|  |

In which James Squire gets invited to a wedding

***

On June 13, 1793, convicts Matthew Gibbons and Margaret Gordon got hitched. Not much is known about the bride, but the groom came over on the Second Fleet (on the Surprize, the ship that brought Squire brewing rival John Boston to town. We’ll hear more about him in the next chapter). Gibbons was done for stealing one-and-a-quarter pounds of tea and got seven years in Sydney for his trouble.

In Sydney Cove he ran a pub (which was more like a room with a few containers of beer than anything we might call a pub today) named The Dragoon in George Street. In the same year he was married, Gibbons joined the NSW Corps. According to Michael Flynn’s book The Second Fleet, he headed back to England with the disgraced corps when they left. He and Margaret had two children in England before heading back to Sydney for 13 years, then went back to the Mother Country and then back to Sydney again, where he would ultimately kark it as an old man.

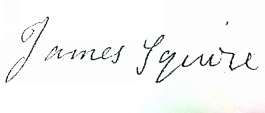

But what is relevant to us is that James Squire was a witness to that couple’s special day. And it’s special for us because he signed his name on the marriage certificate. Near as I can find, that’s the only thing we have written in his own hand (though I’m pretty sure he did initialise his own will). Which makes it pretty important if you’re a massive James Squire geek.

What’s also worthwhile about the signature is that he was able to write it at all. This means he was literate – he could spell and write his own name, which shows he had some level of education. Some on the First Fleet couldn’t write and would initial any documents with an X. The bride Margaret Gordon was one of them – instead of a signature, she scrawled an X next to where someone else has written her name.

Secondly, it’s worth noting that, in his signature, James Squire drops the S at the end of his name. From before the time of the First Fleet through to his death notice in the Sydney Gazette, his name is consistently written as Squires. And yet when the man writes his own name, he spells it without the S. Weird. Even weirder is his gravestone drops the S too. Did the government spell his name wrong for most of his life and he was too polite to correct them? Or did Squire have some quiet sort of objection to the S at the end of his name and chose to remove it himself?

One other curious thing about his signature is that it does not resemble the one that features on the modern-day beer brand that bears his name.

Here’s the genuine James Squire signature from the marriage certificate

––––––––

And here’s the one the beer brand uses

They don’t look that similar, do they? Particularly the surname. Sure, you could suggest the beer brand signature has been embellished to make it look a bit more like a logo and maybe you could be right (though it should be pointed out that the beer brand doesn’t claim the logo is his actual signature).

But here’s what I’m thinking. I’m thinking someone based it on the signature of the wrong James Squire. See, our man Squire had a son with Elizabeth Mason, who was also called James. He was an executor of his dad’s estate and signed several documents relating to the probate.

And here’s the signature of Squire Jr

You ask me, the way the surname is written looks very similar to the signature on that appears on the beer labels – look at the way the way the Q joins up at the bottom of the U and the fact that the dot for the letter I actually appears over the R. To me it looks like the signature on the beer bottles isn’t actually that of Squire’s but rather has been based on his son’s.

Incidentally, while we know what the real Squire signature looks like, we don’t know what the man himself looked like. How tall was he? What colour was his hair? Or his eyes? Was he fat or thin? Did he have a beard? We really don’t know. I could find no written description that offers even the slightest bit of information about his physical appearance – though given he appears to have had little trouble finding female companionship we can assume he hadn’t been clobbered with the ugly stick. But beyond that, we know bugger all.

Squire doesn’t even seem to have bothered to pay someone to paint his portrait either. Squire became a successful businessman who owned a stack of land, so he would have definitely had the money to pay a convict artist. Similarly, by the early 1800s, he was enough of a local identity in the Kissing Point area that it would seem some artist would deem him worthy of a sitting. And yet there is no artistic likeness of him that we know of.

One researcher has engaged in a bit of wishful thinking in suggesting there is in fact a painted likeness of Squire. They point to a painting of Squire’s Kissing Point property created by convict artist Joseph Lycett. Technically speaking, the painting is of the Parramatta River, as that takes up almost a third of the canvas, and shows Squire’s estate way off in the distance.

On the river is a small sailboat with four people on board. It’s claimed that one of those four people is Squire. The basis of this claim seems to be nothing more than the fact Squire’s will mentions a boat he owned called the Lucy (which he would leave to his housekeeper and lover Lucy Harding) There is no evidence to suggest that boat in the foreground – or any of the other four boats that can be seen – is Squire’s.

Also, if you look closely at the painting you can see that none of the people in the boat have any facial features. Their heads are just empty circles wearing hats, which makes them useless for gaining any idea of what Squire looked like. Even if is Squire, which it probably isn’t.

The painting is dated 1825, which is three years after James Squire died. Its title is The Property of the Late Mr James Squires (there’s that S at the end of his name again). The date and the painting’s title strongly suggest the painting was created after Squire’s death. So, unless Squire was a colonial zombie, it seems highly unlikely he’s anywhere in this painting.