7

GIDDINGS

When the tide is out, there is just enough beach on the outer face of Cape Denbigh for a pilot who knows what he’s doing to land a light airplane. Moreover, when he sheds the weight of his passenger and cargo, he has a reasonable chance of taking off again. Art Johnson, a bush pilot operating out of the Eskimo village of Shaktoolik, knew what he was doing. As he dropped in from the north, his passenger, Hopkins, saw nothing but four-hundred-foot cliffs out the left window and nothing but breaking waves out the right. But Johnson had circled first. He had estimated the length of the beach at about a thousand feet and noted that it terminated abruptly in a steep cliff. He had gauged the size of the cobbles he would be landing on—about the size of softballs. And he’d checked the waves to figure that the wind was out of the south. Johnson dropped the plane in from the north, set it down safely, then turned and jounced back to the north end of the beach.

After Hopkins piled out with his gear, Johnson asked him to grab the plane’s tail and dig in his heels. When the engine whined and the prop wash blew hard in his face and the tail began to rise and tug, Hopkins let go. The little plane seemed to burst out of his hand like a released bird. He watched it run up the beach in a great roar and panic, the way a red-throated loon takes off, with its windmilling legs pattering wildly across the surface of the water until its flapping wings get a bite on the air. Once sufficiently aloft to clear a wing, the plane banked sharply across the face of the cliff, rose, banked again around the headland and was gone. Johnson had offered to pick him up at the same beach, but “after watching him take off,” Hopkins wrote in a letter, “I made darn sure that I got back to Shaktoolik by boat.”

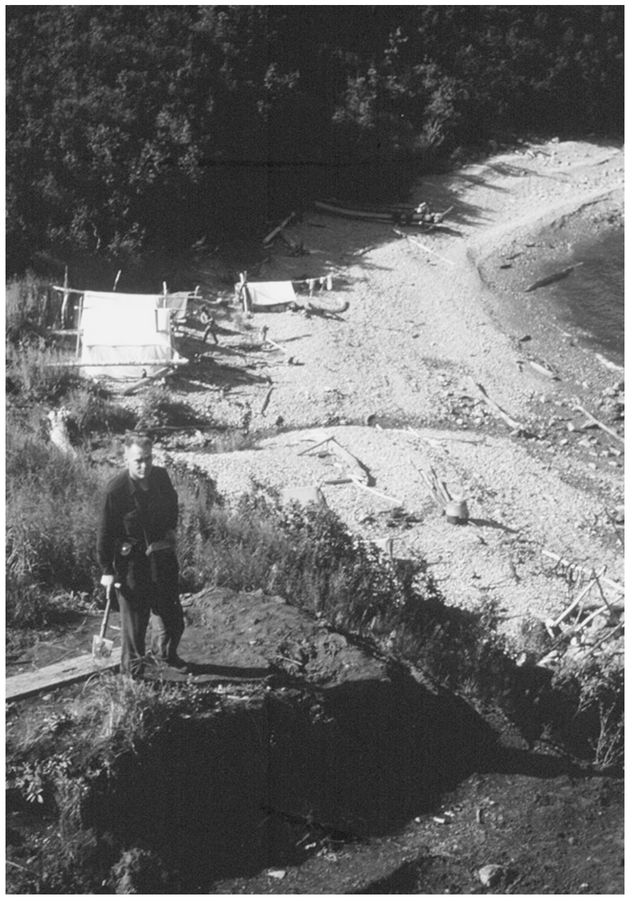

From the air, Hopkins had gotten a good look at the Reindeer Hills. It was a fist of high ground at the end of an arm of swampy lowland separating Norton Bay from its namesake sound. Cape Denbigh protruded southward from the fist like the thumb of a merciless emperor. On the seaward side of the fist, in what would be the indentation between the middle knuckles, is the place the local people call Iyatayet. Art Johnson had buzzed Louis Giddings’ camp at Iyatayet before setting Hopkins down on the beach a mile away. In bush Alaska, the low pass is equivalent to ringing the doorbell. Giddings dispatched his Eskimo helpers to pick up the visitor, and pretty soon Hopkins was skimming across the water in a boat sheathed with the skins of ooguruk (bearded seal). Rounding a cliff, he saw the little inlet where Iyatayet Creek tumbled out of the hills and slid across the beach into the sea. Beside the stream were four white canvas wall tents, and, on a grassy terrace forty feet above the left bank, he saw the fresh dirt that marked Giddings’ latest excavation.

Though his greatest discoveries were ahead of him, by 1950 Louis Giddings had already made a mark in Alaska. Hopkins, at least, had been hearing stories about the half-legendary Giddings for years. In Palmer in the early forties when Hopkins was mapping coal deposits in the Matanuska Valley, he used to run into a fellow named Jack Newcomb at The Lodge. Newcomb was in the Alaska Scouts, a military unit famous for its outdoor skills. He had worked occasionally as an archeological assistant, and would mesmerize listeners—especially Hopkins—with stories of the intrepid Louie Giddings.

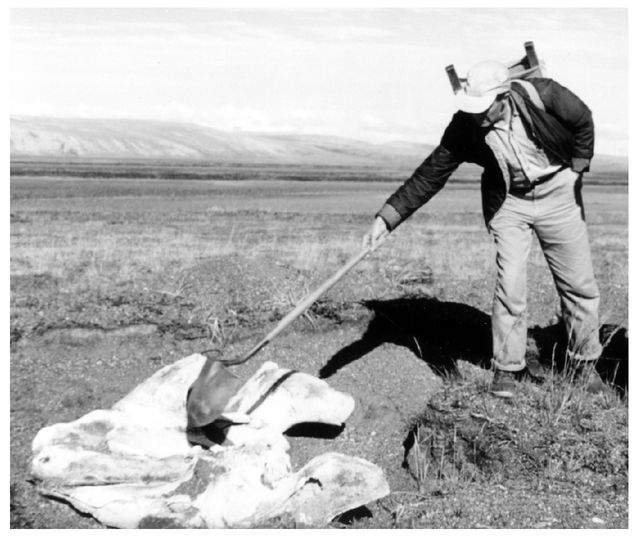

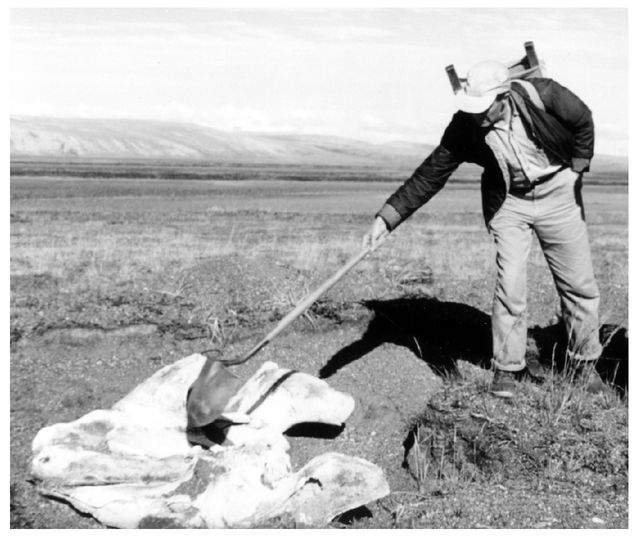

Hopkins at Louis Giddings’ excavation at Iyatayet Creek, Cape Denbigh (Courtesy of Haffenreffer Museum, Brown University)

Giddings was a tall, soft-spoken Texan who took epic trips across rugged country, sometimes prospecting for gold and sometimes for archeological remains. As one of Giddings’ professors wrote years later, “I remember him each spring going off into the wilderness alone, equipped with a bed roll, some small bags of rice and raisins and a .22 rifle to shoot the ground squirrels upon which he would live for months.” After graduating from the University of Alaska in 1931, Giddings spent five summers working for a mining outfit that washed away the overburden of silt with hydraulic “giants.” But another kind of buried treasure intrigued Giddings: ancient spruce wood that the hoses uncovered at various levels in the muck. Attempting to date the samples, Giddings worked out his own (ultimately impractical) method of tree ring analysis. Eventually, he wrote the inventor of dendrochronology, the astronomer Andrew Douglass, at the University of Arizona. Shortly, Douglass was sponsoring the promising student’s graduate study in Tucson.

While his master’s degree progressed, Giddings did fieldwork in Alaska and worked for the University of Alaska’s anthropology department. In 1939, he assisted Froelich Rainey and Helge Larsen in excavating the Ipiutak house pits at Point Hope, a find that had pushed Eskimo history back a thousand years. It was one of the great discoveries of the Arctic world, an unexpected prehistoric Eskimo culture notable for fantastic and intricate ivory carving and engraving. Hopkins remembers being just out of high school when National Geographic magazine ran a big spread on the spectacular find. “I was thrilled by it and began to think about meeting these mighty explorers some day.”

When Giddings thought about how the ancient people made a living at the end of a spit that jutted fifteen miles into the sea, he suspected they might have lived in the settlement only during the summer, where they hunted seals and walrus, then moved inland after freeze-up to hunt caribou. To test his theory and to work on a tree ring chronology, he wanted to look for sites along the Kobuk River that stretched inland from Kotzebue.

Giddings’ idea was to fly into the Athabascan Indian village of Allakaket on the Koyukuk River, a tributary of the Yukon, then hike west over a low pass to the Kobuk. On reaching the river, he planned to build a raft and float down toward the Chukchi Sea. He mentioned the plan to the University of Alaska’s longtime president, Charles Bunnell, who told him it was definitely unwise to attempt a trip of that length alone in totally uninhabited country. Giddings let the matter drop for a time, but he found he couldn’t shake the idea. He figured he could do it and thought a field party “needlessly costly,” even “encumbering.” He preferred to travel light, as he wrote in his classic memoir Ancient Men of the Arctic, “resting when I pleased, day or night, and accountable to no one.”

In July 1940, Giddings flew to Allakaket, which sits astride the Arctic Circle. From there, it is about ninety miles to the Kobuk River, with no trail markings and no settlements along the way. Fifty of those miles between the two rivers were simply uncharted, a blank space on Giddings’ USGS map. He took a light pack: a tent, a down sleeping bag, rain gear, and a change of heavy long johns (mainly for protection against mosquitoes). With respect to edible provisions, he was likewise unencumbered, depending on a .22 rifle, some fishing line, and flies.

At Allakaket, the horrified missionaries made it clear they opposed Giddings’ foolhardy plan. The last person to attempt the trip, they said, had never been heard from again. When Giddings waved good-by and headed up the Alatna River, the missionaries sent off an urgent letter to President Bunnell saying that, if Giddings didn’t return to Allakaket fairly soon, Bunnell should organize an air search.

The Alatna teemed with ducks, and along its shores Giddings ate well and enjoyed himself. When he judged he had gone far enough north, he adjusted his compass to follow a straight line west. From here to the Kobuk, he would have to rely on shooting squirrels and birds, and catching fish in the one sizable stream he would cross. Leaving the river, Giddings headed west into the soggy muskeg, stirring up swarms of mosquitoes.

The ordeal of the following three days made me keenly aware of the difficulties Indians had long faced in hot interior summers. For hours at a time no breath of air disturbed the cloud of mosquitoes that surrounded me. Although I wore my head net continuously, I nevertheless had to plug the air holes in my hat and anchor the net securely to the front of my shirt to prevent the buzzing, probing insects from finding every weak spot in my armor. If I sat to rest, so that the insulation of clothing tightened over shoulder or knee, some few of these small swordsmen unfailingly managed to thrust their weapons deep enough to draw blood. Walking hour after hour with or without the hot July sun, I perspired until my entire soggy costume grew saturated. ... Small gnats, “no see-ums,” and larger ones, “bulldogs,” found a way into, under, or through my head net, biting at leisure or flying blindly into my eyes.

Giddings hit the Kobuk exactly where he expected. Without ax or hatchet, he set about building a raft. He had intended to lash driftwood logs together with willow stems but found he could pin them together by using his tree borer as a drill, whittling pegs, and, like a Stone Age man, pounding them home with a rock. For three days, he floated down the Kobuk, periodically disturbing ducks and black bears from their fishing. He himself fished at the mouths of creeks and gorged on berries where he found them. Sixty miles downriver, he approached the fish camp of a Native family. When the people spotted him, they ran terrified into their tents and tied up the flaps behind them. The little raft had become so waterlogged that it was almost completely submerged. The white man seemed to come around the bend standing up in the middle of the river, no boat under him at all.

For the next three weeks, Giddings located and excavated archeological sites on the upper Kobuk, then bought a canvas-covered kayak from a Native man and worked his way another one hundred sixty miles downriver to the Eskimo village of Kiana, where he caught a boat to Kotzebue and a plane to Fairbanks. As word spread, professional archeologists marveled at Giddings’ accomplishment. Alone, and without institutional support, he had just completed a pioneering archeological survey of one of the most remote regions of Alaska.

After wartime service in the Navy, Giddings returned to study the Arctic woodland cultures. Over several years, he excavated seventy-three houses at twelve sites. In 1948, he was preparing to survey the shores of Norton Sound for sites that he might relate to Kobuk River cultures when a letter arrived from his former assistant, Jack Newcomb, the fellow Hopkins had met in The Lodge in Palmer. Newcomb now taught school in Shaktoolik on Norton Sound and was writing to tell Giddings of two nearby archeological sites he’d discovered. Giddings flew directly to Shaktoolik.

Looking over both sites, Giddings considered that surface leavings at each place indicated fairly recent occupation. His hunch was that the site the Eskimos called Nukleet, near the tip of Cape Denbigh, might be more promising than the place they called Iyatayet, ten miles away. He settled down and dug a test trench at Nukleet. But he was puzzled by the fact that at Nukleet nearly all the tools were of polished slate, while at Iyatayet flinty flakes were common on the surface of the ground. “Could there be,” Giddings wrote later, “at [Iyatayet], beneath a veneer of late occupation, the leavings of some people who, like those of Ipiutak, had preferred flints to slate?” As soon as the test trench at Nukleet was finished, Giddings moved camp to Iyatayet.

Working alone one day at Iyatayet, Giddings lifted the wooden floor of a sod house ruin probably occupied in the 1600s. Beneath it he found pottery shards, stone lamps, and chipped stone implements, some of which reminded him of Ipiutak artifacts considered to be two thousand or more years old. Below that level he found nothing but sandy silt. To be sure there were no more cultural layers, he continued painstakingly to trowel into the sterile, undisturbed soil. When it had become obvious that the excavation had reached its conclusion, Giddings, for some reason, poked the tip of his trowel into the soil to test the depth of thaw. Immediately, he felt the gritty resistance of flinty material. Using the trowel like a cake knife, he tipped out an intact slice of the compacted silt. Glittering underneath were countless tiny flakes of obsidian and chert and the glistening prismatic facets of microblades and projectile points. Giddings saw at once that they resembled the Middle Stone Age artifacts found in Europe. He was the first person to see anything like it in America.

There were large Yuma points similar to those found at Paleo-Indian sites in the American west. And there were hundreds of slivers of chalcedony, chert, and obsidian. These flakes had been chipped away to sharpen tools called burins, used for cutting or grooving antler and ivory. The delicate craftsmanship of the Denbigh people was especially evident in microblades. Barely more than an inch long but carefully flaked in parallel diagonal rows, they could be fit into slots grooved along the sides of weapon shafts. Giddings’ find at Iyatayet rewrote Eskimo archeology. Burins, for example, had not previously been found in America, and microblades were very rare. They were the most singular feature both of the Denbigh people’s tool kit and of ten-thousand-year-old cultures found in the Gobi Desert of Asia. Giddings believed that the Denbigh Flint complex, as he named the oldest layer of artifacts, was similarly ancient, though later work proved otherwise. Still, he had pushed back the antiquity of Eskimo culture to about five thousand years and established a connection between Old and New World cultures.

It was the jasper lance point that Hopkins had found at Trail Creek Caves that led to his first meeting with Louie Giddings and the invitation to visit Iyatayet. Hopkins had wrapped the point carefully for shipping to his office in the States. But in those days a package sent by air from Nome to a destination in the Lower Forty-eight might sit in Wien Airlines’ hangar in Fairbanks for weeks awaiting space on a southbound plane. Hopkins’ package was gathering dust when the building burned down. The jasper point was lost. Fortunately, he had sketched and photographed the artifact. On a trip through Fairbanks, with sketch and photo, maps and notes, Hopkins hiked one evening up to the log cabin on the University of Alaska campus where Louis Giddings and his wife, Bets, lived. The cabin, which still stands today, was built in the late 1930s by Giddings’ professor at the University of Alaska, Froelich Rainey. At that time, it was set well away from the other buildings, on a south-facing ridge with a view of the Tanana Flats all the way to the Alaska Range. Today it is flanked by dormitories, and the view is obscured by a stand of tall aspen trees that cover the slope.

Hopkins says he had been “just waiting for an adequate opportunity—an excuse, actually,” to meet Giddings. Decades later, he sat for an interview in the same log cabin on the University of Alaska campus, recalling the welcome he received there from Giddings and his wife: “What I remember was a very warm experience. The warm color of the logs which we can still see, the blazing fire in the fireplace, and also the warmth of Louis and Bets Giddings themselves.”

Giddings was a dozen years older than Hopkins. But, unlike Hopkins, who seemed always to be on the accelerated plan, always a couple years younger than his classmates, Giddings’ ascendancy was gradual. Like many University of Alaska students (then and now), he was older than the standard cohort and in possession of life experiences beyond schools. He was taking his time with his education, and never seemed completely sure if his preference was to pursue graduate studies or just to take off and go prospecting. He didn’t earn his master’s degree until nine years after graduating from college, and would not earn his doctorate for ten more years. But even if Hopkins at twenty-seven and Giddings at thirty-nine were at approximately the same stage of formal education, Giddings was already a notable figure in Arctic science. He had been visiting the Bering Strait region since 1934 and was the first person to apply dendrochronology to the Arctic. Finding that rings in Arctic trees were more sensitive to temperature than to precipitation, he worked out the first long-term record of ancient climate in the American Arctic. Applying this timeline to the wood found in ancient dwellings, he became the first person to precisely date prehistoric archeological sites in Alaska. Now he had just discovered the oldest known traces of Eskimo culture at Iyatayet.

Giddings was excited about Hopkins’ Trail Creek Caves discoveries. But he was also eager to get back to his own work at Iyatayet and couldn’t take on another project. He suggested that Hopkins send him a report of his test excavations at Trail Creek. Hopkins did so, and Giddings sent it on to his friend Helge Larsen in Denmark, offering him the chance to excavate what he recognized as the only known cave site in Alaska. Larsen was happy to do so.

As the field season of 1949 approached, Hopkins wrote Giddings that he “would like very much to visit you, if it can be done without inconveniencing you too much.” Giddings replied, “It would mean a lot to me to have you look over the site.” He hoped that a geologist could puzzle out the origin and age of the flint-bearing soils. But as things worked out, Hopkins’ own fieldwork prevented a visit to Iyatayet during the summer of 1949, though he did manage to visit Larsen at Trail Creek for a day in August. Larsen and his crew excavated the caves that summer and the next, collecting a wide variety of artifacts and bones. Near the surface were arrowheads of fairly recent cultures, extending back perhaps a thousand years. Beneath that were arrowheads and side blades similar to those found at Ipiutak. Lower still, they came upon obliquely flaked spear points like the one Hopkins’ party had excavated, apparently related to similar points from the American Southwest. At the deepest layer, Larsen found arrowheads and flints similar to the oldest artifacts Giddings was turning up at Iyatayet. He also unearthed antler projectile points cut with grooves on opposite sides, apparently to accept razor-sharp microblade insets, the only such find in Eastern Beringia. Larsen thought the artifacts might be eight thousand to ten thousand years old.

Now, a year later, as Hopkins jumped out of the skin boat at Iyatayet beach, Giddings was especially glad he’d come. He took Hopkins up to the excavation and explained the trouble he was having understanding the stratigraphy of the site, which should have been the key to dating it. As Giddings spoke in his Texas drawl, using his shovel as a pointer, Hopkins thought he was a wonder. He looked like a cowboy in archeologists’ clothes, speaking the archeologists’ language, the very embodiment of the outdoorsman/scholar he’d imagined since boyhood. The layer of Denbigh Flint culture artifacts, Giddings said, did not always lie parallel to the surface. Sometimes the flint layer bulged and curved like a wave. It showed up clearly in cross section, traced on the pit walls that were parallel to the slope of the hill. Here, the ancient layer of flints sometimes folded over itself, like an S, even though the soil layers above it might lie more or less parallel to the surface. What was going on?

Hopkins jumped down in the trench and probed in the dirt. It didn’t take long for him to recognize the geologic processes involved and explain it to Giddings. He and Bob Sigafoos had been studying the phenomenon on Seward Peninsula. Nevertheless, he was amazed to find that Giddings, used to working on a much finer scale, had prepared terrifically detailed drawings of the folds. Hopkins explained the process called solifluction. In the spring, on a slope underlain with permafrost, the upper layers of soil can thaw and become saturated with surface melt. Where saturation, steepness, and soil conditions favor it, this material can creep downslope as a lobe. The layer bearing the cultural material may be thawed in some upslope places, but frozen downslope. Thawed sections can slide downhill and override still frozen and immobile lower sections, producing the S-shaped strand. It is something like a miniature underground landslide, soil folding over itself underneath the surface, sometimes visible on the surface as an uphill slump and a downhill bulge. Surface deposits over time may add to the soil depth, burying the S-shaped layer deep underground. That was how Giddings found the Denbigh layer at Iyatayet.

As Hopkins and Giddings began to synthesize the archeological and geological evidence at the site, they found they could infer ancient fluctuations in climate and sea level, and speculate as to the age of the oldest artifacts. The paper they coauthored on the topic was one of the earliest attempts to relate archeological sequences to geologic and climactic chronologies. As it happened, their best guess was off by a few thousand years. But the advantages of interdisciplinary collaboration were not only reinforced in Hopkins’ mind but also demonstrated to the scientific world. From then on the two great Arctic scientists became friends, correspondents, and consultants to each other.

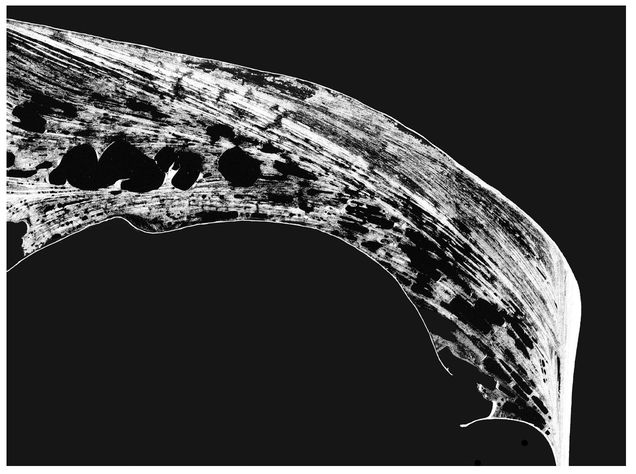

Giddings, too, moved between disciplines. His first scientific specialization, dendrochronology, is a technique that begins where counting tree rings leaves off. Besides the number of annual growth rings, the size of the rings offers information. Favorable weather conditions produce more growth, hence wider rings. When conditions are less favorable, growth is retarded, and the rings are comparatively thinner. So, a given tree will have a sequence of rings of varying thicknesses. When a tree is cored, the ring pattern can be read—like a bar code—to identify the particular sequence of years during which the tree lived. Trees of the same age, from the same region, would have similar sequences of wide and narrow rings. But even trees of widely different ages can be aligned if their lifespans overlap. One simply matches up the portions of the cores where the sequence is the same. The first fifty years of a living three hundred-year-old tree, for example, may overlap with the last fifty years of a tree that lived for five hundred years, then was toppled and became a house post. By aligning the rings that match, a continuous sequence can be obtained for the last seven hundred fifty years (three hundred plus five hundred years, less fifty because of the overlap). When the rings of an even older piece of wood can be matched with those of the house post, the record is extended back farther.

Stylized tree ring cores depicting cross-dating of living trees and wooden remains (Courtesy of the Laboratory of Tree Ring Research, University of Arizona)

Like pasting together a mosaic of overlapping photographs shot in a panoramic sequence, a tree ring pattern can be extended backward indefinitely. Ancient ridgepoles, rafters, tool handles, and charred bits of firewood can be cored and matched. Working from the living trees and wood from old Eskimo village sites on the Kobuk River, Giddings established a tree ring chronology for the last one thousand years.

Perhaps it was Giddings’ habit of seeing in ripples the passage of time that worked on his mind as he looked down from small airplanes onto arrays of old beaches around Bering Strait during the 1950s. At Choris Peninsula on Kotzebue Sound, he saw old beach ridges parallel to the shore and extending inland in ranks. Between the ridges ran swales, sometimes collecting so much water that they looked like canals. Digging on one of these beach ridges, he discovered huge oval house pits—up to thirty-nine feet in length—that contained some of the earliest pottery found along that coast.

A prograding, or advancing, beach like the one at Choris grows as sand is washed from an eroding beach and transported along the shore by the currents. Eventually, a large storm or high spring tides with strong onshore winds will drive the surplus sand and gravel to shore and heap the material into a ridge just below the temporarily elevated sea level. When the sea falls again after the storm, a new ridge stands above the shoreline, like a new ring added to the outside of a tree. Giddings identified nine beach ridges at Choris Peninsula. Since the oldest ridges lay farthest inland and the newest at the present shoreline, their position indicated relational age.

At Cape Krusenstern (shown here) Giddings found over one-hundred beach ridges containing the leavings of progressively older cultures (Photo from Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska. Retouched for clarity.)

Further, Giddings noticed that the ages of the house pits he excavated at Choris corresponded to the ages of the ridges on which they were found. While nothing prevented a relatively younger culture from building their houses on an older beach ridge, farther from the sea, Giddings reasoned that people who hunted sea animals would find it handiest to camp close to the shore, near their boats. Hence, as one progressed inland from the sea, the ridges encountered were likely to contain the leavings of progressively more ancient people. Beach ridges, Giddings thought, could provide a kind of horizontal stratigraphy, a new way to chart the sequence of the prehistoric cultures of Bering Strait. As he set about to find more places where beach ridges were piled up, he turned to Hopkins.

Hopkins had long been interested in ancient shorelines, and he had a good collection of aerial photos that covered all of Seward Peninsula and other places around Kotzebue Sound. He recommended that Giddings look in three places.

I suggested Cape Espenberg, where there is a very conspicuous set of beach ridges ten or fifteen kilometers long. ... [Another was] just north of Cape Prince of Wales, where the coast swings out and a broad cluster of beach ridges confine [Lopp Lagoon]. And the third place, which had a very large sequence of beach ridges, was Cape Krusenstern. So, I suggested those places to go. During the next summer, he went to all of them. Cape Espenberg was disappointing because it was very sandy, consequently well vegetated and in part covered with large dunes and not much to see. Wales turned out to have some elevated beach ridges, and he found Denbigh material on the innermost ridge. And then everyone knows about Cape Krusenstern.

What Giddings found at Cape Krusenstern, which lies at the north entrance to Kotzebue Sound, was 114 beach ridges parallel to the shoreline and extending inland three miles from the sea. They contained a sweeping record of human habitation, older and more continuous than any beaches previously found. Every known cultural stage of prehistoric Eskimos in northern Alaska could be plotted on this remarkable full-scale graph, and there were at least two more that had not yet been recognized. Giddings’ beach ridge archeology had proved a brilliant notion, and, with Hopkins’ help, he continued to explore the Alaska coast looking for fossil beaches.

Hopkins followed these investigations with great interest, mainly because archeology thrilled him. He simply wanted to be a part of the exciting discoveries, like the one at Cape Denbigh, that illuminated deeper and deeper recesses in the history of human presence in the New World. But he also saw that archeology could help geologists. Giddings’ dating of cultural remains permitted Hopkins to date the beach ridges within a few hundred years, to conclude that sea level then was just becoming stabilized at roughly its present level, and to begin to estimate the frequency of great storms and the rates at which the coastline had changed due to erosion and deposition.

He realized that beach ridge archeology could help geologists’ attempt to verify minor sea level fluctuations thought to have occurred in the past five thousand to six thousand years, when glaciers were known to have expanded. These fluctuations had been difficult to demonstrate because sea level was frequently measured against the land’s height in places where the land was subsiding. Obviously, no beach ridge dweller would dig his house into the water table. So, if house floors on a given beach at Cape Krusenstern were a foot under water (below the level of the lagoon and the sea), then either the sea level had risen, flooding the house, or the beach ridge had sunk, submerging the floor. Subsidence could be caused by regional warping or stretching of the earth’s crust, or by melting of the underlying permafrost. So, if localized subsidence was the cause of a drowned house pit, it would not help date sea levels. But if a corresponding beach ridge (as identified by cultural material) at a distant place, like Cape Prince of Wales, showed the same inundation, then it more likely would be attributable to a general, worldwide change in sea level, rather than a local change due to subsidence. And an accurate history of sea level fluctuation, Hopkins figured, was the same thing as a history of the emergence and submergence of the Bering Land Bridge.

“The things that you have learned during the past summer,” Hopkins wrote Giddings, “contribute tremendously to an understanding of sea level history and storm regimes. ... They hold great promise of contributing to our understanding of the precise genesis of the ridges themselves.” And they set Hopkins thinking about new things: “Until I received your letter yesterday, it had never occurred to me to apply the new understanding of sea level history to an attempt to date the beginning of beach formation in western Alaska.” As for Giddings, the correspondence between the two friends shows that he relied on Hopkins to suggest locations to investigate, to provide maps and aerial photos, to analyze the geology of the productive sites, to propose field strategies (such as the collection of mollusk shells), to sketch a picture of the environment thousands of years ago, to help with dating, to recommend him for funding at various agencies, and to comment generally on his emerging ideas.

Hopkins, who could not resist following his curiosity (sometimes to the exclusion of his geological research), was delighted to be involved in Giddings’ discoveries. During the summer of 1959, he took time from his own fieldwork on Seward Peninsula to visit Giddings at his camp at Cape Krusenstern.

On a guided tour of the several prospects there, Hopkins, then thirty-seven years old, got a taste of what it was like to keep up with a fifty-year-old Louis Giddings when he donned his old fashioned Trapper Nelson wood and canvas packboard, pulled his ball cap down on his head, and struck out across the tundra.

The first time I visited, we covered the whole of Cape Krusenstern. Cape Krusenstern is very, very large. The beach ridge complex itself is probably about three miles wide and tens of miles long. So we hiked a complete transect across the beach ridges near his camp. ... Then we got into an outboard and went to the inner [landward] edge of the lagoon because Louis knew where there were some shells weathering out. ... Then he wanted to take me up to see the Palisades site. So we climbed the hillside to see Palisades I and II. Then we came down, and then we hiked over to some early Thule houses, which had been burned with the occupants in them. Perhaps we didn’t do all this in one day. What I recall is that we walked very, very, very many miles. Louis had long legs and we were walking side by side, but I was exerting myself. Finally, after many hours, I said, would you mind if we slowed down a bit? He said, Oh, yeah. I would have liked to have slowed down long ago. I was just trying to keep up with you.

Giddings’ take on the event is supported by the recollection of Paul Dayton, Giddings’ nephew and field assistant, now a professor of marine ecology at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California: “Hopkins came by Krusenstern just briefly when I was there and all I can remember is that he walked faster than hell! We went a long ways (several miles) each day and I had to run to keep up with him.”

The horizontal stratigraphy that Louis Giddings developed at Cape Krusenstern was recognized for the spectacular discovery that it was. But some archeologists questioned his conclusion that the farthest inland sites at Krusenstern, which he called Palisades II, were two thousand years older than sites on a beach ridge he called Beach 53. These were the new cultures Giddings had found, and they both contained similar and distinctive side-notched points. Since it was possible for the Beach 53 people to have also built houses farther inland at the Palisades, the question arose as to whether Giddings’ dating was wrong—that really only two phases of one culture were represented. What he needed was the incontrovertible evidence of a good vertical stratigraphy that matched the beach sequence. And rattling around in the back of Louis Giddings’ mind was a clue as to where to dig for it.

A characteristic shot of J. Louis Giddings, in his wood frame Trapper Nelson backpack, using a shovel as a pointer, declaiming on a bowhead whale skull, Cape Krusenstern, 1961 (Photo by Dave Hopkins, courtesy of Dave Hopkins)

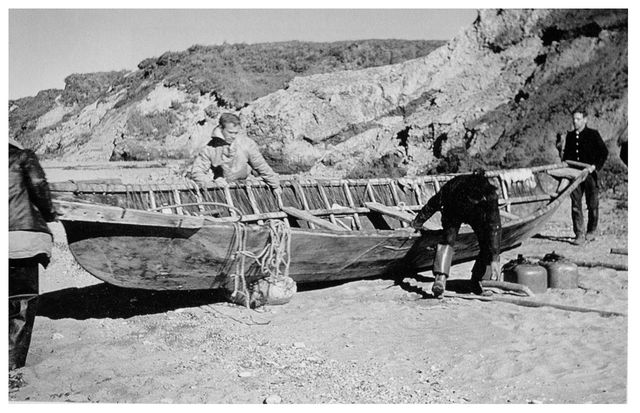

Hopkins (right) and crew launch a skin boat by rolling it over an inflated seal skin, Baldwin Peninsula, 1961. Others, left to right: Dan Libsourne of Point Hope; Dick Janda, geologist; Willy Goodwin, Jr. of Kotzebue (Photo courtesy of Dave Hopkins)

He had seen the place twenty years earlier. In 1941, the summer after his epic solo raft and kayak trip, Giddings had returned to the Kobuk River to excavate some of the house pits he’d discovered in the earlier survey. At a place called Onion Portage (for the wild onions that grew there), Giddings dug four house pits. In House 1 he found a microblade and micro-cores from which microblades had been struck. The only similar artifacts ever found in Alaska to that point came from the Campus site at Fairbanks, which was thought to be a very old site. The microliths seemed out of place in the fifteenth-century Onion Portage house. For twenty years, the little flints nagged at Giddings like so many stones in his boot.

Was it possible that there were more layers of artifacts beneath the floor of House 1? Could a house builder in the thirteenth century have dug into an older house depression and so heaved up to the surface some more deeply buried materials? Could this have even happened more than once, with the flints climbing up the stratigraphic rungs with each new excavation? In the summer of 1961, Giddings decided to return to the Kobuk and investigate House 1 again in the hope of verifying Cape Krusenstern’s horizontal stratigraphy.

In early July, he left his crews digging at Krusenstern and flew alone to the Kobuk. He landed above Onion Portage, unfolded a rubber kayak, and set off down the river. On July 5, he reached the familiar grassy bank, profuse with wild onions and shaded with poplars beneath a birch-covered ridge. It sat on a long, narrow peninsula around which the river coursed in a wide bend. In earlier days, when the men lined their boats up the river, the women and children could cut across the portage at the base of the peninsula, shortening their trek and picking wild onions as they went. The site had been perennially occupied, because migrating caribou habitually crossed the river here in the fall. Once out in the river, the swimming caribou could be killed easily with spears from one-man bark canoes. As an additional attraction, there was a nearby source of jade, which the hunters could work into tools while they sat in camp waiting for the caribou.

Giddings found the ground thawed about a foot deep and commenced a test excavation in one of the house pits that he had excavated twenty years earlier. “For a moment I had misgivings,” he wrote later, “I remembered how well we had cleaned the floor and the deeper tunnel in front and how little reason we had then to expect anything more in the frozen ground below.” Nevertheless, his shovel hadn’t penetrated the length of its blade before he felt it contact a scratchy material that was not gravel. He found cracked bones and charcoal at first, then, troweling carefully, uncovered “a tantalizing group of artifacts.” There were obsidian end scrapers, skinning knives, bifaces, and some sort of drill-like objects. Certain that a more complete excavation was justified, Giddings paddled down the river to Krusenstern to rejoin his crew. When the work there was finished, he and his assistants piled into small boats and motored back up the Kobuk River to excavate Onion Portage.

What Giddings and his crew found under the house at Onion Portage could not have been imagined. He had no sooner removed the layer of sod in three test cuts when he found in each “roughly matching one another and paralleling the surface of the ground, streaks of black, gray, and yellow earth.” Digging further in one spot, he found “that there was no limit to the neatly stacked layering of old surfaces.” The cultures he had found on the beach ridges at Cape Krusenstern were recognizable here, in the same sequence, but now stacked vertically, proving their relational age. He found both Denbigh materials and the same side-notched points that he had discovered at his Palisades II site. But the Palisades II artifacts were five feet deeper in the ground than the Denbigh materials, proving his assertion of Palisades’ greater antiquity. The site was not only the finest example of distinct stratigraphy ever discovered in America, but it contained more than thirty culture layers extending back eighty-five hundred years.

It took a few years of roaming around Seward Peninsula for the idea to take shape in Hopkins’ mind. He had a good friend in Bob Sigafoos who, following Eric Hultén, was interested in reconstructing the ancient landscape on the basis of the living plants. His new friend Louis Giddings was the person who knew the most about the history of ancient humans near Bering Strait. And he himself was becoming increasingly interested in applying geology to date old beaches, old glaciers, changes in sea level, and so on.

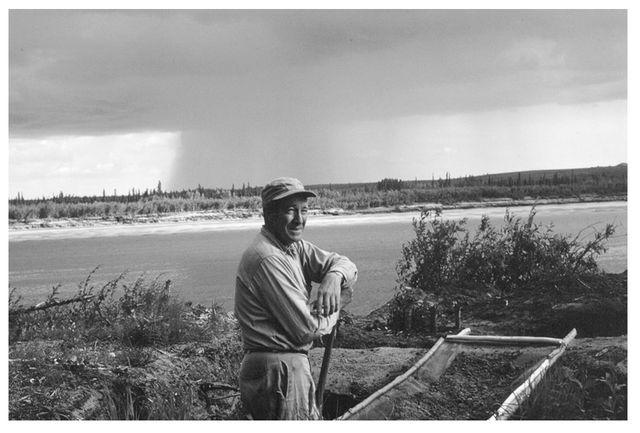

Louis Giddings excavating at Onion Portage on the Kobuk River in 1964. A few months before his untimely death (Courtesy of Haffeneffer Museum, Brown University)

And it suddenly occurred to me that if we three got together we could perhaps solve—now put quotes around that—we could “solve” the problem of the Bering Land Bridge. We could show whether it existed or not, and when it existed or not.

It was a problem everyone was interested in, remembers Hopkins. “The land bridge was in the air. It had been for years.”