5

Lafayette Flying Corps

A Bet

By mid-summer, Bullard was frequently given leave from the clinic so he could visit Paris. One afternoon, he stopped at a popular hangout for artists, La Rotonde, on Boulevard Montparnasse.

Two painter friends were already waiting for Bullard. Gilbert White, a successful American painter from Michigan, sat with Möise Kisling, a prosperous expatriate Polish painter in Paris. He had recently received a $5,000 inheritance from the first American pilot to die for France, Victor Chapman, who had been a mutual friend of Bullard and Kisling before his plane was shot down during a dogfight near Douaument. The two painters waved Bullard over to their sidewalk table.

Another American friend from Mississippi, Jeff Dickson, soon showed up and joined the group. The waiter brought a round of vermouth cassis drinks for everyone, and the four men engaged in lively discussion about art and the war.

“What are you going to do when you get out of the hospital?” Dickson asked Bullard.

“I’m planning on going into the air service.”

Dickson snorted. “No way.”

Kisling set his drink down. “What exactly do you mean by that crack?”

“You know what I mean,” Dickson answered. “Eugene’s colored. There are no Negroes in the air force. There’s no way he’ll ever become an aviator in France or anywhere else.”

Kisling raised his voice. “If Eugene says he can become an aviator, I believe him.”

Dickson turned to Bullard. “I’ll bet a thousand dollars you can’t.” He paused. “No, make it $2,000.”

“You know that I don’t have that kind of money,” Bullard said. “But I will become a flyer.”

When Dickson excused himself to use the restroom, White turned to Bullard. “Eugene, if you say you can do something, Möise and I know you can. We’ll cover your bet.”

The next day, the foursome met once more at La Rotonde. Bullard pulled out $2,000 given to him by his friends and laid it in front of Dickson. “I’m taking you up on your bet. The next time you see me, I’ll be an aviator.”

Dickson blanched. “Okay, okay. I figure it’s a pretty safe bet, anyway. No colored guy is going to fly.”

“I’ll hold the money,” White said.

Everyone clinked their glasses together, agreeing to the terms of the bet.

Bullard was now on a mission. The next day at the clinic, he found Commandant Ferrolino. Bullard announced that he was ready to leave for the aviation corps.

A French Air Service ID photo taken early in Eugene Bullard’s air training. On the left, he’s wearing an insignia of the French Air Service; on the right is his Croix de Guerre awarded for valor at Verdun.

The commandant kept his earlier promise and contacted officials in the French Air Service on Bullard’s behalf. A week or so later, Bullard opened a telegram. He could hardly believe his eyes. He had to read the message again. And again. It was true. He was ordered to report to Caz-au-lac on October 6, 1916, for training as an aircraft machine gunner.

Bullard could hardly wait.

Penguins and Other Planes

The morning of October 7 arrived. Bullard, sound asleep in one of the barracks at Caz-au-lac, was suddenly awakened by reveille. Eager to begin aviation machine-gun training, he leapt out of his bed, cleaned up and joined the other men forming outside. He recognized Edmond Genet, one of his fellow soldiers from the Foreign Legion.

“Edmond,” Bullard said, shaking his friend’s hand. “What’s a legionnaire doing here?”

“I’m now a pilot in the Lafayette Escadrille,” Genet replied. “And I’m here to learn how to shoot a machine gun, because I fly a one-seater aircraft, a Nieuport. I have to do everything myself—fly the plane and shoot at the same time.”

“The Lafayette Escadrille?”

“Yeah, it’s an American volunteer squadron.”

“And you’re a pilot?”

Genet smiled. “It beats the trenches. And I get paid more than an aviation machine gunner—$10 more a month.”

Bullard thought for a moment. “I never heard of the Lafayette Escadrille, but for $30 a month, I’d just as soon be a pilot, too.”

The next day, Bullard visited his captain and announced that he’d rather become a pilot. The captain promised he would forward Bullard’s request to his superiors.

While waiting for his request to be answered, Bullard practiced for the next two weeks, shooting machine guns at moving targets while trundling along a track in a mockup of a cockpit. He fired at targets from motorboats. And to determine the accuracy of his shooting, he even fired at real planes flying overhead, using guns that shot photos—not bullets—whenever he squeezed the trigger.

Bullard’s orders to become a pilot finally came, and he started his pilot training at an aviation school in the city of Tours. His first assignment was to learn how to handle a Blériot monoplane on the ground. The Blériot had a three-cylinder 45-horsepower rotary engine and wings only about five feet long. The pilots called them “Penguins” because they couldn’t fly.

The Blériot Penguin flightless monoplane with clipped wings and a low-power three-cylinder engine was used to train pilots in engine control and ground handling.

A group of veteran pilots and Penguin graduates gathered near the airfield and joked as the Penguins were brought from the hangars. Bullard realized that they wanted to watch the new trainees in their Penguins. And he also noticed their faces—all smiles.

After crawling into the cockpit, Bullard buckled in and fastened his helmet. One of the French instruction monitors showed Bullard the Penguin’s simple controls: rudder pedals, a joystick, and an ignition cut-off switch.

Bullard was instructed to taxi the Penguin in a straight line. “Give the machine full gas,” the monitor instructed. “Get the tail off the ground at once. Use your rudder pedals to keep it going straight.”

A mechanic yelled, “Switch off.”

Bullard made sure his ignition switch was off. “Switch off.”

The mechanic flipped the propeller over a couple of times to suck in gas.

Bullard snapped the ignition switch on. “Contact.”

The mechanic yanked the propeller down as hard as he could. The engine coughed and roared to life. Bullard pulled back on the gas control for full gas.

Okay, Bullard thought, how hard can this be? His Penguin picked up speed, lifted its tail and zig-zagged down the airfield at 50 miles per hour. Almost immediately, he found himself swerving to the right. He pressed his foot too hard on the left rudder pedal. Then he found himself swerving to the left. He pressed on the right pedal. Without warning, he started whirling in circles as if the plane was chasing its own tail. Each time Bullard completed a circle, he could see the pilots near the hangars waving their arms and laughing.

Bullard wasn’t the only student pilot having problems. The other Penguin pilots were darting about and spinning in circles. One Penguin tipped over on its nose, leaving the student pilot hanging upside down in its cockpit. By late morning, gusty winds stopped the practice. A bit embarrassed, Bullard crawled out of his cockpit to laughter and good-natured ribbing from the spectators.

After a few days, Bullard mastered his straight-line taxiing technique and graduated into phase two, the rolling class.

The second part of his instruction was flying another Blériot called a Roleur. It had full-length wings and could fly, but Bullard was strictly instructed not to lift off the ground. He had to taxi back and forth on the field to get the feel of the controls, and he had to practice for three straight weeks until he got it right.

Finally, the day came when Bullard was allowed to fly. Using the same Roleur, he was instructed to lift off the ground about three feet and fly a short distance. Then he had to shut off the engine and land the plane. He repeated that exercise over and over until his instructor said he could fly at 500 feet, but in a straight line. The only turn allowed was the one when he had to return to the airfield.

Bullard roared down the field and felt the air lift the plane. He pulled back on the joystick and kept climbing until he leveled off at 500 feet. Only then did he dare a glance at the fields and trees passing below him. I’m a real pilot now, he thought. The engine droned on. He smelled the haze of castor-oil-based engine oil and felt the cold wind against his face. He was too busy to do more than glance at the countryside below him. All too soon, he had to turn and head for home.

He swung his joystick to the left and pressed his rudder pedal. His Blériot turned left and pitched upward a bit before Bullard compensated. By now, he also knew that if he had turned right, the plane had a tendency to pitch downward—a result of its rotary engine torque.

Before the day of his final test, he had to perform a series of aerial maneuvers at 2,000 feet, shut off the engine and then glide with power off to a predetermined landing spot. Graduation day arrived. Bullard was a little nervous, particularly with all the instructions coming at him from his monitor: do this, don’t do this, and when you come back, fly over the field twice, push on the joystick to come down, and cut the engine before you land.

Bullard did what he was told and headed back for the airfield. He circled it twice and realized he was confused. Did you push the joystick first and then cut the engine or was it the other way around? He circled the field again. So many instructions were swirling in his head, they were nothing but a muddled mess. He couldn’t make up his mind what to do. He circled again. For almost an hour he circled the field until he ran out of fuel.

Well, at least that solved my problem, he thought. He glided to a landing, bounced a few times on the grass field, and came to a stop.

His flight instructor and aircrew ran across the field to greet Bullard as he clambered out of the cockpit.

“Congratulations,” the instructor said, shaking Bullard’s hand. “I don’t know why you kept circling the field, but you passed the test.”

Bullard’s knees felt weak. He had made it.

On May 5, 1917, Eugene Bullard was awarded military pilot certificate #6950. He was now a pilot. After wings were pinned to his uniform, he was given a six-day leave in Paris.

Perfect, Bullard thought. I have some unfinished business there.

Settling a Bet

Bullard arrived in Paris with his pilot’s certificate in his pocket and knocked on Möise Kisling’s studio door.

“Why, it’s Eugene!” Kisling exclaimed. “What are you doing here?”

With a smile, Bullard reached into his pocket, took out his pilot’s certificate and unfolded it in front of his friend’s face.

“Why, you old devil . . .” Kisling grabbed Bullard’s hand and vigorously shook it. “Congratulations. Come in. I must tell Gilbert.”

Bullard found a chair and sat down while Kisling phoned Gilbert White.

“Hello, Gilbert,” Kisling said loudly. “Guess who’s in town and guess who’s got his pilot’s certificate.”

Bullard strained to hear the rest of the conversation, which went on animatedly for some time. He knew something was up.

Kisling finally hung up. “Eugene, we’re going to Henri’s Bar tomorrow for lunch with Gilbert. Gilbert also invited Jeff Dickson, who bet against you. He doesn’t know you’re in town.” Kisling rubbed his hands together gleefully. “This is going to be fun.”

The next day, Kisling and Bullard met White at Henri’s a little early, and the three found a table before Dickson showed up. Bullard was resplendent in tan boots laced up to his knees and wearing a blue pilot’s uniform with large, aviator wings sewn on his collar.

White drummed his fingers on the table while the trio waited for Dickson. Finally, a silhouette appeared in the bar’s front door and strode toward them.

“Hello—” Dickson said. He gasped when he saw Bullard and his uniform. After his initial shock, he managed to say, “Well, I’ll be. How in the world did you do it, Eugene?”

“I asked the French government to give me a chance, and here I am,” replied Bullard.

“Well, I’ve obviously lost the bet.” Dickson stuck out his hand to Bullard. “I hate to lose that kind of money, but I’m glad the first colored military pilot is you.”

Bullard was suddenly rich—$2,000 rich—for the first time in his life. “Thanks. For once, let me pay for our lunch. And let’s celebrate today. It’s on me.”

The foursome made the rounds of bars up and down the nearby streets, celebrating Bullard’s achievement. By midnight, it seemed that most of Paris knew that a black American had become a military pilot.

During his six-day leave, Bullard got up the courage to write to his father for the first time since he left home more than 10 years earlier. In his letter, Bullard asked for forgiveness for running away. He said he thought of his father daily. He described his life in boxing, how he won many medals fighting in the French Foreign Legion, and how he was now the first black military pilot in the world.

Weeks later, Bullard received a reply from his father, who said he regarded Bullard as his number one son and that he had forgiven him for running away.

Bullard read the letter over and over. Finally, he put it back in its envelope and smiled. My father’s proud of me. I wish he could see me now.

Advanced Training

Even though Bullard had earned his wings, he was still not qualified for combat flying. To hone his skills, he was transferred to an advanced flying school at Châteauroux, where he learned to fly some of the most advanced planes available.

A Caudron, one of the many planes Bullard flew.

First, Bullard mastered the French Caudron G-3 biplane, with its twin tailbooms and open framework fuselage. Originally flown as an observation aircraft, it was a tough and reliable little plane. But its single 80-horsepower rotary engine gave it a lackluster performance of only 68 miles per hour maximum speed. Built from wood, canvas and wire, the fragile-looking planes were jokingly called “chicken coops” by the pilots. Because G-3s were usually unarmed and vulnerable near the front lines, they were retired from combat in 1916 and then used as trainers by the French.

Next, Bullard stepped up to training in the Caudron G-4, a French biplane with twin 80-horsepower engines giving it a maximum speed of 77 miles per hour. The G-4 was derived from the G-3, but had longer wings, an additional seat for an observer-gunner in the front and four rudders instead of two. Armed with one machine gun and carrying up to 250 pounds of bombs, G-4s were flown by the French on reconnaissance or bombing missions over Germany.

Bullard had to work hard for his G-4 certification. He discovered that having two engines meant more than twice the work and skill level to fly it. But eventually he more or less mastered flying the larger plane. It was obvious, though, that Bullard was meant to fly the smaller, single-engine fighter planes.

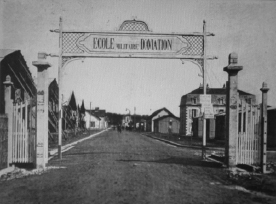

At the end of June, Bullard transferred to the Avord School of Military Aviation for his final training before combat. One of the largest aviation schools in France, the Avord School had a three-mile long and half-mile wide grass airstrip with clusters of hangars that held hundreds of planes. A number of wooden barracks with red tile roofs accommodated offices, mess halls, and sleeping quarters for the pilots and instructors.

Bullard’s flight instructors informed him that his duties would involve driving away enemy planes and escorting bombers and reconnaissance planes. He would also patrol the skies, looking for enemy aircraft to engage in combat.

The gates to the Avord School of Aviation, one of the largest in France, where Bullard learned how to fly.

Flying the latest types of planes, Bullard had to practice the intricacies of what he called “fancy flying.” His aerobatic instructors showed him how to execute changes of direction, perform rolls and corkscrews and how to attack out of the sun to prevent being seen by the enemy. He learned power dives for attacking from above or escaping attack from behind and how to pull up safely before he hit the ground. These were all necessary maneuvers for air combat, and they were maneuvers that might save his life one day.

Early combat planes had machine guns mounted on the top wing, so the bullets wouldn’t hit the propeller. Wing-mounted guns meant the pilots had to reach up to fire them—not an easy task when flying violent maneuvers during air combat and trying to aim at enemy aircraft. But Bullard practiced firing the newest synchronized machine guns that could fire through the plane’s whirling propeller blades without hitting them. Finally, he learned how to fly and fight in formation.

One day, on the ground, Bullard watched in horror as a plane buzzing overhead went into a dive and then struggled to pull up. As the plane neared the ground, its engine noise got louder and louder, and it was obvious that the plane was going to smash into one of the airfield buildings.

The plane crashed through the metal roof of the camp’s bakery with a loud bang. A white cloud rose into the air. Luckily, no fire erupted. Bullard and a crowd of other pilots ran toward the bakery, expecting the worst. White-shirted bakers ran outside, cursing loudly.

As Bullard arrived at the crash, a flour-covered pilot crawled out of the crumpled wreckage and climbed down to the ground, apparently uninjured. A stunned crowd gathered around the pilot, who was covered from head-to-toe in white flour. Captain Boucher arrived and demanded to know what had happened.

The hapless pilot stepped forward, stood at attention and snapped a salute, a puff of flour wafting from his sleeve. “It was I, mon capitaine.”

The crowd erupted in laughter. The captain shook his head in disbelief. It wasn’t the first time this pilot had crashed. But now there would also be a bread shortage for a while.

Bullard knew he was supposed to receive additional combat flying training, but instead he was placed in charge of his sleeping quarters at Avord. What a strange order, Bullard thought. But he felt it wouldn’t be long before he was sent to the front.

His sleeping quarters were shared by 22 other American pilots who had also volunteered to fly for the French. Bullard had gotten friendly with all the pilots—especially a tall American named Reginald Sinclaire, who slept only inches away in the next bunk. Bullard appointed Sinclaire his assistant and, together, they kept the American quarters spotless. The inspecting lieutenant announced they had the best-looking room in the barrack.

Eventually, Bullard started noticing that pilots who had arrived after him were shipped off to the front for combat. He was ready, too. And he was itching to go. What was the holdup? Rumors started trickling back to Bullard that an influential American in Paris disapproved of having a black pilot in the flying corps. After several weeks of being left behind by many of his comrades, Bullard started putting two and two together.

Bullard knew that Dr. Edmund Gros, an American doctor and commissioned major in Paris, had been instrumental in forming the Lafayette Escadrille. Dr. Gros was also the vice-president of a committee that oversaw the affairs of all the American pilots flying for France. Once a month, Dr. Gros would dole out 50 francs—donated by wealthy Americans—to every American pilot. But Bullard wasn’t even aware of the arrangement until another pilot happened to mention it to him.

From then on, Bullard showed up every month at Dr. Gros’s townhouse in Paris on the Avenue du Bois de Boulogne to receive his check. And every month, no matter how early he showed up, Bullard would be the last pilot to collect his check—withheld until the banks had closed and he couldn’t cash it.

Dr. Edmund Gros, an American doctor and commissioned major living in Paris, was instrumental in forming the Lafayette Escadrille. He also made life difficult for Bullard.

Bullard’s pilot friend, Edmond Genet, finally took him aside and convinced him that someone really was working against him. Bullard then approached his commanding officer: “Captain Boucher, I wish permission to write to Colonel Girard.”

Captain Boucher looked annoyed. “For what reason, corporal?”

“I want to ask why I’m being kept at Avord while France needs pilots at the front.”

“Permission denied.” Captain Boucher waved his hand. “You’re dismissed.”

Bullard simmered. It was August 5, 1917—almost three months after he received his flying diploma—and he still hadn’t been sent to fight the Germans. No doubt it was because of Dr. Gros. Now what?

Three days later, however, Bullard received orders to report to Le Plessis Belleville, a combat flight school and final stop before being sent to the front. He couldn’t believe it. Someone else must have heard of his plight and informed the right people.

His fellow pilots hoisted Bullard on their shoulders, danced, sang, and celebrated the good news. Over drinks at the canteen, some of the partying pilots let it slip that a certain American in Paris had done everything he could to keep Bullard from becoming a pilot because of his color.

Bullard knew they were referring to Dr. Gros, but he didn’t care about that anymore. He had won. Now he was going to fight in the air for his adopted country—France—and nobody was going to stop him.

Last Stop Before Air Combat

Bullard arrived at Le Plessis Belleville a few days later, ready to be assigned to a combat fighter squadron. The next day, after practicing maneuvers in a French Nieuport, he landed and was ordered to report to Captain Chevillard.

Bullard entered the captain’s office and saluted.

“At ease, corporal.” The captain shuffled some papers. “Your orders for deployment have been received from General Headquarters. But you have a six-day leave coming up, and I cannot tell you the details until you return.”

Six whole days in Paris!

Whenever Bullard was in Paris, he discovered that he never had to pay for meals or drinks. The local citizens believed it was their duty to treat soldiers headed for the front. After looking up some old friends, he met a Parisian girl with a most unusual pet—a rhesus monkey. Bullard fondly remembered working with a capuchin monkey. The girl needed money, so Bullard convinced her to sell the monkey to him. Other pilots had mascots, such as dogs and even lion cubs. Why not a monkey? Bullard handed over a few francs and immediately had a small brown monkey sitting on his shoulder.

“I’m going to call him Jimmy,” Bullard said to the girl. “Wait till my flying buddies see him.”

Bullard was right. Upon his return to Le Plessis, the other pilots greeted Bullard and Jimmy with whoops of delight. Jimmy held on tightly to Bullard and chattered back with wide eyes at the pilots. But Jimmy soon felt comfortable with all the excitement swirling around him. From that day on, Bullard carried Jimmy in his flight jacket for good luck.

Bullard was not the only one flying high in the sky. Jimmy, his pet monkey, often accompanied him on flights.

Tacked up on the bulletin board was a list of new assignments. Bullard ran his finger down the list and gasped. He had been assigned to Squadron Spa-93, one of the top escadrilles that flew French-built SPADs, some of the best fighter biplanes in the war. He bubbled with pride and hoped he could live up to the escadrille’s famous reputation.

Bullard arrived at Spa-93’s landing strips near the village of Beau-Zie-sur-Aire, not far from Verdun. He spent a week meeting his two new mechanics and practicing landings and aerial combat maneuvers in a SPAD VII.

The rugged SPAD was fast. Its Hispano-Suiza 150-horsepower inline engine gave it a top speed of 120 miles per hour during level flight. During a dive it could go as fast as 250 miles per hour. Equipped with a Vickers .303 caliber synchronized machine gun that fired through the propeller, it was a deadly fighting machine. But it was also dangerous for pilots who didn’t learn its idiosyncrasies. The SPAD didn’t glide well. And it was difficult to maneuver at low speeds. Even more dangerously, its thin wings gave it a very sharp stall without much warning at slow speeds. As a consequence, it was a difficult plane to land safely and not crash.

At the end of the first week in September, 1917, Commandant Ménard called Bullard into his office. “Corporal Eugene Bullard, do you consider yourself ready for combat?”

Bullard knew he was. “Yes, sir, I am quite ready.”

“Very good,” the reply came. “Your flight schedule is posted. You are going up tomorrow on a patrol. Don’t get out of formation to do battle until you have a few hours of experience under your belt.” The commandant smiled at Bullard. “We don’t want Jimmy to become an orphan.”

Before turning in for the night, Bullard placed Jimmy in a wooden cage and covered it with a sheet. Then he headed for the mess hall and read the orders for the next day. He was one of 14 pilots scheduled to fly from 8–10 a.m. and from 4–6 p.m.

Bullard was ready. He just hoped he could sleep that night.

First Combat Flight

It was still dark when Bullard woke to the sound of a blaring horn calling the morning assembly. He quickly got into his fur-lined flying gear, laced up his boots, and picked up the chattering Jimmy from his cage. After grabbing his flying helmet and his customary French breakfast—a large cup of coffee—he stepped into the cold, predawn blackness and headed toward the flight line with Jimmy on his shoulder.

Except for an occasional artillery shell exploding miles away, the morning was quiet. As he got closer to the flight line, he could hear the soft footsteps of the other pilots approaching.

Bullard felt real fear. Soon, he would be climbing into his airplane and flying over the front. The eyes of the world are watching me, he thought. I have to do or die, and I don’t want to die.

The SPADs were lined up wingtip-to-wingtip in two straight rows outside the hangars. A few minutes later, all the members of the patrol were gathered together near their assigned planes waiting for instructions.

Commander Ménard spoke up. “Rendevous with Captain Pisard at 6,000 feet. And take good care of Bullard. We don’t want Jimmy left without a father.”

All the men laughed, including Bullard.

“Now, up into the air, men,” the commander ordered. “Quickly.”

Each pilot dashed for his plane. Bullard climbed into his cockpit and fastened his helmet. Jimmy jumped to the floor and tugged on Bullard’s pants—a signal that he was ready to climb inside Bullard’s fur-lined jacket.

“Okay, Jimmy,” Bullard said, picking him up. “In you go.”

One of Bullard’s mechanics yelled, “Switch off!”

“Switch off,” Bullard replied.

The mechanic slowly turned over the propeller and stood back. “Contact!”

“Contact.”

The mechanic reached up and quickly flipped the propeller blade toward the ground. Puffs of smoke shot out the SPAD’s exhaust pipes. The engine sputtered to life. Bullard let it warm up while he checked his machine gun. A mechanic hopped on the lower wing and wiped the windshield and fastened Bullard’s seatbelt; another held a rope ready to jerk out wooden chocks holding back the plane.

A signal. A salute from Bullard. The chocks were snatched away and his SPAD trundled to the airstrip. He gave it full throttle and raced down the field into the wind, the eager plane lifting off almost immediately.

Bullard climbed to 6,000 feet, leveled off and quickly found his place in the V-formation of 14 SPADs and Nieuports. Captain Pisard’s plane led the way at the point of the “V.” Six planes each—only a few feet apart—formed both legs of the “V,” and one trailed behind, in the middle of the formation. For the first half hour, they flew back and forth on the French side of the line, always keeping a sharp lookout for the enemy.

In the hazy distance, Bullard could make out observation balloons floating above both sides. Farther still, Bullard saw a few circling enemy planes miles behind the German lines.

Keeping one eye on Captain Pisard for any signals, Bullard constantly swiveled his head—looking up, looking down, looking everywhere—for German aircraft. He wished he had another set of eyes.

Captain Pisard motioned for the formation to follow. He banked his plane and headed across the lines. This is the real thing, Bullard thought, with a sudden thrill. The formation dutifully followed behind its leader. Occasionally, Bullard would see bursts of ugly, gray smoke appear nearby in the sky. These were explosions from anti-aircraft artillery firing at them—what the British nicknamed “Archie.” Luckily, Archie did not do any damage.

Anti-aircraft guns tried to shoot planes from the sky.

After flying miles into German territory to the city of Metz, the captain signaled for his men to return to the French side. Bullard looked down as he flew over Verdun. He saw the trenches and the fighting still raging below. He remembered standing in those same muddy trenches and looking up at the airplanes flying overhead. Now, he was the pilot flying over the foot soldiers.

Without warning, the captain’s plane suddenly banked to one side. The other planes instantly fell out of formation and scattered across the sky. Bullard’s heart skipped a beat. It’s an attack! He instinctively slipped out of formation, not wanting to be a target. He looked about wildly, his heart pounding, but he couldn’t see any German planes. Where are they?

After a minute or so of everyone flying battle maneuvers, the captain flew past Bullard. The captain signaled for the pilots to form up again and fly back to home base. Bullard felt his arms quivering from the excitement. What in the world was that all about?

Bullard landed safely and taxied to his tie-down spot. After climbing out of his cockpit, Bullard was surrounded by the other pilots who slapped him on his back and stuck out their hands to congratulate him. There were no enemy planes. There was no air battle. It was only an initiation rite they always performed for the benefit of any new pilot. Everyone laughed. Bullard laughed, too. He was one of them now.

“Go take a rest,” the pilots advised Bullard. “You have to fly again at four o’clock.” Bullard felt revved up and not particularly tired. But after the 11 o’clock meal, he headed for his bunk and stretched out, still wearing his flying suit.

Sleep came instantly.

Blooded

September 1917. Bullard awoke with a start.

The duty sergeant was still shaking his shoulder. “It’s 3:30. Time to get up, Bullard.”

Bullard swung his body upright and rubbed his eyes. He stood up and stretched with an enormous yawn. He grabbed his helmet and let Jimmy out of his cage. The monkey clambered up on Bullard’s shoulder and held on while Bullard headed toward the flight line.

Commander Victor Ménard stood next to his SPAD, waiting while the pilots approached. After the commander’s men were gathered, he joked about Bullard’s monkey. “Bullard, do you think your son will protect us today?”

The pilots laughed. Bullard’s tension lessened a bit.

After a few minutes, the French SPADs and Nieuports had formed the now-familiar V-formation and were climbing through the cool air to 6,000 feet. Ménard signaled them to head for the front in the Verdun sector, a particularly dangerous area.

It wasn’t long before Bullard spied a number of moving dots in the far distance. As the dots grew larger, it became obvious the dots were four large German bombers surrounded by 16 German fighter planes—Fokker triplanes—headed in the direction of Bar-le-Duc.

Ménard signaled for his fighters to prepare for combat and divide into two formations of seven planes each.

In an instant, the German triplanes dove toward the French. Planes flashed by Bullard in a kaleidoscopic whirl of aerobatics, punctuated by rat-tat-tats and the whiz of bullets whipping past. Bullard yanked his joystick about, maneuvering to avoid the attackers. He glimpsed smoke trailing from one bomber—then from two German fighters, each plunging to earth.

Bullard maneuvered behind one Fokker that was desperately trying to shake Bullard’s sky-blue SPAD. Bullard kept on his tail and managed to fire several bursts. Before Bullard could tell if he had even hit the plane, a stream of bullets slashed through the air over his cockpit.

Bullard whipped his plane into a twisting dive, then rose up to shoot at another plane that appeared in front of him. Bullard’s heart pounded in rhythm with the rattle of his machine gun as it fired. The enemy plane jerked about and spun out of range.

Bullard glimpsed a damaged bomber banking to return to the German lines—an arc of gray smoke trailing it. A German fighter flashed in front of Bullard, blotting out his view of the bomber for an instant. In the distance, the bomber reappeared, erupted in a stupendous ball of flame and tumbled to earth in pieces.

Another Fokker flew by Bullard. Instinctively, he aimed his SPAD at the German plane and squeezed off some more rounds. In the distance, Bullard spied the other three bombers corkscrewing to earth, two of them on fire.

It was all over in just a couple of minutes. The German Fokkers disengaged and turned home. As the French planes headed back to their base, Bullard replayed the violent combat that he had just experienced. Everything had happened so fast. He noticed his hands were gripping the joystick tighter than usual. He ordered his hands to relax. His pounding heart settled down.

He felt Jimmy stirring in his flight jacket. “We made it, Jimmy.” He stroked the monkey’s head. “You’re my good luck.”

After safely landing, Bullard and the pilots quietly assembled in the camp’s bar, awaiting the official reports. Two of their men had been shot down, it was announced. There was so much action going on, Bullard hadn’t even noticed at the time.

The mechanics read their reports. Bullard’s mechanic stated that Bullard’s SPAD had fired 78 rounds and received seven bullet holes in its tail section. A sudden chill passed through Bullard. Close!

Commander Ménard approached Bullard. “Well done, Bullard,” he said. “Now, you have been blooded with your first combat.”

Most of the pilots headed for the mess hall, lost in thought about their fallen comrades. Bullard didn’t feel much like talking as he followed the other pilots. On the mess hall bulletin board, he noticed his patrols the next day: 7–9 a.m. and 1–3 p.m. Bullard slowly picked at his tasteless meal.

Bullard never missed a flight patrol unless the weather grounded the planes. With each flight, his jitters lessened, and he grew more confident. He soon became an old-timer and part of a fierce fighting team. The other pilots felt safe flying with Bullard because they knew he was a good pilot. They knew he wouldn’t run from a fight. And they knew he was itching to shoot down a German plane.

After six days of combat flying, Bullard was transferred on September 13 from Spa-93 to Spa-85, another crack squadron in the Lafayette Flying Corps. Spa-85 patrolled the Verdun sector in the region of Vadalaincourt and Bar-le-Duc.

One day, Bullard was patrolling his sector with his squadron near the German lines when a particularly aggressive formation of German Fokker triplanes appeared. Bullard didn’t realize at the time the red-painted planes were part of the Richthofen Flying Circus—led by Baron von Richthofen—known as the most dangerous enemy pilot in the war. But Bullard could tell they were looking for a fight, and they were headed straight at him.

Bullard patted Jimmy inside his flying suit. “Here they come,” he whispered. He armed his machine gun and gave his SPAD full throttle.

Shot Down

The menacing red Fokkers flew straight at the French squadron, obviously looking for a fight. Bullard watched the lead plane for his signal. The captain motioned for combat maneuvers. The formation of French SPADs and Nieuports spun apart in wild gyrations, ready for battle.

The sky quickly swarmed with airplanes, each one trying to maneuver an enemy machine into its crosshairs. Bullard realized a triplane was headed directly at him, with staccato flashes of light and smoke erupting from its machine guns. Rivers of tracer bullets screamed past Bullard’s SPAD.

Bullard mashed his right rudder pedal and heaved his stick to corkscrew down out of range. His agile plane instantly responded, pressing Bullard down in his seat. The taut reinforcing wires on his wings sang a higher pitch as he raced toward the earth.

Then, pulling up from below, Bullard fastened himself behind another Fokker. He fired short bursts from his Vickers machine gun. The Fokker wagged across the sky, trying to shake Bullard, but he stuck like a burr—firing bursts whenever the red plane swung across his crosshairs.

A short stream of bullets from Bullard’s gun punched a line of holes across the Fokker’s wings and fuselage. Pieces of wing fabric tore into strips and fluttered in the slipstream. The Fokker’s engine belched smoke, then started puttering and backfiring. The Fokker pilot made a slow, desperate turn away from the air battle. The plane began losing altitude. Bullard followed the crippled plane over the German lines to finish it off with another burst. He lined up the Fokker in his crosshairs. My first kill. I can’t miss—

Bullard fired at the Fokker. Criss-crossing pencil lines of whitish smoke from tracer bullets streaked near Bullard’s SPAD. German machine-gun crews on the ground were firing at Bullard in an effort to save their pilot. As soon as Bullard realized how low and vulnerable he was, he heard bullets thwap holes in the fabric of his plane. He heard the splang of bullets hitting metal parts. The SPAD shuddered and coughed. The controls felt mushy.

Bullard knew he was in serious trouble.

In the distance, Bullard noticed the smoking Fokker falling toward the ground in German territory. But he had no time to watch. He had to worry about himself now, or he would crash behind enemy lines.

After swinging his sputtering plane around toward the French lines, Bullard coaxed and willed the plane to stay aloft until he could find a safe landing spot. He finally made it over the enemy lines, but it still seemed like every German in the war was firing at him.

The SPAD’s engine belched black smoke. Castor oil sprayed Bullard’s windshield and face. He wiped his goggles with his sleeve and desperately tried to keep his engine running. A loud knock. The engine chugged one last time and died. Bullard had to land—now. The controls felt heavy. The SPAD hurtled toward the ground.

Bullard saw a muddy field in no-man’s land appear ahead. The unnatural silence was broken only by the wind shrieking past the SPAD as it rapidly lost altitude. Bullard pushed away the cold fear that he wouldn’t make the field. Shell-shattered trees passed ever closer beneath him. Bullard tore off his goggles; they might shatter on impact. He focused on the edge of the field. The ground came up fast. Then holding his breath, he carefully pulled back on his stick. Keep enough airspeed. Don’t stall. Don’t stall. Keep the wings level. Don’t hit a shellhole.

The SPAD flared out a few feet above the ground and glided for a short distance. Its wheels thumped down. The plane bounced a few times. Its tail settled as it lost speed, and it finally came to rest. Bullard exhaled. At least I didn’t flip over. He reached inside his jacket and stroked Jimmy’s head. “You gave me good luck once more.”

Bullets whizzed around the downed SPAD. Bullard quickly unfastened his seatbelt, clambered over the far side of his fuselage, and fell into a muddy shellhole. As long as the Germans were firing at him, he could only lie in the cold mud and listen to bullets puncturing his plane.

Hours dragged by. He shivered in his soaking wet clothes. Bullard felt Jimmy shivering, too. As darkness settled over no-man’s land, the constant sniping at Bullard finally ended. Without warning, voices emerged from the remains of a forest behind him. Bullard whirled around. With a sigh of relief, he realized they were speaking French.

“Ah, Monsieur Bullard, I see you are still alive. And how is your son?” It was Bullard’s aircraft mechanic. “We are here to transport you and your pathetic airplane back for repair.”

A group of mechanics and soldiers with some horses appeared out of the shadows. The men tied Bullard’s plane to a couple of horses and dragged it out of sight of the Germans. The mechanics quickly removed the SPAD’s wings and set them aside. They lifted the fuselage onto a horse-drawn transport wagon, loaded the wings and tied everything down. Bullard and the mechanics hopped onto the back of a truck. They headed for the airfield a few miles away.

“I counted 96 holes in your machine, Bullard,” Bullard’s mechanic said. “None in you. You’re a lucky man.”

Bullard stroked Jimmy’s head.

A Confirmed Kill

Bullard’s life settled into a routine. If the weather was cooperative, he would fly a combat mission in the morning and another in the afternoon. But now it was a morning in November 1917—wintry cold and thick with clouds. Bullard thought he wouldn’t be able to fly that day, so he rolled over in his warm cot and promptly fell back asleep.

All too soon, the duty sergeant shook him awake. “Get up, Bullard. You fly at 11.”

Bullard wearily rose and stretched. Outside, the clouds were breaking up, allowing patches of blue sky to show through. He hurriedly dressed in his warmest flying gear and peeked into Jimmy’s cage. Jimmy had been unusually quiet the last few days. He looked like he wasn’t feeling well.

“I guess you can’t go with me today, Jimmy,” Bullard said. “But I’ll be back soon. You get well.”

In a few minutes, Bullard had fired up his SPAD, ready to do battle again with the Germans. At a signal the squadron roared down the airfield and launched themselves toward the Verdun battlefields.

At 12,000 feet, Bullard settled into the V-formation with his fellow pilots. As the planes droned toward the lines, they flew through puffy clouds dotting the sky. Bullard kept a sharp eye out for enemy planes. He was itching to do battle again. He was certain that he had shot down the red Fokker. But he didn’t get a confirmed kill for it because the plane had crashed behind German lines, and no one else had seen him do it.

The air was rough. Bullard’s plane bounced up and down as he threaded his way through clouds that constantly interrupted his view of the formation. He knew enemy planes could be hiding anywhere. He kept a constant lookout in all directions. Bullard patted his flight jacket. It sure feels funny without Jimmy. I hope he doesn’t have anything serious. He’s been good luck so far.

Bullard confronted a particularly large cloud and skirted around it. When he reached the other side, he suddenly realized he was alone in the sky. Where are my wingmen? He looked below and saw that he had crossed the Verdun battlefields. Bullard shivered. It’s really freezing today. Where is everyone? The sound of the wind whooshing around his windshield and the constant roar of his engine made him feel even more alone. Where are they?

Finally, in the distance Bullard spotted a V-formation of seven planes. His heart leaped. There they are! No . . . they’re flying in the wrong direction. They’re Germans! The formation of Pfalz scout planes was flying 3,000 feet below him toward French-occupied territory. Thoughts of being alone instantly evaporated. Hope of a confirmed kill filled Bullard’s mind.

The German formation kept flying straight and didn’t make any unusual maneuvers. Maybe they haven’t seen me. Or maybe it’s a trap. Bullard scanned the sky in all directions. No other planes.

Bullard slipped into a large cloud to hide. White mist enveloped him, and rivulets of water streaked over his wings and fuselage. When he emerged, the Pfalzes had flown past him. As far as he could tell, they still hadn’t seen him. Wary of a trap, Bullard took one more cautious look around before he pulled his throttle and shoved his stick forward.

Bullard’s SPAD dove behind the last Pfalz in the German formation. Bullard triggered a burst of bullets from his Vickers—rat-tat-tat. The Pfalz pilot twisted around as a stream of tracers streaked past him. He looked startled to see Bullard’s blue plane streaking toward him, with its machine gun blazing. The Pfalz swooped up in a loop to get behind Bullard.

Bullard threw his plane in a diving right bank and aimed for a nearby cloud to hide. The Pfalz completed its loop. The pilot must have expected to find a SPAD in front of him, but Bullard’s plane was nowhere to be seen.

Emerging from his hiding place, Bullard saw the Pfalz above him. He shoved in his throttle and raced toward the enemy plane. As Bullard neared the Pfalz, he noted the black cross on the right side of its fuselage. The Pfalz centered in Bullard’s gunsight. The German pilot saw the SPAD too late.

Bullard squeezed the trigger on his Vickers. He let off a long burst—rat-tat-tat-tat—and saw a line of holes march across the enemy plane toward the cockpit. The German pilot jerked as the bullets found his body. The Pfalz pitched up, did a slow roll to one side and fell toward the earth in a long spiral.

The deadly aerial duel took only a few moments. Before the other Pfalzes could engage Bullard in combat, he made a sharp bank and sped toward some large clouds. With his heart thumping, Bullard hid as long as he could. When he felt it was safe, he emerged and headed straight for home, still looking for his comrades.

There shouldn’t be any doubt about this kill, he thought. The Pfalz had crashed on French territory.

Transferring to the American Flying Corps

For most of the war, the United States had remained neutral, but after a number of ships carrying Americans had been torpedoed by German submarines, diplomatic relations were broken off with Germany. Then, on April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. The first American troops arrived in France on June 26, 1917.

When Bullard heard that the Americans were coming to fight in France, he wondered if he would be able to transfer from the French Flying Service to the American Flying Service. Finally, in October, he heard that all American pilots flying for France would be accepted into the American Flying Service and promoted to the rank of lieutenant.

Bullard immediately went to Commandant Ménard’s office, stood at attention, and snapped off a salute. “Permission to transfer to the American Flying Service, sir.”

Ménard returned the salute. “At ease, Bullard.” He shuffled through some papers and grabbed one. “Ah, here we are.” He cleared his throat. “Colonel Raynal Bolling, the commander-in-chief of the American Flying Service, has created a board to examine and approve the transfer of American pilots who fly for France.” He looked at Bullard. “But it says you need to pass a physical.” With a grin, he asked, “Do you think you think you can pass a physical?”

Bullard grinned back. “Yes, sir.”

“Well, then, you have my permission—and my blessing. France will miss you.” Ménard waved Bullard away. “I wish you well.”

Flying conditions were poor in early October. Bullard used the opportunity to hop on a train to Paris to take his flying physical with other American pilots. Even though he had been poorly treated in his home country, he was still proud to be an American. He daydreamed about becoming a lieutenant—an officer—wearing an American aviator’s uniform and fighting for his country as an American combat pilot.

After arriving in Paris, the pilots were examined by young American doctors in uniform. When it was Bullard’s turn, he entered the examining room and saw four doctors busy reading his records on the table in front of them. He also noticed Dr. Gros, who didn’t look particularly happy to see Bullard.

Bullard stood until one of the doctors looked up and asked, incredulously, “How did you ever learn to fly?”

What does he mean by that? Bullard wondered. He patiently explained how he had gone through pilot training with other Americans—the same training that all French military pilots had gone through to earn their wings. Bullard reminded the doctors that he received a flying certificate the previous May.

The doctors mumbled among themselves. One doctor rose and asked Bullard to sit on an exam stool. “Take off your boots,” he ordered. He held Bullard’s feet and closely examined them, flexing his ankles side-to-side. “Hmmm,” he said. “You have flat feet.”

“I served in the infantry and walked all over France,” Bullard retorted. “No officer ever found my feet too flat to do that. Besides, I’m a pilot now, and I don’t fly with my feet.”

“I suppose you’re right. Okay, open your mouth.” The doctor pressed Bullard’s tongue down with a tongue depressor and peered into his mouth. “Say ‘ahhh.’”

“Ahhhh.”

“Hmmm, it appears you have enlarged tonsils.”

“Well, lucky for me, I’m not an opera singer,” Bullard said. “You can see in my records I have never lost a day of duty because of a sore throat.”

“Once again, I guess you’re right,” the doctor replied. “Next, we’ll do a color-blindness test.”

In the back of the room, Bullard heard Dr. Gros clear his throat and shuffle the papers in Bullard’s file.

The young doctor interrupted Bullard’s thoughts. “Here are some pictures of dots with colored numbers in them.” He held a book in front of Bullard and flipped through the pages while Bullard correctly named all the numbers.

After a few more tests, the doctors announced that Bullard had passed the examination for becoming an American pilot. They would get in touch with Bullard when the necessary paperwork was processed.

Bullard was thrilled. As he headed back to the Spa-85 airfield with the other pilots, Bullard wondered how long it would be before he would be flying for his own country.

Bullard Receives His Orders

Unknown to Bullard, Colonel Bolling of the American Air Corps sent a message to the French Flying Service on October 21, 1917. The message ranked the 29 American pilots who had taken the physical examination and named those who had been approved for transfer whenever it was convenient for the French military.

Meanwhile, Bullard kept flying combat missions and saying goodbyes to his fellow pilots who, one-by-one, were called into Commandant Ménard’s office over the next several days and given their American transfer papers.

At first, Bullard thought it would be only a matter of time before he was transferred, but it slowly began to dawn on him that all the transfers were given to white pilots. Still, his experience gave him an edge, he thought, and he did pass the physical exam.

Finally, in early November, Bullard was called to Ménard’s office.

“At ease, Bullard,” the commandant said. He held up a paper. “Bullard, here is a list of 29 pilots who have been graded by the Americans for transfer into their air corps. Only one pilot was rejected.”

Bullard gasped.

“It wasn’t you, Bullard. You did pass, but you ranked 28th out of 29—dead last for those who were accepted.”

Bullard felt a sense of relief wash over him.

Ménard looked down at the paper. “Unfortunately, to fly for the Americans, you must be an officer.” He frowned. “The others were promoted to lieutenant, but you were promoted only to sergeant.” Ménard hesitated. “That means your transfer is denied. There is nothing I can do.”

Bullard’s knees felt weak as he left the office. Insulted and hurt by his own country rejecting him, Bullard tried to keep up his spirit by rationalizing that he was at least fighting on the same front as the American soldiers. In a way, he thought, he was doing his duty and serving the United States.

The weather turned bad again, so Bullard asked for a 24-hour leave with his mechanic to visit his friends, Kisling and White, in Paris. At the end of the Paris visit, the pair traveled to Bar-le-Duc and checked into the Café du Commerce. The small inn was near where they could catch the first morning train back to their airfield.

Bullard and one of his friends headed downstairs to the inn’s restaurant for a cup of coffee and brandy. Being the only black person made Bullard stand out in the room crowded with soldiers. He elicited some curious looks, but he was used to that. One soldier, a captain, motioned for Bullard to come over and speak with him.

“Do you know that officer?” Bullard asked his companion.

“No. I’ve never seen him, but it sure looks like he wants to talk to you.”

Bullard got up and walked over to the officer’s table, stood at attention and saluted. The captain remained seated and didn’t return the salute. Bullard knew the officer was violating military regulations, and he remained at attention.

The captain peppered Bullard with questions, but Bullard remained silent. The officer yelled at Bullard, “Why don’t you answer me?”

Bullard remained silent.

Livid with rage, the captain tried again, even louder. “Why don’t you answer me?”

Bullard replied, “I can’t answer you, sir, and I can’t consider you an officer until you return my salute.”

The captain jumped to his feet, insulting Bullard with a string of curses. He pointed at Bullard’s medals. “You are unworthy of those decorations.”

At last, a major at a nearby table who was watching the incident shouted at the captain to sit down and stop his disgusting behavior. The major took Bullard aside and explained that the captain had been commanding colonial troops in Africa and hadn’t yet adjusted to the customs in France. “Please forget what happened. I will defend you if that officer tries to cause you any more trouble.”

“It is forgotten, sir,” Bullard said and saluted.

The major returned the salute. “Thank you. We are all French soldiers. Vive la France.” He clicked his heels and strode off.

Back at the airfield, Bullard tried to forget the unpleasant evening. But four days later, he received a letter from Dr. Gros. The correspondence stated that the doctor was disappointed that Bullard had quarreled with an officer and Bullard deserved whatever punishment might fall upon him. Bullard couldn’t believe what he was reading. He lay back on his cot and wondered how in the world Dr. Gros—back in Paris—knew what had happened that night in Bar-le-Duc.

The next morning, the duty sergeant shook Bullard awake. “Bullard, the flight doctor wants to see you.”

Something was up. Bullard was sure of that.

The doctor told Bullard to sit down. “How is that leg of yours?”

“Fine,” Bullard replied.

“Bullard, in the military we must sometimes take orders. I have been ordered to have you evacuated—released from combat duty.”

Bullard was shocked. “Why?”

“I don’t know, but I suspect the orders must be revenge for something you have done.”

On November 11, 1917, Bullard was removed from the French Flying Service. He later transferred to his old unit—the 170th French Infantry. Because of his thigh wound, he was declared unfit for infantry combat duty and was sent to a military camp, Fontaine du Berger, 300 miles south of Paris. He performed menial tasks in a service battalion until the end of the war. To make matters worse, Bullard’s Jimmy died during the great flu epidemic that swept the world in March 1918 and killed millions of people.

The Great War, as people called it, finally ended on November 11, 1918. More than 8 million soldiers and 6 million civilians had been killed. And 21 million soldiers had been wounded. Bullard was eventually demobilized from the military and headed for Paris.

He was about to start a new life.