CHAPTER 6

The Great Hall of Camelot struck cool in the midday heat. The sun poured through the windows, and fell in treams of molten gold to the gray-flagged floor. The rilliant light gilded the high white walls and lost itself n the soaring vault of the roof above.

In the center of the hall, brought back from the chapel after the vigil, the Round Table stood in all its glory, surrounded by the sieges of its one hundred knights. Twenty of the names picked out in gold on the wooden canopies overhead were fresher than the rest. Each of the knights who had kept the vigil in the chapel was now to receive his sword from the King, and take the seat at the table that he had striven so hard to win.

Many of the knights had already taken their seats. From his lifelong place, old Sir Niamh surveyed the new giltwork and was swept with a sense of loss. There, where the scrolled letters read “Sir Mador of the Meads,” was the siege where Rotho used to sit, his dear old friend-in-arms, and over there, the seat of the hot-tempered Tirzel, never liked, but oddly missed once he was gone. Rotho had died in the infamous Saxon attack, when the young prince Amir had been killed. Tirzel had perished ignominiously when an evil lord had thrown him down a well. Now strangers would take their seats, and young ones too. Unfledged boys, Niamh mourned, filling the place of men.

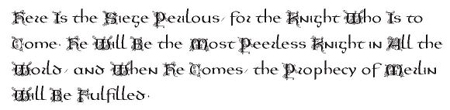

Yet one seat at the table was not filled. Niamh did not need to lift the red velvet cover over the canopy to read the gold letters that every knight knew by heart.

Niamh sighed. He could remember when Merlin had made this prophecy, from the depths of his crystal cave. A boy would come, the old enchanter had said, who would be the son of the finest knight in all the world. He was destined for the highest adventure of all. They must call his seat the Siege Perilous, for he would face many dangers, and defeat each one. He would become the best knight in his turn. And when he came, the table would be complete.

Of course they all thought it would be young Amir; who else? The Queen’s son, and so like his father that every movement, even the way he held his sun-blessed head, was Arthur to the life—no one in the world could have a stronger claim. And who could make a better knight at the table of the Great Mother herself than the Queen’s own son? It had all been perfect, a cause of heartfelt joy.

Too perfect, Niamh reflected grimly. Fate had seen to that. He fingered the thick gold torque around his neck, the only badge of knighthood before the Christians had brought in this foolery of suffering, vigils, and fasts. Was he the only one who remembered the glory days, the days of gold before Arthur came?

No, over there was Sir Lucan, a valiant knight of Queen Guenevere then, and onetime champion of the Queen’s mother before. And Sir Lovell, Lovell the Bold the women used to call him, still as handsome as ever, damn him, not a scar to be seen. Niamh chuckled. The new knights would do well if they managed half of Lovell’s triumphs with twice his wounds.

His eye roved on. Lovell was a hero, one of the old school, not to mention Gawain, Kay, and Bedivere sitting next to Dinant, Tor, and Sagramore, doughty warriors all. Sir Niamh sighed. Yet the Round Table needed new blood, there was no doubt of that. So it was right that the King and Queen were to make up a band of new knights today, with a fine feast to boot.

The King—

Sir Niamh frowned down the length of the Great Hall. Outlined against the whiteness of the far wall, Arthur sat enthroned with Guenevere in a blaze of gold and red. Above the dais was a canopy of scarlet silk, and on the wall above, their royal banners picked out in silver and gold, the crossed flags drooping limply from their poles. In the quiet space the Queen flamed in a crimson gown, with a cloak of white silk and a ruby-studded crown. To honor his new knights, Arthur wore the plain white tunic of knighthood over simple dark breeches and fine leather boots. Only his rich silk cloak of royal red and the heavy gold crown of Pendragon proclaimed him a king. The sun poured down like a blessing on his fair head as he gripped the arms of his throne, the lines of resolution visible on his face.

Sir Niamh felt a stirring around his heart. What a man Arthur was, what a king! That ever he should have had to suffer so, both him and the Queen! Niamh closed his eyes, and a heartfelt prayer rose unbidden to his mind: Goddess, Mother, spare them more misery, help the King.

AT THE HEAD of the hall Guenevere sat immobile on her throne and did her best to stifle unwelcome thoughts.

If Amir had lived, we would be knighting him now.

No, not yet, he would not be old enough.

But still—

She gripped the carved armrests of her throne in an unconscious echo of Arthur’s regal pose, and straightened up. She must not allow herself to envy Queen Morgause of the Orkneys, seated below her in the body of the hall. Tall and well formed, inclining to an ample fullness, Morgause shone like a midnight star in a gown of indigo velvet, with glittering sleeves. A white veil floated down from her headdress to wind around her stately neck and shoulders, and the crown of the Orkneys glittered on her head.

Behind Queen Morgause’s throne stood her knight, Sir Lamorak. She half turned, he leaned down toward her, and she whispered in his ear. He nodded, and a languorous smile passed over her face. In the same instant it came to Guenevere: These two are lovers; she has had him in her bed.

Morgause glanced up at Lamorak again, then her eyes sought her eldest son, Gawain. Seated at the Round Table, finely dressed in green and gold, relaxed in careless manhood, Gawain’s big body was almost beautiful, and Morgause’s gaze caressed him with a fierce maternal pride. Watching her, Guenevere was seized by such a pang of envy that she almost cried aloud.

She held her breath, and tried not to feel or think. Morgause had suffered much in her marriage, Guenevere knew. King Lot was crueler than the Saxon pirates, who crucified monks on their own church roofs and played football with unborn babies ripped from their mothers’ wombs. Yes, Morgause had suffered. But she had never lost a son. Least of all to the Saxons, men so cruel they would dig up a child from his grave to make his father grieve. So Amir had been buried on the seashore, where his small grave would never leave a sign. Where not a soul, not even his mother, could find it again.

A horde of wounding thoughts came down on Guenevere like a swarm of angry bees. And now I sit here childless, when I might have been like Morgause, reveling in a mother’s Joy. Even at seven Amir was so bright, so forward, so tall and bold that he would have been made a knight ahead of his time, perhaps even now, with the young knights here today.

And every one of them will remind me of him. Arthur will feel it too. Every sword stroke on every new knight’s shoulder will be a knife in both our hearts. There will never be a knighthood for our boy. The Siege Perilous will remain unfulfilled.

The first would be worst, they both knew that. The first young man who mounted the dais in his pure white tunic, scarlet cloak, and shining mail would be the sharpest reminder that if Amir had lived, he would have been this and more. Shivering beneath her cloak even in the warmth of the sun, Guenevere pressed her cold hands together and echoed Sir Niamh’s prayer. Goddess, Mother, be with Arthur and strengthen him now, help my dearest man—

A great fly buzzed against the window above her head. Guenevere shifted restlessly in her seat. Where were the novice knights? They had all been released from last night’s ordeal long ago, revived with strong cordials, given bread and hot meat. How long did the attendants need to give each one the ritual bath, and robe him in the white tunic of purity, and the red cape for the blood that he must shed?

“Your Majesties? The novice knights are here.”

Guenevere started. For all her impatience, the approach of the Chamberlain had taken her unawares. She caught Arthur’s eye, and he nodded impersonally. She bowed to the Chamberlain at her side. “Yes, we are ready,” she said. “Let the ceremony begin.”

The Chamberlain bowed, then turned and raised his staff. At the far end of the hall, the great double doors swung back. Waiting outside was the Novice Master, finely arrayed in checkered black and white. Beside him stood the first of the novices, his pale face burning like a candle flame.

Behind the Novice Master came the rest of the novices, walking in pairs. At the rear three mighty figures towered above the rest. Agravain, Gaheris, and Gareth were set apart from their fellows, as princes of the Orkneys, and close kin to the King.

The small procession drew up before the dais. Arthur reached for the sword at his side, and rose to his feet. Guenevere stood too, and put her soul into her eyes. Courage, Arthur, she willed him. I am with you, take heart, my dear.

Arthur felt her glance and turned. And I with you, his grieving look replied.

“Approach the throne, Mador of the Meads!” called the Chamberlain. White and quivering, the frail youth mounted the steps and knelt at Arthur’s feet.

The silver sound of trumpets pealed overhead. As pale as Mador and beginning to tremble too, Arthur drew Excalibur from its sheath. The great sword murmured sweetly in his hand. Arthur inclined his head. “Do your office, Chamberlain,” he commanded in a steady voice. “Require the oath.”

“Mador, do you swear to serve your liege lady Guenevere with your life?” cried the Chamberlain. “To honor your lord King Arthur with your last breath? To keep the Fellowship of the Round Table till your dying hour? To defend the weak, and give battle to the strong, and protect all women all your livelong days?”

Mador swallowed. His voice was a dry husk. “I swear.” He reached for Arthur’s hand, and brought it to his lips. Excalibur flashed through the air to touch Mador’s left shoulder, then his right, then his left again. Arthur’s voice was clear and strong. “Arise, Sir Mador, and glory be your name!”

The Novice Master stepped forward to pass a fine sword belt to Guenevere, with a slim gold and silver sword dangling from its side. “Draw near, Sir Mador,” she said.

For the rest of his life Mador never forgot the touch of the Queen’s hands, fluttering like butterflies as she buckled on his sword. He was trembling so violently that he could hardly stand, and his head was filled with her as with a bewitching scent. Dazzled, he saw the sunlight slanting on her still burning-bright hair, casting fragments of light into her slate-blue eyes. He heard her speak, but did not know the words. Yet his soul sang to the music of her voice like the harmony of the stars.

Guenevere stood on the dais and watched him cross to the Round Table to take his place. Mador, yes, I know who you are. The son of a poor lady from Marches, who has spent all her widow’s mite on sending her sons to be knights, to honor their own wishes and the will of her dead lord. You have a brother Patrise. . . . Yes, there he is, a younger, paler shadow of you, Mador, and the Gods know that you are pale enough—

Yet you are brave, you wear it in your eyes. You will do well. All my knights will do well.

The ceremony wore on. One by one the knights were dubbed.

“Arise, Sir—”

“Arise, Sir—”

At last only three large forms remained in the body of the hall. Guenevere saw Morgause sit up eagerly, murmuring to her knight, the rich blue velvet rippling over her heavy mother’s breasts as she watched her youngest, Gareth, moving down the hall. When he stepped up on the dais to receive his sword, Guenevere had to struggle to get the leather harness over his head, even though Gareth was shamefacedly trying to make himself as small as he could. She smiled to herself, and sadly acknowledged Morgause’s glowing pride in her four fine sons. The Orkney princes, Arthur’s nearest kin, were the only men at court who could stand shoulder to shoulder with him, and like him, block out the light.

Gaheris, too, had to stoop to receive his sword. Now only Agravain remained, standing alone. Guenevere glanced down and hardly knew what she saw. The eyes raised to hers were pools of black despair.

No, not despair, her racing heart rushed on, but a sucking, seething hollowness, empty of all but hate. Then Agravain’s face changed, and the hate was gone. With a downcast face and reverent air, he knelt before Arthur and bent his head. Arthur stretched out his arm, and Excalibur murmured faintly in his hand.

Suddenly Guenevere caught a sharp tapping sound from behind. Above her head, perched outside the high window, was a raven, peering in. Its hooked beak ended in a cruel tip, and its round eyes glistened with a blue-black sheen. As Arthur’s sword fell for the third time on Agravain’s shoulder, the hideous creature opened its mouth to crow.

Guenevere’s mind spun. A dark messenger from the Otherworld—Arthur must not see—

“Bow your head, Sir Agravain,” she instructed hastily. Somehow she fastened the sword around his long frame.

“May your Gods go with you, sir,” she wished him through cold lips, “and bring all your purposes to fulfillment, whatever they are.”

He raised his head, and his mouth formed a cynical smile. “They will, madam, they will.”

“You are one of the Fellowship of the Round Table now. See that you serve it well.”

As she spoke, a loud crack came from the center of the hall, followed by a groan, like life itself escaping from some mighty thing. To Sir Niamh it was as if the Round Table had let out a cry of woe. Gawain leaped to his feet, and supported the great wooden disk with both hands as he peered down to inspect the trestles below. “It’s only shifted on its base, there’s no danger here,” he cried out reassuringly. “You may carry on, sire, let the ceremony finish as planned.”

But another sharp rap from above distracted Arthur from his task. He turned to look up at the window, where the raven on the ledge had launched itself into a dance. Puffing up its chest and flapping its wings, it strutted to and fro, clacking with glee. At last it lifted the blunt wedge of its tail and triumphantly voided the contents of its body before launching itself into the air. Once, twice, three times it circled, darkening the sky, before winging straight into the sun, where it was lost from sight.

Arthur turned to Guenevere with an odd, strained laugh. “So, Guenevere, she has returned, it seems?”