Among the best aircraft of the Second World War is the Avro Lancaster bomber, and this example is being serviced at its hardstand on an air station somewhere in wartime England. 7,377 Lancasters were produced. It entered service with the Royal Air Force early in 1942.

The delta-winged Avro Vulcan bomber was the mainstay of the RAF airborne strategic nuclear deterrent through much of the Cold War.

“As they watched it the bomber seemed to swell up very gently with a soft whoomph that was audible far across the sky. It became a ball of burning petrol, oil and pyrotechnic compounds. The yellow datum marker, which should have marked the approach to Krefeld, burned brightly as it fell away, leaving thin trails of sparks. The fireball changed from red to light pink as its rising temperature enabled it to devour new substances from hydraulic fluid and human fat to engine components of manganese, vanadium, and copper. Finally even the airframe burned. Ten tons of magnesium alloy flared with a strange greenish blue light. It lit up the countryside beneath it like a slow flash of lightning and was gone. For a moment a cloud of dust illuminated by the searchlights floated in the sky and then even that disappeared.”

—from Bomber by Len Deighton

“Night bombing towards the end of 1916 and early 1917 was carried out mainly with Sopwith Strutters in which the rear seat was removed to accommodate a honeycomb bomb rack taking twelve French Le Pecq liquid twenty-pound bombs. The two old twin Anzani-engined Caudron G IVs were also used and they carried an observer or bomb aimer as well as a pilot. One took off down a paraffin flare path usually about two hours before dawn and on return waited until sufficient light enabled one to see the ground clearly before landing. Our usual night targets were the docks and shipping at Ostend, the docks and submarine pens at Bruges, and the Mole and shipping alongside at Zeebrugge. All three were heavily defended by AA and rocket batteries and bristled with searchlights, while more searchlights were spaced along the coast right up to the Dutch frontier, especially at Westende, Middlekerke, Wenduyne and Blankenberghe.

“A truly wonderful fireworks display attended us on our night stunts, the long chains of vivid jade-green balls which streaked up, invariably reaching one’s height before falling away and dying out, were a magnificent sight providing they didn’t come too near. They must have been in the nature of a rangefinder as they always seemed to come to, or slightly above one’s level, whatever one’s height, before fading out, and were immediately followed by HE bursts pretty well on target. We called them ‘Flaming Onions’ and at first imagined they were connected by wire which would entangle one’s propeller; but of course they were not, their regular spacing, like a glorious jade-green necklace, being due to some sort of machine mortar from which they were fired. I never heard of their doing any damage but occasionally one fell on a wing, being quickly swept off by the airspeed and slipstream, the fabric only showing a slight scorching, but I wouldn’t have welcomed one in the cockpit. The advantage of coastal targets was that one could creep up the coast two or three miles out to sea without being heard, then turn in when approximately level with the objective, so giving the defenses very little warning of one’s approach. If one was heard the signal went up from Nieuport and was repeated all the way up the coast, on came the searchlights and the guns were ready for you.”

—from Bomber Pilot 1916-1918 by

C. P. O. Bartlett

During the winter of 1916, the Germans decided that, as their airship raids over London had become impossible to sustain, they should launch a campaign of bombing attacks by airplane against the British. Their new strategic battle squadron 3, Englandgeschwader, was assigned the long-range attacks on British war industry, coast ports, transport, and communications. The squadron was equipped with Gotha G-series bombers powered by two 260 hp Mercedes six-cylinder in-line engines. For the time, the Gotha operated in relative safety from attack by British fighters, as it bombed from an altitude of 16,000 feet and was then able to climb even higher for its return trip to base. On 13 June 1917, in a bold daylight attack on the heart of the British capital, a force of fourteen Gothas dropped a total of seventy-two bombs on the area of Liverpool Street Station in London, killing 162 people and causing a profound psychological reaction among the populace and a heated debate on the organization of the home defense. All of the attacking force returned safely to their base at Gontrode in Belgium. By October, however, the British defenses got the better of the Gothas, with much-improved anti-aircraft and fighter opposition, and the Germans switched to night bombing. This offensive included a few significant incendiary raids, the beginning of a planned campaign of fire raids which was called off shortly before negotiations to end World War I began. The psychological effect on Britons by the Gotha offensives remained after the end of the war. Fearful memories of being bombed from the air were to be long-lasting.

It fell upon its victims while emitting a terrifying shriek. An icon of the Nazi Blitzkrieg, it typified the “lightning strike” of the hard-charging German forces at the beginning of World War II. All across Poland, Czechoslovakia, the Low Countries and France, the siren scream of the Ju 87 Stuka announced the imminent arrival of Hitler’s legions. The dive-bombing of the Stuka was as much psychological warfare as anything else.

The Stuka’s command of the skies was relatively short-lived, however. The Hurricanes and Spitfires of the Royal Air Force saw to that rather quickly and without much fuss. It was no match for the Merlin-engined fighters and fell to them in great numbers throughout the summer and fall of 1940. While it was still to perform with some distinction against Allied shipping in the Mediterranean and their convoys sailing the arctic route to Russia, in the Balkans and against Crete, it was no longer the threat it had once been.

The name Stuka came from the German term Sturzkampfflugzeug, referring to dive-bombers. The Germans were fascinated with the concept and potential of aerial dive-bombing as early as the late 1920s, and in the Ju 87 they produced a rugged, if somewhat ugly and slow two-man machine, capable of terrifying the folks below in the target area while doing damage as well.

The plane was significantly improved through the development and production of several later marks, making it formidable to Germany’s opponents right up to the summer of 1940 when reality struck in the form of RAF Fighter Command and the heyday of the Stuka was over.

The Bristol Blenheim was a pioneering effort in the British aircraft industry; the first all-metal, stressed-skin, cantilever monoplane bomber. It gave the Royal Air Force just the edge it needed, and brought an end to the older, prevailing philosophy about bomber aircraft design. It was a bomber of the 1930s capable of outpacing most fighters of the day.

The Blenheim had its detractors, and was certainly not one of aviation’s greatest achievements, but in its time it met a need of the RAF and, in a sense, kept them in the game until the bigger, better, more capable bomber types came on stream.

Powered by two Bristol Mercury XV air-cooled radial engines rated at 995 hp each, the Mk IV Blenheim was the best of the breed. It cruised at 259 mph at 15,000 feet with a normal cruising speed of 198 mph and it carried a normal bomb load of 1,000 pounds.

The Blenheim was widely used and performed commendably, and while it was not particularly outstanding among all the bomber aircraft of the war, it did represent an important transition for RAF Bomber Command.

The Vickers Wellington carried the brunt of RAF Bomber Command’s night bombing offensive against German-occupied Europe in World War II until the coming of the new heavy bombers. Known affectionately as the Wimpy, after the character J. Wellington Wimpy in the Popeye comic strip, it served effectively throughout the war. Much of its success was due to its geodesic construction, a revolutionary “basket weave” structure employed by the design engineer Barnes Wallis, who also designed the “bouncing bombs” used in the Dam Busters attack of May 1943. This construction technique resulted in an amazing combination of high strength and low weight, and an airplane able to take terrific battle damage and still bring its crew home safely.

The Wellington B Mk X had two Bristol Hercules VI radial engines rated at 1,585 hp for take-off, a cruising speed of 180 mph and a service ceiling of 24,000 feet. Its range, with a 4,500-pound bomb load was 1,325 miles.

While a solid performer, the Wellington also demonstrated conclusively to the British Air Staff the futility of daylight bombing raids without fighter escort when the enemy had obvious air superiority. At one point, two raids cost the RAF twenty-one Wellingtons of a total force of thirty-six despatched. From that day the daylight bombing campaign of the RAF was abandoned.

They sounded odd . . . out of sync, the Daimler Benz DB 601 (and later the Junkers Jumo) engines of the Heinkel He 111s that visited London and other English cities on so many nights during the great Blitzes of 1940-41, and after in World War II. The He 111 had good flying characteristics and was presented to the German public initially in early 1936 in the form of a ten-passenger commercial airliner. It was clear to aviation experts, however, that this was a mean machine intended for a far more aggressive role than that being conducted by Deutsche Lufthansa.

This relatively light and fast medium bomber cruised at 224 mph at 16,400 feet and had a service ceiling of 25,500 feet, but a range, with a maximum bomb load, of only 760 miles.

The 111 broke its maiden in the skies over Spain with the bomber element of the German Air Force’s Condor Legion in 1936 and, though lightly armed with only three 7.9mm machine-guns, was quite effective and suffered only negligible losses in the Spanish Civil War. Daylight bombing, however, always a tricky prospect for any air force, proved too much for the Heinkel when it ran into the Spitfires and Hurricanes of the RAF in the Battle of Britain. It was undergunned and not really fast enough to put up much of a struggle against the excellence of the British fighters and their extraordinarily courageous pilots who had the added incentive of defending their island against Nazi invasion. The Germans scrambled to improve the armament of the 111 but, by the final phase of the Battle, were forced to withdraw the bomber from day raids and put it on the night shift.

A Consolidated B-24J Liberator bomber in wartime England..

In the mid-morning of 3 February 1940, a Heinkel He 111 had the dubious distinction of being the first German warplane to fall on English soil in World War II. The bomber was under the command of pilot Hermann Wilms and carried a crew of four, all Unteroffiziere: Peter Leushake, Johann Meyer, and Karl Missy. Their airplane, No 3232, was operating with 2nd Gruppe, KG 26 “lion” Geschwader from Schleswig-Jagel, a base north of Hamburg. Their assignment that frigid winter morning was to attack an enemy convoy off the northeast coast of England. Shortly after 9:00 a.m., Blue Section of No 43 Squadron, RAF, got the call at Acklington and in a few minutes Flight Lieutenant Peter Townsend and Sergeants “Tiger” Folkes and Jim Hallowes were climbing to intercept the hapless Heinkels. Their Hurricanes joined with the German planes of the Schleswig flight and Wilms’ bomber was badly shot up by Townsend. It crash-landed near Whitby.

The front-line heavy bomber of the Japanese Army Air Force for most of World War II was the Mitsubishi Type 97 Ki.21-11b, known to the Allies as the Sally. Dating from 1937, it was a twin-engined aircraft with a 236 mph cruising speed at 16,400 feet and a top speed of 297 mph at 13,000 feet. It had a 1,350-mile range with a maximum bomb load of 2,200 pounds. Its power was provided by two Mitsubishi Ha.101 Type 100 radial engines rated at 1,490 hp each. The Ki.21 as operated by a four-man crew: a pilot, co-pilot/navigator, radio operator/gunner, and a bombardier/gunner.

Initial combat operations for the Ki.21 came in August 1938 when the first units to receive the aircraft, the 60th and 61st Sentai, began flying it in Manchuria against the Chinese, where it showed that it was not up to the task at hand. It was being flown to its objectives without escort, and, with insufficient defensive armament, could not adequately defend itself and suffered alarmingly high losses in this, its first trial by fire.

The much-maligned Martin B-26 Marauder medium bomber (Martin Murderer, One-a-day-in Tampa Bay, etc.) ultimately proved to be a good airplane with a fine safety record.

Subsequent models of the bomber, produced with features such as improved fuel tanks, increased armament and enlarged flaps, replaced the older, inferior model in early 1941, giving a new, but unwarranted sense of confidence and security to the crews who flew it. This confidence was soon dispelled when they encountered fighter opposition from the P-40s of General Claire Chennault’s American Volunteer Group, the Flying Tigers, and RAF Hurricanes. In an engagement with the AVG and the RAF on 20 December 1941 over Kunming, the Japanese lost twenty of their attacking force of sixty bombers.

After the fall of Singapore in mid-February 1942, Japanese units flying the latest version of the Sally were assigned to hit British and Canadian garrisons at Hong Kong, which they did very well, albeit with no enemy fighter opposition.

With the increasing presence of U.S. and British high performance fighters in the western Pacific, Sally losses rose sharply and its days in the region were numbered. The Sally was thought to be a comparatively easy target by Allied fighter pilots, with its inadequate defensive armament. The bomber fared no better in the China-Burma-India theatre of the war where, despite operating with significant fighter protection, its losses continued to climb. A pattern began in which the Sally was withdrawn from front-line units until, finally, its role was reduced to transport and suicide attack.

Widow-Maker, Flying Torpedo, Flying Prostitute, Martin Murderer, and One-A-Day-In-Tampa Bay—were all references to the B-26 Marauder medium bomber. It had a reputation among American pilots learning to handle it. U.S. Government investigators convened on four separate occasions to consider discontinuing its development. The unusually small wing area and the resultant high wing-loading led to the Marauder’s bad name. Ultimately, though, it rose above it all and, by 1944, the U.S. Ninth Air Force was operating Marauders in the European theatre with a lower operational loss rate than that of any other American aircraft type.

With a 1,100-mile range at maximum cruising speed, a 283 mph top speed at maximum weight, and a service ceiling of 19,800 feet, the Martin bomber was not the most impressive of performers, but it got the job done. It began to make a name for itself beginning with the run-up to D-Day when it was the first USAAF aircraft in the European theatre to operate at night. Its ability to hit and destroy bridges and other targets requiring a high degree of precision was exceptional. The B-26 flew more than 29,000 sorties in its first year of combat in Europe, dropping 46,430 tons of bombs and incurring a relatively tiny loss rate for the effort. 5,157 Marauders were made at Martin by the end of the war and, despite the views of its early detractors, it was in fact a good and reliable airplane, if one that demanded pilots of a high standard.

Among the most interesting and successful of all bombing aircraft is the De Havilland Mosquito, whose designers believed that the airplane could accomplish its mission and defend itself primarily by relying on its great speed to outrun enemy fighter opposition. They were correct, as if more proof were needed of the adage that “an airplane that looks right will fly right,” the Mosquito was as graceful and elegant of line as she was swift, powerful, and a joy to fly. Her secrets were: a small, highly practical airframe, a wonderful aerodynamic aesthetic, an amazingly high power-to-weight ratio, and energy from two superb and reliable Rolls-Royce Merlin engines.

The De Havilland design team was working on a high-speed bomber concept as early as October 1938. When war broke out in September 1939, the British Air Ministry began to show serious interest in the idea of a bomber capable of “fighter” speeds. It asked De Havilland if they could come up with a design for such an aircraft, that could carry a 1,000-pound bomb load and have a range of 1,500 miles. The manufacturer agreed to have a go and was given latitude to take a revolutionary approach to the problem. The Air Ministry was thinking “unarmed” high-speed bomber, but the airplane maker had other ideas and proceeded to design an aircraft with provision for guns or cameras, as well as bomb-carrying capability, with an eye to making their new bird a model of versatility as well as one of supreme performance. It would, they thought, be as competent in the photo reconnaissance or fighter roles as it would in the bomber role. Not only would it be the fastest bomber in the world, and brilliant in its other capacities, it would be made of WOOD. The designers incorporated the timely advantages of a new process for fabricating the plane from wood laminates, and when it was finished, the “wooden wonder” as the Mosquito was often referred to, was indeed a 400 mph airplane that cruised at well over 300 mph, climbed to 15,000 feet in less than eight minutes, had a service ceiling of 37,000 feet and a range (with a 4,000-pound bomb load) of 1,370 miles at 245 mph. As a bomber, the Mossie normally went to its target at an economical cruising speed of 300 mph at about 22,000 feet or down around sea level at a similar speed.

Brand new Boeing B-17G aircraft on an air depot field in England awaiting delivery to the bomb groups of the Eighth Air Force;

The airplane was extremely successful in a wide range of activities, not least being the vital Pathfinder role later in the war. The outstanding performance and legendary combat record of the Mosquito assure its place among the great planes of all time.

The North American B-25 Mitchell provided a great psychological boost to the American people, inspiring them and raising their spirits at a point in the Second World War that was desperately needed. In April 1942, Colonel Jimmy Doolittle led a small force of sixteen B-25s from the deck of the carrier Hornet to bomb Tokyo, Kobe, Yokohama, and Nagoya, Japan, in the first U.S. retaliation for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the previous December 7th. The raid caused little significant damage, but showed the enemy that it was definitely vulnerable to American air strikes. Named for the U.S. Army bombing pioneer, Billy Mitchell, it was an excellent and highly efficient performer, able to deliver a 3,200-pound bomb load over a range of 1,275 miles at 200 mph. It served in most WWII operational theatres.

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress, successor to the B-17 and the backbone of the American campaign in the Pacific against Japan.

The Vickers Wellington medium bomber employed geodesic design developed by the famous design engineer Barnes Wallis.

The Douglas A-1 Skyraider came into service in 1946, too late for World War II but in time for the Korean conflict. Many consider it the most unique, sophisticated and utilitarian single piston-engine combat plane in history. Capable of carrying a load of bombs heavier than its own empty weight, the Skyraider was used extensively in Korea, and in Vietnam by the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Navy and Marines, and by the South Vietnamese Air Force. Known in that war as Sandy or Spad, the A-1 was produced in a quantity of 3,180 by 1957 when its assembly line closed. The big plane had a top speed of 318 mph and an operational range of 3,000 miles and was armed with four 20mm wing-mounted cannon. Its engine power came from a Wright

R-3350 2,700 hp radial engine. Capability, versatility, and endurance summed up the virtues of the impressive Douglas bomber.

The Short Stirling of WWII might have been a much better bomber had it not been for the short-sighted approach of those Air Ministry types who specified it in the mid-1930s. They insisted on a 100-foot wingspan to fit the opening of the then-standard RAF hangar doors. That requirement doomed the plane to a second-rate career, operating lower and slower with less ability to climb and to survive flak damage than its superior heavy-weight cousins, the Halifax and Lancaster.

Indicative of the Stirling’s shortcomings was the position it had to accept when flying on large-scale raids in company with Lancasters and Halifaxes. Those other heavies were going to the target at 18,000 to 20,000 feet, while the fully-loaded Stirlings were unable to climb much higher than 12,000. As the war went on, the Stirling was ultimately relegated to lesser roles including raids on fringe targets, supply drops to partisans in enemy-occupied Europe, mine-laying, transport, and glider-towing. In these roles it performed admirably.

In 1940, British Ministry of Aircraft Production was keen to convert the Avro and Vickers production lines from the assembly of the less than impressive twin-engine Manchester bomber to assembly of additional Handley-Page Halifax heavy bombers. But Avro chief designer Roy Chadwick argued forcefully that his new Manchester III four-engine bomber was not only superior to the Halifax; it could be made on the existing Manchester production line without the delays inherent in converting to the Halifax manufacture. He won the argument and, by 1945, some fifty squadrons of the resulting Lancaster heavy bomber were operational.

The Lancaster was the backbone of the famous “thousand bomber raids” and, in August 1942, the elité new 8 Group Pathfinder Force was launched with Lancasters of No 83 Squadron. Using the navigational aid “Gee,” the Pathfinders went to the targets ahead of the main bomber force and marked the aiming points using flares and incendiaries to ease the task of the bombers bringing the high explosives.

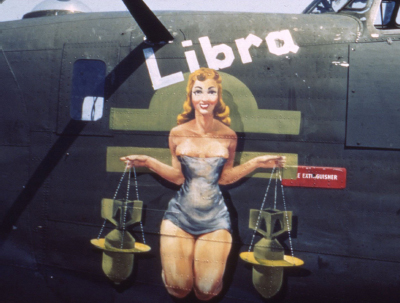

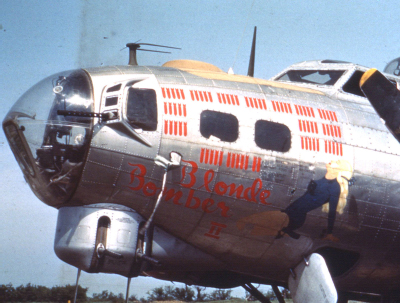

Eighth Air Force heavy bomber nose art examples.

Most Lancasters were powered by four 1,460 hp Rolls-Royce or Packard-built Merlin XX engines. They were operated by a crew of seven and weighed as much as 72,000 pounds all-up with the maximum bomb load. As such they had a maximum speed of 287 mph and a cruising speed of 210 mph at 12,000 feet and a range of 1,660 miles. Their .303 machine-guns were ultimately replaced with the more potent .50 calibre Browning machine-guns. A total of 7,377 Lancasters were built.

At the end of the war Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Harris wrote to the Avro Production Group: “As the user of the Lancaster during the last 3 years of bitter, unrelenting warfare, I would say this to those who placed that shining sword in our hands; without your genius and your effort we would not have prevailed—the Lancaster was the greatest single factor in winning the war.”

The Boeing B-17 was made for high-altitude daylight precision bombing and, in most respects, performed superbly. The B-17 made a powerful impression on the German war effort. It also contributed greatly to the defeat of the German Air Force both in the air and on the ground. Of the models produced, the G was the most effective, and 4,035 Gs were built by mid-1945, with Boeing, Douglas, and Vega all producing them. At the peak of its utilization, nearly 4,600 B-17s of various marks were in the active USAAF inventory.

The maximum bomb-carrying capacity of both the principal American heavy bombers of WWII, the B-17 and B-24, was considerably less than that of the British Lancaster. Both of the American bombers were designed with crew protection and defensive firepower as primary considerations. Both required a crew of ten men and were fitted with substantial armament and armor. They were mounted with as many as thirteen .50 calibre machine-guns and their ammunition. All of this extra weight resulted in a hefty bomb-load penalty. However, the Americans believed strongly in the concept of daylight precision bombing. They felt that they could hurt the enemy more through the surgical placement of fewer bombs on key industrial, supply, and resource targets than the RAF could through its campaign of nighttime area bombing.

Which service was right? Both were, to the extent that the Allied strategic bombing “round-the-clock” campaign helped to bring about the defeat of Germany in the war.

As the American General Curtis LeMay, a brilliant combat leader in the U.S. strategic bombing campaigns against both Germany and Japan, put it: “The Air Force kind of grew up with the B-17. It was as tough an airplane as was ever built. It was a good, honest plane to fly—a pilot’s airplane. It did everything we asked it to do and did it well.”

Probably it is fair to say of the B-17 and Lancaster crews that each thought their airplane was the finest, safest, most reliable bomber then flying. Certainly, few of them would have traded places with their British or American counterparts. Most would probably agree that the Flying Fortress and the Lancaster are the most admired . . . and the classic bomber aircraft of all time.

Designed for a 1936 Air Ministry requirement, the Short Stirling was the first RAF four-engine bomber of the Second World War.

She was like the less attractive sister of the beauty queen—the chunky, slab-sided B-24 was the product of General Hap Arnold’s request of the Consolidated Aircraft Company to design a new bomber that would have better performance than the

B-17. It was January 1939; war clouds loomed and Arnold wanted a bomber with a maximum speed of 300 mph, a ceiling of 35,000 feet, and a range of 3,000 miles. The B-24 Liberator lacked the grace and glamor of the B-17 Flying Fortress, but she performed brilliantly on more operational war fronts for a longer period and with greater versatility than her sister ship.

The B-24 did slightly out-perform the B-17. She had a maximum speed of 300 mph at 30,000 feet and a range of 1,700 miles with a 5,000-pound bomb load at 25,000 feet. Her power came from four 1,200 hp Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasp radial engines.

Of all the famous missions flown by B-24s, probably the most controversial and horrendous was the Ploesti oilfield raid of 1 August 1943. 177 Liberators were sent that day on a low-level attack against the Astra Romana, Columbia Aquila, Steaue Romana, and Romana Americana oil complexes. One hundred and sixty-three made it to the target and delivered their bombs. The bombing did a lot of damage, but the attacking force paid dearly with the loss of fifty-four bombers and 144 crewmen.

By the end of the war, 18,188 Liberators had been built. They served with the U.S. Army Air Forces, the Royal Air Force, the U.S. Navy, the Royal Australian Air Force, the South African Air Force, and later with the Indian Air Force.

Like the Liberator, the Handley-Page Halifax bomber was less lovely than its RAF counterpart, the Lancaster, but more versatile and a powerful, effective workhorse, as a bomber, a maritime reconnaissance aircraft, a freighter, a glider tug, an air ambulance, and a personal transport. The Halifax shared the major responsibility for RAF Bomber Command’s night-bombing offensive against German targets across Europe. Some 40 percent of the heavy bombers built in the UK during the war were Halifaxes. They operated with distinction against Germany, throughout Europe and in the Far East and the Middle East, as well as serving in the airborne operations over Normandy, Arnhem, and the Rhine crossing. 6,176 Halifaxes were produced through 1946.

The primary partner of the Avro Lancaster in the strategic bombing campaign against Nazi Germany in WWII, the Handley Page Halifax performed with distinction throughout the conflict.

The successor to the B-17 Flying Fortress was the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, a bomber with a top speed of 357 mph at 30,000 feet, a cruising speed of 220 mph at 25,000 feet, and a range with a 10,000-pound bomb load of 3,250 miles. The B-29 operated mainly in the Pacific theatre with most of them being based initially in the Marianas Islands. They also operated from bases in China and India.

Referred to as “Mister B” by the Japanese, the B-29s began their bombing campaign against targets on the home islands of Japan in November 1944 with raids on the Nakajima Aircraft factories at Musashino near Tokyo.

On 20 January 1945, General Curtis LeMay took charge of the 20th Bomber Command and immediately began a program of reorganization and redirection of its resources. He went with his B-29s on some of the missions to Japan, mainly conventional high-altitude precision daylight strikes. But he ordered a few experimental “fire raids” using incendiary ordnance instead of high explosives. These raids were inspired by his experiences with the Eighth Air Force and the firestorm attacks on Hamburg. The results of the Japanese fire raids led to new targeting priorities for his Superforts: aircraft engine factories, cities, and aircraft assembly plants. The city targets were to be attacked with incendiaries and approximately sixty Japanese cities were earmarked for such attention.

The elegant and impressive De Havilland Mosquito.

LeMay knew of the problems faced by his crews in the high-altitude raids on Japan: jet-stream winds of extreme velocity, frequent heavy cloud cover over the targets, inconsistent engine performance and reliability issues (“three turning, one burning” was a common reference to the B-29s at the time), inability to carry the required bomb load, strong and determined, fighter opposition, and heavy exposure to enemy flak. He directed that the bombers would henceforth fly the incendiary fire raids at low level by night. He believed the engines would run cooler, use less fuel and would last longer. He had them fly in a bomber stream rather than a formation, to save more fuel. There was little genuine threat from Japanese night fighters, thus reducing the need for defensive firepower on the B-29s. He had all guns but the tail turret stripped out of the bombers, eliminating excess turrets, guns, ammunition, and gunners; the weight saving translating into additional bomb tonnage carried.

Along with all the other changes, LeMay had Pathfinder B-29s fly out ahead of the main force to set massive fires on which the rest of the bombers would drop their loads. The first of his great fire raids took place on 9 March 1945. It was the single most destructive air raid in history, including Dresden, Hamburg, and both atomic attacks. Twenty-five percent of all the buildings in Tokyo were destroyed. One hundred and fifty thousand inhabitants were killed, injured, or missing. One million citizens were made homeless.

In that time many structures in Japan were made of cedar, bamboo, and paper, materials that burned well, and in the course of many fire attacks made by the B-29s, most of the country’s cities and towns were turned to ash. The fire raids continued into August 1945 with increasing ferocity.

In June, the first B-29s to occupy the giant new base at North Field, on the island of Tinian arrived. On 6 and 9 August, two of the new atomic bombs were dropped by B-29s of the 509th Composite Group on Hiroshima and Nagasaki respectively, leading to the unconditional surrender of Japan to the Allies on 14 August.

The Convair B-36 Peacemaker was aptly nicknamed. For the ten years in which she roamed the world’s skies, peace reigned, for the most part. Big in every respect—47 feet high, 162 feet long, with a wingspan of 230 feet, she dwarfed the size of a modern 747 jumbo jet airliner. Able to cruise at 230 mph with a service ceiling of 45,700 feet, the B-36 had a top speed of 435 mph. When full of fuel, bombs, ammunition, and her sixteen-man crew, she weighed more than 205 tons and could range 10,000 miles, staying aloft for more than two days while carrying forty-three tons of conventional or nuclear bombs. She was armed with sixteen 20mm cannon and driven by the power of six enormous Pratt and Whitney R-4360 pusher-type piston engines mounted on the trailing edge of her wing with each producing 3,800 hp, and four General Electric J47 jet engines of 5,200 pounds thrust each in twin wing-mounted pods.

Coffee in the Officers’ Club at the 381st Bomb Group base, Ridgewell in Essex.

Such was the enormity of the noise and vibration she generated that, when approaching at low altitude in her landing pattern over a city, she announced her presence as much as a full minute before coming into view. The earth literally shook when a B-36 was in the neighborhood. In San Diego where more than a hundred of the big planes were modified during the 1950s, engineering test flights were conducted frequently. Windows rattled and cars waiting at a traffic light at an intersection near the end of the Lindbergh Field runway were often “nudged” where they sat if one of the bombers was having its engines run up prior to take-off.

More than 380 B-36s were built by Convair at Fort Worth, Texas, by August 1954 and the end of production. The B-36 never saw combat—a tribute to her role as a peace keeper.

They were the V-force, Britain’s bomber delivery system for her Cold War nuclear capability. The Vickers Valiant, the Handley-Page Victor, and the Avro Vulcan formed the sharp end of a powerful deterrent force that served effectively into the early 1970s.

Avro chief designer Roy Chadwick’s superb delta-wing Vulcan bomber began RAF service in 1956. Operated by a five-man crew, the Olympus-powered planes were based on ten UK airfields from the late 1950s and were assigned a readiness state called Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) during periods of international crisis. Positioned near base main runways, the Vulcans were required to be airborne in five minutes or less. They often carried air-launched nuclear weapons on their high-altitude missions. Gradually their role changed, and the companion Valiants and Victors experienced serious operational faults and set-backs. By the late 1960s Britain decided to switch its nuclear deterrent responsibility to the Royal Navy’s Polaris missile-equipped nuclear submarines. The V-bombers were phased out of service early in the 1980s and replaced in the air by the then-new Panavia Tornado multi-role force.

It took the gigantic resources of the Boeing Airplane Company to conceive, design, organize, sub-contract and manufacture the plane that was the mainstay of America’s strategic bombing force for most of the period since the end of World War II. Originally planned to carry four B-28 or B-61 thermonuclear gravity bombs in internal weapons bays, the B-52 Stratofortress first flew in April 1952, to replace the aging B-36 intercontinental bomber.

Beginning front-line service in 1955, the B-52’s capability was linked to the then-revolutionary Pratt and Whitney J57 jet engine, eight of which were needed to drive the huge plane. The J57 developed its great power (10,000 pounds thrust) through very high compression achieved by the use of two compressors in tandem, each turned by separate turbines. Later in the development of the bomber, it was re-engined with still more powerful, cleaner, and more economical turbofans.

Remembered chiefly for their bombing role in the Vietnam War, the big black-painted B-52s delivered 84,000-pound bomb loads on jungle guerrila targets and were said to be the American weapon most feared by the North Vietnamese. The B-52 is the longest-lived combat aircraft design ever produced.

In the 1980s, the U.S. Air Force wanted a bomber able to operate entirely on its own with virtual impunity against all conceivable air defenses, the airplane that would become the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber.

The bat-like wing configuration, the ability to operate on very short notice with no forward basing support, minimal detectability, enviable intercontinental range, and the wildly amazing price tag believed to exceed one billion dollars a copy, position the B-2 among the most outrageous man-made creations of all time. Originally, B-2 production was planned for 132 planes, but many factors, including the collapse of the Soviet Union, whose extensive radar network it was intended to evade, and the staggering unit cost of the advanced bomber, combined to reduce the final quantity to just twenty-one aircraft. The radically reduced order resulted in a lean, mean operational force more than capable in the view of its advocates, of delivering on its original broad promise.

The design criteria calling for ultra-low radar observability as well as exceptional aerodynamics, for a uniquely stealthy package led to one of history’s better-kept secrets. Throughout the 1980s, the black project was the subject of many rumors. The facts of its existence, capabilities and special design, however, remained secret until the Air Force decided to show it to the press and public at a November 1988 factory roll-out before the flight-test phase of development.

A Stuart Reid painting, Bombing of the Wadi Fara, 20 September 1918;

The Spirit can deliver a variety of conventional and nuclear weapons, including 500-pound to 2,200-pound general purpose bombs, sea mines, nuclear gravity bombs, and other ordnance. Fully loaded it weighs 336,500 pounds. With a range of approximately 6,000 miles, it can take off and land on any field capable of accommodating a medium-sized airliner. The B-2 operates with a fly-by-wire control system giving it fairly conventional handling and flying qualities. This radical airplane is made up largely of carbon-fibre-epoxy composite materials.

The B-2s are based at Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri and are operated there by the 509th Bomb Wing, descended from the WWII 509th Composite Group whose B-29s took the first atomic bombs to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The B-2 is meant to lead the attack in the first night of raids in any future conflict. It is dedicated to hit the best-defended, most vital and significant enemy sites. It can strike such targets from its U.S. base while operating independently and virtually on its own terms.

While not strictly a bomber, the incredibly versatile F/A-18 Hornet family of multi-role aircraft has for several years been the principal strike aircraft of the U.S. Navy. The Boeing McDonnell Douglas airplane first flew in 1978 and entered service in 1980.

Employee badge of a Pratt & Whitney aero engine plant worker in the Second World War years.

The Hornet is probably the most capable fighter-bomber in the history of the American Navy. In the Iraq and Bosnian conflicts the Hornet showed its worth in both the air-to-air and air-to-ground missions. It is a twin-engined, supersonic, all-weather, carrier capable combat jet with a top speed of 1,190 mph at 40,000 feet and can carry a wide variety of bombs and missiles. It is light-weight and relatively low-cost and is fairly small and easily accommodated in the limited space of an aircraft carrier. With a relatively small fuel capacity, its operation generally involves aerial refueling.

The Hornet was designed primarily as a naval plane to operate from carriers, but in the inventories of the Canadian, Spanish, and Australian air arms, it is operated from land bases. It is a highly automated aircraft whose computers significantly reduce the workload of the pilot, freeing him or her to concentrate on fighting the enemy and flying the mission. Its electronic offensive and defensive systems make it an extremely potent adversary. The Hornet has a gun, the M61 20mm cannon, an electric Gatling gun with a 540-round magazine, in addition to the ability to carry a combination of very capable weapons including the AIM-9M all-angle heat-seeking anti-aircraft missile, the AGM-88 anti-radar missile, and the 1,000-pound laser-guided bomb.

Pilots and maintenance personnel share respect for the F/A-18’s reliability and ease of maintenance, despite the complexity of its systems. In the Gulf War and over Bosnia, the Hornet force had an amazing availability rate of better than 90 percent, reaching a peak of 95 percent in the Gulf. No other naval attack aircraft has inspired such admiration and high regard from those who fly it.