2

Journey

On the Road

Eugene didn’t dare walk along dirt roads. Any farmer driving his wagon to market might recognize him and tell his father. Eugene headed toward the rising sun and walked on the railroad ties, counting them as they passed under him. He thought about his father’s words: “In France, everyone is treated the same” and “a Bullard never gives up.”

As the day got warmer, the ties oozed sticky creosote, and its strong smell filled the air. Occasionally, Eugene walked on top of a rail, balancing himself with his arms out on each side. When he tired of that, he crunched alongside the tracks on the gravel bed, always heading toward what he hoped was France.

After walking all day on the tracks through lonely stretches of woods, Eugene hadn’t seen another person, but his legs and feet were getting tired. As dusk fell, his imagination took over. He’d heard of people getting murdered at night on railroad tracks. He shivered. And what about bears looking for food? He hurried his pace, looking for a dirt road so he could leave the tracks.

Stars emerged in the darkening sky. Eugene forgot about his tired legs and ran until he finally found a dirt road crossing. Relief washed over him, but a new worry soon arose. He thought everyone knew his secret—that he was a runaway.

He tried to avoid people and keep on the move so he wouldn’t look suspicious. But near the crossing he met Tom and Emma, black sharecroppers with 13 children, who took him in for the night. When the family arose early to work the next day, Emma handed Eugene a dollar bill and wished him well on his journey.

That morning, Eugene headed for the nearest station where a few people were waiting for the train. If he bought a ticket himself, Eugene thought, the station agent might recognize him and tell his father.

Eugene got up his courage and approached a friendly looking white man. “How much is a half-fare to Atlanta?”

“A dollar.”

Eugene handed the man a dollar and asked him to please buy a ticket.

Holding his newly purchased ticket, Eugene trembled a bit when he saw the headlights of the train approaching the station. Someone on the train might recognize him. Maybe his father was on the train. He clambered on board, not looking at anyone.

He sat next to a plump black woman, the widow Mary Wood, who struck up a conversation. By the time they reached Atlanta, Mrs. Wood had convinced Eugene to stay overnight with her. The next morning, the widow urged Eugene to stay longer because she had no family and was very lonely.

“But I’m on my way to France,” Eugene said. “And you’re so kind, if I stay with you, I’ll never want to leave.”

After saying his goodbyes to Mrs. Wood, Eugene walked back to the Atlanta train station. But he was too afraid to buy a ticket. His father might be inside. He hurried away and was soon lost in the nearby stockyards.

A young white man noticed Eugene and approached him. “Hey, kid! How would you like to travel with us for a year? You’d get a dollar a week for taking care of our horses and mules.”

Eugene could tell the young man was a gypsy. He knew gypsies treated everyone alike, and he knew they traveled a lot. Maybe even to France. “Do you ever go to France?” he asked.

“Sure we do,” the gypsy said. “We travel all over the world.”

Eugene couldn’t believe his luck. “When do I start?”

The next morning, Eugene showed up at the stockyard and met Levy Stanley, the leader of the gypsy band, who was trading some horses. That night Stanley took Eugene to the gypsy camp, fed him and gave him a place to sleep.

The gypsies taught Eugene how to care for horses—how to ride them and how to make them look younger with homemade medications so they would sell for a higher price.

After a while, Eugene approached the gypsy. “When are we going to travel to other countries—like France—where everyone is treated the same?”

“Well,” Stanley said, rubbing his chin. “It’ll be another two years before we go back to Europe.”

That seemed like an eternity to Eugene. The gypsies had treated him well, but it was time to leave his new friends. He’d have to find France on his own.

To the Sea

Eugene walked along a dusty road, hoping he was headed for France even though he didn’t really know which way to go. He heard hoofbeats behind him and the rattle of buggy wheels. He stepped to the side of the road.

“Whoa.” A white man drew up his horse and buggy next to Eugene. “Hey, boy. You want a ride?”

“Why, thank you, sir.” Eugene hopped on board, thinking that his father was right. Not all white people were bad. “I’m on my way to France.”

The man smiled. “I’m Travis Moreland.” He flicked his whip, and the buggy moved forward. “How ’bout you rest up at my house tonight? I’ll give you somethin’ to eat. And you can sleep in the corn crib.”

The next morning, Eugene was up with the roosters, waiting for Mr. Moreland to appear, so he could say thanks for the hospitality and be on his way. When Moreland showed up, Eugene said his thanks and that he’d be leaving.

“Boy, you don’t even know where you’re goin’,” Moreland said. “Furthermore, I ain’t even gonna let you go.”

“You can’t stop me, sir,” Eugene replied. “I’m on my way to France where everyone’s treated with respect.”

“Don’t talk back to me, boy. If you leave, I’ll hunt you down. Do whatever the missus wants you to do, and go pump some water for my horses and rub them down.”

When Eugene didn’t immediately move, Moreland cursed at him. Eugene winced at some of the names the man called him. But Eugene figured if he worked hard all day, Moreland would think that he had forgotten about going to France. Then Moreland wouldn’t watch him as closely. Eugene knew he would leave the minute there was a chance to escape.

As the sun set, Moreland sat on a chair on his porch and called to Eugene. And called again. “Why don’t you answer me, boy?”

Eugene approached the porch. “You and your wife said I worked well, but you called me nasty names. I’m not staying where people call me names.”

Moreland looked shocked and walked into his house, muttering to himself. Dejected, Eugene sat on a tree stump. He wondered what to do next.

About an hour later, Moreland came out and walked over to Eugene. “Okay, you still can’t leave, but I won’t call you names anymore. What do you want me to call you?”

Eugene brightened. “Call me Eugene or Gypsy, sir.” He picked up a broom and started sweeping.

“I like your attitude, Gypsy. I’m gonna give you 50 cents a day to work around the farmyard.”

It wasn’t long before the hard-working Eugene was promoted to houseboy. Then six months later, Mr. Moreland called Eugene into his parlor.

“Sit down, Gypsy, I got something to tell you.”

Blacks didn’t usually sit down in a white person’s parlor, but Eugene did as he was told.

Mr. Moreland continued. “You’ve worked hard and earned our respect. We like you, but if you want to go away, it’s all right with us.”

Eugene stayed a little while longer, but one morning he said his goodbyes to the Morelands and struck out on his own once more.

In the tiny Georgia town called Sasser, he met a white barber named Matthews who asked Eugene to work as a helper for him. For several months, Eugene swept the barbershop and did odd jobs.

One day Eugene didn’t show up for work. He was lying in bed with a dangerous fever that rose to 105 degrees. Even though Mr. Matthews was very poor, he sent for a doctor and paid for Eugene’s treatment.

While Eugene was recuperating, he began wondering if he had been wrong about white people. Maybe there were good people of all colors. He’d have to travel more and find out.

When Eugene recovered, he knew he had to set out for France again. Mr. Matthews was sorry to see Eugene go, but wished him well and gave him three dollars to help him on his way.

Eugene reached Dawson City, Georgia, and met the Zacharias Turner family who hired him for two dollars a week to do stable work. Eugene, hoping to throw off anyone looking for him, told the Turners his name was “Gypsy.” The Turners bought horses and mules from Texas. They let Eugene break in their new, wild horses when they discovered how well he handled and treated stock.

Eugene was such a natural with horses that the Turners entered him as a jockey in the 1911 Terrell County Fair horserace. He was a sensation. It was very unusual at that time for a black person to ride as a jockey. Eugene, wearing a red and yellow satin jacket, rode his horse easily. He took the lead and thundered over the finish line to win a length-and-a-half in front of the second-place horse.

Even though Eugene became a hero to the area’s black people, he didn’t let it go to his head. Instead, he thought it was time to get serious about moving on. One night he told Mr. Turner that he wanted to go to France “where all colored folks are treated right by everybody.”

Turner was surprised. He thought he treated Eugene so well, he’d given up wanting to travel. “Gypsy,” he said, “when you grow up, I’ll let you go to France, but not before.”

Eugene didn’t say anything more. But starting the next day, he hid clothing and extra coins in the barn for use when the time was right. Four months later, he was told to deliver a buckskin pony to a prison farm in St. Andrews Bay, Florida. After he delivered the horse, he bought a ticket on a narrow-gauge train to Montgomery, Alabama.

After more adventures and some menial jobs in Montgomery, Eugene headed back to Atlanta with $16—a sizable sum in those days. He didn’t know what direction he should travel to look for France, but he found a Seaboard Air Line Railway passenger train headed for Richmond, Virginia. He guessed Richmond was as good a place as any. At midnight, he hid underneath the dining car on its undercarriage. A whole day later, the train stopped on a bridge near Jamestown, Virginia. Thinking he was close to Richmond, a weary Eugene hopped off.

After working a week or so in Jamestown as a laborer for a black bricklayer to earn more money, he tried to figure out which train was going all the way to Richmond. By pure chance, he hid underneath a Chesapeake & Ohio train that didn’t go to Richmond but to Newport News, a seaport on the Atlantic.

When the train finally stopped and the passengers stepped off, Eugene peeked out from underneath the rail car, looking for anyone who might see him. He climbed off his perch and nonchalantly—but carefully—made his way out of the railyard.

The smell of salt air meant one thing to Eugene. He was closer to France. But he needed to find a ship ready to sail, hopefully one that was sailing to the country of his dreams.

He headed toward the glint of the sea.

On His Way

Eugene reached the waterfront on a Saturday. Steamships filled the harbor. He spied one ship that was being loaded. Was that a ship to France?

Hiding behind a barrel, Eugene watched a line of men carrying crates of cabbages onto the steamer. Once he figured out the rhythm of the loading line, he left his hiding spot and inserted himself between two men who didn’t seem to notice. The man in front of Eugene bent forward, and a loader placed a heavy crate on his back. Eugene did the same.

After Eugene walked up the gangway with his load, another pair of men removed it and stacked it with the rest of the cabbage crates. Eugene noticed several large bales of cotton on board. When no one was looking, he quickly hid between two bales.

He soon felt the ship get underway, but he had no idea whether or not it was going to France. After a few hours, the ship stopped. Eugene stayed hidden until he heard men moving the crates. He sneaked out to join another line of men who were now unloading the crates of cabbage and stacking them on the dock.

As before, two men lifted a crate onto Eugene’s back. He walked down the gangway with his load and stacked his crate with the others. He hurried away from the dock and soon found himself downtown in a strange city. Was this France? He noticed a black boy leaning on a lamppost.

“Is this France?” Eugene asked.

The black boy stared at Eugene. “It’s Norfolk, Virginia, stupid.”

“Oh.” I guess I’ll have to try again.

Eugene headed back to the waterfront and spotted a ship with crew members coming ashore for their leave. As each member passed Eugene, he smiled and said hello, but the crew spoke a language he’d never heard before. Eugene asked around and learned the ship was called the Marta Russ. And it was sailing on Monday.

Eugene showed up early the next day and hung around the ship, trying to figure out how to get aboard.

“Hey, kid!” a sailor yelled from the ship. “Come here a second.”

Eugene ran up the gangway.

The sailor handed Eugene a pail and a note. “Would you run an errand to a bar for me?”

“Yessir!” Eugene answered.

Eugene soon returned with the pail filled with beer and handed it to the sailor.

“Here’s a dime, kid.”

“Thanks.” Eugene turned to leave. How am I going to get aboard?

“Hey, kid. Are you hungry?” the sailor asked.

Eugene nodded.

“I’ll get you something to eat.”

Eugene looked around for a hiding place, but the sailor returned with some bread and cheese before Eugene could move a step.

“Thank you, sir,” Eugene said and sat on the deck. While eating his food he noticed a lifeboat that would be the perfect hiding spot. When he finished, Eugene thanked the crew members and left the ship.

Late that night, Eugene sneaked up the ship’s gangway. He carried a sack of sandwiches and fried chicken, enough food—he hoped—to last until he arrived in France. Making sure no one was around, he slipped under the lifeboat’s cover and fell asleep.

When Eugene awoke, he was on the high seas—far out of sight of land. As days slowly passed, Eugene ate all of his food and drank his only bottle of water. His hunger and thirst grew so unbearable he knew he’d have to make his presence known.

Eugene followed the smell of food. He made his way to the ship’s galley and swung open the door, not knowing what to expect.

“Ach du lieber!” cried out an astonished sailor—the same one who had sent Eugene for beer. “What are you doing here?”

“I’m going to France,” Eugene replied. “But I’m really hungry and thirsty.”

“We’re not going to France, and Captain Westphal is going to be very angry,” the sailor said. “Here, eat this food first, and I’ll tell you what to say to the captain.”

Soon Eugene was standing in front of the captain, who didn’t look very happy at the sight of a 16-year-old black stowaway. He thrust his scowling face in front of Eugene. “We should throw you overboard and be done with you.”

Eugene forgot what he was told to say and blurted, “I think the fish have enough to eat.”

The captain straightened up and laughed. “All right, we’re stuck with you. But you’ll have to work. We have about 18 more days before we land.” The captain thought a moment. “Hmm, you can help the boiler crew.”

Starting the next morning, Eugene hauled up countless heavy bags of ashes from the ship’s engine room and emptied them overboard. Even though he was physically large and strong for his age, the work was exhausting and continued for almost three weeks.

Near the end of the voyage, the captain called for Eugene. “We are going to lay over at Aberdeen, Scotland, before continuing to Hamburg, Germany.”

Eugene had no idea where Aberdeen was or—for that matter—where Hamburg was.

The captain frowned and paced with his hands behind his back. “I might keep you on board until we get to Hamburg and then take you back to Norfolk.”

“Oh, please, don’t do that,” cried Eugene. “I don’t want to go back. I want to go to France.”

The captain’s expression softened. “Well, I guess I’ll just have to get rid of you somehow in Aberdeen.” He bent down and spun the combination lock on a safe. “Maritime law says I have to pay you for the work you’ve done.” The captain removed an envelope and counted out some bills.

Eugene couldn’t believe his eyes. He held out his hands and received $25, a huge sum. A commotion from the deck grabbed his attention. The ship was docking. Eugene thanked the captain, shook his hand and ran down the gangplank to Aberdeen.

Eugene looked around. Now I must be closer to France.

Odd Jobs

It didn’t take Eugene long to notice there were no black people around. Wandering the streets of Aberdeen, all he saw were white people who stared at him as they walked by.

Eugene approached one Scot reading a newspaper. “Excuse me, sir, but can you tell me where France is?”

The startled Scot dropped his paper. He stared at Eugene for a second before he regained his composure. “Well, laddie,” he said with a thick Scottish burr, “France is hundreds of miles away.” He pointed south and chuckled. “That way, actually. Across the English Channel.”

Eugene had a hard time understanding the man because of his accent, but it appeared there was another stretch of water to cross. He’d have to go to another city farther south and figure out how to get on another ship.

With a bit of his savings, he purchased a train ticket to Glasgow. Upon arriving in the city, Eugene did not see any black people there, either. The Scottish people who met him sometimes addressed him as “Darky,” but he soon realized they were not trying to insult him. He liked Glasgow. The people were polite and friendly.

After he found a room to rent, Eugene figured he had enough money—if he was careful—to last about a month. He made friends with a number of boys his own age and bought them candies and other treats. Within two weeks, he had no money left.

An organ grinder playing a hurdy-gurdy on the streets noticed Eugene hanging out with his friends and thought he could make more money with a black partner. Eugene needed money, so it wasn’t long before Eugene was dancing and singing for coins.

A few days later an older man approached Eugene. “Hey, Darky, how’d you like to work for us? All you have to do is just keep an eye on things. And the pay is good.”

The man was a riverfront gambler who needed lookouts to warn of police raids. Eugene liked his new job working as a lookout the best of all. The pay was good, and the work was easy. Within a few months, he had saved enough money to move even farther south to England—another step closer to France.

One more train trip deposited him in Liverpool, England, home of a large seaport. Perfect. I can get a job on the docks. Within a few days, he was lugging heavy slabs of frozen meat off the ships, making about two dollars a day.

As the days passed, Eugene noticed his body was getting stronger and his muscles were getting larger. But after a month of working, he was so exhausted he decided to look for something less strenuous.

Eugene worked a short time as an assistant on a fish wagon, then nabbed a job in an amusement park. On weekends he would stick his head through a hole in a canvas sheet in a booth, and let customers throw soft rubber balls at him. He attracted a lot of business because the crowds had never seen a black person before. Fortunately, Eugene had quick reflexes and most of the balls—even though they were soft—missed him.

Working only on the weekends meant Eugene had time to explore Liverpool and learn the streets. One day he rounded a corner and stopped in front of Chris Baldwin’s Gymnasium. He wondered what was inside and stepped through the front door.

Learning to Fight

Eugene shut the door behind him. The smell of sweat permeated the air. Clanks and thumps echoed between the walls. Men were lifting weights, jumping rope and punching heavy bags that hung from the ceiling. In the rear of the gym, a man yelled directions at two other men who were throwing punches at each other and dancing around in a boxing ring. A gong sounded. The men stopped punching, grabbed their towels and clambered over the ropes.

The man who had been yelling at the boxers was Chris Baldwin—the owner. He spied Eugene standing with his mouth agape. “You come to join us, young man?”

“I was just looking around, sir,” Eugene replied. “I wasn’t sure what was in here.”

Baldwin stood in front of Eugene and wiped his forehead with his sleeve. “We train championship boxers.” He looked at Eugene carefully as if measuring him. “Hmm. Average height. A little scrawny. How old are you?”

“Sixteen, sir.”

“Maybe if you’d hang around, we could show you how to become a boxer.” Baldwin flexed his arms to show off his muscles. “Lemme see you do that.”

Eugene held up his arms, flexing them as hard as he could to make his teenage muscles bulge.

“Hmm,” Baldwin said. “Not bad, but if you’re gonna be a boxer . . . you do want to be a boxer, don’t you?”

“Yeah!” That sounded like a great idea to Eugene. “I want to be the best boxer ever.”

“Well, let’s weigh you, and we’ll get started.” Baldwin pointed to a scale in the corner. Eugene stepped on the scale and stood there while Baldwin slid the scale’s weights back and forth. “One hundred twelve pounds. You’ll do as a bantamweight.”

Using money he earned at the amusement park and doing errands, Eugene was soon working out every weekday at the gym. He lifted weights, skipped rope, and boxed with anyone who would step into the ring with him. He never complained, no matter how beat up he was afterward. And he impressed the other boxers with his speed and power. As a result, they showed him different punches and footwork to outbox his opponents.

By the time Eugene turned 17, he had bulked up his body and moved up to the lightweight class. Now he thought he was ready for a real match. But first he had to convince Baldwin. After weeks of Eugene’s persistent pleading for a pro match, Baldwin finally arranged a 10-round match for Eugene on Thursday, November 9, 1911. The Irish boxer Bill Welsh would be his opponent at Liverpool Stadium.

When the night arrived, the boxing lineup also included a welterweight black boxer from the United States—Aaron Lister Brown, known as “the Dixie Kid.” The Kid was paired with Johnny Summers, an English boxer, for a 20-round bout before Eugene’s fight. Brown was known for his lightning-fast reflexes. He liked to fight with his hands at his side and his chin stuck out, daring the other boxer to hit him.

The bell clanged for the second round of the Dixie Kid’s match. The Kid and Summers jabbed and danced around each other until the Kid slugged Summers on the chin with a right uppercut, followed by a smashing left hook to his head. Summers wobbled, his legs buckled, and he crashed unconscious to the canvas. The crowd roared its approval. The referee held the Dixie Kid’s arm up signaling a knockout victory in the second round.

Sooner than Eugene expected, it was his turn. Welsh and Eugene touched gloves and retreated to their corners.

The bell clanged. Round one.

Eugene and the Irish boxer emerged from their corners. They warily tested each other with jabs and the occasional punch. Eugene was determined to win and used every trick he had been taught.

The two fighters slugged each other round after round. When the bell clanged the end of the tenth round, both boxers were thoroughly pummeled and bloodied—but both were still standing. The judges added up their scores. The referee held up Eugene’s arm. The crowd erupted in applause. Eugene had won his first pro fight.

The Dixie Kid had taken a seat in the audience and was watching Eugene’s victory. Impressed with his style, speed, and the fact that he was still standing, Brown approached Eugene with an offer: “How’d you like to come with me to London so’s I can train you?”

Eugene didn’t hesitate. He knew it was his big chance. “Yessir, I’d sure like that.” He held Dixie’s hands between his boxing gloves and shook them. “But let me ask Mr. Baldwin if that’s okay.”

The next day, Eugene found himself in London living with the Dixie Kid, his wife, and their infant daughter. They lived in Mrs. Carter’s Boarding House, along with boxers and entertainers from around the world. It wasn’t long before Eugene was training with the Dixie Kid and earning money by doing errands and odd jobs for the other boxers.

Within a year or so, Brown was finding almost weekly matches for Eugene in boxing clubs around London. He also landed matches in the prestigious Blackfriars Ring—a club where Eugene’s boxing reputation grew with each fight.

Eugene had never been happier, but France was still beckoning to him. He asked the Kid if he could arrange a match for him in Paris.

Months passed.

Then in October 1913, Brown approached Eugene while he was sparring. “I’ve arranged a 10-round match with Georges Forrest. It’ll be in Paris on the 3rd of December.”

Eugene unlaced his gloves and threw them high into the air.

“Yes!” Eugene shouted, dancing in the ring and jabbing at an imaginary opponent. “I’m going to France.”

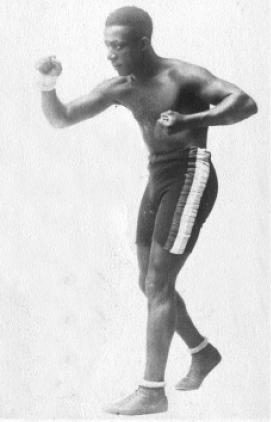

Eugene Bullard began boxing as a teenager and soon began competing internationally in places as far away as Egypt.