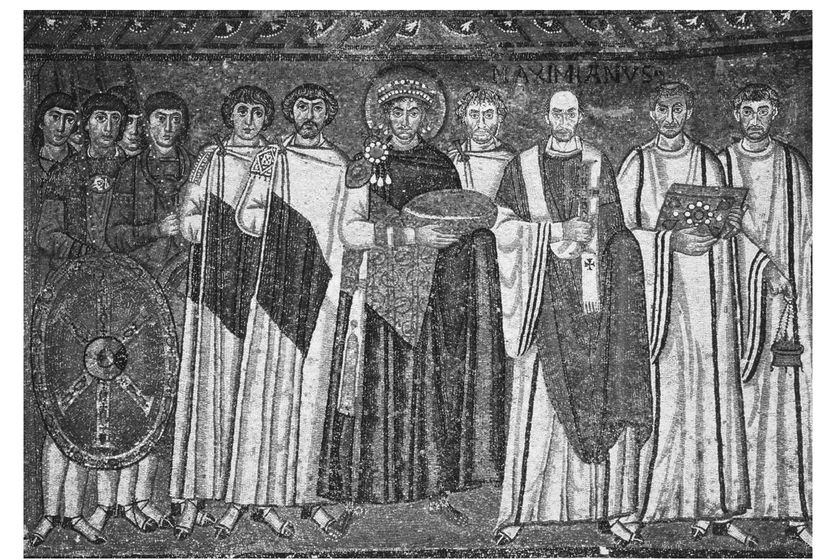

This mosaic of Emperor Justinian I (527-65) and his court from San Vitale, Ravenna, shows Byzantine imperial style. Stately, almost motionless, the Emperor is in civilian clothes and surrounded by his retinue of officials, soldiers and clergy. (© San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library)

The last Sasanian shāh Yazdgard III (632-51) is depicted on this silver gilt plate. In contrast to Justinian, he is depicted as a mighty hunter and warrior pursuing his prey on a galloping horse. (Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, France/Flammarion/The Bridgeman Art Library)

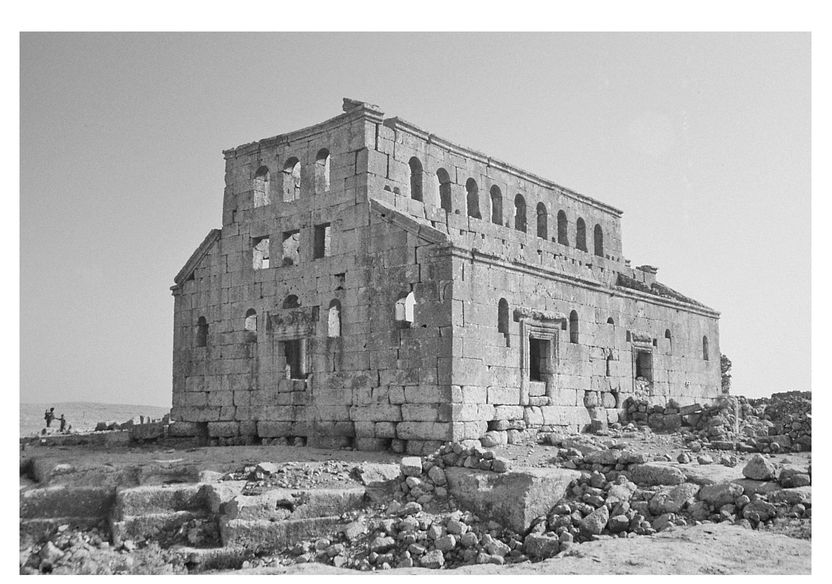

TOP Mushabbak Church (Syria). The sixth-century basilical church in northern Syria is typical of the hundreds built for congregational worship in what was a profoundly Christian country before the Muslim conquest. (Author)

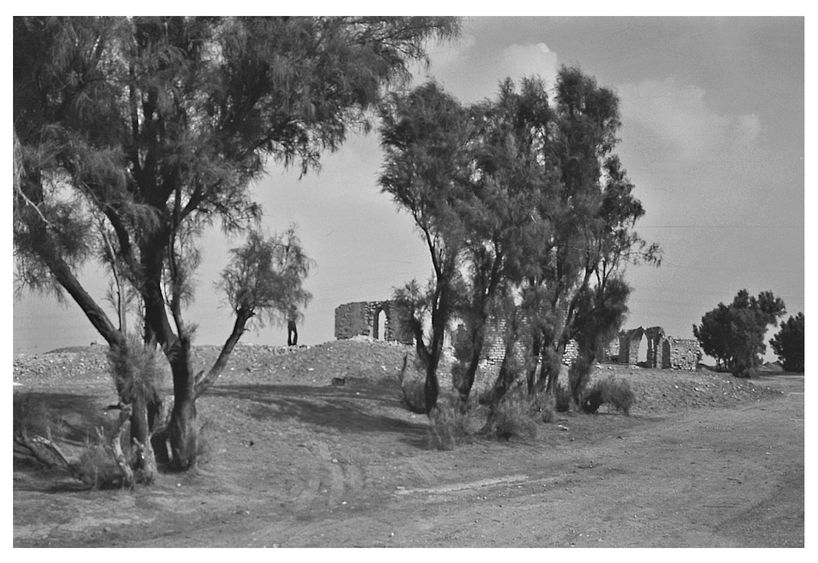

ABOVE Fire-temple Konur Siyah (Fars, Iran). Zoroastrian fire-temples like this one were constructed to shelter the sacred fire under the main dome and to accommodate the priests who tended the fire. Zoroastrianism was the official religion of the Sasanian Empire. (Author)

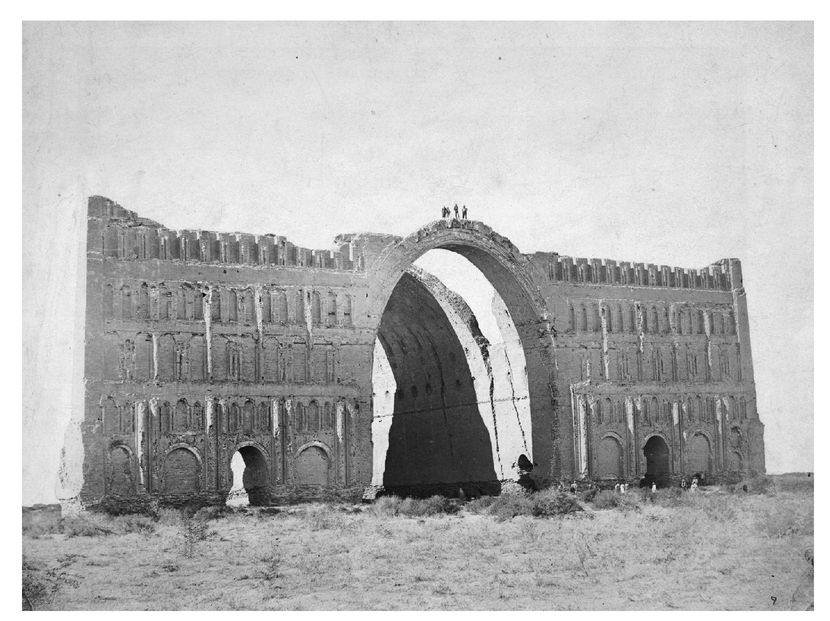

TOP Taqi-kisrā (Iraq); photograph taken in 1901, after the collapse of much of the palace in the 1880s. The iwãn (arch) of the great palace at Ctesiphon, capital of the Sasanian Empire, was probably built by the last great Sasanian shāh, Chosroes II (d. 628). The victorious Muslims used it as their first mosque and prayed surrounded by the statues of former Persian monarchs. (Royal Geographical Society/The Bridgeman Art Library)

ABOVE The ruin of the Marib dam, Yemen. The final collapse of the dam in the late sixth century was symbolic of the decay of the old kingdom of Himyar, which had dominated Yemen in the centuries before the coming of Islam. (Author)

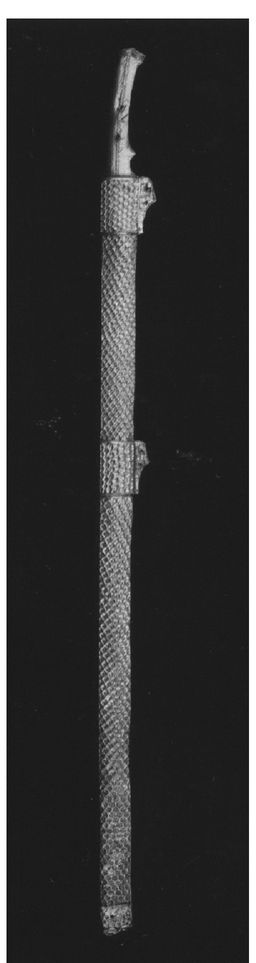

This seventh-century Sasanian helmet shows the rich military equipment typical of the Persian army. Arab writers like to contrast the ostentation of the Persians with their own simple arms. (Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, Mainz. Inv. O.38823.)

This richly decorated Sasanian sword would have been worn by the aristocrats who led the Persian armies. (British Museum, London. Inv. BM 135738)

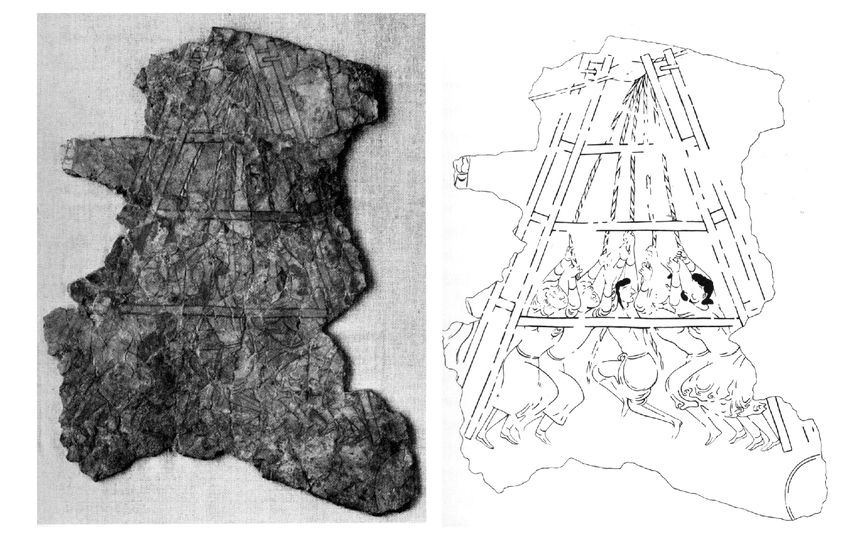

David confronts Goliath, from the ‘David Plates’. These Byzantine silver plates illustrate the triumph of David over Goliath and depict the arms and armour of Byzantine troops in about 600, a metal breastplate with protective strips or scales covering his arms and skirt. (The Metropolita Museum of Art, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.396) Photograph © 2000)

Modern sketch of an early eighth-century wall-painting, depicting a swing-beam siege engine in operation, probably being used by Muslims attacking Samarqand. The Arab conquests in Transoxania witnessed a series of hard-fought sieges. (Tile fragment from the Hermitage, St Petersburg Drawing by Guitty Azarpay, in Sogdian Painting, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981, p. 65)

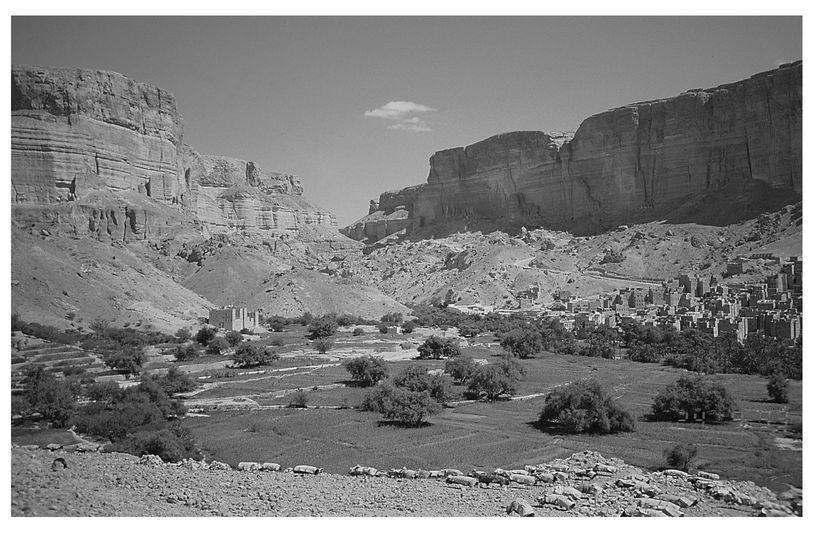

TOP Wadi Ducān. Not all the early Arab conquerors were tent-dwelling nomads. Many were village people from settlements like this one in Yemen. They played a major but often forgotten role in the conquests of Iraq and Egypt. (Author)

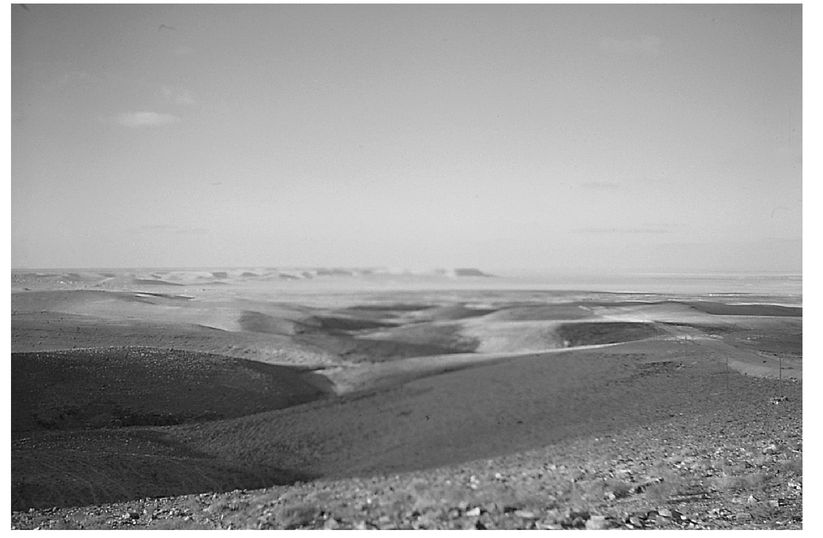

ABOVE Syrian desert. For the Bedouin Arabs the desert was a place of opportunity, danger and beauty, a wild homeland celebrated in poetry and legend. (Author)

TOP Ancient Roman walls of Damascus. The city is still largely surrounded by the Roman walls to which the Muslims laid siege in c. 636. (Author)

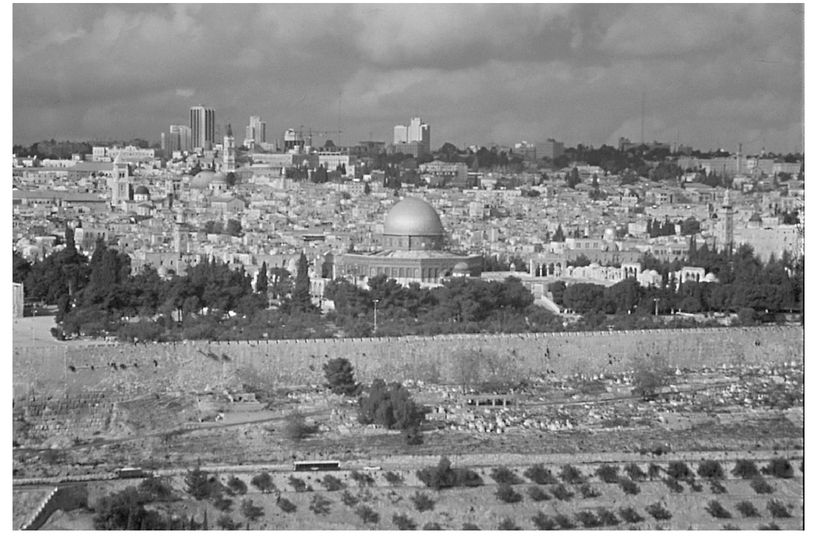

ABOVE Jerusalem seen from the Mount of Olives. The temple platform, where the Dome of the Rock now stands, seems to have been a waste land at the time of the Muslim conquests. Here the caliph Umar is said to have constructed a simple place of worship. (Author)

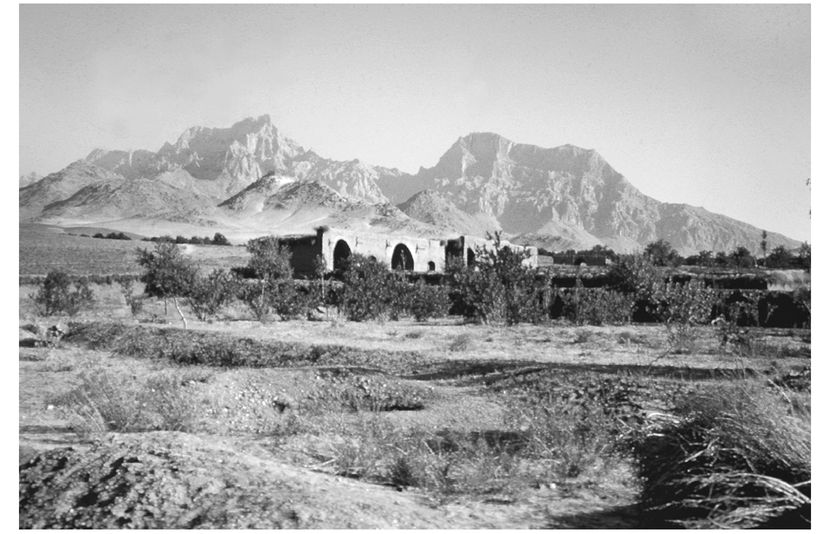

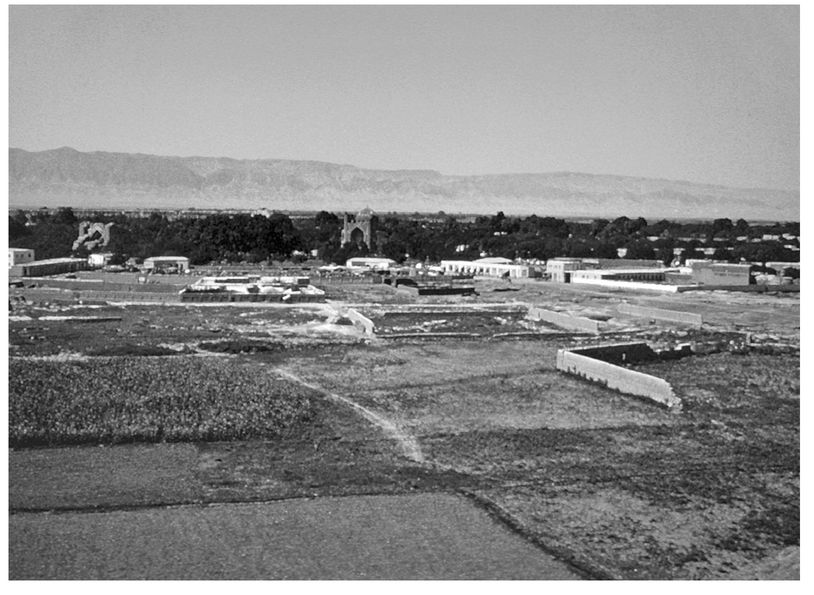

TOP The Zagros Mountains separate the flat plains of Iraq from the Iranian plateau. After the conquest of Iraq, the Muslim leaders decided to push on through this rugged terrain where they defeated the Persian armies once more at Nihāvand (641). (Author)

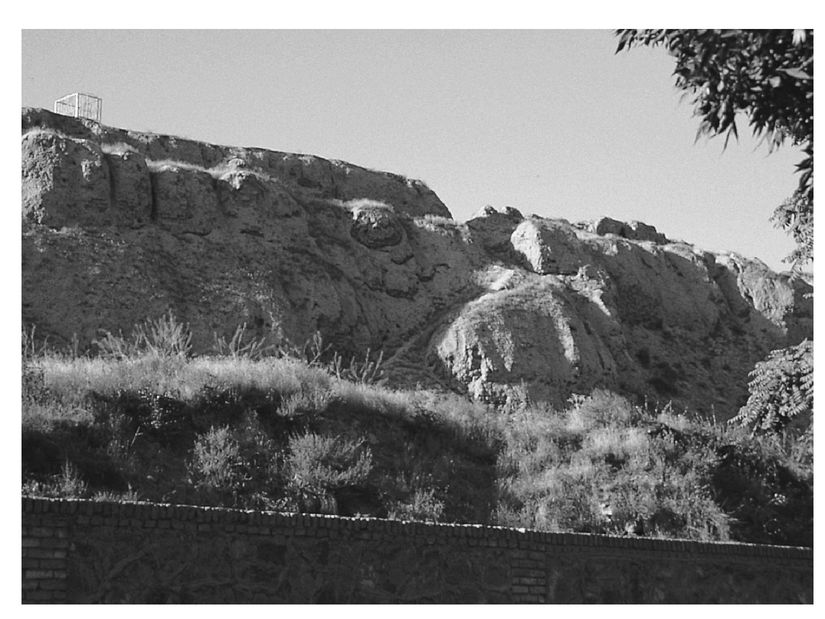

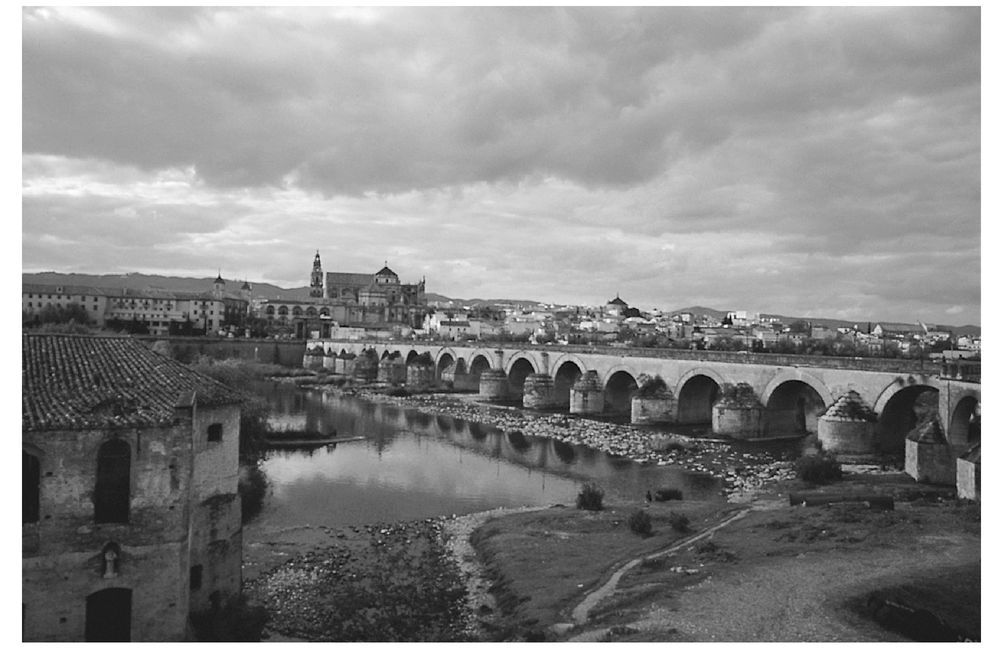

ABOVE Walls of Bishapur. The Sasanian fortifications of this town in Fars, with their stone walls and regularly spaced round towers, could not survive Muslim attack after the main Persian Imperial army had been defeated. The ruins of the citadel can be seen on the hills in the background. (Author)