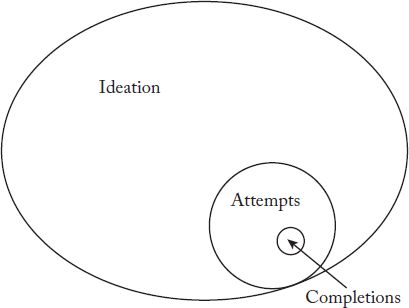

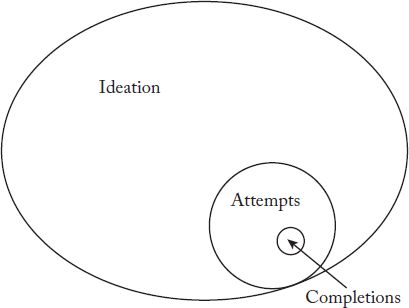

Figure 1. The relationship of suicidal behaviors.

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

I am having trouble deciding were [sic] to kill myself. I can either do it here [home]

when no one is home

call the police before so they can clean up so my family won’t have to discover me

There is a chance the police would get there too soon and save me

My family would probably have very bad memories if they knew I did it in one of our trees

I can do it somewhere else someone would find me, call the police, my family would never see me

This would receive more publicity, which would be shitty for my parents and friends

Even though both are flawed I believe doing it somewhere else is the best option.

The preceding statements were the last journal entry of an intellectually gifted adolescent who completed suicide. It is presented as it was found relative to spacing, spelling, and overall appearance. A few days after writing the entry, the 16-year-old hanged himself in the rafters of the bus stop in front of his local high school. This was the first piece of information that Tracy obtained upon taking on the psychological autopsy of this gifted student.

The death of a child is a parent’s worst nightmare. It represents many of the fears and doubts that raising children today elicit. Many people in society believe that being gifted makes one more vulnerable to suicide. Others believe the opposite—that giftedness provides protection from suicidal behavior. In either case, when a child dies by his or her own hand, nothing creates greater suffering and sense of loss, and nothing is a greater tragedy for society. This book explores the phenomenon of suicide among students with gifts and talents. It attempts to provide the reader a coherent picture of what suicidal behavior is and will clarify what is known and what is unknown about the phenomenon. The book will introduce two major theories of suicide with compelling explanatory power. Information that illustrates the lived experience of gifted students is provided that sets the stage for an emerging model of the suicidal behavior of this population. This model sheds light on the suicidal mind of students with gifts and talents. Based on recommendations derived from traditional suicide research and the research specific to those who are gifted, we provide information on what can be done to prevent suicides among these students. The book ends with considerable resources available to help.

To that end, the book is divided into relatively brief chapters that are based on empirical research, direct observation, literature review, other researchers’ findings and arguments, and a model emerging from years of study. The book represents the level of understanding possible at this time in history. The primary motivation to write this book is to help keep our students alive. With that in mind, information about suicide, description of the lives of students with gifts and talents, and information about preventing suicide are provided.

In addition to raising the consciousness of adults interested in this topic, we will offer a carefully drafted narrative that stays as close to the research base as possible. From this, we hope to raise awareness of the suicidal behavior of students with gifts and talents, spurring additional efforts to be put in place to prevent suicides. We also hope that additional research will be conducted on the topic.

WHAT IS SUICIDE?

To begin, it makes sense to define suicide. Suicide is often defined as a successful act to end one’s own life. It is an intentional act. As simple and direct as it sounds, it has engendered considerable study during the 20th and 21st centuries. Suicide has been acknowledged and written about for thousands of years and its meanings vary greatly based on the cultural context in which it occurs. Durkheim (1951) claimed that “There are two sorts of extra-social causes to which one may, a priori, attribute an influence on the suicide rate: they are organic-psychic dispositions and the nature of the physical environment” (p. 57). From committing hara kiri as an act of taking responsibility for failure, embarrassment, or shame, to dying to avoid responsibility, to dying as a culmination of myriad psychological factors, the context and historical zeitgeist in which suicide occurs matters. This book concentrates on ending one’s life in Western society, particularly in the United States. It emphasizes the phenomenon in the second half of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries.

SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR

If I throw myself off Lookout Mountain

No more pain my soul to bare

No more worries about paying taxes

What to eat, what to wear

Who will end up with my records?

Who will end up with my tapes?

Who will pay my credit card bills?

Who’s gonna pay for my mistakes?

–“Lookout Mountain” by the Drive-By Truckers

A more comprehensive conception of suicide is actually called suicidal behavior and includes three behaviors: ideation, attempts, and completions. The song lyrics above reveal the subject’s thoughts about suicide, an example of suicide ideation. Considerable study has focused on suicide ideation, as it is widely believed by suicidologists to exist in virtually all completed suicides.

Suicide attempts are just that, efforts to die that fail. Completed suicides are defined as killing oneself intentionally. In this book, we use the term completed in lieu of committed when describing suicide. This linguistic change is important, as it reflects the fact that suicides are associated with mental health issues, not legal matters, as it has been considered to be for many years. Moreover, those who work with families of people who have taken their own lives stress the importance of destigmatizing suicide and the descriptor “completed” is both more appropriate and helpful in reducing stigmatization (B. Ball, personal communication, 1992). Another phrase that avoids the appearance of criminalization is “death by suicide.”

Until recently, there was a fourth category of suicidal behavior called gestures. These were originally defined as unsuccessful suicide attempts that were not intended to actually result in death, but some considered any type of failed attempt a gesture (Heilbron, Compton, Daniel, & Goldston, 2010). Such a classification of suicidal behavior proved to be problematic when clinicians or others who might be able to help attempted to interpret “intent”—sometimes concluding the suicidal behavior was simply a cry for help or an effort to manipulate, and therefore, not genuine and less urgent (Heilbron et al., 2010). Eliminating the term from the recommended nomenclature reduces the possibility that any suicidal behavior will be dismissed (e.g., Crosby, Ortega, & Melanson, 2011). Terms such as nonsuicidal self-harm or nonsuicidal self-directed violence are now recommended (Crosby et al., 2011; Heilbron et al., 2010).

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship among the three suicidal behaviors. One of the important ideas being conveyed by this simple figure is that virtually all suicides occur after a person has engaged in suicide ideation. It becomes the background that sets the stage for attempts and completions. Secondly, many more people think about suicide than attempt or complete combined. Finally, there are many times more numbers of attempts compared to numbers of completions. This completion ratio plays out somewhat differently based upon ethnicity and gender and access to lethal means to harm oneself. This book focuses on suicidal behavior among students with gifts and talents. To get to that, however, basic information about suicide in general must set the stage.

Figure 1. The relationship of suicidal behaviors.

KEY POINTS

This book will discuss the phenomenon of suicide in the modern Western society, two major theories of suicide, a new model applied to students with gifts and talents, recommendations for suicide prevention, and available resources.

This book will discuss the phenomenon of suicide in the modern Western society, two major theories of suicide, a new model applied to students with gifts and talents, recommendations for suicide prevention, and available resources.

Suicide is an intentional act of ending one’s own life.

Suicide is an intentional act of ending one’s own life.

The relationship of suicidal behaviors—ideation, att-empts, and completions—was discussed.

The relationship of suicidal behaviors—ideation, att-empts, and completions—was discussed.

Ideation—thinking about suicide

Ideation—thinking about suicide

Attempts—efforts to die that fail

Attempts—efforts to die that fail

Completions—killing oneself intentionally

Completions—killing oneself intentionally