9

WRITING THE BIBLE

At about this time in his efforts to nudge insular and turf-bound scientists toward communicating with one another, Hopkins got a major break. He had been, as he says, “making enough noise” about the Bering Land Bridge that John Lance, representing the International Association for Quaternary Research, visited him at his office in Menlo Park. He invited Hopkins to organize an all-day symposium on the land bridge for the INQUA conference, to be held in 1965, a year and a half hence, in Boulder, Colorado. Naturally, Hopkins was delighted. Delighted “to be noticed,” first of all, and delighted “to do something prestigious.” Very soon, he says, “It occurred to me that this was a way to get some of these people to talk to each other—or, at least, embarrass themselves by having their disagreements in an open forum.”

Because INQUA was both international and interdisciplinary, the land bridge symposium would be the premier event for a great range of interested scholars. Anyone he might approach would be pleased to accept the invitation to prepare a paper—and that certainly was not the usual case. The papers of two dozen top people, presenting new work on a single theme, held the promise of becoming an important book. Hopkins leapt at the opportunity and sent out a call for papers. When he had finished securing commitments, he had papers in the fields of geology, molluskan paleontology, vertebrate paleontology, micropaleontology, geophysics, paleomagnetics, oceanography, geochronology, botany, cytology, paleobotany, palynology (pollen studies), physical anthropology, and archeology to be given by scientists from the United States, Canada, the Soviet Union, Germany, Great Britain, and Iceland.

Hopkins was determined not to allow factions to present their views in apparent ignorance of other differing opinions and methodologies, as his friends Don Savage and Wyatt Durham had done earlier. He wanted the meetings to be a true dialogue. To set things on that course, he first asked for lengthy abstracts from the writers. Then he sent the abstracts around to the other contributors in advance of the conference. As a result, when the people arrived at the conference in September, they were ready to exchange and debate ideas, and the conference was praised for its focused discourse and as a model for scientific symposia generally.

Crowding his luck, Hopkins used his editorial role after the conference to continue to press each contributor to deal in print with his colleagues’ findings, whether those findings were complementary or paradoxical. At first, several papers arrived that “sounded as though [their authors] hadn’t been present at the symposium,” he says. Apparently, in that Colorado range-land locale, the scientists seldom had heard a discouraging word. Hopkins would not play along. He would simply phone them up and say, as he did to Wyatt Durham, for example, “OK you say this happened at such a time, and Repenning is saying that something else happened that required dry land at exactly that same time. And I don’t want to insist that you change your mind, but I want you to acknowledge what Repenning says and explain why you differ. And I said the same thing to Repenning. And the same went on through the whole volume.”

Though it was 1965 and relations with the Soviet Union were not cordial, Hopkins longed to exchange ideas with his Russian colleagues and to bring them into the community of international scientists working on the land bridge problem. He imagined the Russians as mirror-image workers, studying in a mirror-image landscape, unnecessarily separated by a political barrier. By inviting half a dozen Russian researchers to contribute papers to his book, Hopkins was building his own bridge across Bering Strait, an intellectual one that would lead to the first reciprocal scientific exchanges between Russian and American geologists and paleontologists. But it also made for a lot of extra work. He had asked the Soviet scientists to submit their papers in both Russian and English. The latter arrived in “terrible shape,” he said. The scientists had little English and their institute translator had little geology. Hopkins had never had a course in Russian, but he taught himself to transliterate with the help of a dictionary. He fixed sentence-level problems in this way, but some papers needed a complete rewrite. To do that, Hopkins recruited a Russian-speaking friend to read the paper aloud while he, himself, typed, making editorial changes as he went along. “I edited all the Russians heavily,” he said, “so they didn’t read like Russians writing in English anymore.” When Hopkins first visited Russia two years after the book was published, he was worried about the authors’ reactions. “I always expect that when I meddle with people’s writing that much they will be very angry with me. Instead, the Russians were extremely pleased because I’d made their work available to the outside.”

Next, Hopkins lined up a publisher, Stanford University Press in Palo Alto, practically next door to the USGS’s Menlo Park offices. All of this effort took time, of course, and Hopkins did have other work to do at the Geological Survey. He explained to his superiors that he was organizing this symposium, that he wanted to produce a book from it, and that during the next two years he expected to be working about half time on the book. Don Eberlein, then chief of the Alaska Branch at Menlo Park, thought that was all right and sent the proposal on to Washington for approval. Eventually, a letter came back saying, essentially, “Sounds like Dave intends to go to work for Stanford Press for a couple years. It seems as though perhaps he’d better bow out of this as gracefully as he can.” Hopkins was aghast. He talked it over with Eberlein, who said, “Well, you know, just do it.” Some years after Hopkins just did it, one of the Survey’s Washington big shots managed to get Vice President Hubert Humphrey to tour the Menlo Park offices. On that occasion, Hopkins’ superiors ceremoniously presented the vice president a copy of the freshly printed The Bering Land Bridge as an example of the sort of excellent work the Survey sponsored.

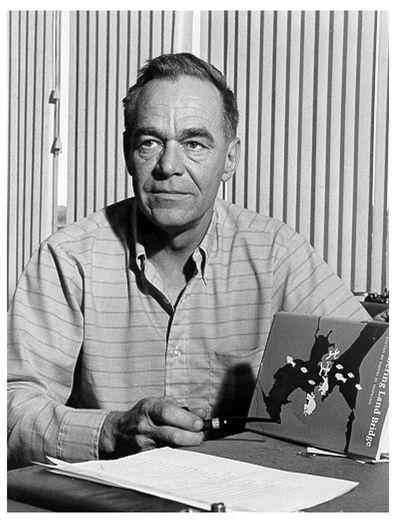

Hopkins upon the publication of his soon to be classic, The Bering Land Bridge (Photo by Gene Turner, courtesy of Dana Hopkins)

Under Hopkins’ guidance, the book fit together a number of Beringian puzzle pieces. Charles Repenning, working with mammal fossils, was able to identify three, possibly four surges of immigration over the Bering Land Bridge into the New World. At the time of the first influx identified by Repenning, about twenty million years ago, fossils—or to be more precise, the evolutionary adaptations evident in the fossils and inferred to have resulted from climate changes—suggested that the land bridge was warm-temperate, humid, and forested. During the second mammalian dispersal, around the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene, Beringia appears to have been temperate, humid, and still forested. By the time of the third pulse, in the middle Pleistocene, grasslands had taken hold, along with the forests, in a temperate climate. Not until the late Pleistocene did Repenning consider the mammal record to indicate Arctic conditions, with a flora dominated by tundra, steppe, and the scrubby northern forest called taiga.

Repenning observed another interesting fact originally noted by W. D. Matthews around the turn of the nineteenth century. Though mammals migrated across the land bridge in both directions, many times more species migrated from the Old World to the New. This may have had to do with the super-continent of Eurasia having vastly more east-to-west distance in the north temperate latitudes than does North America. Hence, discrete populations of Old World fauna could evolve separately, adapting differently to relatively similar environmental conditions over a wide area. With more varied adaptive strategies, Eurasian fauna were more likely to flourish as they dispersed across the land bridge into North America. By contrast, there was virtually no region of North America during the Ice Ages, except unglaciated central Alaska, in which boreal fauna could evolve—all the rest of North America’s northern lands being covered with glaciers.

Repenning’s findings made an important contribution to the book, as they corroborated the existence of the land bridge through the fossil record of land animals and added knowledge about the changing ecology down through the Ice Ages. Still, the geologist in Hopkins craved geophysical evidence of the land bridge, and two oceanographers named Joe Creager and Dean McManus delivered it up.

The Bering and Chukchi Seas are shallow—one hundred twenty to one hundred eighty feet—and the sea floor there is mostly flat. In fact, the continental shelf underlying the Bering Sea is one of the flattest and smoothest places on the planet. Its slope, at no more than three or four inches per mile, is almost unmeasurable. North of Bering Strait, the Chukchi Sea floor extends this barely submerged plateau some distance into the Arctic Ocean. Upon both sea bottoms a layer of marine sediment has filled in and smoothed out whatever topographic relief the bedrock underneath had when it was dry land.

In their chapter in The Bering Land Bridge, Creager and McManus reported having found the vestige of an ancient river at the bottom of the sea. They had drilled an ocean core through the sedimentary layer over one of the filled-in valleys in the Chukchi Sea south of Cape Thompson, near Point Hope. At the bottom of their core, they brought up sediments that were “brackish-deltaic in origin.” The deposit apparently marked the head of an ancient estuary formed by a river whose tributaries included today’s Kobuk and Noatak Rivers of Northwest Alaska, at a time when the sea stood about one hundred twenty-five feet below its present level. Radiocarbon dating put the material at twelve thousand to fourteen thousand years old. In other words, buried beneath the flat bottom of the sea, Creager and McManus had found a Pleistocene river valley. They called it Hope Seavalley. Hopkins called it “the clincher.”

Bathymetry (the topography of the sea bottom) interested Hopkins too. In the summer of 1965 he had joined a young USGS colleague named Dave Scholl and an Icelander named Thorleifur Einarsson on board the U.S. Navy ship Charles H. Davis to hunt for possible undersea canyons in the Bering Sea. Hopkins had roughed out a contour map of the Bering shelf from scanty data, and he and Scholl had spent many days poring over it. They wondered if some of the occasional “holes” (deep spots near the continental shelf margin) might be canyons, rather than completely enclosed depressions, and so possible remnants of ancient river valleys.

Steaming across these holes, the ship towed a sparker, which discharged electricity into the water such that its heat created a rapidly expanding bubble of superhot water vapor that sent a sound wave bouncing off the bottom and off other layers of sediment and rock beneath the bottom. Detection equipment picked up the returning echoes, and a profile of the sea floor showed up on a roll of seismograph paper. All the scientific gadgetry resided inside a windowless trailer bolted to the deck of the ship. For most of the stormy cruise, the ship pitched and rolled atop thirty- and forty-foot waves. Inside the laboratory, with no view of the horizon, Einarsson, the Icelander, was hopelessly seasick. But Hopkins, who does not get seasick, was having the time of his life. He spent nearly twenty-four hours a day in the trailer, his eyes glued to sweeping pens that profiled the sea bottom and underlying layers. “I could hardly go to bed. For the first time in my life, I was seeing these things in real time. It was like a feast to me.”

Bottled up in their heaving laboratory, the men discovered that the holes had outlets. They were canyons. Hopkins and Scholl explored three exceptionally large and long submarine canyons in the southeast Bering Sea at the edge of the continental shelf. One of them, Bering Canyon, was, at two hundred fifty miles in length, the longest slope valley in the world. It runs along the north side of Unimak, the most easterly of the Aleutian Islands. Another, called Zhemchug Canyon, south of St. Matthew Island, was likely the world’s largest slope valley volumetrically. Most of the large undersea canyons in the world have a volume of less than three hundred cubic miles. Zhemchug Canyon’s volume is greater than five thousand cubic miles. Pribilof Canyon, just southeast of St. George Island, is also one of the largest and longest of the world’s submarine canyons.

More particularly, the canyons did seem to be the drowned fragments of ancient river valleys. Hopkins and Scholl thought the canyons originated in the neighborhood of fifty million years ago with subsidence and down-faulting of the bedrock, before the depressions were filled in and covered with sediments. When the sea level was lower, sediment-laden glacial runoff of the great rivers of Alaska likely scoured the canyons. Hopkins and Scholl believed that Zhemchug Canyon represented the Ice Age mouth of the Yukon River. They thought the Kuskokwim River, as well as the Yukon, had at times flowed through Pribilof Canyon. And they believed Bering Canyon received its runoff from the glaciated highlands surrounding Bristol Bay and possibly from the Kuskokwim River as well. Another puzzle piece seemed to fit into place.

On the release of

The Bering Land Bridge in 1967, reviews from around the world streamed in to the offices of Stanford University Press. Hopkins’ file contains five German language reviews, three in French, others in Danish, Dutch, Russian, Swedish, and several in English (American and the Queen’s). They hailed it as “an extremely important reference,” “a most significant,” “valuable and fascinating book,” a “masterful job of editing,” “remarkably cohesive” and “readable.” Readable it was, especially Hopkins’ writing. The book opens lyrically and memorably with these lines:

Eighteen years ago, storm bound at Wales village, I studied the mist smoking over a turbulent Bering Strait and wondered who, on this violent day, might be shouldering the wind on the Asian shore to share my search for traces of the past. Near me rose a peaty mound, the midden left by generation upon generation of Eskimos dwelling at the western tip of North America; behind me rose Cape Mountain, scarred by ancient glaciers, carved by ancient waves. Perhaps someone was at that moment sheltering his Cyrillic notes from the mist as he huddled on a terrace on East Cape, at the eastern tip of Siberia—or in an Eskimo burial ground at Uelen, Siberia’s easternmost village.

Hopkins dedicated the book to his two Beringian exemplars, Eric Hultén and Louis Giddings.