Otto’s haste to be done with Monroe and Fox was due to his eagerness to launch into his second independent production, an opera with an all-black cast. He was counting on the likely fact, as he had with The Moon Is Blue, that no major studio would take the risk of making Carmen Jones, an adaptation by Oscar Hammerstein II of Georges Bizet’s 1875 opera Carmen that had been an unexpected hit on Broadway in 1943. Otto was convinced he could transform Bizet’s perennially popular opera, with its ravishing melodies, sex-driven characters, and compelling story, into a realistic film that had every chance of stirring up controversy. It was not an easy sell, however.

From the moment Oscar Hammerstein had heard Bizet’s opera in concert at the Hollywood Bowl in 1934, he had seen its potential as a musical play—a show for Broadway rather than the opera house. In his adaptation, set in North Carolina and Chicago during World War II, Bizet’s fiery heroine becomes Carmen Jones, a worker in a parachute factory who seduces and abandons Joe, a soldier, before moving on to her next conquest, a prizefighter, Husky Miller. Joe, driven mad by Carmen’s desertion, strangles her. Hammerstein eliminated recitative, noting that the composer and his collaborators “originally wrote Carmen with spoken dialogue scenes between the arias. The work was not converted to ‘grand opera’ until after Bizet’s death [with music written by Ernest Guiraud].”1 Nonetheless, Hammer-stein had difficulty finding investors. Billy Rose, a scrappy impresario with deep pockets, decided to take a chance on the show, which he presented on Broadway on December 2, 1943, to a warm reception. Carmen Jones had a substantial run of 502 performances followed by an eighteen-month national tour.

When he had seen it, Preminger was impressed more by the idea of the show than what Hammerstein had done with it. Inaccurately, he dismissed the Broadway Carmen Jones as a series of “skits loosely based on the opera” and recalled that the score had been “simplified and changed so that the performers who had no operatic training could sing it.”2 In fact, Carmen Jones adheres closely to the opera’s structure and was sung operatically In his film, Preminger was intending to disregard “Hammerstein’s revue” as well as the opera’s libretto by Meilhac and Halévy and to return to the original source, the 1845 novel by Prosper Mérimée. To write the script he hired Harry Kleiner, his former student at Yale, instructing him to open up the material beyond the limited settings of both the opera and Hammerstein’s adaptation. (In the “revue,” Hammerstein sets Act I in a parachute factory and improbably squeezes Act II onto the terrace of a black country club.) “I had decided to make a dramatic film with music rather than a conventional film musical,” Preminger said, and to maintain movie realism he intended to shoot as much of the film as he could on location.3

After his success with The Moon Is Blue, Preminger was counting on the support of Arthur Krim and Robert Benjamin at United Artists. But at a lunch at “21,” the two men, having examined the financial history of all-black films and concluding that the project was not economically viable, declined. “Sorry, Otto, but this is too rich for our blood,” they said.4 Surprised by their reaction, Preminger quickly offered the project elsewhere. Again the response was negative.

As he continued to search for backers, Otto did something he had never done before and would never attempt again. In October 1953, he directed an opera for the New York City Opera, the American premiere of a work by Gottfried von Einem based on The Trial, by Franz Kafka. For Preminger the material was a radical departure: Kafka’s novel, a nightmarish allegory of a man accused of a nameless crime, is not concerned with the realistic kind of trial and the real-world legal issues that were Preminger’s usual bailiwick. But Otto welcomed the challenge of directing an opera for the stage as a way of preparing for Carmen Jones. “Mr. Preminger, being a believer in the work of the New York City Opera, is charging a considerate fee, but it would nevertheless be higher than any previous fee paid to a stage director by the City Opera,” an article in the New York Times on September 21, 1953, noted. On the whole, Otto’s production received stronger reviews than the opera itself.

Olin Downes in his New York Times review on October 23 praised “a carefully prepared and extremely capable performance” but expressed disappointment in the opera. “Its musical substance is of the slightest… . Could any librettist, any composer, have turned this work of Kafka into a compelling music drama? One might, the Alban Berg of Wozzeck. But he has gone, and it is doubtful if the future will produce another like him.”

Despite many turndowns, Otto continued to believe in Carmen Jones. Salvation came finally from a perhaps not unexpected source: Darryl Zanuck, who had heard of Preminger’s difficulties placing the project and asked to see the script. After reading it, he promptly offered financing. Fox would be providing the funds, but Preminger would operate as an entirely independent filmmaker.

Zanuck believed Carmen Jones had blockbuster potential. But Joseph Moscowitz, the head of Fox’s business affairs in New York, did not, and for weeks he avoided meeting with Preminger. When Zanuck finally forced him to complete the deal, Moscowitz refused to offer more than a meager $750,000. After finally signing a contract in December 1953, Preminger began what was to be a prolonged preproduction process. He started to scout possible locations, always one of his favorite activities. He hired his crew. Veteran Sam Leavitt would shoot the film. The musical director would be Herschel Burke Gilbert, who had composed the score for The Moon Is Blue. Herbert Ross would choreograph. All the while Otto continued to huddle with Harry Kleiner on refining the script, making sure drama rather than music remained the focus.

And then, on April 19,1954, six weeks before he was scheduled to begin shooting, Preminger had another run-in with Joe Breen, who in his final months at the head of the Production Code Administration office seemed determined to even the score over Otto’s victory with The Moon Is Blue. After he read the script, Breen was livid. His objections to The Moon Is Blue had been entirely in what the characters said, in their mental attitude toward sex, whereas his complaints about Carmen Jones were visual as well as verbal. Carmen lives by her erotic skills, titillating her men with seductive body language and verbal come-ons—there was no question that as written, the character was intended to be sexually provocative in ways that violated contemporary Hollywood standards. Breen to his horror fully grasped that Otto, capitalizing on the racist stereotype of blacks as sexually superior to pale Anglo-Saxons, was intending to produce one hell of a hot-blooded movie. Breen cited the script’s “over-emphasis on lustfulness,” lodging particular complaints against Carmen sliding down Joe’s body after he has lifted her up; Carmen adjusting her stockings as Joe watches; and Joe waking up in Carmen’s bed. “We cannot see our way clear to approve detailed scenes of passion, in bedrooms, between unmarried couples,” Breen fulminated. Breen overall was outraged by the film’s apparent neutrality, “the lack of any voice of morality properly condemning Carmen’s complete lack of morals.”5

Because he had made his point in the fight over The Moon Is Blue; because he was relieved at last to have found backing; and because, unlike the comedy, which had needed a fracas to put it over, Carmen Jones had far more than some sexy images to entice mid-1950s moviegoers, Preminger agreed to make some minor adjustments. But he drew the line at Breen’s objection to a lyric, “Stand up and fight like hell,” sung by the prizefighter Husky Miller. Here he would not budge. Neither would Breen. A flurry of memos flew back and forth between Fox and the Production Code Administration office. Preminger applied to the board of the Motion Picture Association of America and won his case. But at the same time he agreed to shoot two versions of two scenes Breen had found offensive—in both cases, Preminger’s original versions survived.

Otto was unfazed about violating sexual taboos, but in 1954, at a time when blacks had virtually been written out of mainstream American films, he was sensitive to issues of racial representation. Aware of the value of providing employment to performers who had been overlooked, he was at the same time alert to the possibility that the all-black world of the film could reinforce prejudice. He was concerned, too, that black characters speaking in dialect and impelled by atavistic sexual urges could be potentially offensive to some black viewers. “ Carmen Jones was really a fantasy, as Porgy and Bess was,” Preminger said. “The all-black world shown in these films doesn’t exist, at least not in the United States. We used the musical-fantasy quality to convey something of the needs and aspirations of colored people.”6

At Zanuck’s urging, Preminger sent the script to Walter White, president of the NAACP. White’s response, recorded in a memo from Preminger to Zanuck, was reassuring. “While White indicated that he principally is opposed to an all-Negro show as such, because their fight is for integration as opposed to segregation in any form, he likes this particular script very much and has no objection to any part of it.”7

Preminger assembled his cast quickly. For Joe, the male lead, he signed Harry Belafonte, a good-looking folk singer who had recently popularized calypso and in 1953 had made his film debut in Bright Road and won a Tony Award for John Murray’s Almanac. In the supporting role of Frankie, Carmen’s good-time, smart-talking friend, he hired Pearl Bailey, who had appeared in two minor films but had become popular as a band singer and on Broadway in 1945 in St. Louis Woman. As the prizefighter Preminger chose Joe Adams, a strapping Los Angeles disc jockey.

For Diahann Carroll, then a nineteen-year-old singer from New York, auditioning for Preminger was a terrifying experience. “I had never before encountered power on such a grand scale,” she recalled. “Otto Preminger was seated behind the longest desk I had ever seen … his office was the size of a hotel ballroom.”8 Preminger, catching her off guard, asked her to read for the title role. On the spot she was to prepare a scene in which Joe (read by James Edwards, who only a few years earlier had seemed about to become the first black leading man in American films) paints Carmen’s toenails. Stunned by Preminger’s order for her to remove her shoes and stockings, she could barely focus on rehearsing with Edwards, “one of the most seductive men I have ever met.” When Preminger returned, she stumbled through the scene.

Nothing in my young life had prepared me for this kind of heavy sexuality, and I couldn’t begin to handle it, even on the level of “let’s pretend.” Sensing my discomfort, Preminger asked, blaring at me with his full force (but with a glint in his eyes), “Who ever told you you were sexy?” “No one! No one! I swear!” I answered quickly, looking him straight in the eye, somehow recognizing that both of us knew this was outrageous, and that a friendship had just begun. And then Otto Preminger, the bully extraordinaire, threw back his head and roared with laughter.9

Diahann Carroll didn’t get the part. But Preminger, who always appreciated people who could make him laugh, found a small role in the film for his new friend (she was to play Frankie’s sidekick Myrt), and he was to cast her in two future films as well.

Brock Peters, who, unlike the other performers Preminger had cast so far, was operatically trained, remembered “a surprisingly easy interview. I knew Preminger’s reputation, we all did. But when I saw him, in New York, he couldn’t have been more polite and gracious. He did not ask me to sing, but I could feel he was looking me over very closely. His blue eyes looked at me intently; I had the feeling those eyes could see right through you. My first impression was that here was a man who was all-knowing, and from that came the terrific power that he radiated.” At the end of the meeting Preminger cast Peters in the unsympathetic role of Sergeant Brown, a troublemaker attracted to Carmen and resentful of Joe. Peters was thrilled. “Film to a black performer back then seemed a long way away—the very thought of Hollywood was so remote, and so unattainable for black youngsters. We all felt we needed some kind of magic to make it happen.”10

As he was casting, Preminger scheduled a rehearsal period beginning on June 3 and planned to start shooting on June 24. But well into April two

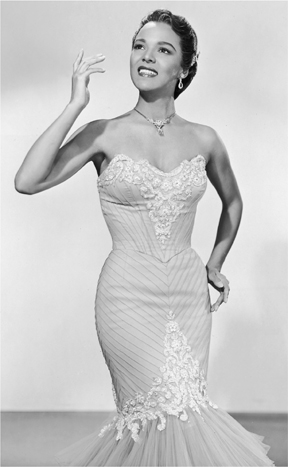

Dorothy Dandridge in a cameo appearance as herself, a sophisticated nightclub singer, in Remains to Be Seen, a year before Carmen Jones.

principal roles remained unfilled: Joe’s small-town gal Cindy Lou, and the star-making title role. In retrospect Otto’s casting of Dorothy Dandridge, a striking beauty and a performer with a lengthy résumé, would seem to have been a foregone conclusion. Born in 1923, Dandridge had been working professionally since the age of four. She appeared regularly in nightclubs, was on television in Beulah, and had had occasional roles in movies, beginning with a bit part in the Marx Brothers’ A Day at the Races in 1937. Typecast as an “exotic,” she had been seen in such minor films as Bahama Passage (1941), Drums of the Congo (1942), and Tarzan and the Jungle Queen (1951). However, in 1953 her appearance as a high school teacher in Bright Road had given her a new stature in the film community, and her career as a sultry chanteuse was flourishing. Preminger certainly knew about her; he had even seen her in a nightclub appearance in New York. But he thought she was too self-contained to play Carmen. He was looking for an actress with a drop-dead, come-hither sex appeal he did not feel Dandridge projected. Dan-dridge’s agents at MCA, who also thought she was the wrong type, were promoting another client, Joyce Bryant. But Dorothy wanted the role and was determined to get it.

Preminger agreed to see her only because of the intervention of his brother, Ingo, whose office at 214 South Beverly Drive was located in the same building where Dorothy’s personal manager, Earl Mills, also had an office. Mills showed Ingo a file of Dandridge’s photos and clippings and pleaded with him to get his client an interview. Ingo spoke to his brother, but when Otto called Mills to arrange a meeting he stated frankly that he didn’t think Dandridge was Carmen. “She’s too much like Loretta Young,” he told Mills.11

When Earl Mills and his anxious client arrived for the interview, Dorothy was too beautifully dressed, almost as if she had been compelled to confirm Preminger’s preconception of her. Perhaps being a little wicked, Otto suggested right off that she audition for the role of Cindy Lou, “a sweet, yielding girl,”12 which in fact is how he saw Dorothy. He wanted to give her the script, have her study the part of Cindy Lou, and then come back to audition. As Dandridge recalled, Otto was quite definite. “You cannot act the Carmen role. You have a veneer, my dear. You look the sophisticate. When I saw you I thought, How lovely, a model, a beautiful butterfly … but not Carmen, my dear.”13

Dorothy exploded. “Mr. Preminger, I’m an actress. I can play a whore as well as I can play a nun. If I could only convince you. I’m not a Cindy Lou. You don’t know what I’ve gone through.” Mills, sensing that Preminger liked Dorothy and “even wanted to help her,” silenced his client.14 He grabbed the script Otto was offering because he knew this would give them the chance for a second meeting.

Mills and Dorothy resolved to play their second act with Otto Preminger in a different key. At Max Factor’s, Dorothy and her manager borrowed a “messy looking black wig,” “an off-the-shoulder low cut black peasant blouse without a bra,” “a black satin skirt with a slit to the thigh without a girdle,” and “black high-heeled pumps.”15 Then Dorothy applied “sexy” makeup and began to practice a hip-swaying walk. To top off her impersonation Dorothy thought she needed “a tired look as if I had worn out a bed. I went to the gym and deliberately tired myself before I went to

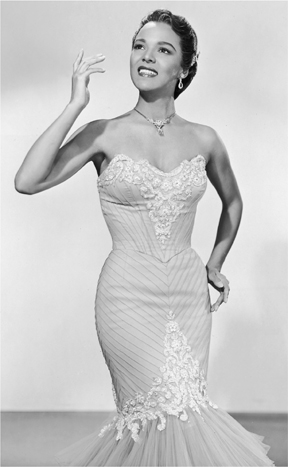

For her Carmen Jones screen test, Dandridge trans-formed herself from a ladylike chanteuse into Bizet’s rough-and-ready siren.

the audition.”16 As Mills commented, “She felt she might not get the role of Carmen but she was sure as hell certain that she wouldn’t be asked to do the role of Cindy.”17

When for the second time she and her manager entered Preminger’s office, by design just a shade late for their appointment, Dorothy with a provocative look in her “tired” eyes sashayed across the large room. “My God, it’s Carmen!” Preminger exclaimed, caught off guard by Dandridge’s transformation. “I had ceased to be the saloon singer, the lady, the sophisticate,” Dorothy exulted.18 Clearly delighted and no doubt realizing he had found his Carmen, Preminger asked her to move about the office, to open and close drawers, all the while gauging her gestures and body language on the sexual Richter scale. At the end of the meeting, he told her he wanted to shoot a screen test. To accommodate Dorothy’s nightclub schedule—she had a contract to appear at the Chase Hotel in St. Louis on May 3—he scheduled the test for mid-May When Dandridge was out of town, Otto found his Cindy Lou, Olga James, a Juilliard School of Music graduate with an operatic vocal range. “When I sang an aria for Preminger at the Alvin Theatre in New York, everybody applauded,” as James recalled. “It wasn’t a stretch for me. I was that character, a country-looking girl. I was just a little ingenue.”19

Dorothy’s test scene was the same one that Preminger had asked Diahann Carroll to perform. Playing opposite James Edwards, Dandridge gave a riveting performance, sexy and fearless. Preminger, who had already shot tests of Joyce Bryant and Elizabeth Foster in the same scene, was convinced, and on May 21 he announced that Dorothy Dandridge would play Carmen Jones.

At first Dorothy was exhilarated by having won the showiest leading role ever offered to a black performer in an American film. But a few days later she began to feel she wouldn’t be able to play it. “Too much stress. I feared my emotional system couldn’t handle it,” she recalled.20 Despite her veneer, Dorothy Dandridge was deeply troubled. She had had numerous affairs, often with white men who she felt had betrayed her, and she was guilt-stricken about her daughter, brain-damaged from birth. Eager to be taken seriously as an actress and frustrated by the kinds of roles she was offered, in the late 1940s she had studied at the Actors Lab, run by veterans of the 1930s Group Theatre. “The studios often sent young players to us, but Dorothy came on her own,” recalled Phoebe Brand, a Group actress who taught at the Lab.

She was very serious about acting. We taught Stanislavski, and unlike Marilyn Monroe, who also studied with us at the time and did not understand me, Dorothy absorbed our approach quickly. Morrie [Morris Carnovsky Brand’s husband] cast Dorothy as Kukachin in our production of O’Neill’s Marco Millions, and she was marvelous—we would have cast her in that role on Broadway. Dorothy was beautiful, startlingly so, but very fragile. She was a loner who didn’t make chums and was not easy to know. I remember once that she brought in her daughter; she carried her in. It was clear that she was crazy about her, but that she also felt so sorry and responsible for the child’s illness. There weren’t many blacks studying with us, though I wished there had been, but at that time the studios were not using black actors. We were surprised when she was cast as Carmen: who would have thought of casting her that way?21

Now, at thirty-one, not young by Hollywood standards, Dorothy had been handed the chance to act that she had long wished for, and she was panic-stricken. Her anxiety grew when a number of black friends cautioned her against playing a part that could reinforce negative preconceptions. “The Negro community is plagued by fears of its image,” Dorothy observed. “It has been so much the victim of stereotypes that it has developed an understandable sensitivity. I couldn’t bear to think I might turn in a performance that would be injurious to that perennial spectre, race pride, the group dignity”22 After several agonizing days in seclusion, she delegated Earl Mills to inform Preminger that he would have to continue his search for Carmen.

As soon as he heard, Otto drove over to Dorothy’s apartment on the Sunset Strip. He assured her, as Dorothy recalled, that she was indeed “a good actress … uninhibited, [with] natural free motions. By the middle of the evening I called him Otto.” By the end of the evening, Dorothy not only agreed to play Carmen, she “became [Otto’s] girl.”23 Dorothy’s biographer Donald Bogle was not certain that the affair began “at the beginning, as Dorothy claimed—you can’t trust everything in Dandridge’s autobiography. But it certainly started during the filming.”24

“Black women fascinated Otto,” as Willi Frischauer reported,25 while Dorothy had a decided preference for Caucasian men. For Otto, Dorothy personified a sexual ideal, the incarnation of his enduring, fetishistic devotion to black women. For Dorothy, Otto “was physical, all male—no problem there.” Aside from mutual racial and sexual attraction, however, there was much that would have drawn them together. Dorothy was enticed by Otto’s cultivated background and found his paternalistic attitude toward her wonderfully comforting. Her own father had abandoned her and her sister Vivian and she despised her mother, Ruby, an actress whose sadistic lesbian lover regularly beat both young women. Otto’s complexity, his combination of “both hardness and sensitivity,” also appealed to her.26 To Otto, the young woman’s vulnerability was as magnetic as her beauty. He knew he could draw a powerful Carmen from her, in the process transforming a damaged bronze Venus into a bona fide movie star, the first dark-skinned female star in Hollywood history. But he also sensed he would be able to exert control over her private life.

Beginning an affair with his star violated Preminger’s strict policy of separating church and state, but he succumbed this one time because his attraction to Dorothy was oceanic. “There was no doubt that he cared enormously about her,” Donald Bogle said. “Just as there was no doubt that Dorothy cared deeply for him. They were in love; on both sides, the feelings were overpowering. Both Otto and Dorothy, however, were concerned about race and the effect on their careers, and so there were no public or open displays, although there were rumors.”27 When they began their affair Preminger told Dorothy that he and Mary continued to live in the same house and cohosted parties but “were not exactly husband and wife.” “I think he had said we would be lovers ‘for the duration of the picture,’ but if so I ignored it,” as Dorothy recalled.28

As the last cast member to be signed, Dorothy had little time to collect herself. Music recording sessions in which she and Harry Belafonte were to be dubbed, respectively, by Marilyn Horne and La Verne Hutchinson, were scheduled for June I. (Neither Dandridge nor Belafonte could sing in the operatic range the score required.) Following three weeks of intensive rehearsals, shooting was now scheduled to begin June 30. “Otto knew he was dealing with people who had not been well treated by the industry, and he was fatherly and respectful,” recalled his stepson Sandy, hired to work on the film. (At the time Sandy did not know of Otto’s affair with Dorothy.) “Pearlie May [Pearl Bailey], respected by everybody, would joke and keep it light, and that also helped to take the heat off. She joked with Otto, who was just crazy about her. She was a doll.”29 “Preminger treated people like

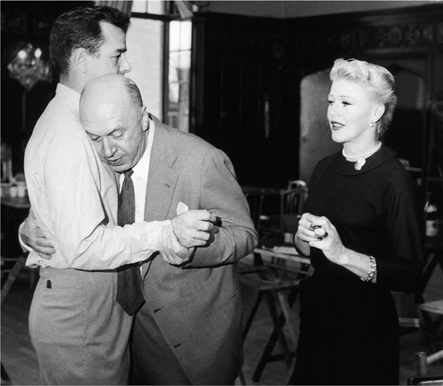

On the Carmen Jones set with Dorothy Dandridge, Harry Belafonte, and visitor Robert Mitchum. The rapport between Otto and Dorothy is apparent.

professionals,” Olga James maintained. “He rode a few people, yes, but that had nothing at all to do with race. There was no kind of fake camaraderie, or any kind of condescension whatsoever.”30

Preminger proceeded at a breakneck pace. Working from early morning until late at night, he put in longer hours than anyone else. Although still living with Mary and Sandy in Malibu, he spent some evenings at Dorothy’s apartment. The demands of a highly compressed shoot that moved between exterior locations in El Monte, California, doubling for the Southern locales, and interiors, including “Chicago,” filmed at the Culver Studios in Culver City, took their toll on the filmmaker, and perhaps inevitably he exploded a few times. The first episode occurred with a tense Brock Peters, “the new kid on the block,” who felt other cast members were “more sophisticated and experienced” than he was. “In one scene, Otto wasn’t getting what he wanted from me and he began to pressure me,” Peters recalled.

He was haranguing me, “You’re a New York actor, I expect better,” in front of everybody, in this terribly competitive environment. I was already insecure, and I thought his comment meant that somebody in Los Angeles should be playing my part. I was angry, and I lost it. I moved in on him. I didn’t know what I was going to do, but Pearl and somebody else held me back. Pearl said, “Hold your temper, or you will never work again.” I subsided quickly. We got past that, but then I was worried I’d be fired. A little later on—Otto was an equal opportunity haranguer—he went after Olga James, a glorious singer. The orchestra was assembled and she was to record her aria. He wanted Sprechgesang— he wanted it to sound more like speaking and less operatic, and when Olga didn’t immediately do what he felt he had clearly explained, he began to say terrible things to her out in the open. He just began to berate her in front of the full orchestra and all the singers; it was uncomfortable for everybody, and he didn’t seem to care or to notice.31

Olga James, as she remembered,

shouted back. “Don’t you yell at me,” I said. “How dare you?” When he lost his temper with me a second time, I snapped back at him again. He wanted to get a shot on location before he lost the light, and when I wasn’t quite ready he started in. But he was right and I was wrong: a professional would have understood about getting the light. He took charge, as he had every right to. “This is my picture,” he told me. Most of the time, however, Otto really was charming to all of us. Many people were afraid of him, though, and I noticed that he appreciated the ones who were not. In one rehearsal I remember Preminger saying with a big smile to Diahann Carroll, “You’re not intimidated by me at all, are you?” She wasn’t, and he enjoyed that.32

Vague rumors of an affair between Otto and Dorothy were floated within the cast (“I didn’t believe it when someone hinted about it,” Brock Peters said).33 But on the set the relationship remained strictly professional. “Preminger treated Dorothy very, very carefully, we all saw that, but once he did say something that made her cry,” Olga James recollected. “She went to her dressing room and cried like a lady”34 Working under enormous pressure—she had to awake each morning at five, and was on call for almost every scene—Dorothy kept to herself. By nature she was reclusive and untrusting, and relations between her and the other performers remained distant. “Harry was much more accessible,” Brock Peters said. “At first, Dorothy was extremely unfriendly to me, and I wondered if she thought I was a bad actor. I could see she was having a hard time, though, and that she was terribly insecure.”35

Dorothy’s retreats were also prompted by tensions with Pearl Bailey. “It was obvious to all of us that Pearl was jealous of Dorothy,” James said. “Most of us were theater trained, including Pearl, and Dorothy was from a different tradition. She was a very fine actress for film—she let the camera come to her. But Pearl didn’t think Dorothy was a good actress or singer. I don’t want to say anything disparaging about Pearl, however, who was a wonderful performer of a particular kind. White people loved her.”36 According to Donald Bogle, Bailey was “a pill, a holy terror like Ethel Waters and Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson. She was very competitive, and very jealous. She thought she should have played Carmen, as later she thought she should have played Bess [in Porgy and Bess].”37

After completing principal photography at the beginning of August, Preminger and the Fox publicity department gave Dorothy an all-out star buildup. Otto arranged for Philippe Halsman to photograph Dorothy for an article in Ebony magazine entitled “The Five Most Beautiful Negro Women in the World” (the others were Lena Horne, Hilda Simms, Eartha Kitt, and Joyce Bryant). He booked Dorothy, dressed in a Carmen costume of red skirt and black blouse, to sing two songs on October 24 on a live television spectacular, “Light’s Diamond Jubilee,” produced by David O. Selznick. On October 25, dressed in the same Carmen costume, she

Preminger and Pearl Bailey, one of his favorite actresses, on the set of Carmen Jones.

appeared on the cover of Life, again photographed by Philippe Halsman. To attend the world premiere at the Rivoli Theatre on October 28, Dorothy flew East with her sister Vivian. On opening night the klieg lights illuminating the sky were red, a tribute to the burning rose shimmering in fire, which was the image Preminger and Saul Bass had designed as the film’s logo. When Dorothy, alone, stepped out of a limousine to a barrage of flashing lightbulbs, she smiled radiantly. “If ever Dorothy looked happy, it was this night,” Donald Bogle noted.38

Her reviews were sensational. “She comes close to the edge of greatness,” Archer Winsten proclaimed in the New York Post. “Incandescent,” Newsweek hailed. According to Time, “she holds the eye—like a match burning steadily in a tornado.” “Dorothy Dandridge lights a blazing bonfire on the screen,” wrote Otis Guernsey in the New York Herald Tribune. Hedda Hopper raved that she “got so excited she burned a big hole in the front of [her] dress. Yes, the film is that hot.”39

Creating a sizzling Carmen in collaboration with his lover, a frightened actress, Preminger achieved one of the triumphs of his career, and over fifty years later Dorothy’s performance remains vibrant, and beyond either stereotype or vulgarity. For the first time in a mainstream American film Preminger had revealed a black woman’s potent sexuality. And in 1954 the erotic force that he helped Dorothy to unleash gave the film a tingle of danger, a shivering, “forbidden” undertow. Dorothy’s Carmen, sexually restless, forever on the prowl and forever dissatisfied, knows and controls her value in the sexual marketplace. She’s cunning in her ability to manipulate male desire, but unlike a man (Otto Preminger, for instance), for whom sexual conquest is a natural right, a way of seizing and maintaining power, Carmen is doomed: she’s too sexy to live. Drawing on his intimate knowledge of her, Preminger directed Dorothy to line Carmen’s sensuality with an underlying melancholy, and her performance is infused with the actress’s own wounds, her history as a black woman both rewarded and bruised, lionized and punished, for her beauty.

Knowing instinctively how to “let the camera come to her,” Dorothy with her director’s help pitches her acting precisely for film rather than the opera house or the Broadway stage. When she sings (with Marilyn Horne’s voice), the show, as Preminger intended, doesn’t stop for vocal display. For this down-to-earth Carmen singing is only one of her modes of seduction.

In 1954, in addition to being sexually and racially transgressive, Carmen Jones was also an artistic gamble. Preminger’s goal, turning an opera into a realistic dramatic film, was all but unprecedented at the time and, at least in prospect, insurmountably paradoxical. To make the film conform to the visual codes of movie realism he had to declare war on the conventions of both musical films and opera. Although he could have chosen to protect the unreality of musical performance by embedding the songs in artificial settings, he reasoned that a tinseled mise-en-scène that would be appropriate for light material would be jarring for a dramatic story. And it might alienate or puzzle the general moviegoing public he was hoping to reach.

To translate Carmen into a full-fledged film with popular appeal, he had to find ways of “naturalizing” Bizet’s score. The wisdom of his approach is revealed in Carmen’s first aria, “Dat’s Love” (“Habañera” in the opera), performed in an unmusical setting, the cafeteria of the parachute factory where Carmen works. As she sings, Carmen places food on her tray, exchanges greetings and insults with co-workers, and cozies up to Joe, her next quarry. Preminger’s direction, treating singing as a realistic, casual activity, an extension of speaking, significantly closes a breach between the imperatives of movie realism and those of musical performance.

Although Preminger was everywhere prepared to sacrifice musical purity for dramatic impact, he nonetheless filmed musical performance tactfully, refusing to allow the language of film—editing, camera movement, lighting—to compete with or to artificially enhance the score. His restrained approach works beautifully for the intimate songs; for the big production numbers, however, Preminger’s invisible movie realism is occasionally too tame. In a scene in a café, for instance, when Pearl Bailey launches into a rousing rendition of “Beat Out Dat Rhythm on a Drum” (“Gypsy Song” in Bizet), the camera remains on a group of characters at the bar as dancers are glimpsed in deep focus. In the absence of intercutting or reframing the audience is never allowed to appreciate the energy of the dancers. Preminger handles “Stan’ Up and Fight” (“Toreador Song” in Bizet), the entrance song for the prizefighter, in a similarly sedate way, with the camera placed at a distance from the action. But the number calls for a touch of razzle-dazzle, a bit of cinematic bravura in which at least momentarily the film itself should spin along with the musical rhythm.

Preminger’s staging of Joe’s aria, “Dis Flower” (“Flower Song” in Bizet)—the music expresses the character’s passion for the woman who has

Carmen (Dorothy Dandridge) sings “Dat’s Love” (“Habañera”) in a realistic setting, the cafeteria of a parachute factory, in Carmen Jones.

already seduced and abandoned him—is also too becalmed, another instance of the filmmaker seeming to resist the lure of Bizet’s music. Working on a chain gang, Joe, shirtless, performs the number against a panoramic mountain vista that could have been imported from River of No Return. But the implied connection between the deep sexual longing conveyed in the song and the spectacular setting is obscure. Filmed in one unbroken take, the number has a static quality reinforced by Harry Belafonte’s febrile performance—there isn’t enough going on in his face and body to hold the audience’s interest for the duration of the shot.

In “My Joe” (“Micaela’s Air” in Bizet), as Cindy Lou searches for Joe in empty locales (a boxing club, a rickety stairway, a grim city street) that foreshadow her bereavement, the correlation between song and setting is far more potent. This time, treating the aria (magnificently sung by Olga James) as a miniature drama with a structure all its own, Preminger effectively uses intercutting for visual variety. He also stages Joe’s final aria in a dramatically charged setting, a dark basement room in which the character strangles Carmen. In the number, his face suffused with passion, Harry Belafonte, who throughout the film is too guarded for a character gripped by lust, is more expressive than at any other point.

Preminger makes some strong visual choices in opening up the story beyond the limited settings of Hammerstein’s “revue.” An unedited scene early on in a car, as Carmen goes to work on Joe, has become a celebrated early use of CinemaScope composition. Initially, the two characters are separated by a window divider, but as she moves in on her prey Carmen moves from her side of the car to Joe’s. Preminger inserts a lively action sequence in which Carmen hurls herself out of the car, jumps onto the top of a moving train, and then leaps off the train onto a hillside—a cinematic way of representing the character’s impulsive physicality When Carmen returns with Joe to her family house in a small black community overrun with hanging moss and sweltering with humidity, the atmosphere oozes sex, and Carmen, grinding her body against Joe’s, slowly takes off his belt. (Was Joe Breen looking the other way?) A boxing ring scene (shot in Olympic Stadium in downtown Los Angeles) explodes with a pent-up violence that reflects Joe’s growing rage.

“For a whole generation of blacks, Carmen Jones was the film,” historian Donald Bogle recalled.

It is still an important film, as is Dandridge’s performance. It is still one of the great black films. For many blacks, the film and Dorothy remain alive, passed on from one generation to another, without the larger white culture acknowledging it. What makes it so compelling to audiences still—and surely Preminger understood this—is that it is a film in which an African-American woman is not only at the center, but she is making her own choices and is in control, unlike the way Hollywood had previously depicted black women, as in Cabin in the Sky and Pinky. Carmen lives in a world where men are calling the shots, and yet she matches them. And there is an intimacy between Dandridge and Belafonte that was new for black audiences. Their romantic scenes still have a contemporary kick and edge.40

In the weeks before the world premiere of Carmen Jones, Otto personally attended to every detail of advertising and promotion and monitored Dorothy’s extensive publicity campaign. At the same time he was in rehearsal in New York for a television special to be presented live and in color on NBC on October 18, only ten days before the world premiere of his second independent film. For two intense weeks, Otto commuted daily from Manhattan to the Kaufman Studios in Queens to rehearse Tonite at 8:30, a trio of one-acts (“Red Peppers,” “Still Life,” and “Fumed Oak”) by Noël Coward. Early on, it was apparent that he was in trouble. “He didn’t know anything about live television,” recalled actor Larkin Ford (then known as Wil West), who had had extensive experience in the then new medium. “We all felt Otto looked down at the medium, and he made the mistake of trying to transfer film technique to what we were doing. He set camera and lights as for a movie, and he was so concerned about the camera—he didn’t seem to be aware that he’d be in front of a monitor pushing buttons—that there was no time for us actors.”

The stellar company included Trevor Howard, Gig Young, Ilka Chase (with whom, years before, Otto had had a fling), and Gloria Vanderbilt, but the only performer Preminger seemed to pay any heed to was Ginger Rogers. “Ginger was the star and she was very nervous about the show,” as Ford recalled. “She knew she needed direction and she demanded it. Otto did work closely with her, and she really listened to him. For the rest of us, he’d bark directions from a distance. His approach was so different from that of Arthur Penn, with whom I had worked on live television. Penn knew a lot about acting and understood actors and he would get up very close to each of us.”41

At the beginning of the third week of rehearsals, as Preminger continued to be preoccupied with technical details (and, no doubt, with Dorothy and Carmen Jones), there had still been no complete run-through. “He had no sense of what was needed to play this kind of material. Otto didn’t ‘get’ Noël Coward,” Larkin Ford felt.

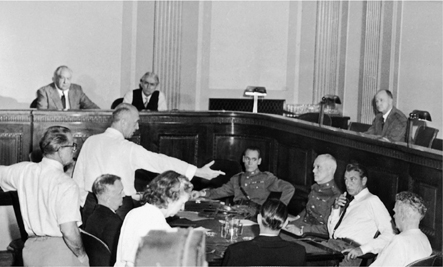

Rehearsing Ginger Rogers and Gig Young in Tonite at 8:30 for NBC, the directors misbegotten foray into live television.

As tensions began to build, I became the chosen one on the set. Whatever I did, he grumbled. I don’t think he had cast me just to humiliate me, but I was miscast and he was responsible for miscasting me. Gig Young was miscast too, but Gig couldn’t have cared less; he just sailed through and said the pay was good. Trevor Howard, who thought Otto’s direction was nothing, was bored, and tiny Gloria Vanderbilt just smiled all the time. Otto called himself a liberal, but a true liberal doesn’t treat people the way he did; I have a feeling he would have voted for George Bush.42

With a live performance in less than a week and three essentially undirected playlets in shambles, something had to give. Something did. On October 15, three days before the show was scheduled to air, NBC producer Fred Coe walked onto the set to talk to Preminger. The next day, Otto wasn’t there, and Coe, noted for his diplomacy, announced that “ ‘Mr. Preminger will not be with us. I will be with you through the presentation.’

Otto was never seen again,” Ford said. “He had been fired offstage. We did feel sorry for him, a man of that stature to be summarily dismissed for incompetence. But he was incompetent. Otto had great confidence in himself and it must have been disturbing to him when he discovered that he hadn’t been prepared.”43 When the show aired, however, Otto Preminger received credit as producer and director, and in taped segments, shifty-eyed and noticeably ill at ease, he introduced each of the one-acts. Tonite at 8:30 is a classic example of primitive early television. The sets are wobbly; the actors’ timing is always a beat or two off; the pacing is sluggish. Technical glitches—a microphone covers Gig Young’s face for a moment; a door sticks on one of Ginger Rogers’s exits—add to the blurred focus. In later years Preminger would appear regularly as a talk show guest, but he never again directed for television.

The reception of Carmen Jones at the end of the month, however, more than compensated for Otto’s disappointing television debut. He was elated by Dorothy’s reviews and basked in his role as a star maker. On February 12, 1955, as Preminger had assured her she would be, Dorothy was nominated as best actress by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the first black woman ever to be recognized in this category. Otto repeatedly cautioned Dorothy, however, that Hollywood was not ready to give her the best actress Oscar and that there was no chance she would be making a triumphant walk to the stage of the Pantages Theatre on Oscar night. And indeed, when the awards were handed out on March 30, the best actress Oscar was given to Grace Kelly for The Country Girl. (Not until nearly forty years later, when Halle Berry was honored for Monster’s Ball, would a black woman win a best actress Oscar.)

As she continued a punishing schedule of public and nightclub appearances, Dorothy signed a contract with Darryl Zanuck to make one picture a year for a three-year period. Despite his own hectic schedule, Preminger began to direct Dorothy’s cabaret act. In ironic contrast to how he had presented her in Carmen Jones, Otto desexualized Dorothy’s nightclub performance. As Earl Mills observed, “Dorothy thought of herself as a patrician lady of elegance and wanted to be a lady, a nun, onstage.”44 Otto bought her a black, loose-fitting, floor-length gown and worked with her in selecting a less jazz-based repertoire. But like live television, the nightclub was not Preminger’s métier, and when Dorothy opened her Preminger-inspired act at a Miami Beach hotel, it was, according to Earl Mills, “an abysmal failure. She soon went back to the old Dorothy Dandridge. Otto’s hand was constantly in evidence in her professional life. Had he been just her lover it would have been better but he wanted to control every facet of her life.”45

Although she would sometimes complain when Otto would arrive, unannounced, at one of her openings—his take-charge personality could enflame her anxiety—by and large she was a compliant pupil. Otto represented a cultivated world she longed to be part of. He taught her about art and literature as well as about fine furniture and fine dining. He helped her to buy a new home (which, he said, befit her new status as an international star) and to furnish it in exquisite taste. And at this point, Dorothy hoped that being the dutiful Galatea to Preminger’s bombastic Pygmalion would lead to marriage.

In late February Dorothy and her director attended the film’s premieres in London and Berlin (in both cities the film would play for more than a year in exclusive first-run engagements). There was no Paris opening, however, because a technicality in French copyright laws prevented the film from being shown in France. Nonetheless, in an out-of-competition screening Carmen Jones was selected to open the Cannes Film Festival in May. To be present, Dorothy had to negotiate for a week’s leave of absence from her engagement at the Empire Room of the Waldorf-Astoria in New York. On May 7, she and Otto departed for France, where on their arrival at the Nice airport they were met by a cordon of international journalists and photographers. They posed for pictures for over an hour before they were ushered through the throngs to a long, cream-colored Cadillac, in which they were driven to the Carlton Hotel in Cannes. The night of the screening, dressed in a white gown and white fur stole, Dorothy arrived on the arm of her director. Gallantly, Preminger moved aside to allow his star to face the flashbulbs on her own. She struck the pose of a haughty, radiant diva who looked as if she had conquered the world; and that night, when the film was received with a thunderous ovation, she had. Perhaps because they were in a foreign country, and perhaps feeling protected by the fact that they were honored guests of the world’s most prestigious film festival, the director and his star were seen together in public throughout their brief stay. Not only on official occasions but also at private luncheons and dinners and for drinks on the Carlton terrace, they were an item: Otto and Dorothy. And anyone with eyes could have spotted the fact that they were crazy about each other. More than gratitude was contained in the star’s rapt gaze at her director.

For Preminger, the international acclaim at Cannes was the beginning of an illustrious decade at the top of the Hollywood hierarchy. For Dorothy, however, it was the beginning of the end. Soon after returning from Cannes, Dorothy agreed to appear in a supporting role as an Asian in the film of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical play The King and I. Otto, however, urged her to turn down the offer, assuring Dorothy that if she accepted the role she would be relegated ever after to the category of a supporting player.

Preminger directing Gary Cooper in The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell, the only dull court-room drama in the filmmakers career.

Acting on her mentor’s advice, she withdrew. “Preminger, usually adroitly pragmatic and perceptive, was in this instance blind to movieland realities,” as Donald Bogle pointed out.46 And as Dorothy herself was to reflect, “My decline may have dated from that decision. Otto was sincere. He had never believed in playing bit parts as an actor himself, and he passed on his convictions to me. Though he was honest, his advice could have been in some part my undoing. I would have received seventy-five thousand dollars for playing Tuptim, and I would have been in a picture seen by millions. [And] it would not have been the role of a Negro.”47 (Rita Moreno, also non-Asian, got the part.)

At the time that he was immersed in supervising Dorothy’s life and career and had already begun planning his next independent project, The Man with the Golden Arm, Preminger accepted an assignment from producer Milton Sperling to direct The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell. Otto admired the defiant protagonist, Brigadier General Billy Mitchell, assistant chief of the Army Air Service, who provoked his own court-martial in the 1920s in order to expose the indifference of his military commanders to developing a strong air force. And he was enticed by the fact that the film’s lengthy third act is set in his favorite dramatic location, a courtroom. It’s possible to see why Preminger was tempted by the material, as well as by the chance to work with the film’s star, Gary Cooper. But he should have passed.

Otto didn’t like the original script, by Emmet Lavery (whose play The First Legion had been his farewell production in Vienna), and at his insistence Milton Sperling hired the speedy Ben Hecht, who in less than a week rewrote to Preminger’s specifications. (When the film received an Academy Award nomination for best screenplay, Emmet Lavery and Milton Sperling were credited as the cowriters.) Throughout the shooting, which took place in the summer of 1955 from June 18 to August 13, Otto fulminated against Sperling’s indecisiveness. But he enjoyed working with Gary Cooper, always courteous, reliable, and understated. Sandy Gardner, frequently on the set, recalled that Otto was “very gentle with Cooper, and very solicitous about the star’s lighting and makeup. Cooper was playing a character who was younger than himself, and I saw Otto change the lighting so Gary’s dewlaps would not be visible.”48

Preminger and Cooper, however, made the curious choice of turning Billy Mitchell, a firebrand, into a weary figure who seems to embrace defeat. The night before he is to testify, the character is ill with malaria and the next day in the courtroom he seems physically as well as intellectually depleted. Preminger reinforces the downbeat atmosphere by pinning the haunted-looking Cooper against a brick wall in isolating one-shots. The most energetic character is Mitchell’s nemesis, the chief prosecuting attorney, played by Rod Steiger with a full cut of ham, the kind Preminger usually trimmed to the bone. Although the film’s strangely icy, dispirited portrait of a mutinous character typifies Preminger’s resistance to conventional Hollywood heroism, the script isn’t strong enough to support a revisionist approach.