3.

ASK ME ABOUT MY VOW OF SILENCE

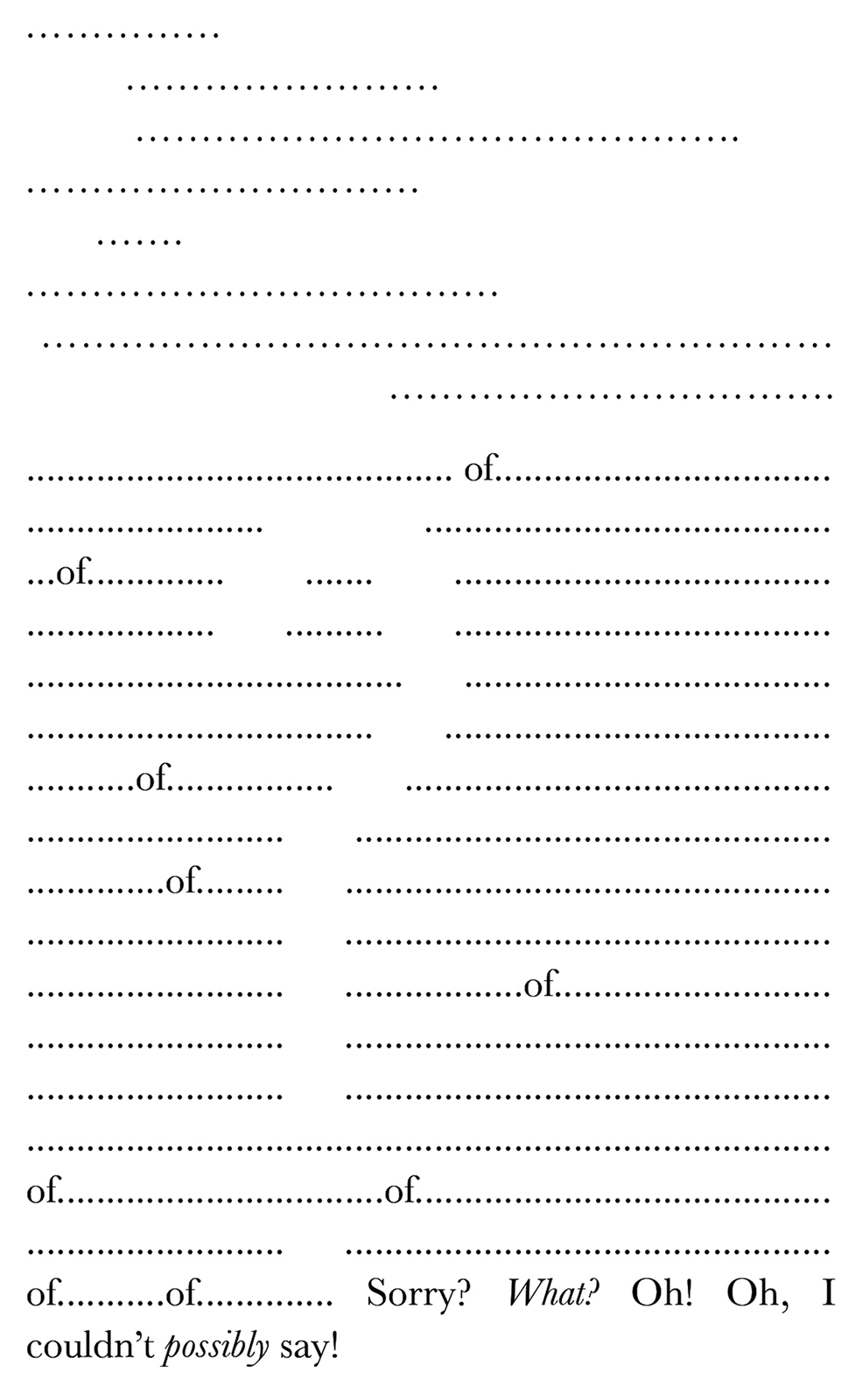

Avigail is – and has always been – fascinated by the power of silence. Over time this fascination has expanded – quite naturally – into an important, secondary belief in the comparative pointlessness of words. She quickly noticed how her sole designation in the noisy, chaotic home of her childhood (as the middle child of five) was simply to peep-peep-peep like a bird. She’d open her mouth to speak (that deep inhale on the cusp of the first syllable) only to be stuffed full of worms (and ignored). Children, she discovered, were sometimes listened to yet rarely heard.

And the emotions? Fruitless things – hurtful, burdensome things – always standing in the way of progress.

Another revelation was her capacity to befriend – better still, to harness – the very thing that was once imposed (un-heard-ness). Her power – such as it was – quickly became a defiant holding-in. A refusal to engage. But expressed so meekly, at first. A gently tipped head. A cocked ear. Ah, to hear! To listen and remain quiet. To be lost-in-your-own-thoughts but still in charge of the map of meaning. To dumbly observe. To be hush hush hush! So exquisitely small! To take up such a tiny amount of space. To be so thoroughly modest and discreet and unassuming and … and … la femme n’existe pas … il n’y a pas la femme.

There is so much room in silence. It’s so generous! It expands around you like a giant woollen blanket. Soft wool. Cosy. Quiet wool. Ah, the gorgeous feeling of semi-breath-holding. The sensual alertness of not. The resigned sigh of shhhhhh. The regretful silence. The watchful silence. The keen silence. The ambiguous silence. The mystery of silence. The infinite possibility of silence.

Everything so subtle. So gentle. Nothing stated, everything suggested.

Oooh, and the naughty waywardness of simply pointing, dumbly, when you could speak, but choose not to …

Avigail learned how to own her silence – how to protect it and to nurture it. She loved it. She hated the leaving of it – the bored croak of speech, the sudden colour and hurt and smash of language. Silence was thick, smooth cream. Words were a furious, fiery chilli sauce that hissed and raged and burned on the throat.

She once read a quotation by Max Picard about animals and silence: about how animals carry around a dense silence within them on behalf of man. Of how they are constantly placing down this silence in front of man.

A gift. An offering. A hope. A burden. A rebuke. An expectation.

Ahhh. Silence.

The thrill of it.

Avigail suspects that the great mission of her life will be to one day discover the full extent of this strange gift of hers – this amazing aptitude – for quiet. To test the seemingly endless parameters of …

Ah, this calculated regression!

This unanswerable no!

Although before all that, she needs to stop trying so determinedly to be normal.

But she’s worked so hard for it – starved for it. So she can’t relinquish it. She must keep on pretending because she is so proud of her adaptation, of how good she has become at fitting in.

Seriously!

You would never know what a freak she truly is!

Surreptitiously.

Hidden away.

Underneath.

Perhaps the performance (the normality) is merely the set-up, and the punchline, the denouement, is unpronounced, is wordless?

Jouissance.

Even in the midst of tumult, there is quiet.

It hides in the top of her head. It is like a little golden frog, perpetually waiting to jump. It is ever watchful but makes no decisions. There is no ‘do’ or ‘don’t’ here, no moral imperative. It is thoroughly dispassionate.

Tranquil.

‘How about the tiles?’ Charles asks. ‘Do you like them?’

Charles’s question can barely be heard above the desperate, harsh bark of Wang Shu’s laughter.

Avigail stares at Charles, dumbfounded.

Wow.

Wow.

He really is a piece of work!

She replaces the silver cream jug (and the menstrual tea) back on to the refrigerator, then picks up the broom, the T-shirt (which Morpheus has happily relinquished) and retrieves Wang Shu’s phone. She tries to pass Wang Shu the phone but Wang Shu is disabled by laughter. She has temporarily lost the use of her eight fingers. And her two thumbs.

Charles is now attempting to show Ying Yue the tiles, clearing away some of the assembled detritus. The tiles are quite repulsive. Over the terrifying howls of Wang Shu’s laughter, Charles is pointing at the tiles and saying, ‘These are the work of a celebrated designer called Alan Wallwork. My mother was very attached to them. It would be a great shame if whoever buys the house …’

Ying Yue is pinching her tiny, hardly chin and listening intently while nodding, thoughtfully.

‘Beautiful!’ she eventually pronounces.

Wang Shu suddenly stops laughing. Avigail (relieved) tries to pass her the phone again but Wang Shu flinches at Avigail’s approach. Ying Yue (fighting the instinct to mirror) puts out her hand for the phone.

‘Mother is afraid of the broom,’ she gently explains. ‘Being hit by a broom is very bad luck to a Chinese person and you were hit by the broom.’

Avigail is perplexed. ‘So the broom is bad luck? Or am I now bad luck because I was hit by the broom which …?’

She is going to say ‘which you knocked over’, but resists the urge.

This is crazy.

She hands Ying Yue the phone.

Rather than answering Avigail’s question, Ying Yue says something, brightly, to Wang Shu, in Chinese, while pointing to the wall tiles.

Wang Shu (like a toddler who has been momentarily distracted from its tantrum by a small bag of Cadbury’s Chocolate Buttons) gazes at the tiles for a brief instant and then lets forth a loud stream of invective. Wang Shu plainly hates the tiles. The tiles have now come to represent everything about the falling broom that cannot be fully articulated in a European context. Ying Yue knocked the broom so is in disgrace. But the broom hit the Agent (Avigail). Yes! The broom hit the Agent! The Agent is jinxed! The viewing is jinxed. Then the Agent – with a complete lack of consideration and due care – allowed the broom to hit her toe! Wang Shu’s toe! So Wang Shu’s toe is jinxed! Which is horrifying! And disgusting! And the tiles are vile! Damn the tiles! They are jinxed. They are malodorous. They are despicable! The tiles are among the most revolting things Wang Shu has ever beheld in a life where much that is revolting has been beheld.

Wang Shu loathes the tiles.

Wang Shu continues this terrifying tirade, her lips flecked with spittle, her fists clenched (sometimes a fist briefly unclenches so a finger may point at her toe, then clenches again), for approximately a minute and a half.

When Wang Shu finishes speaking she promptly bursts into angry tears.

Yes. That’s how deeply, deeply offended Wang Shu’s very essence – her very core – is by the Alan Wallwork tiles.

Ying Yue bites her lip. Avigail looks at Charles.

Her eyes say: What the fuck?!

Charles shoves his hands into the pockets of his jeans.

Wang Shu’s phone rings. Ying Yue immediately hands a sobbing Wang Shu the phone. Wang Shu takes the phone. Wang Shu instantly stops sobbing. Wang Shu answers the phone.

‘Ni hao?’

Priorities.

Ying Yue promptly turns to Charles, her eyes dancing.

‘Mother loves the tiles,’ she beams.

Richard Grannon’s sister once shared a piece of hippy-dippy shit with him – years ago – which he instantly discounted (having a residual suspicion of all things New Age) but later (against all his better instincts) felt compelled to re-evaluate, and then, eventually, to integrate it into his groundbreaking Inner Critic work. For no other reason than that it made a stupid kind of sense. Grannon’s sister had learned this piece of wisdom from someone selling crystals at a festival (or a yoga teacher). It was presented in the form of a question. The question ran as follows:

‘What is the story that you are living now about this situation?’

Again:

‘What is the story that you are living now? About this situation?’

Is your truth simply a fiction?

Is the story that you are telling yourself – this flimsy, fragile, hashed-together fragment – all that you truly have?

If your answer to the last question is in the affirmative (and Charles’s jury is currently still out on this), then it definitely needs to be a good one (a good story).

If the story is all you have –

then it needs to be a great story.

Charles looks at Ying Yue and he thinks, What is the story that you are living now about this situation?

Ying Yue must be aware of the fact that he is aware of the fact that she is lying about Wang Shu’s feelings with regard to the Alan Wallwork tiles, but still, still …

What is Ying Yue’s story? What story is she living now?

?

These people are morons?

If I just say the right things – make the right noises – it’ll all be okay?

The world is simply a wild and delirious phantasm (and I am a little feather floating though the cosmos)?

Charles scowls, and then wonders, What is the story that I – Charles – am living now about this situation?

Uh …

These people are morons?

If I just say the right things – make the right noises – it’ll all be okay?

The world is simply a wild and mysterious phantasm (and if I could simply find the perfect toaster/kettle/juicer it’ll all be dandy)?

How odd that he and Ying Yue (this strange, bedraggled, ill-drawn creature; this girl, part-stuffed, badly sewn, full of otherness) might actually be spinning the same story.

No!

No!!

Surely not?

He gazes at Ying Yue, owlishly.

There is something so plain, so empty, so smooth about Ying Yue’s face that it is almost otherworldly. It is the face of a mammal, though. Yes. Just about. Ying Yue is a mammal. But oceanic. Cetacean. More like a dolphin than a person. Giant forehead. Tiny, friendly eyes. Dolphin smile. No chin. And her torso. Dolphin-shaped. Little arms like flippers.

Charles focuses in on Ying Yue’s bandaged flipper.

‘What actually happened to your flipper?’ he wonders.

‘Sorry?’ Ying Yue’s smile wavers.

Charles starts.

DID I ACTUALLY JUST SAY THAT?!

‘ WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED TO YOUR FLIPPER?!’

DID I ACTUALLY JUST SAY THAT?!

Out loud?!

‘Have you ever considered covering your drying rack with a sheet?’ Avigail interrupts. She is re-hanging the arm bears T-shirt. The offending broom has already been placed neatly out of harm’s way. Avigail has a terrible feeling that the oyster shell hit and the broom fall may now spell disaster for the sale.

Yes.

Um …

Hang on a second …

Did Charles (illumined Charles) actually just utter the word ‘flipper’?

Flipper?!

Avigail tries to re-run Charles’s last sentence in her mind with a series of other words replacing flipper. But she can’t. There aren’t any other words to replace ‘flipper’.

Hipper.

Chipper.

Clipper.

Tipper.

Flipper is a fairly particular word.

She visualises her commission going up in smoke.

Pouf!

Charles should actually be issued with a public health warning.

Charles is a fucking menace.

Flipper?!

Ying Yue touches her bad arm with her good hand and opens her mouth to speak but then defers, automatically, to Avigail.

Yet underneath …?

She is seen!

Ying Yue is seen!

And with flippers!

Ying Yue’s spirit animal is the dolphin.

Ying Yue is seen!

By this strange-looking gentleman with his long, pale face and his holey, black underwear!

Flip-pers.

What mean this word?

La la la.

Charles glances over at Avigail.

What is the story that Avigail is living now about this situation?

he wonders.

Avigail is actually quoting the Tao Te Ching to herself.

There is no calamity

Like not knowing what is enough,

she thinks.

Fuck you, Charles,

she thinks.

Flipper?

she thinks.

The oyster shell?

she thinks.

The broom?

she thinks.

Avigail is living at least five different stories. And they are all running in her head, consecutively. And none of them fit perfectly together or make absolute sense.

But that’s okay.

Yup. That’s absolutely fine.

Because good enough is more than enough. For Avigail.

Ha.

Yeah.

If only.