13

THE FIRST AMERICANS

On Tuesday morning, November 3, 1964, Louis Giddings drove his Volkswagen bus north along the peninsula that separates Narragansett Bay from Mount Hope Bay in eastern Rhode Island. He was heading in to Providence from his house at Bristol, on the grounds of Brown University’s Haffenreffer Museum. Giddings was both the director of the Haffenreffer and Brown’s first professor of anthropology. He motored along a couple of miles of winding country road, then down four miles of highway before he entered Interstate Route 195, which bee-lines into Providence from the southeast. At three-fifths of a mile west of the Seenkonk-Rehoboth town line, Giddings’ VW bus came abreast of another vehicle traveling in the same direction. Ahead of both of them was an Army truck towing a jeep. A newspaper account does not state which driver lost control. What is known is that a sideswipe collision occurred that sent both cars careening against the Army vehicles. In what the state police would call a “spectacular” crash, the truck and attached jeep veered into an embankment, while Giddings’ bus flipped and skidded on its side for some one hundred twenty feet.

Kate Carlisle, Giddings’ niece attended Brown at the time. She said the bus had seat belts, but her uncle wasn’t wearing his. “We went to the junkyard after the accident to get some stuff out of the van, and the passenger’s side was totaled, but the driver’s side did not look too bad.” Tossed around inside the van, Giddings smashed his head, collarbone, elbow, and hands, at least. Carlisle remembers “many broken bones, ribs, punctured lung.” Nevertheless, Giddings fought his way back from the serious injuries. After five weeks in the hospital, his greatest worry was that his recuperation might jeopardize the coming summer’s field schedule. He was looking forward to “a joyous return to the Kobuk” and his diggings at Onion Portage, as he wrote in his memoir. “He looked like hell,” said Kate, “but he was so ready to come home. I remember the joy and anticipation of him finally being able to come home.” A couple of days before he was to be discharged to home care, Giddings got out of bed to walk the halls a bit. Apparently, the activity shook loose a blood clot. When it reached his heart, it killed him instantly, says his niece. “I remember being in total shock. I kept saying, ‘But he was coming home, how could he be dead?’ It was very sad.”

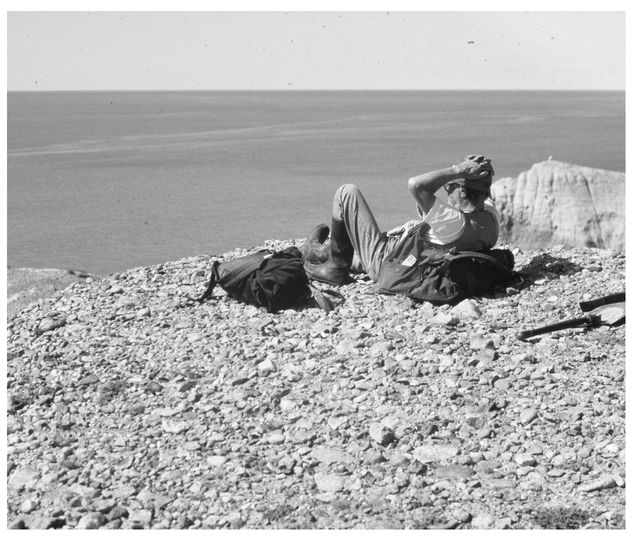

Louis Giddings, probably in the early 1960s, probably in Northwest Alaska (Photo courtesy of Laboratory of Tree Ring Research, University of Arizona)

Sad for the family, for the whole Arctic community, and for Hopkins in particular. Hopkins and Giddings had been at work on their second collaborative paper (this time joined by the geologist Troy Péwé), again blending the disciplines of geology and archeology. Giddings’ secretary and editorial assistant, Marjorie Tomas, wrote Hopkins on December 9, 1964, to say that she had just that morning been working on refinements to the abstract. “Before I finished, Mrs. Giddings called with the crushing news that Dr. Giddings died a few hours ago—a massive heart attack which could only be attributable to his injuries. My grief is too great to attempt any more with the abstract. Please do whatever you can with it. ...”

Hopkins at Nunyano, Chukotka, looking back across Bering Strait to Alaska, 1992 (Photo courtesy of Julie Brigham-Grette)

Hopkins rewrote the piece and offered Giddings’ wife, Bets, any help he could give. Because she was an anthropologist and her husband’s close professional associate, and to ensure the continuation of Giddings’ work and ideas, the university appointed Bets to her husband’s position as director of the Haffenreffer Museum. Brown also named Giddings’ former professor at both the University of Alaska and the University of Pennsylvania, Froelich Rainey, as overall director of the Onion Portage excavations. To direct the day-to-day dig, the university selected Giddings’ graduate student and field assistant, Douglas Anderson, with Bets Giddings to work as his field assistant.

Mrs. Giddings wrote Hopkins: “There are few to whom [Louis] talked so much about the scope of his work. You were the one geologist whose work and word he appreciated most.” She wondered if Hopkins could manage a visit to Onion Portage during the coming summer to help puzzle out the geology. Hopkins flew out to the Kobuk River, looked over the site, and wrote an outline of the geology for the Brown group. When they sought renewed funding to continue the dig, Hopkins helped there too, writing the National Science Foundation that he thought Onion Portage was one of the “most interesting and important archeological sites in Alaska” and that its excavation “must be pressed vigorously.”

By the time Doug Anderson had reached the bottommost cultural layer at Onion Portage, the excavation begun by Giddings had uncovered more than thirty cultural layers descending in distinct stratigraphy for an incredible eighteen vertical feet. Henry Collins, the Smithsonian Institution’s eminent Eskimo archeologist, called Onion Portage “undoubtedly the most important archeological site ever found in the Arctic.”

With his friend Louis Giddings gone, Hopkins took his questions about human migration to William Laughlin, whom he had known at Harvard. A physical anthropologist by training, Laughlin had worked among the Aleut people since he was of high school age, traveling to the Aleutian Islands with the famous physician-turned-anthropologist, Ales Hrdlicka. In the 1960s, at the time of his contribution to Hopkins’ first land bridge book, Laughlin was working on Umnak Island, at the eastern end of the Aleutian chain. During the glacial period, Umnak was the western terminus of an expanded and lengthened Alaska peninsula. More than that, because the water off the western tip of Umnak is deep just offshore, this portion of the island has nearly the same coastline now as it did when the last land bridge existed. Because it commanded the entrance to the Bering Sea, Laughlin says, Umnak was an ecological magnet, attracting both sea mammals and humans.

Laughlin thought that the mongoloid Asians—ancestors of the Aleuts and Eskimos—entered the land bridge as permanent residents, not as migrants making a crossing. Migration was the eventual effect, but so too was the establishment of permanent occupation, which Laughlin believes has persisted continuously to the present day. Coastal dwellers, without moving very far, could hunt on the land, the sea, and the rivers. After sea levels stabilized, they also had the great advantage of a rich and easily exploited intertidal zone. When the tide was out, sea urchins, limpets, whelks, mussels, chitons, clams, kelp, seaweed, and edible algae could be gathered in baskets, while octopus and some fish could be taken with a gaff hook or spear from the crevices in the exposed reefs. A simple technology of dip nets, set nets, fish spears, and hooks could account for abundant food. Moreover, the harvesting could be done by the least hardy members of the group: women, children, and old people. Most important of all, these sources of food were available nearly year-round, as recurrent as the tide.

Such a buffer against starvation may have afforded coastal residents of the land bridge the leisure to develop the use of boats, leading to what Laughlin calls “an engineering triumph”: the kayak. The coracle (a small, open, and rounded skin boat) or the umiak (a larger skin boat able to hold many men) permitted hunters to range out to the fringes of offshore islands. Here were additional intertidal zones and reefs, as well as fox-proof nesting cliffs for seabirds. The kittiwakes, eiders, cormorants, puffins, ducks, and gulls could provide hundreds of dozens of eggs, and feathery skins for lightweight and warm parkas. But the more seaworthy kayak, with its covered deck, permitted hunters to travel further, to chase and lance marine mammals, including the humpback whales, fur seals, sea lions, porpoises, and sea otters. “A natural progression of greater rewards for improved technology exists in the coastal area,” wrote Laughlin. “Each additional step, from strand hunting and collecting, through use of a simple coracle, through use of a boat with keelson (umiak), and finally to the kayak—and with it the culmination of open sea hunting—adds another series of exploitational areas.”

Laughlin was, above all, a human ecologist, says Hopkins. “His thinking has always been concerned with what the people were doing, what their resources were.” Hopkins says he learned by listening to what Laughlin knew, but also from what he did not know, by looking into the kinds of questions Laughlin asked him. Were there, for example, low, flat areas along the coast during land bridge times, marshy areas where migratory birds might fatten up? “He wanted to know what the productivity would have been along the shore of the land bridge because it’s his postulate that the Anangula [Umnak area] people were the most ancient known people of the Aleutians and that they dispersed along the shore of the land bridge.”

In Hopkins’ 1967 book, Laughlin observed the differences between the coastal Aleuts and Eskimos on the one hand, and the interior Indians on the other. Research into the morphology, serology, archeology, and linguistics of the two groups suggested to Laughlin that there had been two waves of migration across Beringia, one coastal and the other inland. But in the years since Hopkins has been closely involved in human migration researches, there have been some interesting convergences of thought. Notably, some workers in the fields of linguistics, genetics, and dentition (the study of teeth) suggest that there were not two, but three migrations over the land bridge. And that explanation fits pretty well with archeological and geological evidence.

Teeth turn out to be good indicators of a population’s history. Cultural traits, like a particular technique for knocking out stone tools, can be passed to unrelated groups and may not be indicative of a common genetic heritage at all. Even when these practices have not been exchanged between groups, there still can be remarkable resemblances in the fabrication of houses or of hats or of fishhooks simply because of the common objective, the similarity of materials at hand, and similar problem solving strategies. Genetic traits are much better indicators of relatedness, but even they are problematic. If a given trait depends on the inheritance of a single gene, and if it has a low frequency of occurrence in a population, then a small migrating band may not happen to include any individuals with that particular gene. Native Americans, for example, lack the B blood type, even though it is present in their presumed ancestral stock in Northeast Asia. The explanation may be that, just by chance, the colonizing band of migrants happened not to have among them anyone with the less frequently occurring B blood type, accounting for the trait not showing up today among their New World descendants. So the best clues are genetic traits that depend on many genes and do not change readily in response to use, diet, health, or other environmental factors. “Teeth,” says Christy Turner, who has studied the teeth of more than nine thousand skulls, “meet these requirements.” Teeth preserve extraordinarily well, outlasting bones. And teeth can be dated.

Back in the 1920s, when Laughlin’s teacher Ales Hrdlicka was analyzing the morphological traits of Native American bones, he noticed they frequently showed a “shovel” shape on the tongue side of the upper incisors. Ridges on the outside margins of those teeth give them the scoop shape of a square shovel. Turner found additional tooth characteristics that differ between groups but that do not change much over time. They include the number of roots, the number of cusps on the molars, a feature called Carabelli’s cusp on the first upper molar, and what he calls “winging” of the central incisors (where they are cocked at an angle to one another, rather than arrayed in a straight line, shoulder to shoulder). Different groups possess each of these traits to varying degrees. No single trait is diagnostic, but a groups’ dental signature can be defined statistically.

Turner finds two dental patterns among Mongoloid Asian peoples. The older one shows up in Southeast Asia between about seventeen thousand and thirty thousand years ago around the Sunda Shelf, a now submerged continental plain that formerly bridged the islands and the mainland of Southeast Asia. The Sundadont pattern, as Turner has named it, expanded along the coast into the islands of Japan. It also spread north and inland into what is today China and Mongolia. And this branch evolved a new dental pattern that Turner calls Sinodont. Sinodonts show more shoveling, winging, and three-rooted lower first molars than do the Sundadonts. The changes could have evolved in response to the colder, more stressful conditions of the north, says Turner, but more likely they were simply random genetic changes. In any event, he concludes that the dental evidence is clear: “the ancestors of all living Native Americans came from Northeast Asia.” Identifying this area as the ancestral locale of Native Americans was not original, but Turner’s arrival at that interpretation via dental evidence was.

Meanwhile, Stanford University’s Joseph Greenberg reached a similar conclusion following a completely independent line of inquiry. He relied not on what was in the mouth, but on what came out of it. A linguist, Greenberg had done monumental and widely acclaimed work sorting out the languages of Africa. Then he turned his attention to Native American languages, which probably numbered more than a thousand when Columbus landed. It seemed logical to investigators that the variety of languages had evolved from a single one spoken by the first pioneering inhabitants of the New World. Proponents of man’s great antiquity in the Americas considered that it would take as long as a hundred thousand years of residency for the root language to splinter into this bewildering array of distinct variations.

But Greenberg was less interested in trying to predict a rate of divergence than in classifying the languages according to their kinship. One early anthropologist, John Wesley Powell, the famous explorer of the Grand Canyon, had segregated fifty-eight families of Native American languages. Later investigators, finding more similarities, pared that number down, but not to the extent that Greenberg did. According to Greenberg, there were only three core languages. He applied a list of three hundred cognates (words held in common) to Native American languages. They were words unlikely to change much, like the words for body parts or grammatical parts, like first and second person pronouns. He found that there were enough interrelationships among the hundreds of Native American languages that they could be grouped into three families: Eskimo-Aleut, Na-Dene, and Amerind. The Eskimo-Aleut family contained ten languages, including Inuit-Inupiaq, spoken across the Arctic coasts from Alaska to Greenland; Yupik, spoken along the Bering Sea and North Pacific coasts; and Aleut, the language of the Aleutian Islands people. In the Na-Dene family group, Greenberg identified thirty-eight languages, including those of the Athabascan people of interior Alaska and northwest Canada, with outliers in California, as well as the related Navaho and Apache speakers of the American Southwest. The Amerind family includes all the other Native American languages spoken from Canada to the tip of Chile, over nine hundred in all.

Greenberg believes that the differences between the three linguistic groups is so pronounced, so to speak, that they must trace back to distinct Old World populations, and that each of these must have crossed the land bridge at a different time. The first migration should have been the Amerind linguistic group, because it occupies the southernmost geography (South America), and its languages are the least similar to those found in the Old World, having had more time to differentiate into local variants. Next to arrive must have been the Na-Dene family, which has a more southerly center of gravity than the Eskimo-Aleut family and which retains some connection with Asian languages, while having undergone more internal differentiation than Eskimo-Aleut. Last to cross into the New World, the Eskimo-Aleut family shows close affinities with Siberian and Old World languages and occupies the regions nearest the land bridge.

Of course, like toolmaking techniques, words can be borrowed by one culture from another, whether or not the two groups share common ancestry. However, for the most part, Greenberg’s linguistics-derived reconstruction of the migration fits nicely with Turner’s dentition-derived theory: three groups and three migrations. They differ as to who came second. Turner believes the Aleut-Eskimos arrived before the Na-Dene people.

Hoping to bring a third discipline to bear on the question, Greenberg and Turner teamed up with a geneticist named Stephen Zegura. Unlike language or toolmaking habits, the similarity of certain genetic traits necessarily indicates a shared ancestry, rather than a response to environmental conditions. Zegura looked at blood group antigens, serum proteins, erythrocyte enzymes, immunoglobulins, leukocyte antigens, and mitochondrial DNA, among other genetic material. The picture is not clear, he says, as to where the Amerind populations fit in genetically. The Na-Dene are problematic too, showing some affinities with the Amerind and some with the Eskimo-Aleut.

Zegura thinks his genetic data are supportive of the three-migration theory, though not confirmatory. He points to the long-term work of Robert Williams and coworkers as the best support from genetics. Williams’ team analyzed genetic markers from thousands of Native Americans. Those typed fell into two pre-European−contact groups. The first was comprised of Apache and Navajo (both Athabascan speakers). The second group included members of the Amerind, to use Greenberg’s term. That left the Eskimo, but they were not part of this study. The groupings produced by genetic typing led Williams’ team to concur that there were three migrations across the land bridge: paleo-Indians (Amerinds) first; Athabascan speakers (including the Navajo and Apache) second; and last, the Eskimo and Aleuts.

Another corroborating bit of evidence comes from considering how long it might have taken for today’s divergent dental patterns, language variations, or genetic traits to develop. It’s rather hypothetical, but the three specialists come up with similar timetables for the postulated three pulses of migration: around thirteen thousand years ago, around ten thousand years ago, and around four thousand years ago. And, they claim, this chronology matches up nicely with geological and archeological data. Geologically, they say the land bridge was in place before about ten thousand years ago (other researchers estimate the date of submergence to be eleven thousand to fourteen thousand years ago) for a period of perhaps fifteen thousand years (others think much longer), permitting migration without the use of boats, for which there is little evidence. Archeologically, Turner, Greenberg, and Zegura believe, the record is also supportive. Before people could migrate across the land bridge, they had to be established in Eastern Siberia, and until recently there was no record of human occupation east of Lake Baikal before twenty thousand years ago. Even a newly reported find of thirty-thousand-year-old tools in the Yana River Valley, while pushing back the earliest known date of human occupation of the Asian Arctic some sixteen thousand years, still places humans fifteen hundred miles from Bering Strait. Probably around fourteen thousand years ago, toolmakers linked to the Na-Dene were present at Diuktai along the Aldan River of Eastern Siberia, and they show up in Kamchatka at about the same time. They produced a range of implements, including bifacial knives and points, microblades likely inset into shafts, as well as bone and ivory artifacts.

Of course, not everyone agrees—about anything. Greenberg predicted that colleagues would greet his classification system with “something akin to outrage.” They did. Most experts denounced his methodology and conclusions. Even the least obstreperous of his critics consider Greenberg’s classification well out in front of the available evidence, as the discussion continues. Turner’s dental evidence likewise has holes in it or, as David Meltzer calls them, “cavities.” Turner’s groups are not discrete and internally consistent. Aleut teeth do not group as well with Eskimo teeth, where Turner places them, as they do with Na-Dene teeth, where he says they do not belong. Some Na-Dene teeth from coastal areas are less similar to Na-Dene from the interior than they are to Eskimo-Aleut teeth. As Meltzer writes, “So goes the dental evidence, neither a direct record of migration nor tightly linked to identifiable groups, nor (so far at least) producing internally homogeneous groups.” Ongoing work by Douglas Wallace and colleagues involving mitochondrial DNA indicates that Na-Dene are genetically distinct from Amerinds and that the Amerinds show a longer history of separation from Old World ancestral stock. Where the Eskimo-Aleuts fit is still unresolved. Wallace’s work does support Turner and Greenberg’s theory that Amerinds derive from a single pulse of Asian immigrants.

Regardless of all that might be learned from these studies, it is entirely possible that the very first Americans did not successfully establish themselves for the long term, that they died off without leaving a lineage, that they are ancestors to no one. In that case, neither their language, nor their teeth, nor their genes will show up in contemporary Native Americans. Only one science has a chance of uncovering relics of their residence in the New World: archeology.