KEY LESSON

It’s better to be 90 percent ready and make it to the start line than to panic and become either overtrained or unable to start the race.

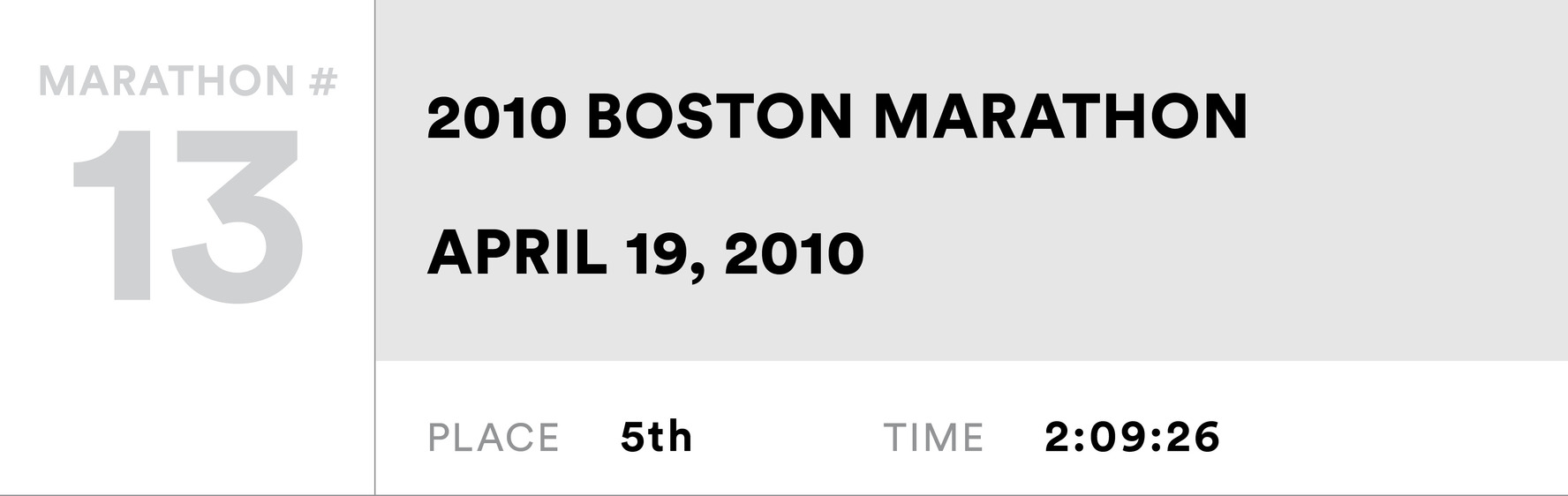

Spoiler alert: I didn’t follow up my win in New York City with the Boston Marathon title. Well, at least not immediately. I was hampered by a knee problem during my buildup for the 2010 edition of Boston. Although the knee was fine by race day, I lost too much training time to be able to vie for the win.

After I finished fifth at Boston that year, some people said my New York win was a fluke. Others said I’d lost focus. Still others seemed surprised that I wasn’t upset about my result. None of that was the case. Sure, I wanted to win Boston. (Who doesn’t?) But afterward I had renewed faith that breaking the tape on Boylston Street was still a very real possibility for me.

FOCUS, FOCUS, FOCUS

The runner’s version of “Dance with the one who brought you” is “Stick to the routine that has brought you success.” In running as in other fields, you’ll see people accomplish something huge and then never again approach that level of achievement. In some cases, it’s because the trappings of success distract them. This phenomenon is common among runners from Kenya and Ethiopia who quickly go from living on next to nothing to winning what in their countries is a fortune. They then lose the discipline that contributed to their accomplishments.

In other cases, people stay just as committed but they change their approach. A musician or author wishing not to repeat herself might try an entirely new creative method. Athletes can also feel like they need to shake things up—they’ll start working with a new coach or revamp their training program on the theory that the body needs a new stimulus to move past its current capabilities.

That was never my thinking. I worked with Coach Larsen from college straight on through the end of my professional career. I relied on the same staples (long runs, tempo runs, and interval workouts) during my fifteen years as a competitive marathoner. As I noted earlier, a hallmark of my career was consistency. For several years I was among the handful of guys in any marathon with a real shot at winning. At my level, who won on a given day depended in part on who was the healthiest during his buildup, who had the right mind-set on race day, and who best realized and capitalized on opportunities during the race.

So after winning New York, I wasn’t tempted to shake things up. I will admit that the post-victory hoopla and broadening fame were new elements. Much of that occurred, however, while I was taking my usual break from real training in the weeks after the marathon. I knew it was important not to get off track. Loving the process of training, and simply loving running, always made it easy for me to put my head down and get back to work when the time came.

As always, a key part of that routine was training at altitude. Training at altitude has many advantages: increased red blood cell production, which improves your aerobic capacity; regular testing of your tenacity, as you live and run in thin air; and few distractions, because you’re usually secluded in a quiet location. Training at altitude also has its challenges.

WATCHING MY FITNESS SLIP AWAY

In the United States, training at altitude in the winter is going to mean snow. Mammoth Lakes is well situated in that you can get to significantly lower altitude, where there’s less snow, in about forty minutes. I considered that my commute. Even in good weather, I usually made that drive for key workouts. The Round Valley area of Bishop sits at about 4,100 feet. That’s high enough to still give some of the benefits but low enough to allow for faster workouts.

Most of the time, however, you’re living amid snow. Doing so was my undoing before Boston that year. One day in late January I was clearing snow off the car. There was ice underneath the snow in the driveway, and I slipped on it and landed hard on my left knee. A week later, I fell on the knee again, this time while leaving the gym at seven thirty p.m. and learning the hard way that the snow that had melted during daylight had refrozen. The knee hurt when I ran. Trying to train through the discomfort only aggravated it. Pretty soon I was dealing with the early stages of patellar tendinitis. Such injuries are among the most frustrating, because they’re not initially caused by training mistakes or being lax about strength training or something else you can analyze and take steps to avoid in the future. They just happen during everyday life, and your running winds up suffering mightily.

The 100-plus-mile weeks I’d been hitting quickly became a memory. I missed a lot of days of training. Some of the days when I did run were short, easy runs on the treadmill. (I wanted both reliable footing and the option to end a run as soon as possible if the knee started bothering me.) Despite my babying the knee, it wouldn’t improve. January ended with me not running its last four days. After starting February with another day off, I ran 35 minutes on the treadmill on February 2, then 40 minutes on February 3, and then…I took another day off.

By this point I’d been feeling increasingly sorry for myself. After that early-February day off, I wrote in my log, “Get your head in the game.” Boston was only two and a half months away. I needed to be doing something every day, even if it was as little as 20 minutes of treadmill running followed by 20 minutes of swimming.

This improved mind-set helped when things got even worse physically. I started the second week of February with a 7.5-mile run, my longest in a while. And I ended the week with a total of 7.5 miles—my knee still balked whenever I tried to get back toward the type of training I needed to be doing for Boston. I told myself that Boston might be out of the question, but I didn’t need to decide immediately. I’d been in this situation before. From that experience I knew the right approach was to be patient.

RUNNING, BUT RUNNING OUT OF TIME

That patience was rewarded. I resumed running the second week of February and got in 38 miles that week, followed by 68 miles the following week. Obviously my situation was still far from ideal. But I’m guessing you know the wonderful feeling of seeing progress after weeks of setbacks. It’s always such a relief to feel like you’ve weathered a test.

By late February my mind and body were finally back on the same page. I don’t know how, but when I resumed adding quality to my mileage I had great workouts immediately. One of my first hard efforts was an 8-mile tempo run in 38:47 (a little slower than 4:50 per mile). I was able to build on that with a 10-mile tempo run at almost the same pace, and then a 15-mile tempo run at just under 5:00 per mile. To put that tempo run in perspective, that’s the first 15 miles of a 2:10 marathon, at a moderately high altitude of 4,000 feet.

These tempo runs occurred within the larger context of increased weekly mileage (I peaked at 111 miles during that buildup) and good long runs (I was able to work up to a 23-miler and a 25-miler). By early April, when it was time to start tapering for the marathon, I had come a long way since the desperate days of two months earlier. The training I was able to put together gave me hope that although I probably wouldn’t be able to win Boston, I could still go there and really compete.

I’m going into all this detail to give as clear a picture as possible about what was going on with my body and in my mind. I lost a lot of time waiting for the knee to come around. I was able to get going again at good volume with good quality, but I ran out of time to be ready to win the world’s most prestigious marathon.

What to do in these situations is always going to be a judgment call. One thing you definitely shouldn’t do is force the issue: Don’t push too hard or rush things in an attempt to make up for lost time. Even my 100-plus-mile weeks after not running a month earlier were cautious, logical progressions from what I’d been doing. I increased my mileage as doing so felt good and didn’t cause the knee problem to return or new ones to arise. I used the same process for increasing the length of my tempo runs and long runs. I probably could have immediately gone back to a 15-mile tempo run or a 25-mile long run. But the extra benefit wouldn’t have been worth it for the increased risk. It’s always better to be undertrained than overtrained. That’s especially the case when you’re returning from time off and have the running version of a deadline looming on your calendar. Showing up on the start line at 90 percent fitness is far preferable to not being on the start line because you rushed things and got hurt or sick.

As a professional athlete, I faced these situations perhaps more often. When I was hurt before the 2004 Olympic Marathon Trials, regrouping for another marathon a couple months later wasn’t an option—the road to the Athens Olympics went only through the Trials course in Birmingham, Alabama. You might have more flexibility in your schedule and opt for a backup race. That’s definitely the way to go if running your original race is going to be really frustrating or if you’re still hurt the week of the race.

A lot of times, though, sticking with your original race and adjusting your goals for it is probably the right choice. Marathons and the expenses related to them aren’t cheap. Your and your family’s routine may have been altered for months as you trained. In life in general, it’s rare that things go perfectly, or even how we’d like them to. There’s something to be said for being the sort of person who adapts to and absorbs adversity, shows up as planned, and does the best that’s possible on the day.

BACK TO BOSTON

That was certainly my mind-set standing on the start line in Hopkinton. I was pretty sure a win wasn’t in the cards. But a good result was still possible, and it was important that I do everything I could to make that happen. Early on, the lead pack and my body were amazingly cooperative in helping me toward that good result. The overall pace was within my capabilities, nobody was throwing in crazy surges, and my legs felt fine. I was still with the leaders as we passed the 17-mile mark and made the famous right-hand turn at the Newton Fire Station.

Just after we made that turn I felt something in my left quad. I told myself the Newton hills, including Heartbreak Hill, were coming up, and that the leaders probably wouldn’t be hammering up them. “If I can keep in contact with them,” I thought, “then maybe by the time we’re through the hills my leg will feel better and I can chase people down over the final miles.”

My leg had other ideas. The pain in my quad kept increasing, and I couldn’t take advantage of the fast stretch of miles after cresting Heartbreak Hill. My mind was telling my body that now was the time to start rolling, but my body couldn’t execute. The leaders got more and more out of sight. I didn’t fall apart horribly or anything like that. I just couldn’t go faster when that was the thing to do. Miles 20 through 24 were all in the range of 5:05 to 5:10 per mile. Over the last two miles I slowed to a little over 5:20 per mile. The pace felt comfortable aerobically, but my quad more or less gave up on me.

I finished fifth in 2:09:26. I dug deeper those last few miles in Boston than I did when winning New York. Many people think that when you win it’s because you worked harder than ever. The truth is that when you’re “on,” races often feel easier.

Up ahead, Robert Kiprono Cheruiyot of Kenya was “on” and won in 2:05:52 to shatter the previous course record of 2:07:13, set by Robert Kipkoech Cheruiyot in 2006. (Kipkoech Cheruiyot is the runner who won Boston four times and who I’d beaten in New York the previous fall.)

I later learned I had ruptured my quad muscle. Obviously, I wish that hadn’t happened. Still, that year’s Boston was a key race in my career. It strengthened my belief that I could win Boston. Despite the ruptured quad, I had run 30 seconds faster on the Boston course than I had four years earlier, and only 11 seconds off the personal best I’d set in New York. Those last two miles in the 5:20s alone put an extra 40 seconds on what my time might otherwise have been. And I’d run that fast just two months after resuming training. All of that told me that I could run under 2:09 on the Boston course. Most years, that will get you the victory there. I just needed to get to the start line healthy.