If Bunny Lake Is Missing is “a small story,” Hurry Sundown, which Preminger worked on with Horton Foote as he was shooting in London, is just the opposite, an adaptation of a monumentally lengthy novel (1,064 pages) by Katya and Bert Gilden set in Georgia in 1946. Preminger had high hopes for the project. He had acquired the novel about eight months before its January 1965 publication. “I read it in a manuscript that Ingo showed to me,” Otto recalled. “It was very long, longer even than the published version, which is also very long, and I was fascinated by the people, and by the whole implication of the South in 1946 after World War II which, in my opinion, was the starting point of the civil rights movement.”1 Fully expecting the novel to become a best seller, Preminger had paid $100,000 for the rights and participated eagerly in all the prepublication fanfare organized by Doubleday the book’s publisher. On November 17, 1964, he had called a press conference where, with much ado, he revealed his plans to film the Gildens’ “great” novel. He also announced that his film would be a four-and-a-half-hour hard-ticket attraction that he would open in December 1966 in a handful of movie palaces at what was then the highest price scale in the history of American film exhibition. Otto promised he would charge twenty-five dollars for the best orchestra seats for the Friday and Saturday night performances, at which he was requesting that gentlemen wear black tie. (None of Preminger’s grandiose plans materialized.) “The novel has already been #2 on the best-seller lists for about 8 weeks,” he said in the Los Angeles Times on March 30, 1965, continuing to beat the drums. “Some critics say it is another Gone with the Wind. I certainly hope the picture is!” Despite Preminger’s and Doubleday’s persistent promotion, Hurry Sundown sold a respectable but not blockbuster 300,000 copies.

Preminger chose Horton Foote because he admired the writer’s adaptation of another Southern novel, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. Otto thought the Texan, whose plays about his home state are suffused with local color, would feel a kinship with the novel’s Southern setting and theme, but he didn’t seem to appreciate that Foote’s quiet style is far removed from the overripe manner of the Gildens, a married couple making their literary debut. “When Otto sent me the book I didn’t like it at all,” Foote recalled.

The authors had done their research all right, but they were not Southerners and nothing was authentic. There was no genuine Southern flavor at all. It was embarrassing. But I was younger then, and egotistical, and I thought I could do something with it. Otto brought my wife and children and me over to London and put us up in a house in Hyde Park where for three months we all lived high on the hog at Otto’s expense.

He was busy filming, but even so I saw him every day. He would make suggestions that I would obediently follow, and he seemed to like what I was doing. He was sharp as a tack. He laughed a lot with me—I guess I was the court jester. He wasn’t working on Bunny Lake every minute, and when he wasn’t he was a wonderful raconteur. And he was very sweet to my children. “Now keep them in line,” he’d say. Working every day with that far-fetched story [about the determination of two sharecroppers, a white man and a black man who have been lifelong friends, to prevent the sale of their adjoining land to corporate developers], I felt I was wrestling with unbeatable material. When I turned in a draft after three months I thought it was good, or at least as good as could be. After reading it—Otto had enormous confidence in his opinion—he said that we had different visions of the material. He wanted more melodrama and ultratheatricality than I gave him. I thought Otto was a wonderful filmmaker, but it wasn’t always my style—his story sense was different from mine. He could have insisted I go on working, but he didn’t. He paid me generously, exactly what he said he was going to. Then he hired Tom Ryan, who had worked for him and the next year had a success adapting Carson McCullers’s Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. Later Otto called and asked if he could put my name on the script. I was touched, actually, and I felt I owed it to him. I ask now, however, not to have it on my résumé. I never saw the final script or the film, and I don’t know how much of my work is there. Not much, I suspect.2

At the time Otto hired him, in the summer of 1965, Tom Ryan was in fact his chief reader. “He weighed about three hundred pounds, and when we shared an office at Columbia, he smoked me out,” Hope said. “He was talented and very bright—he was a walking encyclopedia and he retained every fact. Otto appreciated his skills in casting and as a reader. But Tom was bitter about his life: he was an unhappy homosexual who tried several times to commit suicide.”3 In August and September, as he was preparing for the opening of Bunny Lake, Preminger worked closely with Ryan, who was on his staff and in the office every day. He was pleased with Ryan’s approach— Ryan was giving him the “ultratheatricality” the Hollywood melodrama take on the material that he wanted. Over the fall, as he oversaw openings of Bunny Lake, Preminger began to assemble the large cast. To play the sharecroppers who resist selling their land, he chose two newcomers with stage experience, Robert Hooks and John Phillip Law. And in addition to court favorites Burgess Meredith, Doro Merande, and Diahann Carroll, he signed Michael Caine, Jane Fonda, Madeleine Sherwood, George Kennedy, Rex Ingram, and—to his infinite regret—Faye Dunaway Because, of course, he wanted to shoot the entire film on location, in Georgia where the Gildens had set the novel, he made several trips in November and December to line up settings. Although he knew the weather would be fierce, he was planning to shoot the film in the dripping humidity of June, July, and August.

In the midst of preproduction on Hurry Sundown he received unwanted headlines for an incident that took place at “21” on January 7, 1966. Seated next to the Premingers, who were dining with columnist Louis Sobol and his wife, were the agent Irving “Swifty” Lazar and his wife Mary. According to Lazar, Otto was determined to provoke an argument over a deal that had gone sour. Two years earlier, as Lazar recalled, Otto had wanted, prepublication, to buy the rights from him to Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and have Frank Sinatra star. “I’d given him some hope, but had carefully avoided saying anything binding. Which was just as well—when the book was finished, Truman decided we should sell it to Richard Brooks without inviting other bids. Left out in the cold Otto was miffed.”4 That night at “21,” according to Lazar’s recollection, Otto said that Sinatra was enraged and was planning to beat up the agent. To verify his claim Preminger demanded a phone so he could call Sinatra in Las Vegas at the Sands Hotel. “You’re making it impossible for us to remain here, Otto,” Lazar said. When he and his wife got up to leave, Lazar claimed that Preminger began to insult Mary. “You pitiable creature, I feel sorry for any woman who has to go home and go to bed with that crook,” Otto allegedly said to Mary Lazar. According to her husband, at that point Mrs. Lazar called Otto “a dirty old man” and slapped him. When Preminger rose up from his chair and raised his hand against Mary, Lazar reached for a glass and whacked Otto in the head with it. “Blood was streaming down Otto’s face as Mary and I beat a retreat,” Lazar contended.5 “I regret very much that it happened,” Lazar confided to columnist Earl Wilson. “For people who are not hoodlums these things are always regrettable. But I was provoked.”6

Otto denied that he had insulted Mrs. Lazar or that she had slapped him. “His wife did not take part in this at all,” he told Earl Wilson.7 “The argument had nothing to do with In Cold Blood,” as Hope recollected. “It was about Sinatra and Las Vegas: Swifty told us that he had just come from Sinatra’s opening in Vegas, but Otto knew that couldn’t be true; the opening wasn’t until later. When he said so, Swifty, a strange little man—I don’t know that he liked anyone—got annoyed. He stood, with a glass of scotch in his hand, and hit Otto. Hardly any words had been exchanged. The manager rushed Otto into the men’s room and called the ambulance. I called the police. Otto was conscious, but dazed.” Pictures of Otto exiting the restaurant with a puzzled expression and with his head bleeding profusely—he looked like the subject of a photo by Weegee, the chronicler of New York’s lower depths—were splashed across the next morning’s newspapers.

“The police wrapped his head in a towel and took Otto to New York Hospital, where a plastic surgeon had to remove pieces of glass from Otto’s scalp,” Hope said. “The operation required fifty-one stitches and Otto was in bed for the next three days. When the police asked Otto if he wanted to charge Swifty, Otto called our good friend Louis Nizer, who said yes, to go ahead.”8

In court on January 28, the combatants glared frostily at each other as Lazar pleaded not guilty. “The incident was not Otto’s fault, but because he always played the heavy he took the rap for it,” Hope said. Whatever the cause, the argument certainly reinforced Otto’s image as an ogre, a man you love to hate, and reflected poorly on him as well as Lazar. Both men behaved disgracefully, like petulant children. (A year later, on January 18, 1967, Lazar pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges of hitting Preminger, the original felony charge having been reduced months earlier, and was given a suspended sentence. “Otto was not litigious and decided not to sue,” Hope said. Years later, Lazar became a patient of Otto’s son Mark, at the time a cardiology intern. “When Mark asked me if he should become involved in the test I told him, ‘Of course,’ ” Hope said. “Mark told me that Swifty had asked him if he was a fellow who holds a grudge. He certainly is not, any more than Otto was. Mark conducted the test and happily, Swifty survived.”)9

The fracas with Lazar put Otto a few weeks behind on preproduction for Hurry Sundown, but by the beginning of February he was back on track. In late March, about eight weeks before his long-scheduled June 1starting date in Georgia, he had to change location because of a union dispute. When Preminger announced that because of the severe heat he would need to shoot at night and in the early morning starting at 6 a.m., the New York union (which had jurisdiction over the Georgia union) balked. They refused to alter a rigid 8:30 a.m. start time and demanded double time after 4 p.m. Preminger, who paid his crew above scale, claimed the costs of meeting the New York union demands would have been prohibitive. He had budgeted the film at a trim $3,785,000, compared to the $5,440,000 he had allotted the year before for In Harm’s Way, and he was resolved to remain within that sum.

Otto’s production designer, Gene Callahan, a native of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, suggested his home state as a possibility. Otto was persuaded, especially when he found out that Louisiana unions were under the jurisdiction of the Chicago union, more liberal than the one in New York. Still hoping to meet his June 1 starting date, Preminger in early April dispatched Callahan, along with Eva Monley once again his production manager, to line up locations. When they brought him down to Louisiana in late April to examine the sites they had selected, he was satisfied. “Otto trusted Gene on this because Gene was from the Deep South,” as Monley pointed out.10 Nonetheless, Preminger wanted to “enhance” the locations. To fit the needs of the story and, as Willi Frischauer wrote, “to lend verisimilitude to a big flood scene, Preminger hired a large local work force to build a big dam and a reservoir holding seventeen and a half million gallons of water. Cornfields were planted and sharecroppers’ cabins erected.”11

What Gene Callahan did not seem to realize, or what he had omitted mentioning to Preminger, was that they would be filming a story of an interracial friendship in the heart of Ku Klux Klan territory. “It’s like going to the Vatican to make a movie about Martin Luther, or going to a synagogue to make a film about putting down the Jews,” a local observer pointed out.12 Eva Monley booked office space for Otto and rooms for the more than one hundred members of the cast and crew at the Bellemont Motor Hotel, which over the entrance prominently displayed a Confederate flag. Trouble started at once. “It was evident from the first day of shooting that many of the local people didn’t want us there because we had a mixed cast,” Eva Monley said. “One day, on the wall of a set, there was a message from the KKK: ‘Eva Monley, go home.’ To protect me, I was made honorary sheriff. Going to and from the set I changed cars every day”13 Some of the extras and local crew were members of the local Klan, sent to spy and to cause disturbances wherever they could. Tires on company trucks were slashed. One morning at 3 a.m. a burning cross appeared on the set. The day after black and white members of the cast swam together in one of the motel’s two pools, local Klansmen made an abortive attempt to blow it up. “We had dared to pollute their sacred waters by allowing our mixed company to swim in it together,” noted Robert Hooks, who kept a diary of the production. When the manager informed Preminger that “no mixed bathing” was allowed on the premises, the filmmaker promised to remove his entire company from the motel and to default on the payment of the bill unless one pool were set aside for integrated swimming. “During the time that the pool was barred to mixed bathing, my kids said they wouldn’t go without their friends, the children of Diahann Carroll and Robert Hooks, who had come along with their parents at Otto’s insistence,” Hope said.14 The pool was integrated, but, as Hooks wrote, the Klan “labeled us ‘that nigger pitcher’ and they were determined to get us out of there, one way or another.” After armed state troopers were brought in to guard the wing of the motel where the cast and crew were housed, many of the actors began to feel as if they were under house arrest, their discomfort spiked by the paralyzing heat and humidity during summer on the bayou.

“It was beginning to dawn on us just what kind of place we had landed in,” Hooks noted.

The lesson was learned in somewhat different ways by different members of the cast. When Michael Caine was walking in downtown Baton Rouge with his friend [the journalist] David Lewin, a paunchy cop recognized him, which was not unusual, although his response was not what Michael was used to hearing from his fans. The sheriff looked him up and down and said he didn’t want him [or any of the actors in the film] in his town and he’d “bettah get his nigga-lovin’ ass the hell outah heah.” Michael was speechless. He hadn’t really believed what it was like in the American South in those days. But he did now.15

When Caine, along with Jane Fonda, Diahann Carroll, Rex Ingram, and Hooks drove into New Orleans one night, they were refused entrance at Brennan’s, a famous restaurant. “Michael could barely control his anger,” as Hooks recalled. “He asked the man if he knew who we were. The man did, but it made no difference. ‘What do you mean it doesn’t make any difference?’ Jane jumped in. She was ready to draw blood. The man said finally with a trace of irritation in his deep Southern drawl, ‘Say, don’t chall unnastan’? We don’ ’low no niggers in hyah. Thass it.’ Movie stars or not, in New Orleans in 1966, if you were black or hung out with blacks, Southern hospitality suddenly became Southern hostility.”16

On the way back to the Bellemont from a location one evening, as a line of cars and trucks was moving through a heavily wooded area, the twilight silence was abruptly shattered by a volley of gunshots. “We were being shot at by people we didn’t know, couldn’t see, and couldn’t defend ourselves against,” Hooks reported. “We were in a war in our own country.” The barrage lasted less than a minute before the Klansmen departed into the steaming wilderness. “Several windshields were blasted out and the sides of the

110° in the shade: A lunch break, with linen tablecloths, silverware, and good china, during shooting for Hurry Sundown, filmed on location in the summertime heat in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

cars were riddled with bullet holes, but by some great good fortune, no one had been hit or hurt,” Hooks wrote. “The shooters had made their point. All of us were convinced that we were surrounded by some of the dumbest and meanest people on the face of the earth, to say nothing of being the most cowardly”17

Madeleine Sherwood, playing a small-town bigot, received numerous telephone death threats. “Perhaps they were after me because I had been down south with the civil rights movement,” Sherwood reflected. “I’d spent time in jail and when I received a sentence of six months’ hard labor, I was the first white woman to be defended by a black lawyer. One night at the motel, after the seventh or eighth call, I was really scared, and I phoned Otto, who was a caring person and was concerned about all of us. ‘Come outside to the pool,’ he said. I met him there. He took my wrist in his hand and he raised both our hands and cried out, ‘Shoot!’ I was trembling. But thanks to Otto I never got another death threat.”18

“When I had to go shopping locally with Diahann Carroll to get a hat for her character, our driver said that I was to sit up front and Diahann had to sit in the back,” Hope remembered. “The governor [John McKeithen], a Democrat, kept asking us and some of the white stars to a dinner but didn’t invite any of the black actors. Otto didn’t accept the invitation.”19 Preminger retaliated by inviting the governor and his wife to attend a dinner he was hosting for visiting French journalists; the starstruck governor readily accepted, but was surprised to discover that Preminger pointedly had invited none of the film’s actors, white or black.

“Otto behaved beautifully through it all,” Eva Monley observed. “He refused to negotiate and continued to demand equal treatment for everyone in his cast and crew.”20 And despite the intimidation from local hoodlums and the heat, the director, as John Phillip Law enthused, was

the best host on a movie set ever. There we were in the middle of nowhere, threatened by the Klan, and every day under tents in the boiling sun we sat down to tables set with thick tablecloths, fine silver and china. There were no box lunches with Otto, but the finest food, as fine as you would get in the best restaurants in New York or Paris. And Otto would ask—and he really wanted to know—if our hotel rooms were okay. Nowadays you are just flown in and out; with Otto there was a real communal feeling. He kept his eye on his actors off the set, and in fact he might have saved my life. I was having a fling with a local girl who had a boyfriend who was a nut from Vietnam. When I took her home he jumped out of the bushes with a knife. He told me later he bought a pistol to kill me with, but then said he wanted to give it to me as a gift, and that I should meet him face to face in the lobby. Otto arranged with the local police to have him put in jail “until you guys leave town,” as the cops told me. Filming with Otto in Louisiana for three months was my golden age.21

Perhaps because of the us-versus-them atmosphere that overtook the location shooting, Preminger got on remarkably well with most of his actors. Michael Caine, with shrewd instincts about how to handle Otto, told him on the first day of shooting that he

knew of his reputation and that he should know that I was a very shy little flower, and if anybody ever shouted at me I would burst into tears and go into my dressing room and not come out for the rest of the day. He stared at me for a long moment and I waited to be bawled out immediately, as he was not used to being spoken to like this. Certainly he did seem a little taken aback. Finally, however, he smiled and said, “I would never shout at Alfie.” That was the key to the long friendship I subsequently enjoyed with this unpopular man.22 I used to have a go at him when he shouted at the other actors, however. “You’re scaring everybody. You’re getting everybody tense.” “I’m not, Alfie, I wouldn’t do this. They’re not afraid of me.” “They are all scared.” “Of me?” He was truly amazed that anyone was scared of him. He was a very abrasive man but his heart was in the right place at all times. Very much so. He was schizophrenic, because he could be two people. My favorite moment of observing Preminger—and I always watched him very closely—was in a hospital scene with Jane. It was a very, very hot day. And with the extra heat added by all the lights [that were needed to shoot the scene], the sprinkler system in the hospital was ignited. Otto went purple, his voice wouldn’t come, his eyes started to pop out of his head, and my God did he start to scream. And then, as we were getting drenched, we both started to laugh. I’d never heard Otto laugh out loud before. But he just started to laugh. A big, full, wonderful laugh—oh, it was gigantic and gorgeous, that laugh—because he realized the situation and his response were so ridiculous.23

“In the rushes Otto saw how good Jane was; he felt she was holding the film together,” Hope said. “Her politics weren’t at all apparent at the time and it wouldn’t have mattered to Otto anyway. She did her job, attended to her kids, and despite the fact that the Fondas had a reputation for being so icy she was friendly and warm to everyone.” “Jane was extremely disciplined, which of course Otto appreciated,” John Phillip Law said. “I lived with her and Roger Vadim [Fonda’s husband] while we were shooting Barbarella, and she ran the house, took ballet before being on the set, and was professional all the way. Jane was just as pleased as Otto about her work in Hurry Sundown, which she thought was her best until Klute.

“Otto yelled at me quite a lot, but I could just feel that he liked me, and so I was able to shuffle off things he would say to intimidate me,” Law said.

You had to know how to take him. He cast you because you were the archetype of what he wanted, but if you frustrated him by acting too much he’d start in on you. He didn’t approve of the Method, and one time when I was doing push-ups, which was my preparation for an emotional scene, he said, “This is not a gymnasium, Mr. Law, I pay you to act, not to exercise.” Even though asking him to do another take was like getting dispensation from the pope, I felt secure with him in a way I hadn’t with Elia Kazan, who had just directed me in the leading role in The Changeling at Lincoln Center. I felt Kazan resented good-looking guys, but Otto didn’t—he was above it all. For a love scene with Faye Dunaway, who was playing my wife, he said, “Roll over, you have a nice-looking backside.”24

Madeleine Sherwood, devoted to Lee Strasberg and an Actors Studio member, had exactly the kind of training Preminger had no patience for. But he hired her anyway because he had admired Sherwood’s vivid performances as Southern-fried crackpots in both the stage and film versions of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Sweet Bird of Youth and thought she was right for the role. “I developed a good character and Otto thought so too. I asked for props: a box of chocolates, curlers for my hair; Otto laughed and thought they were fine. His focus was the shot, and he was totally absorbed with the technical side, with lighting and placement, and he did not impose any kind of direction on me, or on Burgess Meredith who played my husband. I didn’t like German people then; I recalled World War II, as people of my age did. But I really and truly liked Otto—I enjoyed him.”25

“Something just clicked between Otto and me,” Robert Hooks said.

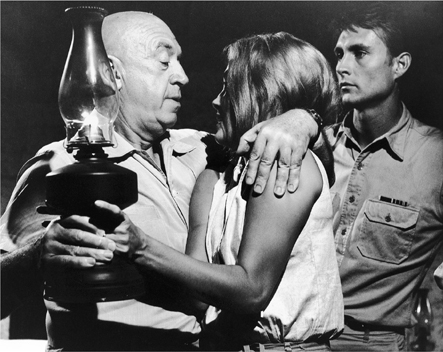

Preminger showing John Phillip Law how to kiss Faye Dunaway. Throughout the filming of Hurry Sundown, Preminger and Dunaway were bitter antagonists.

“We had one incident when I got my hair cut too short, but I just liked and admired Otto. I lost my father when I was young and Otto in a sense became my father.”26

The goodwill stopped here. If, as some of his colleagues attested, Otto could not function creatively in a conflict-free zone, if he needed somebody to be “it” on each production, in Faye Dunaway, neither then nor later a likely candidate for Ms. Congeniality, he was handed a gift from the gods. From the start Preminger and Dunaway looked each other over and did not like what they saw. As Hope said, “Otto never hated actors—he was simply not a hater. But he hated Faye Dunaway. Otto thought she was the toughest cookie he’d ever met, and she thought Otto was an idiot.”27 Indeed she did. “Otto was one of those directors you can’t listen to because he doesn’t know anything at all about the process of acting,” she maintained. Dunaway, a Southerner playing a character who she felt resembled her own mother, was certain she knew best. “I didn’t think [Otto] was ever right. Later I was to work for Roman Polanski… who was just as autocratic and dictatorial in many ways as Otto, but he was a good filmmaker. And Otto wasn’t.”28

Dunaway claimed that Preminger screamed at her only once, when she challenged him after he “went crazy and began yelling at Freddy [Jones],” a hairdresser who, she felt, seemed “defenseless.” “Otto turned on me like a mad dog and went at me. … I think it’s the only time I’ve really looked full in the face at somebody who’s gone into that complete state of rage… . For the duration of the film, Otto never raised his voice to me again, though there was no attempt to smooth things over either,” Dunaway recalled. “There was only that one time, but that’s all I needed. Once I’ve been crossed, I’m not very conciliatory.”29

About that there is no doubt; but a number of witnesses contradicted Dunaway’s self-serving account of her feud with Preminger, maintaining that the screaming never stopped. “Faye was the whipping boy on the set, and she and Otto fought the whole way through,” Michael Caine said.30 “Everybody could see the anger between them, and it was not pretty,” Madeleine Sherwood corroborated.31 John Phillip Law suggested that the ill will began with “the love scene Faye and I had worked so hard on. As I was bending down, Otto said, ‘Stop, you don’t know how to kiss a girl. You don’t bend over, you bring her up to you.’ Then he banged our heads together. It gave her a fat lip. Faye, a tough gal, was not too pleased.”32

For the only time in his career, Preminger’s “whipping boy” did not have the sympathy of the cast and crew, because Faye Dunaway, hard-bitten, competitive, and self-centered, managed to alienate everyone. “Ms. Dunaway did not defend the hairdresser, as she claimed: quite the opposite, she insisted on getting him fired,” as Hope recalled.

But that was only one of her many misdemeanors. She took over an air-conditioned trailer and banished dear Diahann Carroll who was to have shared the trailer with her. She made Diahann learn her lines outside the trailer, in the heat. She was insolent to the crew. She was incredibly slovenly about her personal appearance. She wasn’t even nice to John Law, when everybody else loved him—he is a wonderful man, so friendly, and he was terrific with our twins. Ms. Dunaway was even rude to them. She tried to have an affair with Michael Caine, because he was the biggest star on the set.33

(When the shooting ended, the actress took her employer to court to win her release from the five-picture contract she had signed with him. “I could not imagine doing another five films with this man,” she said. The

“How do you know how a black woman would feel and act, white man?” Beah Richards said to Preminger as Robert Hooks looked on during a rehearsal for a key scene in Hurry Sundown.

case dragged on until March 1968, when an out-of-court settlement was reached. “It cost me a lot of money to not work for Otto again,” Dunaway admitted. “I paid him, I paid his attorneys, I paid my attorneys. I regret paying him. … I thought he was awful to work with… . Otto never had another big hit,” she noted, gracious as ever.)34

In his single contretemps with a black performer Otto played a losing hand. As Robert Hooks reported, Beah Richards,

much to everyone’s surprise … effectively stood up to Otto. It happened the day she and I [Richards was playing Hooks’s mother] were shooting the scene where she dies. It was a beautiful, sensitive scene, and she was putting her whole heart and soul into it. Her performance was brilliant. It even made members of the crew cry. But for some reason Otto didn’t like it, which no one but him ever understood. He kept asking her to do it over and over, and we would, much to Beah’s irritation. Each time she would do it with the same depth of feeling as she had done before and each time he was not satisfied. Finally, he rode her about it once too often. Beah looked up at him with an expression I was glad was not directed at me, and said, “How do you know what a black woman in this situation would feel and act? What do you know about it, white man?” There was absolute dead silence on the set… . We all waited with baited breath for the explosion. Otto didn’t say anything at first. Finally he said, “Let’s try it once again, please.” And we did. And it was just as gripping as before. When it was over, Otto just sat there for a moment, then sighed and turned to his cameraman and said, “Print it. Let’s move on.” And we did.35

The heat, the Klan, and Faye Dunaway took their toll, and during the three-month shoot Preminger had a number of blowups. He fired a script girl and a secretary. As John Phillip Law recalled, “On the way to work one day Otto said to a cop, ‘You’re fired!’ ‘I don’t work for you, sir,’ the cop responded. ‘You’re fired anyway!’ Otto steamed.”36 Mystifyingly, he also dismissed Gene Callahan, the production designer who had found the location and negotiated all the construction contracts. “I was notified by an assistant while I was in the hospital recovering from an operation,” Callahan said. “That’s the way Otto does business. I still don’t know why he fired me.”37 Preminger also fired his screenwriter, Tom Ryan. “Before we started shooting Otto had hired a few brushup writers who usually don’t want credit,” Hope said. “As we were shooting Tom kept muddling around with the script and would bring in suggestions, which is not a good idea with Otto, who did not make or welcome script revisions once he began shooting. But Otto really blew up at Tom because when Rex Reed (Tom and he were good friends) came to the location to write a piece for the New York Times, Tom gossiped about the cast to Rex. Otto got very cross. ‘You don’t do this,’ he said. (After Otto fired him, we never heard from Tom again.)”38

Rex Reed’s article, “Like They Could Cut Your Heart Out,” which appeared in the New York Times on August 12, 1966, was certainly unflattering—Reed characterizes Otto as an autocrat who seems to be losing his grip. But it is no worse and perhaps even a little milder than other pieces over the years that had contributed to the filmmaker’s reputation. Nonetheless, it cut to the quick. “When the article appeared it was full of the grossest misstatements and described me as a ruthless tyrant,” Preminger, uncharacteristically, complained, as if he were hearing something new about himself. He objected particularly to a quote from Michael Caine: “He’s only happy when everybody else is miserable. Still, if you can keep his paranoia from beating you down, you can learn a lot from this guy.” In his autobiography Preminger took pains to point out that after the article appeared Caine wrote a disclaimer to the New York Times explaining that he had not known what “paranoid” meant and that after looking it up, “I can assure you, paranoid Otto is not.” Preminger also resented Reed’s claim that “in a moment of uncontrolled fury” he had fired his cameraman, Loyal Griggs. “The truth was that [Griggs] had to quit because of a back injury and kept on working in spite of pains until his replacement [Milton Krasner] arrived from California. I was not troubled by [Reed’s] lies,” Preminger protested, unconvincingly “but Griggs, through his lawyer, demanded and received a retraction from the New York Times.”39

Preminger did not succeed in winning over the Deep South in the way he had conquered Israel, Washington, the Vatican, and Hawaii on his other recent shoots. His sense of racial fair play could make no real dent in the racism that had infected the Louisiana bayou for generations. His victory was in finishing on schedule with all of his cast and crew still alive. At the end of filming he addressed the Louisiana legislature. “I spoke of the right we enjoy to disagree without fear,” he said afterward.40 “Governor George Wallace [of Alabama], who at the time was not allowing buses to unload black children at white schools, spoke first,” Hope recalled, “and then Otto spoke. ‘I am a naturalized American citizen and only in America could such two diametrically opposed speakers share the same podium,’ he said, and he got a standing ovation.”41

In September 1966, as he was editing Hurry Sundown, Preminger, to please his six-year-old twins, accepted the role of arch-villain Mr. Freeze, who thrived in temperatures under fifty degrees below zero in the television series Batman. (Formerly the part had been played by George Sanders, whom Preminger had directed at Fox in Forever Amber and The Fan) Dressed in a jumpsuit, with purple lips, curled bright red eyebrows, and his head and face painted blue, Otto cheerfully parodied his image. After devoting a full day to makeup tests, for one week he reported to work daily at 6:15 a.m. and remained on the set until seven in the evening, when he was driven to the editing rooms of MGM to continue cutting Hurry Sundown. His one request, quickly granted, was a private phone on which, when he was not needed on the Batman set, he would confer with his two veteran editors, Lou Loeffler and James Wells. For the entire week Preminger earned an A for conduct. “It is much easier being an actor than a director,” he said. “You just take orders. They tell you where to stand and what to say. You become a child again. It’s play”42

Although Preminger and his editors managed to trim the Gildens’ 1,064-page novel into a comparatively meager 146 minutes, many reviewers, along with a host of other gripes, complained of Hurry Sundown’s excessive length. “Sheer pulp fiction … an offense to intelligence,” Bosley Crowther wrote in the New York Times on March 24, 1967. More tolerantly (and accurately), Variety saluted Preminger for “a hard-hitting and handsomely produced film about racial conflict in Georgia circa 1945. Told with a depth and frankness possible only today, the story develops its theme in a welcome, straightforward way that is neither propaganda nor exploitation.” As Madeleine Sherwood correctly claimed, “Otto was trying to deal with racial issues in a way that at the time nobody else was. The film was dismissed out of hand in 1967, but now it should be regarded as an important piece of history. Yes, it’s too long, it goes all over the place, there are too many stories— but really, it’s a wonderful bad movie.”43

And so it is. Despite the charges that can be leveled at Hurry Sundown— that it is a simplistic view of the Deep South by a team of outsiders; that it is contrived, meandering, overplotted—it is another example of Preminger tackling previously off-limits subject matter. This time, though, he didn’t get any credit for taboo smashing. And other, more modern-seeming films on race relations such as In the Heat of the Night and To Sir with Love (which were released after Hurry Sundown) earned praise while Preminger’s epic was branded with an ill fame it doesn’t merit.

As a white liberal’s utopian view of racial integration, Hurry Sundown is ideologically, if not artistically, immaculate. The film treats the Negro characters with notable respect. Neither saints nor holy victims, on the one hand, nor militants bristling with rage and rhetoric, on the other, the characters, in a way that was rare at the time, transcend stereotype. And Preminger places them carefully within the period of the story, 1946, rather than imposing a 1966 perspective on them. Neither Reeve (Robert Hooks) nor his girlfriend (played by Diahann Carroll), who has been educated in the North, is played as a contemporary 1960s firebrand. Rather, it is Reeve’s mother Rose (Beah Richards, magnificent) who, in her deathbed epiphany, expresses the kind of anger that will lead to the civil rights movement. “I was wrong,” she announces to her son. “I was a white folks’ nigger [who] help[ed] them to do it [to me]. I grieve for this sorry thing that has been my life.”

In his usual fashion Preminger attempts to be fair to “the other side” as well. Some of the white characters, like the racist Judge Purcell and his shrewish, social-climbing wife Eula (Burgess Meredith and Madeleine Sherwood) are beyond reclamation. But the central characters representing white privilege (played by Jane Fonda and Michael Caine) are not. Fonda reveals her character’s growing awareness of the tainted legacy she will ultimately reject. And Caine discovers in his grasping capitalist a vein of regret.

There are many familiar Preminger touches: beautifully orchestrated

There are empty seats in the room but blacks have to stand in the back, a social point made unobtrusively by Preminger in this long shot in Hurry Sundown. (The witnesses: Jane Fonda, Michael Caine, and Robert Hooks.)

tracking shots that follow the characters walking through scenic locations; objective, frontally staged group shots that reveal connections among the characters; meaningful deep-focus compositions, as in a scene in a courtroom in which blacks are made to stand against the rear wall despite there being many empty seats. A heroic, high-angle helicopter shot at the beginning introduces the land that the white and black sharecroppers will fight for with a determination recalling the pioneers in Exodus. But there are some shortcomings here. Preminger undermines the sweep of some of his tracking shots with nervous cutting. More crucially, the South that the film depicts resembles a studio-era confection, a constructed world from which the warp and woof of reality have been more or less excluded. Despite the fact that all the exteriors were shot on location, the settings are curiously antiseptic. Poverty and architectural decrepitude have been carefully excised, and notwithstanding the enervating heat the characters always look suspiciously fresh. Interiors, many shot at MGM, are also too manicured, adding to the film’s “made-in-Hollywood” aura.

It’s tempting to speculate that as a story of race relations in America, with a vivid cast of local racists, visiting movie stars both nice and monstrous, and a good-hearted, temper-prone director, a film about the making of Hurry Sundown might have been more pertinent. Business was respectable—rentals were just over $4 million as against a budget of just under $3.8 million—but hardly encouraging. In spite of its fresh subject for the time, Hurry Sundown is stodgy, its earnest tone and multistranded narrative throwbacks to a kind of moviemaking that seemed almost fatally out of step with the new Hollywood struggling to reflect the counterculture emerging in the late 1960s.

As he was well aware, Preminger was no longer an industry trendsetter. Concerned about making a place for himself at a time of great change both within and outside the film business, on his next project he attempted to banish “Otto Preminger.”