F. Hugh Herbert, the author of The Moon Is Blue, was Viennese by birth but had been raised in England. He and Preminger, neighbors in Bel-Air, had met when they were both under contract at Fox. The two became good friends who took frequent walks in the hills and canyons near their homes. In the summer of 1950, at the point when Preminger had extracted release time from Fox and was actively seeking film and theater properties, Herbert on one of their jaunts around Bel-Air mentioned a play he had just written about a would-be young actress, a virgin, who flirts with an all-American young bachelor and an older continental rake. No doubt reminded of the Viennese naughty-but-nice romantic comedies he had presented at the Theater in der Josefstadt whenever he had needed a quick box-office fix, Preminger was enticed.

Since 1926 Herbert had been writing frolicsome screenplays with such semi-risqué titles as The Demi-Bride, Adam and Evil, Tea for Three (all 1927), The Cardboard Lover (1928), He Knew Women (1930), The Secret Bride (1935), and As Good as Married(1937). But like Preminger, Herbert also had a keen interest in the theater. He made his Broadway debut in 1940 with Quiet Please, an unsavory comedy about a film star who teaches her straying husband a lesson about fidelity by having an affair with a gas station attendant. In 1943 Herbert had a commercial hit with Kiss and Tell. The queasy premise: in order to protect her secretly married brother a fifteen-year-old must pretend she is pregnant. “Although my father wrote material that had a ‘sexy’ touch, he was anything but a roué,” Diana Herbert remarked. “He was not a sophisticated man, but an innocent really, and he wrote about innocence. When he wrote about roustabouts, that was his dream of what he might have wanted to be. He and Otto shared an Old World sensibility. They were both formal and very proper. Otto was so austere that when we saw him my sister and I practically curtsied; we felt we had to.”1

When he put Herbert’s comedy into rehearsal in January 1951, Preminger had a lot at stake. He knew he couldn’t afford a second theatrical flop after Four Twelves Are 48, and since The Moon Is Blue was another slight piece about sexual mores, a bout of insecurity might have been understandable. But Otto had no such twinges, and throughout rehearsals, as his romance with Mary Gardner continued to thrive, he was in an upbeat mood. His major concern was a third act he felt needed reworking. He

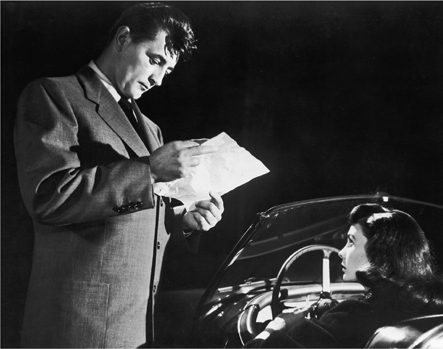

Two Old World fuddy-duddies, Preminger and F. Hugh Herbert, the author of The Moon Is Blue, confer with their Broadway leading lady, Barbara Bel Geddes.

wanted the author to “rewrite it no matter what the reviews said or how well the audiences liked it out of town.”2 Herbert agreed, but he may have been unnerved by the fact that the conversation took place as Otto lay in a large bathtub filled with soapsuds. “My father told me that he tried to keep a straight face, but it was hard for him because he was so proper,” Diana Herbert recalled. “He told me that Otto would often hold court in his tub, and it would always disconcert my father.”3

Act Three aside, Otto believed in the play and in a cast he felt was made to order for it. As the professional virgin Patty O’Neill he chose the winsome and appealing Barbara Bel Geddes. To play Don Gresham, the eligible bachelor who picks up Patty on the observation deck of the Empire State Building, he selected an expert light comedian, Barry Nelson. And as Gre-sham’s upstairs neighbor David Slater, a middle-aged sybarite with a prize-winning manner, he tapped Donald Cook, a veteran of drawing room comedy. “I was punctual, I knew my lines, I knew I could do the part, Otto knew I could do it, and there wasn’t a moment’s trouble,” Nelson recalled. “The play was a joy to work on, and Otto was a pleasure to work with.”4 When Biff McGuire replaced Barry Nelson, Preminger directed him in four intense days. “Otto was sometimes hard to decipher,” McGuire recalled.

But he knew what he wanted. “More champagne, less beer,” he would say—and that is what he got. His staging was very natural; he didn’t force anything. He directed us so that we got all the laughter that was involved, and I was surprised at how much there was. But sometimes I thought he was playing the role of the director rather than really being one. He did something that would embarrass the cast. He had an assistant, Max Slater, whom he had known in Vienna and whose real name was Schultz (Max changed his name to Slater, after the character named David Slater in the play). Max had a smile Otto enjoyed. He would call Max to the stage and say, “Smile, smile at Otto.” Max would come out, dutifully smile, then leave the stage.5

During rehearsals, Preminger, through numerous press releases, tried to create a naughty image for the show. “We have to get a bishop to condemn us,” Preminger said, according to Biff McGuire.

When The Moon Is Blue opened in Wilmington to a delighted reception, Preminger remained convinced that a rewritten third act was still mandatory. During the Boston tryout the cast performed the original third act each night, while during the day they rehearsed the new third act in bits and pieces as Herbert was reworking it. When the show opened at the Henry Miller on schedule on March 8, 1951, with a revised final act, it received a warm welcome. Detailing the play-by-play choreography for a tryst that never occurs—the dangling question throughout the evening is whether Patty will lose her virginity—Hugh Herbert’s slight comedy became Otto Preminger’s one major success in the American theater.

Taking advantage of his new contract with Fox, which allowed him to remain in New York for six months during the height of the theater season, Otto settled into an apartment in a converted mansion at 40 East Sixty-eighth Street. He saw virtually every show that opened on Broadway and he would often travel to see shows out of town. After the theater, often in the company of Mary Gardner and sometimes with Mary’s son Sandy along as well, he was a frequent patron at the Stork Club and El Morocco. Emboldened by the success of The Moon Is Blue, he announced that his next venture would be The Greatest Story Ever Told, featuring a cast of one hundred. “None of the actors will receive billing,” Preminger promised, “and because of the nature of the story they will not be identified with the parts they play Our plan is to take the show on the road for six months, and then into New York,” he told the New York Herald Tribune on February 12, 1951. He promised other productions: The Devil’s General, by Carl Zuckmayer; From Left Field, a play about baseball in a small town, a most unlikely choice for a man who had no interest whatever in either watching or participating in sports; and The Chameleon Complex, another light sexual rondelay in the Moon Is Blue vein. With producer Ben Marden, Preminger operated the Playhouse Theatre and booked its attractions. Over the summer as he scouted stock productions for possible tenants for the Playhouse, he was elated to have the job of casting and booking the second and third national companies of The Moon Is Blue and of directing Chicago and London productions as well. (The Moon Is Blue would run for 924 performances on Broadway and for a year in Chicago and London.)

When Otto had to return to Hollywood after six months, he managed to duck any commitments to Zanuck. He had already decided that a film of The Moon Is Blue would be his first independent production, for a company called Carlyle that he was setting up with Hugh Herbert. From a number of angles The Moon Is Blue was a shrewd choice. Since he was not planning to open up the play Otto could produce on a low budget. And he was counting on a censorship brouhaha to give the project notoriety. He did not want to rush into production, however, but would make the film only when the Broadway and touring companies had run their course.

After an abbreviated visit to Hollywood, Preminger returned eagerly to New York and to Mary, quickly adding two more plays to his portfolio of promises: another light comedy, The Brass Ring, and The Koenig Masterpiece, a drama by novelist Herman Wouk. Of all the shows during this period that Preminger had announced, Wouk’s was the only one that he staged. He began rehearsals at the Playhouse Theatre at 2 p.m. on December 4, 1951. That morning, he and Mary were wed in a brief civil ceremony, after which Otto dashed to the theater with his bride. Mary’s honeymoon was watching her new husband rehearse Wouk’s play (which had been given a new title, A Modern Primitive). “Otto was beaming and delighted, and Mary, blonde, very beautiful, and very charming, was in a bridal state of bliss,” recalled Paula Laurence, who had a principal role in the play “They both had an aura of radiant joy. Otto would take all of us out to extravagant lunches at which Mary was worshipful. Otto told stories and she laughed and applauded, as did the rest of us. At that moment they were clearly happy with each other. Otto was in a benign mood and remained so throughout rehearsals. Maybe he should have gotten married more often!”

As it turned out, Otto needed to be patient because Wouk’s promising play about a painter who embezzles money and flees to Mexico required major renovations. “Wouk was shy and serious,” as Paula Laurence remembered. “There was no friction between him and Otto at rehearsals, at least in front of us; I don’t think Otto would have allowed it. But I knew that Otto was asking for rewrites and Wouk was not doing them. Wouk had a good reason for resisting, however. He could say, in good faith, ‘I don’t want to rewrite because I haven’t yet seen what I have written.’ ” The problem was that the leading actor, Murvyn Vye, couldn’t remember his lines.

Otto was enormously patient with Murvyn, trying to get a performance out of this bewildered man [Laurence said]. He thought Murvyn would get the lines eventually and he would not fire him. Because he remained focused on Murvyn, however, the rest of us didn’t get much attention. At one rehearsal Otto turned to me and said, “Paula, you’re so charming in life and so boring in this scene.” All of us shrieked with laughter. I was playing a journalist who had come down to interview the artist, and I was boring because Murvyn would scramble the lines and I had no idea what he was talking about.

The show opened for a pre-Broadway run in Hartford, Connecticut, right after Christmas, and closed almost immediately. “We barely opened in Hartford, and some of us felt that we never really did open,” Laurence recalled. “Over the years I was to hear mean, scandalous things about Otto, fierce stories that were almost hard to believe. But I was a witness to the fact that there was a decent person there. And with that Viennese charm, which was like a show, a performance, though I wouldn’t say it wasn’t sincere on his part, and his well-known skill as a lover, he was certainly a ‘character’ and so regarded in the New York theater.”6

Diana Douglas, who played the artist’s mistress, had a different reaction to Preminger. Douglas felt that Vye was insecure because he knew he had been Preminger’s second choice for the role, tapped after Anthony Quinn had turned it down.

Knowing he was second choice didn’t help his confidence. Otto picked on him unmercifully during rehearsals, which only made him falter more. Otto would scream at poor Murvyn, the veins standing out on his forehead, literally foaming at the mouth. I had never seen such terrifying rage in anyone. He had Murvyn trembling and incoherent. It was sickening. I am sorry now that I was too chicken to challenge Otto directly over his cruelty toward a fellow human being, but I was craven and determined not to jeopardize my job.7

As Douglas reported, Vye “had what we found out later was a complete nervous breakdown. … he was carted away to spend the next four months in a sanitarium.”8 Before Preminger closed the show Saturday night, he asked if Diana would ask her husband, Kirk Douglas, to take over the role. The actress refused to honor the request.

Two weeks after closing A Modern Primitive, Otto received a call from his friend Billy Wilder asking him to play the commandant of a Nazi prisoner-of-war camp in Stalag 17. Preminger, newly married and still busy superintending The Moon Is Blue, said no, but Wilder insisted he read the script. After he did, Otto changed his mind. Wilder offered him $45,000 for three weeks’ work. Wilder and Preminger had much in common. Six months younger than Otto, Billy Wilder was born Jewish in Vienna and like Otto had enrolled as a law student at the University of Vienna. Unlike Otto, however, he quit after one year in order to pursue a career as a journalist. As a quite young man he moved to Berlin, where he continued to write for newspapers and where, as he was to admit, he also became a taxi dancer (in other words, a gigolo) at a hotel. In 1933 Wilder fled from Germany to Hollywood, where he arrived with none of the entrée or welcome that had been extended to Preminger. A crude, bitter man, over the years Wilder was to make as many enemies as Preminger, but despite a long downhill slide after 1960 his work was to be far more appreciated. In collaboration with Charles Brackett, Wilder wrote a series of highly regarded comedies, including Midnight (1939), Ninotchka (1939), and Ball of Fire (1941). In 1944 he cowrote and directed a canonical film noir, Double Indemnity. The next year he won Academy Awards for writing and directing The Lost Weekend, a portrait of an alcoholic. And with Brackett he won another Academy Award in 1950 for the screenplay for Sunset Boulevard, the best film ever made about Hollywood. Wilder had just received ecstatic reviews for Ace in the Hole (1951), a smug melodrama about a cynical journalist that failed commercially. Over the years the friendship between Wilder and Preminger was marked by fiery episodes—they weren’t on speaking terms for the last decade of Otto’s life—but when Wilder called Preminger in early 1952 to offer him a role, they were in a period of accord.

Wilder’s script for Stalag 17, cowritten with Edwin Blum, transformed a sentimental play about a German camp for Allied prisoners of war that Wilder had seen on Broadway in the spring of 1951. Wilder and Blum turned the material into a hard-boiled comedy about a group of prisoners who wrongly accuse the mercenary protagonist, a prisoner who operates a thriving black market business and runs bets on rat races, of being the camp informer. To enhance the biting tone he wanted, Wilder invented the character Otto plays, the witty, acidulous camp commandant. Happily married (Otto was living with Mary and his stepson Sandy in Anatol Litvak’s palatial pink house on the beach in Malibu), Otto reported to work in an ebullient mood and from the first day made it clear that he was there to take direction rather than to give it.

His well-being was shattered during the first week of shooting, however, when his beloved father died of cancer at seventy-five. Dr. Preminger had never spoken about the cancer that had caused him to waste away quickly and he had refused to submit to any surgery that might have prolonged his life. Otto was aggrieved. But his profound sense of loss was tempered by pride in the way his father had adjusted to life in America. Sixty-one when he had fled from Austria, Markus had felt that qualifying as a lawyer in an unfamiliar language was out of the question, so he decided, as Otto reported, “to invest the modest amount of money he had brought with him in the stock market.” After studying the American market and the financial histories of major corporations, Markus had proceeded to make sound investments. And as Otto boasted, Markus was “wealthier when he died than when he arrived here. In the meantime, he had lived well for over fourteen years, buying a house for himself and one for my brother as well.”9

(Although in 1942 Josefa had suffered a severe stroke that left her almost completely paralyzed, she survived her husband. “She was bedridden when I knew her, and needed round-the-clock care, and in those days she was not encouraged to seek rehabilitation,” Kathy Preminger remembered.10 Even as his own health declined rapidly in the six months before his death, Markus had maintained a vigilant watch over his wife. At the time, Ingo and Kate and their three children lived across the street from the elder Premingers, and ironically Kate, the young woman the snobbish Josefa had disdained in Vienna, became her greatest friend. “Kate behaved beautifully,” Otto testified.11 “My mother was so reliable and attentive that both my grandparents grew to love her,” Kathy said. “My mother told me that in her illness Josefa became sweeter.”12 When Ingo and his family moved into a larger house a year after Markus’s death, Josefa moved in with them. “She lived for several years in a room that later became our den,” Jim Preminger said. “I was very young, and she seemed very elderly to me, but she was still

Markus’s concern for his paralyzed wife Josefa, who suffered a stroke in 1942, is evident in this 1950 family photo.

a more formidable presence than my grandfather had been.”13 After Josefa began to require more attention than Ingo and Kate and their three children could provide, she was moved to a nursing home. Kate went to see her on a daily basis, bringing food and flowers. Josefa outlived her husband by five years.)

When Otto returned to filming after overseeing funeral arrangements for Markus, he was subdued but never for a moment other than completely professional. He admired Wilder’s methods. “Even though he came from Vienna, [Wilder] directed like a Prussian officer,” Preminger commented, as if talking about himself. “What he wanted with his words was rigid, absolutely rigid. Billy was a stickler for every word, because they were his words.”14 Surprisingly, however, Otto regularly messed up his lines. “When I hired him I told him every time he got his lines wrong, he owed me a jar of caviar,” Wilder recalled. “He may not have been the greatest actor, especially when it came to getting his lines right, but he was the world champion payer of debts. He missed a lot of lines, but he never missed sending a jar of caviar. He sent only the very best caviar. Now, that he did not have to do.”15 “I was happy to send [Billy] the caviar and the expense I didn’t mind, but the real price I paid was Billy directed me too well, and many people thought I was the part I played.”16

Preminger appears in three scenes. In the first, as underlings put down boards to protect his boots from contact with the muddy ground, the commandant makes a grand entrance as the American prisoners stand at attention. When the commandant speaks, his inflections laced with sarcasm and threat, he addresses the prisoners as if they were guests at a party of swells: “Guten Morgen, sergeants. Nasty weather we are having, eh? And I so much hoped we could give you a white Christmas, just like the ones you used to know. With Christmas coming on I have a special treat for you. I’ll have you all deloused for the holidays.”

In his second scene, entering the barracks to conduct a search, Preminger speaks again in a mock-gracious tone, as if holding court in a Noël Coward drawing room. “Curtains would do wonders for this barracks. You won’t get them.” His final scene has a visual gag Preminger appreciated. “The colonel wants to report to Berlin that an American officer suspected of espionage has been captured,” Otto recalled. “He has his orderly put on his boots for the phone call. During the call, he clicks his heels for his superiors. After the call, he has the orderly take off the boots. That’s a good joke, but I don’t know how many people got it.”17

Otto’s pungent performance in a hit film gave him the kind of fame few directors ever attain. But as he recognized and at least pretended to regret, it also provided ammunition to his growing list of enemies, who over the years would describe his acting in Stalag 17 as lifelike, or as an example of Otto on a good day. His work is certainly vivid, but it also reveals Preminger’s limitations. His eyes lack the liveliness of the natural screen performer, and, missing variety and shading, his vocal delivery slides toward monotony. Popping the character into the film for what are, in effect, three cameo appearances, Wilder himself seemed to be aware that a little of Otto’s Nazi goes a long way.

After completing his scenes in Stalag 17, Preminger had to report to Fox, where he was still contractually obligated to deliver a film a year. Dutifully he read scripts and stories, hoping to find a property he could take an interest in, but a few months passed without his finding a suitable vehicle. One afternoon, as he was reading a story synopsis, Zanuck called him to his office to inform him that Howard Hughes, the more-than-eccentric airplane billionaire who owned RKO, had requested Otto’s services. Zanuck told his startled employee that he had already accepted the assignment on Otto’s behalf: because Hughes needed a director who could work fast, Zanuck had recommended Otto. “[Zanuck] was indebted to Hughes for

Serving the master: Preminger as the commandant of a German camp for Allied prisoners of war in Billy Welder’s Stalag 17.

many favors financially and otherwise and wanted to show his gratitude by making him a friendly gift of me,” as Otto recalled.18

The assignment was a psychological thriller called Murder Story, starring Jean Simmons, under personal contract to Hughes. Since the British-born actress had arrived in America in 1949 to promote a film called The Blue Lagoon, Hughes had become a silent admirer. According to Hughes’s biographer Robert Brown, Simmons “awakened one morning in early 1951 to learn her contract with the British-based J. Arthur Rank Organization had been purchased by Hughes.”19 “Hughes bought me,” as Simmons herself recalled. “You can’t do that anymore, or you’d hear about it in the papers. He owned me, and I had to make four pictures for him.”20 The actress went to court to free herself from what she had come to regard as her indentured servitude to Hughes, and the upcoming film, for which she was contractually committed for no more than eighteen days of shooting, was to end her association with the billionaire. For the new film, because Hughes had already decreed that her hair was to be long, the enraged actress “whacked off the front of [her] hair with scissors. It had to be cut very, very short, which is absolutely what Hughes didn’t want.”21 In order to satisfy Hughes’s infatuation with long hair, Simmons throughout the filming would have to wear wigs.

Aware that he would be dealing with a disgruntled actress and leery of having to take orders from Hughes, Preminger was reluctant to proceed. After he read the script, he informed Zanuck that he refused to accept the assignment. That night in the witching hours Otto received a call from Hughes demanding a conference that, he was told, was to be held in a half-hour in Hughes’s battered Chevrolet. Promising Otto complete control of the project and assuring him that if he didn’t like the script he could have it rewritten by writers of his own choosing, Hughes pleaded with the director to take the job. “I’m going to get even with that little bitch, and you must help me,” he cajoled Preminger, who by the end of the postmidnight ride agreed—or was forced into agreeing—to direct.22

Preminger hired Oscar Millard, one of Ingo’s clients, to help him rewrite Murder Story. “My brother tells me you are a genius: let me see proof!” Otto exclaimed to his new writer. “Relations with Otto steadily deteriorated,” Millard recalled.23 To assist Millard, Otto hired Frank Nugent, an experienced screenwriter with a number of John Ford films on his résumé. Working quickly, with Otto providing daily supervision, they prepared a heavily revised version of Murder Story now entitled Angel Face. The original script may well have been a collection of genre clichés—the familiar story is about a femme fatale who ensnares a vulnerable man into a

Circe nailing her prey: Diane (Jean Simmons) gives Frank (Robert Mitchum) a look that promises trouble ahead in Angel Face.

web of passion and murder—but, reworked as Angel Face, it is Preminger’s most deliriously perverse excursion into noir.

The Tremayne family, enclosed in a hilltop mansion in Beverly Hills, is pure Hollywood Gothic. Charles, the paterfamilias, is a writer who has been unable to write since his late-in-life marriage to Catherine, wealthy, quivering with resentment and repression, and emasculating. The two characters are so wedded to their neuroses that they fail to register the lethal intentions of Tremayne’s daughter Diane, incestuously attached to her father and itching to get her hands on her stepmother’s fortune. To secure both the money and her father she is prepared to murder her stepmother. When Frank Jessup, an ambulance driver responding to an emergency call, enters the house radiating sex and indolence, Diane enlists him as a conspirator. With Franks help Diane rigs the family car so that it shifts into reverse when the driver intends to go forward. The plan misfires when Diane’s father by chance enters the car with her stepmother and both are killed. (It was Preminger, a very bad driver, who suggested the death-car motif.) Charged with murder, Diane hires a lawyer who concocts a scheme to exonerate her: if she marries Frank, they cannot testify against each other in court. After she’s released from jail Diane tries to confess to the lawyer but he silences her, assuring her that she can shout her guilt from the rooftops but she is protected by the law and cannot be tried again for a crime of which she has been acquitted. At the end, with Frank beside her, Diane plunges the car off the steep cliff next to the Tremayne house.

In this glacial salon noir, none of the principal characters survives, and family love, romantic love, justice, and the law are poisoned beyond redemption. Otto and his writers conjured a fallen world in which even the Tremayne servants, who snap at each other in Japanese (the wife is aggressively ungeishalike), and Franks normal-seeming fiancée, who turns out to be a tough cookie, provide no comfort.

Otto, for good reason pleased with the script, began filming at record speed on June 16, driving to work down Sunset Boulevard from his house in Malibu to the Lewis estate in Beverly Hills, which RKO rented to serve as the Tremayne mansion. In his autobiography Preminger, without once

The conspirators on trial for murder in Angel Face. In the foreground, the defective car engine that caused the deaths of Diane’s father and stepmother.

referring to her by name, recollected that the lead actress “was most cooperative. I enjoyed working with her.”24 That is decidedly not how Jean Simmons remembered the shooting. “Ah, Mr. Preminger … I’m sorry you mentioned his name,” Simmons said. “He was … very unpleasant. Talented, yes, and socially charming; but I was told he always picked a patsy, and on this film I was the one. I only got through it because of my costar, Robert Mitchum.”25 In a scene in which Mitchum was to strike Simmons, Preminger made the actor “slap her for real” and insisted on a number of retakes before an enraged Mitchum turned to the director and smacked him. Preminger left the set screaming for Mitchum to be replaced. But as a hired hand he was not able to get his way and he had no choice but to return to work. “Well, do you think we can be friends?” he asked his mutinous actor. “Otto, we’re all here for you,” Mitchum responded.26 There were no other incidents, but Simmons remained wary. She felt that following the orders of Howard Hughes, Preminger was treating her in a needling, disrespectful way. (On her next film, The Actress, she was directed by George Cukor. “He was everything Preminger was not. He was so kind and helpful. We rehearsed for two weeks, then shot for three. When we started to shoot, we were prepared.”)27

Mona Freeman played Robert Mitchum’s strong-willed fiancée. She recalled:

I had only one scene with Jean, who was such a nice, cute gal, and there weren’t any problems that I could see. I wasn’t aware that Jean was unhappy or that she didn’t want to do the film. Otto was certainly nice to me. He was very open to discussion. If I had any concerns I went to him; I felt I could go to him. It was Otto’s set—Hughes was never there—but there was no discord at all whenever I was there. We shot the whole thing in about twenty minutes, and frankly, it didn’t seem important. I’ve heard that it now has a huge reputation, especially in France, but I can tell you that at the time we didn’t think what we were doing was masterful: just the opposite. Mitchum, who was very easygoing, certainly didn’t take it too seriously. And neither did I. I’ve never seen the film. I’m glad to hear I was unlikable, though; I always played such likable characters.28

Working with Harry Stradling, known as the fastest cinematographer in town, Otto shot the entire film in twenty-one working days. He finished editing and postproduction by the end of September, and on December 11, 1952, RKO released the film. For a story about psychopathic behavior in a wealthy family, Preminger was exactly the right director. By this point in his career he was a master delineator of sexual derangement and of the noir set piece—and Angel Face has a number of the most memorable in the canon.

Early on, in his first visit to the mansion on the hill, Frank is bewitched when he hears a piano being played. Drawn by the music, he walks into the living room where Diane, a Circe nabbing her prey is seated at the piano, her dark eyes emitting fire and ice. The film has a memorably bizarre marriage scene. With shadows forming crisscross patterns on the wall behind her, Diane, a bedridden inmate in a prison hospital, marries Frank as prisoners who look like they have dropped in from The Snake Pit joylessly serenade the newlyweds.

Near the end, her parents dead and her husband about to forsake her, Diane takes one last walk through the deserted mansion, its shadowed rooms and corridors moaning with absence as Dimitri Tiomkin’s score—all wailing strings—mirrors the character’s unfulfillable desire. Here, in this climactic passage of operatic noir, and in contrast to his usual restraint, Preminger brings the film’s festering atmosphere to full boil. At the end of her walk Diane enters Frank’s room, sits in his oversized chair, and wraps herself in his big hound’s-tooth jacket, a moment that comes as close to a love scene as the film offers. After Frank in the finale tells Diane that he’s leaving for good, she asks to drive him to the train station. Frank, careless as ever, once again submits to her. In a moment that epitomizes the film’s fleeting gallows humor, Diane produces a bottle of champagne; seated in the car that is about to become an engine of death, the two former lovers toast each other. Then, shooting one last dark glance at Frank, Diane steps on the gas. Preminger and his scenarists offer a final turn of the screw. Before he had accepted Diane’s invitation, Frank had called a taxi, which arrives a few moments after Diane has driven the car off the cliff. His engine idling in front of the now vacant mansion, the taxi driver waits, as the film ends on “a moment of haunting emptiness like nothing else in the American cinema,” as Robert Mitchum’s biographer, Lee Server, commented.29

Jean Simmons may have thought he was brutal and Mitchum went after him, but under Preminger’s guidance the two performers were never better. Fueled by anger toward her “owner” and her “unpleasant” director, Simmons takes the bait. Her femme fatale, loaded with venom beneath a lacquered surface, is one of the most poisonous in noir, half-cocked and ready to shoot from her first scene at the piano. As the luckless antihero, the prey ensnared in the spider lady’s web, Mitchum oozes ambivalence. Neither Diane (nor the viewer) is ever quite certain about Frank’s motives. Is he attracted to, repelled by, or merely indifferent to Diane? Is he using her or allowing himself to be used by her? Is he on to her from the start, or is he so self-involved that he doesn’t really see what she is up to?

Unusual in withholding sympathy for any of its characters and marbled with astringent ironies, Preminger’s compact, fierce film is one of the masterpieces of the American cinéma maudit. American critics, by and large, were uncomfortable with the film’s seemingly un-American amorality its refusal to conform to sentimental notions about family or justice. In the New York Times on December 11, Bosley Crowther derided “the absurdly dismal finale” and warned “paying customers out for sense and sensibility to hang onto the brief appearances of Mona Freeman as the spunky realistic little nurse.” Otis Guernsey in the New York Herald Tribune bemoaned the film’s apparent detachment “from any real association with crime and punishment.” Parisian cinephiles, however, were quick to recognize Preminger’s achievement. Jean-Luc Godard placed Angel Face high on the list of his ten all-time favorite American films.

Racing through postproduction on Angel Face in the fall of 1952, Preminger began to prepare for the screen adaptation of The Moon Is Blue, his debut as an independent producer-director. While Hugh Herbert worked on the script, Otto began casting. On Broadway he had been delighted with Barbara Bel Geddes, the original Patty O’Neill, but he was concerned that on film she would not look young enough. Instead he chose Maggie McNamara, wonderfully fresh-looking at twenty-four, a former teenage model who had played the role in the Chicago company. To reassure his investors, Preminger needed to cast an A-list star to play the bachelor, Don Gresham. His first choice was William Holden, whom he had met while filming Stalag 17.

Offstage, Holden seemed like the man in the gray flannel suit, but as Otto sensed, the actor had a defiant streak. Holden, who accepted right away, relished the possibility of the censorship dustup he thought the film might provoke, and he also saw that starring in an independent film could be a possible financial bonanza. The contract that Carlyle Productions worked out with him—Holden would receive no salary up front but would take a percentage of the profits—established a financial model that was to become standard in the poststudio era.

Once Herbert’s screenplay was finished, Preminger submitted it to Joe Breen, who for nearly twenty years, as chief enforcer of the Motion Picture Production Code, had been the de facto guardian of screen morality. Breen did exactly what Otto expected and hoped he would: he rejected The Moon Is Blue. Twice. (Written and formally adopted by the Association of Motion Picture Producers [California] and the Motion Picture Association of America [New York] in March 1930, the Motion Picture Production Code had had no force until 1934, when Breen devised an economic sanction. Any film in violation of the Code and given a condemned rating—the dreaded “C”—by the Catholic Legion of Decency would be subject to a widespread Catholic boycott. Since its inception, as Breen had intended, the C rating had hovered like the sword of Damocles over filmmakers. In league with the fearsome Legion of Decency, Breen had thus been able to force the studios to comply with the Code.)

Preminger claimed that Breen’s objections focused on the use of such then taboo words as “virgin,” “seduce,” and “pregnant,” but in fact Breen’s disapproval was more far-reaching. He cited a provision in the Production Code that specifically interdicted seduction as “a subject for comedy” and assailed The Moon Is Blue for exuding “an unacceptably cavalier approach toward seduction and illicit sex.”30 Fearing Breen’s power, Paramount and then Warner Bros., Otto’s first two choices, turned down the project; it was only at that point that Otto approached Arthur Krim and Robert S. Benjamin, two young lawyers who had taken over United Artists in February 1951. In record time they had managed to convert the ailing studio’s red ink into black by attracting independent producers with promises of creative autonomy. United Artists had no studio of its own, but rented space from other studios. Krim and Benjamin quickly agreed to support Otto, pledging front money, distribution, and almost complete artistic freedom.

Krim and Benjamin, however, tried to talk Otto out of hiring David Niven to play the third principal role, David Slater, a potentially sleazy character who, in effect, pimps for his daughter while making a play for his downstairs neighbor’s virginal pickup. The lawyers thought Niven was out of fashion. But when he had seen Niven on Broadway in December 1951 as a debonair lover in a short-lived boudoir farce called Nina, Otto knew he had found the actor for Slater. Preminger went to bat for Niven with the same persistence he had shown in his campaign to cast Clifton Webb in Laura. “Otto is an immensely determined individual, and what Otto wants, he usually gets. He got me—bless him!” Niven recalled.31

The lawyers backed down, and Preminger thought he was ready to go when, late in 1952, the screenplay received yet another blistering rejection from the Production Code Administration office. Jack Vizzard, Breen’s associate, attacked the movie Preminger was planning to make as “unclean.” “The story was saying that ‘free love’ was something outside the scope of morality altogether, was a matter of moral indifference,” Vizzard protested. “What came into contention was the Code clause that stated, ‘Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationships are the accepted or common thing.’ Philosophically this was one of the most important provisions in the entire Code document.” According to Vizzard, what “made the hackles rise on the back of Joe Breen’s neck” was the way the script seemed to trump virtue in favor of sin. “To the devotees of sexual continence, the figure [Patty O’Neill] … is made to seem eccentric for being ‘clean,’ an oddball for clinging to her virtue in the midst of this ‘characteristically’ loose [and, by inference, preferable, more enjoyable] way of life.”32

In early January Preminger met with Vizzard and his colleague Geoffrey Shurlock for lunch at “21,” where Otto made it clear that he intended to shoot the script he had submitted to the Production Code Administration office. “As a token concession, [Preminger] offered to add dialogue at the end… condemning the ‘immoral philosophy of life’ expressed by Slater; beyond that, he would not budge,” as Leonard Leff and Jerold L. Simmons reported in their history of film censorship, The Dame in the Kimono.33 Dartmouth-educated and at that time Breen’s second in command, Geoffrey Shurlock was more modern than his boss. He had seen The Moon Is Blue onstage and thought it was “swell. A lot of fun.” He also believed that the Code prohibition against comic seduction was “idiotic.”34 Because of Shurlock’s conciliatory tone, by the end of the lunch Preminger modified— or at least pretended to—his defiant stance, and in principle even agreed to review Breen’s original list of objections as well as to submit the completed film to the Code office.

Preminger sensed that in Geoffrey Shurlock he had an ideological ally. Perhaps carelessly, Shurlock privately shared with Otto his dismay that just the week before Breen had approved the screenplay based on From Here to Eternity, James Jones’s “near-scandalous” novel. As a result Shurlock felt that Breen’s outrage over Preminger’s “harmless comedy of manners” seemed “not only irony but hypocrisy”35 Preminger may well have felt that, with a “mole” like Shurlock in the Production Code Administration office, Joe Breen’s tenure had a termination date. Nonetheless, he was resolved not to make any changes in the script in order to pacify Breen, and he fully expected that his film would not be given the Production Code Administration Seal of Approval.

Krim and Benjamin were not as fearless as Otto. They began to express concern that if the film did not receive the Code Seal, as it surely wouldn’t if Otto shot it as he was planning to, they would be unlikely to find any theaters in which to show it. They were reluctant to cancel their contract with Preminger, however, because to do so would seriously tarnish the image they had been working to build of United Artists as a place uniquely welcoming to independent producers. They hesitated, but by the end of January, allotting Preminger a modest $250,000 budget, they decided to go ahead: Otto could film his comedy exactly as he wanted. After deleting a clause from Preminger’s contract that “required delivery of a Code-approved” product, they negotiated a production loan from the Chemical Bank of New York and thereby, as Leff and Simmons reported, “committed UA to a frontal assault on Joseph L. Breen.”36

Otto moved quickly. He assembled his small cast and began three weeks of rehearsals. With his two male leads, Preminger was home free. David Niven had exactly the right touch. He tickled his lines as if delivering bons mots in a Noël Coward drawing room and raised his eyebrows at an expressive slant that suggested civilized wickedness. Not only was Niven tough enough to weather any Preminger assaults, in a way he even welcomed them. “Many actors don’t like working with Otto because he shouts even louder than Goldwyn [to whom Niven had been under contract] and can be very sarcastic. I love it. Actors have a certain amount of donkey blood in them and need a carrot dangled in front of them from time to time. The directors I dread are the ones who say, ‘You’ve played this sort of thing before—do anything you want.’ Otto dangles carrots.”37 William Holden was a little too solemn for the material and didn’t seem to be having as much fun as Niven. Nonetheless Holden had an intuitive sense of how little the camera needs—to Preminger’s delight, his star seemed incapable of overacting. Maggie McNamara, however, provoked a few Preminger tantrums. Although she had played the role in Chicago and then in New York (“I know she had trouble during the New York run,” Biff McGuire recalled),38 she was a jittery newcomer with a fragile ego (McNamara was to commit suicide in 1978). When, unlike her costars, she was unable to give him what he wanted on the first take, Otto would roar that her flubs were costing him time and money. McNamara brought out both the best and the worst aspects of the director’s temperament. As with all of his young discoveries in the future—the performers he would pluck from obscurity because he believed he could develop them into screen stars—Otto was alternately cranky and caring. After one of his flare-ups, which would pulverize his protégée, he would shower her with reassurance. He knew that McNamara, pert and appropriately dignified, indeed “virginal,” had the right qualities for the role, and like everyone in the company, he genuinely liked her. “Maggie was dear and sweet,” as Biff McGuire said, “but she wanted desperately to be an intellectual—to be someone other than who she was.”39

Preminger shot the film in twenty-one days, an impressive achievement considering the fact that he also filmed a German-language version on the same sets in the same time frame, getting two films for the price of one. For

With his insecure young discovery, Maggie McNamara, on the set of The Moon Is Blue.

the German version, called Die Jungfrau auf dem Dach (The Virgin on the Roof), Preminger cast Hardy Krüger and Johanna Matz, both with major careers in German theater and films. “When the American actors would leave the set, we would go in and do the same,” Matz recalled.

I had to do exactly like Maggie, which was hard, but she was very nice. It was very quick and very disciplined work. Not everybody likes this kind of work—it was unique. But I liked to do it. Otto was a little bit nervous—we worked so fast. He was sometimes a little bit loud, but Germans are loud anyway. I like to have “temperament,” and he had it! So what? It was very modern, very simple: he says what he wants and we do it. Only one thing was hard: in German you need more words than in English. So sometimes there were complications.40

By early April Preminger sent a completed film to the Production Code Administration office. He had made a few minor concessions to Breen, but he received exactly the response he wanted: Breen denied certification to The Moon Is Blue because of its “unacceptably light attitude toward seduction, illicit sex, chastity and virginity”41 Fully prepared, Preminger went into attack mode, writing a letter of defense in which he claimed that his film was highly moral. “Our picture … is a harmless story of a very virtuous girl, who works for her living, who neither smokes nor drinks, who is completely honest and outspoken, who resists temptation and whose one aim in life is to get married and have children… . There are no scenes of passion … no scenes of crime or vice.”42 Breen was immovable. As a last resort Preminger and United Artists decided to appeal his decision to the board of the Motion Picture Association in New York. The lawyer representing the Production Code Administration office argued that The Moon Is Blue would be “highly offensive to many parents to whom virginity of their daughters is still a matter of greatest concern, and who do not consider this a matter to be laughed at.”43 Headed by Nicholas Schenck, the president of Loew’s and the brother of Otto’s original American mentor, Joe Schenck, the Motion Picture Association upheld Breen’s condemnation. Nicholas Schenck maintained that he wouldn’t “let [his] daughter see it. It’s true that the girl is not seduced in the time she spends with the boy, but other girls in a similar situation might get closer to the flame.”44

For Preminger and United Artists, the moment of reckoning had arrived. Had they been bluffing all along? Had their defiance been an act of bravado that would now crumble? Would they—indeed, could they— release The Moon Is Blue without a Production Code Administration Seal of Approval? Many industry pundits predicted that no major theater chains would book the film. But working arm in arm with United Artists, Preminger persevered and in a short time secured a few key theaters in Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Francisco. In Los Angeles, Preminger was fortunate in booking the Four Star, a sedate house on Wilshire Boulevard in the then fashionable Miracle Mile district. The theater had a distinguished history and only recently had presented a lengthy, reserved-seat engagement of MGM’s Julius Caesar. An exclusive booking at this location would give Preminger’s film a touch of class.

When Otto saw the ad that the studio’s publicity department had designed—a half-nude young woman gazing up at the moon—he was apoplectic. “The ad suggested] that the movie after all was pornographic,” he maintained.45 In another decision that was to have historic reverberations, he hired a New York graphic designer, Saul Bass, to prepare a new ad. Preminger and Bass set to work under terrific time pressure. “We were like Samurai warriors, and always going up in smoke,” as Bass recalled.

Oh, the screaming, and we threw things. He really taught me how to fight. Otto, you see, liked to fight. It was half-serious and half ritual; he was tough, autocratic, he jealously guarded his prerogatives: he was the boss. But there was also such generosity of spirit, and he was so accessible—it was always so easy to get an appointment. He was the best client I ever had—and the most difficult. He brought out the best in me and at times I really wanted to throttle him. He was very critical, very difficult to satisfy, but what I discovered is that with all the conflict and the yelling the work was better at the end than at the beginning. And that was a powerful realization. Ours was a richly volatile relationship. Eventually, I learned to love the guy46

Although Bass judged his first important work with Preminger to be the ad he designed in 1955 for The Man with the Golden Arm, his whimsical design for The Moon Is Blue— a drawing of two pigeons perched on a win-dowsill—is also noteworthy. “Suggestive” in the mildest way—no one could possibly have read the design as “pornographic”—it evoked the film’s light tone. And in focusing on one image it represented an entirely new approach to film advertising. “Otto and I made a commitment to one central idea to promote a film, rather than the potpourri stew notion that was customary at the time, in which you threw everything into the advertisement on the theory that there will be something in it for everyone.”47

Long before it opened on June 3, 1953, The Moon Is Blue was a cause célèbre. For weeks prior to the premiere, Preminger held dozens of press conferences during which he defended his film’s morality while deriding Breen’s “hypocritical interpretation of an antiquated Code.” “Nobody’s character can possibly be corrupted by this harmless little comedy,” Otto asserted repeatedly. “Why did nobody object to the play when it ran in theatres across the country?”48 Indeed, the whole point of the piece is that nothing sexual happens. A young professional man picks up a perky young actress and takes her home, where they talk and flirt and make plans for a cozy dinner. When she meets her new beau’s dashing upstairs neighbor, the young woman flirts with him, chattering gaily about her virginity. In the end, after all the palaver about seduction, and with the young woman’s chastity undefiled, a once-in-a-blue-moon event occurs: a pickup blossoms into romance, and the bachelor and his date decide to get married.

Preminger opened the discussion to concerns that went far beyond his “little comedy.” He contended that his refusal to cut any “offending” words from the film was not because he believed the excisions would inflict irreparable damage but because he was opposed to censorship. “It is an evil institution, and if we give in to it on small matters this is the first step toward the kind of totalitarian government that destroyed my country, Austria,” he thundered with impressive conviction.49

“A middling and harmless little thing, speciously risqué,” opined Bosley Crowther in the New York Times on June 3, setting the terms in which the film was received. “The film is not outstanding as a romance or as film,” he noted, adding that “at times it gets awfully tedious and the talk is exceedingly long.” “There are bubbles in this film but champagne is mixed with baser stuff in about 50-50 proportions,” Otis Guernsey commented in the New York Herald Tribune. “The action has little more area than it did on the stage, but mostly Preminger has filmed the script as a photographed play The farce is so fragile, so pleasantly evanescent, that it might not have stood the strain of ordinary movie emphasis.”

But as Preminger had hoped, the reviews didn’t matter. Opening business was brisk, and when the Legion of Decency, always working hand in glove with the Production Code Administration office, gave the film a C rating, calling it “an occasion of sin, sophisticated smut,” it got even brisker. “I didn’t negotiate with the Catholic Legion of Decency,” Preminger said. “If they wanted to instruct Catholics not to see the film, fine. They had every right to do so. But I am not Catholic and they could not tell me what to take out of my picture.”50 State censorship boards joined in the attack. Three states—Ohio, Maryland, and Kansas—banned it outright. Preminger and United Artists took the case to a Maryland court. On December 7, 1953, Judge Herman Moser, describing the film as “a light comedy telling a tale of wide-eyed, brash, puppy-like innocence routing or converting to its side the forces of evil it encounters,” reversed the State Censor Board, ordering it to grant a license to the film.51 The Supreme Court of Kansas, however, unanimously upheld the decision of the state board of review to ban the film. Refusing to be silenced, Preminger and United Artists, at considerable cost, took their case before the United States Supreme Court—and won. On October 24, 1955, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the finding of the Supreme Court of Kansas.

In early July, after the film had broken box-office records at the Four Star in Los Angeles and in the other, carefully selected houses in the tryout cities, three theater chains, United Paramount, Stanley Warner, and National Theatres (by now divorced from the studios that had originally owned them), made the momentous decision to book The Moon Is Blue. By July 15 the film that had opened without the industry’s Seal of Approval was playing in two thousand large theaters across the country and was on its way to grossing $3.5 million, a considerable sum at the time. Preminger, Hugh Herbert, William Holden, and United Artists made a substantial amount of money.

“ The Moon Is Blue sounded the death rattle of the Legion of Decency and the Production Code,” conclude Leonard Leff and Jerold Simmons in their history of Hollywood censorship.52 Joe Breen’s battle with Preminger was the censorship czar’s “last great orchestral flourish,” as Breen’s lieutenant Jack Vizzard commented.53 Not surprisingly, on the eve of his downfall Breen was awarded an honorary Oscar at the Academy Awards ceremony on March 25, 1954. (That night, The Moon Is Blue was nominated for three awards, including a best actress nod for Maggie McNamara.) On October 15, 1954, Geoffrey Shurlock succeeded Breen. On June 28, 1961, Shurlock personally issued a Certificate of Approval to The Moon Is Blue, and at that point United Artists rejoined the Motion Picture Association. The Production Code Administration operated with diminished impact, a situation Shurlock himself approved of, until November 1,1968, when a system of classification replaced it and the former enforcers of the Code became the honchos of the Code and Rating Administration.

In what was the decisive battle of his professional life, Preminger once again had the advantages of both good timing and good luck. As Otto had suspected and counted on, after twenty years of exerting an inordinate influence over the moral and visual content of mainstream American films, both the Production Code Administration office and Joe Breen himself—flamboyant, feisty, and personally likable—were ripe for a fall. All they had needed to push them off their pedestal was a David with the courage to sling a strategic stone at the Goliath of an outmoded document of censorship. Dr. Otto Ludwig Preminger of Vienna cast himself in the role, which he played with unstoppable conviction. His motives were a blend of idealism (Preminger’s objection to censorship in both its immediate and long-range consequences was genuine) and financial common sense (he knew in his bones that a public confrontation with the enforcers of the antediluvian Code could be worth its weight in box-office gold). As a spokesman for free speech, a defender of freedom in artistic expression, and an adversary of the straitlaced Code, Otto demonstrated redoubtable stamina and style.

Amid the hullabaloo, the film itself seemed to be almost beside the point, a mere parenthesis. The narrative of the film’s reception in 1953 provides important insights into the moral codes of Eisenhower’s America— only a deeply puritanical society could have regarded this talky innocuous comedy as sophisticated smut, a cause for alarm. The characters do indeed discuss the protocols of seduction with a “modern” insouciance unusual for the era, but the deeply conservative film in no way threatens the social or sexual status quo. “Now of course it all seems so innocent and even sweet, and so very old-fashioned,” Hugh Herbert’s daughter Diana said. “But in those days you did not hear words like ‘virgin’ and ‘seduced’ and ‘pregnant’ on stage or screen. Today you’d have to add strange sex scenes to get the same kind of reaction. In London critics and audiences weren’t as shocked; if anything they were amused by the American reaction. For many years now the primary market for the play has been high schools.”54

Preminger’s direction reinforces the material’s fundamental tameness. When he submitted as part of his defense of the film’s morality the argument that “there is not a moment of passion,” Otto wasn’t kidding. Never for an instant do the characters or, for that matter, the director, lose their cool. Working in a strict minimalist vein of straightforward continuing editing, objective camera movement, and centered compositions, Preminger transfers his hit play into the more durable form of celluloid with unimaginative competence. His approach indemnifies the material against any possible charge of licentiousness, but it also suppresses a liberating comic spirit, precisely the qualities of spontaneity and friskiness that might have been teased out of the show’s premise.

Preminger expands the action to include scenes in the shopping concourse of the Empire State Building; Don Gresham’s office; a taxi; the hallway, elevator, and fire escape in the building where Don lives; and the living room and bathroom of David Slater’s apartment. Throw in some fog and rain briefly glimpsed outside the windows, and that’s about it for scenic amplitude. “Don’t spoil the customers” might have been Preminger’s mantra to his art directors, Nicolai Remisoff and Edward Boyle. As a result the story unfolds in an airless environment, a world apart that is curiously unpopulated. When Don and Patty meet on the observation deck of the Empire State Building, for instance, no one else is there. (In the rhyming scene at the end, however, Preminger in a nice touch includes tourists—the stars of the German version of the film.) However, the film’s two major settings, the apartments of the swinging bachelor and his suave upstairs neighbor, are intelligently designed. Don’s modern bachelor pad, with abstract art on chaste white walls (a décor reflecting Otto’s regard for the International Style), is meaningfully contrasted with the Continental luxury (heavy drapes, museumlike representational paintings, Old World furniture, a decadent bathroom with a marble-lined tub) of Slater’s apartment.

On its own merits, rather than as a specimen in a censorship furor, The Moon Is Blue long ago failed the test of time. Even so, regarded with patience and generosity, it has an antique charm. In the short term the film made Otto money and established his bona fides as a cunning independent filmmaker. But in the long term this ephemeral comedy that happened to light a spark in an age of innocence drove another nail into the director’s always precarious critical standing. Unfairly, Preminger bashers have taken it as a paradigm of the director’s entire portfolio: not-so-good films on currently controversial topics that have no resonance once their “hot” subject matter ages.

As he was starting his career as an independent producer-director, Preminger was also getting adjusted to a new wife and to an unaccustomed role as a stepfather to Sandy. Because of Otto’s six-month annual release from Fox, the Premingers were peripatetic. The new couple, however, had different preferences about where to live. Otto favored New York and wanted to spend as much time there as he could; Mary, who liked Los Angeles, wanted to stay in one place and in a house of her own where she could paint and sculpt. “Otto was a big hotel liver,” as Sandy, now known as Gilbert Gardner, recalled,

and at the beginning of the marriage we were with him in suites at the Carlyle, the St. Regis, and the Ambassador. Later Otto had an apartment at 40 East Sixty-eighth Street; basically, nobody but me lived there. I was studying acting with Stella Adler at the time. The first time Otto brought my mother to Los Angeles, after they were married, he rented a small house overlooking the Bel-Air Hotel. And something happened that worried her. Gregory Ratoff stayed there for five days and played cards the whole time; Sam Spiegel was there much of that time too. It was all part of Otto’s Hollywood buddy system, which my mother didn’t understand.

After a period of moving around, Otto rented Anatol Litvak’s pink palace in Malibu—Litvak had built it in 1936 for Miriam Hopkins, his lady friend at the time. Litvak began to rent out the house in the early 1950s, and after a while that was Otto’s and my mother’s base when they were in Los Angeles. The house had an intercom system that was state-of-the-art. Otto employed a couple who ran the house. In my time Otto gave five or six major parties, sometimes with as many as three hundred people gathered on the huge deck and in the dining room. Cars would be lined up by valets. And there were a huge number of caterers. These were gatherings of people of great worth and value: Chaplin, who became a special friend of mine; Cole Porter—I met him four times, but he never remembered me; Tyrone Power; the Henry Fondas; the David Selznicks; James Stewart. I was kind of shocked by the excess, the ostentatiousness. Rock stars now run their lives in that fashion. This was the Old Hollywood, a very insular way of life.55

At the beginning, as Gardner recalled, my mother and Otto were really fond of each other and Otto was fatherly to me. He wanted me to be a part of his business, and while the marriage lasted I worked in some fashion on all his projects. He spent time with me; he wanted to spend time with me. He would always ask me to go to the theater with him. There was very little of the temper at home. That was reserved for younger actors, for business dealings, and with production people. Mostly, I thought the temper was an act. At home he really was not that way, but he was patriarchal, and he was European. He liked to have his butler take care of his clothes, and he expected his wife to run his household, to arrange dinners in the proper way. Fortunately, Mary was a good party giver. She had the grace and upbringing to be a good hostess.56

With (left to right) French actress Suzanne Dadelle, Mrs. Gary Cooper, Kirk Douglas, and Otto’s stepson Sandy Gardner, New York, December 1955.

From the start, however, the marriage had a shaky foundation. Increasingly preoccupied with the hubbub over The Moon Is Blue, Otto was a longdistance husband, and although Gardner did not know it at the time, from early in the marriage his mother and stepfather were not faithful to each other. In a basic way the marriage was a business arrangement. Otto wanted a hostess for his A-list Hollywood parties, and Mary, who had already weathered three failed marriages, wanted financial security.

Since he had signed his new contract with Fox, Preminger had managed to avoid making any commitment. But when Darryl Zanuck called Otto when he was in New York preparing for the June opening of The Moon Is Blue, asking him to direct a western with a nifty pulp title, River of No Return, he realized the time had come to pay the piper. Understandably, “after the complete freedom I had enjoyed making The Moon Is Blue as an independent and the almost-freedom Howard Hughes had given me in order to take revenge on an actress,” Otto was reluctant to return to a factory job.57 Because for good reason he had trouble picturing himself out on the open range, he was not thrilled at the prospect of directing a western.

Preminger wasn’t the only one who questioned Zanuck’s assignment. Stanley Rubin, the film’s producer, was also doubtful. “I wanted Richard Fleischer, who had just done such a terrific job on Narrow Margin [a first-rate film noir Rubin had produced the previous year at RKO], but he wasn’t available,” as Rubin recalled. “It was at that point Zanuck mentioned Otto Preminger. I was familiar with his work, of course: I loved Laura and I felt he was talented but not the man for our piece of Americana. At a meeting with Zanuck’s assistant Lou Schreiber, I said Otto was wrong, his skill was in contemporary sophisticated melodrama and comedy. I saw Wild Bill [William] Wellman or Raoul Walsh or Henry King instead. When I found that Preminger had a pay-or-play commitment, I realized I was fighting a losing battle.”

Once Preminger read the screenplay, however, his attitude changed. He liked the story, which Rubin had developed with a series of writers.

A friend of mine, Louis Lantz, [Rubin recalled,] had a great idea. He wanted to steal the premise of Bicycle Thief, in which the hero finds that after his bicycle is stolen he has no way to support himself and his son, and transport it to the American West. When our hero in the West has his horse and gun stolen, he too can’t support or protect himself and his son. Lou wrote a good treatment and first draft, and I hired Frank Fenton for the final draft. Originally, the plan was to make the film on a modest budget; but as we were working on the first draft, Fox got “married” to CinemaScope [the first two Fox films in the new wide-screen process, The Robe and How to Marry a Millionaire, had been released in the fall of 1953]. “Your movie lends itself to CinemaScope, and your budget is going to go up,” Zanuck, delightful and stubborn, a boss in the days when there really was a boss, told me.’58

Preminger welcomed the chance to shoot in CinemaScope, and he approved of the stars Zanuck and Rubin had already cast: Robert Mitchum for the horseless hero (Otto had forgiven, or more likely forgotten, their fracas during Angel Face) and Marilyn Monroe for the role of a saloon singer who hooks up with the hero and his son. Zanuck, famously ambivalent about Monroe, had resisted when Rubin pushed for her. “He was suggesting others. He mentioned Anne Bancroft in particular, but Monroe had the combination of qualities—sexiness, beauty, vulnerability—I wanted in the part. She was the only one I wanted,” Rubin said, “and I prevailed.”

When Otto flew in from New York, Rubin took him to lunch at the Fox commissary. “I made the mistake of youth—at thirty-six I was the youngest producer on the lot, and I was honest,” Rubin recalled. “I told Otto he was not the director I was looking for. What did that candor gain me? It put Otto on edge from our first meeting.” But as they began to confer about the songs Monroe would sing and about the production schedule, and after they traveled to Canada to scout locations at Banff and Lake Louise, Rubin grew fond of Preminger. “I felt he really wanted to do the picture, and that it was not just a contractual obligation.” Before production was scheduled to begin in the late spring, Zanuck made a change in the script that neither Rubin nor Preminger agreed with. “It wasn’t anything major, as I recall, but we felt we had to address it with Zanuck,” Rubin said. “I set up a meeting, expecting Otto to join me in the battle, and more likely, to lead it. But his behavior totally surprised me: he did not open his mouth. It was the only time I ever saw Otto fade into the wallpaper. I won the battle, but I won it alone.” It was only afterward that Rubin learned of Preminger’s long-past falling out with Zanuck: “Could Otto have been afraid of starting up again with Zanuck? I did not feel any tension between them, however, and fifty years later I still don’t know why Otto clammed up as he did in that meeting.”59

For his big-budget CinemaScope western Rubin was able to schedule twelve weeks of preproduction, during which Marilyn Monroe rehearsed and recorded her musical numbers, and a forty-five-day shooting schedule. Location scenes in Canada were shot first. At the end of June (only weeks after The Moon Is Blue had opened), Preminger and the cast flew to Calgary from Los Angeles. As a publicity gimmick, the cast traveled eighty miles on a specially commissioned train from Calgary to the Banff Springs Hotel. Crowds lined up along the route to catch a glimpse of Monroe, who as the star of the recently released Niagara and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and the upcoming How to Marry a Millionaire was on the verge of becoming the world’s most famous blonde. Traveling with Monroe was her acting coach Natasha Lytess, “passing herself off as a Russian, for reasons of her own,” according to Otto, who was certain that in fact she was “a German.” 60

Under any circumstances, Preminger and the always tardy Monroe, who also seemed unable to memorize lines, could never have gotten along. But Natasha, hovering over Monroe’s every line and gesture, stoked Otto’s temper to the boiling point. Before and after each scene Monroe would be locked in private conference with Lytess, the star’s self-appointed codirector as well as her surrogate mother. According to instructions from Lytess, Monroe would either request or refuse to do another take. Maddeningly, Lytess had convinced Monroe that her reputation as a dramatic actress would rest on her ability to enunciate each syllable of every line of dialogue with exaggerated emphasis. “She rehearsed her lines with such grave ar-tic-yew-lay-shun that her violent lip movements made it impossible to photograph her,” Preminger complained. “I pleaded with her to relax and speak naturally but she paid no attention. She listened only to Natasha.” 61

The circumstance of Otto Preminger taking his marching orders from a pretentious acting guru and a desperately insecure actress surely conforms to at least two of Aristotle’s criteria for tragedy, capable as it is of eliciting both pity and terror. But the harassed director won little support from the crew. “Otto was a complete pain in the ass,” according to Paul Helmick, the assistant director and unit manager. “[He was] vicious, impatient, very crude to people.” 62 When he could no longer tolerate the Marilyn-Natasha onslaught, Preminger called Stanley Rubin in Los Angeles to demand Natasha’s removal. After her coach was dismissed, Monroe called Zanuck to demand her reinstatement and the next day Lytess was back on the set. “Otto had the power to get Natasha off the set, and Marilyn had the power to get her back,” Rubin recalled. 63 Zanuck phoned Otto to commiserate, but also to reinforce the fact that Monroe’s box-office pull was, in effect, paying his $65,000 director’s salary. Flummoxed and humiliated, and realizing he was stuck with Natasha, Otto began to turn his rage onto Monroe. “Deriding her talent as an actress and recalling [her] days as one of Sam Spiegel’s ‘house girls,’ he advised her to return to her ‘former profession,’ ” Monroe’s biographer Barbara Leaming claimed. 64 As Paul Helmick observed, “It was the biggest mismatch I’d ever seen. [Monroe and Preminger] absolutely detested each other.” 65

Preminger survived because his erstwhile adversary, Robert Mitchum, was equally impatient with Monroe. Immune to his costar’s sex appeal—she wasn’t his type—Mitchum more than once called her bluff. “He would slap her sharply on the bottom and snap, ‘Now stop that nonsense! Let’s play it like human beings,’ ” as Preminger recalled.66 Before a number of scenes Mitchum was able to startle Monroe into speaking in her own voice, delightfully slurred and intimate. In the finished film it’s possible to see the shots where Mitchum got to her and the ones where he failed to.

Monroe and Preminger were both soothed by the presence of Tommy Rettig, a delightful eleven-year-old cast as Mitchum’s son. “Marilyn loved the boy, and they had a sweet, warm relationship,” Rubin said. “Otto respected Tommy’s professionalism; when Marilyn would go up in her lines, and a scene might have to be shot over twenty times, the boy would be word-perfect every time.” 67 Tommy’s confidence, however, faltered after Natasha repeatedly told him that child actors were in danger of misplacing their talent unless they took lessons and “learned to use their instrument.” Tommy began to forget his lines and then, several times, burst into tears. It didn’t take long for Preminger to locate the source of the boy’s discomfort. Infuriated, he once again demanded Natasha’s banishment. And once again, at Monroe’s insistence, Natasha reappeared. Preminger, however, spoke to the cast and crew about Natasha’s abuse of Tommy and as he gleefully reported, “Everyone in the company [except, of course, Marilyn] cut her dead.” 68

Preminger also had to contend with rainy weather and dangerous stunts on the Bow River. For the most hazardous scenes, stunt doubles stood in for the stars, who worked only on a raft tied securely to the riverbank. Still, Mitchum’s heavy nightly intake of alcohol and Monroe’s perpetual distraction rendered them unsuited for scampering on rocks made slippery by rushing water. Near the end of the location shooting Monroe suffered a serious twist to her leg that kept her off the set for a few days. When she returned to Los Angeles in early September to shoot the interior scenes at Fox, she was on crutches.

Tensions did not ease once the company began working in the studio. “At that point I was on the set every day, and I saw Otto bully Marilyn and some of the crafts people, some of the lower ones,” Rubin said.

I never saw him scream at Natasha, but in speaking to Marilyn he would be just below yelling—in front of everybody. It was a frontal assault. I saw her in tears near the end of shooting. When we were scheduled to do close-ups on the raft on the tank stage and she knew she was going to be drenched, with water pouring all over her, she wouldn’t come out of her dressing room. Otto was enraged. He started screaming at his full lung power and he pounded the back of his chair, demanding Marilyn’s immediate appearance on the set. I talked Marilyn down—she may have been frightened. When she came out Otto was seething, and he continued to hurl insults, berating her for being selfish and unprofessional. He wouldn’t let up; everyone could see that he despised her, and it seemed to be personal as well as professional. Marilyn and I got on nicely because we had a common enemy: Otto Preminger.

Location shooting in Canada for River of No Return, Preminger’s first film in CinemaScope.

Rubin’s examination of the dailies confirmed his original belief that Preminger had been the wrong choice. “An aura that would have been natural for a Raoul Walsh, who was steeped in Western lore, wasn’t there,” Rubin concluded. “A feeling, a tone I was looking for, and that was in the script, wasn’t there. Otto and I had a bad fight about a scene with Monroe and Mitchum in the woods. Otto said it would work fine; I felt an element had been lost. In the first and final analysis, Otto and I were not meant for each other—our personalities were not attuned. Otto was bigger than life, and I am life-sized.” 69

Despite the embattled atmosphere Preminger finished on schedule, on September 29, and within Rubin’s original budget. Once shooting was completed, Otto began to edit with Lou Loeffler, whom he trusted, but before the end of postproduction he left for Europe; working alongside Loeffler, Rubin finished the film. “We made some changes and a few retakes were shot by Preminger’s friend, Jean Negulesco,” Rubin said.70 As Otto recalled, “After River of No Return I decided not to work ever again as a studio employee. I paid Fox $150,000 to cancel my half-year contract.”71

Otto’s leaving before the final cut was completed was a declaration of independence, but during filming he had been engaged by the project. The story of a father, just released from prison, who learns to love a son he has not known no doubt caused Otto to reflect on his own unknown son Erik, now nine and being raised by his mother. The scenes between father and son tentatively reaching out to each other are the strongest in the film, beautifully played by Robert Mitchum and Tommy Rettig.

Preminger discovered that shooting in CinemaScope supported his usual preferences for long shots and minimum intercutting. “It is actually more difficult to compose in this size,” he said. “Few painters have chosen these proportions, and somehow it embraces more, we see more widely, and it fits into long takes better. On the wide screen, abrupt cuts disturb audiences.”72 On a first outing in the wide-screen format in which he was to become a master, Preminger and his cinematographer Joseph La Shelle revel in panoramic vistas: high-angle shots of the raft floating on the river between canyons of massive rock; low-angle shots of Indians massed threateningly on the tops of high cliffs. The opening scene, which Preminger and La Shelle design as a fluid tracking shot that follows Mitchum as he rides through a tent community buzzing with activity, reveals the increased possibilities in CinemaScope for long takes and deep focus.

There is no way, however, that as a director of a western Otto Preminger could ever be mistaken for John Ford. A fight scene, in which two roughnecks suddenly appear, without a horse, in the middle of the wilderness and begin to attack the hero, is perfunctorily staged and edited. An Indian attack is only marginally more convincing. (The film’s reactionary, reflexive treatment of faceless Indians on the warpath is standard for the era. Their individuality erased, their grievances never addressed, their cameo appearances cued by dissonant chords on the sound track, the Indians function as pure motiveless malignity, a threat to the white man’s hegemony.) Problematic, too, is the occasionally faulty match between studio and location shots. A scene in a cave smells of studio artifice, and repeated process shots of the characters on the raft fall well below the technical standards of the time.

Tommy Rettig (eleven years old) helped Marilyn Monroe, who detested Preminger and her role as a chorus girl, through the ordeal of filming River of No Return.

Otto stumbled with Monroe. The actress herself frequently claimed that River of No Return was her worst film. It isn’t, but it’s easy enough to see why she was unhappy. Aside from her dislike of the director, the role of a saloon singer longing for love and respectability reinforced stereotypes she was already determined to resist. And in a story of masculine rituals, her whore with a heart of gold is not only a cliché, she is also largely irrelevant. In most of her scenes with Tommy Rettig, in which she speaks in her natural voice, and in her musical numbers, Monroe is captivating in ways that only a born movie star can be. But in the far more numerous scenes with adult males, she delivers her lines in the style demanded by Natasha. Otto’s failure to knock the affectation out of his misguided star is a notable lapse in his careerlong assault on overacting.