HAVING ESTABLISHED two basic facts—that music is an integral part of African life from the cradle to the grave and that African music covers the widest possible range of expression, including spoken language and all manner of natural sounds—it may seem logical to conclude that everyone in black Africa must, by definition, be a musician. This is not necessarily the case in practice. It is true that most Africans do have a natural sense of rhythm which is one of the most characteristic features of African music. This instinct for rhythm not only produces a large number of talented percussionists, but also enables many Africans to master the techniques of more complicated melodic instruments. Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to assume that all Africans are necessarily musicians in the full sense of the word. Africans themselves are fully conscious of this fact.

In numerous African societies, the right to play certain instruments or to participate in traditional ceremonies is not open to all. Strict rules govern the choice of instruments to be used on specific occasions and the musicians who are permitted to play them. In Rwanda, for example, the privilege of playing the six royal drums, which were the royal emblems of the Mwami (the king of the Tutsi people), was reserved for one particular musician.1 In other communities, only young people of the most outstanding ability may entertain the hope of being called to fill the place vacated by the death of one of the “official” drummers. Such an event is marked by an important ceremony in which the late musician officially relegates his position to his successor. The musician’s corpse is seated before the drum that he used to play in his lifetime and the drum-stick is placed in his right hand. An elder of the tribe, or the orchestra leader, moves the dead man’s hand so that the stick touches the drum-head. Then, the new recruit takes the drum-stick and strikes the drum in exactly the same spot. He is then considered to be officially invested and may take his place in the community’s orchestra.

There are, however, other African societies in which music is not the privilege of a caste of specialists, but is a dynamic and driving force that animates the life of the entire community. This communal music may be quite elaborate in form, as is the case of the Pygmies who inhabit the equatorial forest. They live by hunting, gathering wild fruits, and bartering with villages on the edge of the forest; all their daily occupations are accompanied by music. Men and women, young and old alike, contribute their share to the collective enjoyment by singing, clapping, stamping, and other rhythmic actions. All Pygmies are musicians, otherwise they would be incapable of participating fully in the nomadic life of this race of hunters. Pygmy music is usually very sophisticated in rhythm and form, as well as in its ritual structure. Pygmies rarely sing in unison; the songs they perform to celebrate a successful hunting expedition are polyphonic in form with a fairly simple rhythmic pattern provided by handclapping and sticks struck one against another. Although their songs are constructed within a very strict framework, the performers are left with great freedom to improvise. In this type of community where everyone is a musician, the artist usually has no particular place in society to single him out from the rest.

A fine hunter and an excellent musician—a true Pygmy

The history of a town such as Tlmbuctoo owes just as much to the memory of these Tuareg musicians as It does to the written word .

In other societies musicians form a semiprofessional group. They earn their livelihood from their music for only part of the year and they rely on some other activity for the remainder of the time. There are Bambara farmers in Upper Volta who leave their fields every year during the dry season in order to travel hundreds of miles with their musical instruments. They go from village to village, enlivening local festivities with their playing and singing. They usually expect those who benefit from their visit to pay for the pleasure that they provide.

Music is by no means a profitable occupation for everyone in these communities. What is it, then, which attracts certain people toward music? Here is one answer which a semiprofessional harp-lute player from the Ivory Coast gave to Mr. Hugo Zemp:

“ …I was working at my loom one day, as usual, when suddenly I saw two dwarf-genii, who said to me, ‘Get up! Go home and hang yourself.’ None of the other weavers could see them. I left the loom and went home. I found a length of rope, attached it to a roof-beam and hanged myself. Some of the villagers had followed me home, so they cut the rope and then went to consult a soothsayer. He told them that in the past some of my relatives had been harp-lute players and unless I continued the tradition I was doomed to die. There had been no harp-lute player in our village since my father’s brother died. My relatives found the instrument, which had not been touched since my uncle’s death, and sacrificed a chicken. Then I set about learning to play the harp-lute. As soon as it became known that I had been ordered to play the harp-lute the people of all the neighbouring villages in the district began inviting me to play for them and I received many presents. Sometimes I was away travelling for weeks at a stretch. But during the farming season I always stayed at home to work on my plantation.”2

Because of a dream—or a vision—a man who had never touched a musical instrument before in his life became the best harp-lute player in his region. How did he intend to pass on his art? Would he teach his own children to play or did he look upon it as a personal gift? Here is his own reply: “I’m not dead yet, so I can’t teach anyone else to play the instrument. When I die the dwarf-genii will choose my successor. It could even be someone who isn’t a member of my family.”

We have not quoted this Baule musician’s actual words, which may appear rather naive, with the intention of amusing the reader, but rather, in order to illustrate the mystical, almost magical relationship that can exist between a man and his music. The fact that his vocation was prompted by some kind of supernatural revelation shows how closely magic and music are related in African society. Perhaps the similarity of the two words in English is not merely coincidental.

Magic and music—their secret is one and the same .

In this particular case, the element of magic went a stage further. The musician also relates that when the dwarf-genii ordered him to play the harp-lute, he was also given the secret of a cure for leprosy which he apparently used with great success. The use of the harp in healing leprosy is by no means exceptional; this instrument is invariably associated with the powers of healing that are granted by spirits. Nor is the experience of this musician from the Ivory Coast in any way out of the ordinary; all Baule harp players are known to communicate with the spirit world. This characteristic is echoed in many other African tribes. Most harp-lute players are also soothsayers or healers.

This story also demonstrates that people sometimes learn to play an instrument because they have been more or less forced to do so. Music is a communal undertaking and people tend to become musicians not so much from personal vocation as from a need to fulfill a social obligation. In this instance, the community needed a new harp-lute player. The choice of who he was to be was left to the dwarf-genii.

Semiprofessional musicians are not always, like the one we have mentioned above, isolated individuals. Very often they belong to one particular trade or caste, such as the Senufo orchestras that are composed of groups of blacksmiths, farmers, and other tribesmen.

Finally, we come to those African societies that have professional musicians. Such musicians live solely by their art and belong to particular families or castes. Their music is much more esoteric and is transmitted from one generation to another. These families or castes may be recognized by their characteristic surnames. Keita, Mamadi, Diubate or Dibate, Kuyate , and Sory are all names usually associated with griots , although it is not unusual now to come across people with these names who have received a European education and who have branched out into a profession quite different from that of their ancestors.

Griot is the term used throughout West Africa to designate a professional musician. What exactly is a griot? It may be easier to begin by saying what a griot is not. Contrary to popular belief, a griot is not merely an African witch doctor or sorcerer, although some griots do dabble in witchcraft. They usually specialize in the art of invoking supernatural beings of all kinds and sing their praises in order to ensure their pardon, protection or goodwill. However, the role of the griot in West African society extends far beyond the realm of magic. The fact that music is at the heart of all the griot’ s activities is yet further proof of the vital part he plays in African life.

Few European travelers who have actually met a griot have grasped the meaning of the role that he plays in society and they tend to make hasty and erroneous judgments. The French novelist, Pierre Loti, is no exception and concludes his description of griots in Roman d’un Spahi with these words: “Griots are the most philosophical and the laziest people in the world. They lead a nomadic life and never worry about tomorrow.” This rather uncharitable view does at least have the merit of placing the griot in his true perspective in time; he is more concerned with the past than with the future. By the past, we mean not only the history of his people—its kings and ancestors, and the genealogy of its great men—but also, the wisdom of its philosophers, its corporate ethics and generosity of spirit, its thought-provoking riddles, and the ancestral proverbs that serve as a reminder that everything on earth is destined to pass, just as time itself passes.

When the griot sings, even the sun at its zenith stops to listen .

The West African griot is a troubadour, the counterpart of the medieval European minstrel. Some griots are attached to the courts of noblemen, others are independent and go from house to house, or from village to village, peddling stories and adding new ones to their collection. The griot knows everything that is going on and he can recall events that are no longer within living memory. He is a living archive of his people’s traditions. But he is above all a musician, without whom no celebration or ritual would be complete. His repertoire is extremely wide and ranges from set pieces for special occasions such as weddings and christenings to songs in praise of individual customers that are composed to order. Griots who belong to the household of a nobleman are appointed to extol the glories and virtues of their master. Independent griots sing the praises of anyone who can afford to pay them and it would be the height of folly to haggle over the price. They are quick to flatter those who reward them well, but a discontented griot would not hesitate to slander and curse a less generous client and to brand him with the reputation of being a miser.

The virtuoso talents of the griot command universal admiration. This virtuosity is the culmination of long years of study and hard work under the tuition of a teacher who is often a father or uncle. The profession is by no means a male prerogative. There are many women griots whose talents as singers and musicians are equally remarkable.

Although the talents of these extraordinary musicians are much admired, it must be admitted that they rarely enjoy personal esteem. People fear them because they know too many secrets. They are often treated with contempt, and in fact, belong to one of the lowest castes in the social hierarchy along with the shoemakers, weavers, and blacksmiths. This attitude that prevails toward them is reflected in the legend that recounts how the ancestor of the griots came into being.

It tells of two brothers travelling through the forest. They were striding along bravely in the heat of the sun when the younger one was suddenly seized by violent pangs of hunger and said to his brother, “You’d better carry on and finish the journey alone. I can’t go a step further. I’m dying of hunger.” The elder brother pretended to agree and went on alone. But, as soon as he was hidden from sight behind a large clump of bushes, he stopped, drew out his knife, and cut a piece of flesh from his own thigh. He prepared the meat carefully and took it back to his brother who ate ravenously. He soon regained his strength and they set off again. After a little while, however, the younger one noticed that his brother was covered with bloodstains. He asked him what had happened, but he received no reply. Finally, when they had reached the next village, his elder brother confessed what he had done to help him, whereupon the younger brother made the following vow: “In order to save me from death, you did not hesitate to give me the flesh of your own thigh. Henceforth, I shall be called Dieli , your servant, and all my descendants will serve your descendants.” This is how Dieli , the ancestor of the griots , is said to have originated and the name is still used today by the Fali of Guinea and the Bambara of Mali to designate griots .

Contrary to popular belief, a griot isnot a kind of African witchdoctor, but primarily an extraordinarily gifted musician .

This legend explains allegorically why griots have come to occupy such a lowly rank in society. There is no escape from the rank even after death. In some parts of West Africa, griots were not allowed the right to a proper burial. People believed that if a griot’s body was buried in the normal manner, it would render the earth perpetually barren. When a griot died his body was placed inside the hollow trunk of a gigantic baobab tree. A tree-cemetery of this kind was discovered some years ago in Dakar (Senegal). The huge trunk contained a vast quantity of bones.3

This mixture of admiration and scorn, which is the lot of a class of men whose very existence depends upon what they find to say about other people, reminds us of the words of Aesop, the ancient Greek fabulist. When asked why he considered the tongue to be both the best and worst of things, he replied, “Because it can not only be used to praise the gods but is also an organ of blasphemy.”

“Whether they are looked upon as the upholders of tradition or the inventors of new melodies, poems and rhythms, their existence,” says André Jolivet, “has one supreme merit: it is a striking example of the importance of music and the musician. It is not altogether displeasing that this truth should be brought home to us by people who may still be young politically speaking, but whose roots are firmly established in the primordial forces of nature, from which they draw the essence of their material and spiritual life.”4

The disrespect and scorn shown to the griot by his own community has the rather dubious advantage of illustrating some of the general problems indigenous to the African artist in society. Recent conferences on African art and culture have reproached Africans, sometimes in rather harsh terms, for not always recognizing the true place of the artist in society; that is to say, in a new African society that has evolved considerably from traditional African communities. Governments and cultural centres are being urged to study the problem of the African artist in hopes of according him his rightful place—a place of honour, needless to say. However, it must never be forgotten that despite this evolution in African society, we are still dealing with peoples of tradition and two important facts usually seem to be overlooked. In the first place, people tend to forget that in African communities where art is a living and popular birthright, the artist, far from being scorned, usually occupies an enviable position in society. For instance, the medicine man or healer encourages the entire community to participate in the dances that he employs as part of his therapy and no one would ever dream of relegating him to an inferior position. The role of those artists who are essential to initiation ceremonies— ceremonies that are a combination of philosophy, mythology, technique, and art—leaves no doubt as to their importance in society. The other fact that should not be forgotten is that the art of the griot is essentially contemplative (hence static), individualistic, and preeminently self-interested. It is not orientated toward the future, but firmly entrenched in the past. It is not a collective art form; this is a distinct disadvantage in societies where art is regarded as a communal undertaking. When the griot speaks or sings, he expects immediate attention and he is ready with an insult if such attention is not forthcoming. Most griots are self-seeking and would not deign to perform unless they were sure of their reward, either in money or in kind. If we take all these facts into account it is clear that the problem of the griot is not, as it may at first seem, common to all African artists. Rather, the griot is a special case that must be treated separately.

The drum Is not the only Instrument of the griots, nor for that matter Is It the sum total of African music .

Leaving these arguments aside, it cannot be denied that griots are extraordinary musicians with outstanding talent who play an extremely important role in their respective societies. Their knowledge of the customs of the people and courtly life in all countries where they exercise their art gives them definite advantages; for the whole life of the people, its monarch, and ministers, is preserved intact in the infallible memory of the griots .

The equivalent of the griot in equatorial Africa is the player of the mvet or harp-zither. He may not be as well-known outside of Africa as the griot , but he is no less interesting or less famous within his own society. There, he combines the multiple functions of musician, dancer, story-teller, and storehouse of oral tradition. He is, in some ways, more fortunate than the griot for the admiration that he enjoys is not tinged with scorn. This is probably due to the fact that the mvet player’s repertoire does not normally include the improvised songs that are composed to order in praise of the rich. The repertoire of the Fang mvet players of south Cameroon and Gabon, for instance, consists mainly of stories, epic legends, heroic deeds, and marvels—a favourite topic being the struggle for power between the mortals and immortals. “On earth, Ovang-Obam-O-Ndong, aided by Ondo Zogo (whose weapon is a withered human arm) is recruiting an army of volunteers in an attempt to capture immortality from the kingdom of Engong, where it is closely guarded by the chieftain, Akoma Mba. Many trials await him when he enters this kingdom, but he will overcome them bravely with the help of his army. But, at the end of the poem (which lasts a whole night) he will once again fail in his undertaking.”5

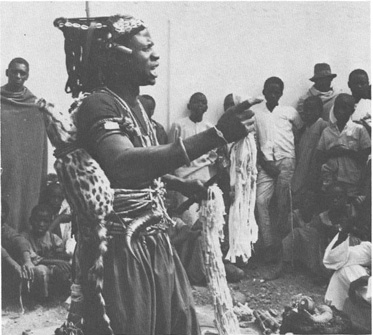

Music as a sales technique: This vendor of talismans and amulets attracts his clients’ attention by singing the praises of his wares .

The mvet is a kind of harp-zither. The strings are stretched along a raffia-palm stalk and raised over a bridge situated halfway along the stalk. The sound is amplified by a sound-box consisting of one or more gourds. The musician himself is usually bare to the waist and beside a raffia skirt, he is adorned with necklaces, bracelets, and a large quantity of feathers. He is an amusing sight for foreign eyes, perhaps, but as soon as he makes his appearance in the village square he is surrounded by an excited crowd. He has only to sketch a dance movement and all the jingling bells and beads he wears round his ankles and wrists invite the onlookers to gather around and dance with him. He has only to hum the first few notes of the verse of a song and, as though by magic, the crowd seems to find the corresponding chorus. After these preliminaries, the eagerly awaited story begins in earnest and the audience settles down for the night; the end of the tale will come only with the dawn.

Then they came to the Tribe-of-Visions

Commanded by Ondo-Minko-M-Obiang

r …r …r …r … (sound of a marching army)

And then – just imagine!

Ondo-Minko-M-Obiang the crocodile-man

Began shouting at the top of his voice:

‘The idiots! Where on earth are they going?

Look at the way they march!

Hey! Stop!’

(Then, leaping forward): Kilit! Vivm! Hi! (onomatopoeia)

He barred the road to the army

And challenged Ondo-Zogo:

‘What’s happening? Where are you going?’

And Ondo-Zogo of the Tribe-of-the-Strong-Hands

Replied:

‘We are going to the land of Engong-Nzok

To see Mobege, the brother of Mba, from the village

Of Fatu-Fe-Meneno.’

(Ondo-Minko-M-Obiang): ‘Who is your chief?’

(Ondo-Zogo): ‘Ovang-Obam-O-Ndong

Of the Tribe-of-the-Fog.’

And do you know what happened next?

This crocodile-man Ondo-Minko-M-Obiang

Ordered:

‘You shall not pass!’

And striking his chest with a resounding blow

He drew from his mouth a great crocodile stone,

Which he threw with all his might

In Ondo-Zogo’s face, where it broke.

Ondo-Zogo of the Tribe-of-the-Strong-Hands

Staggered like someone about to fall

But, listen carefully, in spite of that he straightened up,

Brandished the withered arm he carried as a weapon …

And struck Ondo-Minko-M-Obiang

A violent blow on the mouth: Tos! (onomatopoeia)

So hard that all his teeth fell out: Folot – Folot (onomatopoeia)

And then – would you believe it? – Ondo-Minko-M-Obiang just stood

there

With his teeth in his hand

Watching the column pass by. Yi, yi, yi, yi (laughter).

The laughter that interrupts the story at this point corresponds to the falling of the curtain at the end of an act. The audience, which has been listening intently up to this point, relaxes for a few moments while the mvet player asks, “What can your ears hear?” and the crowd shouts back, “They can hear the mvet .” So the mvet strikes up, sometimes in solo and sometime to accompany a song in which the entire audience participates. After this interval comes the next episode in the long story of Ovang-Obam-O-Ndong among the immortals.

This repertoire, a mixture of music and epic poetry, is extremely ancient and has remained constant in form and content for many generations. This would seem to justify the words of Mr. André Schaeffner of the Musée de l’Homme in Paris who writes, “In the universal history of music the African Negro, like the Arab, is not really a creative musician but a natural musician, in the fundamental sense of the word.”6 However, we must point out that a griot who recites the family tree of a king or a harp-zither player who retraces the legendary steps of the heroes who set out to conquer immortality represents only one aspect of the African musician. And even within this unchanging framework of content and form, there is always plenty of scope for improvisation and ornamentation so that individual musicians can reveal their own particular talents and aptitudes. Thus, no two performances of any one piece will be exactly alike. Admittedly, Mr. Schaeffner goes on to add that the African musician is “amazingly gifted, sensitive to the slightest influences and capable of assimilating them without losing his own identity.” What greater proof could there be that the African musician has a personality of his own, which is without any shadow of doubt an attribute of any creative artist? Mr. Schaeffner also points out that the black man is both “sensitive and distorting”; but in art, distortion can result in the creation of new forms. In fact, this so-called “natural” musician makes a true contribution to the evolution of his art precisely because he enjoys distorting what he borrows from nature or from other people. In other words, his “naturalism” is by no means a foregone conclusion and it should certainly not be equated with “primitiveness” merely because many of the instruments used in black Africa are archaic. The African is fully conscious of his art and capable of approaching it imaginatively. He is certainly “open” to influences and does tend to “simplify”, but it is not true to say that “although he proves to be open, he tends to withdraw into a dark, naïve universe which is his and his alone.” This statement is inaccurate in regard to several points. This “universe” is not exclusive to the musician, for music is a collective art and the musician’s basic role is to guide and coordinate. Secondly, it is not at all a “naïve universe”; the musician knows the precise significance of his music and its role in society. His apparent naivety is deceptive and can only mislead those whose acquaintance with him does not penetrate deeply enough. In this particular context of mysticism and faith, the term “naïvety” makes absolutely no sense. Faith is the universal armour which protects all avant-garde creative artists from the slings and arrows of criticism.

The mvet harp-zither of the Fang story-teller Is the African counterpart of the Greek bard’s lyre .

“Then they came to the Tribe-of-Visions Commanded by Ondo-Minko-M-Obiang …”

Finally, the universe of the African musician is anything but “dark”. It glows with the radiance of life itself. The funeral music of the Dogon of Mali or the Fali of Cameroon demonstrates their refusal to accept death. Rather, they substitute the notion of metamorphosis into a bird or snake for that of death. They have a wealth of satirical songs that mock the idea of death “which would like us to believe that when it arrives we stop living.” It is hardly likely that anyone with such a deep faith in life—especially an artist—would withdraw into a “dark” universe.

No, the black musician is not naïve, but what sometimes puzzles the non-African is the simplicity with which a black musician approaches his art. He does not reserve his extraordinary talents for his immediate circle, but shares them with anyone who is willing to listen. He rarely considers himself superior to others. Even the greatest musicians whose fame has spread throughout their country, thanks to the radio, rarely behave like celebrities. Many Europeans are amazed to see first-rate African musicians agreeing to record for the radio without any payment. In other climes, a good musician automatically assumes he will be paid the fees he deserves. If we leave aside the griots , it is rare to come across anyone in traditional African society who thinks of his music as his sole means of livelihood. More than one recording company has exploited the generosity of the African musician. In the 1950s, many 78 r.p.m. records of traditional and more modern African music were made under such circumstances with the artists sometimes being rewarded with nothing more than a bottle of locally brewed beer.

This, then, is the Africian musician—an artist who dedicates himself to the service of the community at large. Times change, but in Africa today this is true as never before. The African continent is developing rapidly and the attractions of urban life have set in motion an ever-increasing rural exodus. Each year, hundreds of young people leave their traditional environment where music has such a special meaning and are engulfed in towns where only a handful of individuals attempt to keep alive some of the customs of village life. The process of development cannot be halted and it will not spare traditional music or its exponents. Traditional musicians must, therefore, prepare to defend themselves against the inroads of modern times and try to ensure that their music will evolve in a way that will safeguard its authenticity.

One of greatest dangers facing the traditional African musician today is an inferiority complex engendered by the knowledge that most townspeople prefer the imported music dispensed, rather over-generously perhaps, by the radio and on records. In the past twenty years, these two mass media have opened the floodgates to a literal invasion of imported musical forms and they have already succeeded in making some Africans virtually forget the existence of the music of their traditional societies. In such circumstances the musician feels obliged either to abandon his so-called primitive art altogether or to attempt to bring it up-to-date. We once recorded a Lobi xylophone player who exemplifies the problem confronting the musician. This musician from the north of Ghana had arrived in Accra only two days before we met him and he soon encountered some people from his own tribe who invited him to listen to some European and American pop records. They were so full of enthusiasm for these talented foreign musicians that they managed to persuade him to abandon the “primitive” music he performed so brilliantly on his xylophone. Within two days, Kakarba had produced four new pieces, using borrowed jazz rhythms and a delicate ballad style which ill-suited his xylophone, particularly as the scale of the instrument bore precious little resemblance to those found in pop music. However, we agreed to record him, because we believed in all sincerity that these efforts to modernize his music deserved encouragement even though they were founded on an inexplicable feeling of guilt. After he had performed his new compositions, we begged him to play some of the authentic tunes of his village. He was rather reluctant at first, believing that after the masterly performance he had just given, his traditional music would come as an anticlimax. However, after an exhausting session, he finally had the chance to listen to everything he had recorded and he was the first to admit that the typically African themes were infinitely more beautiful and more expertly played than his attempts at modernization. Despite all the attractions of imported music and a conviction that his art must evolve, here was a musician intelligent enough to acknowledge the beauty of his traditional art.

The story of this particular musician illustrates another vital factor; in their own communities, musicians have no way of knowing what their own music sounds like and the tape recorder can be of enormous benefit to them. Our friend from northern Ghana had certainly never before in his life heard his own music as it sounded to an audience. To sit and to listen to it properly through a loudspeaker, as though he were listening to someone else, was nothing short of a revelation for him. The story has a happy ending because we managed to convince Kakarba of the validity of his village music which he decided not to abandon after all. One hopes that material difficulties will never force him to trade his traditional culture for the comforts of modern life.

Such difficulties are, indeed, another of the dangers which threaten traditional art as a whole, and music in particular; like most of his fellow-citizens, the African musician is feeling the effects of the revolution that is sweeping the entire continent and is raising expectations of higher standards of living which only a lucrative form of employment can satisfy. Music, as it is conceived in traditional society, is not a function which enables its exponents to meet the demands of modern life. Moreover, as we have already pointed out, the competition is enormous and under these conditions music as a profession offers very little opportunity. In some societies, music is not conceived as a profession at all, a fact which is even more limiting. As things exist today, then, traditional music is threatened with eventual extinction and will gradually disappear unless immediate steps are taken to assure the future of its most essential ingredient—the musician himself.

A master of ceremonies sometimes leads the dance In the manner of an orchestra conductor .

The West is at last becoming aware of the cultural value of African music and a number of people who live outside of Africa are making prodigious efforts to preserve this particular art form. Thanks to the activities of various recording companies, an increasing number of well-documented records are now available (many of which will be mentioned in more detail later in this book). Record libraries that store all types of folk music on tape are springing up in Europe and America. An excellent system of cataloguing makes it comparatively easy to locate any given item, from a Fulani flute solo to a Malinke lullaby. We should single out the efforts undertaken in France by OCORA Records who make and distribute excellent records of the traditional music of the peoples of black Africa and who have a record library that is a model of its kind. We shall come back to these impressive achievements at a later time but presently we feel compelled to state that in our opinion preservation is not enough. The recording, preservation, and diffusion of traditional African music must be accompanied by a parallel effort to preserve and emancipate the men who create this music—to provide them with a favourable climate in which to progress so that they can gradually take their rightful palce in universal culture. Unless these things are accomplished, and accomplished quickly, African music will be unable to offer the world more than a fraction of its fresh and invigorating lifeblood.

d invigorating life-blood.

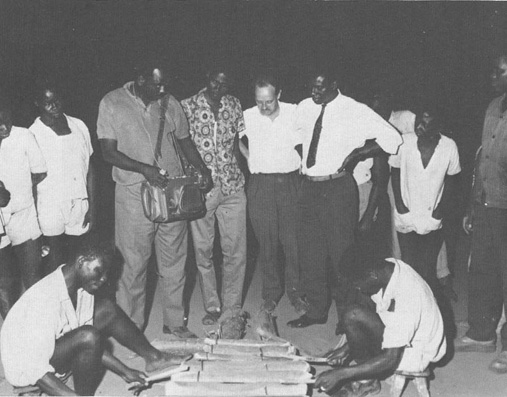

The tape recorder can enable a musician to discover his own music when he hears it for the first time .

… to keep their ancestral musical treasures intact and hand them down in the traditional manner to the younger generations .

This does not imply that the traditional African musician should be sheltered from the infiltration of foreign influences. Such infiltration may, of course, represent a certain danger, but it can also be a source of artistic enrichment. We believe that a combination of different artistic and cultural values can, in some cases, have a beneficial effect, but only when the native artist is fully conscious of their respective merits. To avoid succumbing prematurely to foreign influences, it is vitally important for the artist to begin by acquiring a thorough knowledge of them. The African musician must begin by familiarizing himself with the music of his own social environment and that of other African societies. Only then should he embark on a detailed study of non-African music—European music in particular. After this period of apprenticeship, the musician will, if he so desires, be equipped to venture into the extremely delicate field that is known as the “marriage of cultures.”

This is often a matter of intuition rather than a logical and scientific act of reasoning. If the assimilation has gone deep enough, a composer can no longer consciously weigh the proportion of European and African music he pours into his work in order to obtain satisfactory results; the assimilation will happen automatically.

However, we must be realistic and face the situation constructively. Africa today has innumerable problems to solve and music, despite its importance, is only one among many others. It may be years before the majority of traditional African musicians have the opportunity to reach that perfect assimilation of differing musical values that is so essential to the evolution of the music of the African continent. For the present, therefore, it may be wiser to concentrate on encouraging villagers to keep their ancestral musical treasures intact and to hand them down in the traditional manner to the younger generations. In this way, we hope that the time will come when a future generation of Africans will have both the knowledge and the opportunity to operate a synthesis of cultures.

Encouraging the African musician Is the only way to ensure the survival of traditional music and enable It to make Its full contribution to universal culture .