7

New York

America

Six days later, the Manhattan arrived in New York. Bullard was thrilled to see the Statue of Liberty pass by as his ship headed for the docks. He hoped the attitudes in America had changed in the years he had lived overseas.

Jack Spector, the former commander of the Paris American Legion Post, was waiting at the dock to greet the arriving American veterans of the Great War. Bullard belonged to that post, so he listened with great interest as Spector talked to the veterans who had gathered around him.

“I have arranged hotel reservations for all of you,” Spector announced. Turning to Bullard, he tried to hide a smirk. “That is, except for you, Bullard. I didn’t know you were with the group.”

Bullard was crestfallen. I guess things haven’t changed that much. Fortunately, a fellow soldier on the ship gave him a few dollars to rent a room. That night Bullard stayed in a room on Seventh Avenue, but eventually he found an apartment at 80 East 116th Street in Harlem, where he took up permanent residence.

One of Bullard’s first jobs was working as a security guard in Brooklyn at a U.S. Army base. He traveled to work every day on a ferry that carried a number of government workers. As the ferry was docking one day, the passengers crowded forward to exit the boat. A white worker thought Bullard was taking too long. He pushed Bullard forward and yelled, “You black bastard!”

Bullard swung and knocked the worker down. As the swearing worker got to his feet, the angry crowd closed in on Bullard. He thought he might actually get killed.

Suddenly, a man stepped in front of Bullard and yelled “Stop!” He flashed an F.B.I. badge. “I saw everything. This white man insulted the black man. Go ashore and go to work.”

The agent turned his attention to the white man. “And you—you apologize to this man. He’s fought Germans for you and has won more medals than you or your family will get in a lifetime.”

Bullard realized then that it was probably the F.B.I.’s business to know everything about every government worker. The other worker meekly apologized to Bullard.

The agent let the man go on his way and turned to Bullard. “Those kind of people make me sick. Is there anything else I can do for you?”

“How about a job as a longshoreman at the navy base on Staten Island? They get paid a lot more than I do.”

The next day, Bullard had a job as a longshoreman. The job required heavy lifting, which was very painful for Bullard, but he would need the extra money to support his daughters if he could somehow bring them to New York. He hadn’t heard anything from Jacqueline or Lolita, though, and he worried about them every day.

By the fall of 1940, Bullard felt it was time for action to get his daughters. He traveled by train to Washington, D.C. and presented his case to officials. They promised to take up his cause. Bullard traveled back to New York and waited impatiently for news.

In January 1941, Bullard received two telegrams stating that arrangements were being made to transport his daughters to the United States. He was ecstatic. He read and re-read the telegrams.

Finally, on a cold, snowy February 3, the Exeter arrived at a Jersey City dock with Lolita and Jacqueline—now 14 and 16 years old. With tears in his eyes, Bullard hugged and kissed his daughters. He hadn’t seen them for almost a year. He took them home to New York to learn English and continue their schooling.

Bullard had been worried for a long time about his daughters trapped in France. He had been through terrible ordeals while fighting in France and trying to escape. And his spinal injury gave him great pain. He needed a well-earned rest, so in March of 1941 he checked into a French hospital in New York that treated veterans of the Great War.

While lying in bed in the hospital, Bullard was startled one day by a knock on his door. “Come in.”

Bob Scanlon stood in the doorway.

The last time Bullard saw Scanlon, he thought Scanlon was killed by a bomb in Chartres. “It can’t be,” he exclaimed. “You’re supposed to be dead. Are you a ghost?”

“No.” Scanlon grinned. “Somehow I survived that blast with only minor injuries. I was thrown clear, and when I came to, you were gone.”

“I can’t believe it. Sit down and let’s talk.”

In the early summer, Bullard was released from the hospital and he returned to work.

In the fall of 1942, an invitation arrived at Bullard’s apartment for a dinner at the New York Paris Hotel. The special event was for Paris American Legion members. Bullard was still a member, and he looked forward to attending the dinner. Shortly before the event, however, he received an anonymous letter mailed from New York and postmarked November 22:

Dear Comrade,

Your extended sojourn abroad has perhaps made you forget that in the States white and colored people do not mix at social functions.

It would be to your advantage not to attend the dinner on Monday night or to join in any social activities of Paris Post No. 1 in the future.

Infuriated, Bullard sent a copy of the letter to Jack Spector—the former Paris American Legion Post commander—who had slighted Bullard on the dock when he arrived from France. Bullard expressed his dismay at the insult, but he never received any acknowledgment. Not one to back down, though, Bullard left his daughters at home and attended the dinner—which thankfully ended without any incidents.

After WWII ended in 1945, Bullard decided to visit his hometown of Columbus, Georgia. While in France, he had heard his brother had been lynched over a land dispute, but he thought he might find some other family members still living there.

Bullard discovered that his house and others had been torn down to make way for apartment buildings. He couldn’t find any of his brothers or sisters. And while he was visiting Columbus, he was treated poorly. Disappointed at how things hadn’t changed, Bullard left Georgia for New York and never returned.

Through the years, Bullard found himself involved in other racial confrontations. In the late summer of 1949, he was beaten by police who were guarding a concert in a park outside New York.

And when Bullard boarded a bus in the Peekskill Mountains, the driver told him to “sit in the rear.” Bullard refused. The driver insulted him and then he threw a punch at the driver, and a fistfight erupted. The driver punched Bullard in the face several times, injuring his left eye. He lost most of the sight in that eye and had to wear glasses from then on.

Bullard toured Europe for a while as an interpreter for Louis Armstrong. In 1954, he was invited by the French government—all expenses paid—to the Bastille Day ceremonies in Paris. Bullard and other French war veterans relit the eternal flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. He also placed a wreath of flowers beside the tomb under the Arc de Triomphe.

Five years later, on Bullard’s 64th birthday—October 9, 1959—he was in the New York French Consulate on Fifth Avenue. The occasion was a formal ceremony to honor Bullard’s distinguished military and civilian service to France. The French consul pinned a Legion of Honor medal on Bullard’s lapel—his fifteenth medal—which made him a Knight of the Legion of Honor.

Bullard places a wreath at France’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, 1954.

His daughters and other dignitaries heard Bullard proudly say in French: “I have served France the best I could. France taught me the true meaning of liberty, equality and fraternity. My services to France can never repay all I owe her.”

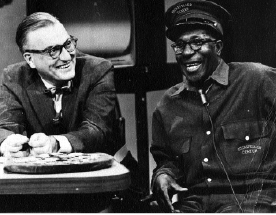

By that time of his life, Bullard was working as an elevator operator in Rockefeller Center. He always wore his medals on his elevator uniform. Producers of NBC’s Today Show, headquartered in the building, took notice. They arranged for Bullard to be interviewed on television by host Dave Garroway. Bullard described his war years to the viewers and told the viewers how he earned the 15 medals that he held up in a case for the camera.

Host Dave Garroway interviewed Bullard, appearing in his Rockefeller Center elevator operator’s uniform, on NBC’s Today Show in New York City. Garroway showed off Bullard’s medals to the studio audience.

In the spring of 1960, Bullard received an invitation:

General de Gaulle, President of the French Republic, and Madame de Gaulle, request Mr. Eugene Jacques Bullard to do them the honor of being present at the reception which they are giving at the Armory of the Seventh Infantry Regiment, 643 Park Avenue, at 4:45 p.m., Tuesday, April 26th.

Bullard was thrilled. He dressed in his Legion uniform, wearing all 15 of his medals. When he showed up at the Armory, he was ushered to a table reserved for VIPs.

At 6 p.m., President Charles de Gaulle appeared and gave a brief speech to the large crowd of French notables and Americans who had served France. After his speech, de Gaulle embraced a number of people. Noticing Bullard, he offered his hand, drew him close, and embraced him.

This is the proudest moment of my life, Bullard thought.

Bullard’s medals (left to right): French Aviator Badge, Légion d’Honneur Chevaliers, Médaille Militaire, Croix de Guerre with Bronze Star, Croix du Combattant Volontaire, Croix du Combattant, Médaille des Engages Volontaires WWII, Médaille de la Victoire 1914–1918, Médaille Commemorative Française 1914–1918, Médaille des Forces Française Libres, Insigne des Blessés Militaire, Médaille des Verdun, Médaille des Somme, Médaille des Engagés Volontaires WWI, American Volunteer.