The Flood

Charles Koschade rolled to a standstill. A car was on its roof by the road. One window had cracked; another shattered. The overturned Camry was empty—no broken body inside— yet the vehicle’s blinker was flashing and its headlights were switched on. Just starting to fade as the battery drained of power. A tyre turned, dripping rainwater. Charles lifted his foot off the brake when the truck in front of him moved, inching forward with the incline of the road, engine idling. A crackle of broken glass below him as he rolled past the crashed vehicle at the intersection of Punt and Domain.

An ambulance had recently come and gone. A body would have been pulled out of the Camry, carried away, conscious or unconscious. Inside the vehicle were the spilled contents of a handbag: hairbrush, balled-up used tissues, cosmetics bag and box of tampons. There was a scattering of paper in and around the car. Pages and pages of drawings and sketches. They might have belonged to the driver of the Camry, or to her child.

A teenager stood on the top landing of an external staircase overlooking the intersection. The door of her apartment was open. She was wearing a dirty-white dressing gown and smoking a cigarette; talking on her phone as she used it to take a video of the scene below. Two pedestrians with dogs tugging on their leashes stood nearby. A woman wearing an oversized Driza-Bone talked to a man in a leaf-green puffer jacket. The early morning air from their mouths rose in puffs of fleeting steam. They were neighbours chatting about the crash or strangers who had stopped to share known details and to speculate.

A policewoman dismounted from a police motorcycle to direct drivers past the vehicle. When he first started driving Charles hadn’t really understood that police had to be at the scene, not so much to stop people colliding into each other or a crashed car (not a risk in this case, with the Camry on the footpath and sidelong against an ivy-covered wall) but simply to keep traffic flowing. Passers-by would stop if they weren’t impelled forward by police.

Drivers slowed so they might savour the disaster. Opened their eyes a touch wider to take in a catastrophe— still a little groggy from sleep. Lingering nightmares seen in the wide-awake world. Was it a kid that died here? Was it an artist? It might have been both, mother and child. A broken neck? A crushed skull? Was there another car that sped away after the accident? It would have left tyre marks on the road. How else might a car end up on its roof?

Pleasant thoughts because the bodies had been removed. There wasn’t any blood. So the guilt was distant, as was the loss of life. A terrible thing might have happened to those driving by if only they’d been further along the road. The pleasure was in coming close to tragedy—knowing that it would slip past now without touching anyone else.

He wasn’t more than a minute or two late for his pickup despite the accident. It turned out to be a short fare, barely worth the drive, taking an athlete to his dentist. He had an intense physicality, sitting in the passenger seat next to Koschade rather than in the back. He was dressed in UFC Reebok gear as though he was planning on going straight to a mixed martial arts gym afterwards yet asked Charles to return for him at 11:00 a.m. A general anaesthetic and the removal of four wisdom teeth meant the athlete had been advised not to drive afterwards. Koschade wanted to suggest the man could walk home; knew it wouldn’t be welcome advice.

“A taxi will be waiting for you after the surgery,” he told him instead.

Charles found nothing new when he woke his phone. He checked both his email and text messages, was about to read the thread once more when he noticed the athlete hadn’t disappeared after paying.

“But it won’t be you?” his passenger asked, standing in the open door.

Koschade was surprised at the question. Switched the screen to sleep and plugged the phone in to charge. After saying good morning to each other they had not talked. No conversational back and forth. The fighter had only explained about the wisdom teeth when asking to book a ride home.

“It doesn’t matter who picks you up,” he said.

The passenger didn’t respond. Koschade wasn’t sure whether the MMA athlete was leaning towards a thankyou or wanted to get back into the taxi to loosen his driver’s teeth with a straight punch.

“There will be a taxi waiting at 11:00 a.m.,” Charles reassured him.

Adrenaline kicked his heart into another gear and he found himself ready to brawl in the street. He couldn’t win against an octagon-ready fighter yet it wasn’t likely to get to that. Stopped traffic would flash lights and blare horns. Koschade had found that a real fight only ever happened if there was an encouraging audience. Posturing was usually enough, perhaps with some pushing.

His passenger held the door open for another moment, closed it with a hard push. A comfortable taxi silence was hard to find for some. Or it was simply pleasing to see the same face again rather than another total stranger. Koschade’s heart returned to a rest rate and he thought it had probably been too long since he’d had a fistfight for him to know how he would manage one these days. Maybe all he was good for now was posturing.

He drove without a destination, Maria Callas singing on random from his phone. Charles coasted along, heading towards the city through a residential area. He’d hit a major road soon. He had no idea what Callas was singing about. Even the titles of the songs meant nothing to him. Her voice was as much a nonsense to Charles as a songbird’s call, singing out from the woods. No matter how beautiful, such songs never made him want to enter the forest she’d lived in. He switched to ‘Wolf Like Me’, a track with maniacal drums and distorted guitars that was too raucous to play when he had a passenger.

Charles stopped when he saw a cafe and sat down at a table by the broad window inside to drink from porcelain. He found that paper or styrofoam ruined the flavour of coffee. He had a couple of emails from friends he didn’t want to read. A text from his father, but he didn’t want to look at that either. He put his phone back into his pocket.

Across the street he saw a collection of what had once been fine wood furniture arranged on a stretch of grass. Months had passed since the lawn was mowed. It sparkled a wet emerald in passing shafts of sunlight. The lush grass made the furniture look all the more striking. Dumped and then shifted into regular domestic configurations of bedroom, kitchen, dining room and lounge. An old armchair with a small red cushion. A bed, now in pieces, with a filthy mattress and ripped-open pillows. Damp feathers moved in the breeze as though some bird was stirring awake. Or settling to sleep. Beside the bed were two large lampshades with cracked spines. Drenched rugs dripped dirt from decades of use, worn thin and draped over the branches of a withered pagoda tree. A cheval mirror off to the side, the stand resembling a man’s fractured hips. All of these belongings out in the yard for a few days, quickly ruined by rain, so nothing had been taken away, yet long enough for graffiti to have been sprayed over the broken mirror.

no remedy

for

a dead sky

but

to

burn

The cafe played radio music. He waited for a song he liked by Chet Faker to end. He didn’t know what it was called and the words dissolved even as he listened to them, mattering as little as they had with Callas. Charles finished his coffee while it could still almost scald his tongue. Stepped back out into the winter morning—a wind sweeping in that felt as if it were on the verge of crystallising.

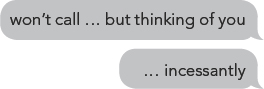

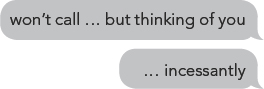

Across the road there was a For Sale sign in the yard with a sticker on it that said Sold. The white lace curtains in the window had long since become tattered. Used doilies now, he thought. He zipped up his jacket and pulled down his beanie. He checked his phone and was relieved, also distressed that there were no messages from his wife. Areti had told him last night not to call her— that she would call him at 10:00 a.m., after she’d talked with the doctors. It was nearly 9:00 a.m. He sent her a text anyway.

A mother was walking past the sold weatherboard with her two boys. She had an umbrella over her head even though the rain had stopped. Distracted by a phone call. Her boys wore unbuttoned rain jackets and were following her until they came across the old house with its ejected contents. They stole away. One of them climbed up onto a kitchen chair to stand on the dining room table. He waved about his head, swordlike, a dusting wand he had found in a tin bread box at his feet. The other kid picked up a teapot and looked inside. Poured rainwater into the open chest of a grandfather clock fallen on its back.

Their mother noticed they were not following. Called to them. Her voice overly harsh and loud in this affluent neighbourhood. And yet she was ignored. The boys imagined they would find something valuable or useful. Unrestrained, they might have wanted to explore the abandoned house as well. Charles imagined it was too dilapidated to be properly secured. Broken windows or locks and latches that no longer worked. Likely a demolition crew would be arriving soon. One of the kids picked up a glass paper weight and coiled his arm to throw it like a rock. She grabbed her boy by the wrist and dragged him away before he could take his shot at the cheval mirror.

Koschade read the graffiti again and thought fire might also be a remedy for the tumbledown. It was a strange notion that Charles couldn’t quite set out in a proper thought. Wasn’t it a shame that no-one would burn down the weatherboard? A fire couldn’t be controlled safely enough. Toxins from old construction materials might be released into the air. Bulldozers and excavators will arrive to break it up instead. The fragments will then go into a skip and be carted away to a tip and thrown in with the remnants of other houses and the general debris of the suburbs. The weatherboard had contained life for two or three generations so cremation felt more fitting to him than mutilation. Koschade took a photo of the mirror with his reflection behind the graffiti.

Areti texted as he sat in the car, warming his fingers at the dashboard heating vent.

It had rained overnight and in the morning, petering out for a couple of hours as if easing away, but it resumed in a deluge. Charles Koschade stopped beneath the branches of the trees arching over the road near Albert Park Lake. In a clearway on Union Street. He switched off the radio and the GPS. He listened to the water drumming on the metal of the roof, the rain creating a reverberating mist on the bonnet of the car.

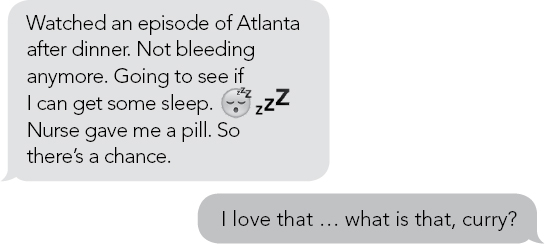

He read Areti’s text again. The emoji forced a deeper breath—holding it for a long moment. And then he laughed at himself for it. An emoji had never brought tears to his eyes before. Before Areti he’d always hated the silly little yellow faces attached to a brief message. Rarely used them himself. He scrolled back through the thread of messages to the previous one, sent last night at 10:35 p.m.

His response logged at 10:38 p.m. No reply from Areti. Maybe if he’d used an emoji Areti would have remembered it was a quote from Atlanta. It was the episode where Earn woke up next to his estranged wife—a joke about her morning breath. It’d been a while since they watched that episode. They’d both laughed.

The wipers weren’t able to clear the windscreen. He let them beat uselessly left and right. It made Charles think of metronomes and the descriptive names for the various musical speeds. This was a tempo for the setting beyond vivacissimo—whatever the word for frantic or desperate time was in Italian.

Pedestrians scuttled along the boulevard, holding onto their umbrellas, wet from their elbows down. Some didn’t have umbrellas. These people were tentative when they stepped out of their buildings, staying under the shelter of entrances for minutes, darting left and right as though searching for cover, and then decided on straight lines, striding ahead, drenched by the time they reached shelter.

A woman with a glossy magazine held above her head ran through puddles barefoot, carrying her shoes, although most of the women Charles could see along the footpaths continued to wear their high heels. They kept their umbrellas low over their heads. Make-up might be kept pristine on their emotionless faces. We need our emojis, he thought. Hang them from earrings; changed at a signal from an app that monitors our moods from a phone. A bloke could wear one from a lapel, as once a gentlemen would sport a flower—a natural emoji from the nineteenth century.

Traffic was slow yet ceaseless and chaotic with low visibility. Drivers leaned forward to peer over their steering wheels. One fellow drove by attempting to text a message and negotiate the chaos opening up on the road before him at the same time.

A pedestrian halted at Koschade’s car, intent on crossing right there, not at the intersection. She didn’t have an umbrella and her glasses were spattered with water. Ready to cross for a minute. Standing beneath a tree which sieved the downpour into fine droplets. When she noticed Koschade in the car she grinned and shrugged, retreating back to the footpath. It surprised him that a woman might still smile at a man sitting in a car looking at her the way he had. Her clothes were wet—clinging to her supple body. She was distracted, and the danger was in getting hit by a car rather than dealing with a sexual predator.

Charles felt grateful for the smile she gave him. He didn’t have the sort of face or body that would assure people he was safe. Easy enough for someone looking at him to imagine the monstrous. Other pedestrians walked along the footpath with umbrellas. Easy for us to imagine all things in anyone, he thought. Everything and nothing at once.

Koschade switched off his lights and turned off the wipers. Umbrellas and windscreen wipers were still the best we could do to cope with rain. It felt Old World, as though we hadn’t made any progress in dealing with rain for over a hundred years. Cars passed him by, slowly pushing through the storm. Charles blinked. Hadn’t been progress in some things for a thousand years. He winced and shook his head.

How bad would the weather need to get before all the drivers stopped? Cars would crash. Slow collisions that would not kill, that might only crumple metal at the edges, leaving fragments of coloured plastic from automotive indicators. Traffic would halt when enough vehicles had dodgem-carred to a clustered halt. There would be a great beeping of car horns. What might in other circumstances feel an expression of the indomitable human spirit now made him close his eyes and wish they would just stop. As useless a desire as wanting to dispel a storm by standing in the middle of the street and thrusting up outstretched hands.

The windows were turning white with the interior heat. Charles didn’t have any food. He should have had a meal in the cafe. Soon he’d be on the move again. Rain as heavy as this could only last five or ten minutes. Half an hour, max. There was a limit to how much water the clouds might hold. He couldn’t remember whether the biblical Flood had any scientific validation. Was it an event as factually established as the Ice Age?

When he was a child there were news reports that an archaeologist had found what remained of the Ark up on a desolate mountain somewhere obscure, perhaps Armenia. He was young enough then not to instantly dismiss it as religious idiocy. The report showed hazy pictures of the outline of what appeared to be a massive ship. The great vessel, the one that carried the human race whole, saved everyone—right there in a ruin outlined by snow-capped rock. It reminded him of the show Doctor Who and the magical police box. The space within the Ark might have been nearly as spacious, compacting every bit of life down to the paired essentials. As though the entire spectrum of existence could be folded like a fan in God’s hand, collapsed to fit between two thin pieces of wood—unfurled again in sunnier weather with a flick of the wrist.

He thought about how humanity found itself at some points in the life of the planet, as it was during the Ice Age, diminished to a few thousand people dotted across the entire globe. And how a ship really might have been enough to carry the whole of our species to a warmer, brighter world. Those starving, stumbling ancestors shivered in mountain caves instead, when the world froze or drowned down below. One of them waking from the Ark dream and whispering of a warm interior on a God-directed journey. A summer-bright expanse of grass—wide open fields with freshwater rivers flowing over pebbles— kept inside himself as secret as a soul. A murmured paradise in the darkness of that biblical dreaming.

Charles remembered a mandarin he had put in the glovebox yesterday before going to the hospital. He glanced at the digital clock on his dashboard as he peeled the fruit. About twelve hours ago now. If he went slowly enough the rain would ease away by the time he was done eating. Some fruit didn’t have seeds. The genetically modified ones. This wasn’t that type. Perhaps a mandarin was already a modified fruit, a mutant that was bred because it was more consistently pleasant and had a less acidic sweetness than an orange, but especially because of its easy-to-peel skin. Skin that just fell away. Skin that even a child could tug from the fruit within. Each segment had one or two seeds. They made Charles think of embryos nestled in a womb, drawn to the centre of the fruit and its umbilical connection down to the roots. He spat out the seeds into his hand, and when he was finished he chucked the mandarin scraps out the bottom of his open door, knowing it was not likely anyone would be able to see him litter. Or if they did, to report him. He checked his phone—found no messages and felt too bleary to look for distractions on the little screen, like searching to see if the great Flood was real.

The windows had entirely hazed over; he might have been buried in snow. Seeing ice and steam, thinking of the car as an igloo. When Charles was a child, he found out about the Eskimos and thought that’s what they lived in all the time—imagined towns constructed of igloos. A capital city with towers of ice. White palaces in the snow. But he’d seen pictures of their homes since, made from whalebone, driftwood and animal skins. Inside their huts were thick blankets and deep rugs with embroidered cushions. A space that might have been filled with the warmth and noise of children, of men and women calmly speaking with each other. He’d seen pictures only of isolated Inuit males when he was a child, alone in a wilderness of ice. He supposed the igloo was more often a temporary place to live in while hunting.

He could hear Maria Callas singing again. The phone was not on mute, because of Areti. She might call soon. The rumble of traffic faded. The soprano’s voice was coming through a white partition, reminding him of the kind of screen he’d seen around a shower. It was still cold, but where she sang there was steam, so he knew it was warm. She might be close. He wasn’t sure. She had the kind of voice that could carry right through the vast space of an opera house. He took a sharp breath when he felt a gentle pressure at his hip. Shoving forward—a slow mass of moving fur coming around from behind him. He couldn’t see clearly enough. The frost of white affected his eyes. Only the grey bristled back. A tail lowering and slinking towards the sound of running water and that naked voice. Because she’s singing, he thought, she won’t hear me if I call out to her. She was used to the swelling sounds of an entire orchestra moving her through an aria. She was used to being shouted at by audiences who adored her and those who despised her; they even threw cabbage heads at Callas. And maybe what moved around him was simply a dog. She might welcome the hound as a pet. Charles was worried now. If she stopped singing her silence would mean it wasn’t a dog that had found her. It would be a much more dangerous beast.

Charles woke when one of his back doors thumped shut. He wasn’t sure how long he’d been asleep. A man sat in the back of his car. Koschade blinked through an awful sense of angry confusion, like he was coming to after being KO’ed by a UFC fighter rather than rousing from a brief nap.

The rain continued to drum on the roof, so the man in the back of his taxi might have thumped on the window before entering. The new passenger kept his silence until he coughed into his shoulder. He might as well have stepped fully clothed in and out of a shower. Charles could hear him dripping onto the leather seat.

Koschade kept his hands on the steering wheel. He did not propel himself out of his vehicle. He did not pull the man out with a good grip of his collar. He did not throw him sprawling onto the wet bitumen. Still no hello. Not a word. And because the man behind him did not speak, Koschade could keep his hands on the wheel. At two and ten. He imagined the clock, holding onto it as if to stop this moment. The next second threatened to turn him towards disaster. So he focused on the wheel in his hands. He rocked with the desire to annihilate anyone who would enter his domain while he slept. He reminded himself where he was, that the rage couldn’t free him anymore—that fists could not save him out in the world.

“Where do you want me to take you?” he asked.

Koschade glanced at the man in his rear-view mirror. The passenger was as old as eighty. He sat in the back of the taxi, not responding, disorientation in his eyes. Perhaps he had lost his hearing.

Charles encouraged the surging agitation to dissipate. Breathing it out, as he’d been taught by counsellors. He took the last water from a thermos Areti had bought him when he got the taxi. Charles turned the heater on to full.

“Thank you,” the man murmured behind him. He lifted the palms of his hands to his forehead. Dropped them a moment later. “Thank you, Mr … Koschade,” he said, leaning forward to read his name from the dashboard identity card. When he turned in his seat to look at the old man directly, Charles noticed his passenger was shivering.

“I turned on the heater to clear the glass. Your warmth wasn’t on my mind.”

“My thanks wasn’t for the heater,” he said, taking a breath and dropping his shoulders. Gratitude for not being thrown back out into the rain.

“Sure,” Koschade said. “OK.”

His passenger had decided to avoid mentioning the restrained violence he’d seen in Charles. Acknowledging anger could sometimes draw it back to the surface after it had settled. Face to face, the man smiled—would have offered his hand if it was possible to shake hands.

“My name’s Thomas Avon.”

He had a smile that seemed pathetic to Koschade. Avon was old enough that he retained an outmoded code of civility. He removed an ivy cap that had soaked through to his grey head.

“My luggage is still outside,” Avon told him.

Charles nodded. It took him a few seconds to realise that this meant it was his duty to get out and put Avon’s belongings into the boot of the taxi.

The streets were rushing with oil-black water. The noise of the traffic was muffled and yet felt brittle in the cold. Trams moved up and down St Kilda Road—rolling along the wet rails like illuminated cargo containers on steel rollers, advertising Air Asia with a plane pictured lifting into an open, bright-blue sky, and the face of Cosette advertising Les Miserables playing at Her Majesty’s Theatre.

The windows of the taxi were translucent but the lights were on inside, and soon the heater would clear the glass. For now he could see the round shape of Avon’s head through the back window. It made him think of the seeds visible through the membrane of the mandarin.

An Australia Post van stopped in front of Koschade’s taxi. The driver got out and opened the side door to deliver packages to an office building, stacking them on a hand cart. In his free hand he carried a large bush of flowers and greenery in a gift-wrapped box. Heavier clouds rolled in low with a cutting wind. The postie appeared unflappable.

“Goddamn,” he said, shaking his head when he saw another working man in Koschade. “This fucking weather!”

Charles lifted his chin in reply as he closed the boot. He had placed two surprisingly heavy suitcases into the back of his taxi. Both had been dragged along the footpath on luggage wheels. The old fellow would have struggled to move the suitcases in and out of a tram, or even over a curb, unless he was stronger that he appeared to be. Koschade wondered how far his new passenger had travelled with his suitcases. Neither had flight tags. If he wanted to go to the airport he’d have trouble with the weight of his luggage.

“OK. So where do you want me to take you?” Koschade asked when he got back into the warm interior of his vehicle.

Wet and annoyed. Wanting to sleep again. It had turned into the kind of day that was so overcast it never felt like a real day—more of a continuing extension of the evening. The darkness of the night lifting for a few hours only to fall again. He’d taken a pill to go to sleep when he went to bed alone and another pill this morning to wake up enough for a shift behind the wheel.

“You can start driving. I’ll tell you where we’re going in a few minutes,” Avon said, blinking as if he were looking into a bright light.

“We can call someone for you … if you’re not sure.”

“Please drive. I have money,” Avon said, searching through the many pockets of a mackintosh and another coat beneath it. Beneath these two layers he was also wearing a suit jacket, and he had pockets to search through there as well. He might be as young as sixty, thought Charles. So dishevelled and distraught that he appeared older.

“It shouldn’t matter to you where I’m going,” Avon said. “All that matters is that I pay you for movement. Or, I mean to say, for transport. Makes me think of Emma Bovary in the back of a cab, asking the driver to continue without stopping, to go on for the entire afternoon. Different circumstances, of course. Odd comparisons sometimes go through your mind.”

“OK,” Koschade said, when his passenger began to search through his pants pockets as well. “It’s all right, Mr Avon. Your wallet is beside you on the seat … probably took it out of your back pocket when you first sat down.”

“Don’t know where my mind is at today,” Avon said. “Hope you won’t judge a man on his worst day.”

“I need to make a call before we get going,” he said as he woke his mobile. “OK?”

Avon nodded as he opened a plastic ziplock envelope he’d found in one of his pockets and withdrew a letter. He began to read it over as Koschade waited for his phone to dial Areti.

“Hey,” Charles said when the call went to voicemail. He felt awkward talking to his wife with a passenger in the back of the cab. It was rare for him to talk to anyone on the phone while he was working—privacy rather than propriety.

“It’s …” he looked at the time on his dashboard and saw meaningless digital numbers ticking over. “Suppose I was hoping you’d pick up and … we could talk … just quickly. You don’t have to call me back straight away or anything. Got a fare with me now anyway. Wanted to touch base with you … that’s all.”

“I like the smell of mandarins,” Avon said when he was certain the phone call was over. Koschade glanced in the rear-view mirror at his passenger, surprised by the vulnerability—that a man could say something so childish. Perhaps Thomas Avon had never been among men who would take such a comment as a radical statement of weakness. Avon placed his letter back into the ziplock envelope.

Koschade turned on the radio. Turned on his headlights, meter and GPS. He looked for a break in the traffic to do a U-turn. He wanted to take St Kilda Road rather than Queens Road, prone as it was to flooding when it turned into Kings Way.

“Please switch the music off,” Avon said. “I know it’s not loud. The murmur is even worse to me than clear sound. It’s a polite volume, so I’m not complaining, but I’d really appreciate you turning that off.”

“OK,” Koschade said and switched the radio off.

“I find it pleasant to listen to the car moving along the wet streets. When it’s cold and wet out, the interior of a car is a haven. Makes you remember what it felt like being a child and finding unexpected safety.”

Koschade paused when he heard sirens. They were getting closer and louder until the dull day was dazzled by revolving emergency lights as a fire truck and an ambulance made slow progress around Albert Park Lake towards the city.

“Did you want me to take you home? I don’t need an address. If we can get you to your neighbourhood, we can work it out from there. Or you can tell me your doctor’s name, a GP you go to, or whatever.”

It wasn’t only a question of age. There might be a disability or a sickness of mind. Thomas Avon might have a book with the numbers of doctors or carers who could be called in an emergency.

“The meter is running. The traffic is awful and I’m not in a rush. Do you have another person you need to pick up?” Avon asked, blinking as though he were speaking into the ferocious weather outside the windows.

“I’m not taking bookings today.” He’d decided to keep himself free to go to the hospital. Areti might call with a disaster.

It was distressing, the notion of driving endlessly as Thomas Avon said Bovary had done. Avon had forced his way into an out-of-service taxi so he’d have to be grateful wherever he was taken. And since the passenger had no destination anyway, if it came to that call from Areti, Koschade would drive straight to the Royal Women’s Hospital. Avon could get the fuck out wherever and whenever he chose.

“It’s an uncommon day,” Avon said. “Let’s not hurry about beneath those doomsday clouds outside.” He opened his wallet as though he might pay in advance.

“That’s fine.” At least it wouldn’t be another five-minute drive as it had been with the MMA fighter. This is the job, Charles reminded himself.

“It’s not about a destination, it’s about the journey.” It was a joke he usually murmured only to himself. The “journey” was what paid his wages. Koschade was frustrated by the confused, open-ended nature of this fare so he didn’t smile. Avon acknowledged the joke with a grin and a nod of his head.

A woman with a thin white cane stood at the intersection of St Kilda and Toorak. She had a sign on her chest saying she was blind. Her gaze was downcast but not unusual. That was why the sign was necessary. She didn’t have rolling eyes or irises pointing in different directions. She walked straight across the road with her cane tapping the wet bitumen. She didn’t need a seeing-eye dog—she must have at least enough vision to see amorphous shapes forming about her, a corridor of shadows.

Koschade thought about a story he’d heard inside, about the Buddha. A counsellor taught the inmates about meditation and she said her favourite story was from the end of the Buddha’s life. Surrounding the old man, sitting in mediation, were many people whose lives had been transformed by his words. They knew that soon the Buddha would be gone and before he died they wanted to understand him—and whether he was the son of God. An angel or an avatar? Some kind of superman? He shook his head at every suggestion, eyes and mouth closed. Eventually a woman who was not one of the Buddha’s followers, there simply to wash clothes, asked what the deal was with him. He told her he was awake. That’s all. Awake. His final spoken word.

Charles imagined people asking this woman, out and about in a storm, Are you lost, are you dumb, are you bereft, are you lonely and alone, are you forlorn?—and she might say, I am blind. And if the Buddha’s insight was that there was nothing more miraculous than being fully awake, the blind woman would point out that there was a great general blindness. We saw what was around us in a small sphere only a few metres in radius, most of the time, beyond which were receding shapes and forms that quickly became a haze of unknowns, gathering again in delicate shadows that could nevertheless run us down in the street to leave us dead if we weren’t careful.

His phone pinged with a text from Areti:

A mock-panic look on Areti’s face. Behind her were new bouquets and vases of flowers. Also plates of baklava and almond biscuits with icing sugar—Charles couldn’t remember what those were called. The selfie video with two women in faded black dresses was brief. Both her grandmothers had stopped to smile as though for a photo, had quickly resumed bickering as Areti snuggled in between them. Making light of the situation, but he could see real exhaustion and worry in her face. Koschade sent her the image of himself reflected in the graffitied cheval mirror and started to text her. Traffic began to flow so he switched the mobile to sleep.

He already regretted sending Areti the selfie. He’d been smiling like a fool. He had hoped to make her laugh with a radical contrast to the mirror’s grim message. Beanie pulled down over his ears, miserably cold, and yet a wide hick grin on his face. Maybe he would come off more as a psychopath with a crazy message about dead skies and burning things down.

“Have you seen that they’re trialling driverless cars now?” Avon asked. “A cyclist got killed recently by an automated Uber. So they’ve stopped for the time being.”

“Probably just a bump in the road.” Koschade glanced at Avon in his rear-view mirror. His passenger acknowledged the joke with a grimace.

“OK, but how does that make you feel?” Avon asked. “Soon you’ll be made obsolete. If not by Uber, then by automated cars.”

“This is not my life. A way to make money is all it is. If they have computers driving cars I’ll make money another way.”

“Which way?”

“I don’t know. How much time do I have to decide?”

No point in going through his hopes and ambitions with Thomas Avon. Exposing them to a passenger’s gaze always made Charles feel naive and desperate. He ceased to be a driver and became a dreamer instead. A Yiddish proverb passed through his mind—that the best way to hear God laugh was to declare your plans.

“If it’s going to be ten years before those driverless cars take over, I’ll probably want to do myself in anyway … if I’m still driving a taxi.”

Koschade had thought it was a random anecdote, yet Thomas Avon must have been looking over the median strip into that lane of traffic as the NGV came into view. A cyclist lay on the ground beside a car with hazard lights flashing and an open door. The driver crouched over him, talking to the dazed cyclist on the wet road. A precarious situation. The vehicle was stopped in a no-standing zone outside the VCA. The cyclist had been doored and the driver stood over him, waving the traffic to continue flowing around them both. The cyclist rose to his feet with some assistance and managed to hobble over to the nature strip.

“They’ve stolen the Pathfinder’s hammer again,” Avon said.

“What?” Koschade was bewildered by the strange sentence.

Avon wasn’t concerned with the accident anymore. He was looking in the other direction, towards the Queen Victoria Gardens—at a bronze statue of a man on the back of his heels, straining in a static moment, within the spinning blur of an Olympic hammer throw.

“They stole his hammer?” Koschade asked. “I know it comes and goes. I thought it had something to do with maintenance.”

Traffic on Princes Bridge was often terrible but it became diabolical when it rained. He checked the BoM site to see a red-orange mass sweeping out to the eastern suburbs on the radar. Blue-white waves of cloud were rolling in from the west over the rest of Melbourne—so dense he couldn’t make out Port Phillip Bay beneath.

“A grandiose gesture manufactured from bronze. So why not have a laugh?” asked Avon. “Transcendence tripped up. I’m sure there’s an amusement some feel in seeing a noble image rendered ridiculous. Because you know that in the very next chaotic moment, for the hammer thrower without that leverage, there would be an overbalanced spin and crash. A man struggling against the limitations that bind us on all sides becomes an arrogant desire for power, from the despoiler’s perspective. They can chuckle because all he is now is naked and fragile.”

A cyclist zipped around the traffic inching along Princes Bridge.

“Wonder if those vandals ever replaced the hammer with something else,” said Charles. “I’m thinking of that Banksy image with a masked rioter lobbing a bouquet of flowers instead of a Molotov cocktail.”

When they neared Flinders Street station Avon told Charles to take a left. Traffic flowed more freely after the turn and neither spoke for a while. They went down Flinders Street and kept going until they crossed over the Charles Grimes Bridge. Rain swept in hard against the windows over the Yarra but it was no longer a storm front. Avon directed Koschade under the West Gate Freeway on Montague Street. It was almost noon and yet each car they passed drove with switched-on headlights. Avon asked Koschade to take Pickles Street until they reached the bay.

The Spirit of Tasmania was securely docked to their right at Station Pier. He had seen the ship when it broke its moorings recently, during a bad storm, crashing sidelong into the beach. One of the most unnerving things he’d witnessed. A pristine vessel, as massive as an ocean liner, bobbing on the surf like sea junk.

“Drive towards Frankston, please,” Avon told him at the Beaconsfield Parade intersection.

“Is that where you want to go?” Charles asked. “Frankston?”

It would be a long drive back to the hospital. In this weather it would take over an hour. Perhaps two. Charles told himself that whatever the outcome, Areti was already where she needed to be for help—and that he was himself utterly useless.

“Let’s drive along the beach for a while. We’ll stop well before Frankston,” Avon said.

Near Catani Gardens they saw a digital billboard. A woman with long, streaming hair was swimming in a bright azure ocean. Then a young man was running in the sun, alongside a luxury yacht—glittering with silver and white metal. The swimmer was about to reach the surface as the man dove into the water. A sudden split screen in slow motion showed the two people moving towards each other. There was a white-capped wave breaking into particles that fused into a swirling pulse of energy after the diver and the swimmer crashed. It all settled into the shape of a perfume bottle, around which wound a red satin ribbon with the word Heatseeker.

“It’s a slow explosion,” Avon said when they started moving again. “Everything drifting out in a million directions. A wonder the world doesn’t disintegrate with all those incalculable vectors. My son was a mathematician. He would have been able to explain with one of his theories how it all continues to cohere despite the ricocheting shrapnel we feel. I’m sure that’s simply my perspective. Your own thinking plays out in what you see. What do you think?” Avon was gazing out the window at the long desolate boardwalk along St Kilda beach. Perhaps he wasn’t really expecting an answer.

“A world of traffic,” Koschade said. “Some days I barely see the cars. It’s all just moving lights over a black ribbon.”

They didn’t talk for a few minutes. Charles felt as though his passenger was was waiting for him to say something more. To prove he wasn’t an outmoded automaton at the wheel of a taxi randomly throwing out barely understood words.

“Do you remember the first time someone showed you a picture of the planet and told you that’s where we live? My parents blu-tacked a poster of the Earth on my wall and thought I would be delighted. I wasn’t—told them it wasn’t true and shook my head, crying every night for a week, even when they pulled that poster down. I believed them but I said I didn’t because it scared me that we lived on a bubble. It would be so easy for that bubble to pop. Around that time, a neighbourhood friend I played with died while mucking around with firecrackers—so that probably had something to do with it. As I grew up, satellites gave us better images of the planet, and it didn’t look like a bubble on a shitty poster anymore. At some point though you realise that there’s a layer of gases drifting over a vast mass of moving rock, trapped in an orbit around the sun. What we’re a part of is an incredibly thin membrane really, when you take in the size and density of everything else trapped by the same star. So it still feels precarious, but I reckon we prefer images of heaving oceans, billowing clouds filling the skies, fields of rolling grass, making everything appear endless.”

They passed the Brighton sea baths. Avon had been leaning back into his seat, face to the ocean, turning to Koschade when he stopped speaking. He made a guttural noise with a nod to indicate he was still listening.

“About that same time I came across a story you might have read—‘The Little Match Girl’. There was a line where the freezing girl says, ‘Someone is dying now.’ And then she thinks, ‘When a star falls, a soul rises up to God.’ I know Hans Christian Andersen never saw the planet from the moon or from satellites. If he had, he would have understood there is too much death on the planet to wait for shooting stars. Instead, I imagined each life was a bubble and the oceans were like water in a pot beginning to boil. Each one of those bubbles was the death of a person. And then I thought of milk and the way the whole thing begins to foam when it’s forgotten … it boils right out of the pot and turns everything black.”

Charles stopped at a pedestrian crossing. They were so near the sea he could feel the cold of winter ocean air coming through the glass. A father crossed the street, leading his daughter over to a fish and chip shop. He had another child strapped to his chest in a Babybjörn. All of them wearing beanies, mittens and scarves. The girl had a Rhodesian ridgeback on a leash. She tied the dog to a fence and it strained on the leash to follow her.

The girl pointed at graffiti before they went into the shop for their lunch. Tall temporary fencing ran across a piece of land next door. The face of a lion had been woven into metal fence links with pink plastic lengths of fabric or string. The heads of various animals had been appearing around Melbourne for years. Some kind of graffiti, yet as oddly innocent as they were precise.

Beyond the fencing was a large rectangle of open grass. The land had been cleared of any remnants of whatever structure had stood there before. Even the foundation. The grass had grown thick, above knee height—a level cut showed it had been attended to by a gardener. Wildflowers like everlastings had taken root. In these affluent areas it didn’t seem as though the land had been abandoned, that something had stalled financially, but rather that a piece of land long occupied had been cleared, the ground opened up to breathe again. A preparation for new life.

The Rhodesian ridgeback started barking for its owners and Charles realised the light at the crossing had gone green. The driver behind him gave a polite toot of her horn. Avon looked half-asleep. The girl came out of the shop to pat the dog as Charles pulled away, an apologetic hand raised to the polite driver behind him. He’d come to expect rage from drivers delayed by even a second’s hesitation.

“When my son was young, we had a dog,” Avon said. “I never wanted a dog. My life was already busy enough. I didn’t want to look after anything else. Had all I could handle looking after my son and my wife. She got sick. Parkinson’s, so it was long and hard. He was such a quiet, sweet boy and it was rare for him to go on about something he wanted week after week. I told him that he could have a dog if he proved he could look after himself first. Because if we got a dog it would be up to him to look after it. And it turned a switch in my boy’s brain because he began to make himself breakfast, made his own school lunch, made his bed and dressed, brushed his teeth and combed his hair without needing to be asked. Walked himself to school when most kids still needed their parents to take them. And he was only eight. So after a few months I said yes, we’d get the dog and he chose a cute little Rottweiler. My boy called him Coper. Named after Copernicus. I got a call from my son one day when I was at work that there had been some trouble at home. And that Mum was in hospital. She’d been attacked. So I went to see her and it turned out they were eating ice-cream in the afternoon. A few hours after lunch. It was summertime. The dog hadn’t eaten much. His can of dog food sat in his bowl, barely touched. Probably because of the heat. I don’t think anyone gives ice-cream to a dog. Tommy and my wife were watching a film on the couch, laughing. And the dog must have felt that he was being left out. That they were eating without him and mocking him. It was the comedy they were watching. When Coper attacked my wife, he tore her face apart. We had to get a plastic surgeon to sew her ear back onto her head.”

Avon had the palms of his hands to his eyes again. When he dropped his hands, Charles could find no sign of emotion for him to determine what to make of the anecdote. He had found that passengers might offer a story from their life because the separation and anonymity of a taxi were as intimate to them as a confessional. Mostly they bored him. Occasionally Koschade was interested enough to play along, as though he could offer anyone absolution for anything.

“Did you put the dog down?”

“No, I didn’t,” said Avon. “When I got home from the hospital I was angry. It’s a Rottweiler, for God’s sake. Cute as hell when they’re puppies but it was too big and wilful a dog for the little place we had in Elwood at the time. And I should have had it properly trained. So what could I expect? I blamed myself for buying a beast for a little boy to look after. Tommy wanted a dog, and that was fine. It was up to me to choose a suitable pet. Not simply the one that caught his eye. You want your kid to be happy, right? Yet he would have been pleased with another choice. Any dog would have been Copernicus. He thought up the name before we even went to the pet store. I was planning on putting the dog in the back of the car and taking him to my brother’s house. He had a big property over in Montmorency. He didn’t have kids and he already liked Coper. They got on well. Every time my brother came over he’d stop off at a butcher’s first to get a big bone for the dog. Tommy was in his room when I got home, going over his homework. Doing his maths. He was so quiet I couldn’t shout at him. I knew cold silence would hurt him just as much, so I wasn’t being too kind. And it would be better if I took the opportunity to take his dog away as punishment. The dog was dead by the time I got over to my brother’s house. Blood in his mouth. A handful of rat poison rolled up in some mince, given to him by my boy while his mother was in hospital.”

They were passing Sandringham Football Club. Avon abruptly told Koschade to take the next right, down Jetty Road.

“So damned awful,” Avon said. “I don’t know why when I think about how lovely a boy he was, I rarely think of the things he did that were sweet. I was horrified at the time. I worried that he’d grow up to be a sociopath, but he was never a violent kid—or man, for that matter. As things have gone, I think he showed his mettle that day. People don’t even know what the word means anymore. Made me proud, how resolute he could be. I’m still horrified. What a thing that must have been for him to see. That Rottweiler mauling his mother.” Avon wasn’t tearful yet had the palms of his hands up over his face again. He murmured words to himself as he rubbed at the flesh around his eyes and mouth. All Koschade could make out in the smothered words was “my dear woman”.

They had reached a car park overlooking the bay. The beach ran south for two or three kilometres. Red Bluff was barely visible in the overcast haze. The steep cliffs rose thirty metres into the air all the way out to Black Rock. The bay roiled with shallow surf below them. Hundreds of boats and ships bobbled in their berths at Sandringham Yacht Club to their right. Nothing on the water as far as the ragged horizon.

“Is this where you wanted to go?” asked Charles with his finger on the meter. Avon didn’t answer so he turned to him and asked, “Is this your destination, Mr Avon?”

“It’ll do,” he answered. “You can leave the meter running. The weather might improve a little. I’m meeting someone here soon and still have some time to spare.”

“Do you mind if I put some music on?” Charles asked. The rain was coming down again in sheets.

“Yes, put some music on, please,” Avon said. “Do you have anything good?”

Koschade’s phone was dominated by music a man Avon’s age was not likely to deem “good”. Areti also liked opera so he decided to put Maria Callas on again. Thomas Avon looked like the kind of bloke who thought opera was proper music. He didn’t respond to the choice of tunes.

Charles couldn’t hear the music very well over the rain pounding on the roof and windows but her voice rang out clearly. It was the music that Koschade found dull. The sharp voice of Callas by itself was striking in the muffled interior of the taxi. She sang in a way that brought a fleeting sense of warmth and illumination to the dull, cold light of the dreary afternoon.

As soon as Avon decided to get out, Koschade would drive to the Royal Women’s Hospital. The meter was running. He’d earn enough from this fare that he wouldn’t need to stay on the road today. He turned off all his lights. He wanted to rest as well. When Areti sent him the selfie video from the hospital he thought he’d seen her worry and exhaustion despite the smile but it hadn’t occurred to him that his photo would have shown her the same.

“Put the music up a little, if you like,” said Avon. “Loud would be good. The rain’s drowning out poor Maria.”

It surprised Charles when he heard Callas taking breaths between her words. And he wondered at the surprise. Callas wasn’t meant to be a woman on a stage somewhere being recorded. If she transcended, she became improbably ethereal, as unreal as an angel. Yet Callas wasn’t an instrument hitting notes, as precise as a piano, as clear as a trumpet. She was a woman opening her chest to let out the confused noise of her life as loudly as she might, and allowing that noise to be transformed in the thin air around her, into clarity, into purity, a fusion of the world and its spinning time, never ceasing to be a person reaching out to other people. Maria Callas would now be a collection of bones bound tight in desiccated skin, in a box somewhere below ground.

“The weather is awful. You’ll get sick out there by the water with that wind,” Koschade said when the song finished.

“There’s no such thing as bad weather, as the saying goes. Only unsuitable clothing,” Avon said. “And I’ve got layers of warm clothes, Mr Koschade.”

That expression made Charles think again of the Inuit pictures he’d seen, animal skins and fur bound tight over every part of the man’s body, leaving just the eyes, nose and mouth exposed to the white desolation around them.

“Do you mind if I smoke?” Avon asked. Koschade looked in the rear-view mirror to see if he was serious. Avon already had a cigarette in his mouth—was ready to light up as though it were 1960.

“Only if you’ve got one for me,” Charles said.

He reached out and took a cigarette. Avon passed him the lighter.

Koschade’s phone lit up with an incoming call. He turned the music off when he saw it was Areti calling. “I have to take this,” he told Avon.

“Hey,” Charles said into the phone.

“Hey,” Areti said, as if it were a regular conversation.

“Sorry I haven’t come over today,” he said, glancing at Avon in the mirror. Koschade got out of the taxi and went to the boot where he had an umbrella.

“I don’t need you here,” she said.

He didn’t know what to say to that. The windows of his taxi were beginning to fog again. A local wearing a long frog-skin camouflage rain jacket had been walking along the beach and was now climbing up the many wooden stairs that led to the car park. He had his hood down and walked past Koschade without looking at him. Strode away down Jetty Road.

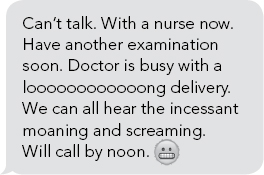

“Sorry. That was a nurse asking me about lunch,” Areti said.

“I’m out in the rain so I didn’t quite catch your order,” Charles said.

“Why are you in the rain?” she asked.

“Fuck the rain, Areti.” Louder than intended. “What did the doctor say?”

“It’s OK. We’re OK. There’s no bad news. I didn’t sleep well last night. The maternity ward is the worst place in the fucking world for a good night’s sleep. Babies crying at all hours—it’s sleeping with a snooze alarm on the whole night long. There was a woman who had an early morning drama with her baby suddenly going blue and beginning to choke on amniotic fluid it still had in its stomach from birth. And then my whole family comes over …” She let out an exasperated sigh. “So I’m wasted and trying to sleep.”

“You sound tired. We can talk later. I’m coming over soon.”

“I don’t need you here, honey. We’ll sit on the couch in the lounge room soon and I’ll put my head down on your chest. So there’s no rush to hospital world. I’m going to sleep now, I think. I’d sleep better though if there was some good news. It’s OK. I wish we could have good news. All they do is delay the bad news. That’s me being pessimistic. The bleeding has stopped. They say it happens and it’s not always a disaster. So we’re OK. Our jelly bean is doing well again. They put her up on the screen, said she was sucking her thumb. Maybe the jelly bean is a boy. It’s so hard to make him out in all that static. Looked like he was waving. Not drowning. I suppose he’s not a little boy sucking his thumb. He’s just a jelly bean with a mouth and fingers. I could see the shape of him. He looks fine. Calm and relaxed. And then they found his heart and it’s beating so fast—double time. And they say that’s normal, but all I can hear is the thump-thump of that excited little jelly bean and I don’t know what more I can do to keep him safe.”

Charles heard his wife crying. He fell into silences when they talked about the baby. That was so common Areti barely expected him to speak. She sometimes asked him if he really wanted a baby and he told her he did. He wasn’t lying even though she told him he was. Areti had already had two miscarriages. He couldn’t imagine what a third one would mean or what it would do to her.

“We’ll be careful,” he said. “And I’ll be there soon. Trade you vodka if you haven’t eaten all the baklava already.” There hadn’t been vodka for years.

“I’m going to have a nap,” she said. “Posted that remedy for a dead sky picture of you on Instagram and someone said something about American Psycho. Christian Bale was hot in that film so I liked the comment.”

Koschade got back into the taxi. He put the phone to sleep but reached behind his seat to offer it to his passenger.

“Do you need to call someone?” he asked Thomas Avon. “If you’re meeting someone here or whatever.”

“No, it’s all right. I’m about to leave. Simply bracing myself for the the cold,” he said.

“It’s fucking cold out there,” Charles said. “I’m shivering. I can take you somewhere else while you wait. A cafe nearby? Or we can sit here. Money in the bank for me, either way.”

“You took my lighter with you when you got out, before I could light my cigarette,” Avon said, holding up his unlit cigarette. Koschade apologised and they both lit up.

“I’ll leave as soon as we’ve smoked these,” Avon said. He drew back deeply on the cigarette. Blew smoke out with a sigh of pleasure.

“Haven’t had a cigarette in ages,” Charles said, feeling light-headed and trying to suppress a cough. “Had to quit for the missus.”

“Used to bring my wife and son down to Sandy beach some summers,” Avon told him. “Kind of against my will most of the time. Always felt the sand and the water were more mess than it was worth. And sunscreen was such a pain. You get a boy near the ocean on a hot day and all he wants to do is run into the water. The sand is scorching so you have to unpack and roll out a beach towel first. And then the sunscreen has to go on before the water as well. All the while my boy’s trying to escape my clutches and get into the ocean, and I’d be swearing under my breath. Barely felt his arms and legs in my hands. And then there was the face to do, asking him to close his eyes so the sunscreen wouldn’t blind him. Hated the feeling of that kind of oil on my fingers. Just when I’d rubbed it all off and was ready to relax, my wife would remind me that I needed to put sunscreen on her back.” Avon spoke as if that might have been a joke at some point but it had lost its humour for him over time.

Koschade grew up in Mildura, so he had few beach experiences to speak of. Thomas Avon gazed at his hands as though he could still feel sunscreen stickiness … or perhaps now all Avon remembered were the lithe limbs of his son wriggling in his hands and the radiating warmth of his wife’s summer flesh.

“A Melbourne beach in winter can give you a sense of proximity to the South Pole,” Avon said. “Not that it’s that cold. It’s not Copenhagen. There’s something crystalline that settles in the back of your lungs when you breathe out there by the bay for a little while. Like a white dust. There’s a particular wind that comes across the water this time of year. We should have a name for it, as they do for the sirocco in Europe. Have you heard of the sirocco?”

“I’ve heard of it. Never been overseas,” Koschade told him.

“Once or twice a year the sirocco starts up in the Sahara, crosses the Mediterranean, drawing up water as it does. It can be ferocious, hitting the coast of Italy with what they call blood rain. All the desert sand the sirocco has carried over the sea. If ours came with blood we would have a name for it here as well. No-one really thinks about Antarctica. If they do, I suppose they imagine an iceberg the size of Tasmania. What do you think?” Avon asks.

“It’s just a place, really, for the hole in a desk globe,” Charles said.

“Twice the size of Australia. It’s an entire continent. All of it a desert despite the ice and snow. I can’t take in a place that big a little south of Tasmania. It doesn’t fit in the mind. Too much nothing. For most of the planet’s history, though, Antarctica wasn’t covered in ice. It was a regular continent about the size of South America. Might have been the best place for life when the oceans simmered with heat. But it’s been dead for a long time now.”

“They’ve got some bases out there for scientists,” Koschade said, stubbing out his half-finished cigarette and feeling compelled to add something to the conversation. “I think it’s too dark and too cold for people most of the year.”

“You can almost smell mountain ranges of ice. Then there’s some dust in the lungs from a nameless wind that comes across the bay. When you stand on the beach in a Melbourne winter you can feel that bone-white continent going on and on if you don’t forget it’s there.”

When he was in prison Koschade heard a climate scientist talking on the radio about the seas rising and wiping everything out again. “Again” wasn’t the right word. The scientist didn’t mention the great Flood and maybe that never really happened. The scientist talked about the unimaginable amount of water that had been gathered up into ice over in Antartica. Like God’s fist. The bloke on the radio didn’t say that—it was the image that came to mind as Charles listened. That fist didn’t make him think of a punch. It was the kind of fist needed to hold on to something. The threat was that the hand might open and let everything go. An open palm twice the size of Australia. Koschade never went to chapel and hadn’t contemplated any questions of divinity since he was a child, yet there was a thought he found oddly painful. We would never again be punished by God. We would simply be forgotten.

“Hard to imagine people reaching the South Pole not being upside down when they get there,” said Koschade, embarrassed that he might sound religious if he mentioned a fist holding back the flood. “I suppose they’ve got an actual pole down there to mark the spot.”

Avon finished his cigarette. Koschade opened his windows a few centimetres and turned on the heater to circulate the smoky air.

“If you can remove my luggage from the boot I’ll get going,” Avon said.

When Charles got back into the taxi after pulling out the two heavy suitcases, Thomas Avon paid him with a credit card. Closed the door with a hard push. Waved instead of saying goodbye. Pulled his two suitcases along behind him to a bench and sat down as though to take in the view. Avon looked robust enough for his age but hopefully his friend would show up soon.

Koschade drove back up Jetty Road and turned left onto Beach Road. He would have to stop to eat lunch. It was a long drive to the Royal Women’s Hospital. The traffic getting into the city would be bad—it would be absolutely dire getting out of the city to Flemington Road. He used to like a burger joint in St Kilda on the corner of Carlisle and Barkly. He hadn’t had much of an appetite for the last few weeks.

The wet umbrella sat on his passenger seat, dripping water. He knocked it down to the cabin floor. It popped open with a spray of rainwater. It was old and cheap and the latch on the thing was difficult to engage at the best of times.

His phone pinged. A text. He ignored it when he saw it wasn’t from Areti. For now they were safe. There was no bad news until he got to her ward. And maybe there would be no bad news for the entire evening and he would be able to take her home. They’d sit on the couch like she said. Watch another episode of Atlanta. He would lock the doors and keep the curtains closed, and he would feed her in bed, give her anything she needed to be comfortable. And the bad news might not come at all if they breathed and moved carefully.

He’d been thinking of the Little Match Girl again recently because of Areti. When each one of those matches was lit a whole world was illuminated, but the darkness that followed felt all the more dismally cold. Each match she struck brought her closer to the edge of her life. He didn’t know how to pray. All he could do was close his eyes and hope that this match might stay lit.

Koschade was annoyed by the wet umbrella. It continued to drip rainwater. He pulled over to the kerb so he could get out, close and return it to the boot. He thought about Avon. The back seat would still be wet from the rainwater he’d brought in with him on Union Street.

Was he an old fool going to the beach in this horrendous weather to reminisce about his wife and son in summers past? Just a fucking idiot with no sense whatsoever? And since he hadn’t seemed to know where he wanted to go when he got into the taxi, how likely was it that the old man would be meeting someone at Sandringham beach soon? Or at any time, on a day like today? Koschade really was no better than an automaton if he believed any of those things. He threw the umbrella back into the boot and got into his vehicle again.

The beach was empty. No cars in the car park. Heavy clouds were rolling in, black with more rain, allowing little sunlight through. No locals strolled the beach. Koschade found the two suitcases near the bench. One was closed and the other open. He saw what he initially thought were the parts of a machine. Found that it was mostly large pieces of metal, wrist-thick bolts and fist-sized nuts. None of the steel had the grime of having been used before in any kind of apparatus.

When Koschade looked around he couldn’t see where Avon might have gone. The beach was ragged with seaweed and the flotsam of a turbulent ocean so it didn’t reveal any footprints. Koschade went back to the taxi, unsure what he should do.

He couldn’t drive away. All he could do was move around the car park. He got out again and went down the wooden stairs descending to the beach. He waded across the wet sand and over to the water’s surging edge. He saw the top of Avon’s head disappearing below the black expanse.

Avon was not bobbing up and down in the water, the way a person normally would when hit by waves. His arms rose at each swell but his body moved forward without buoyancy. The waves swept right over him. They hit him, and repulsed his forward movement. He wasn’t swept back to the beach. He had brought his own ballast— weighed himself down with the pieces of metal from his luggage. All those industrial nuts and bolts. Three jackets with many pockets. In the pockets of his pants as well.

Koschade fell when he walked into the first heavy wave, taking sea water into his lungs. He’d never gone into the ocean fully clothed before. The weight of his clothes and the way they wrapped around his limbs and clung to his flesh made moving difficult. The wintery salt water sprayed up into the air by the surf became serrated on the wind, razoring any exposed skin. He was blinded for seconds. Stunned by the agony and overwhelmed by the thought that Thomas Avon had willingly walked into this. That he had sought out this pain—that he had wanted to move deeper into it. After a few steps Charles fell again, got up coughing. Took in so much sea water this time he thought he was going to choke.

He turned. There was no-one out on the beach. The car park up on the bluff was still empty but for his own vehicle. Koschade bobbed in the water. His taxi was up there with its lights on. Avon might have seen it and gone out deeper until he couldn’t continue walking. Until he ran out of breath.

Koschade turned again. He’d lost track of him. Avon had gone under. Charles stood there blinking and trying to clear his vision—watching the waves come in with such a roaring force of pain that it bleached his mind. He lifted his palms to his eyes. The corrosive pain in Avon that found itself resolved only in this flood of agony. All the pieces of metal, as nothing compared to the broken pieces of his love. So Charles moved further out to where the sea water broke over his shoulders in wave after wave. He didn’t know how tall Avon was; they had never stood face to face. Perhaps he was taller than Koschade. Charles knew a brain began to die after two minutes without air.

He crossed from one sandbar to another—he felt them below his feet—and then swam across another trench. He moved out into deeper water, waves crashing over his head, one after another. Below the water he found brief moments of relief from the roar of the wind. He had to come up again. Took another gulp of sea water. Hacked it out. Gasped for air. He wasn’t a great swimmer—only used to the slow-flowing Murray and the public swimming pools in Mildura. He wasn’t sure what he would do with the body. He didn’t know how to give mouth-to-mouth. Charles would try to breathe into Avon if he found him. Sea water would fill the man’s stomach and his lungs.

He saw the top of Avon’s grey head, just above the water. Palms out. Not too far away. He’d crossed over another sandbank; would soon be out in the water that would drown him. He’d chosen a difficult death. Wanted it to come in waves, to slowly bleed him of all his strength. To tear the sunlight from his mind one memory at a time. Koschade knew there was no point in shouting out to him. If Charles called out, Avon would step right into the swell and be gone.

Koschade swam and walked as best he could, reaching Thomas Avon in his last moments, grabbing him by the collar. He pulled him back towards the shore. As soon as he had a good hold he felt a surge of fury. He was brutal as he dragged the man behind him, swearing at him as he went. As soon as the water was waist-height, Avon found his strength and balance again. He had talked about the Pathfinder being naked and fragile—and had then covered himself in layers of fabric and metal. He used the weight he’d brought with him into the ocean to stand his ground.

Thomas Avon began to throw punches. Battering Charles with everything he had left. Both of them were wordless in the roar of the ocean. Koschade tried to grab him but Avon’s limbs were wet with sea water. He stepped back, fell when a wave came and knocked him over. Stood again when Avon attempted to move back into deeper water. He took Avon’s punches as best he could. The man would wear himself out. He had already used most of his strength fighting through the waves. When Avon couldn’t raise his arms anymore, Koschade moved towards him and held him as boxers did in the middle of a round.

He could hear Avon’s hoarse breath wheezing out of his exhausted lungs. The wind scoured their faces. For all the struggle, neither of them had any more body heat. Flesh felt as cold-blooded as fish. It was easier for the two men to stand in this odd embrace, continuing to be hit by wave after wave. Koschade only loosened his hold when he felt the man wobbling, about to drop. He hauled him again by a flap of the mackintosh and got him back to the sand.

Avon stumbled. Picked himself up, coughing out water. They collapsed on the beach together. Turned to sit when they could, watching the sea water washing over their shoes. Charles no longer heard the noise of the wind or the waves. He was so numb he couldn’t feel the cold. Around him he saw the static of a midwinter’s day. He heard a double-time heartbeat. He closed his eyes to listen to it. Thomas Avon leaned forward to vomit out salt water.

“Where do you want me to take you now?” Koschade asked him. He could barely talk, his teeth were chattering so violently.

Koschade slapped the man’s back to help him empty his stomach.

“The meter’s still running so you’d better make up your mind soon,” he told him.

“The meter is still running?” Avon asked as he looked at Koschade. He was having just as much difficulty talking. The man nodded with the grimace of a smile to indicate he knew it was a joke. “We should get moving then.”

Avon couldn’t stand. Koschade had to pull him to his feet. The old man took the pieces of metal out of all his pockets. Nuts and bolts from some massive machine he didn’t need anymore. The last thing he threw away was the note he’d placed in a ziplock envelope. Avon removed the letter from the protection of the plastic and let it drop into a surge of water that swept passed their feet.

Charles was trembling, only saved from dropping by the need to keep moving and get back to the heat of the taxi. Tremors ran through his body. He couldn’t keep his head steady on his shoulders.

Soon they’d be warm again. They would both sit inside, dripping on the seats. There would be that moment Avon had mentioned before—of feeling like a child finding unexpected safety. They might listen to Maria Callas sing again.

He thought of the Little Match Girl as he and Avon trudged through seaweed across the corrugated beach back to the taxi. The headlights of the vehicle were on, its doors open, and the interior illuminated as well. The engine was running and the heater was on uselessly. Might have been stolen—not likely on a day such as this one, when anyone with any sense was inside.

They walked up the wooden stairs up the bluff to the car park with difficulty, one step after another. Thomas Avon thanked him for the help.

It occurred to Charles Koschade that Andersen didn’t need satellites in the sky to see the Earth when he wrote that story about a poor girl freezing in the winter streets of Copenhagen. Those shooting stars, each one a soul, aren’t what we see at night. We don’t see anything anymore— living in cities that obscure the stars with light pollution. He was looking further out at the play of light showing through a black dancing ribbon.