4. Should You Think Like an Economist?

When difficult cases [decisions] occur, they are difficult chiefly because while we have them under consideration, all the reasons pro and con are not present to the mind at the same time … To get over this, my way is to divide half a sheet of paper by a line into two columns; writing over the one “Pro,” and the other “Con.” Then … I put down under the different heads short hints of the different motives … for and against the measure … I endeavor to estimate their respective weights; where I find one on each side that seem equal, I strike them both out. If I find a reason pro equal to two reasons con, I strike out three … and thus proceeding I find at length where the balance lies … And, though the weight of reasons cannot be taken with the precision of algebraic quantities, yet when each is thus considered, separately and comparatively, and the whole lies before me, I think I can judge better, and am less liable to take a rash step.

—Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin’s suggestions about how to deal with choice are what we now call decision analysis. His procedure is a more detailed account of a method for decision making initially proposed in the middle of the seventeenth century by the mathematician, physicist, inventor, and Christian philosopher Blaise Pascal. In carrying out what is called expected value analysis, you list the possible outcomes of each of a set of choices, determine their value (positive or negative), and calculate the probability of each outcome. You then multiply value by probability. The product gives you the expected value of each course of action. You then pick the action with the highest expected value.

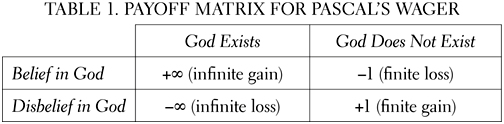

Pascal described his decision theory in the context of considering his famous wager: Everyone has to decide whether to believe in God or not. At the heart of his analysis was what we would call today a payoff matrix:

If God exists and we believe in him, the reward is eternal life. If he exists and we do not believe in him, the consequence is eternal damnation. If God does not exist and we believe in him, there is a loss that is not too substantial—mostly forgoing guilty pleasures and avoiding selfish behavior that harms others. If God does not exist and we disbelieve, there is a relatively minor gain—indulging those guilty pleasures and behaving selfishly. (I note parenthetically that many psychologists today would say that Pascal may have gotten the finite gains and losses reversed. It actually is better for your well-being to give money than to receive it,1 and kind consideration of others makes one happier.2 But this doesn’t affect the logic of Pascal’s payoff matrix.)

Pity the poor atheist if Pascal got the payoffs right in the event that God exists. Only a fool would fail to believe. But unfortunately you can’t just grunt and produce belief.

Pascal had a solution to this problem, though. And in solving the problem he invented a new psychological theory—what we would now call cognitive dissonance theory. If our beliefs are incongruent with our behavior, something has to change: either our beliefs or our behavior. We don’t have direct control over our beliefs but we do have control over our behavior. And because dissonance is a noxious state, our beliefs move into line with our behavior.

Pascal’s prescription for atheists is to proceed “by doing everything as if they believed, by taking holy water, by having Masses said, etc.… This will make you believe … What have you to lose?”

Social psychologists would say that Pascal got it just right. Change people’s behavior and their hearts and minds will follow. And his decision theory is basically the one at the core of all subsequent normative decision theories.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

An economist would maintain that, for decisions of any consequence at all, you have to conduct a cost-benefit analysis, which is a way of calculating expected value. The formal definition of cost-benefit analysis is that the action that has the greatest net benefit—benefit minus cost—should be chosen from the set of possible actions. More specifically, one should do the following.

1. List alternative actions.

2. Identify affected parties.

3. Identify costs and benefits for each party.

4. Pick your form of measurement (which will usually be money).

5. Predict the outcome for each cost and benefit over the relevant time period.

6. Weight these outcome predictions by their probability.

7. Discount the outcome predictions by a decreasing amount over time (a new house is worth less to you twenty years from now than it is now because you have less time left in your life to enjoy it). The result of the discounting is the “net present value.”

8. Perform a sensitivity analysis, meaning one adjusts the outcome of cost-benefit analysis due to, for example, possible mistakes in estimating the costs and benefits or errors in estimating probabilities.

Needless to say, all this sounds daunting, and it actually leaves out or simplifies some steps.

In practice, a cost-benefit analysis can be considerably less complicated than what’s implied by the above list. An appliance company might need to decide whether to put out either one or two colors of its new juicer; an auto company might need to decide between two versions of an auto model. The costs and benefits are easy to identify (though estimating probabilities for them can be very difficult), money is the obvious measure, the discount rate is the same for both options, and the sensitivity analysis is relatively easy to perform.

Decisions by individuals can be similarly uncomplicated. Let’s consider a real one confronted by a couple who are friends of mine. Their old refrigerator is on its last legs. Choice A is to buy an ordinary refrigerator like most people have, costing in the range of $1,500 to $3,000, depending on quality and features such as ice maker and water cooler. Such refrigerators have some unattractive features, a repair record that’s not great, and a relatively short life expectancy—perhaps ten to fifteen years. Choice B is to buy a qualitatively different kind of refrigerator that is extremely well built and has many attractive features. It functions beautifully, its repair record is excellent, and it can be expected to last in the range of twenty to thirty years. But it costs several times as much as an ordinary refrigerator.

Calculating expected value is not terribly difficult in such a case. Benefits and costs are pretty clear, and it’s not all that difficult to assign probabilities to them. Though the choice might have been difficult for them, my friends can feel comfortable about their decision because they had considered everything they ought to have, and they had assigned reasonable values for costs and benefits and for the probabilities of those costs and benefits.

But consider a somewhat more difficult choice involving assessment of multiple costs and benefits. You’re considering buying either a Honda or a Toyota. You do not—or should not—buy a Honda whose assets, taken as a whole, are of value X rather than a Toyota whose somewhat different assets, taken as a whole, are also of value X—if the Honda is more expensive.

Well, of course. But the devil is in the details.

Problem number one is how to limit the choice space—the options you’re going to actually consider. Who said you should be choosing between a Honda and a Toyota? How about a Mazda? And why stick with Japanese cars? Volkswagens are nice and so are Fords.

Problem number two is when to stop searching for information. Did you really look at every aspect of Hondas and Toyotas? Do you know the expected gasoline consumption per year? The relative trade-in values of the two cars? The capacity of the trunk? The optimizing choice—making the best decision possible—is not a realistic goal for many real-world decisions. If we really tried to optimize choice, we would be in the position of the philosopher’s donkey starving between two bales of hay. (“This one looks a little fresher. Looks like there’s more hay in that one. This one is a little closer.”)

Enter the economist–political scientist–psychologist–computer scientist–management theorist introduced in the previous chapter, namely Herbert Simon. He attempted to solve these two problems with cost-benefit theory. It’s often not rational, he says, to try to optimize choice. It’s the thing to do for a high-speed computer with infinite information, but not for us mortals. Instead, our decision making is characterized by bounded rationality. We don’t seek to optimize our decisions; rather we satisfice (the word is a compound of “satisfy” and “suffice”). We should spend time and energy on a decision in proportion to its importance. This amendment to standard microeconomic theory is surely correct as far as it goes, and Simon won the Nobel Prize in economics for this principle. People who spend ten minutes deciding between chocolate and vanilla are in need of help. And, on the other hand, “Marry in haste, repent at leisure.”

But there’s a problem with the concept of satisficing. It’s fine as a normative prescription (what you should do), but it’s really not a very good description of the way people actually behave. They may spend more time shopping for a shirt than for a refrigerator and exert more energy pricing barbecue grills than shopping for a mortgage rate.

For a spectacular example of poor calibration of choice time in relation to choice importance, consider that the most important financial decision that most academics ever make takes them about two minutes. When they go to fill out employment papers, the office administrator asks how they want to allocate their retirement investments between stocks and bonds. The new employee typically asks, “What do most people do?” The reply comes back, “Most people do fifty-fifty.” “Then that’s what I’ll do.” Over the past seventy years or so, that decision would have resulted in the professor netting substantially less money at retirement than he would have with a decision for a 100 percent stock allocation. (But remember, I’m not a real financial analyst. And if you’re going to follow my advice despite my lack of expertise, do remember that some analysts advise that a few years before retirement, you should take a considerable amount out of stocks and put it into bonds and cash so that you suffer less damage should the stock market be in a trough at retirement time.)

So what’s a reasonable amount of time to spend on a decision to buy a car? Of course, what’s reasonable differs from person to person. Rich people don’t have to worry about which options they should choose. Just get ’em all! And if rich people have bad outcomes because they hadn’t calculated probabilities correctly, they can just throw some money at the problem. But for most people a few hours or even days given over to research on automobiles seems sensible.

Now consider an extremely complicated and consequential choice. Here’s a real one that was confronting a friend at the time of this writing.

My friend, who is a professor at a university in the Midwest, was recently made an offer by a university in the Southwest. The university wanted my friend to start a center for the study of a field of medicine that my friend had cofounded. No such center existed anywhere in the world, and medical students and postdoctoral fellows had no place to go to study the field. My friend is eager for there to be such a center and would very much like to put his stamp on it.

Here’s a partial list of the costs and benefits he had to calculate.

1. Alternative actions were easy: go or stay.

2. Affected parties: my friend, his wife, their grown children, both of whom lived in the Midwest, potential undergraduate students, medical students and postdocs, the world’s people at large—since there are considerable medical implications of any findings in my friend’s field and it’s possible that there would be more such findings if there were a center devoted to this field.

3. Identifying costs and benefits for my friend and his wife were a mixed bag. Some of the benefits were easy to identify: the excitement of starting a new center and advancing his field, escaping midwestern winters, a higher salary, a change of intellectual scenery. Assessing the probabilities of some of those things, not so easy. Some of the costs were equally clear: the hassles of moving, the burdens of administration, southwestern summers, leaving treasured friends and colleagues. But impact on the world? Very difficult to contemplate: no way to know what the findings might be or even how much more likely they might be if my friend, rather than someone else, took the helm of the center. Benefits and costs to my friend’s wife were fewer to calculate because her occupation as a novelist was portable and wouldn’t change, but values and probabilities were difficult to estimate for her as well.

4. Measurement? Money works for salary. But how much is it worth to have a sunny January day with a high of sixty degrees versus a cloudy January day with a high of twenty? How much is the estimated excitement and pleasure of setting up a center offset by the aggravation of trying to recruit staff and administer the center? How about the benefits and costs (monetary and otherwise) for discoveries as yet unknown? Hopeless.

5. Discounting? Works well for salary, but difficult to impossible for most of the rest.

6. Perform a sensitivity analysis? What to say other than that the possible range of values for most of the benefits and costs is very large?

So why do the cost-benefit analysis at all, since there are so many imponderables?

Because, as Franklin said, your judgment will be better informed and you will be less likely to make a rash decision. But we shouldn’t kid ourselves that the exercise is always going to come out with a number that will tell us what to do.

A friend of mine once carried out a cost-benefit analysis for an important move she was considering making. As she was nearing the end of the task, she thought to herself, “Damn, it’s not working out right! I’ll have to get some pluses on the other side.” And there was her answer. As Pascal said: “The heart has its reasons of which reason knows nothing.” And as Freud said, “When making a decision of minor importance, I have always found it advantageous to consider all the pros and cons. In vital matters, however … the decision should come from the unconscious, from somewhere within ourselves.”

My friend’s heart quite properly overruled her head, but it’s important to be aware of the fact that the heart is also influenced by information. As I pointed out in the previous chapter, the unconscious needs all possible relevant information, and some of this information will be generated only by conscious processes. Consciously acquired information can then be added to unconscious information, and the unconscious will then calculate an answer that it delivers to the conscious mind. Do by all means perform your cost-benefit analysis for the decisions that really matter to you. And then throw it away.

Institutional Choice and Public Policy

To this point I’ve skirted around a big problem for expected value theory and cost-benefit analysis. This is the problem of how to compare the apples of cost with the oranges of benefits. For institutions—including the government—it’s necessary to compare costs and benefits with the same yardstick. It would be nice if we could compare costs and benefits in terms of “human welfare units” or “utilitarian points.” But no one has come up with a sensible way to calculate those things. So normally we’re left with money.

Consider how one might do a cost-benefit analysis for a highly complicated policy decision. An example might be whether it pays to have high-quality prekindergarten day care for poor minority children. Such an analysis has actually been carried out by the Nobel Prize–winning economist James Heckman and his colleagues.3 Alternative actions—high-quality day care versus no day care—are easy to specify. Heckman and company then had to identify the affected parties and estimate benefits over some period, which they arbitrarily determined would end when the children reached age forty. They had to convert all costs and benefits to monetary amounts and pick a discount rate. They didn’t have to estimate the probability and value of all the cost and benefit outcomes because some of these were known from previous research; for example, savings on welfare, savings due to lowered rate of special education and retention in grade, cost of college attendance for those who went to college, and increase in earnings by age forty. Other outcomes had to be estimated. The cost of the high-quality day care compared to the cost of ordinary day care (or lack of day care at all) provided to children in the control group was estimated, though not likely to be too far off.

Heckman and company calculated the cost of crime based on the contention that crime costs $1.3 trillion per year. This in turn was based on estimates of the number and severity of crimes derived from national statistics. But the crime cost estimate is shaky. National statistics on crime, I’m sorry to tell you, are unreliable. Estimates of the number and type of crimes committed by the preschoolers by the age of forty, based on individuals’ arrest records, are obviously also very uncertain. The reduction in likelihood of abuse or neglect for an individual as a child, and then later when that child becomes an adult, is difficult to assess or assign a monetary value. Heckman and company simply assign it a value of zero.

Identifying all the parties ultimately affected by the high-quality day care seems impossible. Calculating costs and benefits for this unknown number of people therefore can’t be done. And, in fact, Heckman and colleagues didn’t include all the known benefits. For example, people who had been in the high-quality program were less likely to smoke, providing difficult-to-calculate benefits both for the individual in question and for untold numbers of other people, including those of us who pay higher insurance premiums because of the need to treat smoking-related diseases. Monetary costs to the victims of crime were reckoned in dollar terms only; costs for pain and suffering were apparently not calculated.

Finally, how do we assign a value to the increased self-esteem of the people who had been in the program? Or the greater satisfaction they gave to other people in their lives?

Plenty of unknowns here. But Heckman and his colleagues assigned a value to the program anyway. They calculated the benefit-to-cost ratio as 8.74. Nearly nine dollars returned for every dollar spent. This is an awfully precise figure for an analysis with so many loose ends and guesstimates. I trust that in the future you’ll take such analyses by economists with a grain of salt.

But though the results of the cost-benefit analysis are a convenient fiction, was the exercise pointless? Not at all. Because we now get to the final stage of sensitivity analysis. We know that many of the numbers are dubious in the extreme. But suppose the estimate of the cost of crimes avoided is exaggerated by a factor of ten. The net benefit remains positive. More important still, Heckman and company left out many benefits either because they were not known or because it’s so manifestly pointless to try to estimate their monetary value or probability.

Since there are no known significant costs other than those in Table 2, and it’s only benefits that we’re missing, we know that the high-quality day care program was a success and a great bargain. Moreover, the point of conducting the cost-benefit analysis was an attempt to influence public policy. And, as the saying goes, “In the policy game, some numbers beat no numbers every time.”

When Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, one of his first acts was to declare, over the strong objections of many on the left, that all new regulations issued by the government should be subjected to cost-benefit analysis. The policy has been continued by all subsequent presidents. President Obama ordered that all existing regulations be subjected to cost-benefit analysis. The administrator responsible for carrying out the order claims that the savings to the public have already been enormous.4

How Much Is a Human Life Worth?

Some of the most important decisions that corporations and governments make concern actual human lives. That’s a benefit (or cost) that has to be calculated in some way. But surely we wouldn’t want to calculate the value of a human life?

Actually, no matter how repellent you find the concept, you’re going to have to agree that we must place at least a tacit value on a human life. You would save lives if you put an ambulance on every corner. But you’re not willing to do that, of course. Though the money spent on the ambulances might result in saving perhaps a life or two per week in a medium-size city, the expense would be prohibitive and you wouldn’t then have the resources to provide adequate education or recreational facilities or any other public good, including (nonambulance) health care. But exactly how much education are you willing to sacrifice in order to have a reasonable number of ambulances in a city? We can be explicit or we can be tacit. But whatever decision we reach, we will have placed a value on a human life.

So what is the value of a human life? You may want to shop among government agencies for the answer.5 The Food and Drug Administration valued a life in 2010, apparently arbitrarily, at $7.9 million. That represented a jump from two years previously, when the value assigned a life was $5 million. The Department of Transportation figured, also apparently arbitrarily, $6 million.

There are nonarbitrary ways of placing a value on a life. The Environmental Protection Agency values a life at $9.1 million (or rather did in 2008).6 That’s based on the amount of money people are willing to pay to avoid certain risks, and on how much extra money companies pay their workers to get them to take additional risks.7 Another way of estimating the value of a life is to see how much we actually pay to save the life of a particular human. Economists at the Stanford Graduate School of Business made this calculation based on how much we pay for kidney dialysis.8 Hundreds of thousands of people are alive at any one time who would be dead were it not for kidney dialysis treatments. The investigators determined that a year of “quality adjusted life” costs $129,000 for people in dialysis, so we infer that society places a value of $129,000 on people’s quality-adjusted lives. (The quality adjustment is based on a reckoning that a year in a dialysis patient’s life, which isn’t all that enjoyable, is on average worth only half what an unimpaired year of life is worth. Dementia and other disabilities are more common for dialysis patients than for people of the same age who are not on dialysis.) The dialysis-based analysis puts a human life of fifty years as being worth $12.9 million ($129,000 × 2 × 50).

Economists call values derived in these particular nonarbitrary ways revealed preferences. The value of something is revealed by what people are willing to pay for it—as opposed to what they say they would pay, which can be very different. Verbal reports about preferences can be self-contradictory as well as hard to justify. Randomly selected people say they would spend about as much to save two thousand birds from suffering due to oil damage as other randomly selected people say they would spend to save two hundred thousand of the same birds.9 Apparently people have a budget for oil-endangered birds that they won’t exceed no matter how many are saved!

The great majority of developed nations have hit upon $50,000 as the value of a quality-adjusted year of human life for the purposes of public or private insurance payment for a given medical procedure. That figure is based on no scientific determination. It just seems to be what most people consider reasonable. The $50,000 figure means that these countries would pay for a medical procedure costing $500,000 if it was to save the life of an otherwise healthy seventy-five-year-old with a life expectancy of ten years. But not $600,000 (or $500,001 for that matter). Countries would pay up to $4 million to save the life of a five-year-old with a life expectancy of eighty-five. (The United States doesn’t have an agreed-upon value of a life for purposes of insurance coverage—yet—though opinion polls show that the great majority of people are at least somewhat comfortable with calculations of that sort.)

But how about the life of someone from a less developed nation, say Bangladesh or Tanzania? Those countries are not as rich as the developed countries, but surely we wouldn’t want to say that the lives of their citizens are worth less than ours.

Actually, we do say that. Intergovernmental agencies calculate that the value of a citizen of a developed country is greater than that of a citizen of a developing country. (On the other hand, this practice does have its benign aspects from the standpoint of the citizens of less developed nations. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assumes that a developed nation can pay fifteen times as much as a developing nation to avert a death due to climate change.)

I trust that by now you’re dubious about techniques for calculating the value of a human life. And I haven’t even started to regale you with stories such as those about the insurance companies that pay less for the life of a coal miner than for the life of an office worker on the grounds that the coal miner’s value on his life is revealed to be lower because of his choice of a hazardous occupation! Or the report that the Ford Motor Company decided not to have a recall of its Pintos to put a safer gas tank in the cars because the recall would have cost the company $147 million, versus a mere $45 million for payments for wrongful deaths!

But … we really do have to have some base value for a human life. Otherwise we risk spending large amounts of money to carry out some regulation resulting in a trivial increase in the number of quality years of human life while failing to spend a modest amount of money to increase the number of quality years of human life by hundreds of thousands.

The Tragedy of the Commons

A problem for cost-benefit theory is that my benefit can be your cost. Consider the well-known tragedy of the commons.10 There is a pasture that is available to everyone. Each shepherd will want to keep as many sheep in the pasture as possible. But if everyone increases the number of sheep in the pasture, at some point overgrazing occurs, risking everyone’s livelihood. The problem—the tragedy—is that for each individual shepherd the gain of adding one sheep is equal to +1, but the contribution to degradation of the commons is only a fraction of −1 (minus one divided by the number of shepherds who share the pasture). My pursuit of my self-interest combined with everyone else’s pursuit of their self-interest results in ruin for us all.

Enter government, either self-organized by the affected parties themselves or imposed by an external agent. The shepherds must agree to limit the number of sheep each is allowed, or a government of some kind must establish the limits.

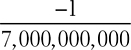

Pollution creates a similar tragedy of the commons. I greatly enjoy my plane travel, my air-conditioning, and my automobile trips. But this makes everyone’s environment more dangerous and unpleasant by increasing the pollutants in the air and ultimately by changing the climate of the earth in potentially disastrous ways. These negative externalities, as economists refer to them, harm everyone on the planet. I am hurt by the pollution and climate change, too, of course. But my guilty pleasures have a summed value of +1 for me and the costs for me are

Self-governing of the 7 billion of us is out of the question at the level of the individual. “Self-government” at the level of the community of nations is the only form possible.

The idea of cost-benefit analysis dealt with throughout this chapter is not a novel concept to anyone. It’s clear that we’ve been doing something like it all our lives. There are some implications of cost-benefit theory, however, that are not at all obvious. Some of those have been presented in this chapter. As you’ll see in the next chapter, we can have several kinds of less than optimal outcomes because of our failure to recognize and apply some nonobvious implications of cost-benefit theory.

Summing Up

Microeconomists are not agreed on just how it is that people make decisions or how they should make them. They do agree, however, that cost-benefit analysis of some kind is what people normally do, and should do.

The more important and complicated the decision, the more important it is to do such an analysis. And the more important and complicated the decision is, the more sensible it is to throw the analysis away once it’s done.

Even an obviously flawed cost-benefit analysis can sometimes show in high relief what the decision must be. A sensitivity analysis might show that the range of possible values for particular costs or benefits is enormous, but a particular decision could still be clearly indicated as the wisest. Nevertheless, have a salt cellar handy when an economist offers you the results of a cost-benefit analysis.

There is no fully adequate metric for costs and benefits, but it’s usually necessary to compare them anyway. Unsatisfactory as it is, money is frequently the only practical metric available.

Calculations of the value of a human life are repellent and sometimes grossly misused, but they are often necessary nonetheless in order to make sensible policy decisions. Otherwise we risk spending great resources to save a few lives or fail to spend modest resources to save many lives.

Tragedies of the commons, where my gain creates negative externalities for you, typically require binding and enforceable intervention. This may be by common agreement among the affected parties or by local, national, or international agencies.