KEY LESSON

Sometimes it’s better to cut your losses than stick it out.

As runners, nothing we do happens in isolation. We train hard this week to be faster next week. We’re wiser today because of learning from past mistakes. And sometimes, what happens during moments of triumph leads to setbacks much later on.

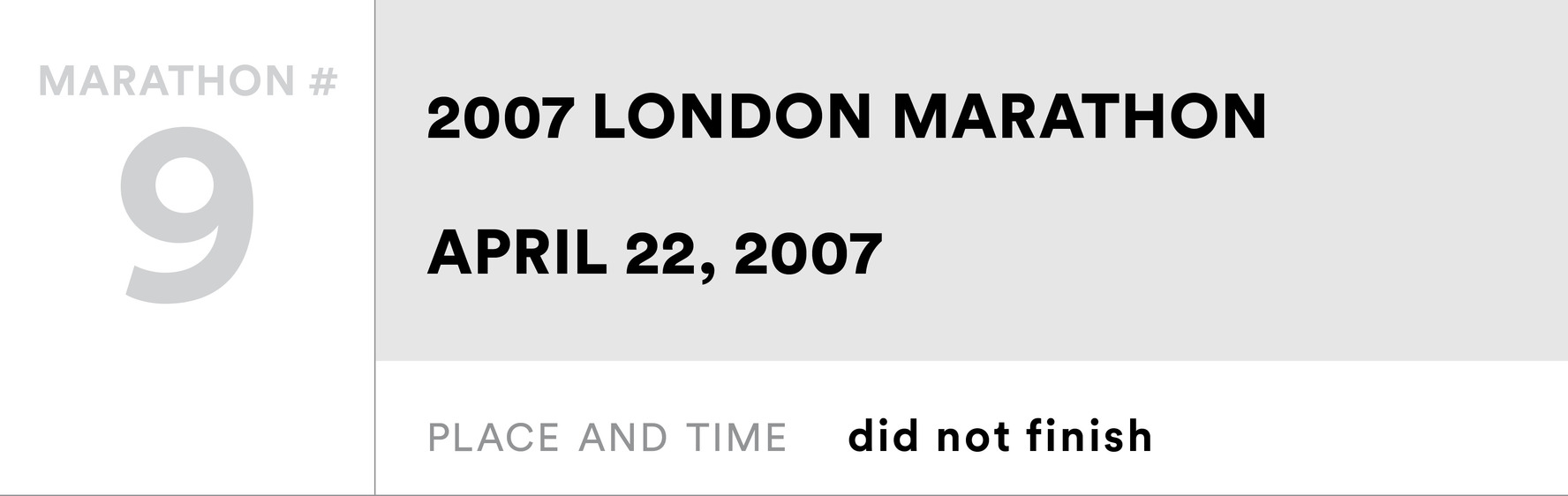

My run at the 2007 London Marathon—the only marathon I dropped out of—was an example of a great day setting up a bad day. I remain convinced, however, that not finishing that marathon was the right choice, and that my doing so turned out to be a good example of knowing when to call it a day.

A BLISTERING PACE

My main goal in 2007 was to make my third Olympic team at the Olympic Marathon Trials, which would be run in November on the day before the New York City Marathon. That race in hilly Central Park would be all about placing in the top three; time wouldn’t matter. I also wanted to improve my personal best in the marathon. The best time and place for that would be April in London, a flat, fast course where men’s and women’s world records have been set.

I started the year by placing third at the national half marathon championship. In that mid-January race in Houston, my Mammoth Track Club teammate Ryan Hall ran 59:43 to shatter the American record. Ryan would be making his marathon debut in London. I was elated for what he accomplished in Houston, but also was eager to see how we would match up when it really counted in London. Six weeks before the marathon, I defeated Ryan and other top Americans at the Gate River Run 15K in Jacksonville, Florida. I left Gate River satisfied with my sixth win there and the feeling that I was on the right track heading into London.

Unfortunately, I also left with a blister on the ball of my left foot. This wasn’t your run-of-the-mill running blister—it was the size of a golf ball. Two days after the race, back home in Mammoth Lakes, it became so painful I needed to go to the hospital to have it drained. My car wouldn’t start, so my teammate Deena Kastor, who had won the women’s race at Gate River, picked me up. She couldn’t believe it when the national 15K champion hauled himself out to her car using a broom as a crutch. When draining the blister didn’t really help, it was removed, resulting in a half-inch gash in the bottom of my foot.

This problem with my foot was more a wound than an injury. It remained an issue for the rest of my professional running career. With the exception of my final 26.2-miler, I reinjured the wound in every marathon I ran from 2007 onward. After a marathon, I could count on the area to be raw and require care and caution so that it didn’t get infected. If you ever saw me limping in the days after a marathon, it was almost certainly because the race had aggravated the wound.

The wound was even more troublesome right after I suffered it. Running was out of the question. So was simulating running in the pool, because the wound might get infected. I could cycle without aggravating the wound if I wore a Dr. Scholl’s pad. I rode twice a day, for up to three hours at a time. There was do-or-die pressure to stay in good shape and get to the starting line healthy. I was able to resume running in late March, including some short tempo runs and a good long run. Going into London I felt like I was still ready to run fast. I’d done a decent job of maintaining the great fitness I’d built before Gate River.

A TOUGH DECISION

Everything was perfect in the early miles of the London Marathon. Ryan and I ran together, just off the lead pack. It was great for us two teammates to be there helping and encouraging each other in one of the world’s top marathons. It was rare during my career to run alongside an American in an international marathon; two other notable times were with Alan Culpepper in the 2004 Olympics and Josphat Boit at Boston in 2014. I went through halfway on pace to run right around 2:09:00, which would be a personal best by almost a minute.

Then things went awry. I’d been running under 5:00 per mile, but suddenly my 14th mile was a 5:21. My 15th was a 5:28. The leaders were getting pretty far away from me, and my goal of a PR was quickly slipping away.

More important, I was running these slower times despite feeling like I was working just as hard as when I was running much faster just a few miles earlier. When that happens so early in a marathon, it usually means something is off mechanically—because you’re not running as efficiently, the same effort level results in running slower. In this case, my right Achilles tendon was becoming increasingly bothersome. I was compensating for the still-tender wound in my left foot by shifting more of the work to my right leg.

I could have kept running with that level of pain. But a serious Achilles tendon injury can be career-ending, whether because of running on it so long that it tears or doing enough damage to require surgery. I was especially mindful of those risks with the Olympic Trials and, I hoped, the Olympics coming up. I decided I couldn’t justify jeopardizing the rest of my career and, more immediately, the 2008 Olympics, just for the sake of finishing London with a really bad time. I stepped off the course in the 16th mile. (Ryan went on to place 7th in 2:08:24, the fastest marathon debut by an American.)

Dropping out of the London Marathon was one of the hardest on-the-go decisions I made during my career. Everything in my nature and my upbringing encourages enduring present difficulties to achieve more in the future. This was only the third DNF result in all my years of running, and my first in a marathon. Even more so than in shorter races, part of the marathon’s mythology is finishing what you start, no matter what. There were also professional consequences to consider: Would I ever be welcomed back at London after dropping out my first time there? A clause in my Nike contract meant that my base pay might be reduced. Despite all of those counterarguments, I was at peace with my decision to drop out, for reasons I’ll get to in a bit.

What I needed to get to immediately after dropping out was the finish line. My race number gave me free entry to the London Underground. I sat down in a train, with my head down, very much aware of the bib reading “MEB” pinned to the USA jersey I had on. My pity party didn’t last long. A recreational runner who had dropped out told me that Haile Gebrselassie, one of my heroes and one of the greatest runners in history, was on the train, having also dropped out. Then Stefano Baldini, the 2004 Olympic champion, got on, another DNF. When we got off the train near the race headquarters hotel, we saw American Khalid Khannouchi, a former London winner and world record holder, who had also dropped out. Most people figured we had finished, and some started congratulating us. (The short answer about how to handle that situation is to say “thank you” and keep moving forward.)

WHEN IT’S TIME TO CUT YOUR LOSSES

After London, I never dropped out of another race. Maybe it will help you to hear that I most definitely thought about dropping out of every marathon I ran, even when I won Boston in 2014. There’s a point in every marathon where you think, “Why am I doing this?!” As I’ll describe later, I was this close to dropping out of the 2012 Olympic Marathon, and nobody would have criticized me for dropping out of the 2013 New York City Marathon, when I suddenly couldn’t lift my leg with seven miles still to run.

We runners pride ourselves on our perseverance. We see things through despite pain and fatigue. Usually sticking it out is the right choice—those negative feelings are almost always temporary sensations along the road to meeting our goals. Getting past those bad patches makes our accomplishments that much sweeter.

But there are times when ending things early is the best choice. In running, if you have a big injury pop up out of nowhere, something is seriously wrong with your body. Continuing to run will make the injury worse and could cost you untold amounts of time off later. It could perhaps end your running career. The same is true of an ache or pain that causes you to limp or otherwise alter your running form. Continuing to run in that situation could not only worsen the original injury that changed how you run but also lead to injury elsewhere as you compensate for that initial injury. That was my situation in London—I was at risk of doing severe damage to my right Achilles tendon, which was strained because of how I was compensating for the wound on my left foot. Knowing when to cut your losses isn’t wimping out. It’s making the rational choice if you’ve properly calculated the costs and benefits.

That doesn’t mean it’s not difficult. When you’ve invested a lot of time, money, and/or effort into something, it can be hard to pull out of that endeavor even when doing so is the most rational choice. Economists call this the sunk-cost fallacy: You base your decision about the future in part on costs you’ve incurred and can’t get back. For example, you buy a movie ticket and are reluctant to leave before the movie is over, even though you hate the movie; exiting early feels like you’re wasting the money you spent on the ticket. In running, you might think, “I can’t drop out of this marathon, even though staying in it will probably result in long-term injury, because then all my training will be wasted.” In both cases, your “costs” (the price of the movie ticket, the many hours spent training) are past expenditures. If what you spent them on isn’t going to end well, continuing that undertaking stems from your emotional attachment to those costs, not logic.

Again, I’m not advocating quitting when things get tough. As I explained earlier in this book, “run to win” means running to get the best out of yourself. Usually that means overcoming short- and long-term challenges. But when things are clearly heading the wrong way, when continuing is obviously going to lead to long-term negative consequences, you need to have the wisdom to stop. That’s true in marathoning, that’s true in relationships, that’s true in business. Know when to cut your losses and move on to better things.

As I got older, I got better about applying this lesson to my training. For example, there were days when I planned to do an interval workout but just didn’t feel right while warming up, and I postponed the workout. I’ve also cut easy runs short based on how I felt. (Sure enough, sometimes the following day I came down with a cold.) Toward the end of my career I took more spontaneous days off from running, when I just wasn’t feeling well. I sensed that training that day would harm rather than increase my fitness a week later.

Obviously you have to know yourself well to be confident that you’re making the right decision in these cases, where there’s not the dramatic evidence like an injury that’s throwing off your running form. You don’t want to get in the habit of quitting or putting things off just because you don’t feel like doing the task at hand. Most runners, however, are strong-willed, and more often do what they planned to do regardless of how things are going. If you’re honest with yourself, you know when your body and mind aren’t on the same page. That’s when it’s time to save it for another day.

After London, the first order of business was to let my foot and Achilles tendon heal. They did so pretty quickly, and I had a great summer of racing on the roads and track. That was more evidence that I’d made the right choice to drop out of London. My fitness and confidence were high heading into the Olympic Marathon Trials that November. I had good reason to think I could get my first marathon win. I had no reason to think I was about to be tested as never before.