Preminger expected that acclaim for Laura would promote him to the Fox pantheon, but as he quickly discovered, his status remained that of a contract director whose professional fate was subject to the will of Darryl Zanuck. For his next assignment, instead of the kind of plum he was certainly justified in expecting, Zanuck accorded him a dubious honor. He would replace Ernst Lubitsch, who had recently suffered a heart attack, on A Royal Scandal, a remake of Lubitsch’s own 1924 silent Forbidden Paradise, starring Pola Negri as Catherine the Great. Otto was safely out of the B unit, it’s true, but he was being forced to step into a project where he would be following another director’s blueprint. Before his heart attack, Lubitsch had already cast the film (starring Tallulah Bankhead) and spent several months on preproduction.

The kind of team spirit that the assignment demanded of Preminger was part of the routine for a studio employee, and it was a lucky quirk of Otto’s paradoxical temperament that despite his independence he was able to bend to the “genius” of the system. It was never easy for Otto, a born bully, to follow orders, but he could force himself to be compliant if that is what he had to do to survive. In many ways, however, the administrative as well as artistic conservatism of studio filmmaking practice was congenial to him. The film factory’s need for punctuality, discipline, and financial prudence matched his personality to a T. And Otto was also temperamentally suited to the highly regularized approach of the so-called classical Hollywood style, defined by objective, centered compositions, “invisible” continuity editing, and unobtrusive camera work. For Preminger, having to remain within the parameters of the studio-imposed style was no hardship—he was not an artistic renegade determined to dismantle the system’s visual codes. Quite the opposite, having to conform to studio practice helped him to refine his own essentially mainstream sensibility.

As Willi Frischauer speculated, “In Zanuck’s eyes one foreign director was as good as another. Lubitsch, Preminger—what was the difference? Preminger, currently unemployed, was assigned.”1 According to Otto, however, Zanuck turned to him at Lubitsch’s instigation. The claim is credible. Preminger and Lubitsch were neighbors on Bel-Air Road, and along with Walter Reisch, the Berlin-born director William Wyler, producer Alexander Korda (then married to the actress Merle Oberon), and Max Reinhardt’s son

Marlene Dietrich on the set of Angel (1937) with the famously affable Ernst Lubitsch. In any contest with Lubitsch, whether judged on friendliness or artistry, Otto seemed destined to lose.

Gottfried, also a producer, they formed a close-knit group alert to job opportunities for one another. At his best in such social gatherings, Otto charmed his landsmen. “Otto was very generous,” Lubitsch’s daughter Nicola said. “I remember that he took my father and me downtown to see Rosalinda, the American version of Die Fledermaus. We were driven in a big limousine, and he took us to a big dinner beforehand. I thought he was avuncular.” (Nicola recalled Otto’s fellow Viennese Billy Wilder, a frequent guest at the Reisches’ Sunday afternoon get-togethers, as “not a nice man: vulgar. My mother didn’t want him for dinner. He had terrible table manners, unlike my father, who had no vulgarity whatsoever. My father was not the ill-spoken Jew that Herman Weinberg depicted in his book on my father. Otto had no vulgarity either. He and Reisch, who looked like a ferret and was very warm, were both wonderful hosts.”)2

This was not the first time that Preminger had been asked to step in for Lubitsch. Immediately following Lubitsch’s heart attack, Zanuck had asked Otto to work on a comic script Lubitsch had been preparing with Henry and Phoebe Ephron called All Out Arlene. From the results of that collaboration, however, Zanuck might have taken heed that Preminger was not a promising Lubitsch surrogate. The Ephrons found Otto “unbearable.” They complained that he spent too much time on the phone “quarreling with his cook over Saturday night’s menu or arguing with his tailor,” and unlike Lubitsch, Otto did not laugh at their jokes. “Where was that wonderful, free Lubitsch laugh that filled you with enthusiasm and made you try harder and be even funnier?” Phoebe Ephron asked.3 As displeased with the Ephrons as they were with him, Otto had the writers replaced. But the new, Preminger-supervised script of All Out Arlene was shelved.

To be sure, Preminger and Lubitsch had different styles personally and professionally. Where Lubitsch smiled and laughed, on the job and off, Preminger’s good humor tended to fade in working situations. “Although my father was terribly spoiled [like Preminger, Lubitsch came from a well-to-do family] and his own father was very choleric, he never raised his voice,” Nicola Lubitsch recalled. “He was moody, and he certainly didn’t like being challenged; once he didn’t speak to me for two weeks when I had questioned him. But he never screamed.”4 Lubitsch was renowned for his light touch— the ineffable grace notes he bestowed on his comedies of sexual peccadilloes that, in other hands, might have become coarse-grained. Preminger’s more literal, essentially realist style was decidedly heavier, tending to the ponderous. Preminger didn’t have Lubitsch’s whimsical point of view or his bemused slant on sexual misbehavior. Otto Preminger could not have made any of Lubitsch’s sparkling comedies of seduction and masquerade—and Ernst Lubitsch could not have made Laura.

The subject of A Royal Scandal— the Empress Catherine seduces a naive young officer who is protecting her from a palace revolt—was vintage Lubitsch. Of much less moment to Lubitsch than the political furor cooking in the wings was the Empress’s boudoir deportment; for Preminger, however, the political background was more enticing than l’amour and la ronde. Moreover, in a fundamental way Otto misunderstood Lubitsch’s approach to comedy. “The characters would do anything for a laugh,” he contended, “whether it was in keeping with what they represented or not… . the Empress of Russia behaved like no Empress of Russia ever would behave in order to produce laughs.”5 “Seldom has anybody missed the essence of the joke—any joke with such certitude,” Lubitsch’s biographer Scott Eyman commented.6 As he began directing the film Preminger felt “the era of ‘the Lubitsch touch’ was coming to an end. It was a change that Zanuck was not yet prepared to understand. Of course, Lubitsch was a first-rate filmmaker, but in his films the humor was based on situations and not on character. … A big change had slowly taken place. Audiences wanted more than the chance to laugh. They wanted to see characters on the screen who behaved consistently”7 As an analysis of either Lubitsch or a supposed change in film comedy, this is preposterous—and if this is how he really felt about Lubitsch’s work, Otto should not have taken the job.

“Lubitsch will rehearse the master scenes each day with Preminger and the actors and thereafter Preminger will take over as the sequence goes before the camera,” the New York Times reported on July 10, 1944. Clearly, Preminger would be working with his hands tied. He may well have wondered if this was his “reward” for Laura.

The inevitable clash between director and producer occurred in late July just before the first day of rehearsals. Flushed with excitement, Lubitsch announced that Garbo was interested in playing Catherine. Along with everyone else, Preminger had enormous admiration for Garbo, but he also was deeply indebted to the already cast Tallulah Bankhead, who had tried to help Otto get his family out of Nazi Austria. He made it clear that he would not “participate in anything that would hurt her” and assured Lubitsch that he would have to withdraw if Tallulah were replaced. “Lubitsch refused to listen to me. He insisted there would be some way to get around the situation. He took me to see Zanuck.”8 But Zanuck was not convinced that Garbo was a stronger box-office lure than Tallulah, who had just appeared in a major hit, Hitchcock’s Lifeboat, whereas Garbo’s last film, in 1941, had been a flop called Two-faced Woman.

Preminger, of course, won the first round—Garbo was never to make a comeback. But he felt that an aggrieved Lubitsch began to treat Tallulah

Otto (left) looks at Tallulah Bankhead, a good friend, on the set of A Royal Scandal.

with disdain. “He behaved rudely whenever he met her,” Otto claimed.9 Insulted, Tallulah threatened to quit, but Otto, who admired her bawdy humor, her liberal politics, and her talent, talked her out of it. He also had to deal with her terror of the camera. When the actress insisted that she could only be photographed from one side, Preminger and his cameraman Arthur Miller appeased her by placing a light on the camera (Miller called it “the Bankhead”) just above the lens that would compensate for Bankhead’s lopsided profile. A further bond between director and star was formed because of the hearty dislike they both developed for Anne Baxter, cast as a lady-in-waiting and the Empress’s romantic rival. A phony both on-screen and off, Baxter assumed a grand manner that rubbed them the wrong way. When Baxter asked if her grandfather, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, a conservative Republican and a noted anti-Semite, could visit the set, liberal Democrats Otto and Tallulah were incensed. With his star’s collusion, Otto devised a ruse. When Wright came to watch, Otto only pretended to shoot a scene between Bankhead and Baxter. He discovered “picayune problems” and stopped shooting ten times. Wright grew bored, as he was meant to, and left, as Otto flashed him a smile that had all the charm of a surgeons incision. Tallulah winked at her director. “I’ll never understand those stories about Otto, because he was awfully sweet to me,” she told the New York Times twenty years later, on December 6, 1964.

“Tallulah wasn’t right for the role,” recalled costar Vincent Price, by now a Preminger veteran. “If she had had Lubitsch directing, maybe she could have been. But not with Otto. It was difficult for all of us making the film because Otto really didn’t have a huge sense of humor, at least not in the way the material needed. Whereas Lubitsch had this particular humor the script needed. He could take three doors and make you roar with laughter just with people walking in and out of the doors.”10

Is it any surprise that the film was not well reviewed? “One for the jaybirds,” sniffed Otis L. Guernsey Jr. in the New York Herald Tribune on March 27, 1945. “Ernst Lubitsch, who produced, should blush,” Bosley Crowther grumbled in the March 27 New York Times. The box office was wan: $1.5 million against a cost of $1.7 million. For Tallulah, the tepid response spelled doom; for Otto, the lackluster film was merely an assignment he could, and did, shrug off with his customary sangfroid. “Someone said I was quite brave to accept the assignment,” he recalled. “I don’t worry about these things. I am not brave. It is part of my philosophy not to worry about what other people think of me. … I directed the film my way and if people felt that Lubitsch would have done it better, that is their opinion.”11

Lubitsch certainly would have done it better. For a boulevard comedy about sexual mischief Preminger’s approach was much too stodgy. And he seemed to have no ideas about how to give the talky script cinematic momentum. For example, after a scene in which courtiers have gabbed about the Empress, setting the stage for a shimmering entrance (perhaps Catherine might appear in deep focus, then walk forward through a series of doors), Preminger settles for introducing his star in a static long shot in which she is seated at her desk in the right corner of the frame. He allows Tallulah’s distinctive voice to carry the show, and she doesn’t betray his confidence. Her famed basso with its lascivious ripples and her distinctively clipped rhythm whip the piece into shape. Barking orders, casting sidelong glances at handsome young attendants and barbed looks at the dreaded Anne Baxter, Tallulah’s Catherine is a take-charge woman. As Lubitsch intended, Tallulah’s Empress understands that the art of seduction demands a royal performance. (Although she had many of the characteristics of Bette Davis, Bankhead lacked Davis’s brio as a movie star. Perhaps it was her too deep voice, her sexual ambiguity, her strangely ungiving eyes, the whiff of the stage that always hovered over her screen acting, which blocked her from attaining film star status. For all the rhetorical force of her performance, A Royal Scandal proved to be the end of the line for Tallulah as a film personality. There was to be only one other movie twenty years later, a cheap horror show called Die, Die, My Darling)

Zanuck was grateful to Preminger for having completed the project on schedule. The relationship between Otto and his employer seemed now to be fully healed. Otto ate with Zanuck frequently in the executive dining room.

A lady-in-waiting (Anne Baxter) is reprimanded by Catherine the Great (Tallulah Bankhead) in A Royal Scandal. Baxter’s high-flown manner irritated Tallulah and Otto.

He and Marion received invitations to the Santa Monica beach house. He had immediate access to Zanuck by phone and in his office. And the Zanucks were frequent guests at 333, where, as another frequent guest, composer David Raksin, recalled, “Zanuck appreciated Marion as a Viennese babe who gave great parties, and he also saw that she knew how to cope with Otto.”12

As a favor to his friend Gregory Ratoff, who was directing, Otto appeared in a cameo in a musical fantasy with a score by Kurt Weill and Ira Gershwin called Where Do We Go from Here? (1944). Playing a comically autocratic Hessian officer in an episode set in the Revolutionary War, once again Otto was being a good citizen. But where was the payoff? When would he get the compensation due him as the director of Laura? “Freedom of choice was in rather short supply at Twentieth Century-Fox under Darryl Zanuck,” he grumbled. “I had to turn out a string of films following rules and obeying orders not unlike a foreman in a sausage factory”13

Preminger did not like to repeat himself, but as he became an increasingly sophisticated decoder of Hollywood rituals he recognized that repetition was one of the pillars of the system. If you had a big hit with a particular kind of film, you were obligated to return to the scene of the killing. And so Preminger presented the boss with a story conceived in the Laura mold, a psychological suspense film with the potent noir title of Fallen Angel. Zanuck gave him an enthusiastic go-ahead.

In Fallen Angel an archetypal noir drifter, a con man and a womanizer, ends up by chance in a small California town, where he romances a sultry waitress and a well-to-do spinster. When the waitress is killed, the drifter becomes the prime suspect. As in Laura, appearances are deceiving and sex is twisted. To adapt the source material, a novel by Marty Holland, Preminger hired Harry Kleiner, a student of his at Yale in 1939. “Not one of my pupils succeeded,” Otto recollected in 1945. “This irked me, so I looked up Harry Kleiner, one of my best pupils, when I was in New York last year for the opening of Laura. I read a play he was working on, liked it, and brought him to Hollywood to do the script. His work on Fallen Angel vindicated me as a teacher.”14 As always, Preminger worked closely with the writer, supervising every line, and by the time the script was finished and ready to go into production he had committed it to memory.

After approving the script Zanuck gave Otto the task of convincing Alice Faye, the studio’s top musical star of the late 1930s and early 1940s, to play the role of the spinster. Faye was a strong-willed young woman who had often stood up to Zanuck. At the moment Zanuck and Faye were feuding again, but the mogul was eager to bring Faye back to the studio—she hadn’t worked in over two years—because she had a large and loyal following. Zanuck was hoping that Faye’s appearance in a straight role, her first, would boost the film’s box-office appeal. “I knew Alice had turned down sixteen or seventeen stories, and I also didn’t think she’d want the part [of June, a repressed, organ-playing spinster],” Preminger said. “It was different from anything she had ever done. It wasn’t glamorous, or the part of a pretty girl, or a very young one. But I knew it was real and down to earth, more like Alice’s own personality than the other roles she had played.”15 To his surprise Faye said yes.

The obvious choice for the role of Stella, the doomed, come-hither waitress, was the studio’s resident sexpot, raven-haired Linda Darnell. For Eric, the brooding drifter, Preminger was certain that Dana Andrews, his sad-eyed leading man in Laura, would be ideal. Shooting started on May I and finished on June 26. Remarkably, Preminger exceeded the original budget of $1,055,136 by less than $20,000—a rare achievement. He enjoyed working with Faye, who may have been truculent with Zanuck but not with him. Otto regarded Andrews as “a director’s delight. He always knows his lines, arrives on time [the two essential criteria for survival on a Preminger set], and knows what he wants to do with a part.”16 The film’s composer David Raksin recalled Andrews as “a man’s man, a great guy really, and so easy to work with. At Fox he was one of Otto’s favorites.”17

If Faye and Andrews were Preminger-proof, Linda Darnell was not. Eager to prove that she could do more than decorate the set, Darnell worked at the studio coffee shop to prepare for her role. But off the set she had already begun what was to be a lifelong battle with alcohol. “She was so scared she was almost always drunk,” recalled Celeste Holm, who was under contract to the studio at the same time.18 In either preventing or defending herself against an Otto tirade, Darnell proved to be helpless. “My impression was that Linda was learning her profession as she went along,” David Raksin noted. “I realized she was there not because she was a schooled actress—she was not—but because she was beautiful. That meant there would be a more or less sophisticated competition for her in the studio, which apparently developed. Little girls like that were sort of fair game. She tried very hard, but she couldn’t give Otto what he wanted on the first take, and he got very impatient. She would tremble, then he would scream.”19

Raksin wrote a song, “Slowly” (with lyrics by Kermit Goell), to be sung by Alice Faye.

Otto liked the song, but thought it wasn’t right for the character Alice was playing. Instead, he wanted to use my tune for the opening [in which the antihero rides into town on a bus], but I said it was wrong there too. “Don’t you like your own tune?” he asked me. “Of course I do, but it’s too sentimental for an opening where a guy on a bus is about to be thrown off because he has no money.” It would have made the picture start out in the wrong way. “It should open with a sense of urgency,” I told him. I said the song was right for Linda’s character. I was right, and he knew I was right. I respected him in turn: Otto was a smart son of a gun.20

Heard on the jukebox in the diner where Stella works, “Slowly” becomes the character’s theme song, its melancholy refrain carried by a wailing trombone whenever Stella appears.

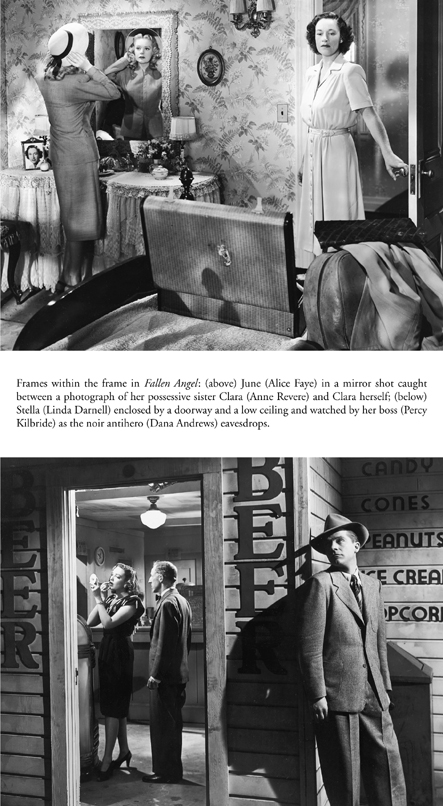

After his discomfort with the palace intrigue in A Royal Scandal, Preminger returns to form in Fallen Angel. His command of noir’s visual idiom is apparent in the arresting title sequence. Headlights from a bus pierce the infinite darkness of the open road as titles designed in the form of highway signs come into view. Throughout, the settings ripple with apprehension and instability, the imminence of mischance. The walls of the seaside diner where Stella works are crisscrossed with striped shadows cast by venetian blinds. Stella lives in an apartment at the top of a rickety staircase which, shot on the diagonal, becomes an augury of her dark fate. A rundown hotel room with a relentless blinking neon sign outside the windows reeks of the protagonist’s ill fortune. To underline his antihero’s entrapment, Preminger with his ace cinematographer Joseph La Shelle frames the character in low-angle ceiling shots in which space seems to be closing in on him.

As in Laura and many other noir thrillers, the narrative is riddled with suggestions of pathology. The spinster, June, plays the organ in a joyless-looking church, a crucible for sexual repression, and shares a house with her older, unmarried sister Clara (the frostbitten Anne Revere), who has an incestuous attachment to June that the film can only hint at. In June’s capitulation to Eric, an “homme fatale,” there is more than a hint of masochism. “Walk all over me,” she seems to say to the man who leaves her on their wedding night. A detective (played by Charles Bickford) who hangs out in the diner and has it bad for Stella is a sadist who administers a brutal beating (offscreen) to a man he pretends to suspect of having killed Stella. (In a last-act twist, the crazed-with-jealousy detective is identified as the murderer.)

Dana Andrews’s masked style strikes all the right notes for his ill-starred loner thrust into a noir whirlpool. Linda Darnell is equally fragrant as the small-town siren. When she makes her entrance at the café door, after having been missing for three days (shades of Laura), her allure is palpable. Fixing her stocking, and with a flower in her hair, she’s a fallen angel all right—a sweet girl with a tough veneer who seems forever destined to choose the wrong guy. Preminger failed only with Alice Faye, whose ineradicable common touch clashes with the well-born spinster she is playing. Her matte performance ended her starring career; many years later she was to appear again in small roles in which she is equally inexpressive.

For all its visual and stylistic victories, Fallen Angel did not match the achievement of Laura— an accusation Preminger was to face for the rest of his career. The problem, as it was often to be for the director, was narrative structure, getting the story right. “There are three stories in this one screenplay, but none of them is brought into sharp focus,” observed Otis Guernsey Jr. in the New York Herald Tribune on November 8, 1945. The finale, with the detective revealed as the murderer, feels like a last-minute rewrite. And the happy ending, with June reunited with Eric, also seems manufactured. It’s no wonder that Preminger could never remember how the film ended. “I was dressing for dinner one night and Fallen Angel was on television,” he recalled. “I watched it and I got quite involved; then we had to go out and I never saw the ending. I still cannot recall the ending.”21

Post-Laura, Preminger was becoming indoctrinated into the factory lineup. First he was a substitute for Lubitsch, a thankless task because he was being set up against a director with a far longer track record and vastly higher critical standing than his own. Then, with Fallen Angel, he slipped into the trap of trying to make a movie in the mold of his big hit. Neither project advanced his reputation in or out of the studio, and Preminger was in danger of becoming a company functionary marching in step with front-office orders.

His next project, a musical with an original score by Jerome Kern, at least offered the change of pace that Otto always relished. But the project held little intrinsic interest for him. “I took it because it was available; it was something Zanuck asked me to do, and at the time I was in no position to turn him down. And I didn’t want to: Zanuck ran the show, as I had learned.”22 “Today [1971] I would not be capable of spending three or four months on Centennial Summer— neither the story nor the characters would interest me. At that time it probably served some purpose in my life and in my career.”23 In fact, it is easy to see why the material “at that time” appealed to him. “Preminger’s thinking is strictly American,” a September 5, 1945, Fox press release announced. “He is Hollywood’s outstanding exception to the general rule that foreign-born directors prefer to make films with foreign settings.” The release then quoted Preminger: “For me, Europe is the past, America is the future. As Carl Sandburg once wrote, ‘The past is a bucket of ashes.’ Never having gone back to Europe I would hardly have a new viewpoint

about things European. But as a new American intensely interested in every facet of American life I might just possibly have something new to offer to stories with American settings.”

Centennial Summer, set in Philadelphia in the summer of 1876 and presenting an idealized view of an all-American working-class family, is one of those stories. Ordinary problems confront the Rogers clan. Mr. Rogers’s job on the railroad is imperiled. Two sisters become rivals for the same dream-boat. Family routine is interrupted by the sudden arrival of Mrs. Rogers’s elegant, gallivanting sister, who has had an amorous career among European royalty and who brings with her the handsome nephew of her late husband, a French duke. The homespun Rogers household is contrasted favorably with the representatives of European worldliness. Glazed with nostalgia for an American Arcadia, the slight narrative with its evocation of a vibrant young nation reflects the spirit of a country newly victorious in the world war.

Zanuck was itching to put the project on the studio slate because he was hoping to duplicate the success of the 1944 MGM musical Meet Me in St. Louis— for a while he even thought of calling his film See You in Philadelphia. Fox had already released one Americana musical, State Fair (1945), featuring an original score by Rodgers and Hammerstein; and rural dramas, perhaps a reflection of Zanuck’s own country-boy origins, had been a staple of the studio since its founding. His enlistment of Preminger for the project made sense on two counts. Zanuck was well aware of Otto’s patriotic fervor, and he knew he could count on the director completing the film quickly so that it could be released while the upbeat postwar mood was still ripe. Because of the elaborate production values, the film had a longer than usual shooting schedule (a full two months, from September 5 to November 9, 1945), but as Zanuck expected, Otto kept costs down. The final budget was a little over $2,200,000, as against an initial projection of two million dollars— almost any other director on the lot would have ended up spending far more of the studio’s money.

At first Otto welcomed the chance to work with Jerome Kern, the Broadway composer whose score (with Oscar Hammerstein) for Show Boat in 1927 had altered the course of the American musical theater. But Kern, volatile and impatient, was not an easy collaborator. And in a fundamental way their artistic temperaments were not compatible: Kern’s sentimentality collided with the aura of reserve that was an innate part of Preminger’s style. During production Kern was more ill-tempered than usual because he was working with a lyricist, Leo Robin, who was slow-moving. Kern was eager to return to New York to supervise the upcoming Broadway revival of Show

Boat, for which he and Oscar Hammerstein had written a new song, as well as to begin working with Hammerstein on a musical about Annie Oakley. Finally fed up with Robin, and refusing to wait any longer for him to finish the lyrics on a few numbers, Kern returned to New York in mid-October before the score had been completed. Before decamping he offered Preminger (appalled by Kern’s lack of professionalism) two songs he had written with other lyricists. (“All Through the Day,” with words by Oscar Hammerstein, and “Cinderella Sue,” with lyrics by E. Y. Harburg, are performed in the film as interpolated specialty numbers.) In early November Kern collapsed while walking in the theater district and on November 11, 1945, he died. Show Boat opened, as scheduled, on January 25, 1946; the Annie Oakley musical, Annie Get Your Gun, opened on Broadway on May 16,1946, with a score written with remarkable speed by Irving Berlin.

Zanuck opened Centennial Summer in July to tepid reviews and box office. Preminger got much of the blame. “Obviously the script was weak, but Preminger did little to snap it up,” Bosley Crowther observed in the New York Times on July 18, 1946. Ideally, the warm-hearted story and Kern’s robust, all-American songs need a cozy style not in Otto’s line. Centennial Summer doesn’t invite the audience in, as the equally fragile Meet Me in St. Louis does; and the rich sense of family and home that illuminates Vincente Minnelli’s direction of the MGM classic is missing.

Though Centennial Summer, Preminger’s first film in color (he was working with cinematographer Ernest Palmer), is hardly the equal of Meet Me in St. Louis, it is sturdier than its obscure reputation suggests. Preminger’s characteristic stateliness gilds the story with an appropriately ceremonial touch, and throughout, there are graceful set pieces—a smooth tracking shot around the outside of the Rogers house; craning, pirouetting camera movement in a ball scene. Preminger’s direction of the musical sequences is sensitive. Since the characters are not performers, he is careful to bind the songs to the story rather than to isolate them in a separate realm—music doesn’t interrupt the action but grows out of it, and to reduce the “taint” of performance Preminger often interrupts songs before they are over. Clustering around a piano, the family sings a ditty called “The Railroad Song,” which Preminger stages naturalistically as a spontaneous activity: this is something an American family of the period might do.

Only one song, “Cinderella Sue,” is entirely unmotivated—and it’s the best moment in the film, an inspired interruption. Into an Irish bar where two of the characters go for a drink, a black singer (Avon Long, who played Sportin’ Life in Porgy and Bess) and a group of black children enter suddenly and begin to sing the song. The camera moves in for a close-up as Long

Parade for the world premiere of Centennial Summer in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia. Preminger emerges from a cab at the premiere of Centennial Summer.

strums a banjo and one of the kids plays a harmonica; then during a dance break the camera retreats to a discreet distance. At the end of the number the kids pick up coins the white spectators toss at them, and then, as quickly as they entered, the performers exit. From a contemporary viewpoint the number—black performers performing “blackness” for the amusement of a white audience—certainly violates political correctness. But “Cinderella Sue” is showstopping in the best sense. To watch Avon Long’s strutting turn is to catch a glimpse of his Sportin’ Life. And in its irresistible melody and rhythm the number has echoes of the great Negro songs Kern composed for Show Boat. Anticipating his landmark all-black musicals of the 1950s, Carmen Jones and Porgy and Bess, Preminger films the interlude with evident respect and delight.

By now Preminger had become one of a small cadre of directors Zanuck knew he could trust absolutely. And Preminger, on his side, had developed great respect for DFZ. “I think he is basically one of the fairest men I have ever met,” he said. “He inspires a certain loyalty and following. He has a group of people, and I’m one of them, who would do anything for him. When we had an argument, there was nothing malicious about it. In spite of, or because of, everything, I have a warm feeling for him.”24 By 1946 Preminger also had one of the plushest contracts on the lot: $7,500 a week, a princely sum at the time.

As his position at Fox solidified, however, complications bedeviled Otto’s private life. He and Marion had been estranged for years, and in the sense that Marion had never quite received his full attention, the couple had been estranged from the beginning of their marriage. In Hollywood social circles their open marriage had long been an open secret. Otto was surprised, however, when in May 1946 Marion asked for a divorce. On a trip to Mexico she had met a fabulously wealthy (married) Swedish financier named Alex Wennergren who, as reported in an article in the Los Angeles Times on May 27, 1946, had been “blacklisted by the Allies during the war.” Agreeing to Marion’s petition for a speedy divorce, Otto consented to go to the Mexican consul in Los Angeles to sign papers. “Two days later I received a letter from Marion full of affectionate Hungarian farewells,” he recalled. “She would never forget our happy years together but she knew that I did not love her anymore and there was a man who loved her very much. She didn’t want anything from me except a few personal belongings that would be picked up in a few days by her fiancé’s private plane.”25 The plane never arrived, but Marion did. Mrs. Wennergren, apparently, was not willing to grant a divorce—more than that, she was madly jealous of her rival and began to stalk Marion. One afternoon in a post office in Mexico, Marion claimed that Mrs. Wennergren attempted to shoot her.

If Marion was a poor actress onstage, there was no question of her skill as the flamboyant leading lady of her own life. Whether or not the attempted shooting took place, or whether, as Otto speculated, it was “just a figment of Marion’s Hungarian imagination,”26 she lived her life with panache. A bit sheepishly but essentially unbowed, Marion returned to 333 Bel-Air Road in June 1946 to resume her appearances as Otto’s wife and to lunch regularly at all the industry favorites, including the Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel, Romanoff’s, Chasen’s, and the Brown Derby. Marion persevered, despite the fact that the charade of being Mrs. Otto Preminger had worn thin—Otto was enjoying his escapades as a freewheeling man-about-town and had begun dating Natalie Draper, a niece of Marion Davies and one of the extras on the Fox lot. Marion Preminger was on borrowed time and no doubt she knew it.

Long before Marion asked for a divorce, Otto often went on his own to parties at Zanuck’s Santa Monica beach house or for weekends in the desert at Ric-su-dar, Zanuck’s Palm Springs estate named for his three children, Richard, Susan, and Darrilyn. However, one weekend invitation, in June 1946, a few weeks after Marion’s request for a divorce, was a ruse. Zanuck, as always keeping daily watch on every production at the studio and aghast at the rushes on Forever Amber, based on Kathleen Winsor’s infernally popular novel, had decided to remove the director, John Stahl. To protect his investment—Zanuck had already spent over two million on the production, by far the most expensive undertaking in the studio’s history—Zanuck turned to the reliable Preminger to bail him out. When Otto arrived, solo, at Ric-su-dar on Friday afternoon, Zanuck informed him that he was to leave after breakfast the next morning, drive directly to the studio to view all the footage that Stahl had shot during the six weeks the film had been in production, and on Monday offer a candid assessment of what he saw. “Monday, you will tell me what you want to do,” Zanuck said.

“I’ll tell you now what I want to do,” Preminger shot back. “I want not to do Forever Amber. I read the book when it was sent round by the story department and I thought it was terrible.” He told Zanuck he was adapting Daisy Kenyon, another best seller aimed at a female audience, and did not want to interrupt the good progress he was making with his scriptwriter, David Hertz.

“You’re a member of the team,” Zanuck said sternly. “You must do it. I won’t blame you if it doesn’t turn out well.”27

Otto told Zanuck that if he agreed to work on “this trashy story” there would certainly be a reprise of the kind of argument they had had on Kidnapped and that Zanuck would end up firing him.

“You must help me,” the czar persisted. Then he assured Otto, who knew it to be a subterfuge, that as director he would be allowed to do whatever he wanted with the material.

“It was very difficult,” Preminger later recalled. “You wanted to get along with him when he talked like this.”28 In the end, as he had perhaps realized all along, Otto knew he had “no choice.”29 Daisy Kenyon, a heroine he believed in, would have to wait until he had rescued the lusty Amber, a heroine he despised.

Peggy Cummins (as Amber) and Peter Whitney in scrapped footage of Forever Amber, directed by John Stahl, replaced by Preminger. The actors were replaced by Linda Darnell and John Russell.

Preminger drove back to Los Angeles Saturday morning, looked over Stahl’s footage, and on Monday rendered his judgment. To proceed, he must have a completely new script, and the leading lady, Peggy Cummins, a young British blonde Zanuck had signed up and whom Preminger found “amateurish beyond belief,” would have to be replaced. Otto said he would need at least two months to prepare a script, and in the meantime production would have to be halted. In all his demands Preminger omitted a request for a producing credit—he was only too relieved that William Perlberg would have that burden. Zanuck agreed to the provisos, adding that as the script was being prepared they would “think about [Cummins’s] replacement.”30 Only later did Preminger discover that Zanuck had already hired Fox contract player Linda Darnell.

Demanding the right to choose his own writer, Otto turned to Ring Lardner Jr., who, uncredited, had written some of Waldo Lydecker’s dialogue in Laura. Although like everyone else Lardner thought the novel was “junk,” he accepted because he liked working with Preminger. “Otto was extremely bright and curious about almost everything,” he recalled. “He was also very good company, and when we worked together, we tended to spend as much time talking about the world in general as we did about the movie at hand.”31 Philip Dunne, who had written the first draft, was relieved, thinking he was now free of “the whole sorry mess. It was an amateur book that somehow caught on. It was a dollar catcher. It was supposed to be raunchy, and of course here were the censors looking at us: ‘Don’t you dare make a move.’ I wanted to make a spoof of it. But Zanuck said, ‘No. It’s a best seller. Let’s go with it.’ ”32 Curbing his desire to transform Winsor’s ribald story into a comedy, Dunne had turned in “a dreary, dutifully sanitized script.”33 Zanuck, however, wanted Dunne to remain on the project. As Lardner recalled, “I was now supposed to collaborate with Phil on a rewrite—a touchy situation, or rather, it would have been if he had been any less of an exemplar of graciousness and professionalism. As it was, the three of us, Otto, Phil, and I, established a strong bond based, in part, on a fervent common desire to be working on almost any property other than the one Zanuck had foisted on us.”34

Zanuck was risking a king’s ransom because he believed the novel’s popularity ensured a large audience. At 972 pages, Winsor’s chronicle of the fortunes of a poor country lass who sleeps her way into the court of Charles II in Restoration England is a monumental bodice ripper. Vixen, whore, royal consort, and sometime actress, Amber for all her erotic cunning fails to secure the affection of the one man she really loves, Bruce Carlton, a fortune hunter who in the end goes off to the new colony of Virginia with another woman by his side. Winsor draws on mountainous research to evoke a tapestry of the period: teeming with a Brueghelesque density of detail, her accounts of a historical plague and fire, of the decadent court of Charles II, and of the brothels and theaters where Amber works at various points in her career, provide bravura literary set pieces. Winsor, to be sure, is occasionally naughty, her passages about her heroine’s amorous exploits calculated to titillate her mostly female 1940s readers. But at the same time that she had her

Preminger, a photo of FDR, one of his heroes, on his office wall, with the script of Forever Amber, a film he was to direct under protest.

eye squarely on the box office, Winsor was also a real writer, and Preminger and his team should have been able to see that there was a terrific movie to be sculpted out of her saga.

Only after turning in his revised script did Preminger learn that Zanuck had already cast Linda Darnell. Otto had nothing against the actress (he never knew how much she had already grown to dislike him), and quite rightly thought she had done good work for him on Fallen Angel and Centennial Summer. But Winsor’s heroine was blonde and he couldn’t see the raven-haired Darnell in the role. He wanted a real blonde, Lana Turner, who was under contract to MGM. Zanuck protested. He was convinced that whoever played Amber would become a big star, and as he told Otto, he did not intend to give that kind of break to another studio’s “property.” Even after Zanuck decreed that Amber would be played by Linda Darnell, Otto, thinking he had an advantage—he had agreed to direct only as a favor to the boss—and confident of his rising place in the studio hierarchy, continued to promote Turner. He invited Zanuck and Turner to a lavish dinner at 333, and to prepare her for the meeting Otto coached Lana about how she should play up to the mogul. “She did her best,” he recalled. “She flirted shamelessly with Zanuck, at one point even sitting on his legs.”35 But Zanuck remained adamant, and Preminger, checking his audacity at this point, backed off, realizing he had no choice other than to proceed with an actress he could not envision in the role.

For her part, Linda Darnell stifled her anxiety about working with Preminger once again because she knew Amber was a star-making role. “I thought I was the luckiest girl in Hollywood,” she said at the time.36 Indeed, right after Zanuck announced that Darnell would play the coveted part she was given a major star buildup. Six weeks before filming was scheduled to resume in mid-October, Darnell was subjected to a routine as rigorous as that of an athlete in training for a championship event. She was placed on a severe diet. She began intensive daily studies with a vocal coach, British actress Constance Collier, in order to transform her Texas twang into a simulation of mid-Atlantic “movie speech.” In successive stages her brunette hair was dyed blond and twisted into a variety of shapes in preparation for the thirty-four different hairstyles Amber would have. She had to endure hundreds of costume fittings. And as a rising “star of tomorrow” she was required to give interviews in which, coached by the studio public relations department, she was expected to underline the similarities between her own humble background and Amber’s. None too flatteringly, in building a bad-girl image for Darnell, press releases reminded fans that Darnell was estranged from her husband, cameraman Peverall Marley and like many other Hollywood brunettes had had an affair with Howard Hughes. In forging a link between the actress and her role, the studio was suggesting that a slut had been chosen to play a slut. Insecure and not remotely divalike, Darnell submitted without a whisper of discontent to her preproduction regimen.

However, her costar Cornel Wilde, cast as the unattainable Bruce Carl-ton, wanted to bail. Wilde had already suffered through the aborted Peggy Cummins version, had rancorous memories of working with Preminger on Centennial Summer, and shared the writers’ conviction that the material was rubbish. But Wilde was a big star at the time, the kind of heartthrob the role demanded, and both Zanuck and Preminger wanted him to remain. When Wilde’s agents negotiated a sizable salary increase, the actor stayed on, grudgingly.

With no one except Linda Darnell excited about the project, Otto began filming on October 24. Darnell, whose days began at 4:30 a.m. with hair and costume fittings and often continued until eight at night, was under enormous pressure, and Preminger did nothing to bolster her confidence. Suffering her director’s almost daily explosions, Darnell, as she confided to her sister, became “convinced that Preminger was holding her back in the

Showing a bemused Cornel Wilde how to make love to Linda Darnell in Forever Amber. The actress feared and loathed Preminger’s autocratic methods.

part. Linda was not one to dislike many people … but Preminger she couldn’t tolerate. He was a good director, but a mean SOB. She hated him.”37 (During the filming of A Letter to Three Wives in 1949, when he needed a look of disgust from Darnell, director Joseph Mankiewicz placed as a prop a portrait of Preminger in a Nazi uniform.38) Exhausted, and demoralized by her director’s outbursts, Darnell midway through the seventeen-week ordeal collapsed and under doctor’s orders remained away from the set for ten days.

Other mishaps followed. To create a semblance of English fog that Otto wanted for an early-morning duel scene, a spray called Nujol was used. “It was a laxative,” Cornel Wilde recalled, “and half the cast and crew got diarrhea breathing and swallowing it.”39 The most harrowing incident occurred during the shooting of the Great Fire. After meticulous preparation—no traffic was allowed within a mile of the Fox lot—the sequence was shot at 3 a.m., with a battalion of fire trucks at the ready if something were to go wrong. Something did. The star was burned. “Linda Darnell just escaped death, because during the Great Fire a roof caved in,” recalled the film’s cinematographer Leon Shamroy. “I pulled the camera back and just got her off the set in time. She was terrified of fire, almost as though she had a premonition.”40 (Darnell was to die in a fire in 1965.)

The only member of the production who enjoyed working on the film was the composer, David Raksin, who hadn’t read the novel but felt the screenplay was

terrifically good for such a piece of trash. Phil Dunne and Ring were first-rate writers. As soon as I read their work I knew I wanted the score to have a symphonic sweep. I worked on it steadily for about six weeks. The picture has a helluva lot of music, and needs it. It has more themes than you would believe. I already knew a lot about the music of the period, but you can’t be too accurate to the period: it won’t work. Your aim is to simulate the music of the time. Otto didn’t touch a note of my score, because he recognized he had something extraordinary. Very few scores are like that. Zanuck sent down a note to Alfred Newman, who was to conduct, saying the score was magnificent in every respect.41

(Raksin earned an Academy Award nomination for his score.)

Filming dragged on until March 11, 1947. “It was the longest shooting schedule I ever had,” Preminger grumbled. “Zanuck was determined that this would be the biggest and most expensive and most successful film in history”42 After principal photography was completed, however, another round of problems ensued. Zanuck had bought the book because its scandalous reputation promised big box-office returns. Yet he and Preminger realized that the story of a promiscuous heroine who has a child out of wedlock and who seems, until she receives her comeuppance at the end, to be rewarded for her turpitude, would need to be toned down. As Preminger recalled, “We were very careful to stay well within the rules of the industry’s own censoring body,” known as the Hays Office, named for Will Hays, a former U.S. postmaster who was the first head of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association.43

The Hays Office did indeed pass the film, but the more austere (and at the time more powerful) Catholic Legion of Decency condemned it. In an effort to avert the financial disaster that a C rating from the Legion then represented, Spyros Skouras, the high-strung president of Twentieth Century-Fox, summoned Preminger and three priests from the Legion to a meeting in his New York office. Determined to protect the company’s $5 million investment, a near record at the time, Skouras proceeded to behave in a way that Otto would long remember. When the youngest priest, the chief spokesman for the Legion, began by chastising him for having dared to film Winsor’s banned book in the first place, Skouras with increasing agitation started twisting his yellow worry beads. After he saw that pleading with the irate priest to rescind the C rating had no effect, Skouras got down on his knees and began to cry, quietly at first but then with mounting fervor until his body was wracked with heaving sobs. At the high point of his aria, Skouras began to pound the floor furiously. Otto, no slouch in putting on a show to get what he wanted, was nonplussed. At that point the young priest, perhaps a little frightened by Skouras’s display, suggested that the Legion’s objection might be withdrawn if Fox changed the title. Skouras shrieked, as if in mortal pain: the title was the selling point of the film, and could not possibly be changed, he assured the priest in a voice shaking with indignation. Skouras promised the Catholic delegation, however, that the studio would make any changes they might request. “Just show [Mr. Preminger] what you want cut and he’ll cut it,” he announced.44 And proving once again that he could be a good citizen, Otto sat patiently with the priests in the Fox screening room in New York, listening to their concerns scene by scene. Perhaps because he had no faith in the project, he readily agreed to make strategic cuts in all the kissing scenes, and promised to schedule retakes to reduce the amount of the star’s cleavage in certain shots. After viewing Preminger’s sanitized version, with all the nips and tucks in place, the Legion bestowed its approval on the film. Preminger was to remember the “pathetic scene” in Skouras’s office a few years later, when he would have his own run-ins with the Legion of Decency and the Production Code Administration office. And with Skouras’s behavior as a negative model, he would refuse to capitulate.

On October 10, 1947, Forever Amber opened to big business, with Zanuck and Skouras making a quick and handsome profit on their expensive investment. The film even garnered some decent reviews. Bosley Crowther in the New York Times saluted Preminger’s “lush theatricalism” and noted that “although the film does not picture the details of Amber’s amours with such boldness as did Miss Winsor, it doesn’t spare the innuendoes, chum!”

In an interview with the New York Times ten years after the film’s release, Preminger recalled that Forever Amber was “by far the most expensive picture I ever made and it was also the worst.”45 He couldn’t have been more wrong. Closer to the mark was David Raksin’s assessment: “Otto sure did a hell of a good job with it.”46 Even more than Laura, the unfairly maligned Forever Amber confirms Preminger as a maestro of mise-en-scène. Working closely with Leon Shamroy (Preminger called him “a brilliant cameraman and a marvelous friend”),47 he assembled a procession of images that have the rhetorical power of master paintings. The Puritan dwelling where Amber was raised, shot with looming shadows and figures in silhouette lit ominously from below, is quickly established as a place of stultifying repression, the joyless rooms seeming almost to incite Amber’s amorous career. After examining herself in a mirror—Amber is always a self-conscious “performer”—she enters a packed, smoke-filled tavern where she waits on tables, mixing with a crowd of rollicking peasants in a mise-en-scène that oozes a primal vitality. Amber’s early career as a London cut-purse takes place in settings—dark, narrow lanes, dank rooms with threateningly low ceilings—roiling with underworld menace. Three scenes set in the theater where Amber is to become a successful actress are suffused with Preminger’s love of the stage. In the first, the heroine is mesmerized at

Preminger’s love of the stage is displayed in the theater scenes in Forever Amber. Amber (Linda Darnell), far right.

a performance of Romeo and Juliet. In the other scenes she is herself onstage, having become a leading player in the company of Sir Richard Killigrew. The richly detailed theater setting with its horseshoe-shaped auditorium filled with obstreperous patrons milling in the pit among women selling apples (and what else?) as the gentry primp and ogle each other in the boxes would surely satisfy the most exacting historian. A duel between Bruce Carlton and a jealous captain, shot in elegant horizontal compositions, takes place in a pearly, Corot-like early morning light. The decrepit house where Amber saves Bruce from the plague radiates an aura of disease and decay. Preminger and Shamroy shoot the scenes of the Great Fire in a chiaroscuro that has the virtuosity of a Georges de la Tour painting. And for the elaborate processions and dances at the worldly court of Charles II, they use a vibrant palette.

Preminger’s Old World formality is exactly what the material needs— Zanuck was astute in assigning him to be the rescue man—and not for a moment does Otto reveal his distaste for the story. Maintaining narrative momentum for over two hours and twenty minutes, his direction achieves genuine epic sweep. Shaping his star’s performance, however, he was less successful. Perhaps because he didn’t believe she could offer more, he presents Linda Darnell as an object to be looked at: a mannequin on display in period costumes and hairdos. As Amber she is no more than a virtual actress, a Restoration figurine with a small and inescapably contemporary-sounding voice. Under Preminger’s careful (perhaps too careful) direction, Darnell is never less than adequate. But the director gives her no chance to make a stab at the potentially bravura acting moments, as for instance when Amber saves Bruce from the plague, which a spirited, intuitive performer could have brought to roaring life. Preminger even subdues Darnell’s trademark sultriness. Her Amber is coquettish, but unlike Winsor’s heroine she is never allowed to be sexually threatening or to be consumed by lust.

Throughout the five-month shoot on Forever Amber Otto maintained a bruising schedule. Putting in ten-hour days on the troubled production, he also worked regularly with writers on scripts for two upcoming projects, Daisy Kenyon and The Dark Wood; read or at least scanned dozens of novels circulated by the Fox story department; and saw every film and play that opened in Los Angeles. He boasted that he took no vacations, claiming that once he completed a film he would “go to bed for three days” before launching into his next project. Because Amber, a film he did not want to make, took so long, Preminger hardly took his customary three days before plunging into preproduction on a film he very much wanted to make.