6

Between the Wars

Paris

By the spring of 1919, Bullard was living in Paris and looking for a job. He began training as a boxer again, thinking that he might have a comeback in the ring—in spite of his head and thigh wounds from the war.

While training, Bullard kept his eyes open for other ways to make a living. He worked as a masseuse and an exercise trainer to an exclusive clientele that included many celebrities and prominent Parisians. Then he discovered that jazz bands springing up after the war were drawing large crowds at European nightclubs. When he noticed that black American jazz musicians were making good money in Paris, he decided to take lessons on playing the drums.

Bullard quickly mastered the basic techniques on drums. He was soon hired by a nightclub entrepreneur, an Italian named Joe Zelli, to play with a band in his club. By law, nightclubs had to close at midnight, but Zelli thought that if he could get an all-night license from the authorities, he could be very successful. If his club, Zelli’s, was the only one open all night, it would surely draw tourists and Parisians who had plenty of money to spend.

At first, Zelli could not get a permit. But Bullard intervened on his behalf, using his influence and knowledge of French at the license bureau. In no time, Zelli had his permit. From then on, Zelli’s opened at midnight after the other clubs had shut down for the evening and didn’t close until after breakfast. Crowds packed the nightclub every night and spent small fortunes. The staff wore tuxedoes. So did the male customers. Women wore the latest Parisian fashions. Everyone wanted to go there.

Bullard played in one of the two bands at Zelli’s. He enjoyed playing, but he still itched to fight. Zelli understood Bullard’s desire to get back into the ring. And Zelli assured Bullard that he would always had a job at the club when he returned.

Taking Zelli at his word, Bullard signed a contract for two comeback fights in Egypt. He also signed a six-month contract to play with a jazz ensemble at the Hotel Claridge—a swank hotel in Alexandria, Egypt.

On December 21, 1921, he fought his first match in Egypt, which ended in a draw. His second bout, held on April 28, 1922, was a 15-round match against an Egyptian boxer who was at least 20 pounds heavier. During the fight, Bullard severely injured his right hand. The hand swelled up like a balloon, and Bullard had to mostly use his left jab. That match also ended in a draw. But Bullard was convinced he had won, in spite of the ruling from the referee—who just happened to be the boxer’s brother-in-law.

Bullard’s injured hand never healed correctly. He hung up his boxing gloves and never fought professionally again.

After Bullard returned to Paris, he became the band leader at Zelli’s. Then he was promoted to manager and hired the entertainers who worked there. The club was a huge financial success by then. Regular customers included movie and stage stars, famous musicians, writers, politicians, and members of high-society.

One thing was lacking, though. Bullard wanted a family. During the war, his painter friends Kisling and White had introduced him to a young French girl—Marcelle Eugenie Henriette. Marcelle was from high society—the daughter of Louis Albert de Staumann and the Countess Helene Heloise Charlotte—so Bullard was surprised that he was still welcome to visit after the war.

Eventually, he asked Marcelle to go dancing. Love soon blossomed. After getting up the courage on the Fourth of July, 1922, Eugene approached Marcelle’s parents. He told them of his love for their daughter. Albert and Helene Henriette laughed. “Our daughter has felt the same way about you for a long time.”

A year later, on July 17, 1923, Eugene Bullard, age 28, married Marcelle Henriette, who was 22, at the city hall in Paris. Marcelle’s parents threw an elaborate wedding party that attracted people from all walks of life. The wedding caused a sensation—not because of the difference in the couple’s color—but because of their difference in social standing.

The Bullards honeymooned for two weeks on the southern coast of France at the fashionable resort of Biarritz, not far from Spain. The couple returned to Paris and settled in a luxurious apartment with a view of the Eiffel Tower. Eleven months later, on June 6, 1924, their first daughter—Jacqueline Jeanette Marcelle Bullard—was born. In October 1926, their only son—Eugene, Jr.—was born, but six months later he died of pneumonia. The following year, in December 1927, their second daughter—Lolita Josephine Bullard—was born.

Bullard took his family responsibility seriously and pondered how he could be a better provider.

He decided to aim for something even bigger than managing a club.

Snubs and Successes

In 1928, Bullard bought the small, triangular-shaped Le Grand Duc nightclub from its current owner, Ada Louise Smith. Known to everyone as “Bricktop,” she was a red-headed, light-skinned black singer and dancer from the south side of Chicago. Bricktop was a favorite of American songwriter Cole Porter, who helped make her one of the stars of Paris. Eventually she became world-famous.

Bullard was determined to make a success of his club. At first, many of Bullard’s musician friends played at his club for no money, just to return the favors he had given them over the years. As business picked up, Bullard hired a number of famous entertainers, making his nightclub a favorite attraction for the rich and famous. On a typical night, his patrons might include movie stars like Charlie Chaplin and Edward G. Robinson, artists like Pablo Picasso, or writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. (The black drummer in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises was likely based on Bullard.) Even Edward, the Prince of Wales, was a regular when he was in Paris. Le Grand Duc was the place to be seen.

Each year, Bullard arranged for an African American band to play a free concert during the nurses’ graduation dance at the American Hospital in Paris. He wanted to express his thanks for how well the hospital treated the local musicians and artists.

The free concerts were a big hit with the staff doctors and nurses. They all thanked Bullard profusely for his services—except for one hospital administrator. Dr. Gros—the American doctor who had engineered Bullard’s transfer and demotion from the French Flying Service—mostly ignored Bullard by pretending not to know him.

In June 1928, Bullard learned from Lt. Ted Parsons, an old flying friend, that a monument honoring the Escadrille Lafayette and the Lafayette Flying Corps had been erected in a Paris suburb not far from Versailles. The dedication ceremony was scheduled for July Fourth. Every American aviator of the corps had been invited, except Bullard.

Bullard was determined to see the ceremony, so he went anyway—invitation or not. The impressive white, stone memorial he saw was composed of a central arch upon which the names of dead American pilots were inscribed. Under the monument was a sanctuary crypt holding 68 sarcophagi, which held the remains of dead pilots.

From his vantage point, Bullard saw Dr. Gros waiting in the reviewing stand with other French officials. Dr. Gros, the president of the Board of the Memorial Association, came forward when the ceremony began and formally presented the monument to France.

The American ambassador, Myron T. Herrick, then spoke, referring to criticism about the late entrance of the United States in the war:

“During three terrible years, when the sting of criticism cut into every American soul, these pilots were showing the world how their countrymen could fight if they were only allowed the opportunity. To many of us they seemed to be the saviors of our national honor, giving the lie to current sneers upon the courage of the nation.”

After the ceremony, Bullard lined up with the other Corps members to shake hands with the officials. Dr. Gros was forced to shake Bullard’s hand, but he didn’t look happy.

Sometime later, Bullard discovered the French government had also given scrolls of gratitude to Dr. Gros for distribution to every American pilot who had flown for France during the war. Bullard was the only pilot who didn’t receive one.

It became obvious to Bullard that—in the end—Dr. Gros had once again gotten his way. Bullard made a silent vow that he would keep trying to get the scroll that rightfully belonged to him.

For now, though, he had to turn his attention to his business and his family.

Nightclubs and Spies

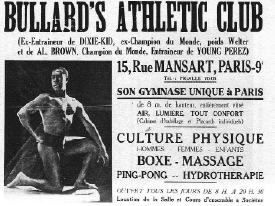

By the early 1930s, Bullard sold Le Grand Duc. He was successful enough, though, to purchase another nightclub named L’Escadrille and a gymnasium he named Bullard’s Athletic Club.

Bullard posed for muscleman-type photos that were included in advertisements for his athletic club, which listed boxing lessons, massage, whirlpool baths and even ping-pong. Catering to men, women and children, Bullard’s club attracted both Parisians and foreigners. They appreciated his style and his fluency in French. And that included Jeff Dickson, who had bet Bullard he couldn’t become a pilot. Dickson had become a boxing promoter, and he trained his boxers at Bullard’s.

Bullard eventually opened an athletic club in Paris, where he sponsored wrestling matches and other sports.

After eight years, Bullard separated from his wife. They divorced in December 1935, their differences in social status and likes and dislikes finally becoming too much for the marriage. In 1936, Bullard received custody of 12-year-old Jacqueline and 9-year-old Lolita. His daughters received the finest education and attended a private school south of Paris. All of this cost Bullard a lot of money.

Luckily, Bullard’s nightclubs hadn’t been affected very much by the Great Depression. His new L’Escadrille club was always packed with customers, making him financially secure. And his athletic club attracted many famous people, including trumpeter Louis Armstrong and pianist Fats Waller, who liked to exercise after patronizing Bullard’s nightclub.

Life seemed good for Bullard, but for a number of years the French military intelligence had been closely monitoring events in nearby Germany. Adolf Hitler had strengthened the German military and taken over Austria and Czechoslovakia by force. The French government believed that Germany once more wanted war with France.

Early in 1939, Bullard was approached by Inspector George Leplanquais. He spoke with Bullard in the nightclub office.

“Eugene,” the inspector said, shutting the office door, “you know how to speak German. Would you agree to listen in on conversations from your German customers and tell me about any suspicious activities?” Before Bullard could answer, the inspector interrupted. “Think before you answer because if you agree, you can never change your mind.”

“Before I answer you,” Bullard said, “will my daughters be safe?”

Without hesitation, Inspector Leplanquais replied, “You have my word, Bullard.”

“In that case, my answer—of course—is yes.”

“Trés bien, Bullard. You have our gratitude.”

“One thing, inspector,” Bullard said. “I’ve seen a young blonde hanging around German customers in my club. I’m beginning to think she’s a German sympathizer or maybe even a spy.”

Inspector Leplanquais chuckled. “You’re half right, Eugene. She’s a spy by the name of Cleopatre Terrier. She works for us, and you’ll be working with her.”

In a few days, Bullard was introduced to Terrier, an attractive 27-year-old Alsatian woman who was fiercely anti-German. “Call me Kitty,” she said. Fluent in German, French, and English, Terrier was working with the French to avenge her father who had been killed by the Germans in the Great War.

From then on, whenever Bullard was near a table with Germans he would listen intently but unobtrusively. At the time, German patrons believed they were members of a master race, and they never suspected a black man could understand their language. If Bullard heard any useful information, he mentioned it to Terrier, who could slip away without notice and report to the authorities.

Meanwhile, underneath all this intrigue, criminal groups similar to the Mafia were actively extorting protection money from Parisian nightclubs. On July 2, 1939, Bullard entered L’Escadrille in the early morning hours, expecting to see his club packed as usual and jumping with activity. But only two patrons were hanging out at the bar.

Bullard looked stunned. “What’s going on—”

The bartender held his finger up to his lips and pointed toward the men’s room.

Bullard entered the restroom and saw a Corsican gang member named Justin Perretti reflected in the mirrors. He was swaying and cursing like a madman.

“What’s wrong, Justin?” Bullard asked.

“You know what’s wrong,” Perretti replied. “And I’m going to take care of it—and you!”

Bullard thought Perretti was just drunk. Bullard grabbed his arms, held them behind him and marched him out the front door, knocking over a vase of flowers on the piano in the process. Bullard certainly didn’t need a drunk driving off his business. But a little while later, Perretti showed up again and immediately went into the restroom again.

Bullard confronted Perretti again. “Why’d you come back?”

Perretti answered by whipping out a large knife and lunging at Bullard. He sidestepped, knocked the knife out of Perretti’s hand and again marched him outside onto the sidewalk.

“This is your last night on earth, Bullard,” Perretti said. He brushed off his sleeves. “How about calling me a taxi?”

The doorman called a taxi, and Perretti drove off. Bullard hoped it was the last he’d see of him, at least until he was sober. Bullard turned his attention to mopping up the water that had spilled inside his piano. Half an hour later, Bullard looked up and saw a crazed-looking Perretti pointing a Luger pistol at him.

“I’m going to kill you, Bullard.”

Bullard slowly walked toward Perretti, trying to calm him down. As soon as Bullard got close enough, he slapped Perretti’s gun arm down just as the gun fired. Pain stabbed Bullard in his stomach.

Bullard grabbed Perretti, holding his gun arm behind his back and wrestling him to the floor. Perretti kept firing and shot himself in the back. A customer threw a bottle to Bullard. He caught it and pounded Perretti on the head with the bottle, fracturing his skull.

Customers screamed for Bullard to stop, “You’re killing him!”

Bullard finally realized what he was doing and tossed the bottle aside. He stood up. His stomach was really burning. Blood ran down his right leg, soaking his pants. Customers hailed a taxi, and Bullard sped off to the nearest hospital.

“Bullard,” the doctor said, “I think your intestines and internal organs have been punctured. The bullet entered your stomach and came out your right hip. We cannot repair the damage. There is nothing we can do.” The doctor handed a note to a nurse. “We will observe you for 24 hours, but you cannot eat or drink anything.”

Late the next day, the doctor looked in on Bullard. He sounded amazed that Bullard was still alive. “How do you feel?”

“Hungry.”

The doctor laughed. “You won’t die, will you?” He ordered a small portion of baby food and mashed potatoes. “Let’s see how you do.”

By the next day, Bullard was complaining that he wanted some real food, so each day he was given a bit more to eat. On the fifth day in the hospital, Bullard successfully insisted on his discharge. He wanted to return home to recover there.

While Bullard was in the hospital, Terrier had returned to Paris after an assignment. She was investigating the shooting and had discovered some interesting information about Perretti, but she couldn’t visit Bullard in the hospital for fear of arousing suspicion. After he was released, though, Terrier informed Bullard that Perretti—although a gangster—was fiercely pro-French and anti-German.

Perretti had thought Bullard was a German sympathizer because he understood German too well and was spending too much time around his German customers. In his drunken condition, Perretti thought Bullard was an enemy agent, and it was his patriotic duty to kill him.

Bullard suddenly felt terrible. He wondered if both Perretti and he were working for the French Underground. He hoped Perretti would live.

A week later, Leplanquais and a group of policemen showed up at Bullard’s apartment. “You’ve done very well,” Leplanquais said. “You are now a full member of the Underground.”

Bullard hesitated. “What about my daughters if the Germans occupy Paris? They could kill Jacqueline and Lolita because of my Underground membership.”

“Tut, tut. Remember, we promised to take care of them if anything happens to you. It’s a promise we will keep.”

“In that case, I will do my best,” Bullard replied. “I look forward to continue working with you.”

War Breaks Out Again

On September 1, 1939, German forces attacked Poland. Two days later, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany because they had alliances with Poland.

By October, Germany completely occupied Poland. As a precaution against German air attacks, French authorities imposed nightly blackouts in Paris at sundown. American officials ordered American citizens without urgent business in Paris to return to the United States. Bullard wasn’t about to leave, however. He was committed to his Underground espionage work even though he knew the Germans would kill him if they discovered he was a spy.

Bullard was now even more concerned about his daughters, who attended school south of Paris. He wanted their company, so he removed them from school and brought them home. By the time Jacqueline and Lolita arrived home in early 1940, Bullard’s business had fallen off drastically because of the nightly blackouts. Most foreigners and their money had left Paris. Bullard was forced to close both his nightclub and gymnasium.

Bullard’s money was dwindling fast and expenses were piling up. He was pleased when the wealthy widow, Mrs. June Jewitt James, invited him to work for her. Mrs. James also invited Bullard and his daughters to live at her large château in Neuilly—an offer he gratefully accepted.

Bullard worked for her as a chauffeur and masseur. He answered the phones and made sure all the rooms were clean. At the many formal dinners Mrs. James gave for French and American dignitaries, he also worked as a waiter. On those occasions, he would wear his dress uniform displaying all his medals.

One day, a champagne luncheon was scheduled to honor Mrs. James’s official donation of many ambulances she had purchased for France. American and French flags flew high on poles above her mansion. Among the many guests was Dr. Gros, who was still the administrator at the local hospital.

Dr. Gros motioned to Bullard, who was dressed in his uniform and carrying a tray of drinks. The doctor selected a glass of champagne and examined Bullard. Normally, Dr. Gros would have pretended not to know him, but this time he spoke. “Bullard,” he said, pointing to a medal, “I didn’t know you had the Medaille Militaire.”

Bullard stiffened and sarcastically answered, “Oh, I thought you kept all my records—just as you kept the scroll that was issued to me and every other member of the Flying Corps by the French government.”

Dr. Gros’s jaw tightened. He looked like he was going to say something. His face flushed red. He turned and walked away.

That felt good, Bullard thought. I hope I never see that man again. He tried to put Dr. Gros out of his mind as he continued serving drinks.

Resistance

A few weeks after the champagne luncheon and Bullard’s encounter with Dr. Gros, Inspector Leplanquais ordered him back to Paris. “Bullard, you are now in the Resistance effort fighting against Germans instead of merely gathering information.”

Bullard nodded and listened intently.

“The Germans have invaded northeastern France. Millions of refugees are moving south toward Paris.”

Grim-faced, Bullard wasn’t totally convinced that the Germans could actually take Paris. But he would make sure Terrier, his Underground partner, took care of his teenage daughters while he did his part in the fight against the Germans.

“I’m not one to run away from a fight, Inspector. I’m going to rejoin my old outfit—the 170th Infantry. I heard they’re about a hundred miles east of Paris.”

“Ah, Bullard. It will be their gain, our loss. Good luck.”

At his apartment, Bullard loaded a knapsack with canned food, sausages and bread. His daughters also included the two-volume history of the Lafayette Flying Corps, which mentioned him. He contacted Terrier and made sure his daughters had enough food and supplies before he left. Then, after stuffing some money in his pocket, Bullard set out to find his old infantry regiment. He took the subway as far as Porte D’Italie on the edge of Paris and then set out on foot. Joining other soldiers headed toward the lines, he walked all day and night, fighting against the tide of terrified civilians fleeing in the opposite direction.

Some of the refugees told Bullard that the Germans had already captured the area that he was headed for. There was no sense in continuing toward the lines. After a day and a half of walking, a weary Bullard turned around and headed back to Paris. It took another three days and nights before he reached Porte D’Italie where he had originally departed Paris for the front lines.

French police were waiting. “You cannot enter,” they informed Bullard and the other refugees trying to enter Paris. “We are under orders to stop everyone.”

How would he tell his daughters that he was okay? He tried to sneak into the city at several different points, but was always turned away. Rumors spread that the French 51st Infantry was fighting south of Paris. Bullard finally decided to head there and join in the battle.

Hordes of people fleeing southward filled the roads. Bullard joined them, diving for cover whenever a German Stuka flew over and dropped bombs on the refugees. After more than a day and 50 miles, the town of Chartres came into sight.

By chance, Bullard spied a familiar black face among the refugees. It was a friend named Bob Scanlon, a boxer and fellow legionnaire in the last war. Bullard didn’t feel so alone anymore. The two arrived in Chartres near the busy railroad station, which had Red Cross railcars filled with wounded French soldiers headed for hospitals across France.

Without warning, the sky filled with the high-pitched shrieks of diving Stukas and the whistling of bombs. Explosions erupted around the station, tossing debris into the air and twisting rails like pretzels.

Bullard threw himself on the ground. Scanlon dove into a crater about 20 feet away. A terrible flash of heat and a tremendous boom washed over Bullard. As the Stukas flew off, Bullard lifted his head and looked for his friend. Nothing but smoke rose from the hole where Scanlon had sought safety. Bullard ran over to the crater, dumbstruck. Nothing was there. Absolutely nothing.

Horrors surrounded Bullard. Body parts lay scattered everywhere. A woman’s body lay nearby—sliced in half. Her child shrieked, “Mama! Mama!”

Bullard left for Orleans, experiencing even more horrors along the road. People fought each other for any scrap of food or drop of water. Women gave birth alongside the road. When people had to answer nature’s call, they did openly without any privacy—there simply was none. No one noticed, anyway. Everyone was just trying to stay alive.

On June 15, Bullard reached Orleans and offered his services at the temporary barracks of the 51st Infantry.

The commanding officer appeared. He stared at Bullard. “Bullard! Is that you?”

Bullard stared back at the officer. “Major Bader!”

They embraced.

Bullard stepped back. “I haven’t seen you since Verdun, Major Bader. You were a lieutenant then.”

“And you were a corporal manning a machine gun.” Major Bader rubbed his chin for a second. “And you will man one again. I’m assigning you to a machine gun company on the south side of the Loire River. You must hold back the Germans on the north side.”

That night, Bullard and his machine gun company fought valiantly, holding back the Germans until midnight. Heavy German artillery then bombarded Orleans, set it on fire and forced the French soldiers to retreat. For the next three days, the French kept falling back and defending more towns, only to be driven off by the more mobile German infantry.

On June 18, Bullard and the 51st Infantry reached the old French town of Le Blanc, under heavy artillery fire from huge German 88mm cannons. Bullard saw a scene of utter devastation and ruin. The continuous bombardment shook the ground and flung debris and dirt high into the sky.

Bullard carried a light machine gun and cautiously entered a street with some other soldiers. He heard a familiar whistling sound. Then nothing. A blinding flash of light. A deafening explosion. The powerful blast lifted Bullard into the air and flung him across the street.

He didn’t feel the shrapnel shard when it gouged the skin over his right eye. He didn’t feel his spine fracture. But he felt a terrible blow when he landed and his head smashed into a wall.

When he came to, he discovered that 11 of his comrades had been killed and 16 wounded from the shell that had exploded. If his head hadn’t glanced off the wall at an angle that had softened the blow, he knew he would have been one of the dead, too.

The next day, Bullard found he couldn’t fight any longer. He was in intense pain. His neck and back hurt, and he had a gash in his forehead.

Major Bader feared Bullard would be executed by the Nazis because he was black, a member of the French Resistance, and a hero of the Great War. Bullard was ordered to leave France for Spain through Biarritz. There he would be safe—for the time being.

“Here’s a safe-conduct pass, Bullard.” The major handed him some paperwork. “Good luck. But you must leave immediately.”

Bullard grabbed a rifle for a crutch and hobbled toward Spain.

Bullard headed for the town of Angoulême about a day’s journey on his way toward Biarritz, where he hoped he could find safe passage into neutral Spain. He walked the best he could, leaning on his rifle. He fought shooting pain as he slowly took each step. Eventually, it dawned on him that if he were captured with a gun, he would be instantly shot. He found a large stick to use as a cane and tossed his rifle into some bushes.

Because Bullard was wearing his uniform and medals, the occasional truck heading in his direction would offer him a lift. Twenty-four hours later, Bullard saw the French town of Angoulême and its military hospital appear in the distance. And none too soon, Bullard thought. His pain was so intense, he couldn’t walk much farther.

Bullard finally made it into the hospital, which was filled with wounded men. By an astounding coincidence, Bullard knew the doctor on duty: Dr. H. C. de Vaux, who had been a medic at Verdun. Dr. Vaux was also one of the grateful doctors at the American Hospital in Paris where Bullard and other musicians had played at no cost.

“Bullard,” Dr. Vaux said, “I can’t believe it’s you.”

Bullard couldn’t believe it, either. He sat down while Dr. de Vaux examined him.

“Your spine is misaligned and you have a split vertebra.” The doctor picked up a syringe and injected Bullard with a painkiller. He wrapped Bullard’s back tightly with bandages. “This will help support your spine.” Finally, he placed a bandage over Bullard’s right eye.

The doctor sat down and looked earnestly at him. “It’s too dangerous for you here. And you can’t go back to Paris. You must get out of France as soon as possible.” He gave Bullard some fresh water and six cans of sardines. “Good luck. I’m sorry, but I must look after the other wounded now.” The doctor shook Bullard’s hand and walked away.

On the road, Bullard traded three cans of his sardines for a soldier’s bicycle and pedaled toward Biarritz. In the early hours of June 22, he found the American consulate office and took a place in line with other waiting Americans. He stretched out on the ground to sleep until the consulate opened.

McWilliams, the American consul, arrived and opened the office early. When Bullard’s turn came, McWilliams questioned him and discovered who he actually was. “You’d better get out of that uniform,” McWilliams said. “There are German military officers in the area staying at my hotel and, if they see you . . .”

Hearing about Bullard’s dilemma, other Americans in line offered him a shirt and trousers. Bullard quickly changed into civilian clothes.

“Okay, now give me your passport,” McWilliams ordered.

“Passport?” Bullard looked stricken. “I don’t have a passport. Americans didn’t need passports when I came to France.”

“Then how can we prove you’re an American?” The consul tapped his head. “Where were you born?”

“Columbus, Georgia.”

“I’ve visited there. What river flows through Columbus?”

“The Chattahoochee.”

“What’s the name of the town across the river?”

“Phenix City if you turn right, Girard if you turn left.”

“Hmm. Wait over there.” The consul pointed to a chair.

While Bullard sat awaiting his fate, two Americans he knew appeared in line—Colonel Sparks of the American Legion in Paris and R. Craine Gartz, one of his massage clients. The two Americans spoke with McWilliams and confirmed Bullard’s American citizenship.

“Okay,” the consul said, “that’s good enough for me, but you’ll have to get your passport at the Office of the Consul General in Bordeaux. And you’ll have to leave your identification papers here in case the Germans grab you.” He handed Bullard a passport application.

Bullard knew that Bordeaux was about 100 miles away, but what else could he do? He hopped on his bicycle and pedaled for two days and nights until he reached the consulate, in great pain and totally exhausted. He slept for a few hours and finally met with the American consul. After the consul took Bullard’s photograph, he was issued a passport and given $20 from the American government.

When Bullard left the consulate, it was late in the afternoon. His bicycle was missing. He took another bicycle and headed back to Biarritz, arriving there the night of June 29. He thought it ironic that it wouldn’t be long before the Germans would be enjoying the beaches in Biarritz where he had once honeymooned.

The next day, Bullard had a stroke of luck. He caught a ride with an old friend, who was driving an ambulance filled with Americans trying to leave France. Unfortunately, the roads were so filled with traffic they could get only as far as the small French seaport town of St. Jean de Luz. By the afternoon of the next day, they made their way at last to the French town of Hendaye and the International Bridge into Spain where safety and escape lay.

Then Bullard ran into yet another old friend and ex-legionnaire who was working for the Spanish customs office. Bullard’s old comrade expedited his entry into Spain, but it wasn’t until the wee hours of the next morning, July 2, when Bullard actually set foot on Spanish soil.

After resting for several days in a hotel reserved by the Red Cross, Bullard boarded a train for Lisbon, Portugal. The American steamship, Manhattan, was waiting there to transport hundreds of Americans back home.

On July 12, 1940, Bullard embarked for the United States—a land he hadn’t seen in 30 years.

As Bullard watched Europe recede into the distance, he wondered if he would ever see his daughters again.