For his first three independent projects, Preminger tackled controversial material. For his fourth, he went out on a different kind of limb.

At the top of an application form distributed to theaters, drama schools, high schools, and colleges in the spring of 1956 appeared the following statement:

Otto Preminger (producer-director of Laura, The Moon Is Blue, Carmen Jones, The Man with the Golden Arm) is convinced that there is somewhere in the world an unknown young actress who can be an exciting Joan of Arc. By means of a competition conducted with the cooperation of motion picture theatres throughout the world, he intends to find a young actress who will play this role. Mr. Preminger will visit 15 cities, starting in September [1956], to audition selected candidates who have fulfilled the requirements listed below. For these auditions, contestants must be prepared to play Scene I of [George Bernard] Shaw’s Saint Joan and Scene VI, the latter starting with Joan’s speech, “Perpetual imprisonment! Am I not then to be set free?” The most promising candidates will be selected for screen tests, and the 5 best tests will be shown on a national television show. Mr. Preminger will select the winner and cast her in Saint Joan.

The statement concluded with a warning: “Mr. Preminger’s decisions shall be final.”

Four requirements were listed. The candidates had to be between the ages of sixteen and twenty-two; had to have a complete command of the English language; had to submit a photo; and had to complete the entry blank “shown below” and mail it before midnight August 23, 1956, to Otto Preminger, Hollywood 51, California. At the bottom of the entry blank the contestant was asked to check which city “[she] can most conveniently reach for an audition if selected: Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Los Angeles, Montreal, New York, St. Louis, San Francisco, Seattle, Toronto, Washington.” Preminger, appearing in a trailer shown in theaters throughout the United States and Canada, explained the terms of the search. “I have no specific image or character in mind,” he stated. “I only know there are certain qualities necessary to portray this part: a great deal of sincerity, honesty, an almost fanatic devotion, and naturally, also talent.”1

It may have had the trappings of a show business hustle (“My worldwide search met with equally worldwide skepticism,” Otto noted wryly),2 but his quest was genuine. He had not already cast the role, and no secret favorites were waiting in the wings. Preminger’s search—the filmmaker was hoping it would become as celebrated as David O. Selznick’s for an actress to play Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind— also expressed his belief that Joan, only seventeen when she was burned at the stake, should be enacted by a fresh unknown of approximately the same age. “In the theater the audience accepts an older actress in the role,” he said, noting that the part was “originally played by Sybil Thorndike when she was forty-one.” “The greatest stage actresses, however, developed a certain style and nothing that is very stylized has ever succeeded in movies. The movies are looking for a ‘being.’ The camera is more discerning, it comes closer and so we have to be more authentic. Also the film going public is less sophisticated. They don’t forgive.”3

He didn’t realize it at the time, and no one told him, but Preminger’s plan contained a probably fatal flaw. Whereas many naturally talented, unknown seventeen-year-olds could play a seventeen-year-old as conceived by Hollywood screenwriters, how many could persuasively embody the exceptional teenager Shaw had written, a young woman of extraordinary, perhaps even supernatural, gifts? Communing with the voices of Michael and Margaret that come to her through the bells in the church of her native Domrémy, this divinely inspired teenager possessed powers that would alter the course of history. Moreover, the illiterate young woman is both a poet

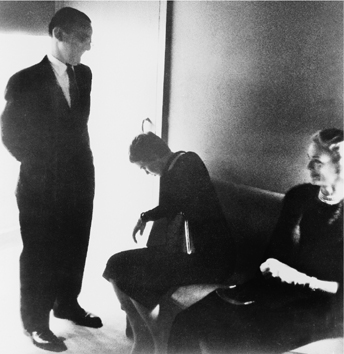

With a group of unknown young women hoping to play Saint Joan, in September 1956.

and dialectician who speaks in the long, rolling sentences of a Shavian orator. Surely the odds of finding, anywhere in the world, an inexperienced, unprofessional teenager blessed with the technical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual capacity to portray Shaw’s great heroine—one of the most demanding roles in world theater—were close to zero. Probably only a miracle, of the kind that the messianic heroine herself would be capable of, could have delivered such a person.

But in the spring and summer of 1956, as he began to publicize his search for Joan, Otto was optimistic. And so were the over 18,000 applicants who mailed in their entry forms by the August 23 deadline. Preminger and his staff narrowed the field to around three thousand young women, each of whom the producer was planning personally to audition on a thirty-seven-day tour budgeted at $150,000, during which he would fly over 30,000 miles visiting nineteen cities in the United States, Canada, and Europe. His marathon began in London at the end of August.

Before he held the first of 250 auditions scheduled in London, where the film was to be shot starting in January 1957, Preminger set up an office at 144 Piccadilly in a suite in a mansion that belonged to producer Alexander Korda. To head his London base of operations Otto hired an Englishwoman, Rita Moriarty who had worked in New York for the producer Alexander Cohen. “I specialize in difficult people,” Moriarty recalled. “I’m interested in them to see if I can handle them. I had been warned that Preminger was dreadful to work for—he really had a terrible reputation. When I met him—he was at the Dorchester Hotel in Cecil Beaton’s suite—I liked him without being mad about him. We got along well but not that wonderfully well. I had to fight for my salary. But I knew I was valuable to him because he needed a British anchor in his office, and since I had worked in England and Otto hadn’t I had the upper hand.” As Moriarty began to help Preminger hire his crew, she tried to point out that his criteria were wrong. “Foolishly, Otto was impressed by people who had the right address and who knew the Queen. But that’s not what you need for a crew. You need cockneys who work hard. He hired too many effete ones. Otto wasn’t knowledgeable about the British, but I also saw that it was larger than that: he just didn’t understand people. He was interested in them, but he didn’t understand them.”4

During the London auditions, held in the ballroom of a great house on Park Lane, Rita Moriarty sat on one side of Preminger while on the other was Lionel Larner, his twenty-two-year-old London casting director who pre-interviewed all the candidates. As Larner recalled, “The auditioners were to read a single speech, ‘Give me that writing.’ One girl came in and said, ‘I’m not going to read because I am going to play Saint Joan, my voices told me.’ ‘You misunderstood your voices,’ Preminger answered.” After London, Larner traveled with Preminger to coordinate auditions in Edinburgh; their bond strengthened when Larner made Otto laugh. “ ‘You are the only member of my crew who is not married,’ Otto said to me. ‘Will you let me pick a wife for you? After all, I am the man who is going to select Saint Joan.’ ‘Let me see her performance first,’ I said. He was tickled. Otto loved wit.”5

After Edinburgh Preminger held auditions in Manchester, Dublin, Glasgow, Copenhagen, and Stockholm. Returning to America, he auditioned 268 candidates in New York. By the time he reached Los Angeles, he realized that there were far fewer potential Joans than he had expected. “I thought I could find at least 50. But I won’t test that many. I began to realize if looking for an unknown were so easy, a star would be easier to find.”6

For the American auditions Sandy Gardner accompanied Preminger. “It was exhausting, and very fast,” Sandy recalled. “Some of the ones Otto looked at had sent in nude shots in which they were spread out on leopard skins. They didn’t understand the nature of the part. The girls were given a single long speech and it was my job to escort each girl into the ballroom of a hotel, where the auditions were usually held. The girls would get a cue from me when to begin.”7

Midway through his American tour, at the Sherman Hotel in Chicago on September 15, 1956, Preminger thought he might have found his Joan. “Something clicked,” he recalled, when Jean Seberg, a seventeen-year-old from Marshalltown, Iowa, entered the audition room. (Like all the others, Jean’s interview was filmed.) When an off-screen Preminger asked, “Do you want to be an actress?” Jean, with an affecting clarity and directness, answered: “Very badly.” “Why haven’t you worn a cross?” Preminger inquired. “My family is too poor to afford one,” Jean replied, bowing her head. But after Preminger responded with a doubtful “Really?” she giggled. “Because I knew all the other girls would be wearing them,” she admitted. Surprised by her statement, Preminger laughed.8 When Jean performed the audition scene, he was impressed by her delivery, free of the theatrical curlicues he had no patience for. The young woman’s charm and sincerity touched him, and he liked her smile, her all-American vigor, and the confident way she carried herself. He was certain Jean would be among the finalists he would test in New York in mid-October.

“I saw Jean’s audition in Chicago,” Sandy said. “Up to that point, Otto had really been impressed by only one other actress, Kelli Blaine, whom we had seen earlier in New York. Kelli was tough, with a gap between her front teeth like David Letterman. She was not beautiful, but she looked the part: she was right for the part. Still, in Chicago, I put my vote in for Jean, who was damn good too. But Otto didn’t think my opinion was worth much.”9

Preminger called Jean’s startled parents to ask them to allow their daughter to come to New York two weeks before the scheduled screen test so that he could work with her. At his first meeting with Jean at the Ambassador Hotel in New York, Otto started to worry. Had someone been coaching his discovery? She no longer seemed to be as spontaneous as she had been in Chicago. Disappointed, he began to bark at the frightened novice. “His anger bore a double edge,” as Jean’s biographer, David Richards, observed. “On the one hand, he genuinely appreciated her untutored freshness, a quality he was determined to preserve on film, and he was distressed to see it endangered. On the other hand, his ego was at stake. The actress he chose for Saint Joan would be his creation, and his alone. Meddling would be forbidden.”10 Preminger’s evident disapproval stung Jean, who was certain she no longer had any chance of getting the role.

Jean Seberg waiting with a production assistant and an unidentified woman to hear if she has been chosen to play Saint Joan.

After auditioning over three thousand candidates, Otto in the end made only three screen tests: Jean’s, Kelli Blaine’s, and one of a woman from Stockholm, Doreen Denning. For the test he asked Jean if she’d be willing to have her long hair cut short—a sign that despite his disappointment in her during rehearsals she remained the front-runner. Jean, of course, complied. The androgynous short haircut highlighted her fine bone structure, her clear, sensitive eyes, and a tremulous sex appeal waiting to be released. As he prepared Jean for the test, Preminger’s temper flared as he asked her to repeat scenes many times until he got exactly the gestures and intonations he wanted. “What’s the matter? Don’t you have the guts to go on?” he yelled when he had driven Jean to the breaking point. “I’ll rehearse until you drop dead,” Jean answered.11 He was testing her limits, a usual Preminger strategy, and he was impressed by the young woman’s stamina. “Kelli Blaine was even stronger than Jean,” Otto’s stepson observed, “but I think Otto chose Jean because in the end he felt he could manipulate her more easily”12

On Friday, October 19, Otto informed Jean Seberg that she was his Saint Joan. Two days later Preminger, in his most expansive, master showman style and beaming like a new father, introduced his discovery to the press corps he had summoned at noon to the executive suite of the United Artists offices in New York. That night, he presented his choice on The Ed Sullivan Show, where, before an estimated sixty million viewers, Jean reenacted her audition scene. Her beauty, her charm, her vivacity could not disguise the irreducible fact that Jean Seberg was an amateur. Indeed, in her entry form she had listed as her entire résumé “many local plays and winner at the State University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, for an exerpt [sic] from Shaw’s Saint Joan.” (Attached to Jean’s application had been a letter of support from a local booster, J. W. Fisher, president of the Fisher Governor Company, manufacturers of gas regulators, diaphragm control valves, liquid level controllers, and pump governors. “A young lady of our community … is within the age requirements, having graduated from High School. This summer she is playing summer stock at Cape May, New Jersey. She is blonde, and most attractive. Her voice carries the proper authority and she has talent.”)13

A few days after her appearance on Ed Sullivan, Jean was taken by limousine to Boston, where she underwent a secret operation to remove moles from her face and throat. Returning to Marshalltown, she was greeted with a welcome befitting a world leader. She remained at home until November 13, her eighteenth birthday, when she left Marshalltown to begin her journey to London. On her arrival Preminger sequestered her in a suite at the Dorchester Hotel, where he hoped, in a few short weeks, to transform Jean of Iowa into Joan of Arc. In preparation for the first read-through with the entire cast, scheduled for December 14, Preminger arranged for Jean to be given elocution lessons designed to transform her flat Midwestern twang into a more refined mid-Atlantic diction and to be tutored in French (which, as preparation for performing Shaw, seemed rather beside the point). In nearby Rotten Row Jean was taught how to ride a horse, to wear armor, and to draw a sword.

While Jean was studying, Preminger lined up the rest of his cast. (The only actor he had signed before Jean was Richard Widmark, who was to play the Dauphin.) Lionel Larner “rushed around seeing all the plays. I kept files and lists and then brought in the cream of the London theater to see Otto,” Larner recalled.

He had an idea that English actors would play the English characters, and Irish actors would play French characters. The actors would come to see him dressed in Turnball and Asser shirts, and Otto thought they were all gay. “You don’t understand, Mr. Preminger, they have to be properly dressed at the Dorchester,” I told him. I began to ask actors to “look ordinary.” Preminger would say to important actors, “You’re not right,” and I told him he couldn’t dismiss them like that, he had to spend more time with each of them.

Preminger “wanted to go with strength,” Larner said, “but he didn’t seem to realize that Jean would be dwarfed by playing opposite British knights like John Gielgud. We all felt that she wouldn’t be able to stand up to the top-drawer actors he was signing up. When he showed me Jean’s Chicago audition and asked my opinion, I told him Jean’s American accent seemed wrong, but I quickly added, ‘I have to bow my head to your superior knowledge of these things.’ ”

Larner saw Jean regularly as she was preparing for the first read-through with the cast. “Jean grew up very fast. When she first came over, she wore a shapeless dress, then there was an amazing transformation. With her hair cut and her moles removed, she was incandescently beautiful, and she became an instant celebrity. And when she appeared for the press in a black Givenchy dress, no one else in the world looked like her. Otto bought her jewelry and took her dining with the Oliviers. Her ego was such that she thought the Oliviers were dining with her.” Inevitably there were rumors that Preminger was romantically involved with his discovery. “Nonsense,” Larner said. “She was a schoolgirl to him. He liked young people—and he really believed in giving young people a break. He wanted to use the newest, freshest actor, and he believed in Jean’s freshness. There was no affair: period.”14

On the first read-through, held at Alexander Korda’s office, Preminger had a set-to with Paul Scofield, cast as Brother Martin. Scofield walked out. With Larner’s assistance Preminger quickly replaced him with Kenneth Haigh, who had been acclaimed for his recent performance in Look Back in Anger. After the fracas with Scofield, the three-week rehearsal period that followed was, for Preminger, the most pleasurable part of the project. He was thrilled to be working on one of the great plays he had memorized in his youth.

The script that he and his cast were reading, however, was an edited version of Shaw’s long play which had a running time of three hours. After over two years of negotiating with Shaw’s estate, Otto and his scenarist Graham Greene had been given an extraordinary concession: they could change up to 25 percent of Shaw’s dialogue. In the event they altered only 5 percent, but to reduce the play to a manageable 110 minutes they had had to make cuts and changes. They had trimmed lengthy set speeches, removed much of Shaw’s political discourse, expanded the action to include a coronation scene and preparations for battle, and decided to open the film with a portion of Shaw’s epilogue. Purists and die-hard Shavians, as Otto was aware, would cry foul, but for the filmmaker, and never more so than in the three-week read-through with his cast, the play remained the thing. Despite the changes he and Greene had made, it was Preminger’s intention to honor, not to mutilate, the work of a playwright he revered.

While Otto was in London with his cast, at Shepperton Studios twenty full sets were being constructed. When the sets were ready after December 20, Preminger relocated the company to Shepperton for full-dress rehearsals. On January 8, 1957, at 8:30 a.m., he began shooting. In addition to the camera that was shooting Saint Joan, a second unit was on the spot filming a short promotional, “The Making of a Movie.” The international press corps Preminger had assembled watched the double filming.

Recorded for the promotional film, Jean’s first take of the scene in which Joan, encased in armor, makes her entrance at the Dauphin’s court, reveals her terror. Jean doesn’t seem to have any point of view about her character; her voice is constricted with tension; her gestures are tentative and inescapably contemporary. Poor Jean Seberg looks as if she would rather be in Marshalltown than where she was, on exhibit before the critical, expectant gaze of the international press and two cameras. Under the circumstances that Preminger had set up with an almost perverse disregard for the well-being of his young discovery, how could Jean have felt other than crushed? “It’s my belief that Otto wanted Jean to feel and actually to be overwhelmed,” Lionel Larner observed. “That was how he saw the part: that Joan was enclosed by representatives of the powerful institutions of church and state. That was why he cast powerful actors opposite her: it conformed to his idea of a birdlike Joan of Arc. Of course such an interpretation could not work out.”15

Preminger could not and would not admit it, but he must have sensed from the start that Jean was out of her league. A director with a different temperament might have admitted he had made a mistake and replaced Jean with a more experienced performer. But Otto was not capable of such a course of action, and besides he still believed in Jean and was convinced that, despite the odds, he could force his vision of the character onto her. For his sake, to vindicate his choice of her and to justify the hullabaloo he had created in his worldwide search, Jean Seberg had to succeed. As Rita Moriarty claimed, “Otto was conceited enough to think he could extract a

Preminger rehearses the trial scene in Saint Joan with Felix Aylmer, Anton Walbrook, Jean Seberg, and Kenneth Haigh.

performance from her.”16 To the increasing dismay of onlookers, however, he seemed incapable of creating an environment in which Jean might be able to flourish.

As he became more frustrated, Otto would frequently demonstrate how he wanted Jean to play a scene. In “The Making of a Movie,” there’s an eerie moment when Otto enacts, with precisely the kind of theatrical artifice his casting of Jean was meant to defy, how he wants the character to crack up at the end of a tense scene. “If Jean didn’t get it right away, he would give her traffic directions, ‘Go from here to there, and keep in line with the camera,’ ” Rita Moriarty recalled.17 Larner observed that in the cathedral scene, when Preminger couldn’t get Jean to cry, he bellowed, “You are ruining my picture!”18 “You’re not thinking the part!” was a line he often uttered in one of his rants. But he didn’t seem to realize that his mistreatment was preventing Jean from doing any thinking at all. “What she was supposed to be thinking was increasingly mysterious to her,” as David Richards noted. “Forced to repeat some takes ten or twenty times, she felt the spontaneity draining from her. Her face froze and her body stiffened.”19 As Richards commented, Preminger “had not discovered an actress; he had engaged a puppet. If the character was distraught, Jean could be rendered distraught.”20

Cast and crew were all sympathetic to Jean. “You couldn’t not like her,” Kenneth Haigh said, surely speaking for all.21 Nonetheless, though some of the most respected actors in the British theater of the time witnessed Preminger’s mishandling of Jean, no one, not even John Gielgud, who had great sympathy for her, had the nerve to stand up to the director. “Having chosen her but then decided it was a mistake, Preminger was utterly horrible to her on the set,” Gielgud observed. “She didn’t know anything about phrasing or pacing or climax—all the things the part needed—but she was desperately eager to learn and also desperately insecure about everything.” When Gielgud at the end of shooting presented Jean with a cup and saucer that had belonged to his great-aunt, the legendary actress Ellen Terry, Jean “simply broke down in tears,” Gielgud recalled.22

Despite the circumstances, Jean Seberg never cracked on the set. “Otto had cast her because of a strength he had seen in her, and during the filming he could not break her,” Lionel Larner said.23 Rita Moriarty agreed. “The steel that got her the part prevented her from crying. She was a tough cookie, and I must say I was impressed by Jean’s self-control. That was what Otto had liked about her at first, and I believe it’s that quality that through it all held his respect for her. Otto admired those who would not fall apart when he yelled. Jean was firm, stoic, and she would not let him get her down.”24 Away from the set, though, Jean’s stalwart façade crumbled, according to production photographer Bob Willoughby, who befriended her. “Often at the end of the day’s shooting, she would be sobbing hysterically. Jean would be broken.”25

His outbursts unsettled everyone except Otto, who recovered from his tirades in a matter of seconds, ready to carry on as if nothing had happened. He may have had hourly tantrums, but as the shooting progressed he was not displeased. His master cinematographer, Georges Périnal, and Roger Furse, his equally accomplished set designer, were giving him what he had asked for. His classically trained company was performing in a style adjusted to films rather than the stage. And he saw in the rushes plentiful evidence of Jean’s naturalness and strength—the qualities for which he had hired her. “The dailies looked excellent,” he recalled.26

Preminger’s intemperance with Jean did not mean he disliked her; quite the contrary. As much as everyone else, he cared for her personally, and he never ceased feeling responsible for her. He gave her lavish presents, and many times after hours at the Dorchester he reverted to a calm, fatherly demeanor. On one drive back to the hotel from Shepperton, about midway through shooting, he informed her that he was going to cast her in the leading role in his next film, Bonjour Tristesse, an adaptation of Françoise Sagan’s recent best-selling novel about la dolce vita on the French Riviera. Jean’s “gratitude was immense,” as David Richards reported.27

Near the end of shooting, Jean was involved in a near catastrophe that epitomized how she felt about working with Preminger. “I’m burning!” Jean screamed as smoke and flames from two of seven gas cylinders enveloped her during the filming of the Maid being burned at the stake. Lining up the shot on a crane high overhead, Preminger was horrified as crew members quickly released Jean from her chains while studio firemen poured water onto the flames. Singed but unhurt, Jean offered to redo the shot but Otto sent her back to the Dorchester in a limousine and arranged for a doctor and nurse to be on hand. Jean never remounted the pyre. Although Preminger was accused, preposterously, of having arranged the mishap as a publicity gimmick, after it had occurred he certainly didn’t block newspapers and magazines from reporting the incident. A journalist and photographer from Life had been on the set, and Otto was pleased when the event was given a big spread in the magazine. “We got it all on film. The camera took 400 extra feet. The crowd reaction was fantastic. I’ll probably use some of it,” Preminger boasted, seemingly unaware of how callous he sounded.28

Jean’s last day at Shepperton was March 15. Soon after, weary yet relieved, Jean returned to Marshalltown, which had never looked smaller or more provincial to her. She knew at once she could never again live at “home” and realized as well that the kind of conventional lives her high school friends were pursuing would never be available to her. Is it possible that during her monthlong stay in Marshalltown it occurred to Jean (and to her family as well) that having been chosen by Otto Preminger might not have been the luckiest moment of her life?

In mid-April Otto called her to New York for publicity. At the beginning of May he brought her to Paris, where, on May 12, as the crowning touch to the drumroll of publicity that had enveloped the project first to last, Preminger presented the world premiere of his film at the Paris Opéra.

The unrivaled splendor of the Palais Garnier and the assemblage of celebrities from show business, politics, fashion, and international business who paid a thousand dollars a seat to benefit the Polio Foundation transformed the premiere of Saint Joan into an event that surpassed any Hollywood opening. Appearing on the arm of her director, Jean was radiant in an aqua Givenchy evening dress that Preminger had presented to her as a gift. Although test screenings of the film in New York in April had evoked tepid reactions and tonight she would be facing the judgment of an international

tribunal, for the furiously clicking cameras Jean projected the poise of an acclaimed star. On this gala occasion she looked far less like Saint Joan than like a cosmopolitan young woman who embodied a new style, Gallic chic garnished with an all-American twist.

The applause at the end of the screening was lukewarm. But at the reception at Maxim’s later in the evening, Preminger, with a resplendent smile, personally greeted every single guest and behaved as if the premiere had been a triumph. The French critics, by and large, dismissed the film as a betrayal of a national heroine, and business on the Champs-Élysées was lackluster. Although he realized that the film would be likely to receive the same cool reception when it opened in America at the end of June, he proceeded to promote it with flair. He booked Jean on a grueling twenty-seven-day tour that included press conferences, photo sessions, radio and television interviews, and appearances at special promotions. The star of Saint Joan appeared frequently at downtown department stores and greeted the public on the steps of numerous city halls. Just before the American premiere, however, Preminger whisked Jean to London for the opening at the Odeon Leicester Square. The British reaction was also dispiriting, with critics complaining that Preminger and Graham Greene had not been sufficiently reverential toward Shaw.

From London Otto sent Jean to recuperate on the French Riviera and to begin to prepare for Bonjour Tristesse. When Saint Joan had its American premiere at the Orpheum Theater in her hometown on June 24, Jean was in Nice studying French, swimming, lingering over coffee in outdoor cafés, and acquiring a French boyfriend. Distracted by the easy life, and with the burdens of her instant celebrity lifted, Jean was all but immunized against the American reviews, which ranged from barely respectful to scorching. “Too often Jean Seberg looks as though she’d be more comfortable on a soda fountain stool,” Paul Beckley huffed in the New York Herald Tribune on June 27. “Skimpy,” “sketchy,” “not well-articulated,” and “a series of dissertations on an important theme” were typical complaints, though many reviews acknowledged that both the director and his star took command during the climactic trial sequence. Business was dismal, and after its first-run engagements—Preminger himself booked the film on a then-thriving art-house circuit; in Los Angeles, he opened Saint Joan at the Four Star, the upscale venue where The Moon Is Blue had premiered—the film never received a wide general release. A year after it opened, the worldwide grosses were less than $400,000, making Saint Joan Preminger’s first financial failure as an independent filmmaker. “What good are successes if you can’t have a failure once in a while?” he quipped, affecting a cavalier indifference he could not truly have felt.29 Preminger’s attempt to promote Saint Joan with the kind of showmanship befitting a Hollywood blockbuster seems, in retrospect, strangely but also endearingly naive, the most touching merger of idealism and commerce in the filmmaker’s career. How could he ever have imagined that his reasonably faithful adaptation of a dense, talky Shavian masterwork could ever have achieved popular acceptance?

Both at the time and ever after, Preminger defended Jean. “I think this girl has great talent, great poise,” he said in an interview in the New York Times on January 12, 1958, “and it would be unfair to blame her for the picture. Maybe it was just as much my fault. Maybe it was an error to try to make a movie out of Shaw.” “I made the mistake of taking a young, inexperienced girl and wanted her to be Saint Joan, which, of course, she wasn’t,” he told Jean’s biographer. “I didn’t help her to understand and act the part. Indeed, I deliberately prevented her, because I was determined that she should be completely unspoiled. I think the instinct was right, but now I would work with her for perhaps two years until she understood the part right through. Well, that was a big mistake, and I have nobody to blame but myself”30 In his autobiography, Preminger offered his final assessment: “Many people blamed Jean Seberg and her inexperience [for the failure of the film]. That is unfair. I alone am to blame.”31

Some of Preminger’s comments about Saint Joan after the fact revealed it wasn’t only Jean Seberg who had been overmatched by George Bernard Shaw. “I misunderstood something fundamental about Shaw’s play” Preminger said. “It is not a dramatization of the legend of Joan of Arc which is filled with emotion and religious passion. It is a deep but cool intellectual examination of the role religion plays in the history of man.”32 Saint Joan, to be sure, is a play of ideas, but it is not, as Preminger claimed, a “cool intellectual” exercise stripped of emotion. To the contrary, if it is interpreted properly—that is, according to the playwright’s intentions—turbulent emotions are released through the characters’ engagement with ideas. As Preminger didn’t fully grasp, the playwright’s great characters are great talkers for whom the play of language—discourse, debate, ratiocination—is deeply emotional, and sometimes, as it is with Joan, tinged with eroticism.

Although Preminger and Seberg were not equal to Shaw, their film does not deserve its outcast reputation. Even if the most zealous revisionist critic could not possibly rehabilitate the film as an overlooked masterpiece, it is far from being a disgrace. Enriched by Georges Périnal’s ravishing yet realistic black-and-white cinematography; Mischa Spoliansky’s distinguished score, a contemporary interpretation of medieval motifs with a plangent central theme; and Saul Bass’s elegant title sequence, in which ringing bells are transformed into a truncated torso of Joan wielding a sword, Preminger’s condensed, Reader’s Digest version of Shaw’s play is a flawed, courageous American art film of its era.

Yes, Jean Seberg lacks the technical and emotional resources to embody, in all its theatrical majesty, the variegated character Shaw conceived. Hers is an unfinished performance, a sampling. In many fundamental ways, however, she gave her director exactly the Maid he had in mind: a vulnerable figure thwarted by manipulative representatives of church and state whom she cannot understand; a religious naïf whose girlishness is graced with a budding sensuality. The qualities in Shaw’s conception that Preminger himself did not seem fully to believe in—Joan’s genius as a military leader and as a public orator, the assertiveness that enabled an illiterate teenager to alter the destiny of France—are the ones either missing or deficiently represented.

Under Preminger’s guidance, Seberg gives a performance carefully crafted for the camera rather than the proscenium. Rather than a mannish stage diva galloping through the part on her high horse trilling lines with technical bravura, Jean is a deeply feminine young woman who approaches Shaw in a fresh, unaffected way. Her Maid of Orléans, as Shaw intended, is decidedly not unsexed. When she smiles at the sympathetic Brother Martin or teases the childlike Dauphin, she is distinctly fetching—a charming warrior-saint. With lingering traces of her Midwestern roots, Jean speaks in a light, splintery voice which takes on a lyrical lilt in all the soft moments, as for instance when Joan talks of her saints who tell her what to do, or when she recalls her country home. But her voice and body language do not project the “born boss” Shaw describes in his preface. When in the early scenes she must make demands of a gruff soldier or convince the court of the truth of her voices, she lacks the authority that a genuine born boss like her director would be able to summon as if by divine right.

Preminger presents Jean cautiously. “Here is the chosen one; what do you think?” he seems to be saying to the audience as he photographs Jean primarily in neutral long takes, not for a moment trying to protect her or to amplify her work with editing, lighting, or camera movement. He presents Jean’s big scene at the end of the trial, for instance, in a single uninterrupted take. He does provide a lovely entrance for his discovery, however. In the opening scene Joan appears first in shadow, standing by the sleeping Dauphin like a spectral figure emerging from his dream. After a beat, she steps into the light.

Finally, the ordeal of Jean Seberg is an indelible part of her performance. In the conclusion of the trial sequence, in which Joan is plunged into uncertainty, first recanting and then ultimately denying her recantation, Jean, no doubt drawing on her own terror and giving everything she has to give, performs with enormous commitment, her body and voice trembling. The moment is thrilling and it is possible, after all, to see why Preminger cast Jean Seberg, and what he saw in her.

As a producer, Preminger came on like a carnival barker, bristling with bluster and braggadocio, but as a director of Shaw he proceeds in his usual subdued way. He is a scrupulous, perhaps even intimidated, Shavian caretaker who honors the word more than the image. But he is of course showman enough to provide periodic visual grace notes—brief respites from the wordplay. He offers a striking opening image of the Dauphin’s castle reflected in a lake, painterly pastoral shots of Joan on her journey to see the Dauphin, and occasional high-angle shots of Joan cowering in her cell. With Reinhardt-like authority he stages the one fully articulated action sequence in the film, the burning at the stake, shot on the largest sound stage in Europe with a cast of 1,500 screaming, pummeling witnesses seized by an almost sexual frenzy at the prospect of Joan’s imminent death. His handling of the coronation and of the siege of Orléans, however, is curiously perfunctory. He shoots the coronation less for pageantry than for physical comedy, with the Dauphin struggling with his massive robes. And a long shot of Joan leading the siege of Orléans is an elaborate visual appetizer for a battle sequence that does not take place.

Sometimes, Preminger is self-effacing to a fault. In the play there is a rousing moment at the end of scene two, when Joan has been charged with leading the army against the English invaders. “Suddenly flashing out her sword as she divines that her moment has come,” as Shaw writes, Joan cries out in triumph, “Who is for God and his maid? Who is for Orléans with me?” The character’s ecstasy demands a response from the medium, a bit of cinematic bravura—a burst of triumphal music, perhaps, a heroic camera movement, or a dramatic shift in lighting. Refusing to permit the film to do any “acting” of its own, Preminger keeps the camera at a neutral distance from Joan. His static shot of the Maid as she tentatively raises her sword and Seberg’s shaky whispering of lines that ought to ring with the weight of destiny defuse Shaw’s theatrical thunder.

In the trial scenes, however, Preminger’s conservatism yields many dividends. He ordered a week of rehearsals for the sequence, which he then shot over an intense two-week period. Fifty actors appear in the scenes, all without makeup and many wearing bald wigs. Quite unlike Carl Dreyer’s montage editing in The Trial of Joan of Arc, which separates Joan in isolating one-shots, Preminger in dispassionate, eye-level compositions often keeps the Maid and her prosecutors within the same spatial frame. Avoiding disfiguring low angles and providing only a few close-ups of Joan, he presents the trial objectively in a series of deep-focus long shots. The visual balance underscores the equality of both sides in the Shavian debate (“there are no villains in the piece,” as Shaw warned in his preface) and puts the emphasis in the right place—on Shaw’s dialogue.

Saint Joan, the most honorable failure in Preminger’s career, lost money and damaged the prestige he had accumulated as an independent filmmaker with three hits in a row. Would he and Jean Seberg bring each other better fortune on their next venture?

When midway through Saint Joan Preminger informed Jean that she was to star in Bonjour Tristesse, the project had already had a complicated history. In 1954, before publication and with no awareness of the success her little story was to achieve, Sagan had sold the rights to a French producer, Ray Ventura, for ten thousand dollars. A year later, early in 1955, when the book was selling briskly in twelve countries, had appeared on the New York Times best-seller lists for an astonishing thirty-eight weeks, and had sold over 1,300,000 copies in paperback, Preminger bought the rights from Ventura for a sum ten times what Ventura had paid the author. Otto’s initial plan was to extract a double dividend from his catch—before turning it into a film, he would first present Bonjour Tristesse as a play On August 5, 1955, he signed S. N. Behrman (whose favorite subject was the manners of the out-of-sight rich) to adapt the novel into both a play and a screenplay. Preminger announced that he would produce and direct Bonjour Tristesse on Broadway during the 1955–56 season and then shoot Behrman’s screenplay on location in the summer of 1956. No further word about the play ever appeared, but in the late winter and early spring of 1956, as he was preparing his search for Saint Joan, Preminger worked with Behrman on a screenplay. On April 6, the two sailed to France on the Liberté. From April 23 to May 10 Preminger served on the jury at the Cannes Film Festival and then joined Behrman in Antibes to continue to work on the script that he expected to shoot in July and August. As it happened, Otto didn’t shoot Bonjour Tristesse until the summer of 1957, and the screenplay was not by Behrman but another man of the theater, Arthur Laurents, the author of two successful plays and several screenplays, including Rope (directed by Alfred Hitchcock) and Anastasia.

Preminger was drawn to Sagan’s story of Cécile, an amoral young woman with an incestuous attachment to her father who indirectly causes the death of a rival for her father’s love. He admired Sagan’s casual attitude toward the rituals of the sweet life on the Riviera as well as her seductive evocations of landscape and weather. Arthur Laurents, however, did not share Preminger’s enthusiasm. “When I read Sagan’s book in French, I thought it was a hot fudge sundae that might well become a best seller, but I also thought it was a trick, and indeed it turned out to be her fifteen minutes,” Laurents recalled. “When I met her, I thought she was cultivating an attitude. She was pretending to be jaded, which she was too young to be. She was of the moment—it was chic to be depraved at that moment—and at the time she was taken seriously. A lesbian who lived a very fast life, she was quite unattractive, and that always helps to be taken seriously”33

Thinking little of the author or her novel (“I couldn’t have cared less about that story”), Laurents nonetheless accepted Otto’s offer to write a screenplay. “This was before I had written the libretto for West Side Story and I needed the money. I was recommended by Anatol Litvak, a friend of Otto’s for whom I had written Anastasia, but I think the real reason Otto hired me was because he knew I had lived in Paris in the early 1950s and had known all these degenerate people Sagan writes about.” Laurents was surprised, but also relieved, that as he wrote he had little contact with Preminger. “He really just left me on my own, with one basic instruction, that we are to be removed from the characters, who don’t have passionate emotions. Otto thought that kind of distance was ‘high style.’ From beginning to end he was terribly nice to me, and I found him amusing, cultured, and not too much of a director. He was never an ogre to me, but I’ve been called an ogre too, and I’m not.” Laurents wrote the script quickly—“it took two minutes”—and Preminger approved it without asking for any significant changes. He invited Laurents to be on the set throughout filming. “I declined. The only set I was on often was Rope, because Hitchcock needed a lot of dialogue in the background. Much later, I got asked to leave the set of The Turning Point.”

Laurents was indifferent not only because he felt no commitment to the story or characters but also because he disagreed with Preminger’s casting. “Why had Otto cast English actors like David Niven and Deborah Kerr to play French characters? And then, in the midst of this chic atmosphere, there is Jean Seberg—Miss Iowa.” Laurents had met Jean in Preminger’s suite at the Plaza Athénée when Otto had hired him.

She was lovely, but I felt she was “performing” as an innocent young American girl. When I suggested she order profiteroles for dessert, she said, “I’m so young I break out.” I was told that Otto liked to watch her take a bath. He turned on her when he found out she was sleeping with a French lawyer [François Moreuil, twenty-three,whom she was to marry on September 5, 1958]. He had thought she was a virgin, and he felt betrayed. He wanted to think of her as his virgin. European men don’t understand American women. Jean was posing, acting American innocence, and Otto had fallen hook, line, and sinker for this cornfield approach. He was besotted. An intelligent, cultured man, Otto had fallen for a hooker, Gypsy Rose Lee, and now for a “virgin,” and they are flip sides of the same coin. After I turned in the script, I saw Saint Joan and I immediately cabled Otto: “Jean will sink me, you, and the picture.” Preminger’s response was that Jean will be a “triumph.” I bet Otto five dollars that she wouldn’t be.34

Believing in Jean and confident that, unlike Saint Joan, Bonjour Tristesse had the ingredients to become a commercial as well as critical success, Preminger set up production offices in Paris and Cannes in early June 1957, almost two months before he was to begin shooting. One of his first staff appointments was Hope Bryce, a former model who was personally acquainted with many prominent designers and had once roomed with another model, Otto’s wife Mary. “I was hired as costume coordinator and given complete charge of the wardrobe department and the budget,” Hope recalled. “I worked with Givenchy on wardrobe and designed three of the dresses.” Over the summer, the elegant, reserved young woman, separated from her first husband, and Otto, by now long estranged from Mary and no longer seeing Dorothy Dandridge, “unexpectedly fell in love,” as Hope said. Although she had met Otto casually, when she and her first husband had socialized with Otto and Mary, she had had “no idea” that they would have a future. But as Hope, living in a garret at the top of the Plaza Athénée, spent time after hours with Otto, who was staying in “a magnificent apartment on the Île Saint-Louis filled with Vuillard paintings,” she became “enthralled” by the filmmaker’s energy and erudition. Although it might seem that Otto also satisfied a desire for the kind of strong male figure she had not had growing up—her father had died before her birth and she had been raised by her mother—Hope “never for one moment thought of Otto as a father figure.”

That summer, Hope had ample opportunity to observe Preminger’s “contradictions” and his “tantrums,” which neither intimidated her nor dampened her affection. “Otto was certainly variegated,” she said. When the French crew struck because they wanted wine at lunch, “we all thought Otto would explode. But no, when he knew he was expected to explode, he wouldn’t. He agreed to the request, and the French went back to work. No one liked to see Otto go into a rage, and cast and crew wondered who was going to be ‘it’ today,” she recalled.35 Hope herself, despite her closeness to the director, was not immune. “She sometimes got the same kind of rollicking as we all did,” said British production manager Martin Schute, who was to work for the director on three other films and to become “an expert in Otto Preminger-ship.” “If Hope saw some danger flying in the air, she would tip me off because she knew I could cure it.”36

As on Saint Joan, the coiled relationship between Preminger and Jean Seberg became the inevitable focus of the shoot. “When Otto’s assistant, Max Slater, ran lines with Jean, often you could see she wasn’t thinking about what the character was saying,” Hope Bryce observed.

Her eyes would look blank, and when Otto saw that vacant look, he’d start to scream, telling her she had to concentrate. He would only get angry when he felt she wasn’t trying hard enough. He saw the performance was in Jean, but he had to work hard to get it out of her. When Otto would yell, Jean’s chin would jut out and she’d start to cry, but I felt that she seemed able to act only when she got mad or was upset. I didn’t think Otto really intimidated her, though, and certainly Jean never talked back. But I did notice that the other actors were upset to see Jean upset.37

Deborah Kerr, playing Anne, Cécile’s prim rival who disapproves of la dolce vita, was dismayed.

I couldn’t stand it, when he was absolutely ranting and raving at poor little Jean Seberg. I said, “Please, Otto, do you have to shout at the poor little girl like that? She seems to be taking it all right but I’m not. I cannot work with this kind of atmosphere. I’m terribly sorry, but I just can’t.” The battering she received finished me, but it didn’t her. I used to be a bit frightened for Otto. I thought he was going to have a heart attack, with his eyes popping and his face purple. But the next minute, it was gone. Completely gone. And this man who could be such a bully on the set, and who could destroy people, would then be a charming, witty companion at dinner who knew the best wines and caviar.38

It wasn’t easy for Kerr to stand up to Otto (“She was very shy,” Hope said), but the actress felt she had to. Like everyone else, Preminger had great respect for Kerr and after she berated him he backed off, for the moment.

Geoffrey Horne, cast as Cécile’s boyfriend Philippe, “felt sorry” for Jean because Otto “yelled at her so much she was a basket case. But she did get through it somehow.” The actor remembered Seberg speaking up only once, when she got momentarily confused in a scene on a rowboat and called, “Cut!” which is not an actor’s prerogative, and was certainly a hanging offense on a Preminger set.

Otto went berserk; he seemed to get pleasure in going nuts, and it was not an act. I never saw him be affectionate with Jean. He was not really a father figure for her, and though there were rumors, which I did not believe, he certainly was not her lover either. I would have known if he had been her lover. He was an Old Testament God figure who was never inappropriate with the beautiful women who were on the set. He had some notion that Jean and I would become a couple, and that that would make the movie sexier. I was a naughty boy then and Jean and I flirted a bit, but Jean had a French boyfriend.39

Everyone admired Jean’s seeming ability to survive Otto’s explosions, but there was mixed reaction about her work. According to Deborah Kerr, Jean was “amazing in the role.”40 But Martin Schute felt that Jean “wasn’t particularly talented, and that was part of the problem. Otto wanted so much for Jean to be a star, which would validate his having chosen her for Saint Joan. But she was really a child at the time, more into her French boyfriend and reading press clippings about herself while Otto reckoned she should be concentrating entirely on her work.”41 Geoffrey Horne felt Jean’s acting was akin to her personality: “immature.”

I liked her, we all did, but there was something a little fraudulent about her, a conflict between the American girl she was and the European girl she was trying to be. She would walk into the makeup room in panties to show she was liberated, but it was fake. She was trying so hard to be sophisticated. She always had a mask, a disguise, which kept you from seeing her troubles and pain. But you could see it in her body and in her acting: she was stiff and awkward. There was no ease about her. She was pretty in close-ups, but not when she moved.42

Horne also received his share of the Preminger “treatment.” Trained by Lee Strasberg, Horne (who for decades has taught at the Strasberg Institute in New York) clashed with Preminger over interpretation. “I thought my role was a character part,” Horne said.

I knew I looked like a leading man—my looks got me lucky so young—but I felt like a character actor. I was good in neurotic parts, as unhappy, troubled, sensitive boys, which is how I saw Philippe. But Otto didn’t want that. He told me to stand there and do the part. “Be what you were the day I met you, and gave you the role,” he said. I had been very confident that day, because I had just returned from filming my part in The Bridge on the River Kwai. But I had a problem playing the kind of straight part he wanted, and Otto didn’t make me feel confident, the way Elia Kazan did at the Actors Studio when he would put his arm around me and make me feel I could do anything. David Lean [the director of The Bridge on the River Kwai] too had made me feel good, but Otto didn’t do that. He didn’t really seem to have any sense about actors as people. I don’t remember him directing for acting at all. “Stand here, move there,” he’d bark.43

With his two stars, David Niven and Deborah Kerr, Preminger observed a hands-off policy. “Otto didn’t have to say anything to Deborah Kerr: she was wonderful in the role, and she was generous, beautiful, and sexy, too,” as Horne said.44 Preminger also didn’t have to say much to Niven; as Raymond, Cécile’s sybaritic father, he was playing the same kind of role he had performed so deftly in The Moon Is Blue. Preminger and Niven were buddies who fraternized after working hours in Paris and on the Riviera. But one time Preminger blasted the actor in an incident that became famous, although nobody seems to remember it in exactly the same way. Niven’s biographer, Sheridan Morley set the scene on the Champs-Élysées, with Preminger berating the star for tardiness (Niven had been misinformed about the schedule) in a voice that could be heard “across several boulevards.” Niven managed to defuse the tirade by telling Preminger that he had “a terrible handicap. Whenever anyone shouts at me I forget all my lines.”45 Deborah Kerr recalled the blowup as taking place in the Bois de Boulogne, with Niven flummoxing his director by whispering, in a voice that could barely be heard, “Otto, don’t shout.” “David had his typical quizzical look—he had such a humorous face—and we all roared with laughter, including Otto, who just couldn’t hear what Niven was saying.”46 Martin Schute, who also set the scene in the Bois de Boulogne, recalled that the actor shouted back with a matching volume. “Eventually the terrific roar calmed down, and when it had, Otto turned to me and said, ‘It will be good for the newspapers.’ Otto never held any grudges.”47 Geoffrey Horne claimed the fracas took place in Cannes. “Niven had gone to Nice to gamble, because there had been a change in the schedule he hadn’t been told of.

When he showed up, late, with Otto looking purple, David said to him, ‘Otto, where the hell have you been?’ It was so funny and charming, and Otto laughed along with the rest of us.”48

Niven charmed Preminger and the cast, but was unpopular with the crew. “He was really a terrible mean bugger,” Martin Schute recalled. “He was impossible on the set and was often rude and nasty to his wife, Fjordis. ‘I don’t want your dirty wine in my glass,’ he said to her once at dinner. He wanted to walk away with his wardrobe, but I charged him and he argued like hell.”49 Rita Moriarty still in charge of Otto’s London office, recalled that “David always tried to be one of the boys with the crew, but it struck me as phony.” Her reservations about the actor may have been colored by an unnerving incident. “Though married, David, like Otto, was one for the ladies,” Moriarty said.

He had let Otto talk him into a “date” in London, where David was given Otto’s London chauffeur. David tipped the driver heavily, and then nobody knew where he was when it was time for him to return to France for shooting. Otto, frantic, called from Cannes to tell me I had to find him; but the chauffeur was getting well paid not to say where David was. I said I didn’t know, and then I spoke up and told Otto he had had no right to let David go off like that during a shoot. Otto knew he was wrong and perhaps as a result he started screaming at me over the phone. I could hear him pounding his desk, pounding it furiously for minutes on end. He was stammering with rage. I yelled right back at him.50

Despite the flare-ups, Bonjour Tristesse was a lucky shoot. The locations—Paris, Cannes, Le Levandou, Antibes—were heaven-sent. The weather for the entire filming, which lasted from late July to early October, was delicious. As always with Otto, the accommodations were strictly first class, as were the food and drink. At night, the day’s contretemps completely forgotten (by Otto if not always by those he had berated), Preminger was a world-class host, welcoming to all. And yet, despite the apparent extravagance, Preminger as always remained within the budget he had set. “Bonjour Tristesse was not a small movie,” Martin Schute recalled. “It was a major production of a best seller—at the time, Sagan was the sun, the moon, and the stars—and I had told Otto before filming that his projected budget of one and a half million was much too low. We had a terrific row. But I was naive, because Otto could do what others couldn’t. He brought the film in exactly as he had budgeted it—not a penny more.”51

Having survived another round with Preminger, Jean Seberg after five months in France returned to Marshalltown in mid-October accompanied by her French fiancé, François Moreuil. More than ever she felt like an outsider, and her high school friends as well as her family regarded her with suspicion: was she, they wondered, a young woman who knew too much? She had had an extraordinary year of great good fortune mixed with brutalizing disappointment; under enormous pressure, she had persevered. But when she returned to Marshalltown, she was unemployed. Preminger had not mentioned any upcoming project and she had nothing to look forward to except the opening in January of her new film, for which she might have wondered if she would receive another barrage of withering notices. At nineteen, was she already played out? François tried to lift her spirits as she made plans to move to New York to take acting lessons.

Preminger opened Bonjour Tristesse on January 15, 1958, without any of the fanfare he had lavished on his earlier independent productions. In a rare miscalculation, he booked the film into the inappropriately mammoth Capitol Theatre on Broadway, a movie palace with a huge, wide screen and over four thousand seats. “The theater could easily have seated the entire cast of Ben Hur,” as Arthur Laurents recalled. (“I met Otto at ‘21’ right after I had seen the film at the Moorish palace and I asked for my five dollars, because I didn’t think Jean was any better in Bonjour Tristesse than she had been in Saint Joan. Otto laughed, but I don’t remember whether or not he paid me.”)52 Geoffrey Horne also saw the film at the Capitol. “During a matinee opening week there were twenty-five people and acres of empty seats. I was on my way to a class with Lee Strasberg which was held above the theater.”53

For both Preminger and Jean Seberg the reviews were unsparing. In the New York Herald Tribune William Zinsser wrote that “Mlle. Sagan’s book is uniquely French, rueful and passionate, it is jaded in its view of sex, if not downright arch. But as directed by Otto Preminger it is as self-conscious as a game of charades played in an English country home. In the pivotal role, Jean Seberg is about as far from a French nymph as milk is from Pernod.” In the New York Times Bosley Crowther wrote, “As a literary effort, it was somewhat astonishing but thin. The same must be said for the movie that Otto Preminger has made from it—with the astonishment excited for the most part by the ineptness with which it has been done.” In his notice in the Saturday Review, Arthur Knight concluded that Preminger “apparently has not succeeded in convincing Miss Seberg that she is an actress.” The New Yorker’s suggestion for her was “a good solid, and possibly therapeutic, paddling.”54

Critical redemption arrived in March 1958, when, paradoxically, the film that American reviewers dismissed because it lacked a Gallic touch opened in France to a rapturous response. French critics saluted Preminger for his atmospheric handling of sun-baked settings and his treatment of characters with too much money and leisure time. Georges Périnal’s Cinema-Scope lensing was hailed for its plein-air magnificence. And this time most Parisian critics were intoxicated by Jean Seberg. Christened “the new divine of the cinema,” she appeared on the March cover of Cahiers du cinéma. Inside, in the most important review of her career, the young cinephile François Truffaut wrote about her performance and her screen presence with the kind of rhapsody that seems to be the exclusive province of besotted French critics. His ecstasy based on a misconception (he called the film “a love poem to [Jean Seberg] orchestrated by her fiancé”), Truffaut concluded that only a lover would be able “to obtain such perfection.” “This kind of sex appeal hasn’t been seen on the screen. It is designed, controlled to the nth degree by her director. When Jean Seberg is on the screen, which is all the time, you can’t look at anything else.”

Ironically, then, if Preminger on native grounds was dismissed as an impostor, to the French the Austrian-American director’s approach to French material seemed revelatory. Not distracted by (and looking beyond) the assorted accents of the cast, Parisian critics credited Preminger with wise insights about the national psyche. Nearly three decades after its release, the film continued to exert the same hold, as an article by Jean-François Rauget in 1986 in Cahiers du cinéma revealed. “The genius of Preminger completely bursts with the discovery of a musicality in the movements of the bodies and the characters’ consciousness. The film is some sort of abstract painting where the mixture of black and white with vivid colors, of a rocky and liquid nature with the psychological insignificance of the characters, brings forth a particular sensuality which Godard will remember for Le mépris.”

If, on the one hand, Bonjour Tristesse is indeed far sturdier than the original American reception suggests, and, on the other, not quite the incandescent achievement that many Gallic cinephiles have claimed it to be, it definitely casts a spell. In spite or perhaps precisely because of her flaws, if you love Jean Seberg, then you must also love the film. Her performance, like Preminger’s direction, is by turns problematic and sublime. In a strange way Jean’s fragility as an actress—her constricted movements, her masked expression, her untrained yet distinctive voice, shivery and enchanting—mirrors Preminger’s own inconsistency, his sometimes imperfect mastery of his own gifts. Seberg’s stiffness on-screen echoes the occasionally stilted quality of Preminger’s direction. No wonder he could not give up on her.

Seberg’s near-delirious unevenness is displayed right at the beginning. On a dance floor in an underground Paris club her body language is self-conscious. Then, in a following shot, scrutinizing herself in a mirror as her eyes fill with tears of self-condemnation, she eloquently limns the despair of an already jaded young woman trapped in la ronde. Ultimately her performance as a remote beauty with a capacity for casual destructiveness is bewitching.

A good part of the film’s visual enchantment derives from Preminger’s recurrent use of dissolves between black-and-white and color. For scenes set in Paris in the present, with a melancholy Cécile brooding about her responsibility for the death of her father’s fiancée as she moves aimlessly from one social event to the next, Preminger and Périnal use a slightly grainy black-and-white. For contrast, they shoot Cécile’s memories of last summer on the Riviera in sumptuous color. “I suggested the dissolves, which provided fluidity, but it was Otto who added the brilliant touch of setting off black-and-white against color,” Arthur Laurents recalled.55 In the first dissolve to the past, as color gradually saturates the black-and-white image, the effect is stunning—the cinematic equivalent of a coup de théâtre. Much of the action takes place in a villa (the home of Pierre Lazareff, a publisher) perched spectacularly on a hilltop in Le Levandou overlooking the Mediterranean. As rendered by Georges Périnal’s cinematography, the landscape—a pine forest next to the villa, the turquoise sea, rust-colored rocks along the shore—shimmers in a sparkling light.

Can a viewer drawn to the color and the bejeweled settings overlook the fact that Preminger’s three leads are not remotely French? Yes, since in all other ways David Niven and Deborah Kerr are ideally cast, while Seberg is a case unto herself. Skeptical viewers can perhaps regard Niven and Kerr as English vacationers on the Riviera and Seberg, who sometimes sounds as if she is translating her lines from another language, as a cosmopolitan young woman who has traveled widely with her father. With his usual aplomb, Niven plays a confirmed roué. Seberg mirrors Niven’s insouciant tone—it’s clear that their entente, often visually underlined by the matching outfits they wear, could not possibly include anyone else. As embodied by Deborah Kerr, brittle, genteel Anne is an outsider who could never understand or accept the rules of their game.

Once again, Preminger takes a dispassionate view of neurotic, well-to-do characters. Nonetheless, while the film recalls the pattern set by Laura, it also anticipates Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960) and Antonioni’s L’Avventura

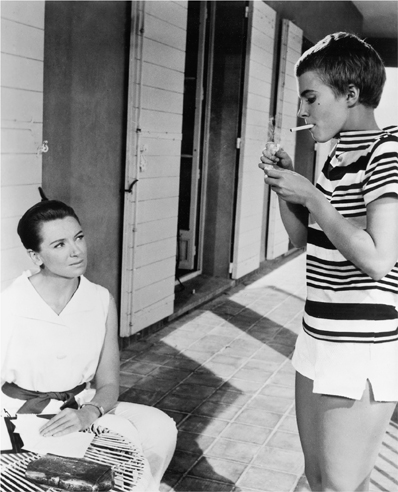

Anne (Deborah Kerr) looks uneasily at Cécile (Jean Seberg), the worldly young woman who will defeat her, in Bonjour Tristesse.

(1961), which also explore the alienation of the European upper bourgeoisie. The Italian films are far more ambitious than Bonjour Tristesse, but it was Preminger who first sensed the subject’s potential.

The director’s preference for wide-angle group shots gilds his chronicle of the easy life with a friezelike formality. It’s significant that when Cécile begins to feel threatened by Anne, Preminger places Cécile outside the group, hovering uncomfortably at the edge of the frame or isolated in a frame of her own. Because Preminger uses close-ups rarely, they carry a particular charge. In an early scene in a Parisian nightclub he cuts between close-ups of Cécile dancing absently with a new beau and a singer, the world-weary Juliette Greco, performing the title song; the editing enforces a comparison between Cécile, confronting her tristesse, and the melancholy torch singer. For the climactic moment in which Cécile has contrived to have Anne overhear Raymond flirting with a former paramour, Preminger keeps the camera tight on Anne with no countershot to “the lovers.” “I’ve always liked scenes where there’s no dialogue—they’re often, in film, more powerful,” recalled Deborah Kerr. “When Anne overhears the off-screen conversation, she has this awful realization that Raymond is unfaithful, and you see its impact without my saying anything. I thought it was terrific that my character’s big moment is conveyed without dialogue—just that close-up.”56

The film ends on a close-up of Jean (shot on the last day of filming, October 9, 1957, at Shepperton Studios, where the actress’s career had been launched with worldwide fanfare in January) that is a tour de force. Preminger wanted Seberg to be impassive, stripped of any readable expression, as she removes her makeup looking into a mirror. It is one of the beguiling paradoxes of this uneven, captivating film that, frozen-faced, her eyes filling with tears as Cécile faces a hollow future, Jean Seberg is intensely expressive. A cool, stylish beauty with ultra-chic, trendsetting short hair and wearing a smart black Givenchy cocktail dress, Jean Seberg in the last shot she was to make with her mentor looks like the real thing, a movie star who can also act.

In August 1958, eight months after Bonjour Tristesse bombed in America, François Moreuil persuaded Preminger to sell his contract with Jean to Columbia. “We simply had to get her out from under Otto’s thumb,” Moreuil, a lawyer, maintained.57 Preminger, however, reserved the right to use Jean in one film a year. “Otto did not think at the time, or later, that Jean had been that bad in Saint Joan,” as Hope recalled, “and he certainly would have used her again if he had had a part for her. But as it turned out he didn’t.”

Witnesses have testified to Preminger’s hard treatment of the unprepared young woman he had plucked from obscurity. He was, indeed, a demanding, impatient, and often wrathful mentor whose bullying tactics demolished her confidence. But no matter how many times he fulminated against her laziness and lack of focus, he also refused to give up on her. And on October 9, 1957, when she worked for him for the last time, she was a far stronger actress than she had been on January 7, when, in an apparent daze, she had shot the scene of Joan entering the court of the Dauphin. Otto Preminger made Jean Seberg famous, and perhaps only Jean could have told if her trial by fire had been worth it.

Without Preminger’s belief that she could portray Sagan’s character,

Seberg’s improbable second career in European films would not have happened. Jean-Luc Godard, admiring the aura, “the sense of being” that Preminger had created for Jean in Bonjour Tristesse, cast her in Breathless, where her wonderfully relaxed performance as an American Circe who loves and betrays a French hood transformed her from a Hollywood has-been into a leading figure of the French New Wave. Preminger must be given full credit for delivering “Jean Seberg” to Jean-Luc Godard, but he cannot be held accountable for her later despair, her descent into drugs and radical black politics, and, at forty, looking preternaturally aged, her suicide.

“Otto was really thrilled by Jean’s success in Breathless,” as Hope recalled. “He thought she was terrific in the film, and he was as proud of her as if she had been his daughter.”58 And after the film turned her into an international star, Preminger, vindicated at last, boasted, “I was right about Jean Seberg after all, wasn’t I?”59