THE POSTER BOY FOR THE JET SET HAD A BIG SECRET. FRANK SINATRA WAS AFRAID of flying. His 1958 album Come Fly with Me had become the soundtrack for the new jet age that had kicked off that same year in October with Pan Am’s 707 service between New York and Paris. Yet Sinatra wouldn’t be caught dead on Pan Am or TWA or even Air France, no matter how good the meals, catered by La Tour d’Argent, were supposed to be. “Dead” was the operative word for Sinatra, that most distrustful of all superstars. He simply didn’t believe the airlines were careful enough. That was why he had his own plane, a big dual-prop Martin 404 called, in those days before political correctness, El Dago. Before the advent of the jets, the Martin was state-of-the art, air-conditioned, pressurized, and customized for his hard-drinking Rat Pack show-business buddies, with a piano and a central bar almost as long as the one at Chasen’s. Hollywood felt at home here in the air, though for the nervous Sinatra, the El Dago bar was a necessity rather than a status symbol.

Aside from insisting on war-hero private pilots, Sinatra obsessively had his valet, ex–navy man George Jacobs, spend even more time checking weather reports and communicating with all the airports on their prospective routes to make sure there would be no nasty surprises than Jacobs did in arranging starlet assignations for his master. Sinatra once threw a fit when Jacobs arranged a post-dinner screening of the classic airline near-disaster film, The High and the Mighty, notwithstanding John Wayne’s saving the day—and the plane. And he confided in Jacobs that he had a recurring nightmare inspired by The Glenn Miller Story, wherein the big bandleader disappeared over the foggy Channel on a flight from England to Paris. Moreover, Sinatra was still haunted by having bailed out, at the last second, of a 1958 cross-country flight with Around the World in 80 Days impresario and Elizabeth Taylor husband Mike Todd on his plane The Lucky Liz, which went down in a fireball in a New Mexico cornfield.

Such high anxiety was not the stuff of American legends, especially that of the swaggering, carefree, ring-a-ding variety that Sinatra apotheosized. He knew he had to get with the program, the jet program. After all, he was supposed to be the program. Accordingly, in 1962, when the ocean liners were still carrying more passengers across the Atlantic than the new jets, Sinatra did more than anyone thus far to emblazon the jet fantasy in the still-sedentary imagination of America. His high-profile grand gesture was chartering his own 707 for a three-month round-the-world tour to benefit children’s charities in the countries he would visit. He would fly from L.A. to Tokyo, to Hong Kong, then across the globe to Israel, Greece, Italy, France, England, a swinging, speedy update of the grand tour for the Sputnik era.

What the world didn’t realize was that, for all his ostensible altruism, Sinatra’s charity began at home. The new commercial jets may have needed passengers, but Sinatra needed something, too: a makeover of a Mafia image occasioned by his guilt-by-association relationship with Chicago Mob boss Sam Giancana. While Giancana may have been instrumental in stealing Illinois, and the presidency, for John F. Kennedy in 1960, it was a debt that Attorney General Bobby Kennedy was intent on wiping from the ledger, even if that meant obliterating the playboy friendship between Sinatra and his brother. Bobby was so down on Sinatra, who had reconstructed his Palm Springs compound to become JFK’s own Western White House, that he pressured his brother into rejecting the Sinatra hospitality and bunking instead chez Bing Crosby, Sinatra’s archrival and an even archer Republican.

Humiliated, Sinatra, at the advice of his master-strategist lawyer, Mickey Rudin, decided to get out of Dodge—all the way out to Tokyo, as far as a 707 would take him. His entourage wasn’t comprised of the usual Jet Set suspects, ultramobile international legends like Onassis, Agnelli, Rubirosa, or even Jacqueline Kennedy herself, whose high-profile Francophilia was proving to be a greater gesture of Franco-American comity than the Statue of Liberty. No, instead of the global nomads, Sinatra filled his 707 with his regiment of musicians and his best local buddies. The latter included his favorite Beverly Hills restaurateur, “Prince” Mike Romanoff, everyone’s favorite charlatan, on whom Sinatra counted to get him the best tables on earth; his personal banker, Al Hart, head of Beverly Hills’s City National and the man who financed Sinatra’s comeback film, From Here to Eternity, to pay the freight; his songwriter and sexmeister Jimmy Van Heusen, himself an accomplished pilot, to get the girls; and legendary New York Giants baseball manager Leo “The Lip” Durocher, to provide all-American ballpark ballast amid the anticipated dislocations and alienations of the long foreign journey.

While not exactly the Ugly American, Sinatra provided plenty of his own homegrown ballast. For all his previous international performances and global exposure, Sinatra had almost no interest in foreign cultures, except for the women. He couldn’t have cared less about the Louvre or Versailles, classic architecture or haute cuisine. In fact, he had George Jacobs stock the 707 with a three-month supply of his favorite snack, Campbell’s franks and beans, which he would devour cold, straight from the tin. This was soul food, Hoboken-style. God forbid Sinatra would have to ingest sushi or chop suey or foie gras or, even on his ostensible home turf, spaghetti alla vongole. Even in Italy, the star invariably rejected the alta cucina grand-hotel fare of Rome’s Excelsior and Milan’s Principe di Savoia. Instead, he insisted that Jacobs, an accomplished navy cook whom Sinatra’s mother Dolly had taught to “do” bridge-and-tunnel red-gravy transplant-paisan food, prepare his Jersey favorites in the kitchen of his suite.

Sinatra left for Tokyo in April 1962, perfect for cherry-blossom time. His tour instantly generated massive worldwide news coverage, just as lawyer Rudin had promised. Every day the still-powerful syndicated gossip columns, led by Hearst’s “Cholly Knickerbocker,” the nom de plume of the worldly and genuine Russian count Igor Cassini, featured breathlessly glamorous dispatches on Sinatra’s mix of good deeds and high life, visiting a Buddhist monastery on Mount Fuji, endowing a youth center on the Sea of Galilee, cruising the Mediterranean on Onassian yachts, serenading his High Society costar Princess Grace at a series of “Chinchilla and Diamonds” concert benefits at the Sporting Club in Monte Carlo designed to soak high rollers for the benefit of poor kids.

Sinatra had El Dago flown over to Europe to replace the 707 for short intercontinental hops, though in a nod to his quest to sanitize his escutcheon, it had been renamed the Christina, after his younger daughter. He posed with blind children in Greece and crippled children in Italy and orphans in England. He sang everywhere, from the Mikado Theater in Tokyo, to the Parthenon in Athens, to the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, to the Royal Festival Hall in London. He was feted by everyone from the emperor of Japan to Princess Grace to Princess Margaret (whom he tried, unsuccessfully, to bed) to General de Gaulle, who got over being not invited by Prince Rainier to the Monaco gala and decorated Sinatra as a chevalier of the Order of Public Health, an ironic honor given the unsalubrious post-concert orgies being carried on in the entertainer’s imperial suite at the Hotel George V. The fantasy trip of a lifetime, Sinatra’s “one man, one world” extravaganza underscored, as nothing before it, the jet-age miracle of making the planet seem, if not small, then certainly accessible.

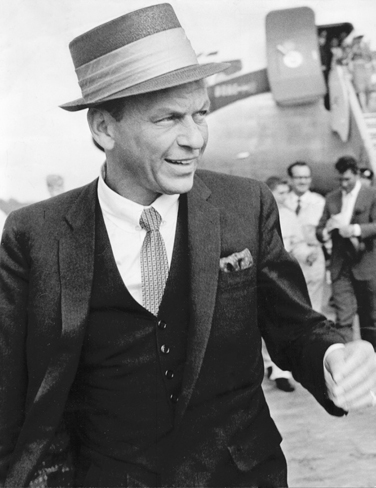

COME FLY WITH ME. Frank Sinatra at London’s Heathrow Airport in 1961. More than any other entertainer, Sinatra embodied and popularized jet travel. (photo credit 1.1)

The Sinatra coverage was proving an inspiration to another group of travelers who were planning their own trip-of-a-lifetime spring adventure to Europe, an odyssey that would be as long on culture as Sinatra’s would be short. The Atlanta Art Association, which constituted the art- and music-loving elite of the capital of the Peach State and the symbol of a South that was rising again, was chartering an Air France 707 to take its members on a very grand tour of the Old World for the month of May. Just as the Sinatra world tour would become the most-reported-on celebrity superjunket of the sixties, the Atlanta art excursion would become the most-reported-on tour of “real people,” although for entirely different reasons, as will be seen.

Sinatra was fantasy, Atlanta reality. Both captured the public imagination. The Art Association trip would be featured on the cover of Life as a paradigm of how the new jets were opening up the Old World to America’s burgeoning middle class, and how travel was becoming both an affordable luxury and, for Americans in the Camelot era that prized sophistication, a cultural necessity. The Atlanta tour thus provides valuable insight into how Americans traveled at the dawn of the jet age and the joy it brought them. Sadly, the main reason it made Life was death, for the tour, realizing Sinatra’s darkest fears, became the greatest disaster in aviation history.

In 1960, following its own assemblage of a jet fleet to compete with Pan Am and TWA in the war for the Atlantic, Air France had established a sales office in Atlanta. Its local manager was a suave and dashing Frenchman named Paul Dossans, who proved enormously attractive to the local country-club set who were Air France’s target clientele. Dossans started small, donating a free jet round-trip ticket to Paris to the Art Association’s 1960 charity auction. The prize turned out to be such a hit that Dossans decided next to go for not one seat but the whole plane. He joined forces with the local American Express office to assemble a tour and charter package exclusively for the Art Association.

Exclusivity, embodied in the Piedmont Driving Club, which had a large overlapping membership with the Art Association, was everything in Atlanta. The boomtown was still suffering from the century-old inferiority complex vis-à-vis the “Yankee” metropolises occasioned by General Sherman’s having burned it to the ground. Atlanta didn’t have anything like the Metropolitan Museum or the Metropolitan Opera, but it did have a Gone with the Wind gracious mystique, it had the global colossus of Coca-Cola, and it had a huge amount of new money that wanted to burnish itself with an “artistic” patina. It was a perfect target for Air France, and in teaming up with an Art Association grand dame named Anne Merritt, Paul Dossans hit the Dixie bull’s-eye.

In return for a free first-class ticket, Dossans got Merritt, the wife of a Harvard-trained fertilizer broker, to fill up his plane with 120 of her society friends. Merritt was already a world traveler, though doing so from pre-707 Atlanta was a major pain, requiring numerous stopovers and basically twenty-four hours to reach Europe. That the new jet could do it in eight, with only one stop at New York’s Idlewild, was a technological marvel, a magic carpet that Merritt couldn’t wait to experience. As someone who loved to go places, she knew it would change her life.

Many of the women Anne Merritt recruited for the trip were Jackie Kennedy wannabes, her Yankee-ness notwithstanding. Few American women, north or south, east or west, had failed to be captivated by Jackie’s accompanying JFK on a state visit to France, and the rest of Europe, in June 1961. The trip was extensively televised, and everyone was riveted. From the minute Jackie descended the gangway from the new 707 that had become Air Force One, and rode into Paris in her pillbox hat in a gleaming Simca cabriolet, it was clear that she had stolen the show from her husband. JFK admitted as much in his famous self-deprecatory introductory quote to the French, “I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris.” General de Gaulle was so taken by Jackie’s Miss Porter’s–perfect French and her grasp of the culture that at the Élysée Palace, he gushed, “She knows more French history than any Frenchwoman!”

In light of such glorious flattery, Jackie was unable to resist the siren call of French couture. Pressured by her husband to “dress American,” she had brought with her a gown by Oleg Cassini, the fashion designer big brother of gossip lord Igor. However, while preparing for the grand ball at Versailles’s Galerie des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors), Jackie was emboldened by a speed-laced “vitamin” injection from the family’s Dr. Feelgood, the New York physician Max Jacobson, who traveled everywhere with the Kennedys, dispensing medicinal fixes the way George Jacobs dispensed culinary fixes for Frank Sinatra. Suddenly, recalling the De Gaulle encomium, Jackie decided she had to play to the local audience, as well as to her French Bouvier bloodlines. Accordingly, she switched to her backup rhinestone-studded white satin gown by Hubert de Givenchy. When she rose at Versailles in Givenchy splendor to sing the French national anthem, it was the most rousing performance “La Marseillaise” had gotten since it stole the show in Casablanca.

That Givenchy moment stuck in the mind of the Atlanta belles, who were easy marks for Anne Merritt. Some of her friends had, like Jackie, gone to Vassar. More had attended Agnes Scott, the Vassar of the South, outside of Atlanta. Even if they hadn’t done their junior year in Paris, a year that made Jackie obsessed with all things French and fine, the ladies of Atlanta saw themselves as culturati. After all, they were the Art Association. Jackie spoke to them. Their good-old-boy husbands, a lot of whom were “rambling wrecks” from Georgia Tech or ex–big men on campuses like Charlottesville and Chapel Hill, may have preferred to stay home and play golf at Piedmont. However, they took a cue from President Kennedy and accepted the conjugal imperative. Merritt filled the charter in short order. Besides, the package—which the Art Association named “Trip to the Louvre”—was a good deal. Dossans, his airline, and American Express had come up with a bargain price for the monthlong tour, which included London, Paris, Amsterdam, Lucerne, Venice, Florence, Rome, and their own special visit to Versailles, for a rock-bottom $895. Normal first-class fare alone would have been $1,100.

For the independent travelers, who eschewed anything packaged and were confident to rely on that Bible of upper-bourgeois independent voyaging, Fielding’s Travel Guide to Europe, Dossans offered the Atlantans an air-only price of $388, compared to the $632 economy fare of the day. The independents would still get the inside track at the Louvre and Versailles, meeting up with their fellow Atlantans at the end of the trip for a Paris blowout. Arthur Frommer’s Europe on 5 Dollars a Day may have been infra dig for the Atlantans. But Fielding, basically Europe on 50 Dollars a Day, spoke the language of ritzy Peachtree Street. At $5 a day, the trip would have cost under $600, including airfare. That would have been beyond the dreams of the average American, whose median annual income in 1962 was $6,000. At the deluxe level of $50 a day, the monthlong trip would have cost $2,000. Coca-Cola executives were earning upward of $25,000 a year, as were the doctors and lawyers of Peachtree Street. At the top, then, these prices, for the trip of a lifetime (even factoring in inflation), were well within reach. Any way one went, travel then was a great deal, compared to the bank-breaker it would become. It paid to be a pioneer, a jet-setter even without one’s name in the columns.

Temple Fielding, the most trusted man in travel, the Walter Cronkite of tourism, was a highly acerbic exception to the gush-and-fawn corps of travel writers who tended to subsist on airline and hotel freebies. He was no fan of Air France. He renamed it “Air Chance,” justifying his anxieties by his observation that “on every flight I’ve taken with this line, at least one tray of champagne or still wine or cognac has gone up to the cockpit.” A chauvinistic American advocate of our “don’t drink and drive” ethos, Fielding wrote how he had approached Air France head honcho Max Hymans to discuss why French pilots were free to booze it up aloft while Americans were required to abstain from even a mug of beer within twelve hours prior to takeoff. Hymans’s arrogant retort was basically that French pilots don’t get drunk.

“He assured me that because the French pilot has grown up with wine,” Fielding reported, “ ‘a little wine’ [the quotation marks were a piqued Fielding’s] won’t hurt him during the flight.” This sent Fielding into one of his high dudgeons: “If Air France sincerely believes that the reflexes of their crews, after a glass or two of brandy or wine, are sufficiently razor-sharp to cope with instantaneous emergencies aloft, that’s their affair … I regret that it’s not the line for me.” The Atlantans may have been put off by Fielding’s warning, but they weren’t about to change their plans. The price was right, and the champagne-drenched French mystique, so heavily promoted in Air France’s “le bon voyage” advertising campaign, served to overcome any Fielding-induced trepidation.

The white, blue-striped Air France 707, named Château d’Amboise (the line’s 707s were all named after Loire châteaux) with 20 passengers in first class and 102 others in “tourist,” left Atlanta’s brand-new terminal on May 8, 1962. The plane’s name was pure Marie Antoinette, but the plane itself was pure Buck Rogers, endlessly long and sleek and a major step into the future from the boxier prop planes that had preceded it. The 707s were under three years old and still a novelty, though the local carrier Delta had recently begun flying the 707’s rival, the Douglas DC-8, on the Atlanta–New York route, so many of the Art Association group had already enjoyed the unique and overwhelmingly modern jet experience.

Everyone dressed for the occasion, the men in their Southern preppy best, blue blazers, ties, and straw boaters; the women in Jackie-esque pillbox hats, silk dresses, high heels, and because these were Southern belles, white gloves. All plane trips then were special events, this overseas departure even more so. Almost all the women were wearing corsages, farewell gifts from the large crowd of well-wishers who, in an age before security checks, streamed out to the tarmac and toured the 707 before takeoff.

Finally, friends and family retreated to the sides of the runway to watch the flying Château commence its mighty roar and takeoff to Idlewild. The flight would take an hour and a half, a seeming split second in those days when most Southerners went to Manhattan via overnight Pullman on the Atlantic Coast Line. The all-French stewardess staff served a picnic lunch of pâté et salade, and lots of Moët & Chandon champagne, splendeur en l’air, to be sure. The supposedly brief New York pit stop turned out to be a five-hour delay due to mechanical problems. Not wanting to spoil the multicourse gourmet French meal they knew was coming on the transatlantic leg, the Georgians trooped into the Idlewild bars and bided their time, hour upon hour, over peanuts and cocktails. By nine P.M., the Château had been repaired. The ladies slithered out of their girdles, kicked off their heels, and settled in for the flight and the night. Few could sleep. The 707’s launch campaign had stressed how “vibration-free” the jet experience was, eliminating the grind of the propellers, and how the new plane flew five miles “above the weather.” The Boeing people never mentioned turbulence, and the choppy spring jet stream kept most of the Georgians nervously awake throughout the seven-hour journey.

PARDON OUR FRENCH. A 1962 Air France promotion that fused French hospitality with American technology to entice tourists like those on the ill-fated Atlanta Art Association charter. (photo credit 1.2)

Morning in Paris was more than worth the nocturnal bumps. The weather was cool by Atlanta standards, in the midfifties, but the spring flowers were in bloom, and the sights were magical. Whether they took the tour or not, all the Art Association guests were treated to a complimentary night at the Hôtel du Louvre, across from the vast palace museum. Those lodgings could be had for around five dollars a night, and the more fastidious travelers could note that Temple Fielding didn’t even include the hotel in his guide. Such silence was not golden in a writer who cautioned his readers that the hotels he didn’t mention were “pretty grim,” and who trashed Sinatra’s—and Hollywood’s—favorite, the George V, thus:

… the connecting doors between some of the bedrooms are so thin that even private personal activities carry through them like paper; some of the staff, too, couldn’t seem to care less about answering that buzzer … I think that the George V is a very poor value for the money ($25 for a double)—but if you like the limelight and if you’re happy in a frenzied, F-sharp atmosphere, you’ll probably enjoy every minute of your stay in this hub of the restless American abroad.

Fielding was snide about the Jet Set’s go-to abode in Paris without actually using the appellation “Jet Set.” Fielding had his own words for the crowd, describing the grand hotel as “the French home away from home for the less self-conscious members of Broadway, Hollywood, Miami Beach and Main Street café society, most of them seeking lights, action and music in giddy determination.” As for less than grand places like the Hôtel du Louvre, which catered to package tours, Fielding had the most withering disdain:

Hoteliers in this city seem to spend their money on the ground floor, not in the bedrooms; upstairs you’ll often find peeling paint, frayed carpets, screamingly lurid French wallpaper and toilet facilities that are so chummy, cozy and nonchalant that you’ll either turn pale in horror or burst out laughing.

The group had no time to dwell on the shortcomings of their lodgings. They were whisked off by an American Express guide to the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa, the Winged Victory, and the group’s favorite, Whistler’s Mother. Then they were herded onto a tour bus to see Paris by Night and dine in what their trip brochure described as a “typical popular restaurant.” The usual go-to of American Express was Au Mouton de Panurge, an urban kitsch farmhouse on the right bank near the Opéra, complete with wench-waitresses in medieval costumes and live sheep grazing about. The restaurant, inspired by Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel, had been around since the thirties and was testimony to French intellectualism; even the tourist traps had literary antecedents. This one rubbed its customers’ faces in it. The restaurant was named for a Rabelaisian sheep who followed other sheep off a cliff without regard to the disastrous consequences. Sort of like tourists flocking to a bad restaurant because lots of other tourists were there. Fielding described the ambience as “startlingly pornographic,” with phallic-shaped rolls and escargots served in replicas of chamber pots. He hated the food, which cost a steep $10 a head. Even worse were the boisterous and non-French clientele. There were “so many Americans,” Fielding wrote, “I could shut my eyes and swear that I was back in Howard Johnson’s.”

After the first night, the tour left for the English Channel boat train to London, while the independents checked out of the Louvre and in to Fielding-approved caravanserais, where they followed the Fielding program of restaurants, nightclubs, and shops (he barely mentioned museums) designed for his tourists to feel vastly superior to un-Fielding tourists. Fielding gave his readers the names of the owners of these places, the concierges and maître d’s, and insisted the readers drop them like crazy. Royal treatment would be assured.

Fielding’s number one Paris gourmet pick was the Tour d’Argent, which had been founded by the proprietor of the George V, André Terrail, one of the giants of French hospitality and the favorite of tout Hollywood. His son, Claude, the current patron of the Tour, had become part of filmland’s inner circle by having been the lover of Ava Gardner and Rita Hayworth, then marrying the daughter of movie mogul Jack Warner. It was the one restaurant in Paris that could lure Sinatra away from Campbell’s, and similarly, it was able to lure American tourists, such as the Georgians, away from their steaks and Scotch. For under $10, including fine wine, it was easy to be seduced by the Tour, especially if you could see Sinatra, or Audrey Hepburn, or Gary Cooper, or Jackie herself, across the dining room, silhouetted against the restaurant’s iconic vista of the flying buttresses of Notre Dame. Small wonder the Fielding Guide became a must for the well-off traveler and, updated annually, sold in the millions.

However they traveled, organized or independent, all the Atlantans had a wonderful month of May. Some of those who didn’t take the tour had done the highlights before and now went as far afield as Greece, Egypt, and Israel. They all reassembled in Paris on May 30, loaded to the gills with treasures from across the Continent. Their common concern was how to circumvent the low $100-per-person customs exemption. Some spent their remaining four days in the City of Light at the post offices, dividing their spoils into many packages with low declarations, and shipping them to a lot of varied addresses, to beat the duty.

Otherwise, they took Paris by storm, eating, drinking, shopping, but always putting culture first. They went back to the Louvre and savored a perfect full day at Versailles, made more memorable by the presence of a large troupe of thespians dressed in Louis XIV regalia, shooting a film called Angélique and the King. The actors and actresses of this French costume epic, starring Michèle Mercier and Jean Rochefort, posed with the Atlantans throughout the palace. What photos they had to show the folks back at home.

Finally, it was time to go. June 3, 1962, was a glorious Sunday, cloudless blue skies, a brilliant sun. It was a perfect day to fly. But it was also a perfect day for Paris. A lot of Georgians hated to leave, hated to go back to hush puppies and Cokes after croissants and café au lait. How, indeed, were you gonna keep ’em down on the farm, or even the new Lenox Square Mall, the grandest shopping center in America, after they’d seen Paree? They took one last glance at the Eiffel Tower and wistfully filed into the American Express coaches that transported the group, past Notre Dame, past the Île Saint-Louis, past the Tour d’Argent, out to the gleaming modern American-style terminal at Orly Airport to board their return chartered 707. This one was named the Château de Sully and was designated Air France Flight 007. Dr. No, the first of the James Bond series films, would not debut until October of that year in England, the following year in America. But several of the men in the group were fans of the Ian Fleming books, inspired perhaps by big fan John F. Kennedy, and in light of their recent transcontinental derring-dos, they may have made some hay of the jet’s secret agent–sounding appellation.

Paul Dossans had flown over from Atlanta just to make sure the trip ended well, and was flying back with the Art Association. The goodwill and word of mouth his brainstorm promised to generate was enormous, guaranteeing Air France a special place in the heart of haute Atlanta and hopefully giving it a big leg up against rivals Pan Am and TWA. One of the group’s couples, who had three young children, insisted on traveling on separate jets. The wife was on the charter; the husband had booked a later Pan Am flight to New York, where he would switch to Delta and fly home. Dossans tried to talk him out of it. But the husband was too superstitious to change his plans.

The captain, thirty-nine-year-old Roland Hoche, personally welcomed each of the Atlantans onto his gleaming Château, which was only two years old. Dedicated to charter-only service, the Château de Sully had logged only five thousand flight hours, mostly carrying tour groups like this one across the Atlantic. There were seven French flight attendants, two in first and five in tourist. Hoche announced that the estimated flight time to New York would be a speedy seven and a half hours. There were no major headwinds expected. The stewardesses poured the champagne, and the Atlantans took one last look at the green French countryside. But it wasn’t adieu. It was à bientôt. Everyone couldn’t wait to come back. How could they not? It was cheap. It was fast. It was easy. It was Europe.

The Sully got off to a late start because several of the group lost track of time making last-minute purchases in the duty-free stores. Dossans combed Orly and rounded up the dilatory shopaholics and herded them to the jet. The stewardesses cosseted travelers with International Herald Tribunes and fine chocolates, made sure they were belted in, and recited safety instructions that no one was listening to. Then Hoche pulled back from the terminal and took the Sully to Runway 26 for takeoff. The Georgians had a number of friends at Orly saying goodbye, who watched the Sully start to accelerate. While the roar was mighty and the speed was lightning, the plane seemed to be taking too long to rise into the air. Finally, it did lift off, but only a few feet.

Then the Sully, hurtling toward the end of the runway, tried to stop. The reverse thrust and screeching brakes, sounding like a thousand banshees, were unable to stop the 140-ton craft. The runway ended and the Sully hurtled into a green field in the adjacent hamlet of Villeneuve-le-Roi. There it careened wildly. Upended, one of the wings hit the ground, and the plane began breaking apart. When the jet engines hit the earth, there were several massive explosions as the twenty thousand gallons of jet fuel ignited.

The Sully went up in what looked like a nuclear blast that disintegrated most of what was left of it. The thick black smoke was a miasma blotting out the bright sun. It was springtime, but it looked like autumn, when the fields were burned. One house nearby caught fire. But the residents were away. Miraculously, no one in the village, many of whom were enjoying Sunday picnics in the countryside following a parade honoring the 1944 liberation of French prisoners of war, was harmed. The Villeneuvians were inured to the noise of Orly. But they had never seen a crash, not like this. No one had. The failure of the Sully was the worst single-plane disaster in the history of aviation to that day.

One hundred thirty people perished. Only the two stewardesses and one steward, sitting at the tail of the plane, survived, having been hurled from the wreckage before the explosions. Everyone else was obliterated, the French crew, the Georgians, and Paul Dossans, who had striven so mightily to make everything on the “Trip to the Louvre” be perfection. Atlanta had not been so devastated since Sherman’s March. The city was in shock, too dazed to mourn. Its progressive Kennedy-esque, newly elected mayor Ivan Allen dropped everything to fly via New York to Paris and help identify the bodies, if such a task were possible. Many of the dead were his good friends.

Despite the tragedy, Allen was not one to blame Air France. In fact, he took the New York–to–Paris Air France flight, on which the captain invited him, his deputy mayor, and his press secretary to spend an hour in the cockpit and see the marvel of technology firsthand. The horror was brought home at Orly when French authorities, led by an emissary of President de Gaulle, gave Mayor Allen and company a tour of the wreckage, the Sully’s intact tail section standing sentinel over the still-smoldering carnage. The bodies may have been burned beyond recognition, but a lot of the inanimate objects remained. Allen spotted a necktie he had given one of the passengers as a Christmas gift. He recognized mink stoles, party dresses, necklaces the women had worn to dances at the Piedmont Driving Club. He saw labels from Atlanta’s top stores. But he couldn’t see his friends.

The darkest commentary on the dark day came from sunny Los Angeles, where Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X literally jumped for joy at the tragic news. “I got a wire from God today,” he exulted to his audience, “well, all right, somebody came and told me that he had really answered our prayers over in France. He dropped an airplane out of the sky with over 120 white people on it because the Muslims believe in an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. But thanks to God, or Jehovah, or Allah, we will continue to pray, and we hope that every day another plane falls out of the sky.” Malcolm X was denounced by Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty as a “fiend,” which only added fuel to the fire and succeeded in getting X the front-page recognition he had been seeking. The Atlantan Martin Luther King, Jr., was appalled. Reverend King had been working hand in hand with Mayor Allen, a born-again integrationist, to change the ways of Atlanta. This was not his method.

Frank Sinatra was in London when the crash occurred. He had flown there from Rome in El Dago (now Christina) to stay at the Savoy and do a benefit command performance for Princess Margaret at the Royal Festival Hall. At the Hall, he did a thirty-song set, culminating in “Come Fly with Me.” And then he flew off to Paris, to the George V, to prepare for shows at the Olympia Music Hall and at the Lido, flanked by the super-cabaret’s Bluebells, Paris’s topless answer to Radio City Music Hall’s Rockettes. The first Lido show was June 4, one day after the Sunday crash, and it is notable that “Come Fly with Me,” Sinatra’s standard closer, had been dropped from the playlist. Sinatra concluded his performance with “The Lady Is a Tramp.”

It had been a terrible period for the 707, which had gone for its first two years without a crash. The bad luck started in February 1961, when a Sabena 707 en route to Brussels from New York crashed on landing at Brussels, killing seventy-two, including the entire American figure-skating team, traveling to the world championships in Prague. In March 1962, an automatic-pilot defect caused American Airlines Flight 1, from New York to Los Angeles, to crash into Jamaica Bay on takeoff, killing several major tycoons, including hotel magnate Arnold Kirkeby and oil magnate W. Alton Jones, a close friend of President Eisenhower. A $10,000 bill was found in Jones’s wallet. Sinatra had even more doubts about flying commercial after that one.

On May 22, 1962, when Sinatra was performing in Rome, Continental Airlines Flight 11, going from Chicago to Kansas City, exploded over Centerville, Iowa, killing all forty-five people aboard. At first it was suspected that the plane had been downed by heavy thunderstorms. However, an investigation led to the discovery of sabotage. One of the passengers had bought $300,000 of insurance right before the flight. He had also purchased six sticks of dynamite for twenty-nine cents apiece. He jerry-rigged a bomb and planted it in the 707’s rear lavatory. The bomb worked. So did the plot, which became the basis of Arthur Hailey’s 1968 bestseller Airport.

And now, less than two weeks later, the Château de Sully became the fourth ill-fated 707. Once Atlantans recovered enough, people began speculating. Some articulated the Temple Fielding “Air Chance” notion that the crew members were drinking before takeoff. But the predominant hypothesis was that the Art Association voyagers were victims of their own acquisitiveness. Because the Sully was a private charter, baggage weight restrictions may have been honored in the breach. Despite enduring the long lines at the Paris post offices to minimize customs duties, the Atlantans may have been carrying back so many antiques, paintings, and clothes that, combined with the heavy fuel load to make it across the Atlantic, and the full capacity, the Sully could have been a victim of its own weight. The Art Association may have literally “shopped till they dropped,” a ghastly possibility.

It wasn’t until 1965 that the seemingly endless investigation of the Sully crash was concluded. In February of that year, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) issued its long-awaited report. The lawyers for the decedents’ families were already in a legal war with Air France, hiding behind the shield of the pre–World War II Warsaw Convention, which capped any family’s recovery at $8,291. This added up to under $1 million for the whole plane. The plaintiffs’ lawyers were seeking upward of $20 million. The ICAO’s report was curtains for Air France, which was blamed for both pilot error and mechanical failure (of something called the trim tabs, before the name was commandeered by a vitamin company). The litigation dragged on for several more years until, after the death of the plaintiffs’ lead counsel, his successors quietly settled with Air France for around $5 million, or about $85,000 per family. It was the largest settlement in history for a single airplane crash, but to the victims’ families, it seemed like peanuts.

The government of France, knowing it had gotten a great deal, tried to make it up to Atlanta by donating a Rodin sculpture to become the centerpiece of the city’s new Municipal Arts Center, opened in 1968 as a memorial to the Art Association victims. The statue was called L’Ombre, or The Shade. In his presentation, the French ambassador described the Rodin as “a reconciliation of death and destiny.” Atlantans, famed for their courtesy and Southern hospitality, accepted the goodwill gesture and refrained from blaming France or its airline. The premier exhibit of the new High Art Museum was a tribute called “The Taste of Paris,” featuring three centuries of art loaned by French museums. The “Trip to the Louvre” would never be forgotten.

As for Frank Sinatra, the ultimate Jet Setter kept on jetting, albeit privately and nervously. He stayed off Air France. He stayed off Pan Am. If he needed a 707, he would charter it and do it “his way.” In 1964, he signed a contract with the Learjet Corporation to buy one of their first-generation private jets. Lear congratulated Sinatra on purchasing “the world’s finest business machine.” By 1964 Sinatra, nearing fifty, was chairman of Reprise, his own record label; he also oversaw his film company, his huge real estate holdings, and a major investment in a missile parts manufacturer. Sinatra was now a Big Businessman, and a Learjet, the ultimate corporate tool, was as natural a component of his portfolio as his cellar full of Jack Daniel’s. He tastefully named the Lear the Christina II. The Hoboken swagger had been replaced by a Wall Street stride.

Not that the Rat Pack party days were completely behind him. He used the Lear—which seated only six and had no bar—mostly to shuttle his pals between Los Angeles, Palm Springs, and Las Vegas. For the long hauls and the concert tours, he still chartered the big 707s. But he loved showing off the Lear as the party favor for a Hollywood that had everything. He flew a wide-eyed Mia Farrow on it to Palm Springs for their first date, and to the Côte d’Azur for their 1966 honeymoon. He snowed Michael Caine, when Caine was dating Sinatra’s daughter Nancy, by Lear-ing him to Vegas, just the two guys, heart-to-heart, to make sure Caine’s intentions were honorable. Sinatra assumed that the truth would be spoken at 30,000 feet. Sinatra lent the Lear to Sammy Davis, Jr., and Marlon Brando to fly to Mississippi to join Martin Luther King, Jr., on a freedom march. He lent it to Elvis Presley, whom he once despised as vulgar but came to embrace, for the King and Priscilla Beaulieu to fly from Palm Springs to Las Vegas to get hitched by a justice of the peace. He lent it to the Beatles. And in 1967, having been instrumental in making the Learjet the millionaire’s favorite status symbol, he sold it, trading up to the new Gulfstream GII, which did have room for a bar, though not as big as El Dago’s. By now the chairman was drinking less. In 1972, he bought his very own 707, one originally built for Australia’s Qantas.

In January 1977, the ultimate irony befell Sinatra. He was about to fly his entourage on his current jet from Palm Springs to his opening night at Caesar’s Palace. But his beloved mother, Dolly, visiting from New Jersey, couldn’t stand Sinatra’s new wife, Barbara Marx, and refused to fly with her. So Sinatra simply chartered Dolly her own Learjet for the twenty-minute flight to Las Vegas. The plane was overflowing with a cornucopia of luxury food and amenities, as if destined for Paris.

It was one of those rare winter days when it was cloudy in Palm Springs. The pilot, who had flown the short route countless times, was undeterred. But, like the pilot of the Château de Sully, this pilot was in error. The clouds became a blinding blizzard, and the Lear crashed into the massive Mount San Gorgonio, instantly killing Dolly, her friend, and the Lear’s crew.

The pallbearers at Dolly Sinatra’s funeral included Frank’s old flying buddies Jimmy Van Heusen, Leo Durocher, and Dean Martin. Frank was so traumatized by the loss that he reembraced his long-lost Catholicism and forced his wife, Barbara, to convert. But no religion could restore his shaken faith in private jet aviation, or his faith in himself as always being in control, that his way was the safe way. He could never believe that the anxieties he’d fought so hard could come true, that a Sinatra could die in a plane crash. “She was a woman who flew maybe five times a year,” he mumbled incredulously to the press. “I could understand if it happened to me …”

But that tragedy was decades away. At the dawn of the jet age, the utter glamour and flash of Sinatra’s own historic “Come Fly with Me” spring tour ultimately proved to be an effective counterweight to make the world forget the disaster of the Atlanta “Trip to the Louvre.” It transformed 1962 from what could have been an annus horribilis into what Sinatra would deem “a very good year,” emblazoning the concept of the Jet Set in the public consciousness and inculcating a national belief in another famous Sinatra lyric, “Fairy tales can come true, they can happen to you.” Nevertheless, there was a nightmare of fiery destruction lurking in the wings, the specter that the magic carpet of jet travel could unravel. It was the genius of the airlines, the myth-making machinery, and the power of positive thinking, that the Jet Set, and not fear of flying, took a pole position in the sixties’ version of the American Dream.