- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

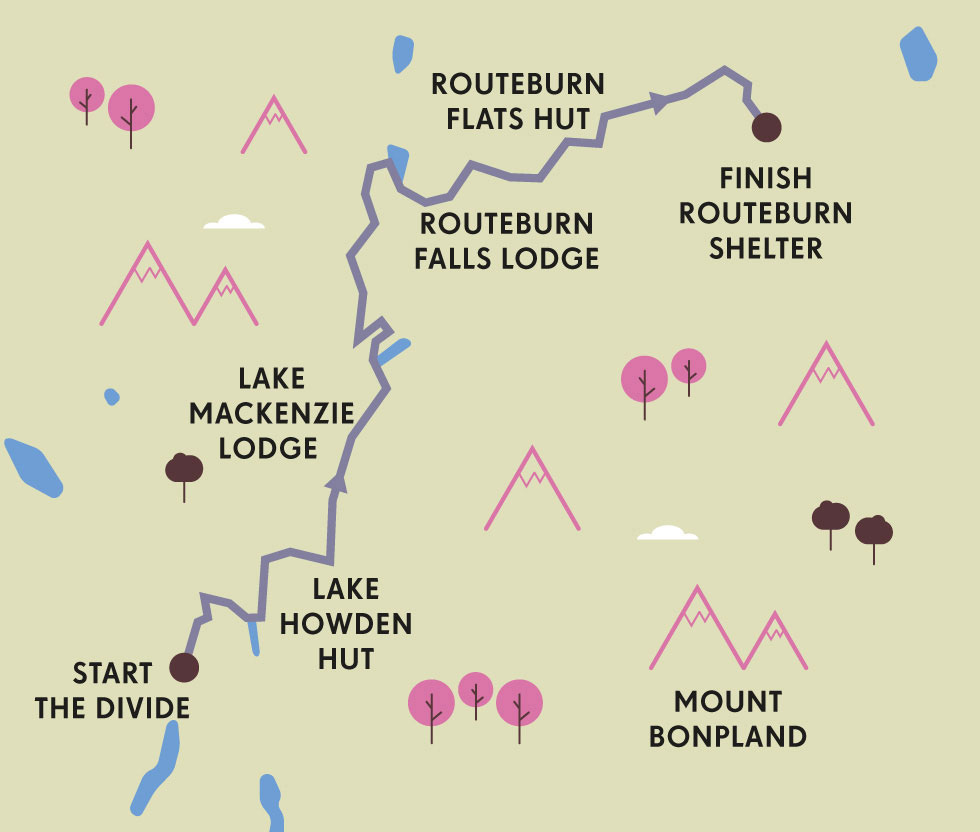

THE ROUTEBURN TRACK

Follow ancient Maori paths through New Zealand’s Southern Alps, where huge flightless birds once roamed and the rivers sparkled with sacred jade.

Alate morning sun appears and disappears through a patchwork of high clouds, revealing a huge bushy expanse stretching hundreds of miles over hilltops and shaded valleys, surrounded by jutting peaks of grey rock.

This is the tail of New Zealand’s mighty Southern Alps, a vast spine of sandstone and granite reaching nearly 300 miles (483km) along the South Island’s western coast. It is remarkably isolated. No roads connect the mountains ahead to the rest of the world. Instead, to explore the peaks, lakes and river valleys that stretch from here in the Fiordland National Park to Mt Aspiring in the west, I must make my way on foot via a thin, winding hiking trail known as the Routeburn Track – a 20-mile (32km), three-day journey through some of New Zealand’s most spectacular landscapes.

In a sloping green valley known as The Divide, the track begins. I set off with boots crunching into skittering gravel and packed earth. The path leads through thick stands of beech trees swathed in drooping moss, crowded in by the outstretched fingers of fern fronds that grasp softly at my knees. The forest is quiet, save for the rhythm of footsteps, my blue waterproof jacket providing a bobbing spot of bright colour in a setting of endless green.

© Philip Lee Harvey | Lonely Planet

a hiker admires the view

The track traces slowly around the northern lip of the Livingstone Mountains and climbs upwards, higher and higher, twisting with the curves of the terrain, to reach the crest of Key Summit. The wind, held at bay until now by the forested slopes, here whips around a broad grassy mountaintop, grabbing handfuls of my hair and buffeting against my eardrums.

crossing a walk bridge on the Routeburn Track

It was along routes like this, climbing high mountain passes and detouring through the surrounding valleys, that the ancient people of this land walked hundreds of years ago. Hardy Maori hunters forged paths through the thick foliage in search of great boulders of pounamu – known as greenstone or New Zealand jade – lying like forgotten jewels at the bottom of the rivers and lakes stretching from here to the west coast.

Great ridges of snow-topped mountains fill the horizon before me, framing three of these great river valleys, stretching off in different directions – Hollyford to the north, Eglinton to the southwest and the bushy green slopes of the appropriately named Greenstone Valley to the southeast. All are shaped by shifting tectonic plates and the inexorable grinding of colossal glaciers.

I trace along the western flank of the Ailsa Mountains, the path growing steeper with every step. The Maori walked these paths in sandals made of woven cabbage leaves, making their way across 50 miles (80km) of treacherous terrain east to their settlements in Otago. Soon, spray from the thundering deluge of Earland Falls, a great forked waterfall cascading down from nearly 600ft (180m) above, creates a fine mist across the path. It winds up alongside a wide grassy meadow with groves of slender-trunked ribbonwood trees and down into a steep valley, where the night’s rest stop, Lake Mackenzie Lodge, is neatly tucked. Plumes from its chimney promise a warming fireside within.

© Philip Lee Harvey | Lonely Planet

Lake Mackenzie

“A sheer drop of hundreds, then thousands of feet grows with each new switchback”

The next morning I pick up the track with a steep climb up a narrow, zig-zagging path. Alongside, a sheer drop of hundreds, then thousands of feet grows with each new switchback, until I reach a rocky open area overlooking the Hollyford Valley. The near-perpendicular granite slopes of the Darran Mountains line up before me. Sir Edmund Hillary cut his teeth here before making his attempt on Everest in 1953.

For early European settlers, these westernmost reaches were a dark, forbidding place, unmapped and unknown. Today, as I walk up to the grassy hilltop of Harris Saddle, I look out into the rumpled green distance, and it’s clear that great areas of dense forest and scrubland remain as they were hundreds of years ago, still rarely, if ever, visited by humans.

New Zealand is home to some 550 species of moss

It was in remote areas like this that the last of New Zealand’s giant flightless birds, the legendary moa, most likely clung on before succumbing to extinction. With some species growing close to 10ft (3m) tall, like a Jurassic-sized ostrich without wings, moa were considered imaginary – a fanciful story of the Maoris – until discovery in the mid-19th century of their long-necked skeletons up and down the country proved their existence beyond doubt.

I round the ridge overlooking Lake Harris, surrounded by snow-dusted peaks, and past the thundering cascade of Routeburn Falls before coming to the evening’s rest stop at Routeburn Falls Lodge.

Routeburn Falls marks the edge of the treeline at more than 2400ft (750m). When morning light spills over the mountainside and into the valley, it reveals the undefined border where the craggy grey outcroppings of the mountains descend into forest. From here, the track winds alongside shaggy alpine pastures, over springy suspension bridges and through thick green bush, the downward path encouraging a light step after two days of uphill endeavour.

© Naruedom Yaempongsa | Shutterstock

Earland Falls on the Routeburn Track

Before long, a strange noise is heard on the breeze – the rumbling motor of a bus in a nearby car park, sounding rough and foreign to the ears after three days spent isolated in nature – and soon, the Routeburn Track has come to an end.

After a journey of 20 miles (32km), I arrive down on the valley floor, and the soaring highlands above, with all their legends, mysteries and fantastical creatures, are once again out of sight beyond the trees. CL

© Philip Lee Harvey | Lonely Planet

the protected kea, the world’s only alpine parrot

POUNAMU

The moss-green pounamu found here was prized by Maori tribes up and down the country, crafted into jewellery or simply used as currency. Harder than steel, it was also handy for creating the deadliest of weapons, such as razor-sharp axes and broad-bladed clubs called meres, which hung from the wrist with plaited twine and could be used to wrench open an opponent’s skull. It was more valuable than gold.

ORIENTATION

Start // The Divide

End // Routeburn Shelter

Distance // 20 miles (32km)

Duration // Three days

Getting there // The nearest airport is in Queenstown, which is just over an hour from the Routeburn Shelter. Note: most hikers use a drop-off service such as Kiwi Discovery.

When to go // Late October to April.

Where to stay // There are four huts on the track. Book all accommodation passes for huts and campsites in advance.

Where to eat // Take food with you. The huts have basic cooking equipment.

What to take // Sturdy boots, waterproofs, lots of layers, a first-aid kit, food and water are the basics: plan carefully.

More info // www.doc.govt.nz. Lonely Planet’s Hiking & Tramping in New Zealand is also an excellent resource.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

NEW ZEALAND GREAT WALKS

MILFORD TRACK, SOUTH ISLAND

The best-known track in NZ – with its towering peaks, glaciated valleys, rainforests, alpine meadows and spectacular waterfalls – is very popular. That it is not overrun, despite attracting more than 7000 independent hikers every year, is down to a regulation system that keeps people moving while ensuring some level of tranquillity. During the Milford tramping season, from late October to late April, it can only be walked in one direction, from Glade Wharf. Additionally, hikers must stay at Clinton Hut on the first night (even though it’s only an hour from the start) and the trip has to be completed in three nights and four days. All restrictions will pale as you clap eyes on the views towards Mt Fisher, for example, or branch off to take in the awesome Sutherland Falls, or scrabble into the tiny cave under Bell Rock – just a few of the many highlights along the route.

Start // Glade Wharf

End // Sandfly Point

Distance // 53.5km (33 miles)

Duration // Four days

KEPLER TRACK

One of three Great Walks within Fiordland, the Kepler was built to take pressure off the Milford and Routeburn. Many trampers say it rivals them both. This alpine crossing takes you from the peaceful, beech-forested shores of lakes Te Anau and Manapouri to high tussock-lands and over Mt Luxmore. The route can be covered in four days, spending a night at each of the three huts. Eye-popping sights include towering limestone bluffs, razor-edged ridges, panoramas galore and crazy caves. The Kepler is a truly spectacular way to appreciate the grandeur of NZ’s finest and most vast wilderness.

Start/End // Lake Te Anau control gates

Distance // 37 miles (60km)

Duration // Four days

a giant sculpture of a takahē stalks the streets of the Fiordland town of Te Anau

LAKE WAIKAREMOANA TRACK

Remote, immense and shrouded in mist, Te Urewara National Park encompasses the largest tract of virgin forest on the North Island. The park’s highlight is Lake Waikaremoana (‘Sea of Rippling Waters’), a deep, 55-sq-km (21-sq-mile) crucible of water encircled by the Lake Waikaremoana Track. Along the way it passes through ancient rainforest and reedy inlets, and traverses gnarly ridges, including the famous Panekiri Bluff, from where there are stupendous views of the lake and endless forested peaks and valleys. Due to increasing popularity, in 2001 the track was designated a Great Walk requiring advance bookings.

Start // Onepoto

End // Hopuruahine Landing

Distance // 28.6 miles (46km)

Duration // Four days

.jpg)

© Filip Fuxa | Shutterstock

Mitre Peak rising from the Milford Sound fiord in Fiordland National Park

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

SYDNEY’S SEVEN BRIDGES

Circle shimmering Sydney Harbour in a 17-mile (27km) loop, crossing iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge (and six others), taking in historic urban areas, beaches, bush and more.

I’ve been a bit of a bridge geek ever since building one out of popsicle sticks in grade school science class, so getting to see seven up close is more thrilling than I’d like to admit. This hike is best known as part of a yearly event called the Sydney Seven Bridges Walk, which raises money for cancer research. But my husband and I have decided to tackle it on an ordinary Tuesday in November.

We live near Sydney’s CBD (Central Business District), so we decide to start the hike at its southeastern point, Pyrmont Bridge. Crossing Cockle Bay in the shiny entertainment district of Darling Harbour, the pedestrian-only Pyrmont, festively decked in coloured flags, looks more like a wide beach pier than a traditional urban bridge. Opened in 1902, it’s one of the oldest working examples of an electric swing bridge, which means its middle chunk swings open to allow tall boats to pass. We don’t get to see that in action today, but we do get a good eyeful of the pleasure yachts that moor here in the shadow of the CBD’s modern skyscrapers. Crossing the bridge, we edge around the top of Pyrmont peninsula, passing wharves that once smelled of fish and reverberated with the sounds of shipbuilding. Today they’re upmarket apartments and cafes, and many of the adjacent warehouses have been razed and replaced with waterfront green space.

Turning the bend to the western side of Pyrmont, we see it in all its glory: the Anzac Bridge. The Sydney Harbour Bridge may be the city’s most famous, but true bridge geeks dig the Anzac more, with its cables like strings on a massive harp. The 2640ft (805m) bridge honours the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), which fought WWI’s Battle of Gallipoli. Far above our heads, an Australian flag flutters against the clear blue sky on the bridge’s eastern pylon, while a New Zealand flag ripples on the western pylon. Walking on the pedestrian lane beside eight lanes of Sydney morning traffic, we have views over the disused Glebe Island Bridge, which has sat rusting at the mouth of Rozelle Bay for more than two decades.

We exit the Anzac and we’re in Rozelle. We wander the residential backstreets of this rapidly gentrifying neighbourhood, where traditional brick bungalows and wooden cottages sit cheek-to-jowl with modernist boxes of glass and concrete. At the peninsula’s western edge, we enter Callan Park. Here, a complex of neoclassical sandstone buildings sits eerily quiet amid lush, slightly gone-to-seed parkland. Once the Callan Park Hospital for the Insane, the buildings are now home to an arts college. People say the area is haunted, and it’s easy to believe. Somewhere in the distance, an ice-cream truck plays a tinny version of ‘Greensleeves’ over and over. I shudder slightly and wipe sweat from my face. It’s midday now, and getting hot.

© Pete Seaward | Lonely Planet

the opera house peeks from below Sydney Harbour Bridge

Next up is the Iron Cove Bridge, a mid-century art deco beauty. A second Iron Cove Bridge, opened in 2011, runs parallel. We choose to cross the older bridge, huffing up the stairs and on to the pedestrian walkway. Exiting into the upscale residential neighbourhood of Drummoyne, we stop for flat whites at a cafe in a shopping complex overlooking the Parramatta River. The water is dotted with tiny islands, including Cockatoo Island, home to a 19th-century prison, and Spectacle Island, once used for manufacturing naval explosives.

The next bridge, the tall, graceful Gladesville, offers even more spectacular views (and quite a quad burn too). The afternoon is clear enough for us to see all the way down to the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the CBD some 4 miles (6km) away. The bridge itself is a 1900ft (579m) concrete arch, once the longest of its kind. Elegant white sailing boats glide through the deep blue waters below and ferries chug along, carrying passengers from one suburb to the next.

© Sandra Lass | Shutterstock

a kookaburra sits on a suburban gate post

In quick succession we zip across the Tarban Creek Bridge and the Fig Tree Bridge, a span bridge and a girder bridge respectively. From the footpath we goggle at the real estate of Sydney’s North Shore – multimillion-dollar houses tucked into hillsides of gum trees and jacarandas, paths leading to docks where sailing boats and speedboats bob patiently. Just beneath the Fig Tree Bridge is Fig Tree House, a turreted yellow cottage built in the 1830s by Mary Reibey, who arrived in Australia as a convict in 1792 and made her fortune in shipping (you can see her picture on the AU$20 note).

© Jason Freeman | Alamy

enjoying the shade from palm trees

“The mighty steel arch stretches across the harbour between pylons of Australian granite”

PORT JACKSON

Sydney Harbour is part of a larger body of water known as Port Jackson (though the entire area is often referred to colloquially as Sydney Harbour). It’s 12 miles (19km) long, extending from its western tributary, the Parramatta River, to the Sydney Heads, where it opens into the Tasman Sea. Geologically, it’s a ‘ria’, a river valley flooded thousands of years ago. Much of Sydney’s colonial history took place along its banks, which are now home to the most densely settled parts of the city.

The next two hours are bridge-less, as we traverse the neighbourhoods of the North Shore. There’s a lot more real-estate gawking to be done here as we wind through well-heeled streets overlooking the harbour. The highlight of this section is a bushwalk beneath a canopy of gnarled gum trees along Tambourine Bay.

Finally, we drop down through North Sydney to Milson’s Point and the star of the show comes into view: the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The mighty steel arch stretches across the harbour between pylons of Australian granite, a testament to the power of engineering. It opened in 1932 to great fanfare, with as many as a million Australians gathering to watch flotillas and sing specially composed bridge anthems. From up here it’s a feast of iconic Sydney landmarks: the Opera House just to the east, the vintage carnival lights of Luna Park below, the ferries of Circular Quay across the water.

© ArliftAtoz2205 | Shutterstock

Luna Park and Sydney’s north shore

Coming full circle with a stroll among the 19th-century terrace houses of The Rocks, we sit down at a local pizzeria to revel in our achievement over pizza with pumpkin and sausage. First, a toast: to bridges, to engineering, to the glorious city of Sydney. EM

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Pyrmont Bridge (or anywhere along the loop)

Distance // 17 miles (27km)

Getting there // Sydney International Airport is about 4 miles (7km) south of the city centre, connected by bus and rail.

When to go // Sydney is generally pleasant year-round, but its mild winters (Jun–Aug) are especially nice for hiking.

Where to stay // If you plan on starting the walk at the Sydney Harbour Bridge or Pyrmont Bridge, staying in or near the CBD would be most convenient.

What to take // Wear long sleeves and a floppy hat. And as any Sydneysider will tell you, it pays to carry sunscreen.

More info // Cancer Council NSW hosts a Seven Bridges Walk to raise money for cancer research each spring. Their website (www.7bridgeswalk.com.au) has a detailed map of the trail. If you’re in town for the actual event, sign up!

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

AUSTRALIAN CITY HIKES

BONDI TO COOGEE WALK, SYDNEY

Explore two of Sydney’s most famous beaches on this beloved 4-mile (6km) paved urban trail. Start in Bondi, the pin-up model of Sydney beaches, with a bracing swim in the blue-green surf and an exploration of the tidal pools on the northeastern rocks. From here you’ll wind south along a clifftop path edging Sydney’s posh eastern suburbs. Heading out of Bondi, don’t miss the Aboriginal rock carving of a shark or whale on your left. About 15 minutes later you’ll hit the beach town of Tamarama, home to the tanned and toned surf set. A bit further on, at Bronte, check out the ‘bogey hole’ (rock pool) on the beach’s south end. Ramble another mile or so along the rocky, scrub-covered cliffs to Clovelly Beach, working up a bit of a sweat on the steep stairs, then on to busy Coogee. Celebrate with a dip in one of the beach’s aqua rock pools and a beer at one of the cafes set back from the sand.

Start // Bondi Beach

End // Coogee Beach

Distance // 4 miles (6km)

© Production Perig | Shutterstock

hanging at Bronte Beach, Sydney

CAPITAL CITY TRAIL, MELBOURNE

This 18-mile (29km) loop circles central Melbourne, running along the Yarra River and Merri Creek much of the way. It’s an urban trail, which means walking under highways and over bridges, following train tracks and passing walls covered in graffiti. It’s all part of the charm. You’ll pass directly by or near many of Melbourne’s top sights, including the Royal Botanic Gardens, the Melbourne Zoo and the Abbotsford Convent complex, an imposing former convent turned mixed-use arts and entertainment centre with an adjacent children’s farm.

Start/End // Princes Bridge near Flinders St Station (this is a popular and convenient starting point, but you can start wherever you’d like)

Distance // 18 miles (29km)

© Guillem Lopez Borras | Shutterstock

rowing on the Yarra River, Melbourne

DARWIN CITY TRAIL

Languorously located on the shores of the tropical Timor Sea, Darwin has a frontier feel that’s only enhanced by knowledge that dinosaur-proportioned saltwater crocodiles inhabit the creeks and sometimes sunbathe on the city’s beaches. Built on a headland, it’s ideal for foot-based exploration. After hand-feeding wild fish at Doctors Gully, wander east through Bicentennial Park to tunnels built into Darwin’s cliffs during WWII. At the Waterfront, plunge into a croc-free saltwater lagoon or surf some breaks in the wave pool. Continue around the headland and bear east to Charles Darwin National Park, adding a bushwalk to this urban adventure, before cutting back across towards Fannie Bay to the Museum and Art Gallery, where fascinating exhibits include a terrifying immersive experience about Cyclone Tracy, which flattened the city over Christmas 1974. End your mooch at Mindil Market, where Darwin’s melange of cultures and cuisines fuse together in a spectacular fashion.

Start // Doctors Gully

End // Mindil Beach

Distance // 12.4 miles (20km) or more

More info // www.northernterritory.com

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

THE GREAT SOUTH WEST WALK

Lose yourself to Australia’s natural world and find wildlife wonders aplenty in this multiday hike through southwest Victoria’s lush landscapes of forest, river, beach and bush.

After stretching my legs and lungs along the clifftops and beaches of Portland Bay, I turn into the lush greenery of Cobboboonee National Park. At first all I hear is the leafy shuffle of my feet on the path, but gradually the quiet of the bush envelops me with rustling and soft calls. And then I hear something scary…the sound of padding feet and a soft drumming behind me. Carefully turning around I lock eyes with a tall, elegant and beautifully clad local – an emu, making a weird noise in its throat! Head cocked to the side, checking me out, it seems quite unconcerned about sharing the track. So I move on slowly until I find an open space where I can stand aside, then watch as it saunters slowly by, giving me a cursory glance as only a real local would. This was just the start of a walk that would sharpen my senses to the ‘sounds of silence’ and give me time to reflect on my place in a world that already seemed far away.

The Great South West Walk is a 155-mile (250km) loop in Victoria state’s southwest corner. It unwinds through breathtaking landscapes of towering gum trees, a river of untouched beauty, magnificent ocean beaches and cliffs, and a magical world of flowering native bush. It also offers numerous shorter walks, so you can walk as little or as much as you like. At a gentle pace, the whole hike takes between 11 and 14 days, and most of it is easy going.

© Sandy Goddard

the winding Glenelg River

I wasn’t sure when I set out if I was going to do the whole walk, but now that I’m here, I just want to keep going. I feel like I’m connecting with nature; walking, sleeping and waking with it all around me. And as I blend into the natural world around me, I become more aware of the animals, birds and insects everywhere; this walk is famous for its wildlife and I’m seeing dozens of emus and countless wallabies, kangaroos, echidnas and koalas, and none of them seem worried by my presence. And the shuffling and hooting of possums and owls are guaranteed night-time sound effects. I even start to feel a bit like an animal myself, moving quietly through the bush, sneaking up on fellow creatures to see how close I can get to them.

Soon I find myself alongside the serenity of the wide Glenelg River as it winds its way through gleaming limestone cliffs and enormous gorges. I’m having trouble keeping up with the birdwatching – so many sounds and sightings…wrens, robins, ducks, egrets, wedge-tailed eagles, friendly bristlebirds, and a rare sighting of the endangered red-tailed black cockatoo, to name just a few. I’m not keeping count but I’ve heard that serious birdwatchers have noted 110 different bird species along this walk.

© Sandy Goddard

capes and cliffs of Discovery Bay

I watch groups in canoes gliding by in this beautiful riverscape and feel a stab of envy; another perfect way of being alone among nature. Some of the river campsites are only accessible by walking or water, which makes this river trek section even more exotic. After a night at the historic Pattersons Canoe Camp, established in the 1920s by the Patterson family of Warrock Station, I head into the small town of Nelson to stock up on supplies and overnight with a hot shower at the local campsite.

Next morning I’m up early and on my way along Discovery Bay beach, with crashing waves, flocks of seabirds, and a salty wind providing an exhilarating soundscape. This is a beachcomber’s paradise, and I see lots of curios among the flotilla of whale bones and exotic debris. There are remnants of other life too; walking through huge coastal dunes, some up to 230ft (70m) high, I spy an ancient Aboriginal midden site with scattered shells and pieces of flint from toolmaking, reminding me of the rich cultural history here.

ANCIENT LANDSCAPE

As you walk through the colossal sand dunes near Swan Lake, on Discovery Bay, you will pass flat beds of grey soil that have been exposed by the moving sand. These are actually the remains of ash from local volcanic eruptions that happened more than 5000 yeas ago. Middens of shells and flint chips, found near these deposits and along the clifftops, show that Gunditjmara Aboriginal people were living in this area over 11,000 years ago. If you happen to come across one of these middens, don’t disturb it.

© Nicole Patience | Shutterstock

Halfway along Discovery Bay I have the choice of continuing on the coastal trail or heading inland; I choose the latter, and am soon surrounded by massive gum trees and the fabulous flora of Mt Richmond National Park, where one minute I’m staring up at two koalas in a eucalyptus tree, the next spotting a flock of New Holland honeyeaters feasting on the enormous flowering spikes of grass trees. As I’m absorbing the colours and shapes of some beautiful wildflowers, I notice a tiny, exquisite native orchid at my feet.

© Kat Clay | Getty

meet New Holland honeyeaters and wild emus

This wonderland of bush botany and wildlife gives way to rolling grasslands as I head towards the rugged cliffs of Cape Bridgewater. The views of the wild southern ocean are spectacular from these huge volcanic cliffs, and equally intriging are the pumping blowholes, a petrified forest and the noisy but cute seal colony that has both Australian and New Zealand residents.

© Colacat | Shutterstock

the petrified forest

My return to the real world starts via the small but lovely Bridgewater Bay village, before heading out along the clifftops to Cape Nelson and the welcome smells of coffee and food from the cafe at the base of an historic lighthouse. It’s here that I learn how work started on the GSWW in 1981, and for the past 35 years has been maintained by a group of local volunteers. The Friends of the Great South West Walk are mainly retired men who travel out to do track maintenance on a weekly basis. And at the time of writing this, one of its original founders, Bill Golding, is still pulling on his boots and gloves as part of this dedicated team.

Finally, I’m strolling along the last part of my journey – heading to Portland on a coastal track, watching for whales, surfers and diving gannets. I’m almost at the end of this wonderful walk, and feeling like a different person. There’s no doubt that losing myself among the nature here has refreshed my body, mind and soul. SN

“I feel like I’m connecting with nature; walking, sleeping and waking with it all around me”

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Portland – you can walk in either direction.

Distance // 155 miles (250km), but with the option of lots of shorter 6–13-mile (10–22km) walks too.

Getting there // Portland is 222 miles (357km) southwest of Melbourne. You can fly or there’s a daily train service to Warrnambool, with connecting coach to Portland.

When to go // September to March.

What to take // Binoculars, sturdy walking boots, camping supplies, insect repellent, sunscreen.

Where to stay // There are 14 well-kept campsites along the trail that come with shelter, picnic table, eco toilet, fresh rainwater tank and a fire pit.

More info // Friends of the GSWW (www.greatsouthwestwalk.com) for general information, links and helpful phone numbers for planning.

Things to know // Most campsites are in state or national parks and require bookings and payment through the Parks Victoria website at www.parkstay.vic.gov.au/gsww.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

VICTORIAN HIKES

DESERT DISCOVERY WALK

This four-day walk is through surprising landscapes in the semi-arid Mallee region of western Victoria. Despite the semi-aridity, the Little Desert National Park is anything but barren, with vast areas of native wildflowers, Flame heath and woodlands of yellow gum and slender cypress found in its heathlands, salt lakes, rolling dunes, dry woodlands and river red gum forests. The range of birdlife is amazing too; from the tiny blue wren, exotic gang-gang cockatoos and honeyeaters to the fascinating mound-building malleefowl. You literally wake and retire to birdsong. The full 52-mile (84km) trek is best suited to experienced walkers, but there are options for one- to four-day hikes, and two campsites along the way. Avoid the summer, which gets very hot.

Start/End // Horseshoe Bend camping ground, Kiata

Distance // 52 miles (84km)

CROSSCUT SAW AND MT SPECULATION

This is one of the must-do hikes in the scenic Alpine National Park. Starting at Upper Howqua Camping Area, it crosses the Howqua River several times, before a challenging climb up Howitt Spur to Mt Howitt. The trail then traverses the jagged angles of the Crosscut Saw, which include the interestingly named Mt Buggery and Horrible Gap, then a steep hike up to Mt Speculation. The breathtaking panoramas of the Australian Alps and the remote and spectacular Razor Viking Wilderness are unforgettable. The return is back across the Crosscut Saw to Mt Howitt and then either down Thorn Range or via Howitt Spur back to the Upper Howqua Camping Area. Walkers usually overnight at the two campsites, the first at Macalister Springs, and the other at Mt Speculation. Best done over three days in November to April.

Start/End // Upper Howqua Camping Area

Distance // Approx 24 miles (38km)

© Bjorn Svensson | Alamy

autumn colours in the Australian alps

SEALERS COVE

The Prom, at the southernmost tip of Australia, has spectacular scenery of all kinds; huge granite mountains, pristine rainforest, sweeping beaches and coastlines. There are some great walks from the Tidal River campground, and Sealers Cove is one of the best, often described as a ‘walker’s paradise.’ That’s partly because it’s accessible only by boat or on foot, but also because it boasts clear turquoise waters, golden sand, a shady idyllic campsite and arresting wildlife. On the upward walk there are spectacular views and lush rainforest before heading downhill to the coast. It’s about three hours each way, but birdwatchers and plant lovers will want to do it at a more leisurely pace to make time for all the photos. The track is good year round, with boardwalks across winter streams, but the best walking weather is spring and autumn.

Start // Tidal River

End // Sealers Cove

Distance // 8 miles (12.5km)

© Givenworks | Getty

Sealers Cove

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

TASMANIA’S THREE CAPES TRACK

Weave through dense forest above pounding surf and soaring dolerite cliffs to taste the wilderness of Australia’s Tasman Peninsula on an epic but achievable four-day trek.

The welcoming committee on the Three Capes Track was quite something. Tree martins swooped in salute, gobbling kelp flies alongside towering cliffs. New Zealand fur seals bobbed in the coves, waving hind flippers above the waves. And a juvenile sea eagle stood to attention on a stump, peering along its fearsome bill as stern as any royal sentry.

It was a dramatic transition from the bustling precincts of Port Arthur Historic Site. At that atmospheric spot, a Victorian-era penal colony where the most hardened convicts once toiled, I joined hikers boarding a small boat for the 75-minute voyage to the trail’s official start. Easing away from the looming penitentiary, we rounded the eerie Isle of the Dead – where more than 1200 transportees lie buried, thousands of miles from home – and admired those birds and seals before being dropped alongside the cobalt waters of Denmans Cove.

Here begins one of Tasmania’s newest and most alluring treks. The Three Capes Track is an accessible introduction to wilderness walking, somewhere between rufty-tufty camping trails and the gourmet lodge-to-lodge packages such as those on Maria Island and the Bay of Fires. Over 29 miles (46km) and four days, walkers encounter sea cliffs, aromatic eucalypt forest and leech-infested rainforest, windswept heath and two of the three titular capes (the other, Cape Raoul, is visible but not visited, though it will be included in a mooted route extension). Accommodation is in three custom-built cabin sites, with simple, comfy bunkrooms and well-equipped kitchen and toilet blocks – bring a sleeping bag and food, but none of the other paraphernalia required on a hardcore plunge into Tasmania’s more-remote wildernesses.

© RooM the Agency | Alamy

approaching the destination at Fortescue Bay

The walking and landscapes, though, are epic enough from the off. From gorgeous Denmans Cove I traced the path through ghostly gum woods, Port Arthur Bay just discernible through the spooky mist. On that first day I tramped a gentle 2.5 miles (4km) to Surveyors, the first of the three cabin sites, each with different but alluring views. That night I munched dinner on the open deck, gazing across heath grazed by Bennett’s wallabies, west to the craggy columns of Cape Raoul, and east to the hump of Arthur’s Peak – the next day’s main challenge.

© Peter Gudella | Shutterstock

Cape Raoul

The Three Capes Track could generously be described as undulating. There are no huge summits to conquer, but instead a rolling trail, sometimes on well-maintained dirt or rocky paths, elsewhere along springy wooden boardwalks. The second day’s hike led first through more eucalypt forest, where first a wallaby then a bronze skink darted off the path ahead, to a curious sculpture – the first of some 37 ‘Encounters on the Edge’ studding the trail. Each was created especially for the track, and reflects an aspect of the area’s human or natural heritage. ‘Punishment to Playground’ is a bench filled with snorkel masks, fishing reels and golf clubs, a nod to the changing function of nearby Point Puer; today a golf course, until 1849 it was the site of a boys’ prison. A little further on came a pile of large, smooth wooden cubes: ‘Who Was Here?’, a reminder to look for the square poos of snuffling wombats.

“That night I munched dinner in the open, gazing across the craggy columns of Cape Raoul and the hump of Arthur’s Peak”

Through scrub and forest scented with eucalypt and tea tree I climbed, to be rewarded with a sweeping new vista to Cape Pillar, the next day’s objective. Habitats morphed almost minute by minute: stands of stringybark and mossy forests, cliffs where signs indicated nesting sea eagles, more heath and dense woods where yellow-tailed black cockatoos squawked overhead.

That night at Munro cabin, I peered along the coast to cape number three, Hauy, and listened to surf pounding the cliffs and wind howling through the treetops. The weather was turning fast – as it does in Tassie – but it failed to turn back overnight, and next morning I set out through thick cloud and stinging mizzle. The third day is an out-and-back from Munro along the narrow peninsula to Cape Pillar, traversing a path lined with trees bent by fierce winds that scream around the cape. Shapes and sounds were rendered soft and deceptive by the mist: a flash of brown might have been a wallaby hopping off the trail, the calls of birds blending with a chorus of frogs in a nearby billabong.

© Kevin Wells | Alamy

a Bennett’s wallaby peers from the bracken

THE LONELIEST LIGHTHOUSE

Atop Tasman Island off Cape Pillar perches Australia’s loftiest lighthouse. Thanks to sheer dolerite cliffs soaring to 985ft (300m), construction proved an epic challenge: it was nearly 40 years after the initial survey that the prefabricated cast-iron lighthouse first glowed in 1906. Life on this storm-lashed rock was harsh; Jessie Johnston, the first keeper’s wife, dubbed it ‘Siberia of the south’, and communications to the Tasmanian mainland were initially limited to signal flags. The light was automated in 1976.

Nervously I clambered up the sheer-sided ridge named the Blade to reach the cape itself, where the cloud lifted just long enough to reveal a dizzying drop and Tasman Island beyond, the lighthouse-capped, desolate lump of rock dangling off the end of the peninsula. Then the clouds descended once more, and I tramped back to Munro to pick up my pack for the short leg to Retakunna cabin, that last night’s stop.

Some creatures, of course, love rain – and on my last morning I had unwelcome encounters with several. In the wet forest below Retakunna battalions of leeches wiggled, latching on to my bare knees till rivulets of blood trickled down my shins. No matter. The mossy, ferny forest is magical enough to counter any parasite loathing. Soon I re-emerged on to the cliffs, soul salved by views back to Cape Pillar and across to Mt Fortescue, the final haul.

Cape Hauy itself, an hour’s detour from the main track, was a suitably epic finale: pillars erupted from the spume, tempting rock climbers who tackle the aptly named Totem Pole. For me, though, the end was in sight – figuratively and literally: Fortescue Bay, where I baptised my weary feet in the warm waters lapping the sand. Three capes, two legs: one spectacular introduction to the Tasmanian wilderness. PB

© TassieKarin | Getty

the pillars of Cape Hauy

ORIENTATION

Start // Denmans Cove

End // Fortescue Bay

Distance // 28.5 miles (46km)

Getting there // The four-day package starts and ends in Port Arthur, and includes a boat to the trailhead and return bus from Fortescue Bay. Port Arthur is 59 miles (95km, 90-minute drive) from Hobart, Tasmania’s capital, a little less from Hobart Airport. Daily Tassielink (www.tassielink.com.au), Gray Line (www.grayline.com.au) and Pennicott Journeys (www.pennicottjourneys.com.au/three-capes-track) buses serve Port Arthur from Hobart.

Tours // Currently, the trek is available self-guided only, and places must be booked through the official website (http://threecapestrack.com.au). The fee includes transport to and from the trailhead and end point, as well as accommodation and a guide book. From September 2018, guided, catered tours will be available with Tasmanian Walking Co (www.taswalkingco.com.au/three-capes-lodge-walk).

When to go // The warmer months (Nov–Apr) offer better, though far from guaranteed, weather.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

TASMANIAN TREKS

OVERLAND TRACK

The five- to seven-day hike from Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair is the classic Tassie trek. Traversing a region opened up by Austrian Gustav Weindorfer, who extolled its glories a century ago, its dramatic landscapes are dominated by iconic Cradle Mountain and 5305ft (1617m) Mt Ossa, the island’s loftiest peak. Expect boggy trails, strong winds, rapid weather variations and ample wildlife – wombats are ubiquitous around Cradle Valley, and you’ll likely spy pademelons and possums, though you’d be fortunate to spot the quolls, echidnas and Tasmanian devils that lurk in the park. Also expect crowds, particularly in peak season (1 October to 31 May), when booking is essential. With limited spaces in basic huts, most hikers camp and all supplies must be carried, though you can join a guided, catered trek staying in comfortable lodges. Either way, you’ll experience Tasmanian wilderness at its most elemental.

Start // Ronny Creek, Cradle Valley

End // Narcissus Hut or Cynthia Bay

Distance // 40 miles (65km) or 51 miles (82km)

More info // www.parks.tas.gov.au

© Catherine Sutherland | Lonely Planet

on the Overland Track, a boardwalk section winds through Cradle Valley

FREYCINET PENINSULA CIRCUIT

Against stiff competition, arguably Tasmania’s most magical beach fringes the Freycinet Peninsula on the east coast. Wineglass Bay is just one of several glorious strands lining this two-day circuit. Despite the long stretches of surf-lapped sand, don’t expect pancake-flat walking – the trail crosses hilly inland areas and the craggy Hazards Mountains, and you must carry your tent and all food. But the rewards are luminous: ample paddling potential at the beaches of Hazards, Cooks and Bryans (a short detour), far-reaching views from Mt Freycinet, bustling birdlife and of course the perfect crescent of sand at Wineglass Bay itself. If time or energy are limited, take a shortcut along the Isthmus Track between Hazards Beach and Wineglass Bay for a delightful five-hour outing.

Start/End // Wineglass Bay car park

Distance // 19 miles (30km)

More info // www.parks.tas.gov.au

SOUTH COAST TRACK

Overland Track not challenging enough? Try tackling this trail snaking along the coast of isolated, untouched Southwest National Park. For experienced bushwalkers only, this six- to eight-day trek is tricksy right from the off – there are no roads to the trailhead at Melaleuca, so you must either fly or hike in. You’ll need to bring camping gear, wet-weather and warm clothing, all food and a hardy constitution: weather can be wild, trails muddy, beach and creek crossings unpredictable, leeches persistent and ascents demanding, not least the 2970ft (905m) haul up the Ironbound Ranges. But what a trek. You’ll traverse pristine, empty beaches, dense forests and soaring peaks, and watch rare wildlife – including in summer, if you’re really lucky, critically endangered orange-bellied parrots, which breed in tiny numbers only at one spot.

Start // Melaleuca

End // Cockle Bay

Distance // 53 miles (85km)

More info // www.parks.tas.gov.au

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

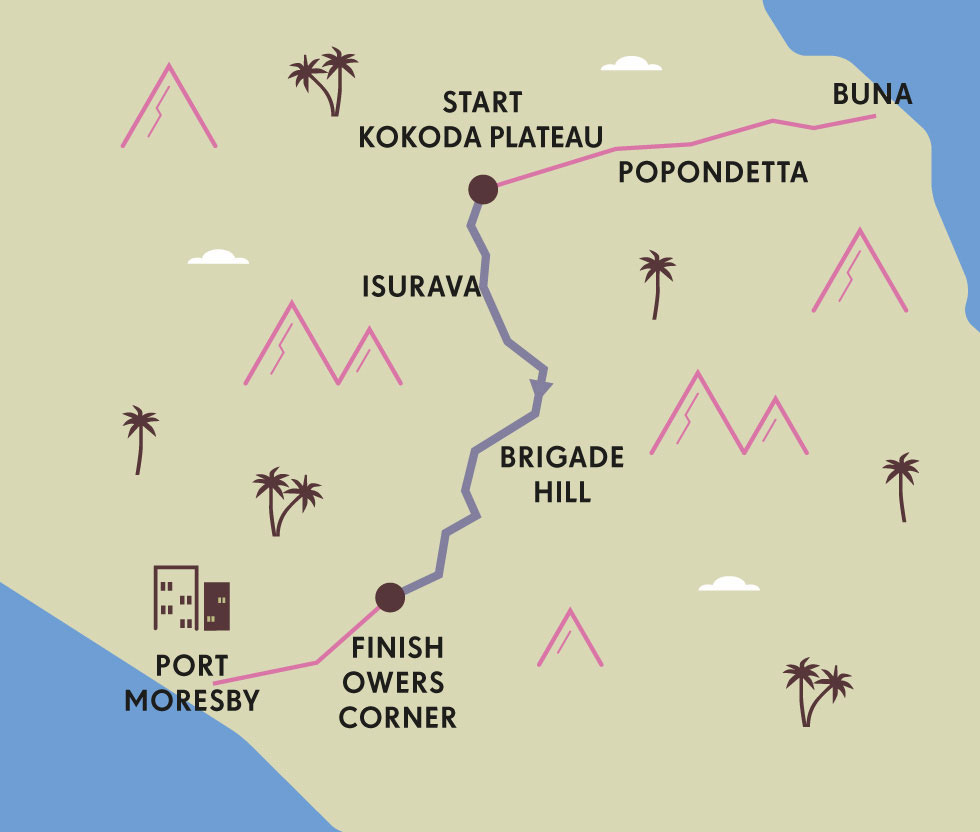

WAR AND PEACE: THE KOKODA TRACK

Moving from azure beaches, to misty mountains through jungle that’s every type of green, this trek in southern Papua New Guinea is an immersive mix of modern history and Papuan culture.

Part-way up the biggest incline on the fourth day, my legs start to feel it. I pause and raise my eyes along the steep muddy jungle track to a misty clearing at the top where some porters have gathered to wait for us. Apes Turia, the 49-year-old head porter, pulls his acoustic guitar from the side of his pack; this is his 104th Kokoda trek. As he strums a few chords and sings in his local dialect, the other porters join in. Their perfect harmonies melt down the mountainside and through the canopy, scooping us all up, somehow delivering us to the peak, beaming and momentarily ache-free. There is no better way to reach this mountaintop here; somehow the music captures the trek and the landscape perfectly, and adds poignancy to the moment we emerge. We’re greeted by a breathtaking view back through the valley, small villages dotting an infinite number of greens that perforate the blue horizon.

© Ryan Stuart

cloud threatens to envelop Nauro village

Our starting point at the Northern Beaches village of Buna now seems a different world. Just a few days before, I was ticking off tropical clichés as I sat on a crooked palm tree watching local kids play and scream in the crystal-blue water. An old fisherman dragged his nets into his canoe in the distance, and a local woman – Jean – cleaned her pots at the shore with a mixture of sand and leaves. The village sits at the water’s edge. Sand stained light grey from distant volcanic eruptions creeps out to sea a few metres before falling off to near white, giving the water its magical blue colouring. Aside from being a startlingly beautiful place to acclimatise to the tropical conditions (and a rare opportunity to spend a few days living amongst locals in a Papua New Guinean village) there are other reasons to start here. Buna and its neighbouring villages were the site of the initial Japanese beach landings at the start of the Kokoda campaign in July 1942, during WWII. Attempting to attack the capital, Port Moresby in the south, Japanese forces chose the Kokoda track as their route. Predominantly Australian Allied forces launched a counter-offensive from Moresby and the two sides each gained and lost significant ground along almost the entire length of the track over six months. The campaign ended with a Japanese withdrawal from these same beaches.

© Ryan Stuart

the trek leader looks back over the Kokoda Plateau

Veterans on both sides recount that battling the terrain was as hard as the fight with their enemies, and it is this reputation that has given the track its mythical status. In Australia, the word Kokoda is synonymous with steep inclines, unforgiving terrain, a tropical climate and both a physical and mental challenge. It winds up and down for 60 miles (96km) through incredible jungle, wetlands, rainforest, villages, rivers and mountains from the Kokoda Plateau at its northern point to Owers Corner to the south. Initially formed as a network of trails used to connect mountain villages, the track is still in active use and you will meet many locals on your way. In fact, the entire track sits on locally owned private land.

the rickety bridge to Eora Creek

“Australian tank tracks are used to edge garden beds and prop up cooking grills”

It also sits somewhere between lore and reality in its own world of Kokoda legend, one that fits in a landscape of mythic proportions: other-worldly geographic forms; huge Pandanus trees towering above the canopy; murky swamps; lush rain forest glens; and, of course, the serrated mountains we traversed each day. There are many stories, but one about an Australian soldier on the track during the Kokoda campaign gives a clue to how steep this country is. During a skirmish he stood up and was shot through the ear and the foot – with the same bullet.

a traditional greeting at Buna village

Passing through a mountain village I met local David, who hunts birds. Standing next to the track, with a slingshot and fistful of stones, his catch was a good addition to the regular diet of corn, potatoes and other vegetables grown in the village, some of which we would buy to supplement the food we carried. Taking a more relaxed pace on the track allowed for these moments, and gave more time to take in the surroundings, experience local culture and gain genuine insight into day-to-day living. One evening after a swim in the stream next to the campsite, I watched a porter, Silver, as he fished. After a quick dig for worms he used a small branch for a rod and a bullet for a sinker. Moments later he pulled out a trout.

many hands make light work of landing at Buna

Living within communities, and walking on local land, the culture is ever present. So too is the history of the Kokoda campaign; from Buna onwards there are signs of it everywhere – out in the open air and part of everyday life, from fox holes, to plane wrecks and supply dumps. Australian tank tracks are used to edge garden beds and prop up cooking grills, every village has its own makeshift war museum attached to someone’s private home, and several times during our trek live ammunition rounds were dislodged from the muddy track when trampled underfoot.

After our final ascent, we walk under the commemorative arch at Owers Corner, and the emotion of finishing takes many by surprise. On the bumpy bus back to Moresby, we all say we’ll come back and walk it again – me with much less camera gear. As others nod off I watch the jungle fade into the distance, power lines slowly creeping into view, as we wind down the mountains and closer to Port Moresby, and our real lives. RS

FLY-BYS ON PARADE

The birds-of-paradise are stunningly beautiful and 40 of the family’s 42 colourful species live in PNG. While their tiny size means they can be hard to spot, porters and locals will be able to help. If you are very lucky you may also spot a much larger bird, the cassowary. Much easier to see are the thousands of different-coloured butterflies, 735 species of which call PNG home.

ORIENTATION

Start/End // Kokoda Plateau/Owers Corner. Walk in either direction.

Distance // 60 miles (96km)

Getting there // Fly into Port Moresby.

Tours // Without the local knowledge of a tour operator travel in PNG is very difficult and potentially unsafe. Try World Expeditions or Escape Trekking Adventures.

When to go // April to November.

What to take // Good boots and poles are essential.

What to wear // Shorts, T-shirts and a light polar fleece for cold mountain evenings. Modest swimwear is important due to local religious beliefs.

More info // www.papuanewguinea.travel; www.dokokoda.com.

Things to know // Allow time for visa processing and hire a porter: it will change your trek experience and supports locals.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

BATTLEGROUND HIKES

FUGITIVES TRAIL, SOUTH AFRICA

The lonely hill of Isandlwana stands sentinel over the grassy, sun-baked KwaZulu-Natal plains. But it also marks the spot of one of the bloodiest battles in British colonial history. On 22 January 1879, during the Anglo-Zulu War, a British garrison was attacked here by a spear-wielding impi (regiment) of Zulu warriors. Outnumbered and unprepared, they were forced to run for their lives across the rugged savannah, through a stream, up a rocky, scrub-cloaked hill and over a raging river, in an attempt to reach safety. It was a gruesome skirmish. Most did not make it; many Zulu were killed too. And now the route of this infamous retreat is scattered with whitewashed cairns marking the spots where soldiers fell. It’s a chilling but fascinating hike, best done with an expert guide to bring the grim history to life.

Start // Isandlwana

End // Buffalo River

Distance // 5 miles (8km)

© Sven Hansche | Shutterstock

British war graves on Isandlwana Hill, South Africa

ALTA VIA 1, ITALY

During WWI, the spiky grey peaks of the Dolomites became the most beautiful – if hostile – of battlefields. Between 1915 and 1918, Italian and Austro-Hungarian/German forces faced off in these magnificent mountains, enduring the freezing cold, precipitous terrain and lung-testing altitudes while also fighting for their countries and their lives. In order to be able to wage war here, they constructed tunnels, trenches and encampments, as well as via ferrata (iron roads), a network of metal ladders, rungs and fixed lines that enabled them to move across the mountainsides. Thankfully the long-distance Alta Via 1 hike is a much more serene way to roam amid these peaks. The route combines the Dolomites’ spectacular lakes, wildflower meadows, high passes and welcoming rifugios with fascinating relics of the mountains’ tragic past.

Start // Lago di Bráies

End // Belluno

Distance // 75 miles (120km)

© ClickAlps Srls | Alamy

following WWI bootsteps in the Dolomites

1066 WALK, ENGLAND

Follow in the footsteps of William the Conqueror across the high weald of East Sussex. In September 1066, William (then Duke of Normandy) landed at Pevensey Bay on the south coast of England and, one month later, defeated King Harold at the Battle of Hastings. The 1066 Walk explores this history-changing swathe of countryside via an array of little villages, ancient towns, woods, windmills and key sites. It begins at Pevensey Castle, which was a Roman fort in 1066 but was converted into a Norman stronghold by William’s brother. It also passes through the small town of Battle, where the two sides clashed; Battle Abbey was founded here in 1095 to commemorate the conflict. The battlefield became the abbey’s great park, while the abbey church’s high altar supposedly stands on the spot where Harold died.

Start // Pevensey

End // Rye

Distance // 30 miles (50km)

© Michael Heffernan | Lonely Planet

Pevensey Castle in Eastbourne, southern England

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

THE ABEL TASMAN COAST TRACK

One of New Zealand’s Great Walks, this world-class beachcombing caper tiptoes around tides and bounds between the bays and golden coves of the South Island.

If the huge piece of driftwood hadn’t suddenly sprouted a head and let out an indignant snort, I’d have sat on it to eat lunch. Apparently, this log isn’t wood at all. It’s a heaving, breathing, belching lump of grumpy New Zealand fur seal, which had been enjoying a morning snooze under shimmering sun until I ruined its reverie by gatecrashing the secluded beach.

Evidently, my new friend isn’t as excited about our encounter as I am – something he makes cacophonously clear when I begin bagging silly sealy selfies. I keep a respectful distance, not wanting to end up in a fist/flipper fight with 330lb (150kg) of rudely awoken sea mammal, especially not quarterway through a 37-mile (60km) walk, beyond limping range of human habitation or help.

So I leave him to snore and seek an alternative snack spot. Fortunately, picnic possies with epic ocean views are plentiful along the Abel Tasman Coast Track, and before long I stumble into another beautiful bay, gilded by golden sand and gently stroked by the waters of Tasman Bay, a glassy puddle becalmed between the protective arms of Farewell Spit and D’Urville Island.

Once lunch is munched, an internal debate begins: should I have a quick swim, or keep walking towards the hut? And therein lies the problem with this trail, a rambling route through rata forests fringing the coastline of Abel Tasman National Park, linking a series of idyllic coves at the top of New Zealand’s South Island.

The hike isn’t physically tough – not compared with most multiday Kiwi capers – and covering 9 miles (15km) a day allows walkers to enjoy the experience at a comfortable clip. No, here the challenge is different. For round every corner is a beach so fine it would be unforgivable not to stop, strip and plunge into the blue. And then you continue, only to find another sublime bay. And so it goes on.

© Anna Gorin | Getty

footsteps in the golden sands of Marahau

Small wonder the Coast Track is an original member of New Zealand’s much-feted group of Great Walks, a list that features the nation’s top trails. In a country well-endowed with epic hiking routes, it takes something special to feature in this premier league of paths. Tongariro has dramatic volcanoes and multi-coloured mineral-stained lakes; the Routeburn, Kepler and Milford Tracks make the grade through the magnificence of Fiordland; and the Abel Tasman Coast Track gets the nod because it’s one of the world’s best beachcombing adventures.

The walk can be done in either direction, but most people start at Marahau and spend several days strolling north, returning via water taxi from Totaranui. A decade earlier I’d walked the route this way. Then, tramping around New Zealand on a backpacker’s budget and unable to afford the boat transfers, I had continued to Whariwharangi Hut and spent three days trekking back to Marahau via the Abel Tasman Inland Track (a 25-mile/41km path along Evans Ridge and through the beech forests of Moa Park), a more challenging and less trafficked trail than its coastal cousin.

© Guaxinim | Shutterstock

walking the beaches of Abel Tasman

This experience taught me that the top part of the Coast Track offers quieter paths, better vistas and more wildlife encounters than the rest of the route. Armed with this insight and angling for new views, I’ve returned to walk north-to-south, after being dropped off at Wainui Bay. Trekking in this direction involves an extra layer of logistics, but it launches you straight into the wildest sections of the trail, and soon after rounding scenic Separation Point, the decision pays off, as I meet the seal in Mutton Cove.

“Round every corner is a beach so fine it would be unforgivable not to stop, strip and plunge into the blue”

© Janet Teasche | Getty

kayaks at Watering Cove

KAYAKING THE COAST TRACK

The Coast Track is a cracking walk, but Abel Tasman National Park’s shores can also be explored from the cockpit of a sea kayak. Several operators offer combined hiking and paddling adventures, where it’s possible to kayak across translucent lagoons and between bays, before swapping blade for boots and walking back. Marahau to Anchorage Bay is a popular paddling section, with walkers wandering onward usually to Bark Bay or Onetahuti before catching a water taxi back.

My dilemma – to take a dip or dawdle on – begins just around the corner, in Anapai Bay, one of the most beautiful bitemarks found along this whole sensationally serrated shoreline. I don’t hesitate long. Once past Totaranui, I’ll be sharing the huts and the trail with trampers and paddlers aplenty, and the water will be busy with boats, so I embrace the empty beach and dive into the translucent brine that’s all mine for a few magical moments.

© Jiri Foltynx | Shutterstock

another glorious bay

Sometimes you simply have to get wet. The Coast Track isn’t a technical trail, but the tidal range here is large, and there are several estuary crossings to negotiate. At Bark Bay and Torrent Bay, high-tide inland walk-around options exist, but Awaroa Inlet can only be crossed two hours either side of low tide. Campsites and huts have tide tables, and sometimes it’s necessary to set off before dawn to avoid delays, but even when you nail the timing, socks and shoes must be removed while you wade across.

The delightful distractions continue as the track tramps over the 853ft (260m) Tonga Saddle and drops to a sensational stretch of sand at Onetahuti Beach, before ambling past Arch Point – an extraordinary exhibition of rock art sculpted by the elements.

I enviously eye kayakers departing from the beach at Bark Bay, and make a mental note to return and paddle the park, for a new view of this epic coastline. Now, though, I have a bigger boat to catch, to the North Island. I wobble over the famous Falls River swingbridge to Torrent Bay, where another tidal crossing lies in wait en route to Anchorage and the trailhead at Marahau. PK

ORIENTATION

Start // Wainui Car Park

End // Marahau

Distance // 37 miles (60km)

Getting there // Marahau is easily accessed from Picton, where the Interislander ferry arrives from Wellington.

When to go // The Abel Tasman can be done any time of year, but the trails and campsites heave with hikers (and kayakers) during summer (Dec–Feb). October to November and March to April offer better conditions.

Where to stay // The Department of Conservation (DoC) operates huts and campsites along the route; book ahead.

What to take // A relatively gentle multiday hike, the Abel Tasman can easily be done in running shoes. The route rarely rears above 650ft (200m) and the weather is temperate, but take waterproofs and warm layers for evenings. Pack swimming gear, and a mask and snorkel.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

MULTI-SPORTS TRAILS

THE HEAPHY TRACK, NEW ZEALAND

Another Great Walk, the Heaphy Track can also be enjoyed in two distinct ways. As adventurers can explore the Abel Tasman by boot or boat, so the Heaphy can be hiked or biked (mountain bikes are permitted 1 May–30 November). You can tackle the track in both directions, either starting at Kohaihai and tracing the Tasman Sea along the South Island’s wild west coast, before crossing the Heaphy River, ascending Gouland Downs and traversing Kahurangi National Park via Perry Saddle, or beginning at Brown Hut and doing the same in reverse. Whichever way you approach it, the Heaphy is an epic challenge. Allow two nights/three days to pedal the route, or four days to walk it, and look out for powelliphanta (a giant carnivorous snail!) and roa (great spotted kiwi) en route.

Start // Kohaihai (near Karamea)

End // Brown Hut (Golden Bay, via Collingwood)

Distance // 49 miles (78.4km) one way

More info // www.doc.govt.nz/heaphytrack

© S-F | Shutterstock

crossing the bridge at the climax of New Zealand’s Heaphy Track

JATBULA TRAIL, AUSTRALIA

A hiking experience punctuated by plunge pools, the Jatbula Trail in the Northern Territory is an epic Australian adventure. Beginning with a boat trip across the Katherine River at 17 Mile Creek, the rugged route can be hiked independently or with guided groups, but the track is only marked in one direction, with blue triangles pointing the way from Katherine Gorge to Leliyn. It typically takes five days to trek the trail, which traverses Nitmiluk National Park, tracing an ancient indigenous songline and passing Jawoyn rock art and spectacular waterfalls tumbling from the towering Arnhem Land escarpment. Campsites at Biddlecombe Cascades, Crystal Creek, 17 Mile Falls, Sandy Camp and Sweetwater Pool are all situated beside swimming spots. This tropical trail is best walked during ‘the Dry’ (May–August). Some operators combine walks with gorge-exploring canoeing adventures.

Start // Nitmiluk Gorge

End // Leliyn (Edith Falls)

Distance // 38.5 miles (62km) one way

More info // www.northernterritory.com

CAUSEWAY COAST WAY, NORTHERN IRELAND

Stepping out along a super storied section of Ulster’s jagged shores, the Causeway Coast Way draws a dramatic line between the historic towns of Ballycastle and Portstewart, taking in a series of iconic sights along the way. These include the nerve-knackering Carrick-a-Rede Rope Bridge, medieval Dunluce Castle and, of course, the enigmatic Giant’s Causeway – a semi-submerged geological wonder comprised of 40,000 hexagonal basalt columns created either by a huge volcanic eruption, or a Celtic warrior called Fionn mac Cumhaill, depending on who you listen to. The walk can be done in either direction, over two or three relatively easy days, but if you want to up the ante, try running the route during the Causeway Coast ultramarathon, or paddle it while exploring the North Coast Sea Kayak Trail between Magilligan Point and the Glens of Antrim.

Start // Ballycastle

End // Portstewart

Distance // 32 miles (51km)

More info // www.causewaycoastway.com

© Tim Cuff | Alamy

Carrick-a-Rede on Northern Ireland’s Causeway Coast

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

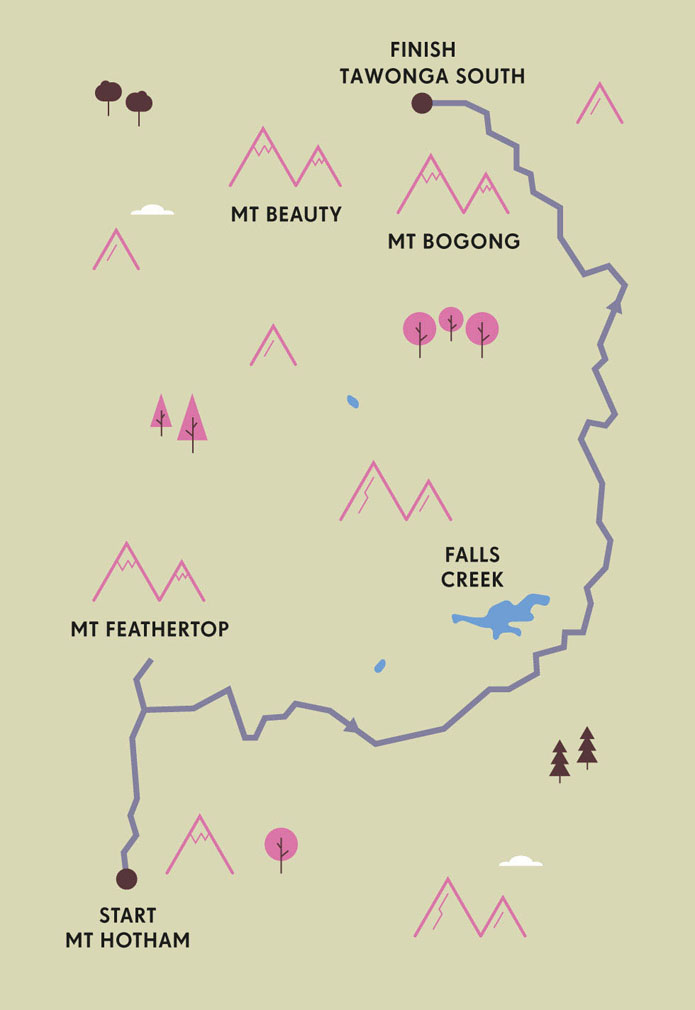

FEATHERTOP TO BOGONG TRAVERSE

Grab some altitude on this stunning multiday hike across the roof of Australia, crossing the state of Victoria’s fabled Bogong High Plains, home of the wild brumbies.

In the crisp, still dawn, golden sunbeams creep slowly across the High Plains, falling spindrift-like into my open tent. I take another sip of coffee. Nearby, a copse of gnarled snow gums turn molten orange, while somewhere above, a lonely currawong warbles the new morn. On Feathertop’s South Face, remnants of winter snow are burning bright crimson. The temperature is just above freezing.

© FiledIMAGE | Shutterstock

Mt Feathertop

Content in my sleeping bag, I review my plan to link Victoria’s three highest peaks in a leisurely five-day high-country amble. Yesterday afternoon, I’d left the car at 5577ft (1700m) on the Great Alpine Rd and walked north along the Razorback, a spectacular high ridge leading to Mt Feathertop, at 6306ft (1922m), Victoria’s second-highest peak. The views were incredible, but nothing surpassed dusk from the summit – a searing, snow gum-framed sun, sinking into scarlet oblivion beyond the ‘horns’ of distant Mt Buffalo.

Ahead was the Bogong High Plains, a high, desolate plateau sprinkled with historic huts and herds of brumbies (wild bush horses). Soon I’m packed and walking, but not before another quick summit dash to gaze on the aloof, table-topped Mt Bogong – aka Big Man, Victoria’s highest peak at 6516ft (1986m) and my final destination. I head for Diamantina Spur, a steep, relentless two-hour knee-breaking descent down to the Kiewa River, through scarred snow gums and blackened mountain ash. Bushfires are a regular occurrence in alpine Victoria, as entire ridges of grey skeletons testify.

© Gavin J Owen | Getty

a Bogong High Plains creek

Surviving Diamantina, I refill my water bottle from the clear Kiewa, before stopping for lunch at historic Blair Hut, idyllically located in a grassy, stream-side clearing. Echoes of long-gone mountain cattlemen and their horses resonate from the now-dilapidated structure, until I look up from my cheese and crackers to find I’m surrounded by horse-trekking tourists. I quickly seek solitude in the steep climb to Weston Hut.

© Ashley Whitworth | Alamy

Cape Hut

Flanking the High Plains, just inside the treeline, the original Weston Hut was constructed by cattlemen in the 1930s, and nearby, horse yards are still visible. It escaped the awful 2003 fires, but was reduced to cinders in 2006. Volunteers erected the present structure in 2011. The grassy surrounds make a pleasant campsite, and the hut offers refuge from the notorious High Plains weather.

The snow gums give way to tussock, brumby dung and alpine grasses as I ascend a snow-pole line on to the plateau. There’s a stark, desolate beauty about this barren high country that stretches for miles in all directions. I push on to a track junction, pole 333. A set of numbered snow poles spike in from the south like abandoned telegraph poles – from Mt Hotham, they cross the Cobungra Gap and count the way to Bogong. Another set disappear northwest over my left shoulder, on to the Fainters, but I focus on the string beckoning forwards. In the melancholy late- afternoon sun, all is still, empty, not another soul to be seen.

A few kilometres further I pause to observe a herd of brumbies eyeing me warily. The stallion stands his ground, snorting. I keep moving, eventually setting up camp beside a group of snow gums above Cope Saddle, as the temperature plummets with the sun.

© Age Fotostock | Alamy

the Kosciuszko Main Range is visible on the walk

“The last day’s trip is short but it’s the most magical. The sky is deep blue, the earth blindingly white and the air frigid”

Early the next day, I’m crunching through thin puddle-hiding-ice and the odd snowdrift. The pimply summit of Mt Cope (6027ft, 1837m) sits tantalisingly close to my right, but I’ve got a more pressing goal – the long-drop dunny at Cope Hut.

Mission accomplished, I rush through this ski area on the eastern edge of the plateau. Missing the moody High Plains solitude, I push on cross-country and bag Mt Nelse North, Victoria’s number three at 6181ft (1884m), and only marginally higher than the fire-trail beside it. Massive Bogong is looming ahead as I stroll downhill to Roper Hut.

The original Roper hut, dating from 1939, burnt in the 2003 fires, but arose phoenix-like in 2008 as an emergency shelter. I give myself the rest of the afternoon off, lounging in the sunshine and collecting water from a nearby cascade.

The following fog-shrouded morning is spent laboriously descending and ascending steep spurs covered in wet regrowth and fallen trees as I depart the High Plains, cross Big River and finally climb on to Bogong. From my welcome lunch spot on top of T-Spur, it’s only a short walk through lush snow meadows to the Cleve Cole Memorial Hut, although I take a detour via the picturesque Howman Falls.

© Bjorn Svensson | Alamy

here be wild brumbies

Nestled in a beautiful, sheltered bowl on the mountain’s southeastern flank, the hut commemorates a local skier caught in a blizzard. Made from stone, with bunks, indoor plumbing and solar panels, it’s one that’s popular with walkers, and I exchange pleasantries, though still opt to sleep in my cosy bomber tent – orientated, as always, to catch the sunrise.

Early morning sunlight sparkles off the surrounding snow and draws long shadows from the ubiquitous snow gums as I crunch above the tree line one last time. While this last day’s walk is short, it’s the most magical of the whole trip. The sky is deep blue, the earth blindingly white and the air frigid as I follow the pole line on to Bogong’s wide summit plateau.

The whole of the High Plains lie stretched out along my left, ending in the distinctive cap of Feathertop, while over to my right, a distant long white wall heralds the Kosciuszko Main Range, which is across the border in New South Wales. Clouds fill the valleys. I am absolutely alone, at altitude, and immensely happy. I take the mandatory selfie at Bogong’s summit cairn, then drop down the atmospheric, and at times decidedly airy Staircase, until the trees swallow me up and my thoughts stray to how I’m going to recover my car. SW

HIGH HORSES

In Australia, ‘brumby’ refers to any wild bush horse, and though herds are scattered across wilderness areas, they are commonly linked with the High Country, thanks to Australia’s favourite bard, AB ‘Banjo’ Patterson, who immortalised them in his poem The Man From Snowy River. Their presence in alpine areas is contentious and while scientists call for culls, many others call for their protection.

ORIENTATION

Start // Diamantina Hut, Mt Hotham

End // Mountain Creek, Tawonga South

Distance // 48 miles (77km)

Getting there // It’s a 4-hour-drive from Melbourne followed by the need for a car at both ends. Try taxis via www.mtbeauty.com or www.ptv.vic.gov.au.

When to go // September to May.

What to take // A good tent, sleeping bag, fuel stove, warm clothes, thermals and wet weather gear. Food for five days. Huts (except Cleve Cole) are for emergency use only.

Things to know // Shorter three-day circuits are possible: Mountain Creek, Eskdale Spur, Cleve Cole, Roper Hut, Timms Fire Trail, Bogong Ck Saddle, Quartz Ridge, Staircase, Mountain Ck; or Razorback, Feathertop, Diamantina, Weston Hut, Cobungra Gap, Dibbin Hut, Swindlers Spur, Razorback.

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

HIGH-COUNTRY WALKING

UPPER MUSTANG, NEPAL

Mysterious and sparsely populated, the magnificently remote Kingdom of Upper Mustang sits on a high, eroded plateau surrounded by snow-capped Himalayan peaks, nestled between Nepal’s Annapurna Range and the Tibetan border. The deep gorge of the Kali Gandaki cuts a dark swath through the dry, crumbling badlands and Tibetan culture reverberates across the scattered villages. With a mandatory guide and good fitness, you can make an adventurous 10-day return teahouse trek from Jomsom to Lo Manthang, the capital of Upper Mustang, following traditional footpaths, ancient trading routes, and the odd modern jeep track. Most of the trek sits between 9842ft (3000m) and 13,123ft (4000m) and the sheer scale of the scenery, not to mention the arcane monasteries, ancient frescoes, prayer-flagged passes and amazingly hospitable locals, will literally take your breath away.

Start/End // Jomsom

Distance / 85 miles (136km)

Duration // 10 days

More info // www.uppermustangnepal.com

© Sarawut Intarobx | Getty

Nepalese villagers cross a footbridge spanning dramatic Himalayan terrain

HOCHSCHWAB, AUSTRIA

In the north of Austria’s Styria lies the Hochschwab, a huge limestone plateau, where it’s possible to hike for days, staying at rustic (but civilised!) alpine hüttes. From Bodenbauer, climb up through pine-fringed alpine meadows to the sobering Das G’hackte, an almost vertical, chained ascent, before reaching the barren and rocky Hochschwab at 7470ft (2277m). Sink ein radler (beer and lemon soda) while you watch the sun set from the deck of the nearby Schiestlhaus and listen to the après-dinner singing. The high route heads west across Hundsboden (dog’s floor) past various tempting peaks like ZagelKogel (7398ft, 2255m, number two on the plateau) before dropping down to skirt the Sackwiesensee en route to Sonnschienhütte. Consider nailing omnipotent 6965ft (2123m) Ebenstein or meander over to tiny Androthalm for lunch, before heading back to the bright lights of Tragoss via Jassing and the Grüner See.

Start // Bodenbauer (St Ilgen)

End // Jassing (Tragoss)

Distance // 34km (without side trips)

Duration // Three or four days

More info // www.summitpost.org, www.osm.org

MT ARTHUR AND TABLELAND, New Zealand

Kahurangi National Park’s excellent network of backcountry huts provide many multiday tramping opportunities, and the Mt Arthur and Tableland area is spectacular. One challenging route climbs above Mt Arthur Hut (4298ft, 1310m) to the summit of Mt Arthur (5889ft, 1795m) then follows a high, exposed traverse to Salisbury Lodge (3707ft, 1130m). With good weather, the views are superb, in bad it’s abysmal and the alternate low-level route should be used. Continue on to the Tableland, a high limestone plateau covered in tussock, alpine flowers, snow and sinkholes. Pass Balloon Hut on the way to Lake Peel, a photogenic alpine tarn, before climbing the ridgetop for a sensational view of the Cobb Valley. Return to the car by the low-level route or drop down into the Cobb for further adventures.

Start/End // Flora Car Park, Motueka (alt Cobb Reservoir, Takaka)

Distance // 22 miles (35km)

Duration // Two to four days

More info // www.doc.govt.nz

- EPIC HIKES OF THE WORLD -

INDIANA JONES AND THE GOLD COAST

Encounter fascinating wildlife, waterfalls and ancient rainforest on this three-day walk through two national parks in southern Queensland.

Aglossy blue-black bird is assiduously arranging the scenery of its performance space. Blue petals and bottle tops are placed centre stage and anything that isn’t blue is briskly flicked aside. This remarkable scene, starring a satin bowerbird, is happening metres from where I’m staying at O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat in Lamington National Park, which is two hours’ drive inland from Brisbane in the volcanic and forested region of the Gold Coast hinterland.

© THPStock | Shutterstock

the forested Gold Coast hinterland of Queensland

The park, a Unesco World Heritage site, sits on a plateau almost a mile above the coast and contains a portion of the world’s largest stand of sub-tropical rainforest. More than 900 plant species, 200 bird species and 60 mammal species thrive up here, alongside 100 species of reptiles and amphibians. ‘Many specialised plants and animals only live here,’ says park ranger Kerri Brannon; ‘It’s all about the altitude.’ Lamington National Park is also the starting point for the 34-mile (54km) Gold Coast Hinterland Great Walk, which descends through dense rainforest, airy eucalyptus woodlands and even grasslands to Springbrook National Park on Queensland’s border with New South Wales.

© Robin Barton

deep in the woods of Lamington National Park

Lamington’s altitude has another effect: no matter how steamy it is on the Gold Coast, it will be 50% cooler in the mountains, which makes for comfortable walking conditions in Australia’s late summer. Pulling on my boots outside O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat at the trailhead (you can walk from east to west instead, but you’d be going uphill for most of the way), the sun had yet to warm the chilly mountain air. Filaments of mist filter through the vines and around the buttressed tree roots; if it seems primeval, that’s because it is. The forests date back hundreds of millions of years and were part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, before Australia broke apart from Antartica and South America, and ancient species such as cycads (which can be 500 years old), Antarctic beech and hoop pine were once dinosaur food.

On day one we follow the Border Track from the Green Mountains side of Lamington to Binna Burra, where another lodge has cabins and space for camping. This 13-mile (21km) section is the highest stage of the walk, with views to Mt Warning, the first place in Australia to get sunlight every morning.

My first wildlife encounter on leaving O’Reilly’s is with a gaggle of unperturbed brush-turkeys. But unless you have sharp eyes or the patience to stand silently, your encounters with birdlife tend to be audio rather than visual. This makes the birds easier to identify. Does it sound like the crack of a whip? That’s a whipbird. Does it sound like a mewling cat? That’s a catbird. A rifleshot? That’s a Paradise riflebird. You get the idea. And if you hear a car alarm or mobile phone, that’ll be an Albert’s lyrebird, an elusive but accomplished mimic.

an eastern whipbird

“If you hear a car alarm or mobile phone, that’ll be an Albert’s lyrebird, an elusive but accomplished mimic”

At the junction of the Border Track with the Coomera Falls circuit I take the Coomera turning, where I meet Rusty and Nev, two park rangers attending to one of the regular rainy season landslips. ‘Some parts of the trail date back to the Depression labour of the 1930s and the 1940s, when unemployed men, and war veterans who found it hard to adapt to civilian life, went into the woods to adjust to life,’ explains Rusty. ‘They’d fill backpacks with rocks from the creek and carry them along the trails. It was hard, dangerous work – there were no safety harnesses in those days.’ Snakes were a hazard too, and it’s a little later that I encounter Australia’s third-most venomous reptile, a young male tiger snake warming himself on the trail.

The natural history lesson continues on the second section of the walk, which connects Lamington National Park with its eastern relative Springbrook. An intense fragrance in the air turns out to be patch of lemon-scented teatrees. A lattice of roots around a tree trunk is a strangler fig, imperceptibly killing its host over decades. And then my second Indiana Jones moment occurs: strung across the path, one after another, are spider webs 10ft (3m) wide at head height, each patrolled by a golden orb spider the breadth of my hand.

© Michael Hoeck | Shutterstock

a strangler fig grips its victim