- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

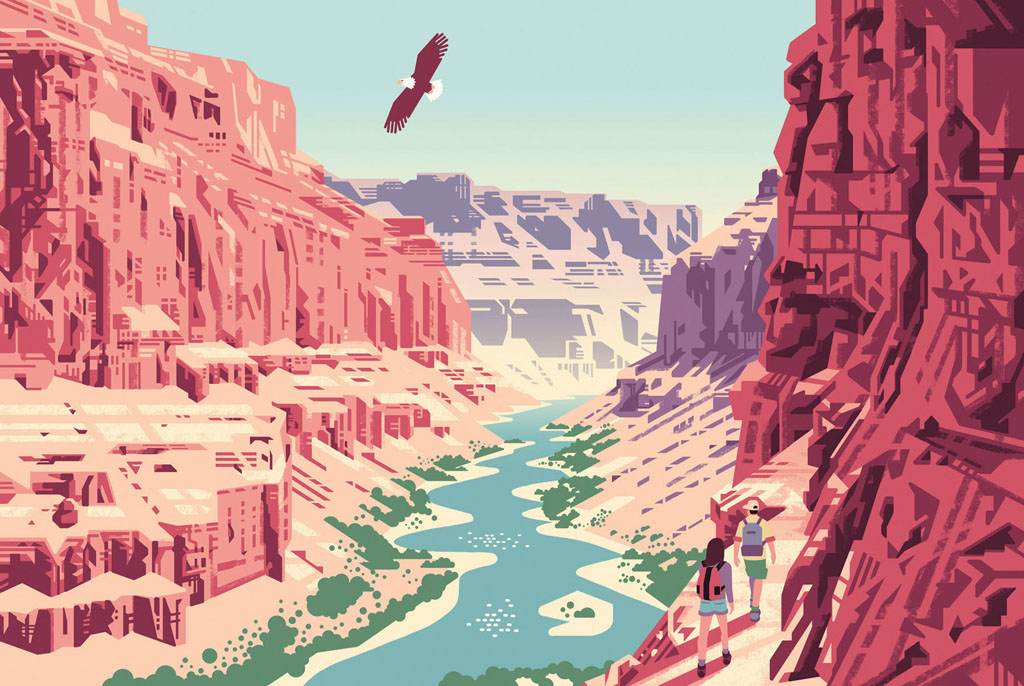

A WINTER DESCENT OF THE GRAND CANYON

An off-season Grand Canyon geology class offers fresh perspectives on the USA’s most iconic national park, from snow on the canyon rim to improvised riverbank saunas.

For geologists, there’s no place on earth like the Grand Canyon. Nearly two billion years of the planet’s history are encapsulated in the canyon’s mile-high jumble of fossil-laden rock layers, allowing scientists to take a mesmerising walk back through time.

Alas, science was never really my thing. Even the simplest paragraph in a made-for-dummies textbook went in one ear and out the other. Still, universities have their expectations, and mine wanted me to complete three science classes before graduation. So when I saw ‘Geology of the Grand Canyon’ listed among the autumn course options during my sophomore year at Stanford, it was like manna from heaven.

© Sandeep Thomas | Getty

cloud fills the Grand Canyon as seen from Yaki Point

Taught by two long-haired graduate students, this course’s big appeal was that its weekly classroom sessions would be complemented by a semester-ending Thanksgiving trek under the full moon into the depths of America’s greatest natural wonder. I signed up on the spot. Two months later, on a chilly late-autumn evening, I found myself driving through the night from the San Francisco Bay Area to the canyon’s South Rim, serenaded by the Grateful Dead in a car full of like-minded renegades.

We arrived just as dawn was sending red shoots through the steely November sky, illuminating a couple of inches of snow on the canyon rim and the endless folds of the chasm beyond. Starting from the New Hance trailhead, we were to chart a precipitous 7-mile (11km) course down to the Colorado River via the Red Canyon ravine, returning via the more gradual Tonto and Grandview Trails. Our instructors had chosen this route – one of dozens that descend into the canyon – because of its varied geological interest and its relative efficiency in reaching the bottom. The pitfalls of this approach soon became apparent: this entire first day would be down, down, relentlessly down from rim to river. (For several weeks afterwards, the toll on my knees was palpable; as even climbing a simple staircase back home became excruciatingly painful.)

Once you get below the rim, the world changes. Sheltered from the harsher conditions of the high-altitude Colorado Plateau, the trail soon exited the snow and we entered a world of layered desert landscapes, where the intricacies of Kaibab limestone, Coconino sandstone and Bright Angel shale we had seen traced on the classroom blackboard suddenly emerged into vivid real-world focus. The canyon, so huge and limitless from above, took on greater intimacy as we stair-stepped down into it, winding between piñon- and juniper-dotted rocky outcroppings and losing sight of the Colorado River. Here, the manifold colours of the canyon walls – reds, whites, greenish-greys, creams, oranges and ochres – became charged with more tangible meaning as we came face to face with them, a layer at a time.

© Matt Munro | Lonely Planet

standing on the edge of one of America’s epic sites

After hours of dogged descent, we finally reached the river at Hance Rapids, setting up camp above a sandy beach at the foot of a jagged red-rock pinnacle. Down here, the early winter sun managed to nudge the thermometer to around 15°C (60°F) and some of us were tempted to take a dip. But with the river temperature below 4°C (40°F), even a quick swim bordered on the suicidal; I paddled about two arms’ lengths into the water before reconsidering and racing to shore, my innards converted instantly to ice cubes. Later, as sunset yielded to a full moon, casting eerie illumination over the river and surrounding desert, our instructors constructed an impromptu sweat lodge from the coyote willows lining the river bank, and we took turns getting overheated and refrozen on repeat journeys between the sauna and the river.

Our day on the bottom was filled with teachable moments, as the canyon itself became an impromptu classroom. Along with exploring the beaches, climbing the pinnacle above camp and rustling up a pale imitation of a Thanksgiving dinner, we passed the time discussing geologic esoterica like Vishnu Schist and the Great Unconformity, while recuperating for the long climb ahead.

“The canyon, so huge and limitless from above, took on greater intimacy as we stair-stepped down into it”

ROUTE MANOEUVRES

Ready to plan your own hike into the canyon? There are nearly two dozen routes to choose from, each with its own appeal. For first-timers an obvious choice is the well-maintained and relatively shady Bright Angel Trail, equipped with two ranger stations and frequent potable water sources. For something more off-the-beaten-track, head to the canyon’s less accessible North Rim. Wherever you hike you’ll need a permit, which should be reserved four months in advance at www.nps.gov.

© RooM the Agency | Alamy

the South Rim’s Bright Angel Trail.

The next two days would be spent relentlessly slogging back uphill from 2608ft (795m) to 7400ft (2255m). (Exiting the canyon in a single day is generally out of the question, except for the supernaturally fit or the borderline insane.) Our plan was to make an intermediate overnight stop at the 4900ft (1493m) Horseshoe Mesa, a hulking semicircular rock outcropping where prospector Pete Berry struck a rich vein of copper in 1890 and founded his legendary Last Chance Mine.

Signs of the region’s mining history appeared everywhere as we passed through the imposing cliffs of Redwall limestone at the base of the mesa. Openings in the hillside hinted at the 19th-century mine shafts just below, while rocks flecked with dazzling blue and green crystals of azurite and malachite littered the trail’s edges, reminders of the eternal appeal of glitter to the human eye. Our last night in the canyon was spent in moonlit exploration, wandering past the foundations of abandoned mine buildings to the mesa’s far northern reaches, where the now-distant Colorado River could be seen dimly sparkling in hallucinogenic half-light, 2300ft (701m) below.

Another day, another climb. Our final exit route to the canyon rim retraced the steps of the mules that were employed to haul copper off Horseshoe Mesa up to Pete Berry’s Grandview Hotel. The hotel is long gone, but the route remains. Feeling a bit like overburdened mules ourselves, we headed back up through the familiar Coconino, emerging again at the snow-covered rim where our trip had started four days before – exhausted, elated and ready to do it all again. And maybe, just maybe, having learned a little something about all those beautiful rocks. GC

ORIENTATION

Start // New Hance trailhead

End // Grandview Point

Distance // 21 miles (33km) round trip

Getting there // The nearest domestic airport is Flagstaff Pulliam Airport (FLG), 84 miles (135km) away; international flights come into Phoenix, 228 miles (366km) away.

When to go // April, May and October.

Where to stay // The National Park Service operates lodges on both the South and North Rim. For lower-cost accommodation, camp or look further afield.

What to take // An animal-proof food container, water-purifying supplies and plenty of water.

What to wear // Dress in layers for the large temperature variations between the rim and river.

More info // www.nps.gov/grca/index.htm

Things to know // Reserve your trail permit months in advance, or be prepared to wait several days for the limited supply of ‘first come, first served’ permits issued on site.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

OFF-SEASON CLASSICS

INCA TRAIL, PERU

The Inca Trail to Machu Picchu is a perennial rite of passage for every would-be South American explorer. The iconic four-day trek is deservedly the stuff of legend – crossing two 13,000ft (3962m) passes, traversing ancient Incan steps and tunnels, and visiting other magnificent ruins en route to breathtaking views of Machu Picchu at dawn through the Gate of the Sun. Peruvian government efforts to safeguard the trail have resulted in new restrictions limiting access to 500 people per day, which means that permits for the dry-weather months of May to October typically book up months in advance. If you’re willing to put up with slightly less dependable weather, consider a trip in the off-season, when trails are quieter and competition for reservations less daunting.

Start // Km 82 along Río Urubamba railway from Cuzco

End // Machu Picchu

Distance // 27 miles (43km)

More info // www.incatrailperu.com

MT TEIDE, TENERIFE, CANARY ISLANDS

At 12,198ft (3718m), Spain’s highest mountain is an enjoyable and surprisingly rigorous summer challenge, but outside high season, when the Parque Nacional del Teide’s four million or so annual visitors trickle down to manageable numbers, it comes into its own – particularly in early spring, when the lower slopes start to bloom in flowers and, if you’re lucky, the summit area still has a hat of snow. The ascent to the volcano’s peak is the real challenge, especially if you opt for the very tough six-hour hike, but if weather or lung-power make this impossible, the cable car will still give you the views, and the park’s 73 sq miles (190 sq km) plenty of other enjoyable hikes. The Unesco site protects nearly 1000 Guanche archaeological sites and contains examples of 80% of the world’s different forms of volcanic formations, as well as 14 plants found nowhere else on earth.

Start // Montaña Blanca

End // Peak of El Teide

Distance // 10 miles (16km)

More info // www.telefericoteide.com

FAIRYLAND LOOP, BRYCE CANYON NATIONAL PARK, UTAH, USA

For another off-season take on the rare beauty of the American Southwest, head for Bryce Canyon National Park in winter. Nothing enhances the fairy-tale quality of Bryce’s multi-hued, whimsically sculpted hoodoos (rock spires) like a dusting of newly fallen snow. The red rock, evergreen trees and frosty whiteness combine to create a classic Christmas card colour scheme during the winter months, while the trails themselves are nearly deserted – in stark contrast to summertime, when the annual influx of visitors from the USA and abroad, coupled with helicopter sightseeing flights, can make the place feel like a theme park. The Fairyland Loop takes in some of the park’s most gorgeous scenery, including Sunrise Point, Fairyland Canyon, China Wall and the otherworldly Tower Bridge. Verify trail conditions with rangers before setting out; foot traction devices are advised in icy weather.

Start/End // Fairyland Point, Bryce Canyon National Park

Distance // 8 miles (13km)

More info // www.nps.gov/brca

© Dennis Frates | Alamy

winter snow settles on the spectacular hoodoos of Bryce Canyon National Park

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

TREKKING THE ‘W’ IN CHILE

Expect the unexpected in this climatically challenging but rewarding backcountry trek past glaciers, lakes, plains and peaks, including the magnificent blue towers of Torres del Paine.

If there’s one thing you learn hiking in the mountains of Torres del Paine, it’s that there isn’t one kind of wind; there are many, and none is quite like another.

There are cool breezes and gentle zephyrs. There are soft drafts and sudden gusts. There are whirlwinds that sneak up out of nowhere, whipping dust from the trail and snatching maps from your hands. There are keening squalls that scream down from the mountains, knifing through jackets and chilling fingers to the bone. And then, there’s the general, all-purpose kind of wind, the one for which Patagonia is notorious – a persistent, obstinate wind that never disappears, even on the calmest of days, and which, without any warning, can accelerate from mild to murderous. It’s my first day on the W, and I reckon I’ve already experienced all of them, and a few more besides.

Stretching for 44 miles (71km) across the southern half of Torres del Paine National Park, the W is Patagonia’s most celebrated hiking route. Its name comes from the fact that it forms the rough outline of a letter W, looping from Laguna Amarga in the east to Lago Grey in the west. It’s a five-day route that affords access to some of South America’s wildest mountain scenery – razor-edge mountains, wind-scoured valleys, tawny pampas and icy glaciers. It deserves its reputation; few places feel quite as raw, or wild.

© Scott Biales | Shutterstock

that top-of-the-world feeling at Lago Grey

Most hikers tackle the trail from east to west, but I’m walking in the opposite direction, as I want to end my journey by watching sunrise over the Torres del Paine, the rock towers after which the park is named. Unfortunately, Patagonia’s capricious weather means there’s no guarantee they’ll be visible by the time I get there – but there’s little point worrying about that now.

I spend my first day tracking the left line of the W, following the shores of Lago Grey, a glacial lagoon formed by meltwater from the Grey Glacier, itself an offshoot of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field. I look out over one of the glacier’s tongues as it melts into the lake, calving into icebergs or fracturing into columns that collapse with a boom and splash. Like most of the world’s glaciers, the Southern Patagonian Ice Field is melting fast due to climate change; on average, thinning by 6ft (1.8m) per year.

I spend the night at a rustic refugio, or mountain hut, near the lakeshore, before pushing eastwards towards the middle of the W. It’s a long, tiring trek: through swaths of land scarred by bush fires, along the blue sweep of Lago Pehoé and Lago Scottsberg, over the wild creek of Rio Frances and under Los Cuernos (The Horns), a chain of summits along the valley’s eastern edge. I pitch my tent among twisted lenga trees as darkness falls and the wind whines around the mountaintops.

“I pass a sign on a ranger’s hut: ‘Do not ask about the weather today,’ it reads. ‘This is Patagonia. We do not know.’”

Day three covers the middle line of the W: the Valle Francés or French Valley, supposedly one of the most scenic parts of the trek. Unfortunately, the weather has noticeably worsened. Dense black cloud squats over the mountains, and the wind has become a gale, hurtling down from the mountains and scouring scree from the trail. Occasionally the cloud splits and peaks briefly materialise from the murk – Fortaleza (the Fortress), La Espada (the Sword), La Hoja (The Blade). But by the time I reach the glacial cirque at the valley’s head, I’m in a whiteout, and the bitter wind and rain force me to beat a frustrated retreat.

The weather feels equally grim on day four as I follow Lago Nordenskjöld east towards the towers. I pass families of guanacos, the wild cousin of the llama, huddling together for shelter against the biting wind. Spindly trees shiver and rattle against the steel-grey sky, and the wind sends ripples and eddies through the yellow pampas. All I can do is plod on, head down, bent into the wind; the W has become a test of endurance as much as fitness. I pass a sign nailed on a ranger’s hut: ‘Do not ask about the weather today’ it reads. ‘This is Patagonia. We do not know.’ I boost my spirits with a snack of wild calafate berries; a legend says that anyone eating the sweet fruit is sure to return to Patagonia, but right now, I feel like I’d rather be anywhere than here. By the time I pitch camp that night at Campamento Torres, I should be able to see the towers from my tent, but there’s no sign of them. The mountains are locked behind a wall of cloud. As I fall asleep, listening to the gale buffet and batter against the walls of my tent, I feel gloomy. It looks like the Patagonian weather might get the better of me after all.

© Ugo Mellone | 4Corners

a puma keeps watch

However, the next morning, miraculously, the wind has completely dropped. There’s not the faintest breath of a breeze. The mountains are quiet and still, and the night sky is clear, illuminated by the star-spangled arc of the Milky Way. Elated, I pull on my boots and half-walk, half-run along the trail. By the time I reach the base of the towers, daylight is breaking over the mountains. I round a corner, and there they are: the mighty Torres themselves, high, craggy and tall, soaring skywards like a cluster of Saturn rockets.

I watch sunlight spill over the valley. Slowly, the towers blush, then glow, then glare, and soon enough they’re blazing, bright as pokers pulled from a furnace. Gradually, they turn yellow, then grey, then smoke-blue, like shards of metal cooling, and I finally understand their name: in the local Tehuelche dialect, Torres del Paine translates as the Blue Towers. And then, of course, this being Patagonia, the weather makes its presence felt: the breeze picks up, the cloud rolls in, and the towers vanish into haze.

© sylvain cordier | Getty

trekking ever upwards.

As I trudge back through the Valle Ascensio – the Valley of Silence – I reflect on how fitting its name is. Like me, every single hiker I pass seems to be utterly lost for words. OB

ANIMAL MAGIC

Torres del Paine National Park is one of the last strongholds for the wild puma in South America. A relation of the cougar and mountain lion, pumas can reach 8ft (2.4m) from nose to tail tip, run at 40mph (64kph) and leap up to 18ft (5.4m) in the air. They’re solitary predators, with a territory covering as much as 80 sq miles (129 sq km), and survive mainly on a diet of small mammals and their favourite prey, guanacos, although occasionally their fondness for sheep also brings them into conflict with Patagonia’s gauchos.

ORIENTATION

Start // Refugio del Paine

End // Refugio Las Torres

Distance // 44 miles (71km)

Getting there // Torres del Paine National Park is 70 miles (112km) northwest of Puerto Natales. Shuttle buses and private transfers can easily be arranged.

When to go // October to April.

Where to stay // Hotel Lago Grey (www.lagogrey.cl), Hotel Explora (www.explora.com).

More info // www.swoop-patagonia.com has guided hikes.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

PATAGONIAN EPICS

LAGUNA DE LOS TRES, LOS GLACIARES

Hikers visiting Torres del Paine often add on an expedition to the national park of Los Glaciares, which offers equally stunning scenery, not to mention a wealth of day hikes and multi-day treks. This 14-mile (22km) hike is one of the classics, carrying you deep into the mountains of the Fitz Roy range. The name – the Lagoon of Three – refers to the trio of mountains that lie in wait at the end of the trail: Cerro Fitz Roy, Aguja Poincenot and Torre, rising like rocky guardians around the lakeshore. It’s a long but rewarding day hike, with the added bonus that you get to sleep in a proper bed and get a good meal at the end of the day: the town of El Chaltén has plenty of accommodation options for hikers.

Start/End // El Chaltén

Distance // 14 miles (22km)

More info // www.losglaciares.com

© Oleg Senkov | Shutterstock

drinking in the awesome vista of the Fitz Roy mountains

HUEMUL CIRCUIT

This little-known backcountry route in Los Glaciares National Park is much, much quieter than many of Patagonia’s trails, but it’s for a reason. This is a challenging and technical trek that occasionally teeters over into scrambling and rock climbing; at certain points, you’ll also have to ford rivers, which can be a nerve-wracking proposition when they’re in spate. The reward? Hiking in the kind of solitude that’s almost impossible to find in the better-known parts of Patagonia – not to mention an unforgettable view across the Southern Patagonian Ice Field.

Start/End // El Chaltén

Distance // 37 miles (60km)

More info // www.losglaciares.com

DIENTES DE NAVARINO

If you really want remote, then this hike is the one to choose. It starts with a flight by prop plane from Punta Arenas to the southernmost town on earth, Puerto Williams, located on the Chilean island of Isla Navarino, before heading off into areas of the Patagonian Andes where few people, let alone hikers, ever tread. At 55°S, this is a hike that very nearly takes you off the bottom of the map as you go through the chain of spiky mountains that rise up from the middle of the island. At the hike’s summit, you’ll get stunning views over the Beagle Channel and, on a very clear day, all the way to the distant tip of Cape Horn.

Start/End // Puerto Williams

Distance // 23 miles (37km)

More info // www.swooppatagonia.com

© Olga Danylenko | Shutterstock

king cormorants gather in the remote Beagle Channel;

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

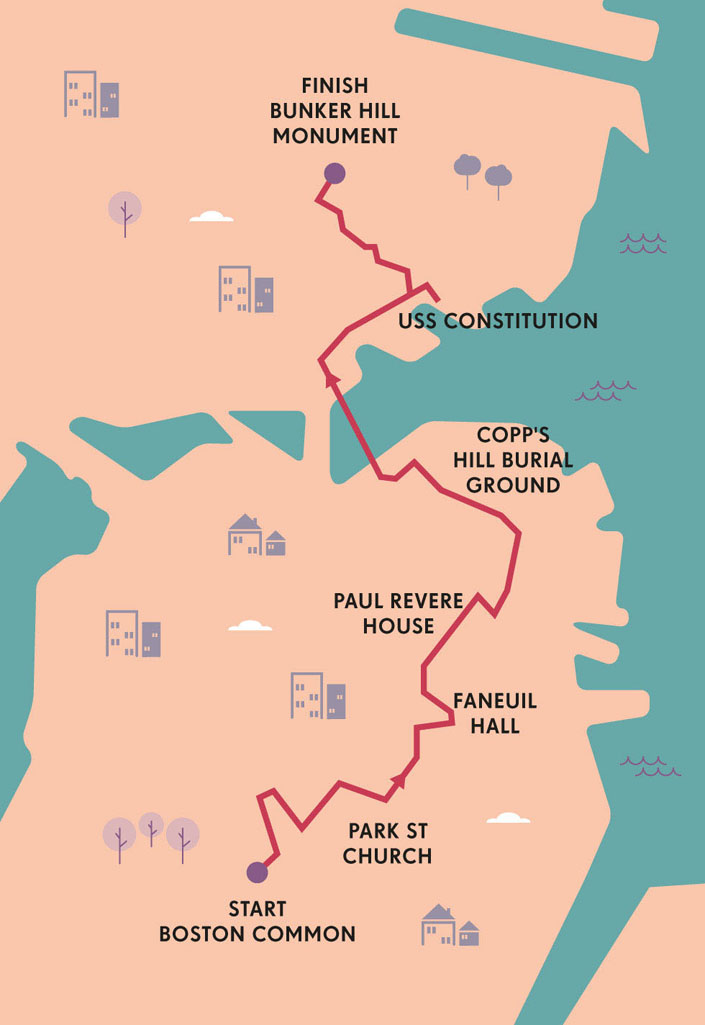

BOSTON’S FREEDOM TRAIL

Stroll through America’s revolutionary past on a historical hike visiting early settlers’ cemeteries, patriots’ meeting places and key sites in the struggle for independence.

At first glance, Boston Common doesn’t seem so remarkable. Sure, there’s a bandstand, and a pond, and on the balmy September morning of my visit the trees teased with glimpses of their flaming fall finery. But it’s much like any other city park, populated by ordinary folk strolling, lolling, or browsing a newspaper on a bench.

Except it’s not. This 50-acre (20-hectare) emerald swath is the oldest public park in the USA, established in 1634 by Puritan settlers. It’s witnessed the hangings of heretics and ‘witches’; it’s been trampled by redcoats; it’s hosted Judy Garland, Martin Luther King Jr, Pope John Paul II and Mikhail Gorbachev. And it’s the starting point for possibly America’s most intriguing urban hike: the Freedom Trail. This 2.5-mile (4km) route snakes between key historic sites, most relating to the 18th-century American struggle for independence. It’s also simply a fine walk – a great way to introduce yourself to the buzzing heart of Boston, bars and markets as well as churches and museums.

The first stop beckoned brightly just steps from the start point at Boston Common Visitor Center: the gilded dome of the Massachusetts State House. Twenty years after his famous nocturnal ride to Lexington, Paul Revere joined John Hancock in presiding at the laying of the building’s cornerstone, and went on to copper-plate its dome.

But though such monumental landmarks are impressive, more fascinating are the sites that speak of the day-to-day lives (and deaths) of early Bostonians. Following the line of red bricks embedded in the pavement, I ambled down Park St to its namesake church and the adjacent Granary Burial Ground, where I paid homage to pivotal patriots John Hancock, Samuel Adams and – there he was again – Paul Revere. Those patriots are the big draws, but I found the earliest gravestones, some decorated with winged skulls, more evocative still.

© Holbox | Shutterstock

cobblestoned Acorn St in the Beacon Hill district

Past King’s Chapel I wandered, saluting Benjamin Franklin en route down School St. His statue peers down from a pedestal near the site of the Boston Latin School, the country’s first public school, founded in 1635. Such education bore fruit among the 19th-century writers who congregated at the nearby Old Corner Bookstore, built around 1812 and now a Mexican restaurant. Here, poets and novelists including Longfellow, Hawthorne, Emerson and Beecher Stowe gathered; among the fried food and chillies, I hoped (but failed) to detect a whiff of literary genius still.

© PRILL | Shutterstock

anchored in Boston Harbor, the 18th-century USS Constitution

They say talk is cheap. Not so in pre-independence Boston: some of the most costly and influential was exchanged across Washington St at the Old South Meeting House. Unlike at the former bookstore, this red-brick church built in 1729 exudes an atmosphere of past activism. Here, in the late 1760s, mutinous mutterings against repressive British rule and taxation swelled to a roar, climaxing in the Boston Tea Party of 1773 in which hundreds of colonialists rushed from the meeting house to toss heavily taxed tea into the harbour.

Heading north up Washington St, I found myself engulfed by skyscrapers, beneath which cluster three of the most notable venues of independence action. The 1713 Old State House is hemmed in by high-rises but stands as proud as it did nearly 250 years ago, when the Declaration of Independence was read from its balcony in July 1776. That triumph was in marked contrast to the bloody clash that had erupted just outside it six years earlier. On 5 March 1770, a mob of aggressive Bostonians surrounded British soldiers, who fired into the crowd, killing five in what became known as the Boston Massacre. And steps away, Faneuil Hall hosted 1764 protests against the British sugar tax, meetings led by John Hancock discussing the tea taxation question, and a century later rallies against slavery addressed by the likes of Frederick Douglass.

“The 1713 Old State House stands as proud as it did when the Declaration of Independence was read from its balcony”

History makes me hungry. Fortunately, the central colonnade of Faneuil Marketplace behind the Hall is lined with tempting stalls peddling all manner of delectables; a hefty lobster roll later and I was fuelled for the second half of the trail.

Not that there’s any shortage of eating opportunities en route. Along Union St, the western edge of Blackstone Block – Boston’s oldest commercial district – the Union Oyster House has been dishing up seafood treats since 1826, in a shop built more than a century earlier. And on Hanover St, the main artery of the North End – Boston’s Little Italy – I watched pizza aficionados lining up on the pavement for the city’s finest slices and arancini; I joined the (just as lengthy) line across the road in Mike’s Pastry to choose from 18 flavours of cannoli, baked here for over 70 years.

© Joe Daniel Price | Getty

the historic Old State House.

With blood-sugar levels soaring, I delved into Paul Revere’s simple shingle-clad house, built in 1680 and bought by the famed silversmith and patriot 90 years later. Today it’s a true time machine, a treasure trove of period furnishings (even Revere’s wallpaper), giving a palpable sense of Boston life centuries ago.

Turning northwest on to his namesake mall, I was confronted with the spire of the Old North Church. I pictured its spindly tower in 1723, when it was first raised on a promontory at that time surrounded by the waters of the Charles River. And again on that night half a century later, when Revere’s two lanterns hung from the steeple alerted his patriot comrades in Charlestown of the British plans. I envisioned its view of the bloody battle at Bunker Hill across the river two months after Revere’s ride, and of ‘Old Ironside’ – USS Constitution – being constructed in Hartt’s shipyard nearby two decades later.

There, on the water’s edge, I ended my journey of the imagination, having covered just 2½ miles (4km), but over two- and-a-half centuries of drama. PB

BLACK HERITAGE TRAIL

Another fascinating route winds through the streets of Beacon Hill. The Black Heritage Trail (maah.org/trail.htm) links sites connected with the African-American community who settled here and in the North End. It includes the 1806 African Meeting House (the USA’s oldest surviving black church) and Abiel Smith School, founded in 1835 and now home of the Museum of African American History.

ORIENTATION

Start // Boston Common

End // Bunker Hill

Distance // 2.5 miles (4km)

Getting there // Park Street T (subway) station, at the junction of the Red and Green Lines, is close to the start of the trail at Boston Common Visitor Center (www.bostonusa.com/about-gbcvb/contact-us), which sells Freedom Trail guidebooks and maps. Buses 92 and 93 return downtown from near Bunker Hill. Boston’s Logan International Airport is connected with the city centre by Blue Line T, Silver Line bus and water shuttle. For public transport information visit www.mbta.com.

Tours // Walk into History tours led by guides in period costume run frequently year-round (http://thefreedomtrail.org/book-tour).

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

US URBAN HISTORICS

THE CONSTITUTIONAL, PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA

US capital for a decade before DC took up its duties in 1800, Philly is understandably proud of its role in the foundation of the nation. This self-guided tour snakes past more than 30 sites connected with the struggle for independence and the first years of the fledgling country. You’ll visit the Pennsylvania State House – now Independence Hall – where Thomas Jefferson’s pivotal document was adopted on 4 July 1776. You’ll admire the Liberty Bell, now famously cracked but which may have rung to announce the first reading of the Declaration. And you’ll see a wealth of firsts: the sites of the first US Capitol and Supreme Court, the First Bank of the United States, and the Betsy Ross House where that matron was reputedly commissioned to create the first American flag in 1877.

Start // National Constitution Center

End // African American Museum

Distance // 3.3 miles (5.3km)

More info // www.theconstitutional.com/tours

SAN ANTONIO RIVER WALK, TEXAS

Remember the Alamo? That fateful clash in 1836, at a former Spanish Catholic mission that had become a stronghold for Texan soldiers, is seared into the memories of all American schoolchildren. The remains of the battle-scarred monument now lie in downtown San Antonio, forming the centrepiece of a walk through the city’s most historic districts. An exemplar of urban riparian regeneration, the River Walk incorporates walking, cycling and boating trails tracing the San Antonio River from Brackenridge Park south through Downtown to Mission Espada. For a day of heritage hiking, begin at the Alamo, roam the two-centuries-old arts village La Villita, pause in the Plaza de las Islas and San Fernando Cathedral, founded by Canary Islanders in the 1730s, then stride south past old-time saloons to a cluster of Spanish missions.

Start // Brackenridge Park

End // Mission Espada

Distance // 15 miles (24km)

More info // visitsanantonio.com

BARBARY COAST TRAIL, SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

At the start of the 1840s, the city now called San Francisco was neither a city, nor called San Francisco (it was then Yerba Buena), nor in the United States. Yet just a decade later, within two years of the California gold-rush frenzy sparked in 1848, the population had boomed to more than 25,000. Follow the Barbary Coast Trail, waymarked with dozens of bronze medallions and arrows embedded in the pavement, to explore sites tracing the city’s history from the gold rush to the earthquake of 1906, including the Old Mint of 1874, the Pony Express Headquarters, the Wells Fargo Museum, the ships of the Maritime Historic Park, and reminders of waves of immigration from China, including the USA’s first Asian temple.

Start // Old Mint

End // Ghirardelli Sq

Distance // 3.8 miles (6km)

More info // www.barbarycoasttrail.org

© Erik Pronske | Getty

San Antonio’s San Fernando Cathedral, the oldest standing church building in Texas

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

ROCKIES ROAD: THE SKYLINE TRAIL

One of Canada’s backcountry classics, the Skyline is an unforgettable adventure straight through the heart of the Rocky Mountains.

Ared sky is rising over the Rockies as the shuttle bus pulls out of Jasper and rattles into the backcountry. The bus is rammed with hikers, chatting and double-checking their packs for supplies. Outside, pine forest blurs past the windows, and above the treeline, I catch glimpses of saw-tooth peaks, crests tinted pink by the morning sun. Everyone’s excited about the hike, but there’s a crackle of trepidation too: an adventure’s guaranteed, but no one’s sure quite what the mountains have in store.

© Josh McCulloch | Getty

Jasper mountain stream

Running for 27 miles (44km) between Maligne Lake and Maligne Canyon, the Skyline is considered the crème de la crème of Canadian hiking. It’s aptly named: over half the trail runs way above the treeline, a high-level, big-sky route offering some of the grandest views in the Rockies. Unfortunately, its altitude means it’s exposed to the weather, and its wildness means wildlife encounters are a constant possibility. Reflexively, I check my belt for my canister of bear spray as I step off the bus, bid farewell to the driver and take my first step on to the Skyline.

Most hikers cover the route in two or three days, staying at backcountry campgrounds dotted along the trail. I’ve been hiking in the Rockies for a few months, so I feel confident about tackling it in two – although looking up at the craggy peaks ahead, I wonder if I might have overestimated my abilities.

The first stretch, at least, is a gentle one. From the trailhead, the path winds through stands of tall pine and fir. After a few miles, the silvery pools of Lorraine Lake and Mona Lake appear, and I stop to pitch a stone across the still water before pressing on to Little Shovel Pass, where I’m treated to a postcard view over Maligne Lake and the Queen Elizabeth Range. I break for lunch, watching a family of hoary marmots play on the rocks, whistling and hooting softly to each other, their ears twitching and fur rippling in the breeze.

© All Canada Photos | Alamy

a marmot

Further up the mountain lies the sprawling meadow known as the Snowbowl. It’s late August now, and the meadow is laced with snowmelt pools, interspersed amongst a carpet of wildflowers and tundra. It feels thrillingly wild and empty, and I stop for a while to watch a hawk circling high above the mountaintops, scanning the valley below for unseen prey.

By the time I reach my overnight spot at Curator Campground, it’s early evening, and the sky’s the colour of candy floss. It’s not far from the famous Shovel Pass, named by plucky adventurer Mary Schaffer, who got stuck here in deep snow in 1911; she and her guide Jack Otto had to dig their way through using shovels fashioned from tree trunks. I find a patch of grass and pitch my tent, boiling some tea as I stretch out my sleeping bag and give my aching legs a rest. Soon enough, I get chatting to some other hikers, and we share hiking tales over a supper of camp-cooked chilli, followed by biscuits, chunks of dark chocolate and mugs of hot tea. Afternoon drifts into evening, evening into night; stars prick the darkening sky, and a chill descends over the valley. I head off to bed by the light of my head-torch, but not before I’ve strung up my food bag; I haven’t caught sight of any bears yet, but I know they’re out there, and tonight, I’m camping out in their backyard.

© Zhukova Valentyna | Shutterstock

Maligne Lake

I wake with the lark, muscles aching. Mist hangs on the meadow as I fry up a quick breakfast, then get an early start on the trail. Grey cloud squats on the mountains, and the wind is getting up, rattling through the trees and whipping up dust devils along the rocky trail. It gets fiercer as I climb to the trail’s highest point, the Notch, a rocky pass perched at 8235ft (2510m). The wind is howling over the mountain now, keening and whooshing across the rock face in great buffeting gusts. Grimly, I remember a ranger telling me that the Notch was the most dangerous section of the Skyline; the high-wire point, he called it. Several hikers have been struck by lightning here during storms. Still, I can’t help pausing to shoot the view – a widescreen panorama over the Athabasca valley, with the ghostly silhouette of Mt Robson looming on the horizon.

© Maciej Bledowski | Shutterstock

another dramatic Torres del Paine panorama

“Looking up at the craggy peaks ahead, I wonder if I might have overestimated my abilities”

MARMOT OR PIKA?

Once prized for their pelts, fuzzy mountain-dwelling marmots are a member of the squirrel family. They live in burrows in close-knit family groups; like meerkats, the family keeps watch for predators, and you’re bound to hear their distinctive hooting, whistling cries if you get too close. Pikas are much smaller, with round bodies and big ears that make them look rather like oversized mice – but they’re actually more closely related to rabbits.

© Mark C Stevens | Getty

the Skyline Trail

Then, as I trudge along the ridgeline of Amber Mountain, the wind suddenly drops, as though someone’s flicked the off switch. Stillness returns to the mountain, and buttery sunshine bathes the trail as it switchbacks down to Tekarra Lake. Pikas appear from their burrows, chirruping as they dart over the rocks. Above me, a line of bighorn sheep pick their way along a narrow precipice. Gradually, barren rock gives way to tundra, then to scrubby forest, and as I pass beneath the shadow of Excelsior Mountain, I know I’ve finally stepped off the high-wire on to safer ground.

From here, I’m on the home stretch, which is an old fire-road that leads down into Maligne Canyon, but there’s time for a stop at the lookout on Signal Mountain for one last panorama. Ragged peaks zig-zag along the horizon, crusted with glaciers fed by the great Columbia Icefield, and the blue thread of the Athabasca River snakes along the valley floor. But I don’t have very long to enjoy the view; ink-black clouds are massing overhead, and as I trudge down the fire-road, a boom of thunder cracks over the valley like cannon fire.

By the time I make it to the trailhead and the shelter of the shuttle bus, rain is hammering against the windshield, and I’m soaked to the skin. But I don’t mind. A cold beer is waiting for me in Jasper Town, and I feel like I’ve earned it. OB

ORIENTATION

Start // Maligne Lake

End // Maligne Canyon

Distance // 27 miles (44km)

Getting there // Edmonton is the nearest international airport, some 225 miles (362km) east of Jasper. The Maligne Lake shuttle runs to the trailhead from Jasper Town.

When to go // Late July to late September.

Where to stay // There are campgrounds at Evelyn Creek, Little Shovel, Snowbowl, Curator, Tekarra and Signal. Bookings are mandatory in summer, as is a valid Backcountry Pass.

What to take // Bear spray, plasters, wet-weather gear.

More info // Jasper Park Information Centre (www.jasper.travel), Parks Canada (pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/jasper).

Things to know // All the Skyline’s campgrounds are equipped with barrel toilets and bear poles for food storage. Campfires are sometimes allowed when the fire risk is low, but gas stoves are cleaner and more efficient.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

GREAT CANADIAN HIKES

WEST COAST TRAIL, VANCOUVER ISLAND

Constructed in 1907 as a means of rescuing sailors shipwrecked along the Vancouver Island’s rocky, reef-lined coast, this 47-mile (75km) trail has become one of Canada’s most popular hiking trails. Part of the Pacific Rim National Park, it provides a fabulous introduction to the island’s natural environment, traversing old-growth forest, wild beaches, muddy bogs and tumbling waterfalls. Ladders, boardwalks and stone staircases all form part of the route, and there are several sections where you can choose to veer up into the highlands or stick close to the pebbly, sea-washed shore. Much of the time, you’re walking on ancient paths first trodden by First Nations people some 4000 years ago, and the land here remains sacred to native tribes – so this is definitely a trail to tread with reverence. Most people take five or six days to complete it.

Start // Pachena Bay

End // Gordon River

Distance // 47 miles (75km)

More info // www.westcoasttrail.com

© Westend61 Premium | Shutterstock

negotiating a footbridge through the West Coast Trail

THE FUNDY FOOTPATH, NEW BRUNSWICK

Well off the beaten track on Canada’s under-appreciated east coast, this seaside trail explores the wild, unspoilt stretch of coastline between Labrador and Florida, one of the last untouched areas of true coastal wilderness left in North America. Running for 25 miles (41km) around the Bay of Fundy, it’s a wonderful wild hike that gives access to dramatic cliffs, tumbling cascades, pristine rivers and countless hidden sandy beaches where you’re unlikely to spot another soul. Unsurprisingly, the cliffs here are a haven for all kinds of seabirds, and if you’re really lucky, you might even spy a pod of dolphins or right whales playing in one of the numerous isolated coves. But it’s the tides here that provide the real challenge: they’re some of the highest on earth, and several sections of the trail are cut off by rising water. Along with a good map, a tide timetable is a must-have accessory.

Start // Big Salmon River

End // Fundy National Park

Distance // 25 miles (41km)

More info // www.fundyhikingtrails.com

© Justin Foulkes | Lonely Planet

Hopewell Rocks in the Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick

THE GREAT DIVIDE TRAIL, BRITISH COLUMBIA/ALBERTA

This is it: the big kahuna, the granddaddy, the trail to end all trails. Sprawling for a truly epic 745 miles (1200km) along the borders of British Columbia and Alberta, this long-distance route traces the course of the so-called Great Divide – the continental ridge that separates North America’s west and east. To the west of the trail, all rainfall runs into the Pacific Ocean; to the east, it trickles down to the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico. The trail zig-zags across the divide numerous times, traversing areas of wilderness that have only recently been opened up to hikers. This is the big-sky Canada you’ve been dreaming of, complete with all the wild critters you’d expect to encounter – including moose, wolves, black bears, grizzlies and, unfortunately, hordes of biting insects in summer. The reward? Canada’s most challenging hike, bar none.

Start // Waterton

End // Mt Robson

Distance // 745 miles (1200km)

More info // www.greatdividetrail.com

© Patricia Davis | Getty

just your regular Vermont inhabitant: a young moose

© Radius Images | Alamy

black bears are frequently spotted in BC

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

CONCEPCIÓN VOLCANO HIKE

Wake before dawn in Nicaragua to summit the sheer slopes of this active volcano, climbing through field and forest all the way to the steam-shrouded crater.

It is dawn, and I’m nervous. ‘Just how active is “active”?’ I ask the guide. ‘Don’t worry, we always check the seismic forecast before we leave,’ he assures me.

There are certain things you want to know before summiting a 5282ft (1610m) live volcano. I’m on the island of Ometepe in the middle of vast Lake Nicaragua. The island is shaped like a figure of eight lying in the water, each side a volcano. On the southeast side there’s Maderas, its slopes covered in cloud forest. Its last known eruption was in the Pleistocene epoch. Concepción, the one I’m hiking up today, last erupted a bit more recently. Like, 2010 recently. It was no big deal, though, the hotel owner tells me. Just a big ash cloud.

© Michael Dwyer | Alamy

white-throated magpie jays on Ometepe Island

Oh, OK then.

Seen from the distance, Concepción looks like a child’s drawing of a volcano: a perfectly symmetrical cone with a flat top haloed by clouds. Many consider reaching its summit to be the most difficult hike in all of Nicaragua, no small thing in a nation with several major mountain ranges and 40-odd volcanoes. This isn’t my first Nicaraguan volcano hike, but it will definitely be the longest. We’re aiming to get up and back within eight hours, though it can take 10 or more.

© Christa Brunt | Getty

cloud shrouds Concepción volcano

Rising in the bluish predawn, we begin our summit assault in the tiny hamlet of La Concepción. We walk through fields of coffee and banana plantations, nodding greetings at several early-rising farmers. But the easy stroll gets challenging very quickly, as the trail takes a steep turn up the slope and into the forest. This is dry tropical forest, dense with vines and ferns. It’s still early, and the first weak rays of sunlight barely penetrate the canopy. Howler monkeys screech overhead, an eerie sound that reminds me of the spooky stories I heard from the proprietor of the hotel where we stayed the night before, stories of a man-devil named Chico Largo who roams the nature reserve south of Concepción, turning men into cows and worse. We climb and climb, sometimes walking up stairs hacked by machete out of the earth. They’re slippery beneath our feet, still wet with morning dew. I trip on a root and nearly land face first in the mud.

© Simon Dannhauer | Shutterstock

a female howler monkey

Finally we come to El Floral, a lookout point at about 3280ft (1000m). In the morning light we can see down across the treetops to the patchwork fields below and all the way across the navy waters of Lake Nicaragua to the mainland. On some days you can actually see the Pacific Ocean, our guide tells us, but today is a little hazy. We crouch and eat our sandwiches of avocado and salty farmer’s cheese, then share a ripe, sweet local mango. Fortified, we push on.

© Riderfoot | Shutterstock

the full volcanic vista

From here on, the path becomes very exposed, rocky and unnervingly steep. The forest has dropped away and we find ourselves climbing through alpine meadows of low, spiky shrubs. Soon, the shrubs are replaced with grass, which becomes shorter and shorter before petering away entirely. We’re now walking on volcanic scree, the slope strewn with boulders the size of beach balls. Our feet slip on the loose grit, and at times I find myself on all fours, like a very awkward mountain goat. It’s also chilly, with a raw wind whipping up the dust. I’m glad I brought a windbreaker. We ascend like this for what feels like ages, no longer bothering to speak because of exhaustion and the noise of the wind. The smells – sulphur, and something even more harsh – grow stronger.

Slowly, then all at once, we are enveloped in cloud. But it’s not ordinary cloud. This is cloud mixed with volcanic steam emanating from deep inside the mountain, acrid and yellowy. Visibility turns to nearly nothing. Our guide is only a few feet ahead of us, but at times I can only see his shoes or his swinging arms. The smell is overwhelming, rotten eggs and sharp metal odours. You can understand why ancient peoples from many cultures described this as the stench of hell.

“We’re at the edge of the crater. This must be what it’s like to visit Mars”

Then our guide turns and stops. We’re at the edge of the crater, he tells us. It’s so cloudy we wouldn’t have known. We snap a few pictures of ourselves, though we won’t be able to see much. I become aware of a warm wind, which I realise is heat coming from the nearby fumaroles, those rents in the earth leading deep inside the volcano. This must be what it’s like to visit Mars.

Not everyone who summits Concepción has this steam and cloud and sulphur experience. Some days the volcano is quieter and wind patterns mean there’s little or no cloud on top. On those days you can see for hundreds of miles across lake and land and ocean. But I’m glad to experience this, this strange grey hellscape.

Now all we need to do is get back down. As every mountain climber knows, descent is often the most dangerous part of the climb. This is especially true when the descent is down hundreds of yards of volcanic boulders and grit with the wind blowing in your eyes. But we catch a lucky break as we reach the relatively safety of the high meadows. The clouds dissipate, opening up a view over the patchwork of farmland spreading out below. We still can’t quite see the ocean, but the shining waters of Lake Nicaragua look pretty darn glorious.

Exhausted, bug-bitten and muddy, we stumble back to our hotel. Time for a shower, a huge plate of gallo pinto (beans and rice), and a dreamless sleep in the shadow of the volcano. EM

OMETEPE’S DIVERSITY

Inhabited since 2000 BC, Ometepe Island’s earliest peoples left behind thousands of petroglyphs, pottery shards and stone idols. Today, its residents farm coffee, plantains and cacao in the rich volcanic soil. The forests are home to howler monkeys, armadillos, sloths and 80 types of migratory birds. One variety of tree and a type of salamander occur nowhere else but Ometepe.

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Concepción village

Distance // 9 miles (14km)

Getting there // Nicaragua’s main airport is in Managua. From here, reach Ometepe by ferry from the lakeside town of San Jorge. Moyogalpa is the main town on Ometepe, so most hikers stay here the night before their climb.

When to go // The December-to-March dry season is best for clear summit views, while September to November can be so rainy it’s dangerous to go past the lookout point.

What to take // Plenty of water, snacks and sunscreen, and a windbreaker for the summit.

Things to know // Two trails up the volcano start from villages near Moyogalpa, and another from La Sabana, east of the volcano. Start as early as 4am as the afternoon often brings bad weather. Guides are mandatory.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

VOLCANO HIKES

VESUVIUS’ CRATER, ITALY

Although the climb up Vesuvius is the busiest, most commercialised hike in Italy, the magnitude of what you witness makes up for the aggregation of panting, sweating, flip-flop-wearing humanity. Most of these won’t have realised that they are required to leave their vehicles at the Quota 1000 car park, 922ft (281m) below Vesuvius’ modern summit, necessitating a 2822ft (860m) steep and stony scramble to the rim of the gaping crater. From the car park, the trail rises in a southwesterly direction, switching back after a couple of hundred metres then climbing steadily at an average gradient of 14 percent towards the crater. Remember that Vesuvius will erupt again sooner or later, so you climb it at your own risk. Be aware, too, of vipers – and illegal taxi drivers…

Start/End // Quota 1000 car park

Distance // 1.9 miles (3km)

VOLCÁN LANÍN, ARGENTINA

Towering over the northern Lakes District, Volcán Lanín rises from a base plain of around 3609ft (1100m) to a height of 12,388ft (3776m). Its thick cap of heavily crevassed glacial ice makes it look almost impossible to climb, but up its eastern side is a strenuous, though straightforward, ascent. In fact, Lanín is probably the highest summit in Patagonia safely attainable without ropes. An ice axe and crampons are mandatory, however, as are suitable mountain clothing and kit. The summit is normally tackled between November and February and an early start is imperative, since after midday the snow often becomes soft and slushy, making the going tiring. The volcano’s steep slopes are no place for tents, so trekkers must stay at one of three unstaffed refugios, roughly halfway up the mountain. We suggest the rustic, tin-roofed Refugio CAJA at 8727ft (2660m) for the end of both your first day’s ascent and the following night on the way back down.

Start/End // Guarderia Tromen

Distance // 15 miles (25km)

MT WASHBURN AND SEVENMILE HOLE, YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK, USA

This long day or overnight shuttle hike climbs 1400ft (425m) from Dunraven Pass to the summit of 10,243ft (3122m) Mt Washburn, all that remains of a volcano explosion some 600,000 years ago that formed the vast Yellowstone Caldera. From the small car park at Dunraven Pass, a wide trail grants a comfortable but steady sidling ascent through forests of subalpine fir. Broad switchbacks and a narrow ridge lead to Mt Washburn’s lookout tower, which affords majestic views across the Yellowstone basin. The trail then drops southeast towards undulating wildflower meadows and campsite 4E1, about 90 minutes from the top. You’ll continue southwest through boggy grassland and the boiling mud pools at Washburn Hot Springs. From the southern rim of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, which plunges some 1312ft-deep (400m), the views become ever more spectacular en route to the Glacial Boulder Trailhead. Bear in mind that this is grizzly country, and bears are populous here in late summer and early autumn.

Start // Dunraven Pass

End // Canyon

Distance // 16.6 miles (26.7k)

© Pete Seaward | Lonely Planet

steam escapes from thermal springs in Yellowstone National Park

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

BORDER PATROL ON THE PACIFIC CREST TRAIL

Bursting with US mountain panoramas and challenging backcountry terrain, this cross-country corridor is perfect for anything from a weekend escape to an epic five-month adventure.

It is late April, and dawn is breaking over the southern Californian desert as the dust kicked up by my friend’s car settles. I watch as she disappears into the distance, then turn around and approach a large wooden marker standing a few feet from the US/Mexico border fence. It reads ‘Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail; Southern Terminus; Mexico to Canada 2650 Miles’. A dirt footpath meanders away from the site. I snap a picture, hoist my backpack on to my shoulders, mutter something reassuring and take my first few steps along the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) towards Canada.

The PCT truly is epic, traversing the country’s wilderness virtually unbroken between Mexico and Canada. It cuts the states of California, Oregon and Washington in half by following the spines of the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountain ranges, passing through 25 national forests, seven national parks and climbing over 90 vertical miles along the way. And I’m attempting a hike of its 2650 miles (4265km) in a single season, a feat commonly referred to as a ‘thru-hike’ and usually met with some combination of confusion, awe and bewilderment when announced to the general public.

Timing is key: a late-April start will get me through the desert before it becomes too hot and dry, let me reach the Sierra Nevada mountains just as the snow from the previous winter has melted, and then give me three quick months to make it through Oregon and Washington to Canada before winter.

© Min Chiu | Shutterstock

tackling the trail through Oregon

The first section of the PCT is known as ‘the Desert’, though that betrays the astonishing diversity of landscapes it passes through. From the barren hills near Mojave to the dense pine forests surrounding Big Bear Lake, this section is all about variety. The desert is also a refreshing social experience, with dozens of hopeful hikers starting northbound from the border each day in April (more than 90% of hikers walk northbound). Many lifelong friendships are forged in these first 700 miles (1126km).

© Lars Schneider | Getty

Rainbow Falls in California’s Mammoth Lakes

The popularity of the PCT has skyrocketed over the past decade, largely due to the movie adaptation of Cheryl Strayed’s best-selling 2012 novel Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail. In two decades numbers have grown from a couple of hundred intrepid hikers annually to more than 3000 in 2016, which can be a mixed blessing; it makes it easy to find a group to hike with, but those seeking solitude may want to consider a southbound hike starting at the Canadian border instead.

A month after leaving the southern terminus I arrive at the outpost of Kennedy Meadows, which marks the end of the desert. By now I’ve got my ‘trail legs’. I can walk 25 miles day after day with a full pack without a problem, my feet have callused up and resemble a hobbit’s leathery soles, and my constant caloric deficit means I’ll devour anything I can get my hands on. The High Sierra awaits. Stretching nearly the entire length of California, the Sierras are a section of outstanding natural beauty and spirit-testing isolation. Containing 10 snow-veiled passes above 10,000ft (3048m), countless river crossings and minimal resupply or evacuation routes, it’s a landscape that demands respect and in return delivers some of the most dramatic hiking anywhere on the planet. Translucent mountain lakes, sheer granite cliffs and raging rivers teeming with fish are just some of the remarkable vistas the trail traverses for 600 miles (965km) between Kennedy Meadows and Lassen Volcanic National Park in northern California.

© Kojihirano | Getty

California’s Lassen Volcanic National Park is one of seven on the Pacific Crest Trail

“Stretching nearly the entire length of California, the Sierras provide a section of outstanding natural beauty”

North of Lassen the landscape undergoes a geological shift as the granite peaks of the Sierras fade into the distance and give way to the volcanoes of the Cascade Range. Dotting the landscape like breadcrumbs from northern California all the way through Washington, these behemoths dominate my views for the next 1000 miles (1609km). The frequent ascents/descents of the Sierras are replaced by the mellow rolling hills and forests of Oregon as the PCT crosses ancient lava fields and passes close to each of the Cascade volcanoes. A highlight of Oregon is hiker-friendly Timberline Lodge on the flanks of Mt Hood, famous for a breakfast buffet that puts even the most voracious hiker’s appetite to the test.

© Patrick Poendl | Shutterstock

marking the route

With Oregon behind me, I descend towards the Columbia River and savour the crossing into Washington, the final state of my journey. Here Oregon’s forgiving terrain comes to an abrupt end and almost instantly I’m climbing up and down the deep glacial valleys of the northern Cascades. Three weeks after crossing the Columbia I’ve reached Stehekin, the final town on the trail and possibly the most charming. Sitting on the northernmost coast of a large mountain lake, it can only be reached by foot, boat or seaplane, an isolation that give it a uniquely laidback feel. The people are friendly, and relaxing days of soaking in the magnitude of my journey come easy.

After leaving Stehekin, I savour the three-day hike to the Canadian border and use the time to reflect on how lucky I’ve been to spend my summer experiencing all the ups and downs of the PCT – both physically and mentally. As a Canadian, part of what kept me going was a sense of walking home, though after months on the PCT the concept of ‘home’ had become a bit abstract. I eventually arrive at the northern terminus on a late afternoon in mid-August and am greeted by a monument that is near-identical to the one I left behind at the Mexican border. It reads ‘Canada to Mexico 2650 Miles’. This time I’ll go home instead, wherever that is. AB

KIND HEARTS AND CORONAS

A cooler in the middle of the desert stocked with beer, soda, and chocolate? It’s not a mirage, it’s ‘trail magic’! Along its entire length, the PCT has a vibrant local community of ‘trail angels’ who selflessly give their time and resources to help hikers on their journeys. Whether it’s a cold drink or a ride into town, their generosity is unparalleled and can turn a bad day into something magical.

ORIENTATION

Start // Southern Terminus: Campo, CA, USA

End // Northern Terminus: Manning Park, BC, Canada

Distance // 2650 miles (4265km)

Getting there // San Diego is the closest airport to the southern terminus, Vancouver to the northern.

When to go (earliest recommended start dates) // Northbound, 15 April; southbound, 1 July

What to take // Overnight backpacking gear; sleeping bag rated to at least -10°C (14°F); ice axe and crampons if in the Sierras or Washington before July; extra sun protection and water in the desert.

Maps and apps // Maps from www.pctmap.net and apps Halfmile’s PCT and Guthook’s Pacific Crest Trail Guide.

More info // Pacific Crest Trail Association: www.pcta.org

Things to know // Download a report providing near real-time status of water sources in the desert at pctwater.com.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

US SCENIC TRAILS

ICE AGE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL, WISCONSIN

Take a hike 15,000 years back in time, to when mammoths last wandered the earth. During the last ice age and North America’s most recent glacial period (known as the Wisconsin glaciation), a frosty crust lay over vast swaths of the USA, leaving impressive marks on the land, from rippling hills to gouged-out river valleys and dramatic ridges. Wisconsin’s Ice Age National Scenic Trail, which skirts the edges of North America’s last continental glacier, is like walking through a 3-D geography lesson, with added birdsong, fresh air and a sense of freedom. Only around half of the proposed 1200-mile (1930km) trail is currently complete, but it’s still possible to walk day-long or multi-day segments, or even the whole trail: the finished off-road sections range from 2 miles (3km) to 40 miles (65km) and are linked by temporary routes along quiet country roads.

Start/End // Interstate State Park/Potawatomi State Park

Distance // 1200 miles (1930km)

FLORIDA NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL, FLORIDA

Explore the alternative Sunshine State – that is, its estimable wild side, far from fairytale castles or talking mice… The Florida National Scenic Trail trail (which is around three-quarters complete) begins in the Panhandle, on the crunchy-white, turquoise-lapped beaches of the Gulf Islands National Seashore near Pensacola. From here it wiggles east and south, via salt marshes, crystal-clear springs, lakes, prairies, old-growth forests and historic urban areas. It finishes in Big Cypress National Preserve, bordering the Everglades, amid a lush swampland of bright bromeliads and giant ferns. This semi-tropical state is incredibly bio-diverse, and most of the trail is also a wildlife corridor, protecting both common and rare species. Possible sightings include black bear, deer, otters, alligators, gopher tortoises and sea turtles, plus a plethora of birds – the crested caracara and red-cockaded woodpecker are particularly sought-after species.

Start/End // Big Cypress National Preserve/Fort Pickens, Gulf Islands National Seashore

Distance // 1300 miles (2090km)

© Ken L Howard | Alamy

Florida’s lush Big Cypress National Preserve

POTOMAC HERITAGE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL, VIRGINIA, MARYLAND, PENNSYLVANIA AND DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Linking the Potomac and upper Youghiogheny river basins, this scenic trail isn’t one continuous walking route but a network of heritage, cultural and get-out-in-nature pathways across the region. Thus, thru-hiking isn’t the point here. Better to pick a part that sounds intriguing. For instance, those short on time could try Virginia’s history-laced Mt Vernon Trail, which runs for 17 miles (27km) along the Potomac from Theodore Roosevelt Island to George Washington’s home at Mt Vernon, via memorials, a 19th-century lighthouse, the old trading town of Alexandria and marshes prolific with birds. Multi-dayers might like the 150-mile (241km) Great Allegheny Passage or GAP, a hiker-biker route throughout parts of the Appalachian Mountains, linking Cumberland (Maryland) and downtown Pittsburgh using defunct corridors of the USA’s old railroads; this includes traversing cast-iron truss bridges, lofty viaducts and the 1968ft (600m) tunnel under Big Savage Mountain.

Start/End // Various, between Pittsburgh and the mouth of the Potomac River

Distance // 708 miles (1140km)

© Jeff Greenberg | Robert Harding

re-enacting a bygone age at George Washington’s home at Mt Vernon;

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

HELI-HIKING IN THE BUGABOO MOUNTAINS

To elevate your hiking to a totally epic level, fly by helicopter to remote trailheads among Western Canada’s mountains, glaciers and blue-green lakes.

The helicopter’s rotors whirl and roar above us, a dozen hikers squatting together, our heads low to the dirt. It’s the first day of our heli-hiking trip in British Columbia’s Bugaboo Mountains, and we’re learning to do the ‘heli huddle’. To stay out of the helicopter’s landing path, we crouch and cluster on cue, attempting to shield ourselves from the swirling propeller’s knock-you-over winds.

Heli-hiking is the warm-weather equivalent of heli-skiing, where a helicopter whisks you into the mountains in search of pristine terrain. But instead of seeking to make first tracks in untouched powder, you’re looking for remote hiking routes that are difficult or impossible to reach unless you fly in.

© Roy LANGSTAFF | Alamy

the helicopter prepares to ferry a new group of heli-hikers

Canadian Mountain Holidays (CMH), a tour company that pioneered heli-skiing back in the 1960s, now runs summer hiking adventures as well. Forty of us are headed for three days of hiking, based at the CMH Bugaboo Lodge on the edge of Bugaboo Provincial Park, a vast wilderness covering 33,700 acres (13,600 hectares) named for the Bugaboo Spire, one of several glacier-carved granite spikes that jut towards the sky.

For our first flight, a 10-minute hop from the helipad outside Kootenay National Park, the red-and-white Bell 212 helicopter shuttles us in small groups, flying low over the green hills. We land in a gravel field in front of the wood-and-stone lodge building.

I can’t help but say ‘wow’ as I walk into the lodge and look through the windows framing the view: the snow-topped Bugaboo Spire, more than 10,500ft (3200m) tall, with a carpet of evergreens beneath it and several peaks nearby.

In the equipment room, we meet several of the guides who’ll be accompanying us out on the trails. They chat with us while we try on boots, rain jackets and daypacks (you can bring your own or borrow from the CMH supply), to assess our hiking experience and comfort with different types of terrain. They weigh us – for helicopter load balancing – and by the time we go into the dining room for lunch, they have sorted us into groups of eight to 10 like-minded hikers.

After we eat, each group climbs into the helicopter in turn, for our first adventures on the trail. Even though it’s the middle of July, the height of Canada’s summer, the skies are overcast, and when the helicopter deposits us above a jade-coloured lake, we layer fleece sweaters under our jackets. Our guide, Paul, who tells us he’s been guiding for more than two decades, is very visible in his bright red parka. We follow him along a shale-covered trail that descends into a valley and climbs gently up towards the snow-capped mountains.

© Ken L Howard | Alamy

backcountry skiers on Bugaboo Glacier

As we hike higher on the ridge and across a field of snow, the clouds drop like a curtain around us, until it feels as if we could reach up and hold the heavy grey mist. The wind comes up, too, and we pause to pull on hats and gloves. We walk a little further, before Paul turns his face to the wind and scans the sky. He tells us it’s time to get off this ridge before the weather worsens. He radios for the helicopter, and after we snap a few quick photos with our feet in the summer snow, we hike down to a more sheltered spot, where the craft can land. When we pull up into the clouds, fat raindrops begin splattering the windshield.

We’re back at the lodge in time for ‘tea goodies’, when everyone gathers in the lounge (or hot tub) for cocktails and snacks, swapping stories about their day’s adventures. Dinner is served family-style, and we dig into Caesar salads, baked salmon and lemon tarts.

The next morning, the sun peeks through the clouds during my pre-breakfast stroll outside the lodge. White and yellow wildflowers surround a nearby pond, a perfect foreground for photos of the pointed peaks. One group sets off early, boarding the helicopter to tackle a via ferrata, a climbing route with iron rings fixed into the rock. I opt for ‘regular’ hiking, and the helicopter zips our group to a ridge, where we set out for a lagoon at the base of the Vowell Glacier. In less than an hour, we reach the blue-green pool below the glacier-topped mountains. Right on schedule, the clouds lift, and the sun glimmers off the water.

© Atlantide Phototravel | Getty

a precipitous via ferrata in the Bugaboo

“The helicopter whisks you into the mountains, looking for remote hiking routes difficult to reach unless you fly in”

TACKLING THE BUGABOOS

The spiky peaks known as the Bugaboos are in the Purcell mountain range, near the provincial border between British Columbia and Alberta, west of the Canadian Rockies. Since the early 1900s, these spires have drawn mountaineers who attempt to summit their rocky faces. Austrian-born Conrad Kain became a Bugaboos legend after he climbed both the Bugaboo Spire and the nearby North Howser tower in 1916. A remote mountain hut today bears Kain’s name.

scaling sheer rock walls

The helicopter returns and flies us to Tamarack Glen, where evergreens frame snowy granite hills. We have a picnic lunch overlooking another jade lake. Next, we fly around to the opposite side of the spires, landing on a rock outcropping with an expansive vista across a green valley and an up-close view of the spires. We hike through a meadow, across several small rushing streams and over rock slabs to an alpine lake.

Paul yanks off his boots and wades in to the lake. ‘It feels great’, he insists. I cautiously dip my toes into the icy water, and after the initial shock – yikes, it’s absolutely freezing! – it does rather perk up my flagging feet.

We trek over another crest, and Paul radios the helicopter. As it hovers above our hikers’ huddle, I’m stunned to see that the pilot can land on a flat rock not much larger than a queen-size bed.

The chopper flies us over to one more trail, where we hike amid evergreens and across several snowfields. The terrain is gentler here, but that’s OK with us. We’ve been out all day between the turquoise lakes, mountaintop glaciers and the spiky Bugaboo Spires. And with our helicopter to shuttle us from trail to trail among these remote Canadian mountains, we haven’t seen another soul. CH

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Canadian Mountain Holidays (CMH) Bugaboos trips start in Banff or Lake Louise, Alberta, or in Golden, British Columbia.

Distance // Varies

Getting there // Calgary (Alberta) is the closest international airport. CMH staff can help arrange transportation to the trip starting point. They’ll take you by coach to the helipad.

When to go // July, August, early September.

Where to stay // The comfortable 32-room CMH Bugaboo Lodge has an outdoor hot tub, indoor climbing wall and spectacular mountain views.

What to take // Prepare for variable mountain weather, from summer sunshine to whipping winds, rain, even snow. Layers are your friends. CMH stocks hiking boots, rain jackets, daypacks and hiking poles for guests to borrow if you’re travelling light or don’t have the gear you need.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

HELI-HIKING AROUND THE WORLD

CANADA

Several heli-hiking operators offer trips in British Columbia, Canada’s westernmost province. In addition to the Bugaboos trip, Canadian Mountain Holidays (CMH) runs heli-hiking adventures in two other BC destinations. Multiday trips based at its 26-room Bobbie Burns Lodge, north of Bugaboos Provincial Park, give guests the option to trek near the Conrad Glacier or tackle North America’s longest via ferrata. The newest CMH trip, from the 28-room Cariboo Lodge, takes hikers into the more remote Cariboo Mountains, west of Jasper National Park. If you don’t want to commit to a multiday heli-hiking trip, try out the sport in Whistler, a two-hour drive from Vancouver. Though this mountain community is best known for its skiing and snowboarding, it’s a year-round destination for outdoor adventures, including Blackcomb Helicopters’ half- and full-day heli-hiking excursions. For more heli-hiking options, contact Glacier Helicopters or Heli Canada Adventures, both based in the town of Revelstoke, in eastern BC’s Selkirk and Monashee Mountains.

More info // www.canadianmountainholidays.com; blackcombhelicopters.com: www.glacierhelicopters.ca; helicanada.com

CHILE

While the Chilean Andes have become a centre for winter heli-skiing, heli-hiking in this South American adventure destination is still in its infancy. But if the idea of heli-hiking in the world’s longest mountain range makes your heart beat faster, here are a couple of operators in Chile who organise helicopter-based hiking experiences. Lodge Andino el Ingenio, a small adventure lodge 40 miles (65km) southeast of Santiago, offers guests an optional day of heli-hiking. A 15-minute flight takes you into the Piuquenes Valley, where you’ll hike up for views of turquoise lagoons and the towering Andes. Located in the Andes, 95 miles (150km) southeast of Chile’s capital, between Río Los Cipreses National Reserve and the Argentine border, Noi Puma Lodge enables its guests to heli-hike into the nearby mountains. These day treks reward with vistas across valleys, glaciers and snow-topped volcanoes.

More info // www.lodgeandino.com; www.noihotels.com

NEW ZEALAND

In New Zealand, heli-hikers head for the South Island, particularly the region around the Aoraki/Mt Cook and Westland Tai Poutini National Parks in the Southern Alps, where a helicopter can fly you in to trek on massive glaciers and snowfields. Both Southern Alps Guiding and the Helicopter Line run heli-hiking trips to the country’s longest glacier, the Tasman Glacier in Aoraki/Mt Cook, which extends more than 15 miles (24km). These half-day excursions combine a helicopter flight with trekking on the glacier. The Helicopter Line also takes heli-hikers out to the Franz Josef Glacier, a 7.5-mile (12km) span of ice. On these half-day trips, you’ll fly over the glacier and then take a guided hike through dramatic glacial ice formations.

More info // www.mtcook.com: www.helicopter.co.nz

© Danita Delimont | Getty

heli-hikers land on the Franz Josef Glacier, New Zealand

a group sets off to explore the icy expanse on the South Island

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

CHOQUEQUIRAO: THE CROWD-FREE INCA TRAIL

Some 500 people hike the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu daily, yet a smaller path nearby leads to an even larger ‘lost city’ of Peru that remains remarkably untouched.

Rambling along the bumpy road from Cuzco out to Cachora, it becomes abundantly clear that I’ve left the feverish Machu Picchu crowds behind and am now entering the less polished corners of the Peruvian Andes. These are the fabled hills of the Inca, though they’re not the ones most visitors fly across oceans to see.

There’s only one reason travellers go out of their way to visit the rural village of Cachora, and it’s to see a set of ruins that lie just out of sight at the far end of the Apurímac Valley: Choquequirao. Said to be up to three times the size of the more widely known Machu Picchu, these ruins astoundingly see only about two dozen visitors each day.

I’ve always wondered what it must have been like to visit Angkor Wat, Chichén Itzá or Machu Picchu before the roads and tour buses arrived. Then I found out about Choquequirao, a citadel so far up in the Andes of Peru that archaeologists have only freed about 30% of it from the jungle.

© Christian Declercq | Shutterstock

Choquequirao on its lofty perch in the Andes

Before American explorer Hiram Bingham ever laid eyes on Machu Picchu, he was whacking his way through the Apurímac Valley, surveying the remarkable carcass of its so-called sister city. Scared off by the prospect of a gruelling, four-day round-trip journey, however, few tourists have bothered to visit over the years. I set off on my own journey to the ruins with a muleteer in tow. There are 28 miles (45km) ahead of me before I’ll see Cachora again, so it’s a relief knowing I won’t have to carry my pack, food and camping gear the entire way.

.jpg)

© Alex Robinson | Getty

on the trail to Choquequirao

Cachora lies in a bowl of terraced farmland, so my first objective is to climb out. I spend the remainder of the first day descending 4920ft (1500m) into the Apurímac Valley, walking ever closer to the orange-brown waters of its namesake river. I camp at Playa Rosalina, along the Apurímac River’s windy edge, and wake up early the following morning to cross over to the sun-baked side of the valley. It’s here that I’ll begin my ascent to the base of the ruins high up in the clouds at 10,000ft (3050m).

It’s a vertical desert of thorny cacti and dusty switchbacks for the first hours of morning light, but the landscape becomes exceedingly greener the higher I climb. By the time I reach the remote village of Marampata that afternoon, I’ve entered a high-altitude jungle.

About a hundred people have etched out a meagre existence in Marampata, some two days away from the closest road and far removed from modern comforts. Marampata is the gatekeeper to Choquequirao and home to the humble headquarters of the archaeological park that protects it. This hilltop settlement also has a basic campground and a store to purchase whatever provisions may have been hoofed up to these Andean heights in recent days by pack mules.

“Some historians believe this hidden outpost was the last refuge of the Inca”

© Choquequirau | Getty

depiction of a llama at the site

I overnight in Marampata and am awake on day three in time to arrive at the ruins for sunrise. I’ve prepared a traditional cup of coca tea (from the leaf used to make cocaine) to stave off altitude sickness. It serves the additional purpose of jolting me awake with euphoria by the time the archaeological site’s tumbling terraces come into view.

Sprawled across three hilltops and 12 sectors, Choquequirao is less immediately photogenic than Machu Picchu. But this towering citadel, occasionally buried within the clouds, offers a level of solitude unimaginable at most ancient marvels. It also has innumerable tentacles for would-be archaeologists to explore. Abandoned in the mid-16th century, it was ‘rediscovered’ several times over the intervening three centuries before preservation efforts began in earnest in 1992. Modern archaeologists believe it was geo-cosmically placed in line with its ceremonial sister, Machu Picchu, with a temple and administrative buildings situated around a central square and living quarters clustered further afield.