“Are you aware it is private property? Why you’ll be asking me to bomb Essen next.”

—Sir Kingsley Wood, British Secretary of State for Air, on plans to set fire to the Black Forest, September 1939

“War will not come again . . . Germany has a more profound impression than any other of the evil that war causes; Germany’s problems cannot be settled by war.”

—Adolf Hitler, August 1934

With the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt made an ardent appeal to the nations involved in the war, and to those about to become involved, to avoid the bombing of undefended cities and towns, and of any targets where civilian casualties might result. Britain, France, and a few weeks later, Germany, all agreed and gave their assurances. RAF Bomber Command found itself encumbered by a bombing policy that was, to say the least, bizarre. It was ordered to refrain from attacking targets of any type on German soil due to the nearly impossible challenge of identifying the purely military ones, and thus avoiding any possibility of hitting civilians. What they could attack were German naval ships moored in harbors or steaming at sea, though not those in port alongside a wharf. They were also allowed to operate over Germany in order to drop propaganda leaflets prepared by the Political Intelligence Department of the British Foreign Office. So, they could hit the German fleet when they could find it, providing no civilian lives were at risk, and they could practice psychological warfare. A joke making the rounds at the time had bomber crews being warned to be sure to untie the leaflet bundles before dropping them lest they hurt someone below. Still, for the leaders in Bomber Command, this odd approach to military engagement came with a silver lining of a sort . . . it bought them time to build strength in manpower, aircraft, and ordnance and to attain some vitally needed reconnaissance and training experience.

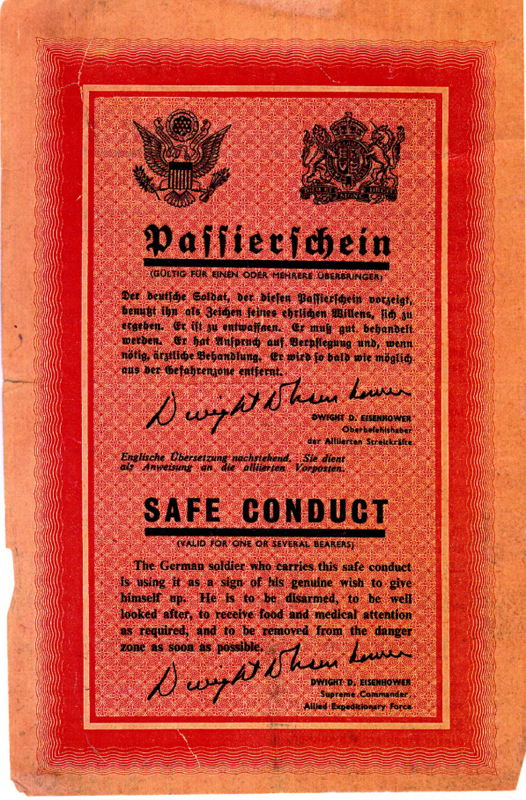

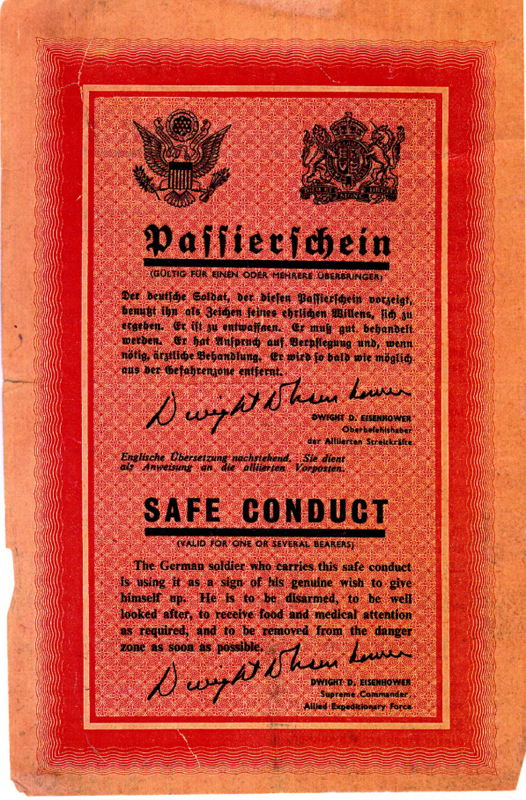

Examples of leaflet types dropped by the American and British air forces during the European air offensive in World War II.

Bomber Command desperately required intelligence about the German enemy and set out to make the best use of this period during which they were prohibited, for the most part, from doing what they were designed to do. They began, instead, on the first night of the war to carry out long-range reconnaissance flights to Germany, and they continued this intelligence-gathering activity throughout the bitter winter of 1939-40. Fliying deep penetration sorties into the German homeland, Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bombers, as well as some Vickers Wellingtons and Handley-Page Hampdens, were utilized to obtain and confirm information about potential bombing targets such as industrial factories, aerodromes, air defenses, power stations, roads, and rail centers. These trips provided invaluable training and experience for the aircrews in extremely demanding conditions over what for them was largely unknown terrain. The missions were ostensibly for the purpose of distributing anti-Nazi propaganda leaflets over selected German towns. After a week of this pamphleteering, the British public expressed its anger over the policy of bombing the Nazis with leaflets while the Nazis were busy bombarding Poland with the real thing. The reaction brought the leaflet campaign to a swift halt. It was resumed a few weeks later, however, though by that point the British government had concluded that its bombing offensive would have to be cranked up a notch or two. The degree to which the leaflets influenced German public opinion is debatable, but not so the importance to the Royal Air Force of the military intelligence and aircrew experience gained through the missions.

In the effort to deliver some 74,000,000 of the leaflets, the Whitley crews found and brought back urgently needed reconnaissance data. This data, combined with that obtained by the Advanced Air Striking Force in its own reconnaissance over western Germany, greatly aided those who would plan and organize the major attacks that Bomber Command was soon to launch. Operationally, they helped to show that even target cities in the most distant parts of Germany could be reached and hit by the British bombers. RAF navigators faced the challenge of finding their way to and from a range of target sites with a foretaste of the troubles they would encounter many times on future raids. Crews had to operate frequently in dense cloud cover, extreme cold, the murky German black-out, the nerve-wracking enemy searchlights and anti-aircraft fire. They contended with these difficulties but suffered most from the icy effects of that particularly savage winter. They found that ice would collect to a thickness of six inches on wings and windscreens. As it accumulated, it gradually caused controls to stick, sometimes rendering the aircraft uncontrollable. They were equipped with de-icing gear but it was often ineffective in the conditions they experienced. Equally ineffective was the heating equipment provided in the aircraft. Added to this was the strange phenomenon of fine, rime ice that would penetrate the aircraft, covering the crew with a white powder that froze on their clothing and equipment. Flight instruments became encrusted with the opaque crystalline ice and frequently froze up.

Another aspect of the leaflet raids was the level of endurance they demanded of the crews. Flown at night and in varying conditions, the raids lasted between six and twelve hours and were unequaled as tests of both navigation and endurance.

According to an Air Ministry account of the leaflet offensive, nearly all of the Whitley bomber crews experienced one common problem: it was all but impossible to lower the turret from which the pamphlets were discharged due to the intense cold. The temperature varied between minus twenty-two and minus thirty-two degrees centigrade. In one aircraft the starboard engine had to be shut down when it caught fire. The Whitley was then in heavy cloud and approximately six inches of ice had formed on its wings. The aircraft went into a dive and it required the strength of both pilots to pull it out at 7,000 feet. They then found that the elevators and rudder were immovable. The wireless operator sent a signal to say that one engine was on fire, and tried to get an immediate “fix” but could not be certain that he was actually transmitting as the glass covering his instruments was thick with ice.

At this point the Whitley was relatively stable but losing altitude at the rate of 2,000 feet a minute. The port engine was stopped and the crew estimated that about four inches of ice was protruding from the inside of the engine cowling. The propeller, the wing leading edges and the windscreen all had a thick ice coating. The pilot ordered his crew to abandon the aircraft but he got no reply from either the front or rear gunners and immediately cancelled the order. It was later discovered that both gunners had been knocked unconscious in the dive and subsequent recovery.

The plane then began a shallow, high-speed dive and the pilots opened the top hatch and a side window to see where they were going. The Whitley broke from the cloud into heavy rain at a height of only 200 feet. The crew saw only thick forest with a small grey patch in the middle, for which they were heading. They skidded the bomber through the treetops and managed to drop it into the small clear field. It careened through a wire fence and skidded broadside into the trees at the far side of the clearing. The engine fire was now extreme and the crew quickly got out of the fuselage and attempted to put out the flames. The pilot found that the extinguisher they carried in the cockpit had discharged in the crash-landing. The wireless operator attacked the fire with the extinguisher from near his crew station.

The bomber had come down in France and, after spending the night in their airplane, the crew was cared for by local inhabitants.

“The entry of the United States into the war is of no consequence at all for Germany. The United States will not be a threat to us for decades—not in 1945 but at the earliest in 1970 or 1980.”

—Adolf Hitler, 12 November 1940 Another Whitley on the leaflet mission that night developed a defect in its oxygen system, creating a shortage of supply to the crew. They successfully dropped their propaganda but by that point both the navigator and the wireless operator were suffering from insufficient oxygen and had to lie down and rest on the floor of the fuselage. The cockpit heating was inoperative and the entire crew was suffering from extreme cold and distress. The pilot and the navigator were experiencing the agonizing onset of frostbite as well as a lack of oxygen. On the homeward journey they descended to 8,000 feet, but the icing grew worse. All windows were covered. The crew heard ice as it was whipped off the propeller blades against the sides of the nose. The pilot had to move the controls continuously to keep them from freezing up. Still, they made it back to base and the bomber landed safely.

A third Whitley on this particular night raid also made a forced landing in France. It was an especially heavy landing and the rear gunner was badly shaken. He emerged from the aircraft and made his way to the nose to have a word with the pilot and found that he was alone. The rest of the crew had bailed out on command of the pilot. Evidently, the intercom had failed and the rear gunner had not heard the order to abandon the airplane, which had somehow landed itself with no one at the controls.

The gunner made his way to a nearby village and came upon his entire crew safe in a café there. They talked about their experiences and the front gunner told how he had been unconscious during his parachute descent. He regained consciousness on his back in a field among a herd of curious but friendly cows. The wireless operator, too, managed to land in a field—of curious and definitely hostile bulls. In full flying kit, the radio man rapidly made for and cleared a four-foot fence. The pilot landed unhurt and the navigator incurred only a sprained ankle. After their reunion in the café the crew were taken to a French hospital where they were treated and released. They were returned to their unit that same day.

Clearly, the principal danger faced by the crews on these early leaftlet raids was weather, but there was the occasional interference by a German night fighter. In an incident where a Me 109 closed to within 500 yards of a Whitley whose leaflets were about to be dropped, the rear gunner reported the presence of the enemy fighter to the pilot. The pilot instructed the rear gunner to hold his fire while the navigator and wireless operator completed the leaflet drop. After a bit the rear gunner reported that it would no longer be necessary for him to take action against the 109 as it had flown into the cloud of released leaflets and had dived away.

Flight Lieutenant Tony O’Neill was one of the first RAF pilots to participate in the leaflet raids. R. D. “Tiny” Cooling, a former Wellington pilot, described O’Neill’s first propaganda attack: “With the outbreak of war not yet twelve hours past, Bomber Command had already launched penetration raids over Hitler’s Reich. The first, by a Blenheim IV of No 139 Squadron, was a photo-reconnaissance mission to Wilhelmshaven. That same night ten Whitley crews were briefed for sorties to Hamburg, Bremen, and the Ruhr; their task to drop thirteen tons of paper, some six million leaflets, on these cities in northwest Germany. In part, it was a propaganda mission, in part a demonstration to the population that the Royal Air Force could roam freely through German skies notwithstanding Hermann Goering’s boast that no enemy bomber would ever penetrate the airspace of the Fatherland.

“Preparation began three days before. A runway was being laid at Linton-on-Ouse, home to No 58 Squadron’s Whitley Mk IIIs, so ten aircraft (three from No 51 Squadron and seven from No 58) were detached to Leconfield to take on their paper load. Code-named ‘Nickels,’ these leaflets would become familiar to bomber crews in all theatres of the war. In obscure Oriental languages they would flutter down over Japanese-occupied territories, over North Africa and the Western Desert they would invite Axis troops to surrender; over occupied Europe they took the form of mini-newspapers like La Revue de Monde Libre or its equivalent in Dutch, Flemish, and German. On 3 September it was a warning addressed to the German people, a forecast of things to come.

“The Whitley was a twin-engined bomber which had entered RAF service in 1937. The Mark III was powered by Armstrong Whitworth’s 845 hp Tiger engines which had a disconcerting habit of blowing off cylinder heads, even complete cylinders, punching holes in the long chord cowlings. Deliveries of the later and much more reliable Merlin-powered Mark V had only begun days before in August.

“Briefing was in the late afternoon, take-off at dusk. The route ran from Leconfield to Borkum, an island off the estuary of the Ems, south along the frontier of Holland to Essen, and then along the Ruhr Valley, scattering bundles of leaflets through the flare chutes of the bombers. The weather forecast, unaffected by security, stemmed from observations less than twelve hours old. Intelligence was a different matter. Information about searchlights, guns, and balloons was based on conjecture and deduction. Navigation would be by dead reckoning aided by any trustworthy radio bearings coaxed from the atmosphere. Release height was set at 16,000 feet. Into the gathering darkness the Whitleys crossed the Yorkshire coast and headed out over the North Sea on their way, for the first time, to Germany.

“The island of Borkum lay below, a black shadow fringed with a grey lace of surf. Cloud covered the German coast, spreading across the hinterland. An unpracticed searchlight crew probed their beam through a distant break in the stratus sheet. Flight Lieutenant O’Neill sat watching the instruments glowing green in the dark, glancing at the port engine and its spinning propeller. Gradually, G-George climbed to the selected height. The crew were in their oxygen masks, which were uncomfortable but bearable, and it was cold.

Four hours out and the Whitley was over the Ruhr. A few heavy shells burst in tiny red sparks in the distance. Inside the gloom of the long metal fuselage the crew began posting bundles of leaflets through the flare chute. There was no oxygen in its vicinity and there were no portable oxygen bottles. In less than ten minutes the two men were exhausted. Two others took their place while those relieved went forward to plug into the main oxygen supply and refresh themselves for a further spell. It was then that the port engine showed the first signs of failure.

“The choice was clear. Two hours to the southwest lay France and friendly territory. There was no point in risking aircraft and crew in a flight through hostile airspace, steadily losing height, then to face the North Sea on a single engine. O’Neill headed toward Rheims, discharging the last few bundles of leaflets as he went. Unfortunately, the route lay across neutral Belgium, but an aircraft in trouble could expect more consideration than one deliberately violating the frontiers of a non-combatant nation, and total cloud cover beneath would help them.

422nd Bomb Squadron CO Lt Col Earle Aber and two crew members awaiting their D-Day takeoff at the Chelveston, England base.

“The Whitley droned on across the Belgian border, past Liege, into France, descending slowly. Then the port engine failed completely, its propeller windmilling in the slipstream (the day of the feathering airscrew still lay in the future). The starboard engine now began showing signs of strain. A landing could not long be delayed, but it was still dark. The cloud layer stretched above them now and ground detail was almost invisible. O’Neill launched a flare. In its light he identified one field large enough for a wheels-up landing. It was nip-and-tuck to line up and creep in over the hedge. A railway embankment loomed up but he was committed. With a loud thump, and the tearing of metal, G-George skated across a vegetable patch. Group Captain O’Neill, DFC, now retired, recalled cabbages bouncing about the cockpit like short-pitched cricket balls as the broken bomb-aiming window sheared them off like a harvester’s knife. The crew emerged unharmed. They had been in the air for seven and three-quarter hours.

“The silence was profound, almost oppressive. An erratic ticking from metal contracting within the cooling engine and the subdued voices of the crew were the only sounds. As the daylight increased, some men emerged from the darker edges of the field and approached cautiously.

“G-George lay inert. The Whitley’s tailplane was festooned with leaflets in German gothic script where the slipstream had trapped them. It was some time before the group of French farmworkers could be persuaded that it was the Royal Air Force which had dropped in on them. From then on the warmth of the welcome became overwhelming. They had landed close to the village of Dormans, near Epernay in the heart of the Champagne country. As news spread, the village was en fete. Eventually transport was found to ferry the fatigued crew to Rheims where a telephone call to Linton notified the squadron of their situation. Finally, the bliss of bed and sleep. On 5 September a De Havilland Rapide flew Lt O’Neill and his crew to Harwell and they were soon back at Linton. Only G-George did not return.

“On 9 April 1940 German forces invaded Denmark and Norway; the ‘Phoney War’ was almost over. Since that first sortie the number of leaflet raids had risen to sixty-nine. Fourteen aircraft were lost. Severe weather caused a four-week break in operations, and over ten days around Christmas and the New Year, Bomber Command flew only shipping searches, but on the night of 12-13 January 1940, Whitleys carried nickels to Prague and Vienna. At the same time Wellingtons and Hampdens joined the fray, in their initial night operations. On 10 May the Western Front erupted as the Luftwaffe savaged Rotterdam. On 11 May Bomber Command carried the first bombs to mainland German targets. Leaflets now took second place. But these operations had been immensely valuable. At low cost a basic cadre had been created upon whose experience the development of the bomber offensive was to build. That warning carried by Tony O’Neill was to prove justified.

“On the night of 8-9 September 1942, I was flying as navigator in Wellington 1342. The target was Frankfurt. Crossing the city we were coned in searchlights and came under intense anti-aircraft fire. We were hit and the starboard engine lost power. We were unable to maintain course. We were hit again and found that we were losing fuel rapidly. We could not maintain altitude and it was obvious that we wouldn’t make England and our base. We crossed out over the coast and took up ditching positions. The wireless operator sent out a distress signal on the Mayday wavelength and clamped down his key. Shortly thereafter, as we were still airborne, he went back to his seat and tapped out the SOS again. I reminded him to bring his Very pistol [flare gun] with him. While climbing over the main spar he slipped and must have squeezed the trigger as a couple of stars shot past my face, burnt through the aircraft fabric and, in so doing, set fire to some leaflets which had blown back during the dropping operation. Between us, we beat out the flames and again took up our ditching positions.

“It was quite misty, and, while holding off just above the water, the starboard engine suddenly cut out; the wing dropped and struck the water, and the poor old Wimpy broke her back. The lights went out and the IFF blew up in a blue flash. I was trapped, but eventually managed to struggle free and was washed out of the fracture in the middle of the fuselage. As I emerged, a couple of packages floated up beside me and I tucked them under each arm and pushed off on my back.

“In my hand was a Woolworth’s torch which was switched on. I heard voices calling but I couldn’t tell from which direction. The pilot, bomb aimer, and wireless operator had got into the dinghy and, guided by my torch, came alongside me. The wireless op seized me by the hair and the others hauled me into the dinghy. Apparently the rear gunner had gone down with the tail.

“It was now 4:30 a.m. and quite dark. We baled water from the dinghy and made ourselves as comfortable as possible. At about 6:30 we heard the sound of an engine and saw a launch in the distance. Not knowing whether it was one of ours or a German, we fired off a marine distress signal. We assumed the launch hadn’t seen us or our signal, as it turned and disappeared from view. Five hours later we again heard and saw a launch. The bomb aimer tried to fire another distress signal, but the igniting tape broke so he used his thumb to ignite the flare, and burnt the palm of his hand in so doing. The launch saw our signal and headed towards us. As it approached we saw the RAF roundels on the hull. The launch crew put out a scramble net over the side and with assistance we climbed aboard. They told us that when we first saw them at 6:30, they were recalled due to a naval action taking place in the vicinity (about ten miles from the Channel Islands). When they got back to their base, their CO sent them out again. They had plotted our position from our Mayday signal. We were given dry clothes, rum, and hot coffee by the launch crew as we headed for the Needles on the Isle of Wight.”

—John Holmes, Nos 102 and 142 Squadrons, RAF

“The bus made its way slowly to Madingley along the winding country roads, through villages undisturbed by the passage of time, full of mellow stone and thatched cottages. It was raining fitfully and as I peered through the raindrops on the bus window, my mind was straining to remember the events that led up to fifteen Cheddington airmen being buried in that military cemetery, and two more being listed on the Wall of Missing. Nine of those still buried there had been from my unit, the 406th Bombardment Squadron, Eighth U.S. Army Air Force.

“There was Lieutenant Colonel Earle J. Aber, Jr, our squadron commander. I don’t think anyone who had been in the squadron will ever forget how his remains had come to be buried in this hallowed ground, which had been donated by Cambridge University to the American Battle Monuments Commission. Just as the bus arrived at the cemetery, the rain stopped and the sun broke through and shone brightly on the 3,811 white crosses and Stars of David headstones marking the graves of American servicemen from every state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines.

“As I wandered along the paths, looking at each perfectly manicured plot for the graves of the airmen who had been stationed at Cheddington, I found that my task had been made easier by the thoughtful cemetery superintendent who had marked all fifteen graves with a miniature U.S. flag. I found the simple white cross with the inscription EARLE J. ABER, JR. LT COL., 406 BOMB SQ., 305 BOMB GROUP (H), WISCONSIN, MAR. 4, 1945. What it didn’t say was that he had been born on 19 June 1919, in Racine, Wisconsin. Young in years, he had been endearingly known as ‘The Old Man’ by all of us in the squadron. Like so many squadron and group commanders in Eighth Air Force units during World War II, he had catapulted to the top as the result of a combination of circumstances. He had been a top-notch pilot who had survived almost fifty night combat missions. Group and Wing Headquarters had recognized his operational and leadership qualities by making him the Operations Officer and promoting him to the rank of Major. And finally, and this happened all too often during the war, he had become the squadron commander when his predecessor had crashed and was killed. In Lt Col Aber, the 406th had an outstanding leader with infectious energy and inspirational leadership. He was well liked by all his personnel, in spite of the high standards and constant demands for excellence on the part of air crew and ground crew alike.

“I had flown my fifty-first and last combat mission as his navigator on the night of 5 February 1945 when we went to Frankfurt. We had been targeted one of the largest and most heavily defended cities in Germany and had expected to encounter intense anti-aircraft fire and nightfighter activity from the Luftwaffe, but it turned out to be a relatively uneventful flight, for which I was extremely grateful. That was not the case a month later, on the night of 4 March, when Lt Col Aber decided to fly with a ‘make-up’ crew, personnel who usually flew with a regular crew, but had missed a previously scheduled mission for some reason, and were trying to catch up with their fellow crew members so they could finish their tour together.

“This mission was expected to be a ‘milk run,’ an easy trip to the Netherlands, dropping leaflets on Amsterdam, Utrecht, and Rotterdam. The flight out of England and over the targets was routine, and the crew could visualize the news leaflets fluttering down to be eagerly picked up the next morning by the Dutch people.

“Only two weeks earlier, on 14 February, the Dutch Prime Minister, Pieter Gerbrandy, had visited Cheddington and, in a highly emotional speech, told the 406th Squadron how much it meant to the Dutch populace to receive the leaflets with their accurate recounting of war events.

Reminders of the presence of RAF and USAAF airmen who “smoked” their names and wartime units on the ceiling of the Eagle pub in Cambridge during the Second World War.

“Shortly after Lt Col Aber had turned the B-17 westward, after the last leaflet bomb had been dropped, and started the slow descent toward the designated entry point into England at Clacton-on-Sea, a series of events came together to produce one of the most ironic endings to an Eighth Air Force bomber mission of the war. In the days preceding the mission, the German Air Force had cleverly used Ju 88s at night to make hit-and-run bombing missions against airfields just inside the east coast of England, usually when RAF bombers were returning from their own raids, in order to add further confusion to the situation. After several nights of such activities, the British anti-aircraft batteries along the coastline were understandably tired, frustrated, and ‘trigger happy.’ Unknown to Lt Col Aber and his crew, which included co-pilot Lt Maurice Harper, and the navigator, Captain Paul Stonerock, who also planned to make this flight his last mission, the Ju 88s had carried out another attack and were heading back to Germany.

“As the B-17 passed through 10,000 feet on the descent, a loud noise was heard and the plane shook violently. The crew didn’t know what had happened. They first thought that they had collided with another aircraft. Then the plane was hit again, and all aboard quickly realized that the British anti-aircraft batteries had zeroed in on them instead of on an outgoing Ju 88. With engines on fire and flight controls shot away, Lt Col Aber and Lt Harper struggled to keep the plane in level flight. Finally, Aber, in a strong, unemotional voice, directed the crew to bale out. Miraculously, one by one, the crew was able to leave the bomber. In some cases, their parachutes opened only seconds before they touched down on the marshy land near the cold and unforgiving North Sea. All that is, except Aber and Harper. Time had run out for them before they could leave the plane. The rest of the crew saw a fireball as the stricken aircraft crashed into the ground nearby. The next day when search crews went to the crash site, all they found of this great airman and outstanding commander was a hand with his ring on it.

“As I prepared to leave Lt Col Aber’s grave site to rejoin the others, I found myself saluting and saying a few words of prayer. After we had climbed aboard the bus for the return trip to Luton, I looked back across this beautifully landscaped and very special bit of England, and Thornton Wilder’s words came to mind: ‘All that we can know about those we have loved and lost is that they would wish us to remember them with a more intensified realization of their reality. What is essential does not die but clarifies. The highest tribute to the dead is not grief but gratitude.’”

—Brian Gunderson, 305th Bomb Group, Eighth USAAF

In its psychological warfare operations in World War II, the U.S. Eighth Army Air Force dropped a total of 1,493,760,000 propaganda leaflets over German-occupied Europe.