The following weeks were a blur.

That first drive to Oxford was intense and significant. We swung into the edge of the city while our favourite Nina Simone album played. We were all singing at the top of our voices. I knew that it didn’t really matter what Oxford was like because it had been about getting there. It was symbolic for us all, that we could sneak into the system. It meant that things could change.

It was October, but the sort of autumn where the summer leaves behind a little heat. I was the new kid again but this time everyone was in the same boat as me, at least that’s what I thought. I was shown to my room by a bright sun-dressed girl in the year above who was already settled into this new world. It was welcoming.

Now, I was already quite prepared for the culture shock. I had read Brideshead Revisited years prior and I knew that I was entering into a world with new words and rules. The traditions were sewn into the fabric of the university. They were institutionalised to let everyone know that this was a hallowed, sacred place of learning – not like those other universities. At first, I bought into it.

Before I get going, I should explain some of those key things. As I have already mentioned Oxford and Cambridge are universities but they are split into smaller institutions within that called colleges. Colleges are like little villages of 400 or so students split across many years and even into masters and doctorate students. Each college has a dining hall, common rooms and their own accommodation. Generally, your main contact time is with your college tutors on top of bigger university-wide faculty teaching like lectures and classes. The college system can be great – it splits the world into manageable bite-sized chunks. In theory, it should mean that you get more attention from your teaching staff and that you can have a tiny community. But it can also be insular and at its worst it has real small-village vibes.

Where I ended up was pretty special. St Hilda’s isn’t the sort of college you think of when you imagine Oxbridge. Not even one Morse spin-off has been filmed there. As it used to be a women-only college, it is relatively new. By new, I mean created in the twentieth century rather than being a medieval shrine to the Virgin Mary, or whatever the other colleges are. There were no quads (pointless squares of grass you can’t walk on) or cloisters (those stone outdoor corridors you see in Harry Potter) or towers (big stone phalluses you can climb up). So in some ways one could be disappointed by not getting the postcard image of the oldest university in the country. But to be honest, I was just glad to be there, and as time went on I realised that not being in one of the older, more stuffy institutions was key to my happiness over the four years of my degree.

I liked that the dining room was a glorified canteen painted pink and that the food was so much better than at other colleges. The bar was student-run, and on Thursdays ran a wildly successful Pound a Pint night! The other students didn’t seem to take themselves too seriously and our sports teams were nothing to brag about. The library was nice and there was a college cat, Teabag.

My room was everything I could have ever dreamt of. I learnt later that for some reason most of the other students hated the brutalist accommodation block I had been allocated. We were put in our rooms alphabetically, like a set of library books. It was the only listed building the college had and I could see why. My room looked onto the big beech tree which stood tall over the college like a guard. Concrete and wood make this trellised building really pop in contrast to the golden sandstone of the other buildings. The corridors inside the building looked like what I imaged 1970s cruise ships sported as their chic interiors. This image was only confirmed as the year went by and I stumbled home to the swaying passage after a fiver’s worth of larger.

My dad was impressed by the Bridget Riley prints on the stairwell and by the fact I had a lift. I loved the self-contained room with its floor-to-ceiling window, single bed, sink and desk. It was a little paradise of my own, especially after my mum helped me put up the collection of postcards and vintage cigarette cards that she gave me for my eighteenth birthday.

After they left, I sat on my bed with the gingham duvet cover that I had originally slept under as a small child, and watched the autumnal sunset bathed in pride. It felt much more momentous than the rest of freshers’ week. That consisted largely of repeated conversations with people who I had no particular desire to talk to. I found it very difficult to drop the necessary guard that I had built to protect myself at school. Also, I genuinely had very little will to be liked by most of the people I encountered. I couldn’t swallow down the feeling that I wasn’t particularly a fit here either. Not because I didn’t deserve to be there, but because I just hadn’t clicked with anyone yet. It also probably didn’t help that I’d never had hummus, pesto or Prosecco before.

This was merely compounded by the constant enquiry of where did you go to school? At first I thought it was just an inane conversation starter. But as the week progressed and I heard other people’s responses, I twigged that there were famous schools other than just Eton. It made me sick that so many people had friends and acquaintances here. Some schools had sent half the year to Oxbridge. It was like this had been a viable option to them rather than some labour of impossibility come true. It really undermined the illusion of meritocracy and it made me furious.

Oxford was nothing like Batley; I had hoped for that. But there were unexpected things that made me very uncomfortable. It was so white. I was used to my classes and shops and buses having women wearing niqabs and the streets busy for Friday night prayers. Then I discovered my room had been allocated a weekly cleaner who would hoover and empty my bins. These scouts are an Oxford institution, but I couldn’t stand it (and I hate hoovering and emptying my bins). I didn’t understand why. It was not even remotely normal to me.

I have never been one for having a chip on my shoulder. Mainly, as I am aware of how lucky I am. I have the ultimate privilege of the unwavering support of my parents and that I mostly like who I am. But that first year at Oxford made me wrathful and I revelled in crossing lines. I made inappropriate jokes and swore like a sailor. I was challenging the lovely girls from the home counties and the rugby boys to try to like me. I openly laughed when I was introduced to a Benedict (Bens in my world were Benjamins) and horrified when I met two more. There is one thing I do (partially) regret; my neighbour kept walking into my room unannounced and wanting to have cups of tea and chats. After the third occasion, I said Just because our surnames start with the same letter doesn’t mean that we’re going to be friends. That was cruel. I knew it was at the time, but sometimes I can be a dick and I wanted to be left alone.

The anger came from feeling as isolated as in Batley. The only solution to that kind of solitude is to find people that make you feel less alone in the world, even if it is just momentary. Oxford, however, did introduce me to many kindred spirits. Luckily for me, I didn’t have to rely on our alphabetised living arrangements for my friends.

It is hard to say whether it was my own latent homosexuality that drew me to the androgynous figure. But like attracts like. I saw someone that was the spit of the cover of my favourite Enid Blyton book, The Naughtiest Girl in the School. It had been my favourite because it was my mum’s favourite she had actually lived up to that accolade in her own girls’ school. But here, in the auditorium of St Hilda’s college, was that girl with the mop of dark curls, but her school uniform consisted of all-black Nike Airs and about three gold chains. I knew instantly that I had seen my best friend, and Rachel Watkeys Dowie didn’t really have much to say about the situation.

The wild thing is that I was right. She was raised by artists. When I asked my parents what class we were, my mum had said we were No Class. Which is sort of right and sort of wrong. We are Bohemians; culturally rich and very cash poor. I hadn’t ever met someone else like that before, and during the first few days of Oxford it felt like maybe I wasn’t going to here, either. But as I got to know Rachel it was impossible not to see the similarities. We had got to Oxford, defying the expectations of our teachers. We had younger brothers who we loved to excess, and our parents had tried to raise us to question society’s norms of how we are supposed to be.

But unlike me, Rachel is beloved by all. She flourished in this world and used her boisterous South London charm to woo the various groups that had already started to form in the first few weeks of term. Rachel was popular and flitted in and out. Of course, I was jealous. Rach jokes that in the photos of this first year, I am always scowling and she is always smoking. She used her difference to seduce, whereas I think I used mine to push back. But I had decided she was my friend and we’ve basically stuck together in some way or another since.

That first year, Rach spent a lot of time flirting with various groups and I made one other very close friend. Olivia was from Stoke, which sounded as shit as Batley and she seemed just as angry as I was. We were thick as thieves. She studied Japanology, which I think I instantly regretted not studying the moment I realised it was an option. Cas and I had spent much of our teenage years saving up for manga volumes and Naruto-running round the house. Olivia and I instantly bonded when she dressed up as Sailor Moon in freshers’ week. She felt like the first proper friend I had ever had. She liked that I was belligerent and silly and ridiculous.

The work started straight away. There was no grace period; we were set essays in the first few days of arrival. This started the pattern for the following four years: an endless sequence of reading, essay writing and then tutes. Tutorials (or tutes if you’re nasty) are hour-long meetings with your tutors where you discuss the week’s topic such as: free will in the Iliad, column development in temples, erect penises as comic devices in political comedy, and other upstanding topics like that. Often you will have one or two other students in the room with you, but you could also frequently find yourself alone with the world’s specialist on Athenian comedy in the fifth century BC, for example. Many people are intimidated by this very thought. But I relished it. The best decision I made before I arrived at university was to resolve to have fun. I had no intention of being the cleverest because I knew that would be an impossible task. So when I went into tutorials, I asked difficult questions and thought on the spot. I had a lot of fun and got a lot wrong.

On the other hand, writing essays was a different thing altogether. I would read hundreds of pages and then try to construct some argument. But as I wrote, new ideas would sidetrack me. I would lose interest in certain threads and I would shoehorn in the information I had found on the reading list. I would deliver my essay and for those tutes where I was required to, I would read it out loud and edit it as I spoke. The words on the page seemingly unrecognisable from what I had thought I had written.

I was lucky, my tutors were not too bothered about grades. For the many essays they asked of me, they didn’t put a mark at the top. This built the atmosphere that the most important thing was the ideas and the discussion.

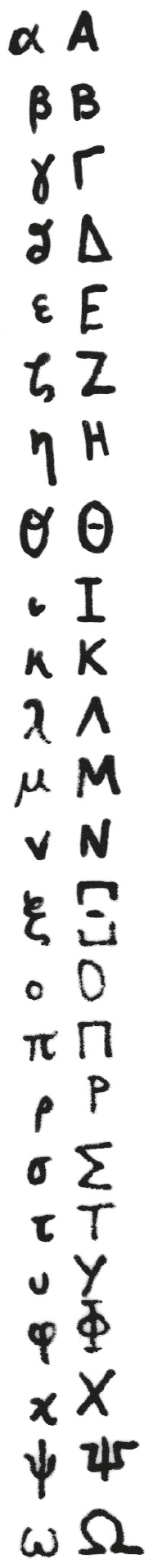

Unlike most university students in the country, I still had early morning classes. Every morning at nine I would have to drag myself to my Ancient Greek lesson. It was headed by a formidable Italian woman who was deeply unimpressed by her new cohort. How did you get into Oxford, you’re stupid! I liked her a lot; the harshness felt just like a cheeky challenge. By the end of the term she baked us a cake each week and still called us stupid. I found learning the language tricky. I did all the work set me and nothing more because it was already a mountain… I had learnt the Greek alphabet in advance, but the speed at which we moved through the tenses and grammar was impressive. Well, I’m impressed at those who managed to keep up. I did the homework and met deadlines but, if I’m quite honest, I would still trip over the new alphabet. The equivalent of r looks like a p, and I struggled to fit in all the new vocabulary. I probably needed twice the amount of time to catch up but with essays and socialising and annoying sleep dependency there was never enough time.

I thought I would meet at least a couple of geniuses in Oxford. I really had bought the propaganda. But let me assure you, there isn’t really such a thing as a genius. Even if there is, it is a dangerous role to put on someone or to take on yourself because the invisible label in front of genius is ‘doomed’. I am happily willing to take on the label of ‘lucky’ idiot. I did meet some very academic people, some who found the languages easy or were apparently sublime mathematicians but also lots of them couldn’t cook or tie their laces. Trust me when I say there are many different types of intelligence and education. Nobody has them all. Maybe you’re a social charmer who can read any room with no formal education or perhaps you’re a physics professor who has to wear Velcro shoes and can’t read an analogue clock – there really shouldn’t be a hierarchy of these skills. One is not cleverer than the other.

That first year was a real cocktail. Not like a delicious pina colada but more like how a dirty pint is technically a cocktail. Every individual part was in itself important and tasty but combined it was just a mess. I wasn’t unhappy; in fact I was over the moon just to be in Oxford. I was thirsty for the real world, which is ironic because Oxford is not the real world. But I had a culture shock. I couldn’t quite square my term time with the time I had to spend at home in the holidays. I was exhausted from the work and the parties. Then I would go back to Batley and remember that most people didn’t live the way I did at university, with three meals a day cooked for you. I pushed a lot of the discomfort aside and tried to focus on my excitement for this new world that made me feel like I was full of potential.

My accent disappeared too. I didn’t do it on purpose. I was doing a lot of auditioning for plays in Oxford and feeling like I wasn’t welcome or that the roles that were on offer were either for pretty posh girls or girls willing to play posh old ladies. The one exception was when I auditioned for John Godber’s Teechers. He’s from Hull and his plays tend to require regional accents. I shared my audition with a girl who was very keen to tell me she had done a year at LAMDA. She warmed up loudly and I shivered in my coat with cold and nerves as the draught lapped up the stone corridor. In the room, the director asked if we could do the accent. I can do just a general rough working-class voice, LAMDA girl bragged. I was so angry and so relieved in one. I got the part and she didn’t. However, she went on to get all the pretty posh-girl roles for the following three years. That was just one of the messages Oxford sent me about my voice.

The second message I received even louder and clearer. I was asked to go to an alumni event. It was hosted in the Houses of Parliament and there was free booze. I dressed up in a black velvet dress from a vintage shop; in the light you could see green roses shine in the fabric. I really looked the part as I swanned into the room filled with ex-students. There were lots of old white ladies. Most were very formidable and successful. I fell into conversation with one who was in her seventies and who had studied classics half a century ago. I was explaining to her the new course I was on where you could learn Latin and Greek from scratch. She kept tutting at me. I changed the topic. I tried to inspire her with talk of Euripides. She interrupted me. Really, I can’t listen to you speak a word more. Stop saying ‘like’. You sound dreadful. Nobody will ever take you seriously with a voice like that. Stop crying. I’m helping you. Young women like you sound like idiots. I swiftly ran to the toilets.

Now people ask, So where’s your accent? You don’t sound northern. You can be sure as shit they have the same innocuous nothing voice. I dismiss it, joking that a posh university bashed it out of me. It is easier to credit the loss of my accent to just that one thing and not a long accumulation of experiences outside the county where what I said and how I said it was repeated back to me over and over again. It’s easier than to say I felt unwelcome or that I felt like I had to squash it out so that I could fit in. How else could I see myself in that space with my voice? Now it feels like a price I had to pay to leave Batley.

It’s still there, just a little bit if you listen. My A’s are flat and to’s are t’s. Ah’ll see ya ten-tuh-two. When I’m angry or a pint down, it tumbles out as strong as ever. It makes me happy to hear that it didn’t get completely trampled out. I think about how on earth do I get it back – do I consciously put it back on? But it’s not a hat I can just don. That would make it feel like a costume, when it’s so much more complicated than that. In many ways I got what I wanted. I wanted to leave, I didn’t want my future tied to that one place forever. But I certainly didn’t want to erase my past and my roots and my voice in the process.

I was grappling with all of that in the first year. But I went into the second year feeling a bit more confident. I had some big exams coming up and I had a student house so I could stay in Oxford outside term time. It felt like maybe I could solidify my place in this new world rather than flip-flopping between the two places.

My mum drove me to my new house on her own because Dad was away. I was the first one to move in. I was anxious about it as I had to arrange my housemates early the previous year; Rachel was one of them but I wasn’t close to the other three girls. Olivia was in Japan on her year abroad but I was planning to go out and visit her in one of the holidays. I was worried about being even more lonely without my friend. After we had set up my room, Mum disappeared off leaving me in this strange house alone.

I started making myself some haute cuisine – probably some sort of pasta or egg-based dish on the electric hob. The new kitchen was weird. It had fake wood panelling, which gave it a 1970s ski chalet vibe. I was engrossed in thinking about this new environment when I tripped up and fell forward, steadying myself with my right hand. I didn’t see as I flew head first that my hand was heading towards the hob. As I pulled my hand away I could smell the burning skin. I called my mum, now halfway up the M1, with my hand under the cold tap. We didn’t have the Internet installed yet so I had Cas read the NHS advice page down the phone to me: if the burn is larger than the palm of your hand, go to your local A&E department. Well, at least I had an accurate measure of the blister size. That night I lay in my new bed with my hand in a bowl of water and cried. I’m afraid to say that it really set the tone for that second year.

The house filled up with my housemates and I continued to feel alone. A classmate ripped me apart for being excited about buying a new mobile phone. You’re so privileged you don’t understand. It was my second ever phone and later I went to her house and met her mother the high court judge and realised that the guilt was maybe misplaced. I didn’t hear from Olivia for months. Rachel got her first girlfriend, which meant I didn’t see her much. My bike kept breaking and my exams were fast approaching. One of my housemates wouldn’t let me put on the heating and my windows weren’t sealed properly so the room was well ventilated. I ended up sleeping in the fur coat I had bought to look the part at balls, which felt more Withnail and I than I had anticipated.

Eventually, I got an email from Olivia. She evidently was also not in a good place. But she said she no longer wanted to be my friend, that I was negative and saw the worst in people and that it was poisonous. It was like she had used all the things I had told her in confidence that I hated about myself to destroy me. Together, we had always said that maybe the rest of the world needed to be better but here she was telling me that I was the problem. This was completely unforeseen. She had played a key part in my navigation of Oxford. She had felt as much of an outsider as me and I had been deeply touched by her presence in my life.

It is impossible not to take such a comment to heart when it comes from someone you love. I was flooded and drowning. All the things that I had hidden away in deep crevices of my being paraded up into focus. Like a monkey with a cymbal bashing my brain cried out lethal! polluting! vicious! toxic! noxious! corruptive! viperous! I didn’t know I knew so many synonyms and that I was capable of weaponising my vocabulary against myself so brutally.

I tried my best to just hold it all far away from me for as long as possible. If it gets me, I thought, I am going to die. I wasn’t going to kill myself but I was pretty certain I was going to get hit by a bus while cycling, maybe. It was that terrifying feeling of impending doom and, even more scarily, the idea that I might do something to speed up the inevitable. I cried on Rachel a lot. The sky was low and had the quality of office ceiling tiles. I called my parents and asked them to come get me, weeks before I had planned. She broke your heart, said Mum and I let myself be eaten by the sadness. It didn’t kill me. The thought of how much it was going to hurt was worse than just feeling the loss.

The next term heralded my first big exams at Oxford. They’re called Mods and they’re famously (apparently – I didn’t know before, either) gruelling. Hardest exams in the world tied with the Chinese civil service ones until they made those easier last year, I once heard someone claim. I googled the Chinese civil service exams only to find out that they were in place from the Zhou dynasty (1067-ish) to the end of imperialism in China (1911) so I assumed that someone was talking out of their arse, not an uncommon thing in the dreaming spires. I wasn’t too worried because I had sort of kept up with my work, I never handed in stuff late and I wrote the essays. I just needed to revise. So as I tried to recover from what I thought might have been depression and now recognise as grief, I spent hours in the library. I would try to read and make notes and not cry too openly. Funnily enough, it felt like most people in the library, with or without exams, seemed to be doing the same thing.

The exams came round and we had to sit eleven three-hour exams in eight days. In Oxford, another one of the weird traditions is that you have to sit exams in a uniform called subfusc, which is essentially a black-and-white costume – white shirt, black tie or ribbon and black skirt or trousers; oh, and a gown. You sit the exams in the building where humanities lectures are held, called Examination Schools. The 400 people doing your subject are herded up marble staircases into these beautiful high-ceilinged rooms. Then, at the end of the exams you get trashed, which sounds like the binge drinking you would expect at every university but trashing is when your friends cover you in shaving foam and confetti and booze.

Before the exams, I had thought these were great symbols – like arming yourself before war and the catharsis of mess. But half an hour into my first paper on the Iliad, I was uncomfortable and the echoey room was draughty and noisy. When I finished all my exams I exited only to find that nobody had come to trash me. Bloody traditions, I muttered to myself as I skulked off to the pub with my fellow classicists, my drab clothes still pristine. I watched in amazement as one of the boys from St Hilda’s downed a pint of Guinness, and realised that we all probably hadn’t had the most fun in Exam Schools. I wondered who exactly benefitted from all the rigmarole.

I had ticked off each exam. They were hard, obviously, and I was still manically writing to the last minute and not having time to check through, let alone really even think. In one I was required to translate a passage from English into Ancient Greek, which is a ridiculous thing to ask someone to do. Translating the other way round is, yes, a specialist skill but at least has a point. The only possible reason to do it the other way round might be if you found yourself in a time-travel rom-com scenario (possible titles – Bacchus to the Future, You were never really Hera, There’s no place like Homer).

I had revised for this exam but found myself struggling to recall anything I had learnt over the last year and a half. The only foreign language I could think of was French (which I had studied for A-level but I wouldn’t say I was fluent by any stretch of the imagination). I thought I was writing in Ancient Greek but when I got my results back I realised I couldn’t have been. I failed that exam so badly that I must have been writing in French but in the Greek alphabet. µερδε.

Now, failing my second set of exams still sucked. But this time, it was mainly just the shame. I didn’t need the grades for anything in particular but I was used to the idea of doing well. I emailed my tutors who assured me that I didn’t have to retake the failed papers because I’d managed to wangle a 2:2 overall. I know you must be disappointed but they don’t count so please don’t worry about it, Dr Kearns replied. Now I see how lucky I was, lots of other tutors would be annoyed and think about their college rankings, but not mine.

I had just picked my papers for the second half of my degree, opting perhaps foolishly to learn Latin from scratch after the overwhelming success of my Greek papers. But I wanted to be able to translate both classical languages and I had my heart set on the Ovid paper for some reason. I don’t like giving up, unless it’s sports related and in that case I don’t even really get started. We just carried on with tutorials and essays and reading and language classes. I was so used to the seemingly random highs and lows of my academic life. This was normal for me. I concluded that I must just be erratic.

At the end of summer term (they call it Trinity, and not because they love The Matrix but because of tradition) things were looking up. It was sunny, I was about to move into a rad flat with cool people and I was flirting with a girl who would soon become my first girlfriend. I went to go have my termly report reading and Dr Kearns had written I suspect there might be some undiagnosed dyslexia here. I sat on the low sofa where I had been interviewed two and a half years previously, and I began to cry and panic. My tutor looked alarmed but I can assure you she wasn’t as alarmed as I was.