BLACK AFRICA POSSESSES an infinite variety of musical instruments that is unrivaled except perhaps in Asia, Some of these instruments are made with placed in the sound-box to add their dancing rhythms to the music; drums sometimes have snares. All manner of contrivances are used to produce a variety of sounds—muted, nasal, or strident—that are intended to bring the music as close as possible to the actual sounds of nature. At the same time these devices allow more versatile instruments to be made—instruments that are sometimes capable of playing a melodic line with simultaneous percussion accompaniment.

Such idiosyncrasies and variations notwithstanding, most of the musical instruments found in Africa fall into one or another of the classical categories used in the West. Like Western instruments, they can be divided into stringed, wind, and percussion instruments and can quite easily be placed in one of the four main classifications: chordophones (stringed instruments), idiophones (instruments that produce sounds from substances not stretched or altered in any way, as opposed to stringed instruments or drums); aerophones (wind instruments); and membranophones (instruments with one or more stretched skins).

However, to do full justice to the extraordinarily wide range of instruments in black Africa it is advisable to use a slightly more detailed system of classification; that is: stringed instruments; wind and air instruments; keyboard instruments; drums, with or without skins; rhythmic instruments with vibrating bodies (no strings, skins or keys); corporal instruments; other miscellaneous instruments. We shall examine several of these categories in some detail, referring wherever possible to records that illustrate the corresponding instruments.

There are three types of stringed instruments: bowed (fiddles), plucked (harps, lutes, zithers, harp-lutes, harp-zithers) and beaten (musical bows, earth-bows).

The best-known of the bowed-stringed instruments is the one-stringed fiddle that is used by West African musicians, particularly in Muslim regions. It is known by various names in the north of Cameroon and Nigeria, in Chad, and throughout almost the entire zone that extends from Lake Chad to Senegal. The Wolofoî Senegal call it the Riti , the Tukulor Nyanyur and the Songhai and Djerma of Niger refer to it as either the Godie or Godje; elsewhere in black Africa, it is simply the Hausa violin .

The sound-box is made of wood or a hemispherical calabash with a nailed skin, usually lizard skin. A single, horse-hair string is attached to a short neck and stretched over a bridge. A hole is made in the sound-box or in the skin to allow the sound to “escape,” as the musicians put it. The bow is a curved stick with a horsehair string that is fixed to both ends. Most one-stringed fiddle players are such gifted musicians that they almost give the impression that the instrument has more than just one string. The timbre recalls that of the violin or viola, or even the cello, depending on the region and the man who made it. The volume of the sound is in proportion to the size of the instrument and the bow is naturally scaled to size.

Riti—the one-stringed fiddle of the Wolof musicians of Senegal

One-stringed fiddles may be used as solo instruments but are chiefly employed to accompany singers. They provide the favourite accompaniment of griots in Niger, northern Nigeria, and the Timbuctoo area of Mali.1

In Niger, there is a type of one-stringed fiddle call Inzad that is usually reserved for female musicians.2 It has a wooden neck that is inserted into a half-calabash, covered with goatskin. A small circular opening in the skin, close to the bridge, is the feature that distinguishes the Inzad from other instruments of the same type, in particular from the two Senegalese fiddles mentioned above—the Wolof Riti and the Tukulor Nyanyur . The sound-box of the riti is also hemispherical, but is made from the wood of the silk-cotton tree and is covered with lizard skin. The skin is left intact and instead one or two holes are bored in the underside of the sound-box.3

A one-stringed fiddle played by a woman from Mall

But although the one-stringed fiddle is found in many parts of West Africa, Niger is perhaps the country where it is employed to the best advantage. The musicians of Niger can really make the instrument “speak” their respective languages with such a wide range of expression and volume that at times they seem to be making a speech to a vast audience and sometimes to be whispering confidences. They frequently make remarkable use of magic harmonic notes, similar to those of the violin.

The resemblance between fiddle music and singing reaches its peak among the Tamashek nomads of Niger. Some of their love songs create the distinct impression that voice and instrument are singing absolutely interchangeable phrases in content as well as in form.4

The one-stringed fiddle can also have the purely functional role of creating and maintaining a suitable atmosphere for the performance of certain rites. The magical incantations used in Mauri and Djerma music (Niger) to invoke the genii, Babai or Zatau, are excellent examples of this usage.5

It is interesting to note that Nago and Yoruba musicians (Nigeria or Dahomey) use the Godie one-stringed fiddle in modern African dance bands.6 The fiddle assumes an almost human role in these bands and reproduces speech patterns and inflections note for note. This “conversation” between the fiddle and the rest of the orchestra is somewhat reminiscent of the Western concerto.

The most spectacular form of “talking” fiddle is found in Ethiopia where it is the favourite instrument of professional musicians who wander from village to village with their “musical newspaper.” A strolling musician singing the news to the accompaniment of a Masengo fiddle has been recorded.7

Instruments of the fiddle variety are rare in the Congo, but we shall conclude this section with the recording of a Ba-Lari song that is accompanied by a Nsambi fiddle with three strings.8

Instruments with plucked or beaten strings have a much wider geographical distribution than the previous group of bowed-stringed instruments, and are more varied in kind, for example, one-stringed lutes—the Molo (Senegal) and the Kuntigi (Niger); two-stringed and five-stringed lutes; the harp-lute—Kora or Seron (Guinea); the Bolon harp (Dahomey); the bow-lute of the Bateke (Congo); the mvet harp-zither of southern Cameroon, and others.

The listener cannot fail to be enraptured by the skills of the African musicians who play such instruments and to see them in action is an added pleasure. The playing of a Senegalese griot prompted the French musician, Tolia Nikiprowetzky, to exclaim, “It is marvellous to see how Amadu Coly Sall, using a simple instrument like a one-stringed lute, manages to capture and hold the listener’s attention.” And he continues, “His feats of instrumental virtuosity are enhanced by the charms of constant modal ambiguity.”9

Konde—two-stringed lute (Upper Volta )

There are several kinds of lute, varying from region to region in name, shape, and number of strings. In Senegal, the lute goes under the general title of Khalam and usually has five strings. The Khalam is the favourite instrument of certain griots . There are four distinct types: the Diassare , the Bappe , the Ndere , and the Molo . The latter is a one-stringed lute that can be used in several ways, either as a solo instrument, or to accompany another Khalam or a singer,10 or even a story-teller. The poet, Leopold Sédar Senghor, advocates the use of the Khalam to accompany some of his poems.

The Bussance of Upper Volta play a two-stringed lute known as the Konde . It consists of a half-calabash that is covered with a skin; the neck has metal bells attached to the end so that when the strings are plucked, the bells jingle. The Konde belongs to that category of African instruments whose main purpose is to “speak” rather than to sing.11

In Niger the most interesting lutes are the Kuntigi 12—a one-stringed lute used by the Songhai and the Djerma , and a three-stringed lute—the Teharden , played mainly by Tamashek musicians. A similar three-stringed lute is used by Mauri musicians.13

The Kuntigi is a small lute with a hemispherical calabash sound-box that is covered with skin. The neck is a slender stick whose free end is fitted with a metal disc surrounded by small rings that clash together at the slightest movement of the instrument, thus providing a rhythmic jingling when the musician plays. The tone of the instrument is shrill yet veiled, like most African lutes that have a sound-box covered with skin. This lightly veiled tone can also be heard on the recording of the Senegalese Khalam Molo , although the latter has a larger sound-box which gives a deeper, more powerful resonance.

Finally, in northern Nigeria, mainly in the region of Zaria, there is a two-stringed lute called the Komo . It is approximately 2 feet, 3 inches long. The strings are made of twisted antelope skin and are plucked with a hippopotamushide plectrum. The upper end of the neck is fitted with a rectangular piece of metal with rounded angles. A number of small vibrating rings are fixed around the perimeter.14

The zither is another instrument with plucked strings but, unlike the lute, it has no neck. Zithers of varying shapes and tones are found in certain parts of Africa and also in Madagascar. Most of the recordings available were made in Rwanda, Dahomey, and, above all, in Madagascar.

The Inanga zither from Rwanda consists of an oval-shaped piece of wood that is hollowed out so that it resembles an elongated bowl. The strings are stretched lengthwise along this piece of wood and are held in place by a series of notches at either end. In fact, there is just one long continuous string that is wound from one side to the other alternately in order to form a set of parallel strings whose tension can be regulated by means of the sharp saw-tooth notches.15

The Mahi of Dahomey play a raft-zither known as the Toba . The strings are stretched lengthwise along a rectangular portable raft that is made from woven reeds. The strings are rather unusual because they are not separate additions, but are actually cut and lifted from the reed bark. The Toba has no sound-box and consequently, it has a rather feeble tone. Some musicians amplify the sound of the instrument by holding it over an empty receptacle, such as a bucket. In any event, the instrument is held in both hands and the strings are plucked with the thumbs.16

Malagasy zithers are of particular interest. The construction and evolution of the instruments themselves and the music they produce, or are capable of producing, merit special attention. Of the two Malagasy zithers that have been recorded, the Valiha is perhaps more interesting than the Lokanga Voatavo .

Inanga zither (Burundi )

The Lokanga Voatavo zither is composed of a number of strings stretched along a stick, one end of which is inserted into an open-bottomed calabash that acts as a sound-box. The stick itself is decorated with intricate carvings and the free end is shaped like a fishtail. In the recording of the Lokanga Voatavo , we have chosen as our example two zithers that can be heard accompanying the voices of the musicians.17

The Valiha is by far the most widespread instrument found on the island of Madagascar; it might even be called the national instrument. It usually consists of a bamboo tube with strings stretched longitudinally around the circumference. The length of the tube varies between 1 foot, 6 inches and 4 feet, 6 inches. Bamboo strings are sometimes used, but nowadays most Malagasy musicians prefer metal strings, which increase the limited volume of the instrument whose sound-box is of very small dimension. The bamboo-stringed zither is idiochordic, that is, the strings are not external additions, but rather, thin strips raised from the body of the instrument

A Malagasy playing the Valiha or tubular zither

The harp family is represented in certain areas of Central and West Africa. African harps are used chiefly to accompany singers. The number of strings varies from one locality to another and even from one individual maker to another. The most widely used model in Central Africa is the bow-harp which may have one single string (among the Fang of Gabon) or ten or so strings (among the Isongo or the Mbaka of the Congo).

The one-stringed bow-harp is frequently used in quite a remarkable fashion; as well as playing a melodic accompaniment, it simultaneously acts as a percussion instrument. The musician achieves this effect by alternately plucking the string and tapping out the rhythm on the sound-box.20

The Senufo use one-stringed harps made from large, trisected calabashes that are covered with skins. They have a long curved neck that is finished off with a metal disc, surrounded with metal rings that produce rhythmic rattling sounds.21

There are several varieties of bow-harp in Chad. The Massa of Western Mayo-Kebbi have a four-stringed version, the Dilla , while in Muslim communities, there are musicians who use a five-stringed bow-harp, the Kinde , which is placed laterally with the strings parallel to the ground.22

The Ngombi is another bow-harp that is composed of some ten strings; it is found mainly in the Central African Republic. It provides a much fuller accompaniment for songs and several excellent recordings exist.23

A Wombi or eight-stringed harp has been recorded among the Pongwe of Gabon24 to accompany a song used in the healing of a sick person. A woman who is a professional healer practises the abandji method by which she can transform herself into a supernatural being in order to see into the next world. Thus she is able to find out how to select the barks and leaves that enter into the composition of the baths that are to be administered to the patient. The Wombi harp is the medium which leads the woman’s spirit into the land of the sirens. The head of this harp is often carved in the image of Ditsuna, the Goddess of Day.

On similar lines is a sacred harp that was also recorded in Gabon.25 Members of the Bwiti , a secret society for the men of the Bahumbu tribe in Gabon, gather in the forest to sing the praises of the sacred harp and to address their prayers to it. The sequence begins with a prelude that is played with outstanding virtuosity on the harp. Then, the priest of the sect sings the words of praise; these words are repeated after him by the congregation:

“Oh harp, hewn one night from the wood of the budzinga and the bukuka trees by the bunyenga spirit and the Sky God, grant that we in this country may receive the strength and wisdom of the crocodile, through the intermediary of the bukuka …”

This example of the deification of the harp illustrates the remarks made on page 20 concerning the relationship between musical instruments, genii, and men. Through the agent of music, the genii confer supernatural powers upon the instrument. In this case, however, the harp has an even more important role; it is not merely the vehicle through which the power of the genii is transmitted to man, but is the actual embodiment of the genii and their power.

A musician from Northern Nigeria playing an eight-stringed harp

Description of a journey sung by Massa musicians (Chad) to the accompaniment of three Dilla four-stringed harps

We must also mention the forked harp, an example of which has been recorded among the Baule of the Ivory Coast.26 It consists of a forked branch across which five strings are stretched. A half-calabash situated at the join of the fork acts as a resonator. In this recording, the harp is used to accompany a drinking song whose infectious gaiety is apparent, even though the lyrics may be incomprehensible. This is a typical example of Baule polyphonic technique that consists of a melodic line that is sung simultaneously on two parallel thirds.

The Bolon is a large, three-stringed harp which used to be featured in military parades.27

However, these lutes, zithers, and harps that have their counterparts in Western music are by no means the most outstanding members of the pluckedstringed instrument family in black Africa. The composite instruments that combine the different features of these instruments are much more remarkable, such as the Kora , a harp-lute from West Africa, and the Mvet , a harp-zither that is found mainly in Central Africa.

Loma harp (Liberia )

The Kora28 is one of the most beautiful musical instruments in the whole of black Africa, both visually and aurally. It consists basically of a sound-box, a neck, a large bridge, and 21 strings. The sound-box is a large half-calabash over which a skin is stretched. A hole is cut in the convex part and its contour is carefully decorated. This hole that “allows the sounds to escape naturally” corresponds to the sound hole of the Western lute. Sometimes the entire circumference of the sound-box is decorated, but this is by no means a general rule. A long, cylindrical, wooden neck is inserted into the sound-box. The strings are attached to the end that extends some 1½ inches beyond the sound-box and are fixed at 21 different points to the other end (the neck proper) by means of leather rings that are spaced out along its length. These rings slide along the neck in order that the strings can be held at the required tension for the tuning of the instrument. The bridge, approximately 8 inches high and 1 to 2 inches wide, has ten notches on one side and eleven on the other. The bridge and neck form two sides of a triangle that is completed by the strings that are stretched between them. It is basically this string-feature that places the Kora in the harp category. However, because it has a neck it must also be considered a lute. It is therefore more correct to refer to it as a harp-lute. Because the bridge divides the strings into two separate rows, ten on one side and eleven on the other, the Kora is actually a double harp. As a finishing touch, the musicians usually fix a round metal disc on top of the bridge. The small rings that are attached to the perimeter of the disc are intended to rattle at the slightest movement. This creation of impure sounds is a feature that we have already mentioned elsewhere.

In ascending order, the notes of the Kora are: F—C—D—E— G—Bb—D—F—A—C—E (left hand) and F—A—C—E—G—Bb— D—F—G—A (right hand). However, in spite of the theoretical accuracy of these notes, each one may in practice be a comma higher or lower; this fact often leads Europeans to imagine that the instrument is out of tune. It should be noted that the above mentioned scale is the tuning of the Senegalese Kora , as adopted by the School of Arts in Dakar. In Mali and in Guinea where the instrument originated, the tuning is not necessarily the same and is even further removed from the scale of Bach.

In Guinea, there is also a 19-stringed Kora called the Seron . In all other respects, the instruments are identical and are played in a similar manner. Some excellent recordings of the Seron are available. We would like to single out the solos played by an authentic griot from the Kankan region of Guinea, a griot who ably demonstrates the resources of the instrument.29 This is purely instrumental music of a very high quality and although the musician knows absolutely nothing about American jazz, it is hard to listen to his playing without being reminded of Negro-American music, notably the Modern Jazz Quartet. The music of Mamadi Dyubate—a name more typical of the griot caste would be hard to find—is not unique in this repect, but we would still hesitate to cite this as proof of the African origins of jazz.

How to hold the five-stringed harp from the Central African Republic

The Kora itself is found in a geographical area which includes Guinea, Gambia, Senegal, and southern Mali. Numerous recordings exist of the Kora as a solo instrument, as an accompaniment to a singer, and as part of an orchestra. As a solo instrument, it may be heard on a record issued in connection with the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar (April 1966)30. As an example of a song with Kora accompaniment, we would cite a song in praise of Sundiata, the legendary Emperor of Manding.31 Like all the other pieces on this particular record, it was made in Paris during a visit of Keita Fodeba’s African Ballet Company and it is performed by a griot called Dieli Magan. Some purists have shown a certain scepticism about the authenticity of this music, which could in some ways be described as “export art” that is presented by a company that was specifically formed to appear on the music hall stage. However, it must be remembered that the aim of Keita Fodeba and his African Ballets was to promote a mixture of traditional musical and choreography and the modern dance music and dance forms that were currently evolving in contemporary Africa. To omit either of these aspects would not give a balanced picture of Africa. For this very reason, both records made by this company32 and the variety that they offer are of genuine interest and importance. The over-westernized music of some of the pieces, such as the “Trio Melody Tam-Tam,” may not necessarily appeal to all tastes, but the authenticity of the traditional music that is played by the genuine griots in the company cannot be question.

Solos and accompaniment to singers are not the only uses of the Kora; it can also be found in orchestras or in instrumental duets—with a balaphon for instance.33 In orchestral ensembles, two Koras may be heard with drums, accompanying a singer and a mixed choir.34 The Kora’s effectiveness as an accompaniment to the human voice is perhaps best illustrated in the songs of the late Guinean singer, Konde Kuyate, one of the greatest women griots of black Africa. This accompanying role of the Kora is shown to particular advantage in the “Song of Siraba”35 and in the sublime “La illah ila Allah.” This song of praise, “There is no god but God,” is one of the most beautiful examples of traditional African music and Konde Kuyate’s interpretation enhances its beauty and depth of meaning.36 A discreet yet effective accompaniment, consisting of a single phrase that the Kora repeats incessantly throughout the piece, sets off the pure, persuasive development of the vocal theme, “There is no god but God.” If the melody were transcribed it would be in 6/8 time which gives the whole piece a calm composure that seduces the ear from the first few notes. The Kora heard in this recording has some metal strings, and although their crystalline notes may not be “accurate” in the Western sense, they are in perfect harmony with the powerful voice of the singer and sustain the voice with an unflagging rhythm. The voice states the theme and then improvises upon it in an utterly enchanting manner.

We have already described the mvet harp-zither in the chapter dealing with the African musician (see page 29) and so we will at this point merely remind the reader that it is an instrument with plucked strings. A detailed description of the instrument has been given by the Cameroonian musicologist, Eno Belinga, in his book, Littérature et musique populaire en Afrique noire (Popular Literature and Music in Black Africa).37 As we mentioned previously, the repertoire of the mvet consists mainly of epic or lyric stories of cosmogonic dimensions. A knowledge of these tales is indispensable to any non-African who wishes to understand African Negroes.

The mvet plays a primordial role in the art of relating these legends. The introductory music played by the musician-narrator-dancer on the mvet elicits silence from the assembled listeners. The instrument accompanies the entire story and provides musical interludes when the weary narrator wishes to take a few minutes rest. These interludes, in fact, reveal that the musician attributes the same degree of importance to the music as to the story and treats them as equals. He shouts to the crowd of listeners who are hanging on to his every word, “Men, women, brothers, and sisters—what are your ears listening to?” As if one man, the audience roars back, “They are listening to the mvet.” Then, the harp-zither becomes the centre of attention and as soon as it is begun to be played, it is joined by an impromptu rhythm section, consisting of an empy bottle that is struck with a large iron nail and with one or more wicker rattles. Although the mvet’s musical possibilities are limited, it largely compensates for this by its personality and the importance it has vis-à-vis the audience.

We have already quoted an extract from one of these stories with mvet accompaniment (see page 29),38 but we thought that it would be interesting to give the translation of another epic from south Cameroon, the tale of Engonezok. Mr. Eno Belinga introduces the record in these words: “A brilliant interpretation which gushes forth among the enraptured audience like an impetuous torrent into a valley. Everyone is hanging on the lips of the zithertoucher, whose tall black silhouette stands out against the dark background of the hut, enveloped in the mysterious black veil of night. Osomo the mbom-mvet sings and declaims the noble deeds of the race of Ekan-Nna-Mebe’e.”39 Here is the translation of the recorded extract of the epic:

My tale will not be confined to the mere dispute

Between a citizen of Engonezok and the inhabitants of Ntui;

For there is a far more memorable deed

And I shall now tell you what occurred at Engonezok.

Listen carefully! As you know, it all started

When Nnomongan began to sound his horn

At the hour when the birds, the messengers of dawn,

Burst into song. Nnomongan was in the courtyard.

He swore by all the dead and blew his horn.

As soon as the sound of the horn was heard

The woman who was the wife of Ondo

Felt sharp pains and pangs in her belly.

The wife of Medan felt the same atrocious convulsions,

And the wife of Meye-me-Ngi in turn was seized by the same agony.

Prostrate, racked with the pangs of childbirth

The three wives cried out in their nameless pain.

Suddenly—one!—the wife of Ondo

Gave birth to a male child;

And—two!—the wife of Medan

Gave birth to a male child;

And—three! The wife of Meye-me-Ngi

Gave birth to a male child.

And so it happened that, at almost the same moment,

Three male children were born in Engonezok.

A few minutes later,

Just after the birth of these children,

Nnomongan, the man who initiates into the Mysteries,

Was quite amazed to hear in the clear morning:

“Tu-gu-du-gu-du-gu-du-gu”:

The tom-tom announcing its happy news;

Ondo, the father of one of the three children,

Was telling everyone, with beat of drum,

Of the spectacular birth of his son.

Then the tom-tom played the signature tune

Which was Ondo’s motto and crest:

“Without nephew or maternal uncle,

Ondo trembles, Ondo rejoices, Ondo is full of joy

And his wife, the daughter of Ndongo,

Radiant as the full scarlet moon,

Has just given birth to a male child.”

Nnomongan was still listening when a second tune

Was heard on the drum:

“Medan, with insolence on my brow,

Seated like a lord on my throne of valour and bravery,

Twisted like a knot, Medan

The grandson of Ekan-Nna-Me be’e,

Superior to all, for fortune and I are one,

My wife, beautiful as a lake,

Bright and refreshing as spring water,

Has just given birth to a male child.”

Nnomongan was perplexed; and just then

A third signature tune was heard on the drum:

Kora harp-lutes (Senegal )

Since he elected to live in these parts

To the east of his fields and his lands,

Friendless, unloved by a living soul,

Meye-me-Ngi, who inherited a tree-trunk

From his father, floating on the abyss of life,

On the crest of the wave where the electric fish swims

From whence one fine day he drew forth

A goodly supply of sabres and machettes,

My wife has just given birth to a male child.

Tu-gu-du-gu-kpwo!”

Nnomongan, his heart beating with terror, leapt up

And, after putting into his game bag the mysterious stone

Which he had gone to seek in the abode of the dead,

Went straight to Ondo’s house and asked him:

“Why are you beating your tom-tom?–

“My wife,” replied Ondo, “has just given birth

To a male child.”

“Take me to this child at once; it’s an order.” When they got inside the hut

They saw the baby crying, “Nyan-nyan-nyan-nyan.”

Turning to the mother Nnomongan said,

“Woman, you are indeed beautiful, daughter of Ndongo,

You are as radiant as the full scarlet moon.

May I look upon your illustrious baby?”

Nnomongan took the illustrious baby in his arms,

And turning to the father, he said,

“You wished that your wife would never bear

A child in her womb; didn’t you know

That one day an illustrious descendant would

Be born in Engonezok? And today you dare pretend

That this child is yours … I tell you,

You are an insult to our race.” Then Ondo

Excused himself and said,

“Forgive me, it’s true, I did say such things.”

But suddenly Nnomongan put the baby in his bag

And drew out a copper jewel: at that moment

The father of the child took fright and shouted,

“Nnomongan, where are you taking my son?”

As though by magic, the shadow of Nnomongan vanished

And disappeared like a dream.

“Tu-gu-du-gu-du-gu-du-gu-du.”

Ondo set off in pursuit

But could not seize the impalpable shadow of Nnomongan.

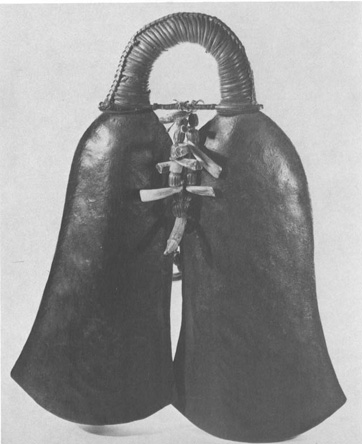

Mvet harp-zither (Cameroon )

He crossed the yard, but saw no-one.

Ondo went up to the sky,

Looked in the clouds and still saw no-one,

Nnomongan was already far away in the East,

In the spheres where the sun lights up each day.

Nnomongan went to Medan Endon’s house.

He stole the child and took it off in his bag.

Then he went to Meye-me-Ngi. He stole the third baby

And took it off in his bag. Nnomongan,

The master of initiations, went up to the sky

And then went home. He entered, closed the door

Nine times with padlocks, crossed a dark room

And came to the magic bath

Where the Mysteries bathed; he took the three babies

And put them into the bath: and then, once more, he sounded his horn.

After which, he made an invocation:“Oh ancestors,

The power of mortals has its bounds. Oh fathers,

Meme’e m’Ekan, Ngeme-Ekan, Oyono-Ekan,

The three babies are waiting in the bath of Mysteries.

Tell me now, who on earth is going to keep an eye on them?”

The mvet harp-zither is found mainly in south Cameroon, in the north of Gabon and Congo-Brazzaville, and in the Central African Republic. It is not solely used to accompany epic narrations but may also be used simply to accompany recitatives or songs.40 Another type of harp-zither, found in the Congo and known as the Mboko , is unusual because instead of a sound-box that is made from a half-calabash, it has a sort of small, plaited-bamboo mat that is level with the bridge. Finally, there are harp-zithers with no sound-box at all, such as those sometimes made by the Pygmies of the tropical forest.41 The mvet of the Fang tribe (south Cameroon and Gabon) usually has four strings. They are raised from the palm stalk that composes the body of the instrument and they pass over a bridge that is fixed half-way between the two ends of the stalk. The ensemble of the strings is thus divided into two sets, providing four notes for each hand. These notes sometimes have specific names, as for example, those given to the sounds produced by the Fang mvet that is tuned to accompany the epic of Akoma Mba. The Western notes that are indicated in brackets are those that come closest to the actual sounds, but they are nevertheless only approximate.

left hand: Ekang Na (E)—Na Mongom (D)—Evini Tsang (C)—Akoma Mba (A)

right hand: Ntuntumu Mfulu (C)—Engwang Ondo (B or Bb)—Medang Boro (A)—Medza Motugu (F).

Another member of the stringed instrument family of black Africa is the bow-lute. A bow-lute has a sound-box with several wooden bows imbedded in it; these hold the strings. The bow-lute is among the oldest known traditional instruments; its existence is mentioned in various travel journals dating back to the sixteenth century. It is quite certainly the ancestor of the Ngombi bow-harp from the Central African Republic and other similar harps. In its most developed form, where the bows are not separated but joined by raffia links, it certainly recalls the shape of a harp. The only difference is that the plane of the strings is not perpendicular to the top of the sound-box. The bow-lute is commonly used by forest walkers in maintaining a regular rhythm and very often it accompanies the incantations of magicians, especially medicinemen.42

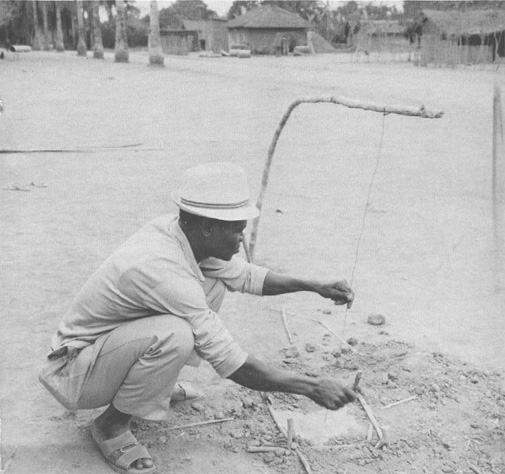

The earth-bow—a curious voice that seems to emanate from the earth

There are several types of musical bow in black Africa. Those that have been recorded so far are the earth-bow, mouth-bow, and resonator-bow.

The earth-bow consists of a flexible wooden pole planted in the ground. A string is stretched from the upper end to a small plank or piece of bark that covers a hole in the ground. The hole acts as a resonator. When the string is plucked or struck, the sound apparently emerges from the bowels of the earth. This explains why it is much used in magic.43

The mouth-bow is a wooden bow with one string stretched between the two ends and is struck with a stick. The musician places the string between his parted lips so that his mouth acts as a resonator. The sound can be amplified or diminished by opening or closing the mouth. The pitch is varied by means of a touch that is moved along the string with the left hand.44 Sometimes, a musician will sing and simultaneously accompany himself on the mouth-bow in a curious kind of dialogue in which he takes both parts.45

The resonator-bow is a variation on the mouth-bow, however, it has the addition of a calabash resonator that is placed in the middle of the bow. In Rwanda, where it is fairly widespread, it is called Munahi . The instrument is also found in Dahomey and is call the Tiepore . The same instrument in Madagascar is known as the Jejolava bow.46

This group of instruments is fairly well-represented in black Africa, although some of them are limited to a very narrow geographical area. Whistles, mirlitons , flutes, trumpets or horns, clarinets, and oboes are all played in one or more parts of the continent. One general remark applies to this group; unlike instruments of other categories, absolutely no attempt is made to modify their timbre. The curious timbre of the mirliton —thanks to which it plays an important role in music and in society—is not due to any intentional acoustic experimentation. The sonority of the flute is universal. The alghaita happens to have the timbre of an oboe and no artifice is employed to alter it in any way. Simlarly, most horns and trumpets emit completely unaltered sounds, in contrast with lutes which are often equipped with jingles, or with certain percussion instruments equipped with resonators. These horns and trumpets are usually beautifully carved and often rank as genuine works of sculpture.

Mirlitons are found in a good many African communities, either as children’s toys or as instruments for the use of adults in certain rituals. The mirliton which features in the ritual ceremonies of the Dan —a tribe which straddles the western frontier of the Ivory Coast with Liberia—has attracted the attention of many investigators and has been recorded several times. It consists of a hollow bird bone, one end of which is stopped with a spider’s web membrane. The other end, the part held in the mouth, is left open. When the player talks or sings with this mirliton in his mouth, the membrane vibrates and “masks” his voice. In other words, it is an “acoustic” mask. TheBaegbo mask is comprised of five young men playing mirlitons of this type. They perform as a unit which is considered as a single mask and, although it is not the usual type of mask that is worn, women and girls are not permitted to see it. Hence the Baegbo is only formed at night and outside of the village. In former times, this mirliton-mask wielded enormous power. It was the vehicle of punishment for any man or woman who had broken the law or failed in his or her duty to the community. Today the Baegbo is usually just a means of entertainment for young people.47

Necked whistle (Dahomey )

Whistles may be used to mark the rhythm for dancing, but as each whistle produces only one note, their use is somewhat limited. Sometimes, however, they are formed into orchestras. Each whistle plays its own note at a given moment in the ensemble in order to produce a melodic line. The complexity of this type of music is quite astonishing. The whistle may also be used concurrently with the human voice; the musician sings a tune that is punctuated at regular intervals by the sound of the whistle. This is a common practice in Pygmy music.48

The flute is always a delightful instrument and the music of the African flute is particularly accessible to non-African ears, mainly because it has a universal timbre. One of the three varieties of flute—vertical, oblique, or transverse (panpipes are unknown in Africa)—is the constant companion of every shepherd49 and cowherd. Whether in solo or duet,50 they produce a variety of charming melodies that may be slow or fast and light, philosophical meditations or satirical tunes.51 The number of finger-holes varies between two and six in different regions. The Fali of northern Cameroon, for example, use a vertical, notched flute with four finger-holes called Feigam . 52 But without any doubt the most beautiful flute music is that of the Fulani shepherds who achieve exquisite results with an instrument that is simply a length of reed.53 Flute duets are often seen as a symbolic representation of the couple, the genesis of life, and the music they produce is considered symbolic of the fruit of their union.54 Consequently, there are male and female flutes, the latter generally being smaller in size. As in any marriage, there are times when man and wife disagree. An argument may then ensue between the male and female flutes, but instead of bittersweet words, there is music, which despite the storm, is no less charming to the ear.55

Finally, as in the West, the flute can be used in instrumental ensembles. It can usually be distinguished from the other instruments by its characteristic timbre, making it the most universal instrument in all African music.56

Ivory transverse horns (Ivory Coast)

In different parts of the continent, trumpets, horns, or even elephant tusks are also used to provide musical sounds. Most of these trumpets are animal horns, but in some areas they are made from wood or metal; such a trumpet is the Kakaki played by Hausa musicians from Niger, Nigeria, north Cameroon and Chad. The Babembe of the Congo make trumpets in human likeness; they are huge instruments with a dorsal mouthpiece and an open base. Most wind instruments have a very limited register, restricted to one or two notes. In Dahomey, the Berba use transverse horn trumpets that have a lateral opening through which the player blows; a hole at the opposite end can be stopped with the index finger.57 The Baule of the Ivory Coast use the Awe trumpet as the voice of the male genie, Goli, when he emerges from the forest during the funeral of a farmer.58 A Broto trumpet orchestra (Central African Republic) comprised of four small horn trumpets and eight large wooden ones has been recorded.59 This is initiation music which sounds not unlike jazz, being slightly reminiscent of the brass section of Duke Ellington’s orchestra, for example. It begins with an introduction, a kind of call that is played twice in succession by a small trumpet and is answered by the whole orchestra. Then, the other trumpets make their entry one by one and play together for a while. A melodic line is achieved by the dexterous combination of the single notes that are produced by each instrument. A high-pitched trumpet announces the end of the piece; then, the entire orchestra answers this solo. Finally, a second call, followed by an ensemble response, brings the piece to a close.

The Truta trumpets of the Dan (in Dan language tru means trumpet) are similar to the Congolese ones mentioned earlier; both types are made of ivory. The Truta are transverse trumpets and once again they perform in an ensemble where the music consists of the successive emission of the trumpets’ respective notes. An orchestra of this kind, composed of six transverse trumpets (five of which are different in size) has been recorded.60 The lowest and the highest trumpets produce two notes each, the rest produce a single note. The dancers who encircle the musicians sing certain tunes, pronounce names, or recite proverbs to inspire a particular piece of music; subsequently, the trumpets begin to play this music as though in answer to the dancers’ invitation. In former times, these orchestras of ivory trumpets belonged exclusively to chieftains and were used to play court music in their honour. They were also used to encourage warriors going into battle or to greet them on their victorious return.

Another trumpet orchestra has been recorded among the Babembe in the Congo. This orchestra consists of four trumpets in human likeness, representing four people: father, mother, son, and daughter. The first three are held vertically, the fourth horizontally. The music played by this orchestra is connected with ancestor worship.61

Oblique flutes (Niger )

Bamileke carved ivory horn (Cameroon )

There are numerous other varieties of trumpet in West Africa. Generally speaking, they are made from calabash. In northern Cameroon and south-west Chad, for instance, there is a trumpet known as the Hu-hu . It can be used either as a proper musical instrument (the musician blows into the mouthpiece and uses his lips as a reed to produce sounds) or merely as a loudspeaker. The Hu-hu62 consists of a long tube attached to a bell; both are made of calabash. The player frequently holds it in one hand and shakes a calabash rattle with the other, but this is not a general rule.

The calabash bell is sometimes attached to a horn or wooden tube. This type of trumpet, which may be vertical or transverse, is sometimes fitted with a sort of appendix, a small supplementary tube which communicates with the main tube at the level of the mouthpiece. When the instrument is played, this supplementary tube is alternately stopped and opened with one finger. In addition, the main tube may be equipped with one or more mirlitons —yet another example of the quest for timbre which is so characteristic of African music.

Among the Tupuri of south-west Chad, a region known as Mayo-Kebbi, trumpet orchestras made up of up to ten wind instruments of various types may be heard at harvest time.63

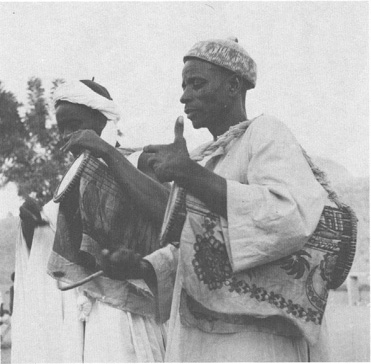

The Kakaki is a man-made trumpet whose chief exponents are the Hausa people of Niger, northern Nigeria, Chad, and the north of Cameroon. It is a tin trumpet which can measure up to 9 feet in length. It consists of two distinct parts that are slotted together: a conical bell, some 4-6 inches in diameter and about 1 foot, 6 inches high, and a cylindrical body, approximately 1 inch in diameter, widening out to 2 to 4 inches at the mouthpiece. Apart from its remarkable size, the kakaki also possesses an impressive, shattering timbre. Its limited resources prohibit its use as a solo instrument (it produces barely two notes, a fifth apart) but its majestical tone is employed to augment orchestral ensembles. With a few rare exceptions, the Hausa utilize wind instruments exclusively in honour of dignitaries, in particular high-ranking officials of the traditional government. The traditional government of Nigeria has not been abolished or replaced by new national institutions; the Hausa territory in the north is still divided into Emirates, ruled by Emirs. The Sultan is senior to all the Emirs and the band that plays in his honour is composed of the best musicians in the country. The fanfare sometimes played to salute an Emir at dawn also acts as a reveille for the rest of the population.64 The composition of these bands varies, of course, but the “Fanfare for the Sultan of Sokoto” (Nigeria) with its three kakaki , three alghaita (oboes with a single reed), and drums65 is fairly typical.

Babembe horns in human likeness (Congo)

Animal horn used as a transverse trumpet 73

Hu-hu calabash trumpet (North Cameroon) African Music

A musician from Chad playing a Hu-hu calabash trumpet

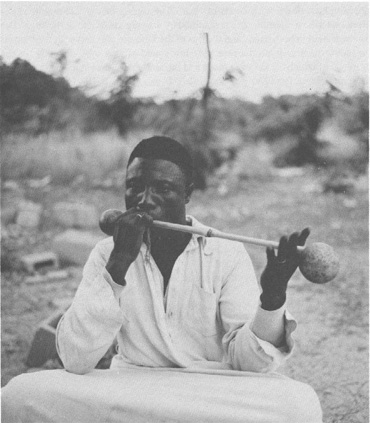

Alghaita oboe player

Most Hausa orchestras are composed of two kakaki , one alghaita and a rhythm section of variable size. The alghaita is a conical, collapsible oboe whose two constituent parts are linked by a tiny chain. A metal tube containing the reed is slotted into a wooden body that is covered with leather. The base of the body, which has four finger-holes, widens out into a bell. The reed (which is literally a piece of reed) fits into the upper end of the metal tube that is immediately above a small iron disc soldered to the tube. When the musician places the reed in his mouth, his lips rest against this disc, which hermetically seals the air reservoir that is constituted by his mouth. Such a technique is aimed at producing a continuous sound that does not depend on the musician’s breathing, but is only interrupted if he so desires. Before beginning to play, he inhales a large mouthful of air and puffs out his cheeks as much as possible. The disc enables him to control the amount of air entering the oboe in order to ensure that the air reservoir never empties; as he plays he continues to breathe in through the nose so that the volume of air in his mouth remains constant. This system enables the alghaita to be played without any interruption for hours on end, rather like bagpipes. This characteristic is evident in most alghaita recordings.

No less remarkable are its amazingly voluble improvisations which, because of the piercing tone of the instrument, are set off to advantage in orchestral ensembles. The alghaita always manages to make itself heard through even the most deafening percussion. A Hausa praise song in honour of the Djermakoy (Djerma king) has been recorded in the palace courtyard in Dosso (Niger) in the presence of the Djermakoy himself.66 Like all dignitaries of the Hausa or Djerma societies, the Djermakoy has griots attached to his court and this song, accompanied by an alghaita , is performed by one of them.

An orchestra of flutes ), alghaita, kakaki, and drums

Millet-stalk clarinets

Naturally though, the possibilities of the alghaita and the virtuosity of the black artists who play it are best heard in ensembles. The alghaita is often grouped with three drums and manages to take the preponderant role, whether in improvisations of a rare variety or in dance music.67 The alghaita that is played by the Djerma is larger than that of other tribes, and consequently, it produces a deeper, more powerful sound.68 The virtuosity of the players of this African oboe is such that they even manage, because of a system of phonetic equivalences, to send messages with the instrument that can be decoded by the initiated.

There are two types of clarinet worth noting, namely the Fulani clarinet, Bobal , and an idioglottic clarinet, which is known as Papo in Dahomey and Bumpa in Upper Volta. The Bobal is merely a millet stalk with a slit at one end.69 The Bumpa clarinet that is played by the Bussance in Upper Volta is identical to the Papo of the Dendi (Dahomey) and is also a millet stalk, but has a vibrating reed at one end and a lateral hole at the other. A small calabash that is pierced with several holes is placed at each end of the stalk. The column of air in the stalk vibrates when the musician alternately inhales and exhales through the loose reed; he simultaneously stops or opens the lateral hole with his thumb. The two calabashes modify slightly the timbre and volume of the instrument. Although it is technically a clarinet, it does sound rather like a saxophone. The possibilities of the Papo are such that it may some day be able to broaden its horizons; at the present time, these are rather limited. The music of the Papo is of astonishing beauty and simplicity.70

This clarinet Is known as Bumpa In Upper Volta and Papo In Dahomey .

Two keyboard instruments are used in black African music: the Sanza , an instrument with plucked keys, and the xylophone whose keys are struck.

Some musicologists have claimed that the Sanza is “the only invention that can be attributed to the African Negroes.” We shall not be quite so categorical since our purpose is not to discuss the origins of African musical instruments. We shall merely point out that the Sanza is found in various far-flung parts of the continent. It is known by a number of different names, but even though its external appearance varies, the principle and the technique that is used are invariable. It is usually a rectangular wooden parallelopiped about 9 inches long, 5 inches wide and 2 inches high. These are the minimum dimensions and there are much larger Sanzas that usually provide the bass notes in instrumental ensembles. The sound-box may be in a single block—a piece of hollowed-out wood with an opening at the front or the back that acts as the sound hole—or in several pieces of wood, bamboo, or palm stalk that are joined together.

A number of keys made of narrow strips of bamboo, bark, or metal are fixed to the sound-board and attached to the back of the bridge, either separately or all together. The tips of the keys, which are suspended over the sound hole, are weighted down with beads of resin. The tuning of the instrument varies from one tribe to another, and is obtained by varying the length of the keys. The Sanza is held in both hands and the tips of the keys are plucked with the thumbs or index fingers. It produces a pleasing sound whose tone depends on the material of which the keys are made and the amount of resin stuck on the tips. It is sometimes referred to as “the little African piano”. 10, 16, 20, 26, and sometimes even 30 keys afford musical possibilities that can be enlarged by associating several instruments of the same type; two or three Sanzas are often played together. The large Sanzas are classed as percussion instruments with variable sounds and generally have a maximum of five keys.

Sanza, Sanzi, Sanze and Sanzo are variations of the same instrument. It is also called Likembe or Gibinji in the Congo; Timbili by the Vute (or Babute ) of Cameroon; and Deza by the Lemba of the Transvaal in South Africa. In Upper Volta, the Bussance know it as the Kone . Other versions may also well exist.

The Sanza is above all an instrument used for relaxation and recreation. Many nightwatchmen in the commercial areas of African towns play the Sanza to make the long night hours “pass more quickly.” It is also a popular instrument for people making long journeys on foot through the forest and could be termed, “the walker’s friend.”71 It can be played as a solo instrument or can accompany vocal or choral music; it is also found in orchestras. There is a beautiful recording of the Kone Sanza (made in the Bussance region of Upper Volta)72 that could almost be taken for modern jazz; the successive rhythms, the phrasing and polyphony, even the tone of the instrument, could be compared to the vibraphone playing of someone like Milt Jackson. A Bagandu Sanza and xylophone duet and a satirical song with Sanza accompaniment (both recorded in the Central African Republic)73 give some idea of the various combinations obtainable with this little instrument.

Kone Sanza (Upper Volta )

But the Sanza is not merely an instrument of recreation. In some regions, it has an important symbolic role that cannot be overlooked. The Lemba, a Bantu tribe from the Transvaal, consider the Deza Sanza as a sacred object. It represents the Lemba ancestors and enables them to be reincarnated through the medium of dancers, etc. Its physical appearance and the materials from which it is made, as well as the music it plays, are strictly governed by initiation laws that are associated with the python myth. One manifestation of this myth is the Domba or python dance, “a fertility rite in which young men and girls fresh from their respective puberty schools come together to follow a joint course of instruction in preparation for marriage.” During the dance, the instructor sings while the novices link arms and dance; they simulate the slow movements of an uncoiling python. In this society, the python is directly linked with female fertility; a sterile woman wears a python skin around her neck and back in the hope of becoming fertile.

This belief arises from a legend that usually runs as follows: “The python took a second wife who did not realize that he was a python. At night, she felt something cold sliding towards her, but when she asked what it was, the python told her to be quiet. In the daytime, she used to go and work in the fields with the first wife. She was curious to see her husband and tried to find pretexts for going back to the village, but the first wife always prevented her. One day, however, she pretended to have forgotten her spade and went back to the village where she saw the python sitting in the men’s courtyard, quietly smoking his pipe. He was so furious that she had seen him that he rushed off and disappeared into the depths of Lake Fundudzi. Then the rain stopped falling; the crops withered; a great famine reigned throughout the land and all the streams dried up. The divining bones were consulted and revealed that the disappearance of the python was the cause of the trouble; he wanted his young wife to go and join him at the bottom of Lake Fundudzi. The people were immediately called together and the royal princesses began preparing the ritual beer, mpambo . When the mpambo was ready, everyone went down to the lake; the men were dancing and playing the tshikona , an invocation to the ancestors of the tribe, while the women carried the mpambo . The python’s wife was hidden in the midst of the crowd and could hear nothing but the sound of the Tshikona flutes. When they arrived at the lake, they offered the mpambo to the python in propitiation and the young woman, holding the gourd of beer in her arms, went into the water and disappeared into the depths of the lake to join her husband. And the rain began to fall …”

This is the reason that each year a young Lemba girl must disappear into Lake Fundudzi in the Northern Transvaal in order to join the python and bring rain. As far as we know, the sacrifice still takes place today.

Initiation into the Domba rite is, therefore, an event of major importance for the Lemba tribespeople. Every initiate spends several months dancing the python dance—a dance that imitates the uncoiling of the python—singing “Tharu ya Mabidighami” (“the python uncoils”) and learning the Domba laws. Such an initiate thus comes to understand the origin of the myth, “In the beginning mankind and the whole of creation were seated in the belly of the python; one day he spewed them forth.”

The Deza Sanza , with its 22 keys, contained in a hemispherical calabash resonator, actually represents the whole of creation and mankind that is seated in the python’s belly. The striking of the notes to produce sound is truly an act of creation—the birth of a child who cries; the wooden frame represents the women who have come to assist at the birth. Every single component part of the Deza is symbolic: the calabash resonator is the womb; the sound, as we have just explained, is the child that is born; the string that is tied around the calabash represents the python skin that encircles the village; the keys are the people who are seated inside the python—8 men (the high notes), 7 old women represented by copper keys (copper being the metal of the womenfolk—the Lemba consider red to be a feminine colour); the hole in the rectangular sound-box is the deflowered maiden, and so on.

Deza Sanza of the Lemba (Transvaal )

A. The keys of the Sanza represent the men seated In the python’s belly (22 notes ).

B. Calabash—the womb

C. The sound-hole symbolizes the deflowered maiden .

D. The Sanza fixed Inside a calabash; the frame represents the women who have come to help the young woman In labour (to pluck the keys Is to create—the sound Is the child being born ).

E. String tied round the calabash representing the python skin encircling the village

So the Deza Sanza is a musical instrument that not only represents the creation of sound and the perpetual renewal of the first creation (when the python vomitted), it also reflects the structure and laws of the society; laws which “Mwari,” the God-Creator, taught the first men who played the Deza Sanza . In short, as far as the Lemba are concerned, the Deza Sanza is synonymous with life.74

There are few African countries in which this instrument does not exist; in some respects it is just as representative of African music as is the drum. The xylophone may be resonated or unresonated, but it invariably has wooden keys that are struck with mallets (also made of wood) with rubber or leather tips. The type of wood varies from region to region; it also depends on the sonority desired; soft, light wood gives a deadened sound, while hard wood renders a crystalline sound. There are virtually no rules as to the choice of material. The number of keys also varies, from three to as many as 17—the number on the xylophone that is used by the Bapende (Congo). The simplest form is the leg-xylophone that consists of three or four wooden bars that are placed cross-wise on the outstretched legs of the musician. Leg-xylophone players often sit on a wooden mortar or some other large object that acts as an amplifier. This is common practice in the north of Togo, in the Kabre area, where the keys of the xylophone are usually comprised of four or five stalks of dried Palmyra palm.75

Log-xylophones are found in the south-west of Cameroon and other parts of Central Africa. Two long banana-tree trunks that are laid on the ground act as supports for some 15 wooden keys. These long keyboards are usually played by two or three musicians and another man, whose task is to supervise the smooth running of the performance, stands facing the musicians and replaces any keys that are accidentally dislodged. The instrument forms part of a traditional dance orchestra, also comprised of mirlitons , whistles, drums, and other rhythm instruments. When the dancing is over, the xylophone keys are removed and the banana-tree trunks are put away in a cool place to keep them in good condition until the next performance. The Azande of the Central African Republic call this type of xylophone, the Kponimbo . There is a recording of the Kponimbo , accompanied by a two-headed drum that plays gbwenlen , a type of dance music that in this instance is played merely for entertainment.76

Log-xylophone (Central African Republic )

Leg and log-xylophones are by no means the best-known examples of this family of instruments. By far the most popular type of xylophone is the Balaphon . Portable or otherwise, these xylophones have calabash resonators that vary in size according to the pitch of the notes desired. The resonators are fixed under the keys, which are attached to a rectangular frame by a long piece of string. There is a hole in each calabash that is covered with a mirliton and attached with resin. The mirlitons may be made from a spider’s web, a thin piece of fish or snake skin, or a bat’s wing. These mirlitons give the Balaphon its characteristic timbre, which is quite unlike that of the similar instruments that one encounters in South American Negro music. The African xylophone is the ancestor of the Latin American marimba; the large xylophone with 17 keys that is used by the Bapende in the Congo is called Madimba . Such a term leaves no doubt as to the origin of the Latin American instrument. In some countries, Balaphon players wear on their arms metal bells whose jingling adds an extra sound to the music.77

Senufo xylophones and drums (Ivory Coast )

There is an abundance of xylophone recordings of many kinds, ranging from solo performances to the xylophone orchestras that exist in various regions of black Africa.78 There are also all sorts of interesting combinations, such as a beautiful example of Bagandu music (Central African Republic) with a xylophone and Sanza duet; the two instruments blend perfectly and they simultaneously produce unexpected rhythmic effects.79 Examples of this are an excellent xylophone and Kora duet from Senegal80 and a duet for xylophone and voice that is performed by a blind musician from Upper Volta who is an extraordinary virtuoso and singer.81

In some parts of Africa, xylophones were used in divination rites. The xylophone, together with a small wooden drum with no membrane, accompanied the chanting of a fetisher, while he tracked down wrongdoers or healed the sick. Now, Balaphons are usually played for entertainment purposes and it is not uncommon to see village squares or town market places filled with large crowds who gather around the Balaphon players for the mere pleasure of dancing.

On such occasions, certain tribes of equatorial Africa single out as the main attraction two or three very young girls who dance with all the elegance, grace, and technical ability of confirmed stars. The mendjang dance of the Fang of south Cameroon and north Gabon is a typical example. Confining the leading role to little girls is a reminder that in former times it was mainly the Pygmies—or little people—who were the star performers. Another interesting feature of this dance is the special use of the instrument that “converses” with the dancers. The mendjang orchestra of the Fang consists of at least four or five xylophones and sometimes percussion instruments are added—single or double iron bells, rattles, etc. The xylophone ensemble forms a keyboard of 30 to 40 wooden keys that cover a range of more than three octaves. The orchestra and dancers are ready and the village square is packed. One of the xylophones, usually played by the group leader, begins with a short prelude. Thus, he requests the audience to be silent and warns the dancers to get ready. After this introduction, a “conversation” begins between the instrument and the dancers, along the lines of the following, which Mr. Herbert Pepper recorded among the Fang people of Gabon:82

Xylophones with curved keyboards (Upper Volta). The calabashes act as the soundbox of the Instrument .

After this verbal game, the other xylophones join in so that the young dancers can show off their talents. Needless to say, these games have a vast repertoire that range from proverbs of great wisdom to the most trivial events.

Layers of rhythm rising upwards from the ground

These Guinean xylophones have no calabash resonators to amplify the sound.

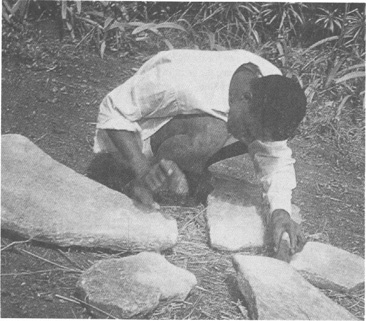

Lithophones are a very particular type of instrument and they are limited to certain parts of black Africa, such as the north of Togo and, in quite a different form, in northern Nigeria. A lithophone is a group of basalt stones. When struck, these produce sounds that can be incorporated into a piece of music. The shape and size of the stones vary considerably. In the Kabre region of northern Togo, the instrument consists of four or five flat stones that are arranged in star formation on the ground or on a bed of straw. The musician hits them with two stone strikers; the striker that is held in the right hand usually plays the tune, while the other punctuates the musical phrases or taps out the rhythm on the largest stone, which has the deepest or most neutral sound. Every Kabre family has its own lithophone, which is usually played by the young boys. Based on the farming cycle, this music has a marked seasonal character. For instance, in the first days of mid-November, the lithophone is played to mark the end of the rainy season and in December, it announces the feast of the millet harvest. The instrument must not be played after the millet harvest. Each agricultural feast has its own particular music that may not be played at any other time. This taboo is scrupulously respected because the farming rite is closely connected with the cult of the dead and the dead have the power to fertilize the soil and make rain.83

Kabre lithophone (Northern Togo )

Giant lithophones exist in northern Nigeria, chiefly in the regions of Kano and Jos. These lithophones are composed mostly of groups of rocks that have been found in natural formation. The music they produce is still used in some villages for initiation and circumcision ceremonies or for certain religious ceremonies. As in northern Togo, there is a similar relationship between the lithophone and farming. In and around Nok, the sound of the rocks can be heard before the first harvest of the year. Single girls take seeds and crush them on the large sonorous rocks.

In Kusarha, near northern Cameroon, the lithophone is used as a means of communication with the spirits whose voices can be heard echoing from the caverns in the rocks.

In the past, the main use of the lithophone in northern Nigeria was to warn of an enemy approach in time of war. This was the method used in the nineteenth century to signal the arrival of the Fulani horsemen who were advancing across the plain some 3 to 4 miles off and were bringing the Holy War. These days, lithophones are also used to accompany dance music.

The lithophone concludes our inventory of melodic instruments. Drums and other percussion complete this survey of African musical instruments.

It is scarcely necessary to emphasize the importance of drums in African music. These instruments are considered throughout the world to be the most representative African instruments; and for many non-Africans, they are the only ones. The preceding pages have shown the error in such a judgment. Yet, the drum is, without question, the instrument that best expresses the inner feelings of black Africa. These drums possess a vast range of materials, shapes, uses, and taboos. They have remained constant throughout the ages and they are extraordinarily popular throughout the continent. Even outside of Africa, on their long journey of expatriation (during the evil days of slavery and after), they have managed to adapt themselves to conditions of life totally different from those on the black African Continent. They epitomize the real definition of African music—a music that speaks in rhythms that dance. No genuine African music is an exception to this definition and the reason for this fact lies in the omnipresence of drums in the Negro musical world. Even when the drum itself is physically absent, its presence is reflected by hand-clapping, stamping, or the repetition of certain rhythmic onomatopoeias that are all artifices that imitate the drum beat.

But to the Negro, music and speech are often synonymous. Here too, the drum finds its rightful place, a place of honour that enables it to participate in all ceremonies that mark important stages in a man’s life (cf. the remarks made on page 10 about the initiation ceremonies of the Adiukru of the Ivory Coast).

Baule percussion (Ivory Coast )

And even on less solemn occasions, the voice of the drum is employed—to communicate a piece of news or to send a message from one village to another. The art and technique of the drummed message achieve a very high degree of competence. But not all Africans can understand or transmit messages with the aid of a drum; it is a skill that requires a patient apprenticeship.

The instruments that are used and their techniques, as well as the forms of language transmitted, differ from region to region. The Yoruba of Dahomey and Nigeria, for example, use a small, two-headed hour-glass drum. The instrument is held under the armpit and is struck with a hammer-shaped stick. Variations in the tension of the skins are obtained by exerting pressure with the forearm on the longitudinal thongs that connect the skins; this gives different sonorities which can reproduce all the tones of speech. This hour-glass drum (Tama to the Wolof, Kalengu to the Hausa ) sends actual spoken messages; that is, the musician regulates the pressure with his forearm so as to reproduce notes that correspond to the register of the word that he is transmitting. This method of playing spoken phrases on a drum is particularly appropriate in the case of tonal languages, such as Yoruba or certain Bantu languages. Thanks to the varying pressure of the forearm, it is possible to reproduce all the nuances of the spoken language—including slurred notes and onomatopoeias. There are, of course, a number of words with identical musicality and, in order to avoid confusion, a type of code has to be agreed upon between the player and his listeners. The language played on the hour-glass drum, however, is relatively straightforward in comparison with certain other forms of drummed message.

Griots playing hour-glass drums

In fact, the hour-glass drum is unknown in many countries and another type of drum is used for the same purpose. It is made from a length of hollow tree trunk and has no skin. The tree trunk is carefully and skillfully hollowed out, leaving a cylinder with a longitudinal slit with two tongues, one male and one female.84 The tongues are of unequal thickness so that they produce different notes. The average slit-drum is about 3 feet long, although it can range from a minimum of 1 foot, 6 inches to about 7 feet. The diameter is usually somewhere between 8 inches and 1 foot, 6 inches, but it can be as much as 3 feet. The slit-drum can produce only two notes or, very occasionally, three. For this reason, the messages are nearly always coded and consist of a series of metaphorical phrases that can be applied to various events of a similar nature. For example, the arrival of white men, policemen, or other strangers in the village is signaled by the set phrase, “They are here … they are here”; similarly, when the fishermen return with their catch, the news is invariably announced with the message, “The carp is here … the carp is here … It wants money … it wants money,” and the prospective customers rush to the river bank where a canoe filled with dumb but greedy carp is waiting.

A family of drums: father, mother, son, and daughter (Ghana )

Some slit-drums are given proper names, usually consisting of a proverb, symbol, or riddle: “Pain doesn’t kill,” “Death has no master,” “The river always flows in its bed,” “You can’t fight a war with one arm,” “Birds don’t steal from empty fields,” “Do you know what goes ‘thwack’?” (answer: “A whip on the backside”). The real purpose of these names is not just to identify the instrument, but also to confer upon it the virtues that they describe or to remind the musician and his neighbours of the truths and moral precepts on which everyday actions should be based. Occasionally, the name is a reminder of the circumstances under which the drum is to be played; the drum which announces happy events is not used to spread news of deaths and “Dancers, get in line” would be the name of an instrument used to introduce dances.

Slit-drum with carved ends (Cameroon )

A wrestling match In Zigulnchor (Senegal )

Although the slit-drum is best known to Africanists as a means of telegraphy, it is also used as a musical instrument to accompany dancing. Hence, the following riddle that covers both these aspects: “I’ve got a dead prisoner at home, but when I want him to he can talk to people all over the country, or sing to encourage them to dance. Who is he?”

Bantu wrestling matches are always preceded by dancing. Two opposing teams are about to meet. Before they take their place in the crowded village square, the respective champions dance to the rhythm of the slit-drums, which simultaneously sing the praises of the dancers: “Champion, have you ever met your match? Who can rival you, tell us who? These poor creatures from Bassem think they can beat you with some poor devil they call a champion … but no one could ever beat you …” This is played by the drum of one team. The musicians belonging to the rival camp hear and understand these insults and their own drum quickly finds a reply: “The little monkey … the little monkey … he wants to climb the tree but everyone thinks he’ll fall. But the little monkey is stubborn, he won’t fall off the tree, he’ll climb right to the top, this little monkey.” And the drums will go on enlivening the proceedings throughout the entire wrestling match.

When the festivities are over, slit-drums and drums with skins are put away in special places prepared for that purpose (drum huts, the Senufo sacred wood, etc.); these places are not accessible to all. There is an atmosphere of magic in these places and the drums are revered as supernatural creatures. Some instruments are only removed from their hiding places very briefly on rare occasions. The Kuyu of Congo-Brazzaville bring out the seven sacred drums of the Ikuma sect exclusively for burials. They are played from the moment that they emerge until they go back into hiding after they have accompanied the incantations at the burial place.85 When this short period is over, they retreat into their customary silence. In the Dogon territory of Mali, drums play an equally functional music during the dance of the Kanagas . In this dance, huge cross-shaped masks that represent the crocodile on whose back the ancestors of the Dogon crossed the River Niger to settle on the cliffs of Bandiagara (where their descendants live to this very day) are used.86

It would be impossible in such a brief study to enumerate all of the occasions when drums are used and the roles that they fulfil or even to attempt to describe them all; justice could not be done to their astonishing variety in a rapid inventory. Therefore, we shall make a limited selection based on the best available recordings of drum music that will give a faithful picture of one of the most characteristic aspects of African life.

Hour-glass and slit-drums with their variety of sounds are, as we have just seen, commonly used to transmit messages. But whereas the range of hourglass drums is theoretically infinite due to the pressure exerted on the thongs, the slit-drum is restricted to two or three notes. As though to compensate for this, the Malinke musicians of Guinea, Mali, and parts of Senegal have invented an instrument known as the xylophone-drum, which has more than three notes. The xylophone-drum consists of a fairly long piece of hollow wood with longitudinal grooves of unequal length. Each pair of grooves forms a key and each key emits a different note when struck. It is, in other words, a tubular wooden drum with no membrane.

Single-headed drums are also used to send messages in many parts of West Africa. They are a means of communication whose symbolism has not been wasted on certain radio stations. “Progress in the service of tradition” could be the motto of Radio Ghana, for instance, which has for years been announcing its news broadcasts with a recording of these drums … “speaking” English! The signature tune that invites listeners to lend an ear to the news bulletins is played by two drums, with the words, “Ghana, listen … Ghana, listen” (C2 G2 C2 C2 … C2 G2 C2 C2).

Although the principal function of these drums is telegraphy, they are also formed into orchestras. They invariably retain their individual characteristics, however, and produce music in which the rhythm and tone of speech predominate. They are usually six in number, rather like a family consisting of a father, speech tones and are played by a single musician armed with two hammer-like sticks, contribute to the liveliness of the group with their rhythmical phrases. The recording of Yoruba drums played by a group of professional musicians is somewhat similar. This griot orchestra comes from the Oyon region of western Nigeria; this region and Dahomey form the home of the Yoruba . Mr. Gilbert Rouget presents the orchestra in these words:88 “The type of drum ensemble heard here should ideally consist of six drums and two is the bare minimum. The smallest drum provides a continuous rhythmic pulsation to support the second drum (iya ilu: mother drum) which plays a series of rhythmic phrases of varying length that are modified and combined in a multitude of ways, the whole based on the drum language technique known throughout Africa.” Another example is the recording of a Ba-Kongo-Nseke drum ensemble89 who perform a piece of music that is sometimes heard at the end of a period of mourning. The leading drum (the mother) of this ensemble is almost cylindrical and the center of its membrane is covered with resinous paste. The amount of paste regulates the pitch of the drum. The noise of the spherical rattles that the musician wears on each wrist contributes its part to the music. In addition to the “mother” drum, there are two other cylindrical, single-headed drums (without the addition of resin) and all three are beaten with the bare hands.

Dogon drum and Kanaga mask (Mall )

mother, and four children. The Grinpri Senufo percussion band that has been recorded in the Ivory Coast is of this type.87 The central drum is so large that it has to be held at an angle and supported by a stake that is planted in the ground. It has a single head and is played with wooden sticks. This big drum is played only in honour of the chief or other important personalities. “The ritual salutations it raps out dominate the other drums.” Meanwhile, three smaller, one-headed drums play steady rhythmic patterns, reinforced by the chiming of an iron bell. Finally, two one-headed drums that are tuned to two principal