My name is spelt wrong, so what chance did I have? Really, my parents were asking for a dyslexic child. And they did it on purpose. My father hadn’t got pissed before he went down the baby registry and then forgot what name they’d decided. It’s not that there’s an ink smudge on the birth certificate and that now has metamorphosed into my name. No, it was an active decision that my name should be spelt wrong.

Kaiya is usually spelt K-A-Y-A (according to Bob Marley), but my young hippy parents (see: naming your child after a Bob Marley song) weren’t so sure that the numerology of the original spelling was quite good enough for their first progeny. Numerology is a way of placing numerical values on letters which can then be simplified down to a value between one and nine and thus divining what sort of person you might be in the future. Adding an ‘i’ realigned my stars and gave me a better personality. It made sure I was the sweet baby child I turned out to be. Without that ‘i’, the doctor who delivered me wouldn’t have proclaimed I was the most beautiful newborn he’d ever seen (not bragging – just what happened). Without the ‘i’, I wouldn’t have been the toddler that demanded cups of tea upon waking up every morning. I always slept between my parents and started each day with a cup of sweet milky tea in a little mug with The Lowly Worm on. It was chipped and reassembled and glued because I managed to drop it but was uninterested in any other china. Without the ‘i’, I wouldn’t have insisted that my hair, too, should be shaved off when my dad cut off his Jesus locks and my mum decided to rock the skinhead. They’re not spiritual nuts, I swear, despite the head shaving and the occasional kaftan. But as my mum says about the whole numerology thing: why risk it?

The surname Stone is significant too. My parents both have maiden names which means that when they got married they both changed their surnames. Very progressive, I know. They only got married because they wanted money from their parents to go travelling. They did the deed in Wandsworth, the epicentre of romance, and no members of their families were present. So it made it less awkward when they decided to scrap their surnames – Slater and Aldridge.

They had chosen to start again: new family; new name. My mum, not concerned with the years of schoolchildren shouting Wilmaaaa, mimicking Fred Flintstone, saw no potential issues with the new name Stone. The real crime is, of course, that they missed the opportunity to smash their two surnames together and begin the new dynasty. Long live the Slaldridges!

Instead, the Stone family came into being on 3 September 1992 after they picked a new name out of a hat. I like to think they picked it in allusion to the funk kings (Sly and the Family Stone) and British icons (the Stone Roses and the Rolling Stones).

I’m fairly certain that had I been Kaya Slaldridge, I’d be able to spell, play a musical instrument and hold down a real job. Kaya Slaldridge would have met a lovely boy, maybe called Timothy King, and she’d have had a white wedding and changed her surname. She’d smile politely while everyone joked that she should start her own canoeing business. One day she would have snapped, aged fifty-two, and kicked the dog in front of the family. Her children would look at her in disgust and she would go and sit in the pantry and wonder why, oh why, hadn’t her parents just put a little ‘i’ into her name. Then maybe, Kaya Slaldridge would wonder, could I have been a little more selfish?

But, alas, the power of names has spoken and I am Kaiya Stone. For that I can only apologise.

And I was an accident. My parents, in their early twenties, had headed off to India, their pockets filled with cash that their own parents would have preferred to have been spent on a ceremony and subpar buffet. Instead, my mum splashed out on some prescription sunglasses so she could finally see and they headed across the world for a year of adventure. Before leaving, Wilma Stone wished to the universe that the trip would change her life. Three months later, she was pregnant with me – not exactly what she had meant. Yet it certainly changed their lives. They had to come back to the UK and as they did my mum swore that having children wouldn’t stop her travelling. But really, who aged twenty-two and twenty-four is ready to look after another adult in a long-term relationship commitment, let alone be wholly responsible for a baby?

I’m twenty-six now and I baulk at the idea of this level of obligation, of dedication for another. It’s a small miracle that I’m childless, not because I’m having lots of unprotected sex with men, but because I’m the first generation of women in my family on both sides to still be childless at this ripe old age. Maybe we’re very fertile, irresponsible or, more likely, Sex-Ed left much to be desired for many young people. My dad was conceived when my Granny Jayne, aged sixteen, lost her virginity in a shuffle in a tent. She once told me she didn’t even know she was having sex, which is the most scathing post-coital review I’ve ever heard.

So, I guess my conception was not completely out of the blue. Remember, use a condom, kids, else you might have to end your year-long honeymoon really early, return home and spend your early twenties living in poverty as you scrape together nappy money with loose change from down the back of the sofa.

I was born with my eyes open. I think that’s quite symbolic and, more than that, terrifying. I think labour was horrible. I don’t remember it but I definitely have lots of residual trauma from being squeezed out of the birthing canal. I know it must have been really horrific for my mother because she had her own mum there. That’s who told me I was born with my eyes open. The midwife must have had to hide her horror as I slid out wide-eyed and flipping her the Vs.

From the very beginning, the three of us were a team. I slept on my dad’s chest or in the middle of the bed between the pair of them. It gave me great access to tit, something that I still try to maintain in adult life. I have heard that apparently sharing a bed is very dangerous for babies, but I must say I have the most healthy attachment issues of all my friends and I credit this to having breast milk on demand. And this is why I am an entirely functional adult with absolutely no co-dependency issues at all.

My parents’ main childrearing technique was to do the opposite of their own upbringings and to build their lives around what I needed, which is pretty fucking radical. They have always built castles around me, have surrendered any of their own ambitions for my wellbeing and fanned the fire in my chest. My parents were always around, poor but always present. In my child’s eyes they were never not making: art, clothes, food, change. I was surrounded by the potency of truthful creation. Dad was writing novels, being put on waiting lists only to remain unpublished. Mum was tackling generational trauma and the legal system (an important story for another, but soon approaching, time). But, ultimately, they were young fighting artists on the dole with a tiny baby. It’s not romantic, it’s shit. They had no clue but they were just trying their best.

They have never insisted I call them ‘Mum’ and ‘Dad’, in fact it is very odd typing this out, referring to them as what feels like their drag names. To me, they are Wizzy and Adoo, affectionate bastardisations of their names.

I was raised in a bubble of alternative parenting. For example, as stoners, Wizzy and Adoo were fond of a soap opera. All the classics: EastEnders, Corrie, Neighbours. But when they realised that my tiny baby brain was in fact just a sponge and they caught me singing along with the classic intro music to Coronation Street before I could even speak, they jettisoned the telly straight out of my life. I would remain TV-less until my third year of university, where I discovered a passion for shit telly. These days, Pointless followed by The Simpsons on a weekday feels like I’m catching up on missed hours. Nothing makes me happier than a short sharp shock of a reality dating show. It reminds me that most people are stuck in loveless relationships of convenience just wanting to get to the ‘happiest day of their life’ as quick as they can so they can stop trying and slide into the abyss of FOREVER with a man named Dave. But then again, I am a hopeless romantic.

But without telly how on earth does one parent? Their solution was the introduction of the most important institution of my life: the Library. Twice a week my mum would go with me and we would pick a pile of books to read. This tradition continued through my entire childhood.

Much to their horror, I was a big fan of princesses and pink. When I started preschool, they let me pick my own lunchbox. Barbie. Are you sure? they asked. Wouldn’t you prefer this cool robot one, or one with a puppy, or this one with a lady scientist who runs a feminist mobile library in her spare time? Nope, my heart was set on the pink and sparkly. Now, my parents keep their word. Not once in my memory have they ever let me down or lied to me (or they’re excellent at hypnosis and I have no recollection of a myriad of traumatic disappointments), so they got me the lunchbox. But when we got home, we all sat round putting stickers over Barbie’s petite sculpted body with her pointy breasts and little stumpy feet. Everyone was happy and much to their relief I grew out of pink and glitter.

I was involved in all aspects of family living. We all had dinner together, slept in the same room and shared baths. They really pushed this ethos when they let me decide whether or not I wanted to remain an only child. I was keen to play the part of big sister, a role I have worn with righteous pride since they asked me the question. Obviously, I was not involved in the actual creation of my little brother – but I was there at his birth.

Casius Stone was a home birth. I was supposed to be too, but after thirty hours of labour my mum, never one to refuse drugs, had opted (read: demanded loudly) to go to hospital and have an epidural. Second time round, the hippy home birth was successful. While my mum was panting and doing all the hard work on the living room floor, Adoo and I were lying in bed waiting. The red numbers on the digital clock/radio glowed in the dark while we lay listening to Classic FM. That night was so exciting and it’s my earliest memory. Everything earlier than this is mythology. All the other things are stories I’ve been told and heard for many years. But that moment of anticipation is my first twinkling of consciousness. Although I was two and a half, I knew that everything was about to change and it would be a great thing, plus I would get to be a big sister. I knew I would love him and I did.

I cut Casius’s umbilical cord. With hindsight, I’m not sure how responsible it is letting a two-and-a-half-year-old scissor their way through sinew, but luckily the leg grew back. Later, I sat on the sofa in my pyjamas holding Cas, staring at the squished pinkness. It struck me, a thought of ‘this-is-the-most-important-thing-in-the-world-and-I-will-die-for-this-baby’, which is pretty intense, especially for a toddler. But I am nothing if not consistent.

So then there was four, like the Beatles except two of us were children and there was only slightly less sitar. We had been living in Brighton when things began to change. Wizzy wanted to travel and go somewhere new. And my dad’s book was dropped off the waiting list so the big break he’d been waiting for went up in smoke. He had to get a Proper Job™. My mum had an uncle and aunt in Cape Town and my dad got a position in advertising over there. So the fab four were going on tour.

I had been raring to get to school from the very beginning of my existence. My granny had got me an elasticated school tie that I would wear as a permanent accessory. I would longingly stare at older kids in the playgrounds of the schools we would pass on the way to Iceland to pick up frozen mince. So when we arrived in Cape Town, I was hyped to start at my first educational institution.

My parents, of course, picked out the school in Cape Town with the same values they had raised me with. It was about as alternative as you would expect for any place called the Children’s Studio. It was a very traditional Montessori school, which means mixed-age classes, lots of creativity and a super-liberal schooling system. Everything was taught via the means of sand, pouring and cuddling trees. It was the sort of school where you called the teachers by their first names. Wizzy had looked round when we first arrived in the country and saw these wax crayon and food colouring paintings done by the kids, a signature style overseen by the wondrous Alex Mamacos (who would go on to be a beloved family friend). She decided that’s the sort of school she wanted to send her kids to.

There weren’t huge numbers of rules at the Children’s Studio – just the usual love and kindness ones. They were fascists for peace and understanding. Oh, and you weren’t allowed to play as characters from TV or film. So if you were caught pretending to be Spiderman or a Disney Princess, you would be told off for not having enough imagination because we ought to be inventing our own characters. I liked this rule because we didn’t have a telly so it meant I didn’t have to fake knowledge on the current affairs in cartoons. The other kids would quietly try to play superheroes or Power Rangers. But the pew-pewing and singing of theme tunes tended to give them away. Occasionally some young Einstein would claim that they were in fact playing the book version of Inspector Gadget. Ingenious.

At school, we traded songs. I taught them the rainbow song (which is fundamentally flawed because have you ever drawn a rainbow out in the order red and yellow and pink and green? – rank) and in exchange they taught me political chants. My body’s my body, nobody’s body but mine, you’ve got your own body so let me have mine.

My school was full of kids from all sorts of backgrounds and there were other international children too. My best friend was Thandiwe, or P as she was known back then. Her mum, Alex, was best friends with my parents and not just because of the paintings. We all went up to this house Alex’s family owned in the middle of nowhere, De Tois Kluff. On the drive up, there were herds of wild zebra. At the house, there was no electricity or plumbing but a full collection of Asterix books. Me, Thandi and Cas played for hours in the river naked. My other friend in school was a Spanish girl whose parents were doctors and her baby brother I thought was called Avocado (now I realise his name must have been Ricardo). I watched her do flamenco in awe with her tiny castanets. All these little childhood interactions made me realise how much breadth there could be in people’s existences.

I remember a lot of this time even though some of my friends say they can’t remember anything until they were about nine. We’d moved country in 1997 when I was four and this new home felt very different from Leeds and windy Brighton where we had been living before. The things that I remember sound like the made-up imaginings of a seven-year-old but were a normal part of life in Cape Town. I remember the dassies, these little mountain dwelling rodent-y things that pooed Maltesers. Or the penguins sprayed pink that lived on the beach even when the sun was beating down. The Cape Town we arrived in was at a time of hope – Madiba was president. As far as possible for a little kid, I knew about apartheid but it was hard to see whether it had really ended. Perhaps because it was new, I couldn’t help but see how glaringly obvious the divide was. Children are preoccupied with fairness and I was certain that this was not fair. There were two types of houses: the fortresses with bars on the windows and doors and guard dogs that were racist; or the patchwork houses made of metal and cardboard lining the motorways. Wealth and poverty sliced up this new country.

We lived in a bungalow, which felt exotic for its lack of stairs. The garden had a tree with a platform built onto it, we had two cats that used to visit us, it even had its own little playground and you could see Table Mountain from the kitchen window. There was a big wall which I could climb and there was a boy my age who lived on the other side who was my friend. Well, he was, until his parents caught my brother chasing me with a knife one morning when my parents had been out of the room for a moment. But the real nail in the coffin for the relationship was my parents catching his dad using the n word.

Part of the reason the Cape Town chapter of my childhood felt like it was full of imaginings was because I’d moved halfway round the world but also it was because everyone around me was making literal magic happen. At school, there was this weekly cake raffle where every Friday a name would be pulled out of a hat and you got to take home a cake. Then the next week you’d have to bring in the prize cake. To me the only lottery worth winning involves taking home a cake. I pulled out the dream ticket twice, and the best bit was always getting to make the next prize and feeling proud when people really wanted to win it.

The first masterpiece that my mum and I made (mainly her) was a swiss-roll steam train. She bought the cake pre-made and we covered the whole thing in twinkly Jelly Tot jewels. There were chocolate button rivets and Kit Kat pistons. I don’t want to blow our own trumpet but it was a feat of edible engineering and parental ingeniousness that involved zero baking and maximum effect. I remember everyone, including my little brother, looking in wonder at this cake as I processed it in on the Friday morning and placed it in the school kitchen to await the Fates to allocate who would get to be the proud owner of such a treat.

Wizzy got a phone call from the school that afternoon. Casius, all angelic with his golden curls, had snuck into the kitchen somehow, presumably SAS-style, shuffling under the shutter. He’d pulled a chair to the table and climbed up. Now, here was the truly ingenious bit. He had eaten the front cylinder of the choccy locomotive, managing to leave the back untouched. But to ensure he wasn’t caught, he didn’t use his hands. Instead, he must have laid on his belly and chomped away like a snake disguised as a cherub. After gorging on the prize, he settled down to hibernate like any full predator would. A teacher found him napping, I’m presuming with an angelic smile on his cakey mouth, on the table. This was the fatal flaw in his otherwise perfectly executed crime. Wizzy had to go into school, chop the driver’s carriage down a bit, whack on a few more sweets, and no one was any the wiser. Cas had gotten to eat the cake he’d seen being made in our kitchen and I got to still give the raffle winner the best cake ever made, albeit a bit shorter than it had been.

This is pretty symbolic of my whole time in Cape Town: weird traditions and free-flowing kindness. My wild-eyed brother wasn’t told off because he wasn’t naughty, he was excited and no harm was done. I wasn’t bothered because it didn’t matter and I thought Cas was funny and he was my little brother. For the sake of the narrative arc, I see these as the idyllic years of my childhood; a time where I mostly believed anything was possible.

One morning, I woke up and told everyone it was my birthday on a day that was not in any way my birthday. I played birthdays in the garden and made myself a cake in the sandpit we had. Then Cas and I played some proto-computer games. Ones where we clicked on illustrations and little Easter-egg animations would jump up and sing ‘Dem bones’. While we were immersed in the most advanced feats of child entertainment, my parents went to work. After the gaming session, Cas and I left my dad’s computer to find a birthday party. Wizzy and Adoo had baked me a real cake and strung up balloons. We all sang happy birthday. Miracles happened and the world felt magic.

In this magic world I was taught the most important thing a child can learn – to love yourself. It sounds cheesy but it’s something that I can’t help be incredibly thankful for. I was at a school where I was told I was great and I had parents who were fun and loving. I didn’t know what would happen in the world, I certainly knew that society was unfair and cruel, but I also knew that unexpected unimaginable wonderful things happened too. I learnt to be kind to myself and others.

At this point, I also began to have my first understandings of mortality and began to obsessively worry about death. More specifically, I became obsessed with suffocating on my own tongue. Something had clicked in my head and I realised that I could die at any moment, life was fragile. I had, however, pinpointed the most likely cause of my death – my traitorous little tongue. I was often found holding onto it in case that little bit of skin snapped and my wet pink mouth muscle wriggled down my throat. The fear of mortality had manifested and has sat with me ever since.

I’m still pretty existential. There is a tension between the confident, cocky and joyful Kaiya and the parts of me who are terrified and full of doubt. I have these waves of panic and worry. I lie in bed and feel so tiny and startled by the enormity of being alive. It’s a very specific fear – it stems from wondering why can we think? What is the point of being alive when we will so quickly, certainly and suddenly disappear forever? Even as a tiny child, I had some innate understanding that this was ‘it’, there was no heaven, there was no afterwards, just the right here and the right now. That is a lot of quite heavy and weighty thoughts for a five-year-old, it’s a lot for a twenty-six-year-old. So, to deal with all of that I just held my tongue (literally).

My parents tried to soothe my anxious mind. They assured me that only people with epilepsy could swallow their tongues.

But maybe I have epilepsy?

No you don’t. You’d know.

What is epilepsy?

It’s when you shake and have fits. Sometimes it’s triggered by flashing lights.

After that conversation, I became worried about blinking too quick in the light in case that caused me to see flashing lights. At Christmas we went round the shops to get food for the traditional big turkey dinner. I bit firmly onto my tongue all the way round the South African equivalent of Tesco. My granny, who had come over to visit and must have been freaking out that her granddaughter had changed quite drastically with the move halfway across the world, kept asking me why I was holding my tongue, which is not something I have ever been good at in the metaphorical sense. I couldn’t get her to understand that if I stopped I risked certain death. I was not going to fall into the trap of unclenching my teeth to explain and then the bit of skin would snap and then I’d choke and die and Granny wouldn’t be very happy after that, would she? Christmas would be ruined.1

All the neuroses cumulated into one big incident, when I woke up and I was trembling – like little shivers in my hands. Tiny tremors. The more I panicked the bigger I shook. I ran into my parents’ bedroom screaming that I was swallowing my tongue and desperately trying to keep a hold of it while speaking. They sat me down and finally explained that epilepsy wasn’t something that just happens. After that morning, I stopped holding my tongue but the chasm of consciousness remains a source of great discomfort. I cannot forget that this will all end soon. (Note to self: fridge magnet idea, Life is Loss.)

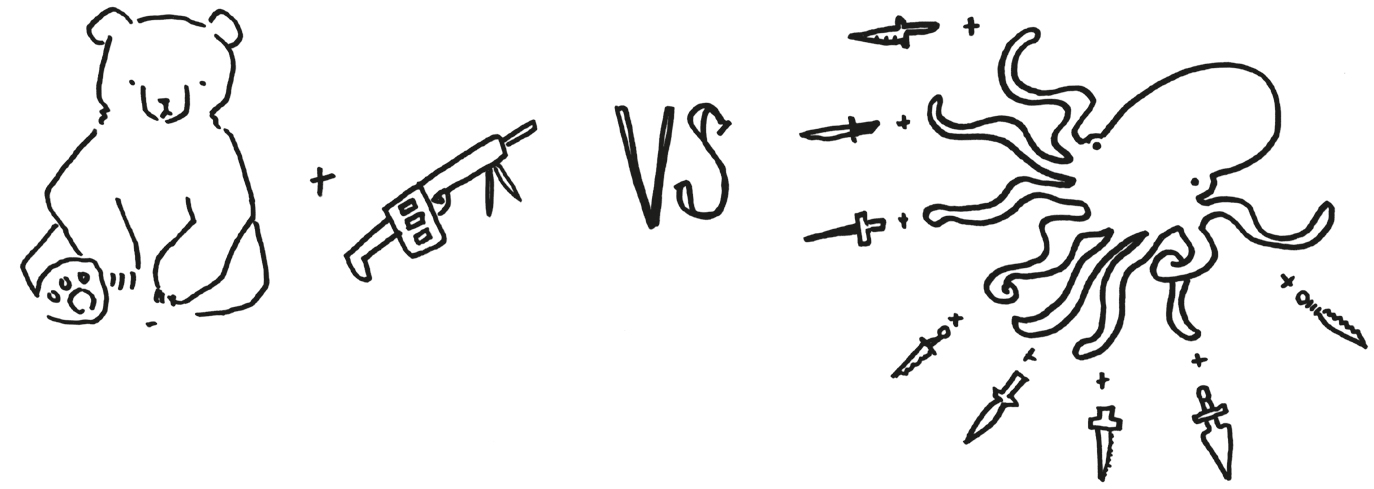

Something that coincided with all this was that I kept asking what the meaning of life was. I’m sure my parents were wishing I would ask what most six-year-olds ask: things like who would win in a fight between a bear with a machine gun or an octopus with eight throwing daggers. The answer they always gave was love, and I was like – yeah, duh.

One day I managed to get an alternative response. We had a treasure hunt with our friends Alex and Thandiwe in the woods where I found this little doll. Her little embroidered face seemed so real, but did she have consciousness? I could imagine an inner world for her but that was from my brain. All evidence pointed that she was an inanimate object. Why wasn’t I an inanimate object? Why could I even think of such a terrifying question? This triggered my penchant for philosophy once more and I asked again what the meaning of life was. The adults looked at each other and began to discuss all the potential answers. After a couple of minutes they agreed on an Official Line: the most important thing to know was to know who you are. Again, I was pretty certain I had that one worked out. I was Kaiya Stone and I loved lots, so I’d got life sorted and as long as I didn’t choke on my tongue, I’d be fine. I wish I was still this certain.

1 Apparently my granny didn’t visit us in South Africa, so I think I must have relocated this incident to a different country, but the memory still stands. Sorry for being an unreliable narrator. Try not to be too gullible.