- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

CAPE TOWN’S THREE PEAKS IN THREE DAYS

Instead of admiring Cape Town’s mountains from the city, flip things around and scale the Mother City’s peaks for a view of the skyline, hills and coast.

We stood, shivering, on Table Mountain’s famously flat top. A sense of achievement was in the air, and not just because we’d managed to ascend the mountain on a day when the infamous ‘Table Cloth’ was blissfully absent. The layer of thick cloud is renowned for its tendency to roll in and obliterate the vistas of Cape Town below. But our view was unobscured and for the third time that weekend we surveyed the city panorama far beneath our feet.

Over the past three days we had tackled the trio of peaks that watch over Cape Town – Lion’s Head, Devil’s Peak and Table Mountain. These are not the most daunting peaks in the world to scale. All three added together still fall short of South Africa’s highest mountain – and that in turn is half the height of Kilimanjaro. Yet climbing one, two or three of the peaks is a beautiful way to see one of the most beautiful cities in the world.

Hard-core hikers like to up the challenge by tackling all three peaks in one day, but for mere mortals, the hikes are best completed over the course of a weekend, interspersed with shopping, beach trips or long lunches in Cape Town’s side streets. And so, one Friday evening we joined the after-work crowd gathering on the road leading towards Lion’s Head.

© Alexcpt | Getty

the magnificent cityscape of Cape Town

It doesn’t matter what time of day you choose to ascend the 2195ft (669m) hill – you’re always going to have plenty of company. Early risers head up for a sunrise over the city, a steady line of hikers climb throughout the day and on a full moon the diminutive peak is packed with wine-toting walkers here to watch the sun set and the moon rise.

It’s only about an hour from the car park to the top, but just because it’s short and slap bang in a city, that doesn’t make the walk easy. There are vertiginous ledges, steep inclines and for those who crave a touch of adventure, a route that involves clinging on to ladders and chains manacled to the mountainside. If you’re a little queasy with heights, you can bypass the ladders – just keep an eye out for the sign marking the detour.

As the hike circles Lion’s Head, you get an ever-changing view of the city, the coast, the port, and once at the peak you can enjoy a vista that is considered by many to be superior to that from the top of Table Mountain, largely because the mountain itself is the central feature of the view. The downward scramble takes another hour and dusk is settling in when we head home to find a clean pair of socks for the next day’s hike.

© Petri Oeschger | Getty

hiking the path up Lion’s Head

Although when seen from afar Devil’s Peak seems to jut above Table Mountain, its jagged peak is in fact some 280ft (85m) shy of Table Mountain’s highest point. Of course, the main lure of all three of the peaks is the varied vistas over Cape Town, but there’s also plenty to see on the mountainside itself, particularly for botanists and flower fans. The whole Table Mountain range is layered with fynbos – indigenous shrub-like vegetation unique to the region – and the overgrown vegetation provides a little shade on an otherwise exposed route.

“As the hike circles Lion’s Head, you get an ever-changing view of the city, the coast, the port and Table Mountain”

It’s not just sun you’re likely to meet on Devil’s Peak – the mountain, much like the city it resides in, is notoriously windy and as we emerge at the 3287ft (1000m) summit we’re almost blasted back down to road level. It’s instantly obvious why everyone quickly retreats to the eastern side of the peak to crack open the picnic. Once sheltered from the wind, we munch on slightly soggy sandwiches and try to pick out landmarks in Woodstock, the southern suburbs and as far away as the Cape Flats.

It’s an out-and-back hike, and the loose gravel and sometimes steep incline make for a knee-jarring descent. By the time we’re back at the car, my legs are wobbling in a way that makes me very happy that on the final hike there’s an alternative way to get down the mountain.

There are many routes to the top of Table Mountain but we’re joining the shortest and most popular route, Platteklip Gorge. It’s a steep, 2-mile (3km) climb and admittedly isn’t the prettiest of the Table Mountain routes, but that’s not to say it’s an unattractive hike. There’s no disappointing way to reach the top of Table Mountain, particularly if the peak is free from clouds. I mean to count the uneven and occasionally enormous steps as we go, but after about 50 or so my mind wanders to more important things – photographing the slowly retreating city behind me, not tripping over loose rocks, keeping an eye out for dassies scurrying in the undergrowth.

© Bildagentur Zoonar GmbH | Shutterstock

a dassie watches on

We eventually emerge from the narrow gorge, but our climb is not quite done. You can’t really call it a peak unless you reach the highest part, so we walk the extra half-hour to Maclear’s Beacon. At 3563ft (1086m), it’s only 62ft (19m) higher than the upper cableway station, but it’s the principle of the thing that counts, so we save the celebratory high five for our arrival at the pyramidal pile of rocks marking Table Mountain’s apex. By this point I wish I had followed the ‘dress warm’ advice that I always offer to others heading up Table Mountain, but I had failed to bring anything more than a very light sweater and the wind is whipping straight through it.

It’s as good a time as any to join the queue for the cable car – the easiest and least knee-knocking way to descend. We might not have managed the Three Peaks in record time – the speediest to date is under five hours to scale the trio back-to-back – but at least the slow pace gives time to get back to sea level and enjoy the sights and bites of the city we’ve now viewed from every possible angle. LC

DASSIES OF TABLE MOUNTAIN

Wildlife along the three peaks is largely limited to lizards, bugs and birds, but you are fairly likely to meet a dassie, particularly on top of Table Mountain. Looking a lot like a big fat rodent, the fluffy mammals are actually most closely related to the elephant. Also known by the name of rock hyrax, the cute creatures hop between rocks and provide photographers with an adorable alternative to all those cityscape shots.

Ian Lenehan | 500px

elephants on the plains

ORIENTATION

Start // The Lion’s Head hike starts at the car park on Signal Hill Rd. The easiest route up Devil’s Peak leaves from Tafelberg Rd, a little further on from the starting point for the Platteklip Gorge hike.

End // All three are out-and-back hikes, or you can opt to take the cable car back down the Table Mountain section.

Distance // Lion’s Head 3 miles (5km); Devil’s Peak 5.3 miles (8.5km); Maclear’s Beacon via Platteklip Gorge 5 miles (8km); all distances are for a round trip.

Getting there // Cape Town airport is 11 miles (18km) from the city. The hikes are best reached by car or taxi – all are a short drive from the city centre.

What to take // The weather is extremely changeable so be sure to have a light rain jacket and warm layers plus sunscreen and a hat.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

SOUTH AFRICAN DAY HIKES

MALTESE CROSS, CEDERBERG

If you want to soak up the sandstone scenery of the Cederberg on foot, but are not quite up to an all-day scramble up precipitous rock faces, the Maltese Cross hike is perfect. Undulating but never steep, the three-hour round-trip walk takes in all that is best about the Cederberg – scuttling lizards, big blue skies, hardy endemic plants and weird rock formations. The usual turn-around point is the Maltese Cross, a curious monolith seemingly sprouting from the rocks scattered around it. If you’re feeling energetic – and you already have a permit – you could continue up Sneeuberg, the range’s highest peak at 6647ft (2026m).

Start/End // Sanddrif Holiday Resort

Distance // 4.3 miles (7km)

More info // Permits must be obtained in advance from Sanddrif

© Mark Hannaford | AWL Images Ltd

admiring the rocky landscape of Cederberg from beneath the Wolfberg Arch

SENTINEL PEAK, DRAKENSBERG

Also known as the ‘chain ladder walk’, this is not a route for the vertigo sufferer. After an initial steep climb, the path flattens out for a while, but the real challenge still awaits. Scaling the chain ladders up the sheer face of the Mont-Aux-Sources massif takes a bit of nerve, but there is an (admittedly steep) alternative if you just can’t face the two ladders. Once at the top, a fairly flat walk takes you above the Tugela Falls, the second highest in the world. Allow at least seven hours for the round-trip hike.

Start/End // Sentinel Car Park, Free State

Distance // 9 miles (14km)

SHELTER ROCK, MAGALIESBERG

Within easy access of Johannesburg, the Magaliesberg is a playground for outdoorsy Gauteng dwellers. Although dwarfed by the Drakensberg, the Magaliesberg has its own majesty thanks in no small part to the quintessential African panoramas viewed from mountaintops. Leaving from an adventure camp that also offers abseiling and rock climbing, the hike transports you to the top of the Magaliesberg range. There’s plenty of interest along the way, including glimpses of antelopes in the distance, Boer War relics, enough birdlife to have you whipping out your field guide and of course Shelter Rock itself, a very climbable hulk of ochre-coloured sandstone.

Start/End // Shelter Rock Base Camp

Distance // 5 miles (8km)

More info // Advance bookings are required and there is a fee to access the trail. Call +27 (0) 71 473 6298

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

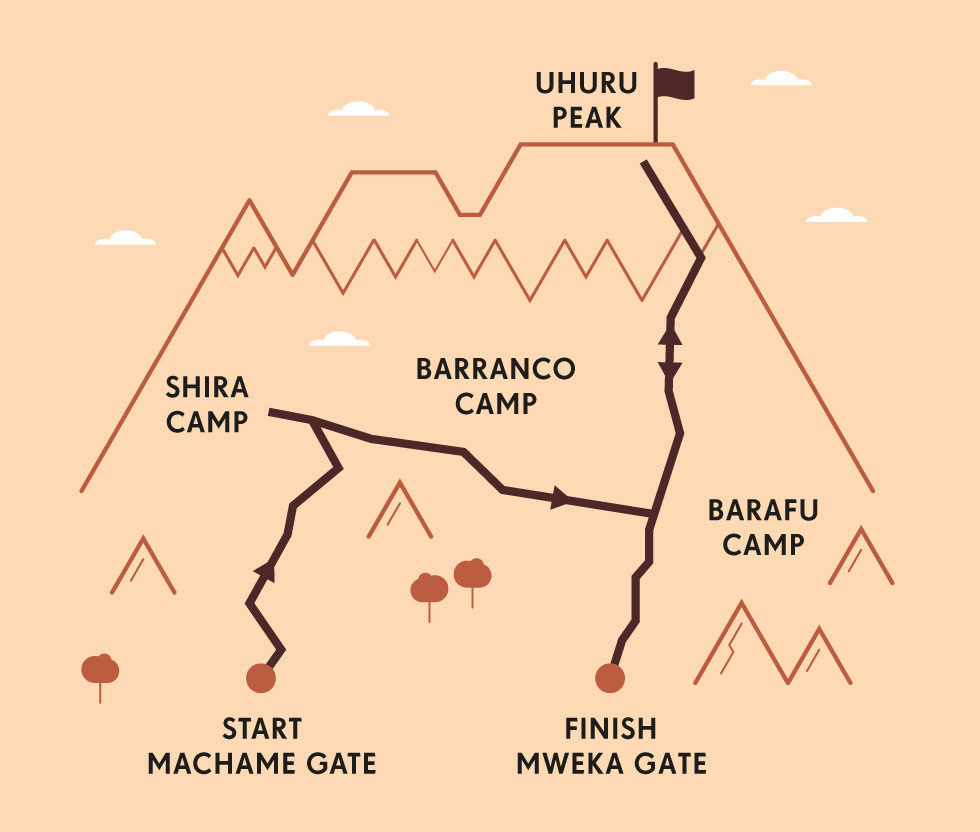

TOP OF THE WORLD: KILIMANJARO

Trek to the top of this mighty mountain in Tanzania for the greatest high you can get without crampons, and stand on the roof of Africa.

The wake-up call came a little before midnight – but I didn’t need it. I’d barely slept a wink. Part of me was relieved the moment had finally arrived: I wanted to get this over with. Another part could think of nothing worse: I didn’t want to get up because, beyond the safety of my sleeping bag, outside those tent flaps, the air was bitter-cold, perishing-thin and thick with impending doom.

Finally, steeling myself, I unzipped my warm cocoon and stepped out into my fears. Having climbed three-quarters of the way up Mt Kilimanjaro, it was time to make the final throat-scraping, limb-aching, head-mushing push for the top.

Four days earlier I’d set off as part of a group of 10 hopeful trekkers, accompanied by no less than 34 crew. This obscenely sized entourage of porters, cooks and guides was tasked with getting us to the top of Africa.

Kilimanjaro isn’t like other mountains. At 19,341ft (5895m), it’s the continent’s highest peak by far. It’s the world’s biggest free-standing summit, rising isolated and enormous from the Tanzanian plains. But it’s the mountain’s combination of huge heft yet relative accessibility that makes it unique. No technical climbing skills are required, so Kilimanjaro tantalises with possibility: mere mortals might reach the summit. ‘Might’ being the operative word…

It’s estimated that around 35% of the 30,000-or-so trekkers who take to Kili’s slopes each year fail to reach Uhuru (‘Freedom’) Peak, the mountain’s very highest point. ‘Many people are defeated from the start,’ head guide Samuel said as we set off pole pole (slowly, slowly) along the Machame route, the most popular and scenic of the mountain’s five main trails. ‘They see Kilimanjaro and think, “I can’t do that”.’

Many others, however, are defeated by the dizzying heights. Altitude sickness commonly kicks in above 11,500ft (3500m), and a high proportion of climbers feel some effects, from breathlessness, headaches and nausea to vomiting, confusion and, well, death. Kili is a ‘manageable challenge’ but not one to be taken lightly.

Our start was fairly tough, not because of the altitude – the trailhead was at around 5577ft (1700m) – but the morale-dampening downpour. It seemed churlish to moan, though. I toiled with only a daypack, while the porters dashing past in their cheap shoes lugged everything from paraffin canisters to folding tables and chairs.

© Ogen Perry | Getty

destination Kilimanjaro

After around six hours of walking through a rainforest that lived up to its name – rain dripped off the tree ferns and turned the path to chocolate milkshake – we reached our first camp, now at 10,500ft (3200m). Everything was soggy except our spirits: nothing brings a new band of brothers together like the sharing of both a common goal and bodily functions (flatulence is a curious by-product of altitude acclimatisation). We huddled and giggled in the dining tent, eating popcorn and pasta, listening to our crew’s soft Swahili songs float up to meet the drizzle.

The following days fell into a pattern. Mornings involved 20 minutes of psyching myself up to leave my sleeping bag, a quick ‘bath’ (a once over with a wet wipe), packing and repacking, a big breakfast. We soon trekked out of the forest zone, advancing into the moon-like upper slopes, oxygen becoming rarer with every stride. We walked amid phallic lobelia, tough everlastings, crumbled boulders and putrid long-drop loos. We rose higher, gaining views down on to the clouds and up to Kili’s ever-nearing crest. By the time we reached 15,000ft (4600m) Barafu Camp, our final base before our attempt on the top, I felt stinky, sunburnt and bunged up, but overjoyed.

Ian Lenehan | 500px

if nature calls at 15,000ft (4600m) Barafu Camp.

Then came our final briefing. ‘Tonight is not a good night,’ Samuel told us frankly. The summit climb is a steep, relentless schlep of almost a vertical mile. It’s about digging in; giving everything to cross the finish line. We would all likely find ourselves in dark places. ‘But self-confidence,’ he concluded, ‘all you need is self-confidence.’ In bed by 6.30pm, I lay wide awake, trying to believe in me.

“After what seemed like an age, I looked at my watch. I’d only been going for an hour. There were still five or six to go”

THE FALLING SNOWS OF KILIMANJARO

In 1849 Swiss-German missionary Johannes Rebmann became the first European to see Kilimanjaro. When he sent back reports of snow on the equator, scholars sneered; the president of the Royal Geographical Society declared it ‘a great degree incredulous’. But he was right. And Kilimanjaro, which sits just 3° south of the earth’s middle, is still topped by glaciers – just. Between 1912 and 1989, the ice cover decreased by 75%. Some scientists predict that it could be gone by 2030.

Uday Kiran Medisetty | 500px

above the clouds at Shira Camp

Thankfully, it was a beautiful night; freezing cold but windless, dry and star-spangled. At around midnight we joined the procession of head-torches curling up the mountain, falling into a steady robotic trudge. All was quiet save for the guides, who showed off by belting out pop songs. I wished I had the breath to sing; I wished I could escape the throbbing monotony inside my own head. With nothing to focus on but the heels in front and the darkness everywhere else, time was stretching out. And as the minutes dragged, so the ground steepened, the cold bit harder, the nausea yanked and the air thinned. After what seemed like an age, I looked at my watch. I’d only been going for an hour. There were still five or six to go.

It was at this point I gave myself a stern talking to. I either surrendered to the mountain – gave in, got beat. Or I surrendered to the challenge – stopped fighting and fretting, and simply got on with it; one foot in front of the other. Thus I shuffled on, moving slowly upwards. Eventually the minutes ticked by; the hours. The sky seeped from inky black to hazy purple to dawning pink. And then, finally, there it was, up ahead: the sign confirming our arrival on the roof of Africa.

The sun burst through the pillowy cloud below. I felt its creeping warmth. I felt relief. And I felt the beginnings of euphoria tugging at the sleeve of my fatigue. I wasn’t quite ready for it – I needed to get down this mountain first. But I had an inkling of just how good this moment was going to feel. SB

© Paul Joynson Hicks | AWL Images

another peak looms

ORIENTATION

Start // Machame Gate

End // Mweka Gate

Distance // Approximately 37 miles (60km)

Duration // Six to seven days

Getting there // Kilimanjaro International Airport is between the towns of Moshi and Arusha. The Machame trailhead is a one-hour drive from Moshi, two from Arusha. Climbing independently is not allowed – trekkers must have a guide or join an organised trip.

What to wear // Expect to be hot, cold and wet. Thermals, fleeces, T-shirts, a down jacket, waterproofs and hats (sun and woolly) are essential.

When to go // January to March and June to October, namely the drier seasons.

What to take // A head-torch, good sleeping bag and water purification tablets. Ask your doctor about Diamox, a drug that combats the effects of altitude sickness.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

AFRICAN HIGH PEAKS

MT KENYA, KENYA

Another great hulk of Rift Valley volcanicity, Mt Kenya is Africa’s second highest peak. It soars up to an impressive 17,057ft (5199m) but is often ignored by peak-baggers with their eyes on the bigger prize – climbing Kenya doesn’t have quite the same cachet as conquering Kilimanjaro. That’s a shame because Kenya is a fine climb: less crowded than Kili, richer in wildlife, arguably more scenic. Mt Kenya’s two highest summits – the sharp shards of Batian (17,057ft/5199m) and Nelion (17,021ft/5188m) – are for technical climbers only. Trekkers aim for 16,355ft (4985m) Point Lenana, conquerable in three days, though four is better for acclimatisation. The classic hike is via the Sirimon route, which ascends through wildlife-rich national parkland. Look out for elephants, zebra and other ungulates on the lower slopes, while the more alien upper reaches are home to shrieking rock hyraxes and various strange senecio and lobelia plants.

Start/End // Sirimon Gate (Sirimon route)

Distance // 33 miles (53km)

MT TOUBKAL, MOROCCO

Apex of the Atlas Range, 13,671ft (4167m) Mt Toubkal is also the highest peak in North Africa. You can get up and down it in two days if summiting is all that matters, but making a longer circuit not only helps with acclimatisation, it also offers a greater insight into local Berber culture. From the Imlil valley make a clockwise loop via walnut groves and cherry orchards, high passes and boulder fields, mud-brick houses and neat green terraces, wandering shepherds and wind-wizened juniper trees. The final ascent from the Neltner refuge is a stiff but steady clamber up scree, rewarded by views across a starkly spectacular landscape that the hardy Berber have made their own.

Start/End // Imlil

Distance // 45 miles (72km)

© soren-asher | Getty

Morocco’s Mt Toubkal, the tallest mountain in North Africa

RAS DASHEN, ETHIOPIA

The Simien Mountains National Park, a dramatic spread of 13,000ft+ (4000m) peaks dimpling northern Ethiopia, has been designated a World Heritage Site. And it is quite a sight: the basalt layers here have been eroded into striking escarpments, broad valleys, plunging precipices and spiky pinnacles, most notably 15,0157ft (4620m) Ras Dashen, the country’s highest point. The range is also home to rare and endemic gelada baboons, walia ibex, Simien foxes and Egyptian vultures, as well as ancient shepherd paths that provide plenty of exploring options. A classic route is to start in Sankaber (near the market town of Debark) to trek via the Geech Abyss and wildlife-abundant Chenek. The climb up Ras Dashen itself leads through giant lobelia forests and goat pasture, with an easy scramble to the summit for views over the Unesco-listed landscapes and to Eritrea beyond.

Start/End // Sankaber

Distance // Various

© robertharding | Alamy Stock Photo

a gelada enjoys the high life at Simien Mountains National Park

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

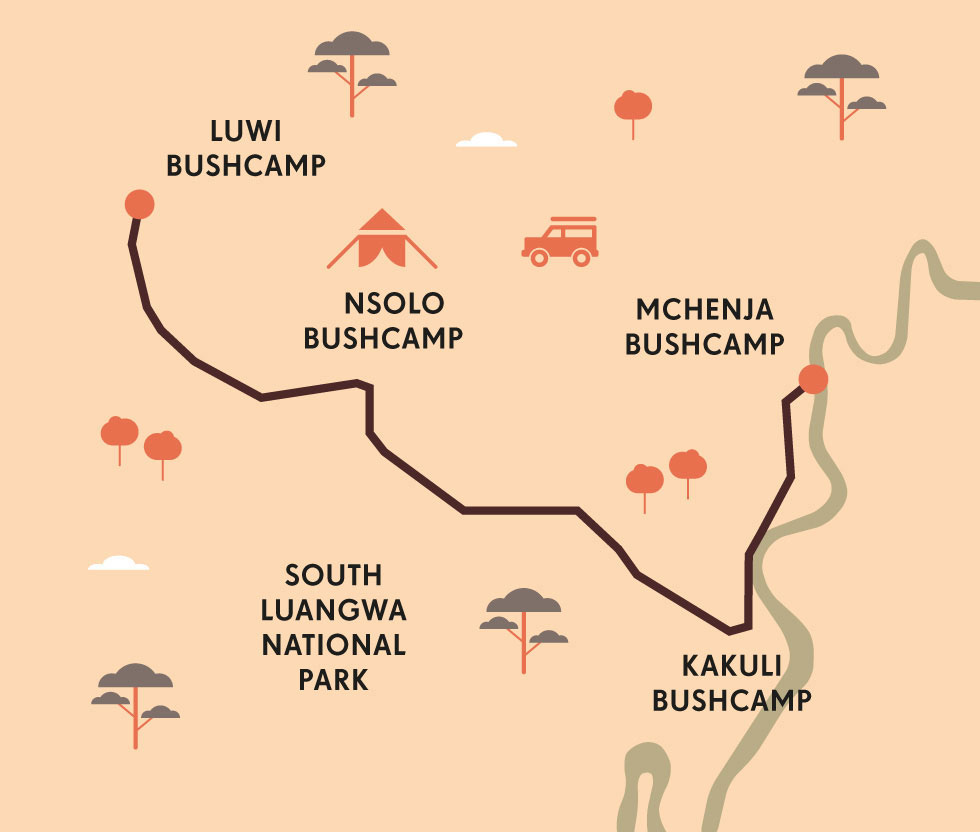

ANIMAL MAGIC: ZAMBIAN WALKING SAFARI

Delve into the raw African bush on a walking safari for electrifying encounters with elephants, lions and buffalo – and facetime with countless smaller species.

What does hyena smell like?

My Zambian guide, Abraham Banda, was in no doubt. Passing a clump of tall grass, he sniffed the still air then crouched beside the reedy stems. ‘Can you smell the scent?’ I knelt, and tried to look as if, well, obviously that unfamiliar aroma couldn’t be anything but… What, exactly? ‘Hyena. The males mark their territory by secreting that distinctive odour on to the leaves.’

Sniffing a whiff of scavenger pheromones – now, that’s something you can’t experience sitting in the cab of a jeep. It was just one of countless moments of connection with the African bush experienced only on a walking safari, where there’s nothing separating you from the natural world – no windows blocking vision, no engine noise drowning out growls or birdsong, no exhaust fumes masking scents.

I was enjoying Abraham’s impromptu lesson in aromatics on stage one of a three-day hiking safari in South Luangwa National Park. Zambia’s flagship wildlife destination is also the home of the walking safari, devised by near-legendary ecotourism pioneer and conservationist Norman Carr more than 50 years ago. Its mosaic of grasslands, lagoons and riverine woodland is a haven for creatures great and small, including four of the Big Five (rhino were sadly poached out across Zambia by 1998, though they’ve since been reintroduced). But what makes it a treat for wildlife watchers is the chance to roam its vastness on foot alongside some of Africa’s finest guides.

The dawn chill was evaporating as we set out from Luwi Camp on the first leg of our stroll between a quartet of bushcamps, roughly tracing the Luwi River to its confluence with the larger Luangwa. I say ‘roughly’ – we weren’t following a set trail, but instead relying on the expertise and experience of Abraham and our armed ranger, Johns. The emphasis was very much on quality, not quantity; distances are modest, measured in animal encounters, not miles or metres.

Within our first couple of hundred steps I was absorbing titbits of Abraham’s bush lore. The trunk of a young tree was bent double, half-snapped from the attentions of an itchy elephant; while along the path another bush showed signs of spoor – dried mud scraped on its side, marking a buffalo’s transit. Past that hyena-marked grass we found the scavengers’ droppings, flecked white with bone. Add a visit to a hippo midden, a teetering pile of dung at the water-horses’ al-fresco toilet, and the morning was a veritable poop patrol, topped off when Abraham broke open a football-sized elephant dropping to extract a marula nut. ‘They’re very sweet – good for jam,’ said Abraham, ‘and a lot easier to open once an elephant’s had a go at digesting them.’

We paused frequently: to laugh at warthogs, always comical, squealing and scattering before us; to examine the empty husks of lizard eggs, their incubation mound dotted with millipede tracks; to watch a snake eagle tearing at a monitor lizard in a branch above us. The gentle rustle of our footsteps was occasionally drowned by the whir as flocks of queleas and Lilian’s lovebirds took flight from a seed-laden patch of dust. And at this delightfully stop-start pace, by late morning we reached the dried-out bed of a tributary of the Luangwa River.

We sat out the dry, breathless African noon in the shade of a buffalo-thorn; bird calls had receded, the vivid carmine bee-eaters nowhere to be seen. The sandy riverbed was a virtual walk of fame where the stars of the park had pressed their prints – the dinner-plate pads of elephants, the cloven hoofs of giraffes and the tiny paw prints of elephant shrews framed within lion pugmarks – but the animals themselves were elsewhere.

© Ian Cumming | Getty

eye-to-eye with a giraffe

Then to our left, I spotted a movement: a young lion padded around a bend in the riverbed and headed straight for us. As it advanced, another juvenile appeared behind, and then two more: 300 yards away, 200, 100… they flowed towards us with liquid grace, and Johns tightened his grip on the rifle, as Abraham weighed up the approaching predators.

© Philip Lee Harvey | Lonely Planet

lions at rest

“A young lion padded around a bend in the riverbed and headed straight for us. Another juvenile appeared behind”

OLD BULL BUFFALO

Born in what’s now Mozambique in 1912, Norman Carr worked as an elephant control officer in Northern Rhodesia (today’s Zambia), but in the 1940s virtually invented eco-tourism. In 1950 a local chief granted him permission to establish a reserve on the Luangwa River, and during the 1960s ‘Kakuli’ (‘Old Bull Buffalo’), as he was nicknamed, developed walking safaris. A vocal proponent of conservation, Carr – ever adamant that local people should benefit from tourism – established one of Africa’s finest guide-training programmes.

Seconds later, the increasing tension was broken as two of the lions decided it was time for fighting practice. A halo of dust rose around the young animals as they collapsed on to the riverbed, rolling, nipping and growling softly while their companions stood haughtily watching, clearly considering themselves above such childish shenanigans. Then some movement from our group betrayed our presence; the lions froze and sniffed the air before leaping on to the far bank and evaporating back into the brush.

© Will Burrard-Lucas | NaturePL

That day’s hike was punctuated by such big encounters and small incidents, each providing a better appreciation of the park’s varied habitats. Mopane and acacia stands lined the river across which echoed the gutsy guffaws of male hippos. In scrubby grassland we passed herds of buffalo, jumpy impala, waterbuck and puku. Elephants materialised anywhere, at any time, herds rumbling across the plains, browsing branches and gathering at the river’s edge.

© Philip Lee Harvey | Lonely Planet

in South Luangwa you’ll find elephant, zebra and southern carmine bee-eater.

And there were plenty more aromas to enjoy. As we approached the Nsolo Camp late that afternoon the fragrances of African lavender and sage faded and the scent of baking potatoes wafted towards us. Dinner?

© Nick Garbutt | Getty

‘That’s not the camp kitchen,’ smiled Abraham. ‘It’s the smell of the potato bush.’ As we ambled into camp after seven captivating hours, serenaded by the calls of turtle doves urging us to ‘Drink harder! Drink harder!’, my brain was whirling with the addition of yet another nugget of wilderness wisdom. So it continued, day by day, and step by step. A Zambian walking safari packs in more magic moments per mile than any other hike. PB

© Donvanstaden | Getty

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Various bushcamps, mostly in the Mfuwe sector of South Luangwa National Park

Distance // Not more than about 7.5 miles (12km) each day

Getting there // Safari companies pick up guests from Mfuwe Airport, a one-hour flight from Lusaka (Zambia’s capital) or Lilongwe (Malawi).

Tours // Various companies offer walking safaris between their camps in the park. The best-known and longest-established include Norman Carr Safaris (https://timeandtideafrica.com/norman-carr-safaris), Robin Pope Safaris (www.robinpopesafaris.net) and the Bushcamp Company (www.bushcampcompany.com).

When to go // June to October, during the cooler dry season – animals and birds seek out water, ensuring excellent wildlife watching.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

AFRICAN WALKING SAFARIS

GORILLA TRACKING, BWINDI, UGANDA

The total population of mountain gorillas is tiny: fewer than 900 are believed to survive in the Virunga Mountains straddling DR Congo, Rwanda and Uganda, and in the latter’s Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. Whacking up through the lush, dense vegetation of Bwindi to locate one of the habituated family groups is not for softies: it’s steep, it’s muddy, it’s overgrown, and it can be wet, cold, hot, or all three in one day. Until recently, limited numbers of permits costing US$600 per person allowed visitors to spend up to one hour with a family (if you can find them). But you can now join rangers habituating new groups, and enjoy gorilla company for several hours.

Start/End // Depends on the family being tracked, but treks usually depart from park headquarters

Distance // Various

More info // Habituation experience permits cost US$1500 per person. www.visituganda.com

© Steve Holroyd | Alamy Stock Photo

a gorilla in the midst of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, Uganda

MASAI MARA CONSERVANCIES, KENYA

Kenya’s most famous game-viewing area, the Masai Mara National Reserve, hosts the great migration of some 1.5 million wildebeest, zebra and Thomson’s gazelle each August to October, but also a permanent array of large herbivores and the predators that stalk them. But whereas the reserve itself can get woefully crowded with jeeps ringing lion kills, surrounding private conservancy areas offer equally fine wildlife watching, with the boon that walking safaris – forbidden in the reserve proper – are permitted. Join an expert Maasai guide and spotter to roam the bush savannah of Mara Naboisho Conservancy and witness the secondary wildebeest migration through the Loita Hills, watching for elephant, giraffe and lion.

Start/End // Conservancies set up for walking safaris include Naibosho, Mara North, Olare Motorogi, Ol Kinyei and Siana Group Ranch

Distance // Various

More info // www.expertafrica.com

© Eric Reitsma | 500px

wildebeest migrating through the Masai Mara

NYALALAND TRAIL, KRUGER NATIONAL PARK, SOUTH AFRICA

Kruger is known as a terrific destination for self-drive camping safaris, but to really get under the skin of the park and its diverse wildlife, join one of the official three-night Wilderness Trails guided tours. Based in a small, rustic camp on the Madzaringwe River, overshadowed by the looming Soutpansberg Mountains, you’ll be among just eight guests led out on consecutive days for hikes among baobab trees to spot both the biggest game – including lion, leopard, rhino, buffalo and elephant – and local specialities such as spiral-horned nyala and Sharpe’s grysbok, or prized birders’ favourites Verreaux’s eagle and Pel’s fishing owl.

Start/End // Punda Maria Rest Camp

Distance // Up to about 12 miles (20km) each day

More info // www.sanparks.org