6

SOMETHING GOING ON

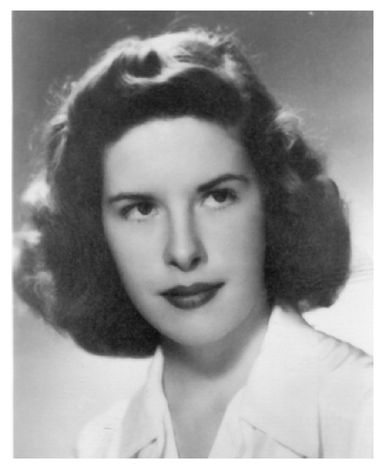

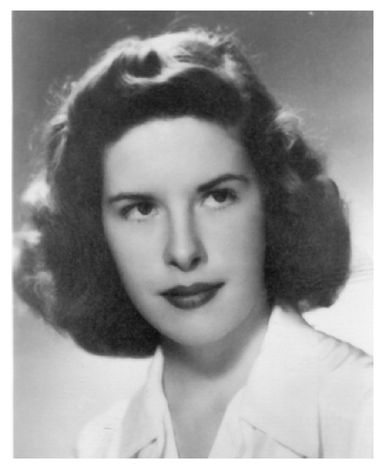

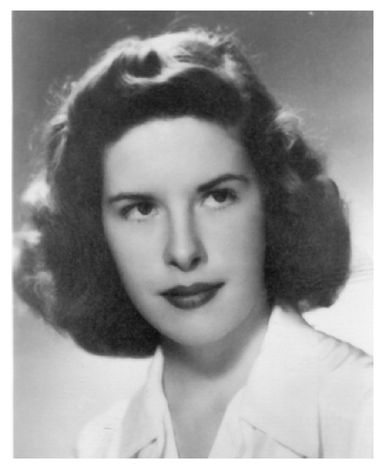

Joan (pronounced JO-ANN) Prewitt was a pretty, dark-haired twenty-year-old at Radcliffe College when she told Dave Hopkins, whom she’d been dating for some time, “There’s something going on between us.” Hopkins had sense enough to realize that the something was love and that he had been tendered “a sort of put up or shut up proposition,” as he says. They were married in New Mexico, where Joan had grown up on a ranch not only larger than Gypson’s Woods, but, Hopkins was amazed to learn, probably larger than all of Greenfield Township.

Joan had both a love of outdoor work and training in geology (she would earn a master’s degree from Radcliffe-Harvard). In the summer of 1950, she accompanied Dave on his field research trip to Alaska. They had the use of a surplus Army weasel, a light amphibious track vehicle powered by a six-cylinder Studebaker engine. On Joan’s twenty-first birthday they ran the weasel out to Cape Douglas, crossing the coastal plain and the old beach ridges. Hopkins shot a picture of Joan sitting on a giant boulder in front of the wave-cut limestone cliffs of an ancient beach, now high and dry. Once, when the tide was out, they took the weasel along the beach around the coast to the Eskimo village of Teller. For miles, there were only cliffs on one side and the sea on the other. They suddenly realized that if the weasel were to break down, they would die with the rising tide. The Studebaker engine chugged faithfully onward, however, and they made Teller, reminded of the Arctic’s capacity to claim the ultimate price for carelessness, and resolved never again to be so foolish.

Raised on a ranch in New Mexico, Joan Prewitt Hopkins earned a master’s degree in geology from Radcliffe-Harvard and assisted her husband for two summers in Alaska

(Courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

Joan worked with her husband for two summers in Alaska, returning with him to Washington, D.C., each fall, where Hopkins worked in the USGS’s Terrain and Permafrost Section. He felt two ways about living in Washington. He enjoyed the bookstores, especially the Washington Book Shop on Connecticut Avenue, where he attended parties and leftist lectures and heard Pete Seeger perform. He joined the United Federal Workers, which, he says, “was rather a left CIO union—and not just ‘rather.’” He was troubled by the racial discrimination he’d seen in the workplace and worked on grievances filed with the union. “In those days, black people only worked as elevator operators and messengers. Jews couldn’t be put in positions where they’d be working over non-Jews. So, promotions for almost anybody other than WASPS were very difficult.” Though these activities invigorated him, Hopkins found the D.C. winters dreary. Both he and Joan wanted to move west.

After the 1951−52 field season, Hopkins contrived to work for a month on an Alaska geologic mapping project at USGS’s Alaska Branch, then located in the old U.S. Mint building in downtown San Francisco. He and Joan, who now had a baby daughter, stayed with Clyde Wharhaftig in his apartment on Telegraph Hill overlooking the bay. Clyde had been Hopkins’ grad school roommate, a frequent guest in the family home in Greenfield, and best man at his wedding. Now the two best friends worked together. Every day they’d walk down Grant Avenue, through the Italian neighborhood of North Beach with its spaghetti factories and beatnik coffee houses and on through Chinatown, where the shopkeepers would be setting out vegetables on sidewalk stands. They turned up Market Street, crossing at the foot of Powell, where the clanging cable cars turned around on a big wooden turntable; and strode down Fifth to Mission Street, entering the USGS offices in the stately old U.S. Mint building. Colleagues in the Alaska Branch called Hopkins and Wharhaftig “The Gold Dust Twins,” because they had “gold-plated” diplomas (doctorates from Harvard), they had been to the gold fields of Alaska, and they were inseparable. When the temporary assignment ended, however, Hopkins returned to Washington and the Terrain and Permafrost Section.

The San Francisco−based Alaska Branch operated with considerable autonomy, almost like a miniature USGS, and that appealed to Hopkins. He applied for permanent assignment there, and, when the chance came in December 1954, he packed up his family and drove cross-country. It poured rain through central California, but as they reached the Dumbarton Bridge and crossed San Francisco Bay into Menlo Park, where the USGS had new offices, it poured sunshine. It was January 1, 1955, and everything was wet and sparkling. The air was fresh, the acacias were blooming, the birds singing—even the year was new. “It looked,” said Hopkins, “as though I had arrived in Paradise.”

The couple bought an old farmhouse in the Los Altos hills on five acres with apricot and plum trees, a walnut and a lemon tree. Joan reclaimed the gardens and trees and worked through a list of remodeling chores. She also did volunteer work for progressive political causes and candidates. Early in their marriage, she had gravitated toward her husband’s social and political philosophy, and, as Hopkins became more absorbed in his profession, “Joan became more and more my social conscience,” as he wrote a friend. It was more than that, he said, “she was my spark plug and steering wheel.” When she gave birth to a second daughter, Joan’s mother came to stay while Hopkins went off to the Seward Peninsula for another field season. It was during that time, while he was visiting various placer deposits around Nome, that a message from Joan’s mother finally caught up with him. It said simply: “Come home.”

When he reached a phone and called his mother-in-law, she would not, or perhaps could not, tell him what was the matter, but gave him the phone number of a doctor. Hopkins still remembers the first words he heard when the doctor got on the line: “Mr. Hopkins I’m awfully sorry we didn’t catch this in time.”

Cancer.

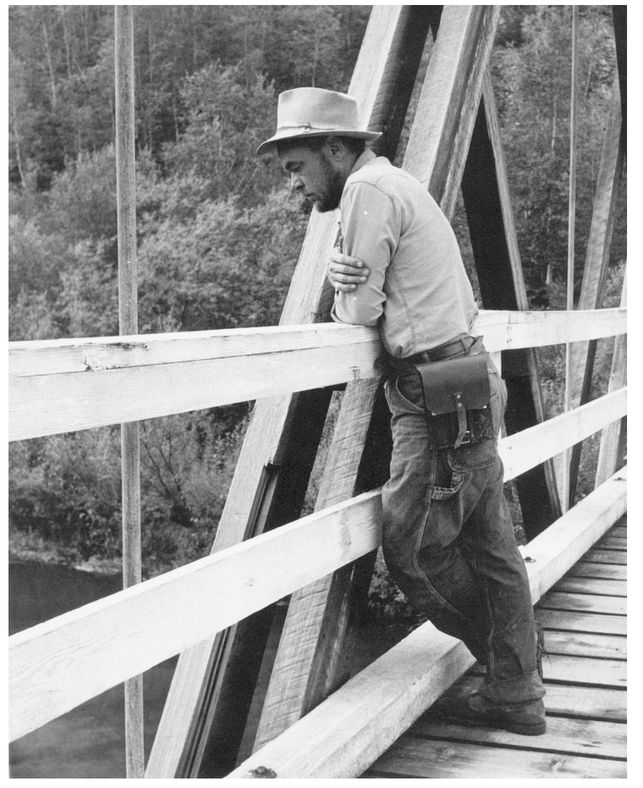

A grieving Hopkins at Manley Hot Springs in Interior Alaska in 1956 (Courtesy of Dave Hopkins)

More than forty years later, at the age of seventy-seven, Hopkins sat one day sifting through a box of photographs, happily annotating them with his memories. Opening one folder, he quickly closed it up and replaced it in the box. The pictures were of a young family in a sunny yard beside a farmhouse. His old eyes filled with tears, and he waited a few moments until he could get control of his voice. “That was when Joan was sick,” he whispered. “I can’t look at them now.”

Joan Prewitt Hopkins was twenty-seven.

While recovering from a disastrously incompatible second marriage, Hopkins attended the sort of encounter group common in the San Francisco area in the 1960s. There he met and eventually married Rachel Chouinard, a pretty, French Canadian woman with an easygoing nature and a lively sense of humor. Though Hopkins was in the field for months at a time each year, Rachel maintained not just a home for their combined family of six, but a group foster home that sometimes brought the total to eleven.