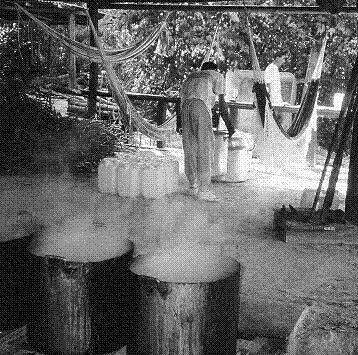

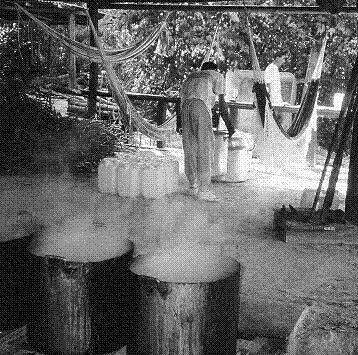

Chapter 46 - Climbing the Vine: 1991

Preparing

hoasca

at the UDV temple in Manaus, Brazil.

My seemingly perpetual status as a postdoc came to an end sometime in the spring of 1990. Peroutka was about to leave Stanford for a plum position as the director of neuroscience at Genentech, the first of several positions he’d go on to hold in the world of corporate biomedicine. He told me that I should start making plans to find a real job, if such was to be had. I had been applying for various academic positions, but none of the recruiting committees seemed to know quite how to respond to my peculiar academic pedigree as a botanist/neuroscientist with a passionate interest in psychedelics. I was ready to move on from Stanford, because I wanted to find a way to merge my newly acquired skills in neuroscience and central nervous system (CNS) pharmacology with my longstanding interests in ethnobotany and natural products. But the way forward wasn’t clear, and I was worried about finding the next gig.

Then, a lucky break: I was contacted by Mark Plotkin, a Yale ethnobotanist and protégé of Schultes who would soon achieve national fame for his 1993 book Tales of a Shaman’s Apprentice: an Ethnobotanist Searches for New Medicines in the Amazon Rainforest

. We had met briefly when I attended a presentation he made at NIH. There was a new startup company being formed in the Bay Area called Shaman Pharmaceuticals, he said, and its mission was focused on ethnobotanically driven drug discovery, especially drugs from the Amazon Basin. They already had one antiviral candidate in the pipeline, and were planning to create a CNS drug discovery program. They needed young, smart, ambitious people like me.

Shaman Pharmaceuticals was the visionary brainchild of Lisa Conte, an ambitious young entrepreneur who had been a vice-president at a venture capital firm with offices in the area. She had managed to garner about $4 million in venture capital funding as well as personal funds and had founded Shaman after observing local healers using plant medicines during travels in Asia. Schultes, and later the famous pharmacognosist Norman Farnsworth, were persuaded to join their advisory board. At the time, Conte needed people to join the core team, Mark told me, and they were hiring. I should go talk to her, which I did.

For me, it was like a dream come true. Ever since San Diego, I had made efforts to found a company that would do exactly what Shaman Pharma intended to do. I had good ideas for drug discovery but no business experience or expertise whatever. Now here was a new company run by those with the business skills to realize what I had only dreamed of doing. Moreover, I had something to offer, in the form of the skills I had developed during my postdocs at NIMH and Stanford. Although their primary therapeutic target was antivirals, they also were interested in novel analgesics and needed people to work in both areas.

My stint at Shaman would be my introduction to corporate science. I stayed with the company until the end of 1992 and enjoyed my work there. The other scientists, with some exceptions, were a good bunch to work with, and we believed in our mission. I felt like I had a contribution to make.

For most of my tenure at Shaman I was a lab rat, working in the receptor lab on the lower floor of their facility in San Carlos. Other Shamanites got to travel the world in search of exotic plants, a role I might have envied had I not been so happy to stay at home with my wife and young daughter.

In 1991, I did escape temporarily, thanks to an invitation I got to describe my work on ayahuasca at a conference in São Paulo, Brazil. The conference had been organized by the medical studies section of the União do Vegetal, or UDV, one of the syncretic churches in Brazil that uses ayahuasca as a sacrament. (Ayahuasca, in Portuguese, is called hoasca

, and UDV followers often refer to it as vegetal

). The conference was a multidisciplinary event that included chemists, neuroscientists, pharmacologists, anthropologists, and psychiatrists. My friend Luis Eduardo was there along with other knowledgeable figures.

For the UDV, it was an important event, given its political subtext. At the time, CONFEN, the Brazilian drug agency, was debating whether ayahuasca was a dangerous substance liable to abuse, and whether its use in religious practices should be banned. The UDV wanted to show that hoasca

was inherently safe, not subject to abuse, and that its ritual use should be allowed. By inviting a distinguished roster of international experts, they hoped to present an impressive conference that would favorably influence the CONFEN authorities. It seemed strange to me that I was regarded as one such “distinguished” expert on ayahuasca, but I suppose I was.

During our travels in Peru in 1985, Eduardo and I had both mused about the possibility of conducting a biomedical study of ayahuasca. Many of the ayahuasqueros

we dealt with seemed remarkably healthy in mind and body, and many, though quite elderly, were still quite strong. We asked a naive question: was there something about long-term, regular ingestion of ayahuasca that enhanced their health and vigor? We speculated about ways that we might approach that question, and I even started drafting a grant application to NIDA after we returned home. I quickly realized that, in Peru, we’d have trouble conducting a study that involved asking for blood and urine samples; that wouldn’t be appropriate in light of cultural attitudes about witchcraft. And even if we got the samples, they’d be difficult to preserve. Beyond the logistical problems loomed the simple fact that NIDA would never fund such a study. So we shelved the idea at the time.

But it turned out that the organizers of the UDV conference had exactly that kind of a project in mind. That was their real agenda; they wanted to enlist the help of recognized foreign scientists to carry out a biomedical study among UDV members that, they hoped, would support their petition to CONFEN to allow the sacramental use of the hoasca

tea. In this case, the logistics were more realistic. Many of the UDV members were themselves physicians, there was no cultural baggage involving witchcraft to contend with, and there were many UDV members who were eager to submit themselves to poking and prodding. So with the encouragement from top UDV mestres

, I returned to the States and dusted off my old proposal. I revised and submitted it to them for their approval, which they gave. I started soliciting funds through Botanical Dimensions, and over the course of the next couple of years we were able to raise about $75,000 to conduct the study.

But that lay ahead. Back at the conference, after three days of PowerPoints and roundtables at a UDV temple on the outskirts of São Paulo, the event culminated in an ayahuasca ceremony with the foreign dignitaries as the guests of honor. About 500 people took part in that ceremony. I had a profound visionary revelation, in which I experienced photosynthesis from a molecule’s eye view, and understood the importance of this everyday miracle for the sustenance of life on the planet. It was a cathartic and moving experience, one of my most profound ayahuasca journeys. The following account of my “lesson from the Teacher” has been adapted from an earlier version that appeared in Ayahuasca Reader: Encounters with the Sacred Vine

(Luna and White, 2000).

On the night in question, the weather was humid and balmy. In the gathering dusk, we all walked the short distance from the dormitories where we had been staying to the temple, nestled in a small valley about a quarter mile away. In the center of the amphitheatre-like space, a long table was arranged, with chairs arrayed around it and a picture of Mestre Gabriel, the UDV founder and prophet, hung beneath an arch-shaped structure decorated with the sun, moon, and stars at one end. Several gallons of hoasca

tea, a brownish liquid the color of café latte, was in a plastic juice dispenser placed on the table beneath the picture of Mestre Gabriel; beside it was a stack of paper picnic cups.

A special set of chairs had been reserved for the visiting dignitaries along one of the terrace-like elevations close to the center of the amphitheater. We threaded our way among the members already seated and took our places in the reserved spot.

After everyone had gotten settled, the mestre

in charge rose to start dispensing the brew, helped by a couple of acolytes. The members formed an orderly line, and one by one we filed down to stand before the mestre

and be handed a paper cup containing our allotted draft; the size of the servings varied from person to person, and seemed to be measured according to body weight and the mestre’s

assessing gaze; one got the feeling that he was taking the measure of the soul and spirit of the supplicant standing before him. Each person took their cup and returned to stand in front of their chair. Once everyone had been served, the mestre

gave a signal and all raised the cups to their lips and drained the bitter, foul-tasting beverage in two or three gulps. One of the Brazilian scientists standing beside me slipped me a small piece of dried ginger to chew to kill the aftertaste; I was grateful for the kind gesture.

Having drained their cups, everyone sat back in their comfortable webbed chairs. I kept hoping someone would turn off the glaring, buzzing, fluorescent lights overhead that were altogether too bright and quite annoying. They were to stay on during the entire evening, however. For about forty-five minutes, everyone sat, absorbed in their own thoughts. The crowded hall was absolutely silent. After this period, a few people began to get up and totter toward the bathrooms as the nausea, a frequent side effect in the early stages, began to take hold. About the same time, the mestre

began singing a beautiful song, called a shamada

, and though I could not understand the Portuguese words, the melody was quite moving. The sound of the heartfelt shamada

mingling with the wretching, gasping noises of people throwing up violently in the background made me smile at the incongruity, but no one else seemed to notice.

My own experience was not developing as I’d hoped. My stomach was queasy but not enough to send me to the bathroom, and I felt restless and uncomfortable. I felt very little effect, except for some brief flashes of hypnagogia behind my closed eyes. I was disappointed; I had been hoping for more than a sub-threshold experience. When the mestre

signaled that he was ready to give a second glass to anyone who wanted it, I was among the group of about a dozen gringos that queued up in front of the table; apparently I was not the only one who was having a difficult time connecting with the spirit of the tea.

I took my second drink and settled back into my chair. It tasted, if possible, even worse than the first one had. Within a few minutes it became clear that this time, it was going to work. I began to feel the force of the hoasca

course through my body, a feeling of energy passing from the base of my spine to the top of my head. It was like being borne upwards in a high-speed elevator. I welcomed the sensation as confirmation that the train was pulling out of the station.

The energized feeling and the sensation of rapid acceleration continued. It was much like mushrooms but seemed to be much stronger; I had the sense that this was one elevator it would be hard to exit before reaching the top floor, wherever that might be. Random snippets of topics we had been discussing at the seminars in the previous days began to float into my consciousness. I remembered one seminar that had addressed the UDV’s concept that the power of hoasca

tea is a combination of “force” and “light.” The force was supplied by the MAO-inhibiting Banisteriopsis

vine, known as mariri

in the local vernacular, while the light—the visionary, hypnagogic component—was derived from chacruna

, the DMT-containing Psychotria

admixture plant. I thought to myself what an apt characterization this was; hoasca

was definitely a combination of force and light, and at that moment I was well within the grip of the force and hoped that I was about to break out into the light.

At the instant I had that thought, I heard a voice, seeming to come from behind my left shoulder. It said something like, “You wanna see force? I’ll show you force!” The question was clearly rhetorical, and I understood that I was about to experience something whether I wanted to or not. The next instant, I found myself changed into a disembodied point of view, suspended in space, thousands of miles over the Amazon basin. I could see the curvature of the earth, the stars beyond shone steadily against an inky backdrop, and far below I could see swirls and eddies of clouds over the basin, and the nerve-like tracery of vast river systems. From the center of the basin arose the world tree, in the form of an enormous Banisteriopsis

vine. It was twisted into a helical form and its flowering tops were just below my disembodied viewpoint, its base was anchored to the earth far below, lost to vision in the depths of mist and clouds and distance that stretched beneath me.

As I gazed, awestruck, at this vision, the voice explained that the Amazon was the omphalos of the planet, and that the twisted, rope-like Yggdrasil-mariri

world tree was the lynchpin that tied the three realms—the underworld, the earth, and the sky—together. Somehow I understood—though no words were involved—that the Banisteriopsis

vine was the embodiment of the plant intelligence that embraced and covered the earth, that together the community of the plant species that existed on the earth provided the nurturing energy that made life on earth possible. I “understood” that photosynthesis—that neat trick, known only to green plants, of making complex organic compounds from sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water, was the “force” the UDV was talking about, and indeed was the force on which all life depends; I was reminded of a line from Dylan Thomas, that photosynthesis is “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower.”

In the next moment, I found myself instantly transported from my bodiless perch in space to the lightless depths beneath the surface of the earth. I had somehow become a sentient water molecule, percolating randomly through the soil, lost amid the tangle of the enormous root fibers of the Banisteriopsis

world tree. I could feel the coolness, the dank dampness of the soil surrounding me, I felt suspended in an enormous underground cistern, a single drop among billions of drops. This sensation lasted only a moment, then I felt a definite sense of movement as, squeezed by the implacable force of irresistible osmotic pressures, I was rapidly translocated into the roots of the Banisteriopsis

tree; the sense of the rising, speeding elevator returned except this time I was being lifted rapidly through the vast pipes and tubes of the plant’s vascular system. I was a single molecule of water tumbling through the myriad branches and forks of the vertical maze, which grew progressively narrower the higher I went.

Finally, the sense of accelerating vertical movement eased off; I was now floating freely, in a horizontal direction; no longer feeling pushed, I was suspended in the middle of a stream flowing through an enormous, vaulted tunnel. More than that, there was light at the end of the tunnel, a green light. With a start I realized that I had just passed through the petiole of a sun-drenched leaf, and was being shunted into progressively narrowing arteries as I was carried through the articulating veins toward some unknown destination. It helped that the voice—or my own narrative self, I’m not sure which—was providing occasional commentary on the stages of the journey as it unfolded.

Desperately I tried to remember my old lessons in plant physiology and anatomy. By this time I had been given the wordless understanding that I was about to witness, indeed, participate in, the central mystery of life on earth: a water molecule’s view of the process of photosynthesis. Suddenly, I was no longer suspended in the arterial stream of the leaf vein; I had somehow been transported into an enormous enclosed space, suffused with greenish light. Above me I could see the domed, vaulted roof of the structure I was inside of, and I understood that I was inside a chloroplast; the roof was translucent and beams of sunlight streamed through it like a bedroom window on a bright morning. In front of me were flat, layered structures looking like folded sheets stacked closely together, covered with antenna-shaped structures, all facing in the same direction and all opened eagerly to receive the incoming light. I realized that these had to be the thylakoid membranes, the organelles within the chloroplast where the so-called “light reaction” takes place. The antenna-like structures covering them literally glowed and hummed with photonic energy, and I could see that somehow, this energy was being translocated through the membranes of the thylakoids they were mounted on. I recognized, or understood, that these antenna-like arrays were molecules of chlorophyll, and the “anchors” that tied them to their membrane substrates were long tails of phytic acid that functioned as energy transducers, funneling the light energy collected by the flower-shaped receptors through the membrane and into the layers beneath it.

Next thing I knew, I was beneath that membrane; I was being carried along as though borne on a conveyor belt; I could see the phytic acid chains dangling above and beyond them, through the semitransparent “roof” of the membrane, the flower-like porphyrin groups that formed the chlorophyll’s light-gathering apparatus loomed like the dishes of a radio telescope array. In the center of the space was what looked like a mottled flat surface, periodically being smited by enormous bolts of energy that emanated, lightening-like, from the phytic acid tails suspended above it; and on that altar water molecules were being smashed to smithereens by the energy bolts. Consciousness exploded and died in a spasm of electron ecstasy as I was smited by the bolt of energy emitted by the phytic acid transducers and my poor water-molecule soul was split asunder.

As the light energy was used to ionize the water, the oxygen liberated in the process rose with a shriek to escape from the chamber of horrors, while the electrons, liberated from their matrix, were shunted into the electron-transport rollercoaster, sliding down the chain of cytochromes like a dancer being passed from partner to partner, into the waiting arms of “photosystem I,” only to be blasted again by yet another photonic charge, bounced into the close but fleeting embrace of ferredoxin, the primary electron acceptor, ultimately captured by NADP+

to be used as bait to capture two elusive protons, as a flame draws a moth. Suddenly I was outside the flattened thylakoid structures, which from my perspective looked like high-rise, circular apartment buildings. I recognized that I was suspended in the stroma, the region outside the thylakoid membranes, where the mysterious “dark reaction” takes place, the alchemical wedding that joins carbon dioxide to ribulose diphosphate, a shotgun marriage presided over by ribulose diphosphate carboxylase, the first enzyme in the so-called pentose phosphate shunt. All was quiet and for a moment, I was floating free in darkness; then miraculously—miracles were by this time mundane—I realized that my disembodied point of view had been reincarnated again, and was now embedded in the matrix of the newly reduced ribulose diphosphate/carbon dioxide complex; this unstable intermediate was rapidly falling apart into two molecules of phosphoglycerate, which were grabbed and loaded on the merry-go-round by the first enzymes of the Calvin cycle. Dimly, I struggled to remember my early botany lessons and put names to what I was seeing.

I recognized that I had entered the first phases of the pentose phosphate shunt, the biochemical pathway that builds the initial products of photosynthesis into complex sugars and sends them spinning from thence into the myriad pathways of biosynthesis that ultimately generate the molecular stuff of life.

I felt humbled, shaken, exhausted, and exalted all at the same time. Suddenly, I was ripped out of my molecular rollercoaster ride, and my disembodied eye was again suspended high over the Amazon basin. This time, there was no world tree arising from its center; it looked much like it must look from a spacecraft in orbit. The day was sunny, the vista stretching to the curved horizon was blue and green and bluish-green, the vegetation below, threaded with shining rivers, looked like green mold covering an overgrown petri plate. Suddenly I was wracked with a sense of overwhelming sadness, sadness mixed with fear for the delicate balance of life on this planet, the fragile processes that drive and sustain life, sadness for the fate of our planet and its precious cargo.

“What will happen if we destroy the Amazon,” I thought to myself, “what will become of us, what will become of life itself, if we allow this destruction to continue? We cannot let this happen. It must be stopped, at any cost.” I was weeping. I felt miserable, I felt anger and rage toward my own rapacious, destructive species, scarcely aware of its own devastating power, a species that cares little about the swath of destruction it leaves in its wake as it thoughtlessly decimates ecosystems and burns thousands of acres of rainforest. I was filled with loathing and shame.

Suddenly, again from behind my left shoulder, came a quiet voice. “You monkeys only think

you’re running things,” it said. “You don’t think we would really allow this to happen, do you?” And somehow, I knew that the “we” in that statement was the entire community of species that constitute the planetary biosphere. I knew that I had been given an inestimable gift, a piece of gnosis and wisdom straight from the heart-mind of planetary intelligence, conveyed in visions and thought by an infinitely wise, incredibly ancient, and enormously compassionate “ambassador” to the human community. A sense of relief, tempered with hope, washed over me. The vision faded, and I opened my eyes, to see my newfound friends and hosts all eagerly gathered around me. The ceremony had officially ended a few minutes earlier; I had been utterly oblivious to whatever was going on in the world beyond my closed eyelids. “How was it,” they wanted to know, “did you feel the buhachara

, the strange force?” I smiled to myself, feeling overjoyed at the prospect of sharing the experience and knowing that I had indeed been allowed to experience the ultimate “force,” the vastly alien, incredibly complex molecular machine that is “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower.”