KEY LESSON

Age is just a number if you learn to listen to your body and adapt to its changing needs.

Immediately after the 2015 New York City Marathon I turned my sights to making my fourth Olympic team. The Trials race in Los Angeles was run a little more than three months after New York. I knew from previous quick turnarounds what I needed to do—recover well, don’t rush things, just bring the fitness back.

Although it had been less than two years since I won Boston, some people didn’t think I was a top pick for one of the three Olympic spots. I was forty years old on race day and was one of the few top seeds in the race to have run a fall marathon. I reminded myself that age is just a number. So much of the marathon—and life—is a mental game. If you tell yourself, “Oh, I’m forty, my body aches more than it used to, I can’t do this, I can’t do that,” then those limitations you place on yourself can become self-defeating. You start trying not as hard, and then you don’t achieve what you’re really capable of.

When I say age is just a number, I don’t mean you can ignore it. Of course your body is going to change as you age. Starting in my midthirties I began to notice I didn’t have as much lean muscle mass as I had in my twenties. Recovery after long runs and hard workouts began to take longer. I struggled to hit the times in short, fast workouts, such as 400-meter repeats, that I had hit ten years earlier.

I was able to keep my career going at that point by listening to rather than fighting my body. I knew I needed to make some changes in my approach to account for the effects of aging. That’s not giving in, that’s being smart.

One big change I made was being more careful about my diet. I eliminated added sugar and moved away from meals that were overwhelmingly carbohydrate-based. I emphasized more lean protein with every meal to help with muscle recovery. I reduced the portions of most meals and, in contrast to my twenties, when I was a member in good standing of the Clean Plate Club, became familiar with the concept of leftovers. This diet helped me recover from hard training while being at a good weight on marathon race day.

Another big change I made was to switch my training from a seven-day cycle to a nine-day cycle. This change allowed me the extra recovery time I needed so that the runs that really matter—long runs, tempo runs, and interval workouts—made me fitter rather than wore me out. Instead of trying to cram in all my key workouts every week, I took two days of easy to moderate mileage after every long run, tempo run, or interval workout. I was still doing the work but spreading it out so that I could get to the start line healthy.

Finally, I made some mental adjustments to account for the physical changes. I’m a numbers guy who has records of all his training. If I want to, after doing a tempo run on a course I’ve run many, many times, I can compare that day’s result to what I ran a decade before. I learned that doing so is interesting but not helpful. What’s better is a constant dialogue with yourself: How did I feel? Did I put in a good effort without going all out? Are my goals still reasonable?

That mental adjustment is key to so much more than how fast you are in races. It gets back to not getting caught in the negative cycle I mentioned earlier of thinking, “I can’t do this thing or that thing as well as I used to, I’m getting old, I should leave ambition to the young.” So much of successful aging—in running and life—is acknowledging what has changed while not letting those changes define you. The way you go about achieving your goals will likely change, but the value of pursuing them doesn’t have to. Know yourself and keep coming back to this question: Are my goals still reasonable?

Going into the 2016 Trials, the answer to the last question was yes. I had enough experience to know that the training I was doing was good enough physical preparation. On race day, I knew I had a better storehouse of competitive experiences to draw on than anyone else in the field.

LIKING MY ODDS

As I thought about my race plan, I kept telling myself I’d won the world’s most prestigious marathon over a top field less than two years ago. And at the Trials, all I had to do to meet my goal was finish in the top three. Did I go in settling for third place? Absolutely not. When the gun went off I went for the win. But I thought that even on a day I don’t have my A game, I should be able to make the Olympic team. I’d done the work, and after twenty-two marathons I had enough experience to know what that training meant in terms of my readiness. Unlike a lot of the younger guys in the field, I wasn’t thinking, “Sure, I did the training, but how will I feel on race day?”

Over the years there have been enough surprises at the Olympic Marathon Trials that you don’t want to discount anybody. But realistically I figured there were five or six guys to watch in the race. (My good friend and longtime rival Abdi Abdirahman would have been one of them, but he had to withdraw before the race with an injury.) There were young up-and-comers like Tyler Pennel and Jared Ward, who had won the last two national marathon titles, and Luke Puskedra, who had the fastest American time in the marathon in 2015. There was fellow Olympic Marathon veteran Dathan Ritzenhein. And there was the wild card of Galen Rupp, the 2012 Olympic silver medalist at 10,000 meters, who was making his marathon debut at the Trials. I knew he would be tough and that he had a realistic shot at winning. But he was going to have to earn it if I had anything to say about it.

The temperature was in the 70s for most of the race, with a bright sun beating down on us on an exposed course. The heat was noticeable almost immediately. I figured that would mean a cautious early pace. I reminded myself what I wanted to accomplish—to earn one last chance to wear the USA jersey and to give my girls the memory of a lifetime.

With the race taking place in the city where I’d gone to college, the course was lined with old friends and fans. Skechers had made me a special uniform and shoes for the day featuring the yellow and blue of UCLA. Despite having lived in California since I came to the United States, this was my first marathon in the state. It felt like a graduation and homecoming combined.

I reminded myself to not get emotional early on. My plan: Be patient, let the field unwind itself, hammer the last 10K to separate the top three, and then go for the win. The main scenario I wanted to avoid was being in a pack of five or six with a mile to go against younger guys who might be able to outsprint me. I figured that if I followed this plan and had an average day, I could make the team. My mind was at peace.

MAKING THE TEAM

Fifteen of us went through halfway on 2:13 marathon pace. This was the conservative opening I had counted on. Watch for moves from the right people, I told myself, and be ready to make the move yourself if necessary.

It wasn’t necessary. After 15 miles, Tyler Pennel dramatically increased the pace. We had been running most miles at around 5:05 to 5:10. Tyler moved to the front and ran the 16th mile in 4:56, and then the 17th mile in 4:52. When Tyler passed the 17-mile mark, he had only two companions—Galen Rupp and me.

Tyler had been on a tear in shorter races in the months before the Trials, including a 3:58 mile on the track. He was one of the young, fast guys I didn’t want to have to contend with as part of a big group late in the race. So it worked out well that, with 9 miles to go, there were only three of us in the lead pack. I told Tyler, “We’re good, we’re good,” meaning that we’d accomplished the first big goal of getting the group down to three, the magic number for making the team. Usually in these situations the thing to do is to relax a little bit once the break is made, and then resume the real racing closer to the finish to determine first, second, and third places. I knew that Galen, in his first marathon and with his track background of sprinting at the end of races, would wait to set out on his own.

But Tyler wasn’t content to have broken almost all of the rest of the field. He was running for the win, from a long way out. He kept pushing—miles 18 and 19 were 4:52 and 4:56. Tyler was the one who made this race what it was, and I respect his courage, but I think he made a mistake in running like this. In the Trials, third is as good as first, because you’re going to be named an Olympian forever. At this point in the race, his goal should have been to clearly separate three of us from the rest of the field, not go for the kill. That was especially true against Galen and me, with both of us having Olympic silver medals and having set the American record for 10K.

Despite Tyler’s continued push, I didn’t panic. My experience told me it was unlikely that Tyler would keep running 2:07 marathon pace until the finish. Sure enough, in the 20th mile I sensed that he was starting to falter. I pushed to capitalize on his weakness. Galen went with me, and by the time we reached the 20-mile mark we had gapped Tyler by five seconds. Tyler eventually faded to fifth.

Things got a little weird once it was just Galen and me. Despite the wide-open roads we were on, Galen ran like you do on the track, staying as close as possible to your competitors. When I say as close as possible, in this case I mean it literally—he bumped into me a few times. Once is okay, especially if afterward you acknowledge your mistake, maybe offer a handshake or a “my bad.” But three times, with no acknowledgment? Then we have a problem. I said a few choice words and pointed to the ground to remind him we had the whole road to ourselves.

Galen pushed hard in the 23rd mile, running a 4:47 mile that I was unable to match. I reminded myself that “run to win” means different things in different contexts. Here, winning meant making my fourth Olympic team at age forty. Overextending myself to try to cover Galen’s surge could have jeopardized that main goal, because I might have hit the Wall in the last couple of miles and fallen to fourth place.

Although the outcome of any marathon isn’t sure until you cross the finish line, I was pretty psyched those last couple of miles in Los Angeles. I was running within myself and knew I was going to place second. Adding to the excitement was seeing a lot of familiar faces in the closing stretches: friends, former teammates and classmates, my parents, my brothers and sisters, and even my ninth-grade English teacher were on the sidelines cheering for me. Of course it’s a huge accomplishment to qualify for the Olympics. For it to happen in the city where my running really took off made the moment that much more special. I started celebrating over the last half mile, pumping my fist, pointing to people in the crowd, grabbing an American flag for the run to the finish.

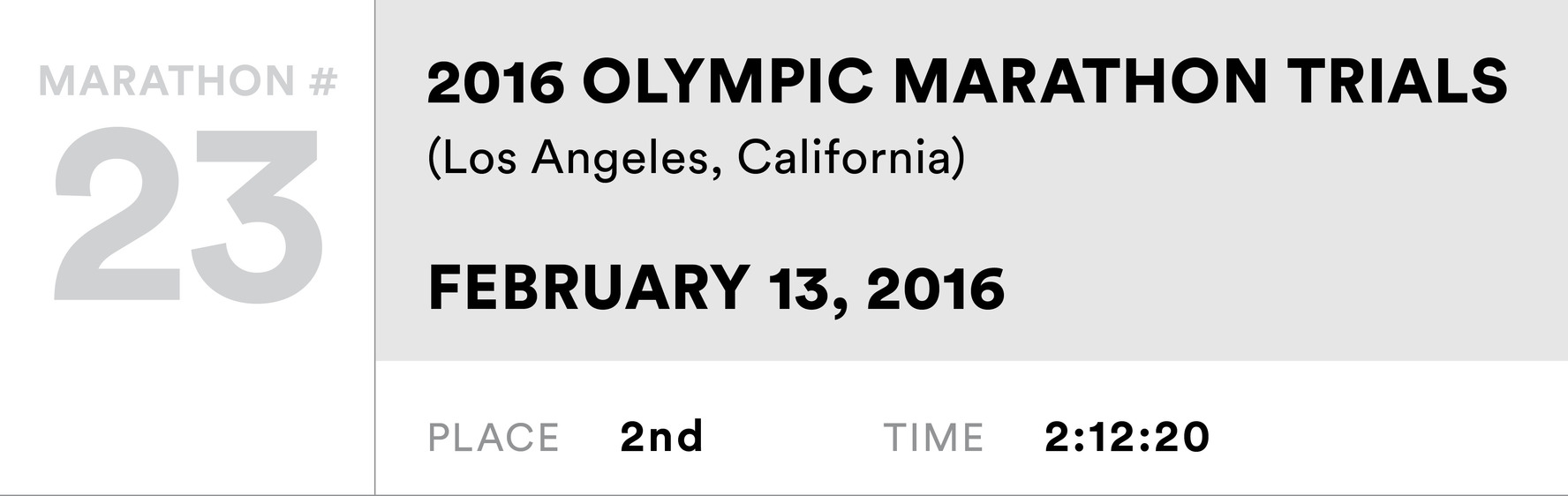

Galen won in 2:11:12. Jared Ward, already a master of pacing in only his fourth marathon, moved into third place in the 21st and finished in that position in 2:13:00 to complete our team. I was very satisfied knowing I’d beat all but one guy in the country, despite being more than a decade older than most of them. I had used my experience and collected wisdom in my preparation and on race day to get the best out of myself. And speaking of age, a bonus: My time of 2:12:20 broke my own U.S. masters marathon record.

Having Yordanos and our girls at the finish was a memory I’ll always cherish. I started thinking about our next family running trip, to Rio de Janeiro for the 2016 Olympics. On race day, I would be forty-one, the oldest U.S. Olympic marathoner in history. In the weeks after, I heard from a lot of people my age or older how inspired they were by my run. Some said they were now less likely to let their age limit them, and that they were rethinking how ambitious to be in running or work or other parts of life. I took these messages to heart as I started preparing for Rio. I was eager to show the world that age is just a number.