Something odd happened in my first parents’ evening at Batley Grammar. For some reason, the school asked the Year 7s not to attend, so my parents went off in their jeans and trainers to meet all my teachers. It must be a horrible time warp to leave school in a fury, swearing blind that you’ll never set foot in an institution like that again, only to find yourself returning via your spawn. In that first parents’ evening, my physics teacher told my parents that I was special and that I was Oxbridge material. This man had never indicated to me that he thought I was anything out of the ordinary, which is probably for the best – it would have gone to my head. I was already at risk of being insufferable. I was surfing the mixed messages being sent my way, which resulted in the constant oscillation of extreme self-confidence and painful self-doubt. I clung to any tiny piece of affirmation and metaphorically pinned it above my bed – much like your recently divorced aunt does on Facebook.

I have always imagined that this was a throwaway comment that got out of hand.

But my parents returned home and repeated that phrase Oxbridge material to me. It meant no more to me aged eleven than it did to my parents. We had to work out that it wasn’t one place but two very old universities that seemed to have some sort of mystic power thus deserving its own term. This lack of knowledge was not some momentary lapse but a chasm. It was just the edge and the glimpse into a different world. My mum googled it and took it to mean I should be aiming for the best, a thought already in their heads but without the vocabulary of academic success. Mr Miller sat with us and set me on a particular track. I was impressed and my parents were impressed, because neither of them had a degree, or even A-levels, at that point. So for every snide comment from one teacher, there was the constant internal rebuttal. Someone had said I was going to be a writer, another teacher said I was Oxbridge material, and my parents say I’m bound for greatness (thanks for the achievable goals). I chose to believe the good stuff. How else was I supposed to survive?

Now, the fun bit, I get to write about the teachers who waved my flag, wore my colours and made up chants on the sideline of my symbolic sports match. The greatest thing about my school was that we had a classics department. By that I mean a bulwark of a woman who single-handedly kept this very niche subject alive. Classics is the study of ancient civilisations, their history, art and literature. In the past, my school also taught Latin and Greek but it had fallen out of fashion. The head of classics kept the subject afloat by teaching the subject in English (classical civilisations) and by consistently getting the best GCSE and A-level grades of any subject in the school. It was by far the most popular humanities subject for A-level.

Mrs Wilson was a petite woman coming up to retirement. If I were to guess, she was almost certainly an Autumn, in Colour Me Beautiful terms. No one could rock a burnt umber silk scarf better than her. Despite her slight frame, everyone, pupils and teachers alike, were terrified of her.

There is something special about a strict authority figure, and I say this as someone who is not a big fan of power hierarchies. It just seemed to me that the teachers who were the harshest were in most ways the fairest. They had sometimes ridiculous arbitrary rules but they were honest about the consequences – if you do X, Y will happen. But you have to give very clear instructions to enforce such a world, and I think that suits me. I have also always found that the strictest teachers are the most compassionate and generous with extra help. Plus, with my two favourite teachers (Mrs Wilson and Mr Hussain), their strictness was always about getting the most out of us. Funnily enough, the scariest, strictest teachers in my experience never shamed me. They lifted me up.

Classics was a revelation for me. I had never been the sort of child who was really into myths, partly because I had never been taught them in primary school. But what is not to love about stories about gods that behave badly, mythical creatures and heroes. As we moved through the years, the topics expanded. We looked at the history and started reading original literature (in translation) and I realised that it had all of the things I loved. It was an expansive subject and my enthusiasm was only encouraged. When we read photocopied sections of Ovid’s Amores – which is a bit like an ancient love advice column – Mrs Wilson lent me her copy of the whole book. She handed it to me saying to watch out for the saucy bits. Aged fourteen, all I wanted was ancient writings with double entendres and adults winking at the bits of the world that I was starting to step into.

Plus, Mrs Wilson’s lessons were fun. They always involved drawing and re-telling stories or looking at ancient artefacts. In some ways, as I got older I wondered if it was too easy or too childish. Especially when teachers had begun to talk darkly about GCSEs and university and academic achievement. In other subjects, things were desolately serious and all about answers and techniques. But in Mrs Wilson’s classroom, the coloured pencils were always out. With hindsight that’s perhaps why I loved it. It was freeing and it appealed to my love of education rather than the oppressive system of grade-marking, levels and grammar that dominated lots of my other lessons. More than just that, Mrs Wilson took it deadly seriously. Here was this woman who could silence a room full of fighting sixteen-year-olds with one look and she was getting excited about the sort of magical herb Hermes gave Odysseus to prevent Circe turning him into a pig (it’s moly, if you’re interested or inordinately worried about turning into a pig).

That passion is contagious. When I decided in Year 9 that classics was going to be my thing, other teachers sort of suggested it was a waste. A PE teacher pointed out with my grades I could be a pharmacist, the height of the school’s ambitions. But I didn’t want to think about getting a job or careers. I had absolutely no ambition to do anything remotely sensible like law or medicine. I just wanted to leave Batley as quick as I could and by any means necessary.

There was a funny club that one French teacher set up called Culture Vultures. We went to musicals, ballets and occasionally obscure opera for cheap because of school group tickets. My parents knew they could never afford to take me and Cas to these sorts of things as a family but they made sure I could go with Mr Wilby’s group. I never missed a show and so when the original National Tour of The History Boys made its way to Sheffield, he let me go despite its adult content. It was one of the few times in my life that I saw something of myself reflected on the stage. It felt like I’d been hit by a bag of pianos when Posner said: I’m Jewish, I’m small, I’m a homosexual and I’m from Sheffield. I’m fucked. It’s only two out of five for me, but it felt closer than anything else I had encountered before. It was all I could think about for the coming weeks. I felt a kinship with Alan Bennett and being an outsider in my little corner of Yorkshire. I’d not ever thought about the possibility of being queer because it wasn’t an option. So much of it was subconscious recognition but it rang a bell loud within me. It connected that throwaway comment from the physics teacher to this world of thinking differently and arguing and education as something other than marks out of ten.

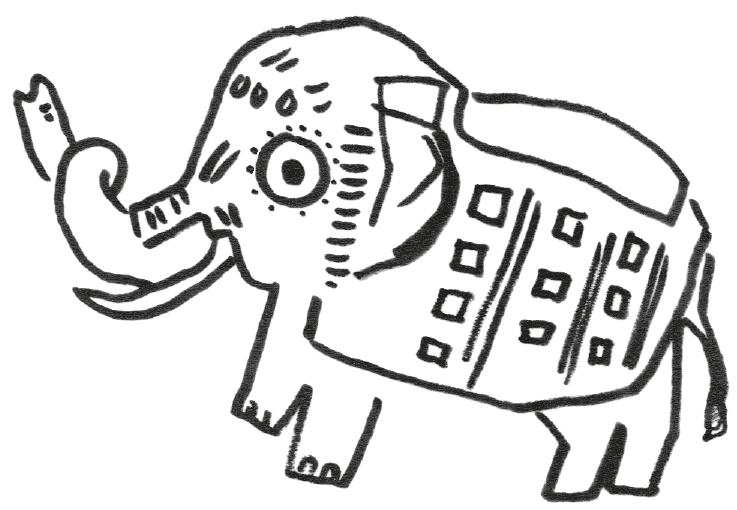

I think it is important to note that I did, albeit briefly, do all the usual British teenage things. I had dabbled in being an emo – the subcultural chic of the early noughties. But I didn’t want to dye my hair black nor did I have the money for the required minimum three studded belts. This period of time coincided with my trips to Leeds on a Saturday. We would hang out with the other usually much older teenagers who also wore all black. We’d spend hours chatting on MSN and redesigning our Myspace pages, only to meet in person and stand in awkward silence and then head to Greggs for a sausage, cheese and bean pasty. There weren’t many of us who did this from my school and so I was able to build a sense of self beyond my classroom experiences. I used to buy the younger-looking teens fags (when you could smoke at sixteen) and aged thirteen I got served for the first time in a Lidl. We sat in a triangle of grass between the motorway and a retail park on the outskirts of the city and five of us shared the two-litre bottle of lukewarm scrumpy. Other days we would endlessly walk around the shops or talk of parties. If it rained, we would walk round the Royal Armouries until we found the Armoured Elephant glistening under the weight of thousands of panels. I always pondered how this creature had ended up here in Leeds with its sad golden eyes like a trunked grim reaper and the faceless riders on his back.

But as I got older things changed. The Corn Exchange was gutted. The owners kicked out all the shops selling sex toys and incense and tried to start a food court. The community of vampiric teens were moved on. I moved on.

The introduction of wireless internet had already transformed the world as we knew it. When we replaced our babbling modem, it brought about a profound change for my household. It meant the free and easy access to information. My dad continued to put his work up online (always an early adopter) and an online zine he made got some real traction. He got a literary agent and eventually his first book deal. But it was Wilma Stone who really took it by the horns. She decided to do a degree at the local art school. She worked very hard to get in and continued grafting through the course. A fellow student’s younger brother had got into Oxford. My mum relayed the information that he used to wake up every day at 6 a.m. before school to revise for his A-levels. We took this information as gospel and so, as I entered into Year 11, I began getting up before even the sun had crawled up.

My parents took it in turns to wake up with me and make me a coffee as I would work the extra hour before heading to school. When I came home, I had tea with my family and then returned to my desk. It felt normal. My dad worked at home and his desk was along from mine. My mum was learning new skills, filling sketchbooks and reading critical theory for the first time. So all three of us just worked together. It was the living encapsulation of what I had been told growing up – the most important things in life are Family and Work. At weekends, we would watch films in the evenings but there was a lot of productivity in the Stone household.

I never once breathed a word about my early morning work sessions to anyone at school. I was predicted A*s across the board for my GCSEs. I didn’t find the work particularly hard but there was so much of it and it took me a long time to absorb the information. When I went to sit my exams, I went in knowing I was going to do well. On results day, I was satisfied. It sounds odd but I was quietly disappointed that I had dropped a couple of the stars off the As of history and English. Two subjects I had thought were my best.

I had been debating where to go for my A-levels. I was not particularly happy at my small school. There was an excellent sixth form college with 2,000 students around the corner. But it didn’t teach classics. I knew that I could apply for classics without the A-level in the subject because most schools don’t teach it. But I couldn’t imagine spending two years not studying with Mrs Wilson. So I stayed on.

The summer before starting my A-levels, I went to Latin Camp. It was one of the million things my mum had found on the Internet about improving my chances of getting into Oxford. She had quite rightly pointed out that if I went to Oxford to study classics most of the kids would be from posh schools and would have studied at least one of the ancient languages. The Oxford University website assured us that it wouldn’t be an unfair advantage but we thought I’d better find out if I even liked it before I sunk all this time into it. Luckily, there was a wonderful group called the Joint Association of Classics Teachers (JACT) and they ran summer schools for kids who are beginners to Latin and Ancient Greek. Not just that, but they had great scholarships.

When I arrived at Wells Cathedral School, I began to realise that most of the world really was not like Batley. I had suspected it for quite a while but when I looked around the boarding school we were staying in, I really understood that I wasn’t in Kansas any more. I met a lot of posh people for the first time and it was weird. It sort of felt like they were LARPing an Enid Blyton book. They all played the piano and sang in choirs at the little chapels attached to their schools. They had names like Tosca, Boris and Biddie. Lots of them were used to staying in the boarding houses we were put up in with four sets of bunk beds and neatly lined-up desks. More importantly, they had been doing Latin and Greek for at least five years. On the other hand, I did not even know what prep school was.

The first two hours felt horribly intimidating. But as soon as I was put in a beginners’ class, it all changed. We were going to cover four school years of Latin teaching in ten days. I had a great young teacher who brought out all the good stuff about Latin – the sex, wild history and explicit poems. I was in a class with older people, they were all eighteen and about to head to Oxford to study classics. But, like me, they were not from posh schools. It was the first time I’d met people who were accessibly older than me. To me they seemed so clever and cool.

We did our classes and then sat together after working. I hadn’t really ever got to do that before. Work was something I did alone. Jim would improvise songs about us all. Helen was warm and funny. Lorna had planned to do medicine but suddenly changed her mind. Scott had been a postman and was about to start at Oxford as a mature student. Lucy was the same age as me and was just as ambitious. But perhaps more importantly, they saw me differently than anyone else had before. It was at Wells that someone told me that I was funny for the first time in my life. I had never before been funny. My crude, rude comments and asides had been met with evils at school – Why do you have to be such a freak all the time, Kaiya? But here I could make people actually laugh. We sat in the sun and did Latin, eating ice cream, and it felt like the first summer I’d ever had since becoming a teenager.

Another important thing happened as I pushed out through my mid-teens and approached the ending of compulsory education. I started receiving the Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA). The EMA was a Labour government initiative to encourage students to stay in education past GCSEs. It was means-tested and gave the poorest students a weekly allowance dependent on their attendance in their educational institution. I received the largest possible amount of £30 a week. I had never really had a regular amount of money; there was one six-month period of time when I got pocket money but generally I had to ask my parents for a tenner here and there. That, and any birthday and Christmas money, were my teenage income.

But entering into sixth form all that changed. Thirty pounds a week was unimaginable wealth for me. I could buy clothes and makeup and go out for dinner with my mates. While previously I never really felt poor, I was aware of the differing financial worlds my friends and I lived in. My school was filled with kids with either working-class parents who had climbed the social ladder or middle-class aspirationals. Brands were king. Perhaps out of an internal understanding that if I wanted them I couldn’t have the Uggs or the Juicy Couture or the Louis Vuitton handbag, I decided that I was completely uninterested in that world. If I didn’t want much then I couldn’t be disappointed.

For sixth form, my classes shrunk significantly. Even though my class groups were tiny, my teachers just assumed I was fine. They worried about the other kids. There was just an expectation that I worked hard and that would be enough. I thought exactly the same. Mrs Wilson, however, characteristically went the extra mile. She taught me, Daniel Murray and Samuel Paley (another keen kid) Latin GCSE in her spare time. She wanted us to be her last hurrah before retiring.

My other favourite teacher was Mr Hussain. At the time, he was the only Muslim teacher in the school, which was just one reason why he was notable. The second reason was that he was nearly as feared as Mrs Wilson. He stalked corridors and enforced uniform rules draconically. I was terrified of him for the two years he didn’t teach me, but as with all ominous figures I was morbidly fascinated by him. Eventually, he became my history teacher and he remained so until I left school aged seventeen. What was shocking about him was that he was very relaxed in his classroom. He appeared to have the armour of a severe guard in the corridors but in his room he was different. In one of our early classes he tested us – asking what a child born out of wedlock was called. Never one to hold back from testing boundaries and swearing, I piped up. Perhaps everyone else didn’t know, but when I exclaimed Bastard their eyes widened. Some particularly melodramatic girls, with GHD-straight hair, gasped. They eagerly awaited my punishment but it never came. My answer was just met by a knowing smile. I knew from then that we would get on.

In his classroom, debate was king. I am not a fan of devil’s advocate in real life. It is often used as a tool to question people’s lived experience, to try to pretend that the world should be objective. Really objective just means that some old white guy has said something in such a way as to pretend that his opinion has not been informed by his own very limited life view. But I think I learnt more from having my arguments rigorously questioned by Mr Hussain than I ever did with all my other teachers put together. It wasn’t about the facts or simply having information, it was about how you could use it and manipulate it. I guess one could call it critical thinking. One of his favourite things to do was to split the classroom and get us to argue the opposite of what we believed. His least favourite thing was marking, which he didn’t do.

Once in class, Emma Elton asked who the smartest student Mr Hussain had ever taught was.

Daniel Murray.

What – not Kaiya? She looked at me wickedly. I would be lying if I said I wasn’t absolutely gutted. It’s not a competition, but I had lost.

Daniel Murray was in the year above me and in sixth form we became mates. In some ways, we were very similar. He too was obsessed with classics and wanted to study it at university. He was the other kid with a full scholarship but he had to share a bedroom with his two brothers. He used to joke that all of his adult clothes came from a bin bag that a man had given his dad in the pub. It wasn’t a joke. He once showed me the pub. But Mr Hussain was right; Daniel was definitely more clever than me. I was so jealous of his memory and his ability to write things down. We bonded because we both had big aspirations that seemed to be above our stations.

Oxford and Cambridge were not on our school’s horizons. Everyone seemed to go to either Leeds University or Leeds Metropolitan, depending on the grades. But Mrs Wilson drove us both in her own car on a Saturday to Oxford for an open day, and a couple of months later Daniel came with me and my parents to look round Cambridge. I settled on Oxford because I liked the course and it was near London. I wanted to be near a city; I worried about being suffocated by the smallness and the beauty of a town. Daniel picked Cambridge and a college where our deputy headmaster had assured us that they would like us as the college had links to Yorkshire.

This really is the evidence that my school had no idea about Oxbridge. But for Daniel and a few other kids in his year, the senior staff decided that they would try for the first time in decades to get some pupils into Cambridge. When the interviews were offered to a couple of applicants, the headmistress congratulated them in assembly. Off Daniel went to Cambridge. He came back disheartened. He didn’t get in. The chips on our shoulders grew heavier. The following months were awful. He was so depressed. I never had a chance, they don’t want people like us. I was gutted – if anyone deserved it I was sure it was Daniel. I still think that.

But the blow didn’t just affect him; the school took it as a sign. Oxbridge didn’t want anything to do with us. I was told not to apply. My form tutor explicitly said: If Daniel didn’t manage it, why would they want you? It’s a waste of an option.

I feel like there was this very odd attitude that ambition was something to be ashamed of. It feels sewn into the local identity. We tell ourselves that we live in God’s Own Country, that we’re friendlier, better, less poncey than down south. But with that comes the acceptance of not just being the underdog but being the righteous dejected, the martyred denied, the no-winners. Our holiness comes from our lack of ambition. God forbid you show a twinkling of wanting something more: who do you think you are?

By this point, I was the sort of kid who revelled in adversity. I got a lot of strength through defining myself in opposition to the people around me. I don’t actually think I’m better or brighter than anyone else but I definitely got some of my determination from this time, from a belligerent doggedness and desire to prove everyone wrong. I was just the wrong size. I was too much for that world, too big and too loud and I wanted more.

One prime example was when a DT (design and technology) teacher pulled me aside in the corridor between lessons. What’s yer backup plan for when you don’t get into Oxford? I was confused. He explained that he was doing a full school assembly and wanted to use me as an example of why it was important to have an alternative set of goals. He wanted to stand up in front of everyone and say look she’s clever but even she is prepared to not get what she wants. I couldn’t believe it. I was furious. I told him There is no backup plan. He didn’t do the assembly.

This was all well and good but it did mean I had to follow through. I felt the weight of how much I had to prove myself. When you decide that you want to go against the grain and that you want something more, you'd better manage it. Otherwise you become the joke. When I collected my AS results, it was imperative that I got As across the board. There was a general consensus that I did not need to worry. I did all the work. I had continued to wake up at six before school. I felt like I couldn’t fit any more work into the day. It also just so happened that the grades were released on my seventeenth birthday. The only gift I was bothered about was the marks.

It was the first time in my life that I had truly failed. I had managed to do very well in classics but everything else was way off the mark. I couldn’t understand it. I stared at the paper, surrounded by everyone else, panicking. Nobody in my year had done very well. But I had dropped two, three, four grades. I had done everything I possibly could and it wasn’t enough.

My mum had waited in the car. I slammed the door closed and in the confines of the Ford Focus I melted into a state of delirium. I was never going to manage it. I was stupid. I was going to be stuck here for the rest of my life.

The remainder of the summer was a pit. After the initial frenzy, I settled into a heavy cloud. I just didn’t know who I was any more. If I wasn’t a nerd who did well in exams, who was I? I went to a couple of parties and after the last one I was sick in the back of my parents’ car. I had never been so sad. Mum and Dad said we’d make a plan. They put me in bed next to my brother with a bucket. I don’t think Cas slept very well; he kept checking I wasn’t going to choke on my vomit.

Any saying about failure is a wonderful cliché. It never makes the blow any easier. But for me, after that first earth shattering, I learnt that you survive it. I have also since learnt that failures don’t stop coming. Much like hiccups and murders in Poirot, it’s never just the one.

The start of a new school year was a public humiliation, walking in and seeing everyone looking at me. And they knew and cared. This sounds like a high school movie, with our protagonist walking in and everything juddering into slow motion. But in the first week of September, I walked into the sixth-form common room and felt every pair of eyes track me. My school was tiny, we all made it our business to ensure that the limited amount of information was well disseminated. I couldn’t complain that I was the centre of attention because I love gossip. One must accept that sometimes you are the gossip.

But my parents and I had sat down and made the plan. I dropped English – my worst grades (D + E). I would have to re-sit the entirety of history AS and half of my French papers. I would still apply to Oxford. I just had to make sure everything else in my application was so outstandingly good they had to take me seriously. My essays were already solid because they were classics ones. My personal statement was fire. It wove in all the books I had read while focusing on my favourite idea that the greatest thing about classics was that it would be transformed and changed and adapted over and over again. Did it start with a quote? Of course it did, this was 2010 and the old open with a quote had just been invented. I had been writing and redrafting for the last six months. Mr Hussain and Mrs Wilson made sure that I had a great reference.

By some miracle, I did get an invite to interview despite the grades. That is more to do with the fact that not that many people want to study old dead languages and pots. But I did. Prepared to my eyeballs, I reread the books I had mentioned in my application. I packed carefully selected outfits into an old brown leather suitcase I bought myself for the occasion. Like every outsider, I put myself in a uniform. Overdressed, in vintage clothes, Mary Janes and a statement hat, I arrived in Evelyn Waugh-inspired drag.

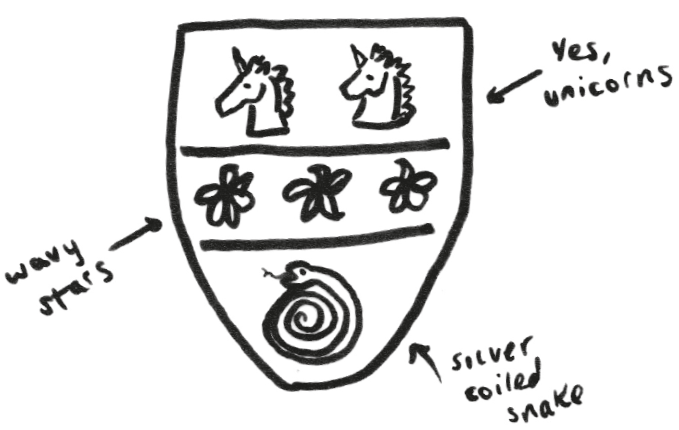

Oxford is made up of colleges, which are bit like houses in Hogwarts. You apply to a college not just the university. I had chosen Magdalen, which is pronounced Maud-lin – my mother warned me ahead of time. The Internet is a wonderful thing. I had decided that if I was going to try to smuggle myself into this university, I might as well heist myself into the most majestic place I could find. Magdalen has its own deer park. That seemed impressive to me, like a posh understated zoo.

I flung the suitcase onto the bed in the room I was staying in. I hung up my clothes. I sat down and practised the breathing technique my mum had found on YouTube. Four seconds in, hold for four seconds, out for six, hold for six and repeat.

Before my first interview, I was shaking like a shitting dog. The breathing helped. I had to be clever and charming and keen. I just needed to be myself. The first interview was with three old white men. I was prepared for all the horror-story questions. You know, what was Augustus’ favourite breakfast? But they didn’t do that at all. It was very kind and a little bit cruel. What do you want to talk about? The one question it had never crossed my mind they might have asked.

I left the first interview very confident. I had made them laugh. I had remembered lots of my reading and, most of all, I enjoyed it. Over the next few days, I had six more interviews at different colleges. None quite as successful as the first. In one, I was asked to put several pieces of ancient pot in chronological order. In another, we talked about grammar. The penultimate one was the worst. I was sent to another college and the tutor was wearing a drug-rug jumper which confused me. He asked me why I thought I deserved to get into Oxford with my grades. I welled up and through hyperventilating breaths tried to explain I’d only had a bad set of exams.

The last interview was at a college I had thought was single sex. It turned out that it had started accepting men, too. I was excited, one of the tutors was the pioneer in modern interpretations of classical works, which was my favourite. I was interviewed by three women on a low sofa. Midway through I had a mind-blank and I could feel them being generous. I thought it was pity.

After it was all done, I called my dad who drove all the way down to Oxford to pick me up. I cried the whole way home. I can’t imagine it was quite the father-daughter road trip he had pictured.

My parents now talk about how they didn’t sleep a lot during this time period. Mum thought it was an early menopause but it was actually stress on my behalf. They were terrified that I wouldn’t manage it. It is hard to have faith in institutions that you have no experience with or that are ultimately exclusionary. I was scared too, but really my parents carried the heaviest burden.

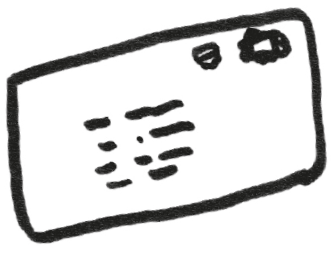

In those days, they tried to let you know about the offers before Christmas. And they did it by letter. It was the last snowy December I remember, and the post was delayed. Other people had been getting their letters, according to forums on the Student Room. We went for a walk as some form of delay and distraction from what felt like impending doom. There was a letter waiting for me on my return. The envelope was stamped with the St Hilda’s crest. That was the college with the women on the sofa. I opened it – an offer dependant on three As. Those three had decided to take a chance on me. We all cried with relief.

I rang the school to let them know. The headmistress told me that I must have misread the letter.

Now it was just the little matter of the grades. My parents found me a history tutor – Tracey. She was a PhD student whose speciality was Disney and fascism. She was bubbly and wore a lot of Mickey Mouse-emblazoned jumpers. She got equally excited talking about the intricacies of the Nazi government and the newest additions to the princesses. To support herself through her studies she worked in the Disney Store in the shopping centre and she came round our house on a Sunday morning. She coached me in exam techniques. I wrote essay plan after essay plan. I realised that I had never before been shown what an essay was supposed to look like. That there were ways of structuring my writing to hit exam criteria. I had always just gone in and tried to write as much information as possible on a page. Now I saw that I had been working hard but not effectively. I hadn’t known there were rules.

I also started getting up even earlier in the morning, this time sneaking in two hours before school. What little social life I had before was put on hold. I promised myself that I could have fun after all this hard work. With or without the grades, I had the rest of my life to go out. Being a teenager is shit anyway, I told myself.

Most of all, I was terribly lonely. I felt isolated from the rest of the world. What few friends I had had gone to university the year before or were far away. I spent a lot of time thinking about the future, taking each individual day at a time. I learnt my dates for history and my French grammar, but mainly I built the foundations of my work ethic. I sewed an ability to be alone into the fabric of who I am. I knew it wouldn’t be like this forever. Things would change.

I took what comfort I could from myths and the classical texts I read – Sappho, especially. Most of the fragments of her poetry we have because someone found them in an ancient dump site. That’s just like me, I thought. I was lost, fragmented and lucky.

It is the ultimate relief – the thought that for thousands of years we have felt love and anger and desperation. One of the fragments (thirty-eight) just reads You burn me. It is tiny little messages from the past and the future coming to tell you that you aren’t alone, that we all look at the same stars and wonder what the fuck is going on. The sort of words that make you forget time and remember eternity.

I also kept up my regular visits to the library, usually with my dad who would order things weekly. That’s the thing about writers, we are a group of lonely, isolated freaks and often that’s what loads of books are about. So it is impossible not to feel a part of some great cult when you read. It is transformative.

Time swung around as it always does. I sat my A-levels. As I left the room I felt none the wiser. I could have smashed them or I could have fucked it all up. We knew that I couldn’t spend the whole summer just waiting for the results, so I went off to Rome to au pair some Italian children that a relative knew.

Tension is a powerful thing. The pulling of multiple possibilities creates an odd nervous energy. The only thing I knew for certain was that something was around the corner. It felt like there were only two possible outcomes: either I would jump and fly or I would step out and plummet off the precipice. But that is being a teenager for you, very little nuance. What I was thankful for was that something was about to happen and my life was about to change beyond what I could imagine.

I have always bragged about my ability to sleep anywhere and any time. As long as I have something resembling two out of three of dark, warmth or quiet, I can drop off. But I think that actually I massively overcompensate for the fact that for long stretches at a time I am struck by terror. I can nap during the day because at night I am possessed by psychedelic dreams and an anxious stranglehold. This started when I was waiting for my final A-level results. Every time I slept, I dreamt about picking up my grades. In these dreams, half the time I failed miserably and the other half I succeeded. I believe it was my brain putting me through a rehearsal process to ensure that I could survive either outcome.

It worked. There was no way that I was recreating the previous year’s humiliation. Bleary-eyed and petrified, I shakily rang and re-rang UCAS. When I got through, the woman on the end told me that she couldn’t give me the grades. She could only tell me if my university offers had been confirmed, but that’s all I cared about.

I cried, obviously. I’m not sure that I can express any emotion through anything but tears. I was crying so much that my dad, coming out of the shower, heard me and ran upstairs with a hand towel round his waist. I had always thought that the bit in Billy Elliot where he gets into ballet school is a bit hammy. Why doesn’t he just spit it out? But nobody could understand what I was saying because I was crying. I did it, I did it, I made it, I got in.

I went to collect my results from the school and saw how close I had been to the abyss. I got my required three As but only just, I had scraped by. I did it by one UMS mark – which is less than one mark in the actual exam. I felt the fragility of it all. Mrs Wilson wasn’t there so I didn’t have anyone to celebrate with. The headmistress just coldly said You must be pleased. They couldn’t be happy for me because they had been wrong. The next day I turned eighteen. Then I packed.

Now, I know you have probably read the blurb. You know what is going to happen. In the next chapter I am about to discover something that at this moment is unimaginable and will unravel the fabric of who I think I am. I’m sorry to break the narrative wall briefly but I believe it is very important to be explicit.

This is not a story of an inspirational disabled person overcoming adversity through hard work. I am not prepared to take on that role or represent that. I was incredibly lucky to get into Oxford; I could so easily have not got those marks. When I reflect on this part in my particular story, all I can really think about are the people who weren’t as lucky as I was. I want to be clear on my position that our current education system lets down too many people. It fails to help so many children with (and without) learning difficulties reach their full potential. The answer is not to demand that we work harder to smuggle ourselves through the system that does not want us. Trust me, we are already working so hard just to jump through the hoops you have falsely decided mark our intelligence. We should not be the collateral damage of a system that does not work.