KEY LESSON

You never know who you’re going to touch and what you’re going to learn about yourself when faced with adversity.

One of the great things about marathoning compared to other sports is that pros and everyday practitioners compete on the same course at the same time. What better way to symbolize that we marathoners all experience the same joys and challenges? I love the spirit of common humanity on marathon day.

Throughout my career I strove to emphasize the common bond among all runners, regardless of pace. In Chapter 14 I talked about how social media has allowed me to connect with so many fellow runners I otherwise would never meet. Doing so helps to break down the artificial barrier some people erect between elite and recreational runners. Connecting with others helps everyone realize that, whether you run a marathon in two or four or six hours, there will be tough days. Where we can learn from one another is in how we handle those tough days.

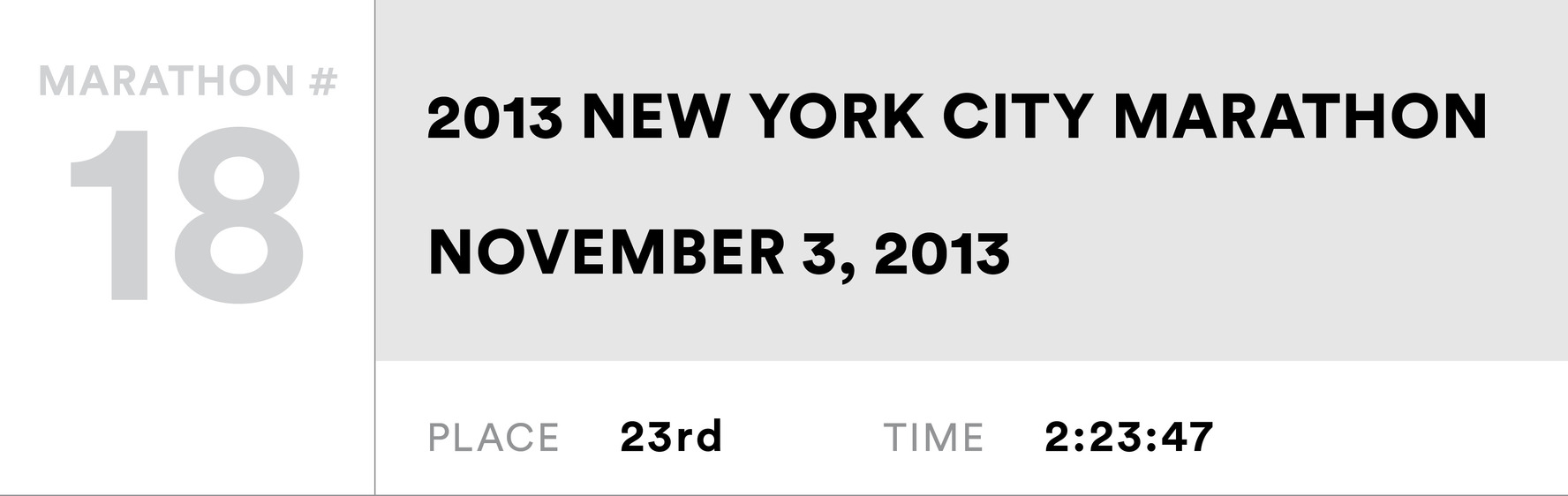

There was plenty to learn during and after the 2013 New York City Marathon, the slowest of my career.

RECLAIMING RUNNING

I was feeling a little beat up heading into that year’s marathon. I suffered a tear of the left soleus, one of the calf muscles, in September. I was coming back from that injury when, later that month, I fell hard onto an unfinished road, with gravel protruding from the surface, one mile into a planned 10-miler. My knee was gashed so deeply that I could see the white fat layer. It was bleeding profusely. I made a U-turn for home. The knee remained stiff and sometimes hard to bend for most of the rest of my buildup. The longest run I was able to get in was 20 miles, much shorter than the 25 miles or longer I prefer to peak at. I wasn’t sure if I could go the distance at race pace. At one point I discussed not starting with Coach Larsen as well as the race organizers, the New York Road Runners.

The thing is, marathoning was also feeling a little beat up. Hurricane Sandy had led to the cancellation of the previous year’s New York City Marathon. Then came the horrific bombings near the finish line of the 2013 Boston Marathon. The 2013 New York City Marathon would be a chance to reestablish running as a public celebration of the positive values of sport. It was really important to me to be part of that celebration. (I wasn’t alone in that feeling—50,266 people completed the race, the first time in history a marathon had more than 50,000 finishers.)

I knew my body was fragile. I knew I wasn’t in shape to contend for the win. But I decided I would put myself in the thick of it and see what happened.

ONE STEP AT A TIME

Race day was chilly and windy. There would be no rush of guys finishing under 2:10 as there had been two years earlier, the last time the race was run. There would, however, be stiff competition. Course record holder Geoffrey Mutai of Kenya was back, as was Tsegaye Kebede of Ethiopia, third in that record-breaking race of 2011. The reigning Olympic and world champion, Stephen Kiprotich of Uganda, was also on hand.

I was able to run with the leaders through about 16 miles, just before we entered Manhattan for the traditional increase in pace on First Avenue. I fell farther behind when the surging started. What usually happens is that the pace then settles back down for a few miles. I thought if I pushed hard I could regain contact with the lead pack and get pulled along at least until we reached Central Park. I dug down deep and tried to close the gap.

My give-it-a-go strategy got the best of me. Whereas at the 2004 Olympic Trials, I took a shot despite compromised preparation and finished wondering, “Where did that come from?,” this time it was like, “You knew you weren’t ready, and here’s the proof.” At the 19.2-mile mark, disaster struck. All of a sudden my right hip flexors stopped working. There was just no way I could take the next step. My mind said “go” and my body said “no.” I have felt the excitement of winning races; it can be such a beautiful thing that you don’t want to stop running. This experience was the complete opposite. I stopped. My mind and body had an awkward moment where they weren’t on the same page.

Although I had discussed not starting, I never seriously considered dropping out. I thought about all the people who would love to have the opportunity in front of me: those who had come from all over the world to run New York in 2012, only for the race to be canceled; those who were prevented from finishing Boston that spring because of the bombings; those who applied to but didn’t get entry into New York that year; those who love to run but for whatever reason aren’t able to do marathons. Also, my dad’s journey to escape Eritrea during the war with Ethiopia came to mind. He didn’t have aids like fluids and gels, whereas I could get fluids the rest of the way. That put things in perspective. I told myself, “I know what it’s like to win. Now I’m going to find out what it’s like to get to the finish line no matter what, even if I have to walk the last seven miles.”

My 20th mile took almost 10 minutes—twice the time of most of the previous miles, and not too far off my 5K PR of 13:11! When the hip flexor issue arose, I stopped for at least 30 seconds. Then I got going again, slowly, only to have to stop again. I had a vision of the elite runners’ sweep van coming to pick me up, and me needing to convince them I was going to finish. Even with wearing arm warmers, gloves, and a hat in addition to my singlet and shorts, I was already starting to get cold, now that I was running so much slower than my race pace. The warmth and blankets in the sweep van did cross my mind.

I probably stopped at least seven times. I don’t know for sure because I lost count after a while. I would stop and walk for the simple reason that my body couldn’t keep running. I would stop for 5 seconds, 10 seconds, whatever it took until I felt like I could get going again. I tried to stay positive, telling myself I was closer to the finish than I was the last time I’d stopped. I’d resume running at a shuffle and gradually get to a faster pace, but one still far from what I’d usually be hitting at that point in a marathon.

Mike Cassidy, a Staten Island resident, caught up to me with about 5K to go. Mike and I had just met that morning before the start. Our conversation then was brief. When I told Mike I’d see him out there on the course, he had replied I’d be way ahead of him. Usually, he would have been correct, given his personal best of 2:18.

But this was an unusual day, for both of us. As Mike pulled alongside me, he said, “Let’s go, Meb.” I said, “I’ll try,” just as I did when the other elite runners who passed during my frequent stops encouraged me to join them. I was able to match his pace. I was running on pure instinct now, knowing without ever having to consider it that someone by my side would make the last few miles much easier. I turned to Mike and said, “Let’s finish this together.” Mike agreed, even though he could have easily pulled away from me.

I’m pretty sure I didn’t stop once Mike and I started running together. On the most rolling part of the course, on the east side of Central Park, I would tell Mike when I’d be slowing, which was usually on the uphills. He would encourage me to focus on just getting to the top of the hill. The downhills weren’t as bad, because I didn’t need to lift my legs as much. I focused on leaning forward and letting gravity do some of the work.

As we reentered Central Park at Columbus Circle for the final 600 meters, Mike turned to me and said, “It’s an honor to run with you.” I replied, “Today is not about us. It’s about representing New York. It’s about representing Boston. It’s about representing the USA and doing something positive for our sport. We will finish this race holding hands.”

Which we did, our arms raised high. The official results show Mike finishing twenty-second in 2:23:46 and me placing twenty-third in 2:23:47. Figuratively, I can’t imagine that two runners ever finished a marathon closer than Mike and I did.

THE CAMARADERIE OF COMPETITION

After the race I was very emotional. I limped into the media center and repeatedly paused to cry while answering questions. Many people took this to mean I was upset about my result.

That wasn’t the case. As I mentioned in Chapter 7, I never had a race in my life that afterward I thought was worth a cry over disappointment. It was more what Mike said and realizing what our run together meant to him. I didn’t realize while it was happening that it would impact him the way it did. To me, Mike was a peer. We were just working hard together to get to the finish line. I was just a fellow runner.

That’s the beauty of our sport. Like I said, we had just met that morning, and only briefly, through Dr. Andy Rosen, a mutual friend who heads up the race’s medical team for invited runners. I didn’t really know anything about Mike—what his political views are, what his religion is, anything like that. I just knew him as Mike Cassidy the runner, a local guy good enough to start up front. He turned out to be a great guy who I’ve stayed in touch with and try to see and run with when I’m in New York. He eventually became a teammate with the New York Athletic Club and a contributor to my foundation. But at the time, it was all about two runners on a journey together, and I enjoyed it as much as he did.

Reflecting on those last few miles with Mike really drove home for me the deep bond that exists among runners. We all know it’s hard and that it hurts. If it were easy, everybody and their mother would do it. Those of us who have run a marathon have that special respect for the distance, and that mutual respect for anyone who reaches the finish line.

Even though I trained a lot on my own, especially for the last phase of my career, I always loved the company of my teammates, and even of my rivals. After 20 or 23 miles, if I’m running next to someone, of course I want to win—and so does he. But there’s no malice in those thoughts. We all want to help each other do the best we can.

You see the same in many sports, and many nonsport endeavors, where success requires endless hours of preparation and the rewards are mostly internal. At track and field meets, watch the field event athletes congratulate each other after the competition to see what I mean. There’s that mutual respect because you know what lies behind the other’s performance, regardless of how “good” or “bad” it is. Watching someone finish a marathon, you know from your own experience what it took to get there: all those mornings when you overcame the temptation to sleep in rather than run; all those long runs where you willed yourself to keep moving, and were glad afterward you did; all those times you headed out the door in search of the best you. We have far more important things in common than might be indicated by finishing a number of minutes or hours apart from each other.

My race in New York really drove home how you can inspire others on a day that wasn’t your best. In my next marathon I’d learn what could happen in that regard on your day of days.