At the start of the Battle of Britain in July 1940, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, still smarting from the set-back at Dunkirk, wrote to Lord Beaverbrook, his Minister of aircraft production, “When I look round to see how we can win the war I see that there is only one sure path . . . and that is absolutely devastating, exterminating attack by very heavy bombers from this country upon the Nazi homeland. We must be able to overwhelm them by this means, without which I do not see a way through.”

Shortly before seven in the evening of 17 August 1942, all twelve of the 97th Bomb Group B-17Es that had taken off from a base at Grafton Underwood, Northamptonshire, three and a half hours earlier were sighted from the Grafton control tower. They approached the field from the west and in the next few minutes all landed, having returned safely from the U.S. Eighth Army Air Force’s first heavy bombing raid of World War II.

Their target that summer afternoon had been the huge Rouen-Sotteville rail marshaling yards near the French coast. Twice in the preceding week the raid had been scrubbed due to what the mission planners decided was unacceptable weather.

The B-17s on the mission that day all had nicknames. They were called Yankee Doodle, Dixie Demo, Johnny Reb, Big Punk, The Big Bitch, Heidi Ho, Birmingham Blitzkrieg, Butcher Shop, Prowler, Baby Doll, The Berlin Sleeper and Peggy D. Colonel Frank Armstrong had led the mission in Butcher Shop. Flying in Yankee Doodle was Brigadier General Ira Eaker, Commander of Eighth Bomber Command, the new kids on the block, untried and unproven. Ira Eaker had come to England at the head of a small group of U.S. Army Air Force officers to work with the British in arranging for the presence of the first American combat flying units to be based there. He and his staff focused immediately on three needs: To mount a bomber offensive against German-occupied Europe in conjunction with the RAF; to begin fighter operations in conjunction with the RAF—at first in defense of the British Isles and later in the escort of daylight bombers; to organize the logistical support required to meet the first two needs.

Remains of the old main runway at Lavenham, home of the 487th Bomb Group in WWII.

He was soon to become embroiled in a heated controversy over the method the USAAF intended to use in its bombing activity. He and Major General Henry “Hap” Arnold, then head of the U.S. Army Air Forces, were key advocates of daylight bombing, a thing that had been tried by the Royal Air Force and rejected after painfully unsuccessful efforts and their attendant losses.

British doubts about the American daylight bombing approach were publicly expressed on 16 August by Peter Masefield, Air Correspondent of the Sunday Times. Masefield welcomed the prospect of the Americans joining the British in the air war against Germany. He struck out at the B-17 and B-24 though, as being, in his opinion, unsuited for bombing over heavily defended enemy territory: “American heavy bombers—the latest Fortresses and Liberators—are fine flying machines, but not suited for bombing in Europe. Their bombs and bomb loads are small, their armor and armament are not up to the standard now found necessary and their speeds are low.” In that the American bombers were certainly not suited (nor designed) for night bombing, Masefield concluded that the best use to be made of them would be Atlantic anti-submarine and shipping patrols. The next day Hap Arnold read the Masefield column and wired Major General Carl Spaatz for the facts as Spaatz knew them. Timing being everything, Spaatz was, on this occasion, in a position to answer Arnold with an actual combat report for the Rouen mission, and a relatively good one at that.

One British newspaper took the position that “it was a great pity the Americans hadn’t seen fit to build Lancasters, Britain’s finest bomber, and fly them by night instead of clinging to the discredited theory of daylight raids.” Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed, and managed to convince President Roosevelt to halt the daylight bombing. General Eaker wrote: “My most unforgettable meeting with the Prime Minister occurred at the Casablanca Conference. A cable had come to me at my Eighth Air Force headquarters near London, from General H. H. Arnold, Commanding General of U.S. Army Air Forces, directing me to meet him at Casablanca the next day. When I arrived after a night flight and reported to him, I could see at once that he was unusually disturbed and unhappy. There was no vestige of the normal, smiling disposition which had won for him the nickname of ‘Hap’ while a cadet at West Point. He said, ‘Churchill got an agreement from President Roosevelt that your Eighth Air Force will stop daylight bombing and join the RAF in night bombing . . . what do you think of that?’ I said, ‘General, that is absurd; it represents complete disaster. It will permit the Luftwaffe to escape. The cross-Channel operation will then fail. Our planes are not equipped for night bombing; our crews are not trained for it. We’ll lose more planes landing on that fog-shrouded island in darkness than we lose now over German targets. The million men now standing on the ‘Westwall,’ anti-aircraft, fire wardens and bomb repair squads—can now go back to work in the factories or make up another sixty divisions for the Russian front. Every time our bombers show on radars, every workman in the Ruhr takes to the shelters. If our leaders are that stupid, count me out. I don’t want any part of such nonsense.’

The WWII flak tower at Hamburg;

An 8AF shoulder patch;

“When I paused for breath, Arnold said, ‘I know all that as well as you do. As a matter of fact, I hoped you would react that way. The only chance we have to get that disastrous decision reversed is to convince Churchill of its error. I have heard him speak favorably of you. I am going to try to get an appointment for you to see him; stand by and be ready.’

One of the B-17s that flew the first American raid of the European air war, on 17 August 1942.

8AF bomber crewmen synchronize their watches before a mission;

“That evening I was advised that I was to see Mr Churchill at 10:00 a.m. the next day. Shortly after I was admitted to his villa, he came down the stairs, resplendent in his Air Commodore’s uniform. I had been told that when he was receiving a naval person, he wore his Navy uniform—the same for the other services—but this was the first time I had seen him in Royal Air Force uniform. This struck me then as a good omen.

“The P.M. said that he understood from General Arnold that I was very unhappy about his suggestion to our President that my Eighth Air Force join the RAF Bomber Command in night bombing, abandoning the daytime bomber effort. Without awaiting my response, he continued, ‘Young man, I am half American, my mother was a U.S. citizen. The tragic losses of so many of your gallant crews tears my heart. Marshal Harris tells me that his losses average 2 percent while yours are at least double that and sometimes much higher.’

The jubilant crew of Jersey Jinx on their safe return to England after a bombing raid.

“I replied to Churchill that I had learned during the past year, while serving in Britain, that he always heard both sides of any controversy before making a decision and for that reason I wished to present a brief memorandum, less than a page long (it was well known that he seldom read a ‘minute’ of greater length, having it ‘briefed’ instead). This I hoped he would read.

“Mr Churchill motioned me to a seat on a couch beside him and began to read, half aloud, my summary of the reasons why our daylight bombing should continue. At one point, when he came to the line about the advantages of round-the-clock bombing he rolled the words off his tongue as though they were tasty morsels. When he had finished reading the memo, he handed it back and said, ‘Young man, you have not convinced me you are right, but you have persuaded me that you should have further opportunity to prove your contention. How fortuitous it would be if we could, as you say, ‘bomb the devils round the clock.’ When I see your President at lunch today, I shall tell him that I withdraw my suggestion that U.S. bombers join the RAF in night bombing and that I now recommend that our joint effort, day and night bombing, be continued for a time.

“When I reported to General Arnold the result of this meeting, he said, ‘Apparently you accomplished the mission I had in mind. Now I suggest you return to England at once and make sure you prove our case for daylight bombing.’”

Churchill did as he had promised Eaker, and thereafter, found many occasions to refer to “bombing round the clock” until it became a standard expression of the time.

General Eaker and his staff were stationed at RAF Bomber Command Headquarters, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, so they could rub elbows with and learn something of the procedures and methods then in use by the RAF. The Americans were headquartered in what had been a girl’s school before the war years. At war’s end the complex would revert to its former role.

Eaker clearly recognized and valued RAF Bomber Command’s knowledge and experience and set about to take full advantage of their proximity, even though he disagreed entirely with the British position on American daylight bombing. He then patterned the organization of Eighth Bomber Command on that of RAF Bomber Command to ensure maximum cooperation between the two forces. His assignment to England had come when Major General Carl Spaatz, a top commander under Hap Arnold, was given overall charge of the Army Air Force in Great Britain. It was at the suggestion of Spaatz that the American air combat presence in the UK be constructed around the fledgling Eighth Air Force, only recently activated and as yet lacking a mission. Arnold agreed and then Spaatz ordered Eaker to England to get the show on the road. Arnold and Eaker decided that this was their golden opportunity to prove the doctrine of high-altitude daylight precision bombing.

Eaker faced an early and pressing need for airfield and base facilities for the American air combat units that would be arriving in Britain. For some time before the Pearl Harbor attack and the U.S. entry into the war, British and American military officials had been in conversation about arrangements for such units should the United States come into the war at some point, and such accommodation had already been considered. Thus, when the United States did go to war, the Air Ministry could implement a vital, large-scale airfield construction program almost immediately. The Americans were planning an ultimate strength of some 3,500 aircraft based in Britain by April 1943. These included sixty combat groups composed of seventeen heavy, ten medium, and six light bomber; twelve fighter, seven observation, and eight transport groups. Certain airfields in the English Midlands were already under construction for RAF Bomber Command in 1942 and these were quickly turned over to the Americans. As the American air build-up in Britain increased, their airfield requirement was also reassessed and increased, with the majority of the bases and sites allocated for the use of USAAF units in East Anglia.

Another problem requiring Eaker’s urgent attention was that of adequate supply and maintenance capability for his forces in Britain. In addition to the on-going, ever-increasing need of his units for food, clothing, coal, and many other domestic requirements, operationally they needed enormous quantities of aviation and motor fuels, ordnance, spare parts, oil, lubricants and other consumables, as well as the massive inventory of items essential to keep such a dynamic military organization up and running. Here again, the British stepped in to meet the needs of their American cousins, providing both temporary and permanent facilities for depot storage, aircraft repair and maintenance, and technical support.

In line with Eaker’s determination that the Eighth Air Force profit from the experience and learn the procedures of the RAF, it was decided that the Americans must adopt the RAF systems for air traffic control and communications. The British were wholly generous in sharing what they knew about the German enemy, and they provided instructional staffing for the USAAF personnel who were to attend training sessions at special units called Combat Crew Replacement and Training Centres. Primary among these was a new RAF base at Bovingdon, Hertfordshire, and its satellite at Cheddington, Buckinghamshire, which were both near Eaker’s headquarters, and were promptly leased to the Yanks. It was apparent early on that the American crews had, in the urgency to mobilize, been insufficiently trained for the task they were to meet in the coming bombing campaign. This added to the doubt and polite scepticism, impatience and curiosity focused on them and their daylight offensive by the British. Gunners, especially, were found wanting and required additional training. The British, whose early experience with the B-17 Flying Fortress was unsatisfactory in the extreme, had grave misgivings about the equipment to be used by the Yanks.

It was the English weather, however, that proved the greatest challenge to the U.S. crews who had done most of their flying training in the clear, blue skies of Texas and the American west. They were having to learn to cope with the rapidly changing weather conditions in the UK and flying much of the time in poor visibility. The frequently nasty weather of England and the Continent tended to work against their efforts to fly high-altitude precision raids, complicating Ira Eaker’s job considerably.

Getting the first aircraft and crews to the UK was yet another concern of the American general and his staff at High Wycombe. In June the first transport unit to provide logistical support for the Eighth Air Force, the 60th Transport Group, operating C-47s, completed their training and prepared for the move to England. On 18 June the first combat air units of the Eighth were staged to Presque Isle, Maine, to be made ready for their departure east. Their first leg was some 570 miles to Goose Bay, Labrador, and the first fifteen B-17s arrived there in the late afternoon of 26 June, where they were refueled. They left that same evening for Bluie West One, a landing field on southwest Greenland about 775 miles from Goose Bay. At Bluie West One the arriving bombers were unable to land owing to extremely poor visibility and had to elect to either return to Goose Bay or go on to another landing site, Bluie West Eight about 400 miles further along the Greenland coast. One B-17 went on to land safely at BW8, while eleven others returned to Goose Bay. The other three planes became lost and, out of fuel, were eventually forced to crash-land on the Greenland coast. All of the crews survived and were rescued. Additional B-17s, navigating for a large group of P-38 fighters, began the long trip on 19 June and by 27 July, 180 aircraft, B-17s, P-38s, and C-47s, the Eighth’s first major ferrying movement of the war, had arrived at Prestwick, Scotland. In the movement, six P-38s and five B-17s were lost, but all of the crews were saved.

Eighth Fighter Command headquarters, under the command of Brigadier General Frank O’D. Hunter, was established at Bushey Hall, near Watford in Hertfordshire, quite near its counterpart, RAF Fighter Command headquarters at Bentley Priory. Gradually, the important fighter support for the bombers of the Eighth was taking shape.

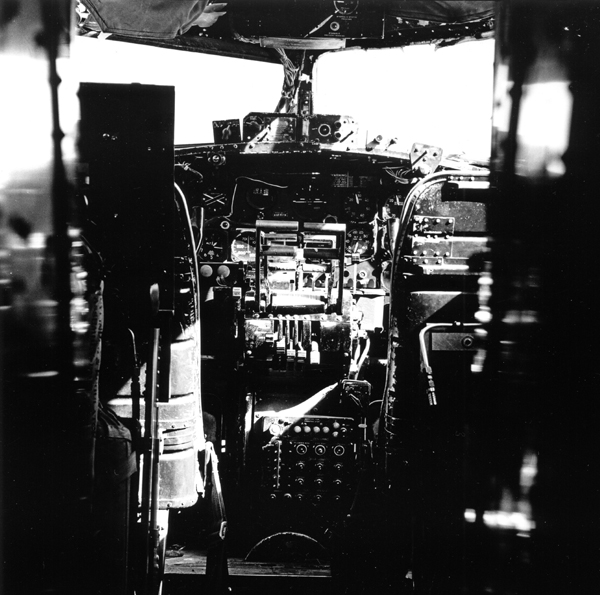

The cockpit of a B-17 bomber with the throttles and propeller controls visible at center.

By the beginning of August 1942 Generals Spaatz and Eaker believed the Eighth was ready for action at last, and soon committed an admittedly tiny force to the Rouen raid, Mission No 1. Getting to 17 August and the actual launch of that first American heavy bomber raid against a German target, had been a test of patience strained nearly to the breaking point for Eaker. Continuing delays in supply and in the arrival of crews and equipment, the wholly inadequate training his crews had received prior to embarking for the UK relative to the realities of the air war with the German enemy, and the often poor weather, mitigated against his determined effort to bring the new air force into the war.

General Spaatz had decided early in the Eighth’s UK tenure that it was more important to bring the first heavy bomber crews and equipment to England as soon as they were organized, equipped, and trained well enough to negotiate the ferry route, than to give them the more thorough training Stateside that they would so desperately need. Tight formation and high-altitude flying was all but completely missing from the repertoire of his first bomber pilots and co-pilot to arrive. Many of the radio operators were unable to either send or receive Morse code. And the previously mentioned deficiencies of most of the arriving gunners were, perhaps, most worrying of all. Those in the top echelon of the Eighth were convinced that the only way the bombers could hit and destroy enemy targets by daylight without suffering prohibitive losses was through being able to defend themselves effectively against the enemy fighters.

USAAF cooks at work on an 8AF base in WW2 England;

A Flying Control officer on duty at the 44th Bomb Group’s Shipdham base;

The painted leather A2 flying jacket of Sidney Rapaport.

clockwise from top left: Postwar views of RAF Hemswell and the USAAF bases at Deenethorpe, Podington, Grafton Underwood, Rattlesden, and Bury St Edmunds.

Carl Spaatz stood on the roof of the flying control tower at Grafton Underwood with several Eighth Air Force and RAF staff officers and approximately thirty members of the U.S. and British press. They had gathered to watch the take-off of the twelve American bombers of the 97th Bomb Group, the first and only heavy bomb group of the brand new Eighth U.S. Army Air Force. The first raid was vitally important to Spaatz, Eaker, and to Hap Arnold back in Washington—all of whom were betting the whole kitty on the concept of daylight bombing in the manner they intended to practice it. After months of frustrating delays, set-backs, and the scepticism of the British and American publics and nearly everyone else involved in the war against the Germans, their duty and opportunity to get into the fight and show what they could do had finally come.

All twelve B-17s were airborne from Grafton by 3:40 that afternoon, as were six more from the base at Polebrook, Northamptonshire. The Polebrook planes were to act as a diversion for the main force.

“When the mission has gone the ground crews stand about looking lonesome. They have watched every bit of the take-off and now they are left to sweat out the day until the ships come home. It is hard to set down the relation of the ground crew to the air crew, but there is something very close between them. The ground crew will be nervous and anxious until the ships come home. And if the Mary Ruth should fail to return they will go into a kind of sullen, wordless mourning. They have been working all night. Now they pile on a tractor to ride back to the hangar to get a cup of coffee in the mess hall. In the barracks it is very quiet; the beds are unmade, their blankets hanging over the sides of the iron bunks. The pin-up girls look a little haggard in their sequin gowns. The family pictures are on the tops of the steel lockers. A clock ticking sounds strident.”

—from Once There Was A War by John Steinbeck

Ira Eaker was riding in Yankee Doodle, the lead ship of the second flight of six bombers, to see for himself how this first mission would go.

The Rouen target was important to the Germans because of its major repair shops and large locomotive depot, as well as the many hundreds of freight cars there and the links it provided to the Channel ports and the west of France. The aiming points for the bombers were the locomotive workshops and the Buddicum rolling stock repair shops.

The RAF, for its part, contributed a great many Spitfires to provide close air support for the B-17s—four squadrons of Mk IXs going with the bombers to the target, and five squadrons of Mk Vs for withdrawal support.

The weather cooperated too with excellent visibility for the attacking force, and all twelve planes dropped their loads of general purpose bombs, 36,900 pounds, from an altitude of 23,000 feet. Official records indicate reasonably accurate bombing with approximately half the bombs falling in the general target area. Results were surprisingly good for a small, inexperienced force, with direct hits on two large trans-shipment sheds in the heart of the marshaling yards, with significant track damage, and the destruction, damaging or derailing of quite a lot of rolling stock. There was one direct hit on the locomotive workshop. In all, however, the damage caused was—while sizable—not sufficient to seriously impair rail operations there. Clearly a much larger bombing effort would be needed to take out the Sotteville yard.

A post-mission meal for weary American airmen.

A B-17 gunner with his aircraft at Bassingbourn.

Neither the attacking or diversionary forces suffered any losses and they incurred only minimal damage. The Germans were barely responsive to the attacking forces with only slight flak damage to two aircraft. The Luftwaffe did respond with an attack by three Me 109 fighters with no damage resulting. There were no injuries to the bomber crews apart from the bombardier and navigator of one plane who were slightly injured when the plexiglas nose of their B-17 shattered in a bird strike on the return flight to England.

In a letter to General Spaatz on 19 August 1942 Ira Eaker observed that the crews on this initial American raid were alert and enthusiastic, but nonchalant to the point of being blasé. They needed more drill in the use of oxygen equipment and, in general, better discipline. The formations needed tightening for improved defense against enemy fighters. Other items requiring considerable immediate attention included the timing of the rendezvous with fighter escort, navigation, bombing training, and gunnery. Pilotage needed a lot of work with the aim of refining formation flying to the point where tight and maneuverable formations could be flown with the shortest possible level bomb run on a target, thus minimizing exposure to enemy flak and fighter opposition. As to the ability of the bombers to defend themselves against enemy fighters, it was too soon to know. Certainly the Rouen raid had not provided any meaningful test of that, and both Spaatz and Eaker determined to tread with utmost caution in committing their bombers to subsequent missions that required much deeper penetration into German-occupied territory.

“For us the war was very new. The word was that the average life expectancy for a tail gunner in combat was thirty seconds. All kinds of rumors were floating around. England was very different from the United States. It had already suffered three years of war, but the people were very friendly and helpful. We had to get used to a different monetary system, and I found out that Brussels sprouts and some of the other food they gave us were not the best things to eat when you were going to fly at high altitude in an unpressurized airplane. I bought a bike and, though I didn’t get off the base as much as some of the guys, I really enjoyed myself when I did. I had a 36-hour pass in London and had a cab driver take me for a tour. I liked the scotch, but could never get used to the dark warm beer. England has the most beautiful countryside to fly over. We did a lot of that.”

—Ed Leary, 97th Bomb Group (H), Eighth USAAF

On 18 August General Eaker received the following message from Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, RAF Bomber Command: “Congratulations from all ranks of Bomber Command on the highly successful completion of the first all-American raid by the big fellows on German-occupied territory in Europe. Yankee Doodle certainly went to town and can stick yet another well-derved feather in his cap.” To paraphrase Mr Churchill, for General Eaker and his staff, it was, perhaps, the end of the beginning.

“A journalist will say anything to earn a fast buck. I get my information from the horse’s mouth, not from the rear end where they do.”

—Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Harris

“We walked toward the ship through nacreous pools of oily water on the asphault parking area. Visibility was less than a hundred yards. We couldn’t begin to see Erector Set and Finah Than Dinah, the Forts that were parked on hardstands on either side of ours on the perimeter. It was stations time, a quarter to ten, and we went into The Body. The pearly ground fog had lifted; low clouds were running down to the eastward like suds in a rocky river bed. From my seat in the cockpit I could see the cubical control tower in the far distance, and I could even make out some tiny figures—members of the operational staff—on the iron-railed balcony of the tower. Eight or ten Forts were visible, scattered at their hardstands along the perimeter track, dark and squat, imponderable, rooted to the ground by their tail wheels. A big camouflaged RAF gasoline lorry and trailer moved slowly along the main road toward the hangars. Jeeps busy-bodied up and down the perimeter track.”

—from The War Lover by John Hersey

“Presently he turned off on a side road, propped his bike against a hedge and strode slowly a hundred yards out onto an enormous flat, unobstructed field. When he halted he was standing at the head of a wide dilapidated avenue of concrete, which stretched in front of him with gentle undulations for a mile and a half. A herd of cows nibbling at the tall grass which had grown up through the cracks, helped to camouflage his recollection of the huge runway. He noted the black streaks left by tires, where they had struck the surface, smoking, and nearby, through the weeds which nearly covered it, he could still see the stains left by puddles of grease and black oil on one of the hardstands evenly spaced around the five-mile circumference of the perimeter track, like teeth on a ring gear. And in the background he could make out a forlorn dark green control tower, surmounted by a tattered gray windsock and behind it two empty hangars, a shoe box of a water tank on high stilts and an ugly cluster of squat Nissen huts.”

—from Twelve O’Clock High by Beirne Lay Jr and Sy Bartlett

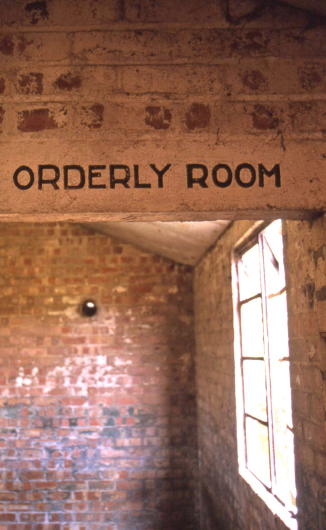

The Orderly or Day Room at Deenethorpe, home to the 401st Bomb Group in World War II.

Most USAAF personnel got around their large air bases by bicycle. This is the Ridgewell base of the 381st Bomb Group, Eighth Air Force.