5

FIELDWORK IN ARCTIC ALASKA

On a sunny evening in the summer of 1948, on the east shore of a small lake eighty-four miles northeast of Nome, Alaska, four men and a dog sat on the ground in the lee of a white canvas wall tent. Nearby, a fifth man busied himself skinning a rodent. The four men played bridge but, like the dog, were alert for any sound indicating the near availability of food. The fifth man, Bill Quay, the camp cook, went about his business unhurriedly, more intent on peeling the skins from voles and lemmings than from potatoes and carrots. Quay was a mammalogy student. He dug pit traps around the camp and collected small mammals: shrews, lemmings, voles, and an occasional ground squirrel. These he skinned and prepared as study specimens. He was usually still at this task when twenty-six-year-old Dave Hopkins and his USGS field crew tromped into camp in the early evening, exhausted and ravenous. For a couple of hours, while they waited on dinner, the men played bridge and voiced their suspicions as to the probable rodent content of the stew in progress. When it finally arrived, they were grateful for chunks of meat and fat, whatever their origin.

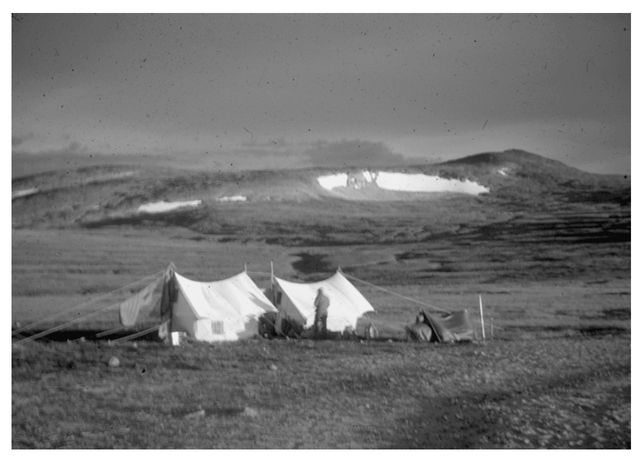

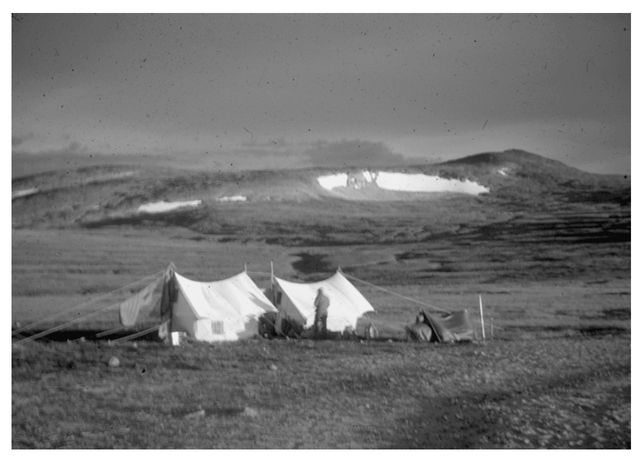

Tents in a big wind at Lava Lake, July 4, 1948 (Photo by Dave Hopkins, courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

After sitting nearly idle in Nome for the better part of June, Hopkins could write home on the thirtieth that he had finally been able to get an Army PBY floatplane to haul the field crew to Lava Lake and was “in the field at last.” Wading ashore with their gear, the crew found a cache of old oil drums, canvas, tent poles, and wooden boxes—remnants of an earlier encampment of a small detachment of Army weathermen. They set up an eight-by-ten wall tent for the kitchen, and pitched two more eight-by-eight tents for sleeping quarters. As a cache for the grub, they arranged the oil drums into four walls and roofed them with boards and canvas. Where a little creek flowed toward the lake, Quay built a dam and rigged up a stove pipe flume leading to a big washtub, thus providing running water to the middle of camp. Ingenuity was at work at the other end of the water cycle, as well. The deluxe latrine featured, over the customary hole in the ground, the upper portion of a pot-bellied stove with the lid removed. A superstructure of two-by-fours supported walls of mosquito netting, but “the resulting cage,” Hopkins wrote, “was an atrium for a thousand mosquitoes, rather than a sanctuary for humans.”

A pair of muskrats lived near camp and liked to climb up and wash themselves on a dock built of oil drums and planks. But the most bountiful wildlife was the nesting migratory birds. “Whenever I sit down to take notes,” Hopkins wrote home, “I am surrounded with chipping and chirping birds appearing from every bush and tussock.” He noted tiny red-polls and white-capped sparrows, longspurs with their black throats and rusty collars, yellow wagtails, tawny willow thrushes and some kind of warbler. “Every patch of brush,” he wrote, “is noisy with the fluttering of wings.” The lake drew in waterfowl too: oldsquaws, eiders, scoters, scaups, and loons. “I’m seeing swans daily—they’re graceful flyers and the first thing I notice is the sound of wings and a very high soprano croak, and then I see them drop into some nearby lake.” Canada geese gathered in noisy conventions on the Noxapaga River just west of the lake. Ptarmigan and snipe inhabited the uplands; while marauding jaegers patrolled overhead, always ready to destroy a nest of eggs or pick off a young bird. Higher still, in the outermost orbits of the winged world, the watchful eagles drifted.

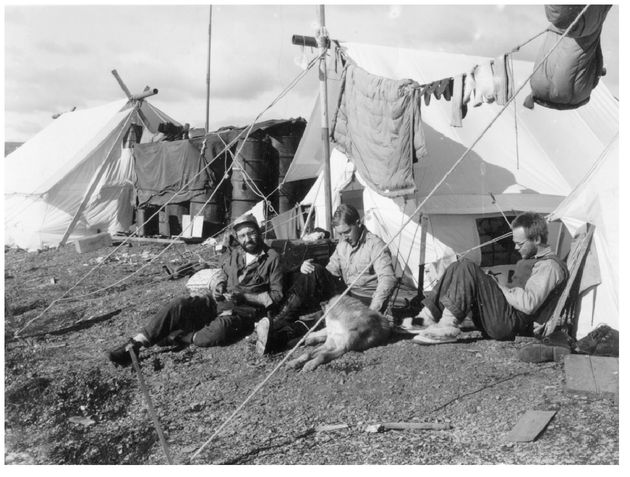

Sigafoos, Hopkins, and Fernald building the meat cache at Lava Lake, 1948 (Courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

D. O’Neill

When recruiting crew members for summer fieldwork, Hopkins could be a bit zealous in his quest for diversity. Even the cook had to contribute to his widening interests. One year, when he was leafing through a big stack of Form 57s, the federal government’s personnel form, he spotted an interesting cook prospect. Two things caught his eye: The fellow was Iranian-born, and he answered yes to all the questions that asked whether his history contained instances of moral turpitude or affiliation with the Communist party. Hopkins hired him at once, anticipating dinners of spicy kabobs and provocative political conversation. At that summer’s field camp,however, he discovered that the fellow’s inclinations—both gastronomical and philosophical—were mild to the point of bland. Discreetly, Hopkins probed. It turned out the cook was the son of a missionary, hence the Iranian connection and perhaps the mainstream politics. As for moral turpitude and Communist leanings, he said he’d become impatient filling out the government’s long personnel form. After plodding through a series of questions that all called for an affirmative response, he’d simply run down the rest of the list checking all the yes boxes.

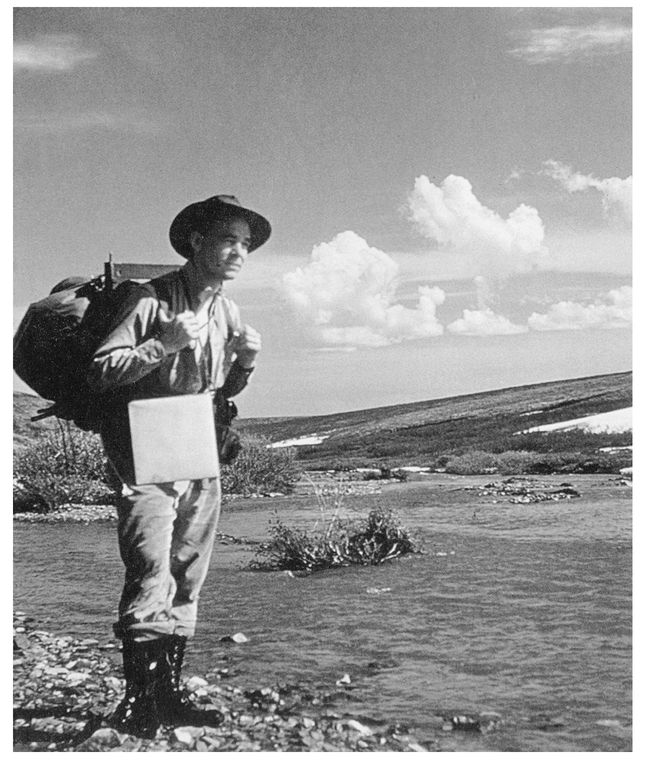

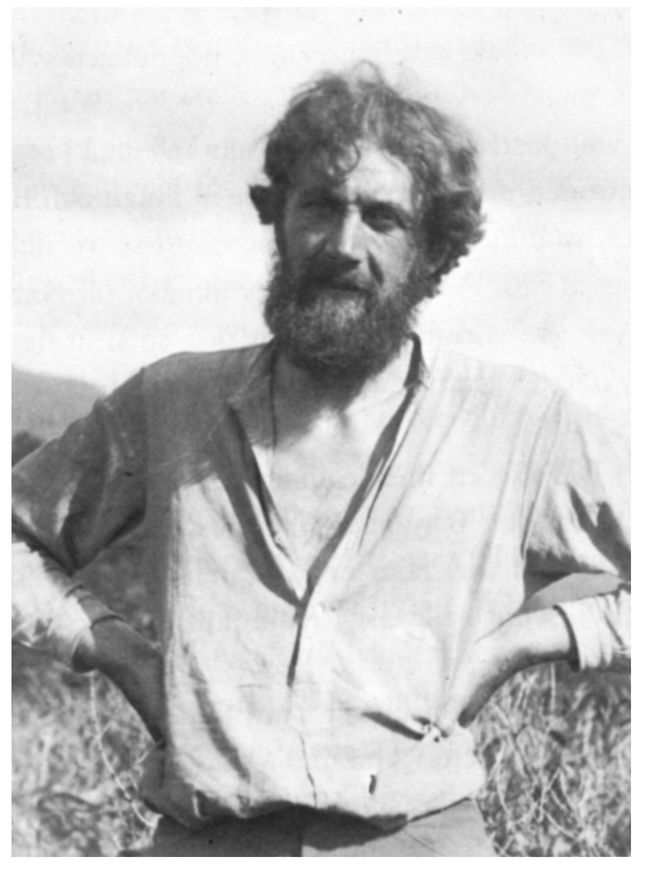

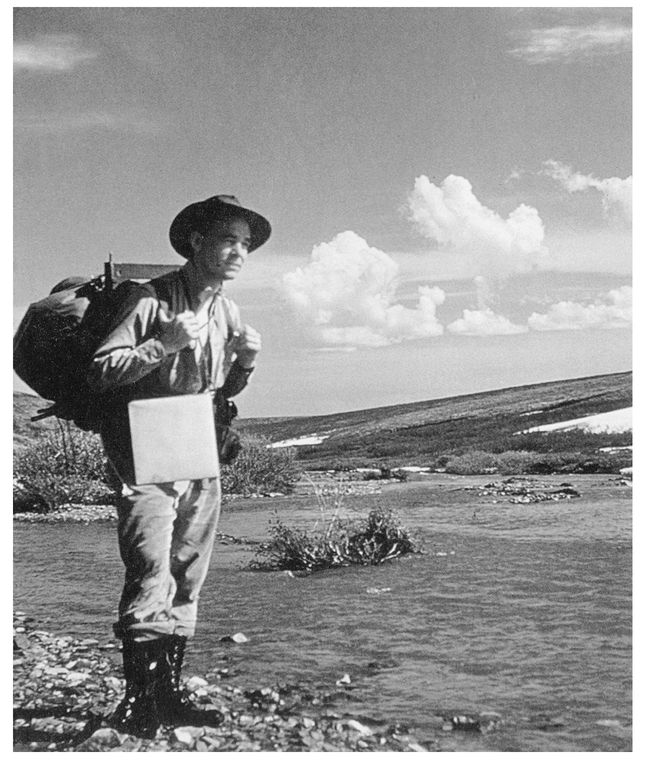

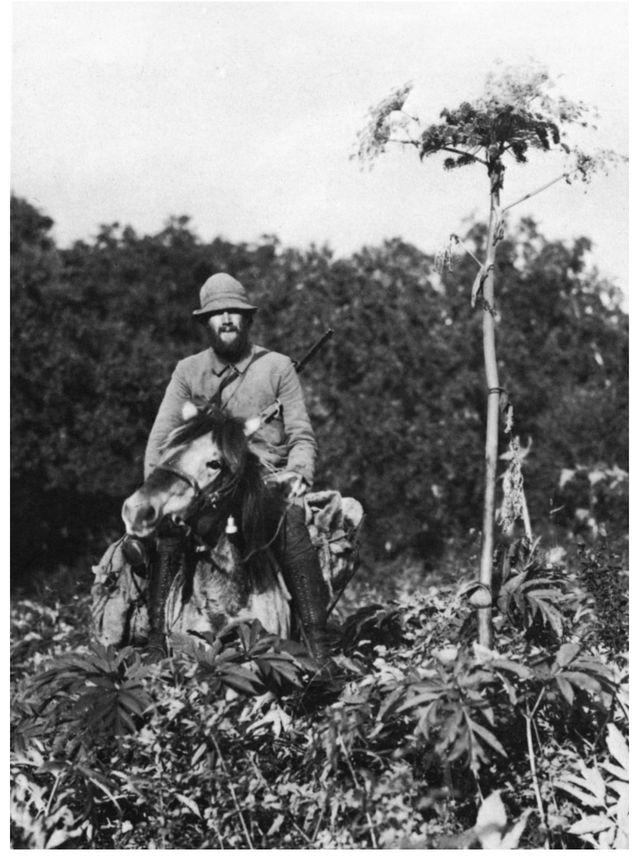

Hopkins at Hammum Creek, near Imuruk River, 1948 (Courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

For his present crew, Hopkins had assembled a varied bunch. There was Quay, the cook/mammalogist, who, as Hopkins wrote his parents, “spends more time trapping, shooting and skinning animals and birds than he does cooking and taking care of camp, but that suits me fine and suits the rest of the fellows, too.” There was Art Fernald and Jim Seitz, both geology graduate students whom Hopkins thought well-trained and capable of working alone. And there was the fellow Hopkins was the most glad to have along, Bob Sigafoos, a big Dutchman from Ohio who was working on a Ph.D. in botany at Harvard. Hopkins had met him in an ecology seminar and found him to be a good talker as well as smart, witty, and thoroughly rebellious about received knowledge. On previous field trips, Hopkins had been collecting plants and trying to identify them on his own. Now he could work alongside a trained botanist. Most days, the two went off together. Each evening Sigafoos would take the lantern into his tent, using it to dry the day’s collected plants, then press them between sheets of clean newsprint bought from the Nome Nugget. The bridge game always waited on Sigafoos’ completion of that chore.

Rounding out the crew was Chuk (short for Inmachuk), a sled dog pup Hopkins had brought along, but who was not universally popular in camp. “The trouble started when a lot of our limited supply of fresh meat—I guess all of it—disappeared from where we had cached it within a day or two of setting up camp. We were reduced to fried Spam. And for a week or more, we would sit in our 8 × 10 cook tent, eating our fried Spam, door open, but mosquito net unfurled. Presently, we became aware of Chuk gnawing on a pork chop, right in front of the tent door. Later, as we’d be cleaning up the dishes, our little yellow dog would stagger into the tent, burping. Jim never forgave the pup, and the others never liked dogs anyway, so he was pretty much my dog thereafter.”

The crew’s official mission was to investigate a huge area —more than three hundred square miles—of lava flows in the Imuruk Lake region on behalf of the Engineer Intelligence Division of the U.S. Army. With the Cold War on, the Army was interested in locating sites for strategic airstrips in western Alaska. Army engineers thought the lava flows might provide a solid and permafrost-free substrate, but Hopkins saw the futility of the proposal with his first glance. Frost action during the cold stages of the Pleistocene epoch had fractured the gray-black basalt to form a rubble of angular blocks from a few feet in size to as much as twenty feet across. It didn’t seem possible even to run a bulldozer over it, let alone an airplane. Nevertheless, it was still a good chance to study the history of the landscape on the Army’s nickel. And Hopkins was eager to take an interdisciplinary approach in collaboration with Sigafoos.

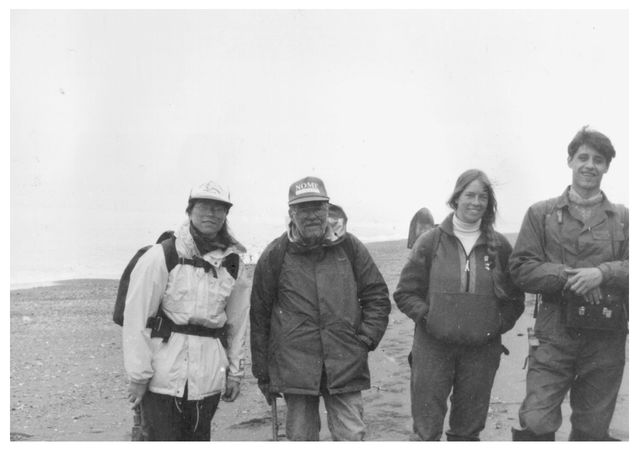

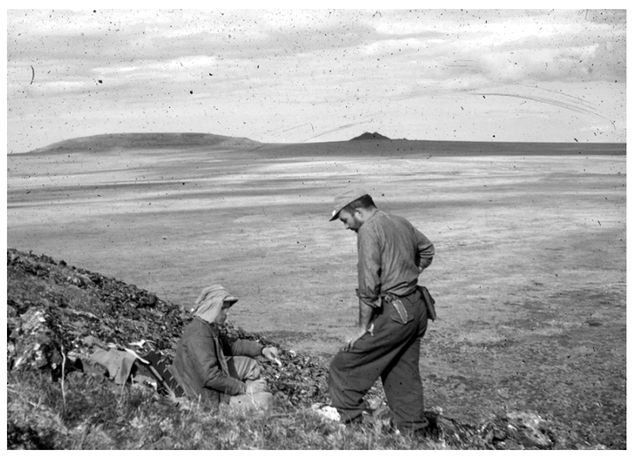

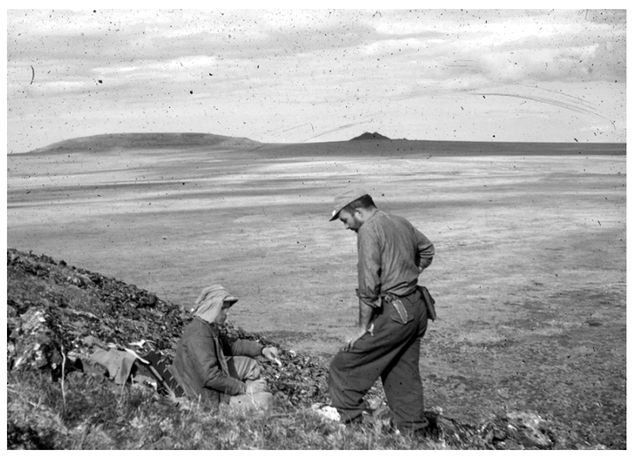

Wilbur (Bill) Quay and Bob Sigafoos on Skeleton Buttek, Seward Peninsula, 1948 (Photo by Dave Hopkins, courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

Bob Sigafoos idolized Eric Hultén, the Swedish botanist who was then working on a compilation of the flora of Alaska, Yukon Territory, Kamchatka Peninsula, and northeastern Siberia. It was being published in twelve long installments by the Lund University in Sweden, each volume straightening out the taxonomy of a whole family. That kind of writing was almost impossible for Hopkins to read, but Sigafoos lived from issue to issue, devouring the pioneering work of the great scientist. He immediately put Hultén’s articles to use as authoritative guides to identifying and classifying the tundra plants of northern Seward Peninsula. But Hopkins saw a bigger picture.

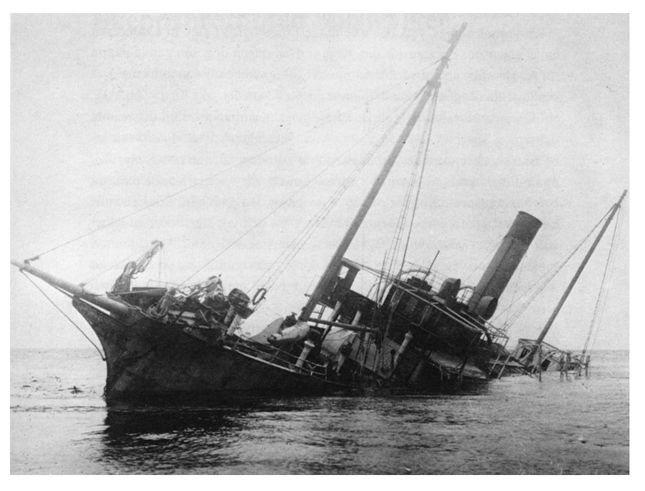

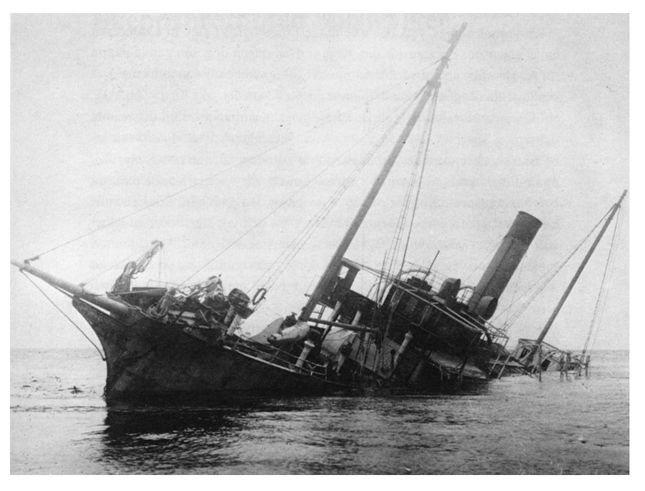

Hultén was a legend among Northern scientists, and Hopkins learned a bit about his life’s story from a long letter Hultén sent him years later. In 1920, at the age of twenty-five, Hultén had gone to unexplored southern Kamchatka in the Russian Far East as botanist to a small expedition. Though the trip doubled as a honeymoon for Hultén and his bride, Elsie, it turned out to be something less than a pleasure cruise. It took nearly three months’ travel—through Egypt, India, Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Yokohama—for the group to reach Hakodate, a port city on Japan’s northernmost island. They decided not to pay the steep fare asked by the first schooner heading to the Kamchatka Peninsula, and it was just as well. Within days, that ship, loaded with gunpowder and gasoline, exploded.

Hultén’s party did take passage on the next boat, the Kommandor Bering, which turned out to be the yacht of the former governor of Kamchatka. The governor, along with all officers and officials, had been recently executed during the ongoing Russian civil war, and the liberated yacht now carried the first Soviet governor of Kamchatka and other high officials. Unaccustomed to yachting, the Bolsheviks promptly piled the boat onto the rocks off the southern tip of Kamchatka. With the vessel listing sharply and taking on water, the crew managed to launch lifeboats, loaded with some provisions, and row everyone to the snowy beach. The next day, a storm broke up the yacht, and miscellaneous cargo washed ashore. The castaways had a camera but no film, guns but only bird shot. The area was so remote that there was no hope of reaching inhabited regions by foot. So the newlyweds set up a hut made from salvaged packing crates and, as the sanguine Hultén wrote elsewhere, “life in camp soon became quite bearable. We shot ducks and roasted them on spits, there was fish in the sea, the vodka flowed like water and all the signal rockets were used up in the merrymaking.”

The Kommandor Bering, carrying twenty-six-year-old Eric Hultén and his wife Elsie, wrecked off Cape Lopatka, at the southern tip of Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia, 1920 (Photo courtesy of Maj Hultén)

After about ten days, the shipwrecked party of Russians and Swedes sighted a Japanese steamer, which launched a boat. The captain refused help to anyone sailing on a Bolshevik-owned vessel, but he did agree to radio the Japanese fleet. After a few more days, two Japanese destroyers hove to in the heavy surf in front of the camp. Hultén’s Japanese letters of introduction earned the Swedes passage to Petropavlovsk, but again the Russian revolutionaries were denied help. Only after some parleying did Hultén secure permission for the Russian governor to come along so that he could arrange for the rescue of the remainder of his stranded comrades.

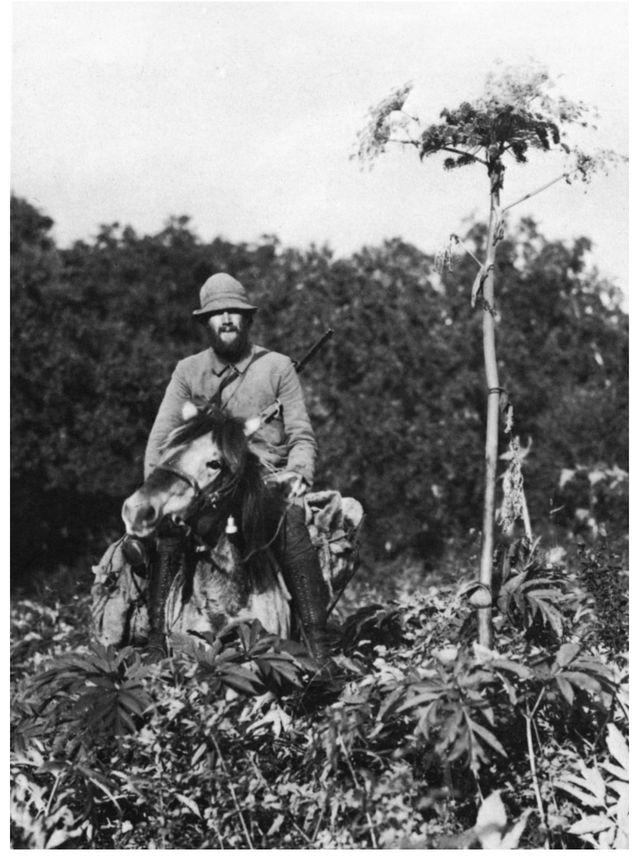

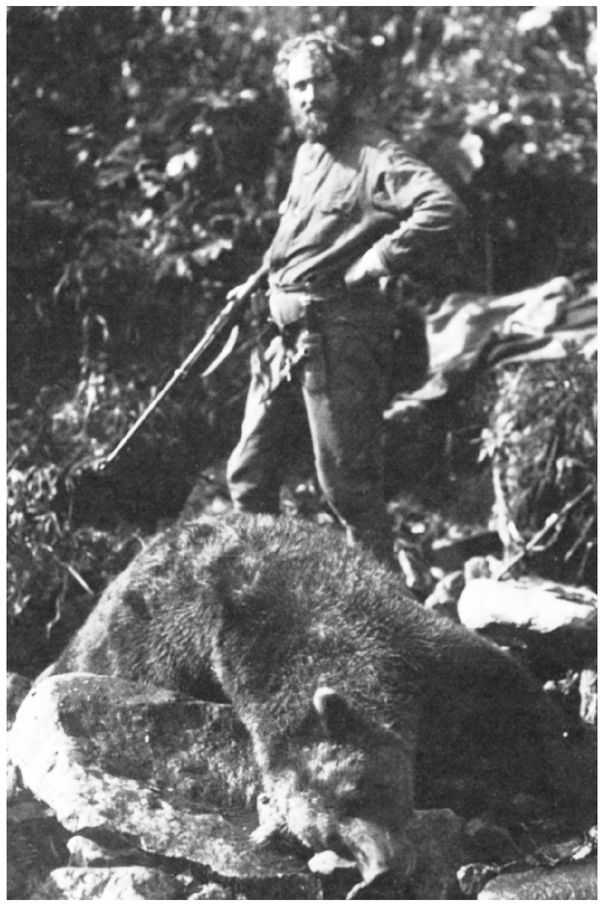

The intrepid Hulténs set up their base of operations in Petropavlovsk, ranging outward on botanical collecting trips into the rugged hinterlands, now more dangerous than usual because it was also a combat zone. Once, they climbed to the top of Avatcha Volcano while doing their best to dodge skirmishing factions in the civil war. Sometimes they left town with the Bolsheviks presiding over city hall, then returned to find the Czarists in control. On horseback, with two native guides, they took extended trips through virgin country of “radiantly beautiful . . . park-like birch woods.” Sometimes, they did not see anyone for months. Away from dangerous humans, they had only to contend with Kamchatkan brown bears lumbering through the underbrush. “Every week a bear was shot,” wrote Hultén, “and bear and salmon, salmon and bear was the food for the day.” Over the course of three years, they collected about twelve thousand plants, which set the Hulténs up with years of ambitious work in taxonomy and phytogeography (the study of the distribution of plants).

Between 1920 and 1922, Hultén and his wife conducted botanical field research in the wilderness of Kamchatka. They used horses in summer and skied in winter, with Hultén pulling a small sledge (Photo courtesy of Maj Hultén)

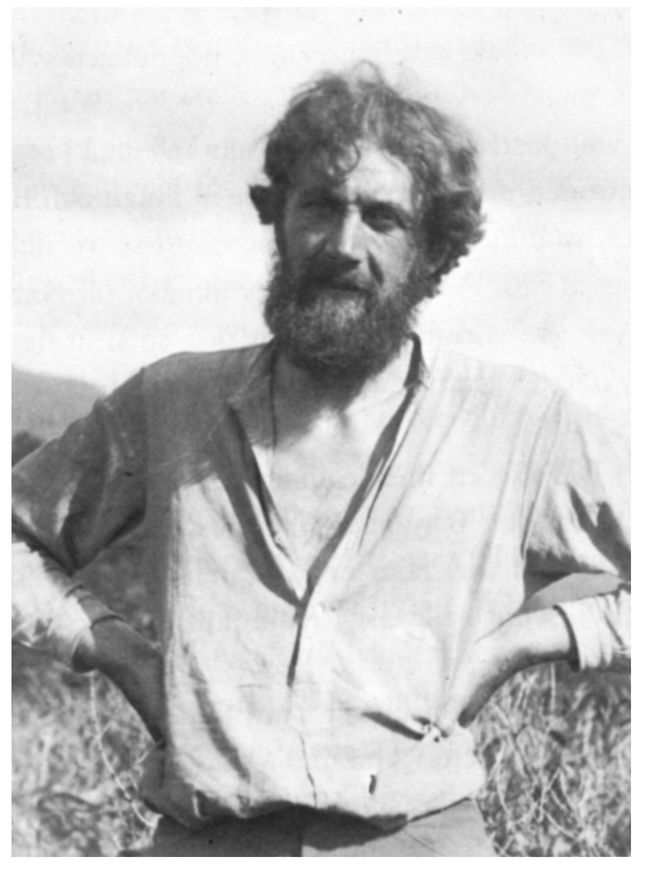

Hultén in Kamchatka: “Every week a bear was shot, and bear and salmon, salmon and bear was the food of the day” (Photo courtesy of Maj Hultén)

Luckily for budding Alaskan scientists like Hopkins and Sigafoos, Hultén’s interests led him to another wild land on the Bering Sea, Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. In the spring of 1932, at Unalaska, eight hundred miles west of Anchorage, he boarded a small fishing boat bound for Attu, the Aleutian island farthest west, another thousand miles distant. The captain of the Eunice allowed Hultén ashore whenever time and weather permitted. He climbed the steep volcanic mountainsides and collected “with great intensity,” he wrote, “while the boat was drifting off-shore, waiting.” Strong tides surged through the passes and straits, and there were no reliable navigational charts: “The only rule for navigation was not to sail into the kelp, the long algae covering the reefs.” The little Eunice returned from Attu safely, and Hultén went on to publish his Flora of the Aleutian Islands. But that the voyage was risky is attested to by the fate of the Eunice. On her very next trip to Attu, she wrecked. All hands made shore, where all died of exposure.

Hultén began to publish the results of these researches as part of his doctoral dissertation at the University of Lund in 1937. It described the distribution of vascular plants between Canada’s Mackenzie River and Siberia’s Lena. When he plotted the ranges of several plants on the same map, he saw they took the shape of ovals, elongated in an east-west direction. Interestingly, the ovals tended to be concentric. He noted, too, a peculiar symmetry in the plants’ ranges. The axis of symmetry was a line drawn through Bering Strait. “If they spread a little bit to the east of this line, they also spread a short way to the west of it. Should they spread far east, they also spread far west.” Hultén suggested they were grouped around “centra,” from which the plants must have radiated. And the central areas of radiation for various plants seemed to be not only in eastern Siberia and western Alaska, but also in the sea between.

When Hultén put this observation alongside what he knew of Ice Age conditions, a picture began to resolve itself in his mind. He knew that, when the ice sheets locked up much of the earth’s water, the sea level must have fallen enough to expose the shallow continental shelf under the Bering and Chukchi Seas. Hultén imagined a dry landmass stretching from mostly unglaciated Siberia into mostly unglaciated Alaska. Cut off from the rest of North America by ice sheets, such a region would have been a great biological refugium, a place where Northern plants and animals survived extinction, and whence they evidently spread when the glaciers receded.

Picturing the Bering Strait region during the Ice Age, Hultén imagined his plant communities extending in unified ranges from west to east across an intercontinental landmass. It would have been a broad highway of biological exchange, with floral and faunal traffic moving in both directions. Though hypothetical and drowned for ten thousand years, the land bridge should have a name, Hultén thought. He christened it Beringia, after Vitus Bering, a fellow Scandinavian and the first recorded explorer to sail through the strait separating Asia and America. Today, scholars consider Beringia to be not just the presently submerged land bridge, but the unglaciated adjacent lands extending westward to at least the Kolyma River in Siberia and eastward to the Mackenzie River in Canada.

Aware of Hultén’s Beringian hypothesis, Hopkins and his superiors at the U. S. Geological Survey thought a botanist might be a useful addition to his field party. Permafrost (permanently frozen ground) had just begun to be a subject of study for American soils engineers and geomorphologists, though there was already a substantial Russian literature. The Russians were showing relationships between vegetation types and such soil characteristics as permafrost or the depth of seasonal thaw. Besides, Hopkins’ superiors seemed to understand the value of simply dropping a good scientist into an area and giving him field support. He’ll get interested in something, and the result will be useful. And that was how Bob Sigafoos, a botanist, came to be sitting in the lee of the wall tent at Hopkins’ geological field camp at Lava Lake in the summer of 1948.

After nearly three years of fieldwork in Kamchatka, Hultén, then twenty-eight, returned to Sweden for years of study of the collected plants. At thirty-six, he published Flora of Kamchatka (Photo courtesy of Maj Hultén)

Sigafoos got interested in small-scale things, like studying the relation of vegetation to solifluction, how plants responded to frost-induced slope movement. This led to a paper, coauthored with Hopkins, that became a classic publication merging geology and botany: “Frost Action and Vegetation Patterns on Seward Peninsula.” Sigafoos also got interested in big things, like the history of the position of the tree line. He extended Hultén’s inquiries into the origin and history of the intricate mosaic of Arctic and subarctic plant cover. Like Hultén, Sigafoos was collecting plants, mapping their occurrence, and graphically overlaying the data to show the centers of Hultén’s equiformal areas, points from which plants had dispersed, hence the locations of refugia during the glaciations. Advancing the work of his hero, Sigafoos was using the living plants to reconstruct the vanished landscape of Beringia. And Hopkins was there, absorbing it all, reveling in the cross-pollination that profited both parties, just as he knew it would.

On July 15, 1948, Hopkins’ field crew moved enough of their gear from Lava Lake to establish a small satellite camp on another lake about twenty miles to the northeast, where the crew planned to map the geology. It was high up in the head-waters of Cottonwood Creek, which drained to the Goodhope River, which in turn flowed into the south shore of Kotzebue Sound. Hopkins named it Cloud Lake because, often as not, the lake was inside a cloud. “Every cloud within 50 miles passed over us,” he wrote home, “and every one of them dragged its bottom over the lake.” On days that were merely cloudy everywhere else, he said, Cloud Lake was lashed with wind and fog and drizzle. The wind never blew less than twenty miles per hour, and seldom less than thirty. The men wore wool underwear, wool shirts, wool sweaters, and rubberized rain parkas. Because the camp was on a sandy beach, when the wind wasn’t blowing rain, it was blowing sand. “I had sand in my sleeping bag,” he wrote, “sand in my shoes, sand in my hair, sand in all of the guns, sand in my coffee, sand in my hot-cakes, and sand in my soup.”

Kuzutrin Lake camp, 1948, showing Bob Sigafoos, eight-by-ten wall tents, and smaller sleeping tents (Photo by Dave Hopkins, courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

In the evening, all five men crowded into the eight-by-eight tent for dinner. For a bridge table, they spread a newspaper over a packboard. Seitz sat on a box of C-rations, Fernald on a gas can, and Hopkins and Sigafoos shared an air mattress. Sigafoos had an old reindeer skull for a backrest. Leaning back into it and fanning his cards, the curving antlers serving for his armrests, he must have looked like a Pleistocene chieftain consulting his magic. “It was a picture,” Hopkins wrote, “the five of us dirty and bearded—Bill sitting and cursing the stove or walking over the card table to go outdoors for food or water from the lake; Inmachuk poking his nose in the tent, trying to come in and add to the congestion.”

Hopkins went on to catalogue the artifacts of the crew’s material culture. On the floor were the stove, food, Quay’s sleeping bag and clothes, dead birds and lemming skins piled in with the food, pickled lemmings, owl pellets, and a can of dead snails. Against the amber canvas of the tent walls were a box of specimens, an ancient Eskimo wood implement, a rifle, two shotguns, and two fishing rods. In every other spot, wet clothes hung like bats, respiring steamy vapors, releasing an occasional dropping and imparting a dank redolence to the close space.

Camping at remote lakes on Seward Peninsula in the 1940s wasn’t always comfortable, but it was almost always interesting. For instance, there was the occasional visit from John Cross, the bush pilot who had been ferrying the crew and their gear from lake to lake with his odd looking, four-seat amphibious Seabee, powered by a single, rear-mounted pusher engine. Cross liked to drop from the sky and splash the bulbous fuselage down onto the lake in front of the camp and invite himself up to the cook tent for coffee and a chat. Hopkins was as enthralled with the bush pilot as he had been with Frank Gage of the Boston & Maine Railroad.

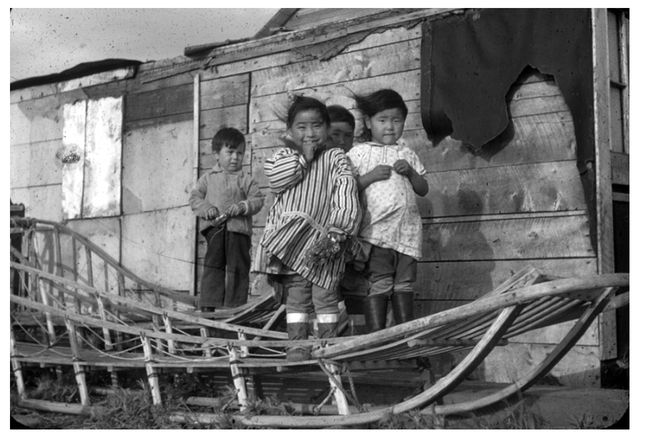

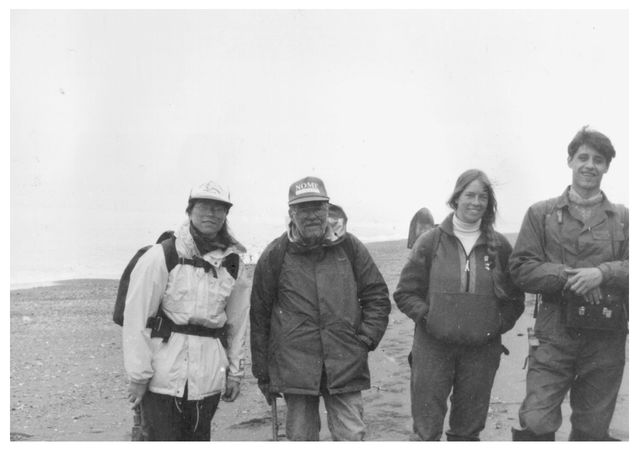

Eskimo children at Deering, 1948 (Photo by Dave Hopkins, courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

Cross was an independent operator based at Deering, where he lived with his wife, an Eskimo woman named Bessie Barr, and their three children. He had such a soft-spoken, serious, and understated manner that he seemed incapable of exaggeration. Hopkins thought of him as a sort of scholar without books. He paid attention to nature, then put things together for himself. And this knowledge—his interpretation of the natural world—he organized into stories. Still, his stories were so amazing that Hopkins could never be completely sure about them. One day when the party was camped at Imuruk Lake, Cross mentioned that if the scientists were studying Seward Peninsula’s prehistory, they might be interested to know that there were arrowheads in some caves over on Trail Creek, up near the lake the men were calling Cloud Lake. Hopkins definitely was interested.

It’s bear country, though, said Cross offhandedly. A fellow would want to bring along a rifle if he was going to go poking up those brushy ravines. A couple of miners from Candle were over there a few years ago. It turned stormy on them, so they figured they’d duck into one of those caves on Trail Creek. But they started thinking there might be bears in there. Well, these men were prospectors, said Cross, so they had dynamite with them. They threw a stick in there to scare the bear out. Sure enough, a grizzly came charging out, not one bit happy. Well, OK. They were ready for that. But as they were dealing with him, another bear charged out of the cave. They pretty much had their hands full with two grizzly bears, when they look up to see a third bear roaring down on them. But there were arrowheads in there all right. Bones, too. Sipping his coffee, the bush pilot gave his listeners to understand that, if they planned to go hiking up Trail Creek, they’d want to bring their rifles.

Bush pilot John Cross and his Seabee on Kuzitrin Lake, 1948 (Photo by Dave Hopkins, courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

Hopkins could not be certain whether Cross’s story—three bears in one cave, and the dynamite-tossing miners—was completely believable, but he got a glimpse of the caves once when Cross was able to fly him over Trail Creek. He was determined to explore the caves, and on the twenty-second of July, everyone but Sigafoos took off on a forty-mile spike trip that would take them down Cottonwood Creek to Trail Creek, up Trail Creek to the caves, then downstream to the mouth of Cottonwood Creek, and back by way of the Right Fork of the Goodhope River. It didn’t exactly rain the first day, though the willows conspired to collect the heavy mist, merging the atomized water and funneling it down to the point of each creased leaf. There it hung in fat droplets until it could be conveniently transferred to the clothing of the men pushing through.

Still, it was beautiful country. Cottonwood Creek flowed through a canyon with six-hundred-foot lava-topped cliffs on the south bank and rugged limestone ridges on the north side. As the men descended along game trails through steep-walled cut banks at the bottom of the canyon, each bend opened up new views. Here and there, the creek widened into a small flood plain where pleasant groves of fifteen-foot willows grew. The mists that hung on the cliffs above finally lifted, and the sun lit up a sparkling green valley. On the north wall, a family of eagles circled the eroded core of an ancient cinder cone as if tethered to it. That night, camping by the creek, Hopkins slid into his sleeping bag with wet long johns, hoping they would dry by morning. But he stayed awake until twelve-thirty, noting all these details in a letter addressed as usual to his parents, but with the knowledge that it would be shared with Mrs. Gage (the station agent’s wife), Lucy Brooks (the librarian), Nellie Mason (the post mistress), and paraphrased to the members of the Rotary Club who asked after him.

The men reached the mouth of Trail Creek the next day, just as a rain shower caught up with them. Through the boiling fog, they could just see the limestone cliffs. With great caution, Hopkins led the way. He circled high on the valley walls to avoid the thick brush, shotgun at the ready, a slug in the chamber. At the first cave, they sent the dog, Chuk, up to investigate. When nothing happened, they pulled the fireworks from their packs—not dynamite, but Fourth of July skyrockets and Roman candles purchased in Nome. With a burst of fire and smoke, the rocket roared into the cave, careening off the rocks inside and filling the interior with sparks, flashes, and a loud, echoing racket. Smoke poured out, but no bears. Finally, they lit their carbide lamps and crawled in. For the first thirty feet or so, the cave was between two and three feet high and six feet wide. Then it opened to a room about nine feet wide, twelve feet long, and high enough for them to sit upright. Beyond the room, the tunnel narrowed in both dimensions for another thirty feet before terminating at a solid wall of ice. They saw that wolves had used the room, as dung and chewed reindeer bones attested. They found the leg bone of a bear, a bone implement, and a sardine can.

At the second of the four large caves, the men were bolder. After having Chuk sniff the entrance, they lit their lamps and crawled in. They were more than a little optimistic about the cave’s archeological potential, half expecting to find early man artifacts sitting in plain view on the floor of the caves. Not only were these not evident, but the dirt was frozen immediately below the surface, eliminating the possibility of a test excavation. Hopkins left Quay to dig a small pit outside the entrance of the most interesting cave while he and the others climbed the rocks to check out some of the smaller holes. In their separate pursuits, each party verified aspects of John Cross’s stories. Hopkins’ gaze fell on a hump of overturned sod across the valley when suddenly it moved. He judged the grizzly to be a little smaller than a house.

Meanwhile, Quay unearthed a beautiful red-brown, jasper lance point. This artifact looked like what was at that time called a Yuma point, Hopkins thought, hence an example of one of the earliest cultures then known to exist in the New World. Back at the Cloud Lake camp, Hopkins laid the point out on a piece of cloth and photographed it. Then he packed it for shipment home. He decided that he would write up a short paper on the Trail Creek find. He’d send it to Louis Giddings, the Alaskan archeologist whom he had been dying to meet.

A week later, the crew packed up their Cloud Lake camp and flew back to the bosom of their nicely outfitted base camp at Lava Lake. Hopkins thought back on Cloud Lake as the prettiest place they had yet camped—and the most miserable. “I wasn’t warm once in the last two weeks,” he wrote home. But now they all took baths, trimmed their beards, and washed their dirty clothes. They had a table on which to eat and play bridge. When the sun broke through the clouds, they hung their damp clothes and sleeping bags out to dry, cleaned the guns, sharpened knives, and “rubbed the soot off the dirtier of the dishes.” Then the young scientists sat in the sun and caught up on their notes.

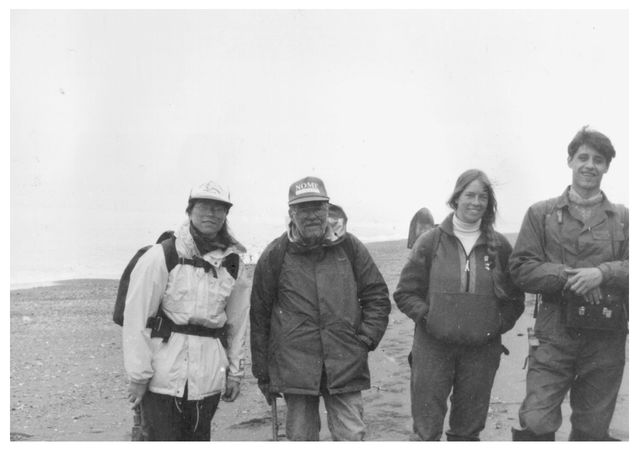

Sigafoos, Quay, and Hopkins dry gear and wait for an airplane at Lava Lake, 1948 (Courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

It was freezing at night, now, as August advanced. Instead of rain, wet snow pellets blew in on the wind. Restless birds began to aggregate. The sandpipers flocked up and left. High overhead, easier to hear than to see, a long, fluttering V of geese moved purposefully south. It was as if an invisible airplane had snagged the great strand in the middle and was towing it across the sky, advertising winter to the world below. The terns, the snipes, and the ducks disappeared. And now the cranes were flocking up at Lava Lake. In groups of a dozen or more they glided in, landing on the tundra on the north side. They stalked around, studies in rectitude, welcoming incoming brethren with deafening, unearthly, and earsplitting croaks, like the sound of a thousand pterodactyls strangling. As the flock grew larger, a handful of cranes began to jump and hop, inciting other birds until waves rippled through the crowd. When a hundred or more birds had gathered, the energy could not be contained. The center could not hold. The entire agglomeration rose, boiling and churning, like the early stages of a nuclear explosion. Scattered and inchoate at first, the cranes began to coalesce into small whirlwinds, which in turn merged and condensed as the birds wound themselves into a proper cyclone of biomass and commotion, rounding and wheeling and rising, auguring themselves into the sky until they were nearly invisible—like flecks of nutmeg swirled into a fluffy batter. When they seemed ready to disappear altogether into the white cumulus, the specks arranged themselves into perfect formation and, like a defiant compass arrow, shot away to the south.